STUDY

EPRS | European Parliamentary Research Service

Author: Anna Zygierewicz

Ex-Post Impact Assessment Unit

PE 581.414 - July 2016

The Erasmus+

Programme

(Regulation EU

No. 1288/2013)

European Implementation

Assessment

PE 581.414 1

The Erasmus+ Programme

(Regulation EU No. 1288/2013)

European Implementation Assessment

In October 2015, the Committee on Culture and Education (CULT) of the European

Parliament requested to undertake an implementation report on the Erasmus+

Programme (Regulation EU No. 1288/2013). Dr Milan Zver (EPP, Slovenia) was

appointed rapporteur.

Implementation reports by EP committees are routinely accompanied by European

Implementation Assessments, drawn up by the Ex-Post Impact Assessment Unit of the

Directorate for Impact Assessment and European Added Value, within the European

Parliament's Directorate-General for Parliamentary Research Services.

Abstract

This European Implementation Assessment has been provided to accompany the work

of the European Parliament’s Committee on Culture and Education in scrutinising

the implementation of the Erasmus+ programme.

The Erasmus+ programme for Union action in the field of education, training, youth

and sport was launched on 1 January 2014 and will run until 31 December 2020.

It brings together seven successful programmes which operated separately between

2007 and 2013 (the Lifelong Learning Programme, five international cooperation

programmes and the Youth in Action programme), and also adds the area of sports

activities.

The opening analysis of this Assessment, prepared in-house by the Ex-Post Impact

Assessment Unit within EPRS, situates the programme within the context of education

policy, explains its legal framework and provides key information on its

implementation. The presentation is followed by opinions and recommendations

of selected stakeholders. A separate chapter is dedicated to the sport, which is the new

element of the Erasmus+ programme.

Input to the EIA was also received from two independent groups of experts

representing the Technical University of Dresden and the University of Bergen, and

the Turku University of Applied Sciences.

- The first research paper presents implementation of Key Action 1 (KA1) – Learning

mobility of individuals in the field of education, training and youth.

- The second research paper presents implementation of Key Action 2 (KA2)

– Cooperation for innovation and the exchange of good practices in the field

of education, training and youth.

The two research papers, containing key findings and recommendations, are included

in full as annexes to the in-house opening analysis.

Implementation of the Erasmus+ Programme (Regulation EU No 1288/2013)

PE 581.414 2

AUTHORS

- Opening analysis written by Dr. Anna Zygierewicz, Ex-Post Impact Assessment

Unit

- Research paper analysing the implementation of the Erasmus+ programme –

Learning mobility of individuals in the field of education, training and youth

(Key Action 1), written by Prof. Dr. Thomas Köhler from the Technical

University of Dresden and Prof. Dr. Daniel Apollon from the University

of Bergen

- Research paper analysing the implementation of the Erasmus+ programme –

Cooperation for innovation and the exchange of good practices in the field

of education, training and youth (Key Action 2), written by Dr. Juha Kettunen

from the Turku University of Applied Sciences

ABOUT THE PUBLISHER

This paper has been drawn up by the Ex-Post Impact Assessment Unit of the Directorate

for Impact Assessment and European Added Value, within the Directorate–General for

Parliamentary Research Services of the Secretariat of the European Parliament.

To contact the Unit, please email EPRS-ExPostImpact[email protected]uropa.eu

LINGUISTIC VERSIONS

Original: EN

This document is available on the internet at: http://www.europarl.europa.eu/thinktank

DISCLAIMER

The content of this document is the sole responsibility of the author and any opinions

expressed therein do not represent the official position of the European Parliament. It is

addressed to the members and staff of the EP for their parliamentary work. Reproduction

and translation for non-commercial purposes are authorised, provided the source

is acknowledged and the European Parliament is given prior notice and sent a copy.

Manuscript completed in July 2016. Brussels © European Union, 2016.

PE: 581.414

ISBN 978-92-823-9477-9

DOI: 10.2861/981220

QA-04-16-518-EN-N

European Implementation Assessment

PE 581.414 3

Contents

Abbreviations.................................................................................................................................... 4

Introduction...................................................................................................................................... 5

Chapter 1. The place of the Erasmus+ programme in EU education policy ..................................... 5

Chapter 2. Main rules of the programme.......................................................................................... 8

I – Structure of the programme.................................................................................................... 8

II – Budget of the programme .................................................................................................... 12

III – Basic rules concerning the implementation of the programme..................................... 13

Chapter 3. Implementation of the programme ................................................................................ 17

I – Overall implementation of the programme........................................................................ 17

II – Adult education..................................................................................................................... 23

III – International dimension of higher education .................................................................. 25

IV – Multilingualism.................................................................................................................... 29

V – Conclusions............................................................................................................................ 32

Chapter 4. Sport.............................................................................................................................. 34

I – Background to sport activities in the EU............................................................................. 34

II – Selected documents of the European Parliament ............................................................. 38

III – Sport in the Erasmus+ programme ................................................................................... 39

IV – Implementation of Sport activities .................................................................................... 42

V – Conclusions............................................................................................................................ 47

Selected references........................................................................................................................... 48

Annexes:

Annex I: The implementation of the Erasmus+ programme – Learning mobility

of individuals in the field of education, training and youth (Key Action 1)

Research paper by Prof. Dr. Thomas Köhler from the Technical University of Dresden

and Prof. Dr. Daniel Apollon from the University of Bergen

Annex II: The implementation of the Erasmus+ programme – Cooperation for innovation

and the exchange of good practices in the field of education, training and youth

(Key Action 2)

Research paper by Dr Juha Kettunen from Turku University of Applied Sciences

Implementation of the Erasmus+ Programme (Regulation EU No 1288/2013)

PE 581.414 4

Abbreviations

DCI

Development Cooperation Instrument

DG

European Commission, Directorate General

DG EAC

European Commission, Directorate General Education and Culture

CULT

European Parliament, Committee on Culture and Education

EACEA

Education, Audiovisual and Culture Executive Agency

EAEA

European Association for the Education of Adults

ECAS

European Commission Authentication Service

EDF

European Development Fund

ELL

European Language Label

EMJD

Erasmus Mundus Joint Doctorates

EMJMD

Erasmus Mundus Joint Master Degrees

EMMC

Erasmus Mundus Master Course

EMPL

European Parliament, Committee on Employment and Social Affairs

ENI

European Neighbourhood Instrument

EPALE

Electronic Platform for Adult Education

ET 2020

EU cooperation in education and training

EU

European Union

EUCIS-LLL

European Civil Society Platform on Lifelong Learning

EUROSTAT

Statistical office of the European Union

FYROM

Former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia

ICM

International Credit Mobility

ICT

Information and communication technology

INI

Own-Initiative Report

IPA2

Instrument for Pre-accession Assistance

KA1

Key Action 1

KA2

Key Action 2

KA3

Key Action 3

LLP

Lifelong Learning Programme

MFF

Multiannual Financial Framework

MS

Member State

NA

National Agency

NGO

Non-governmental organisation

OJ

Official Journey of the European Union

OLS

On-line Linguistic Support

OMC

Open Method of Cooperation

PI

Partnership Instrument

RSP

European Parliament resolution

STEM

Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics

UNESCO

United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization

VET

Vocational Education and Training

European Implementation Assessment

PE 581.414 5

Introduction

Methodology of the Introduction

This introduction is based on an analysis of the Erasmus+ programme documents,

including the regulation establishing the programme and the rules concerning

the implementation, and the analysis of the implementation data and reports.

The opinions and recommendations of selected stakeholders on the implementation

of the Erasmus+ programme were also analysed.

The EPRS peer-reviewed the opening analysis. In addition, the European Commission

was requested to comment on the opening analysis.

The author would like to thank the different contributors for all the comments

and recommendations.

Chapter 1. The place of the Erasmus+ programme in EU

education policy

The importance of education is recognised within the European Union. The reference

to education can be found in the Preamble to the Treaty on the Functioning of the

European Union (TFEU), where it is stated that Member States are ’determined

to promote the development of the highest possible level of knowledge for their peoples

through a wide access to education and through its continuous updating’.

Article 6 TFEU provides that the EU has competence to carry out actions to support,

coordinate or supplement the actions of the Member States in certain specified areas, one

of which concerns education, vocational training, youth and sport.

The basis of the Erasmus+ programme for the period 2014-2020 is Regulation (EU)

No. 1288/2013 establishing the programme

1

.

Article 4 of the Regulation defines the objectives of the programme as being to contribute

to the achievement of:

1) the objectives of the Europe 2020 strategy

2

, which are focused on:

- resolving the problem of early school leavers by reducing the dropout rate;

1

Regulation (EU) No 1288/2013 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 11 December

2013 establishing ‘Erasmus+’: the Union programme for education, training, youth and sport and

repealing Decisions No 1719/2006/EC, No 1720/2006/EC and No 1298/2008/EC, OJ L 347/50

of 20.12.2013.

2

Communication from the Commission: Europe 2020. A strategy for smart, sustainable and

inclusive growth, COM(2010) 2020 and Europa 2020 webpage.

Implementation of the Erasmus+ Programme (Regulation EU No 1288/2013)

PE 581.414 6

- increasing the share of the population aged 30-34 having completed tertiary

education.

2) the objectives of the strategic framework for European cooperation in education and

training ('ET 2020'), including the corresponding benchmarks:

a) strategic objectives:

- Making lifelong learning and mobility a reality with education and vocational

training being more responsive to change and to the wider world;

- Improving the quality and efficiency of education and training, by raising the levels

of basic skills such as literacy and numeracy, making mathematics, science

and technology more attractive and strengthening linguistic abilities;

- Promoting equity, social cohesion and active citizenship so that all citizens can

continue to develop job-specific skills throughout their lifetime;

- Enhancing creativity and innovation, including entrepreneurship, at all levels

of education and training; in particular, individuals should be helped to become

digitally competent and to develop initiative, entrepreneurship and cultural

awareness;

b) benchmarks

3

:

- at least 95% of children (from 4 to compulsory school age) should participate

in early childhood education;

- fewer than 15% of 15-year-olds should be under-skilled in reading,

mathematics and science;

- the rate of early leavers from education and training aged 18-24 should be

below 10%;

- at least 40% of people aged 30-34 should have completed some form of higher

education;

- at least 15% of adults should participate in lifelong learning;

- at least 20% of higher education graduates and 6% of 18-34 year-olds with

an initial vocational qualification should have spent some time studying

or training abroad;

- the share of employed graduates (aged 20-34 with at least upper secondary

education attainment and having left education 1-3 years ago) should be

at least 82%.

3) the sustainable development of partner countries in the field of higher education;

4) the overall objectives of the renewed framework for European cooperation in the

youth field (2010-2018): a) to create more and equal opportunities for all young people in

education and in the labour market and b) to promote the active citizenship, social inclusion

and solidarity of all young people;

3

The 2015 Joint Report of the Council and the Commission on the implementation of the strategic

framework for European cooperation in education and training (ET 2020) (OJ C 417 of 15.12.2015)

showed that serious challenges remain.

European Implementation Assessment

PE 581.414 7

5) the objective of developing the European dimension in sport, in particular grassroots

sport, in line with the Union work plan for sport

4

; and

6) the promotion of European values in accordance with Article 2 of the Treaty on the

European Union (TEU), which are:

respect for human dignity, freedom, democracy, equality, the rule of law and respect for

human rights, including the rights of persons belonging to minorities. These values are

common to the Member States in a society in which pluralism, non-discrimination,

tolerance, justice, solidarity and equality between women and men prevail.

4

Given the new competences of the EU in the area of sport, the role of Erasmus+ in this area will be

broadly presented in chapter 4.

Implementation of the Erasmus+ Programme (Regulation EU No 1288/2013)

PE 581.414 8

Chapter 2. Main rules of the programme

I – Structure of the programme

The Erasmus+ programme for the period from 1 January 2014 to 31 December 2020

brought together seven programmes which were operating separately between 2007 and

2013, namely:

- the Lifelong Learning Programme

5

: Erasmus for higher education, Leonardo da Vinci

for vocational education and training, Comenius for school education, Grundtvig

for adult learning, Jean Monnet for promoting European integration;

- five international cooperation programmes: Erasmus Mundus

6

, Tempus, Alfa,

Edulink, bilateral cooperation programmes in the field of higher education (with

Canada, the United States, Australia, Japan, New Zealand and South Korea);

- the Youth in Action

7

programme.

It also added sport as a new element (which had already been introduced in

a preparatory phase since 2009). In addition, the Erasmus+ programme continues

supporting the Jean Monnet activities.

Figure 1. Erasmus+ programme 2014-2020 and its predecessors

Source: European Commission: Slide 3 and Slide 8

5

Decision No 1720/2006/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 15 November 2006

establishing an action programme in the field of lifelong learning, OJ L 327, 24.11.2006, p. 45–68

and Decision No 1357/2008/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 16 December

2008 amending Decision No 1720/2006/EC establishing an action programme in the field

of lifelong learning, OJ L 350, 30.12.2008.

6

Decision No 1298/2008/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 16 December 2008

establishing the Erasmus Mundus 2009-2013 action programme for the enhancement of quality

in higher education and the promotion of intercultural understanding through cooperation with

third countries, OJ L 340, 19.12.2008.

7

Decision No 1719/2006/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 15 November 2006

establishing the Youth in Action programme for the period 2007 to 2013, OJ L 327, 24.11.2006.

European Implementation Assessment

PE 581.414 9

Based on the combination of best experiences from the previous programmes, Article 1

of the Regulation establishing Erasmus+, determines that the programme covers

the following fields:

a) education and training at all levels, in a lifelong learning perspective, including

school education (Comenius), higher education (Erasmus), international higher

education (Erasmus Mundus), vocational education and training (Leonardo

da Vinci) and adult learning (Grundtvig);

b) youth (Youth in Action), particularly in the context of non- formal and informal

learning;

c) sport, in particular grassroots sport.

Jean Monnet activities also form part of the Erasmus+ programme (see below).

In the field of education and training (Article 6), the Erasmus+ programme shall pursue

its objectives through the following types of actions:

a) learning mobility of individuals;

b) cooperation for innovation and the exchange of good practices;

c) support for policy reform.

Ad a) Learning mobility of individuals (Article 7) may support:

- the mobility of students in all cycles of higher education and of students, apprentices

and pupils in vocational education and training, which may take the form

of studying at a partner institution or traineeships or gaining experience as an

apprentice, assistant or trainee abroad. Degree mobility at Master's level may be

supported through the Student Loan Guarantee Facility

8

;

- the mobility of staff, within the programme countries

9

, which may take the form

of teaching or assistantships or participation in professional development

activities abroad;

- the international mobility of students and staff to and from Partner Countries

10

as regards higher education, including mobility organised on the basis of joint,

double or multiple degrees of high quality or joint calls.

Ad b) Cooperation for innovation and the exchange of good practices (Article 8) may

support:

- strategic partnerships between organisations and/or institutions involved in

education and training or other relevant sectors aimed at developing and

implementing joint initiatives and promoting peer learning and exchanges of

experience;

- partnerships between the world of work and education and training institutions

in the form of:

knowledge alliances between, in particular, higher education institutions and

the world of work aimed at promoting creativity, innovation, work-based

8

Referred to in Article 20.

9

Referred to in Article 24(1): EU Member States plus Former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia,

Ireland, Liechtenstein, Norway and Turkey.

10

The list of the programme countries is available at the Erasmus+ programme website.

Implementation of the Erasmus+ Programme (Regulation EU No 1288/2013)

PE 581.414 10

learning and entrepreneurship by offering relevant learning opportunities,

including developing new curricula and pedagogical approaches;

sector skills alliances between education and training providers and the world

of work aimed at promoting employability, contributing to the creation

of new sector-specific or cross-sectoral curricula, developing innovative

methods of vocational teaching and training and putting the Union

transparency and recognition tools into practice;

- IT support platforms, covering all education and training sectors, including in

particular eTwinning, allowing peer learning, virtual mobility and exchanges of

good practices and opening access for participants from neighborhood countries;

- development, capacity-building, regional integration, knowledge exchanges and

modernisation processes through international partnerships between higher

education institutions in the EU and in partner countries, in particular for peer

learning and joint education projects, as well as through the promotion

of regional cooperation and National Information Offices, in particular with

neighbourhood countries.

Ad c) Support for policy reform (Article 9) shall include the activities initiated at EU level

relating to:

- the implementation of the EU policy agenda on education and training in the

context of the OMC

11

, as well as to the Bologna and Copenhagen processes;

- the implementation in Programme countries of EU transparency and recognition

tools

12

, and the provision of support to Union-wide networks and European non-

governmental organisations (NGOs) active in the field of education and training;

- the policy dialogue with relevant European stakeholders in the field of education

and training;

- NARIC, the Eurydice and Euroguidance networks, and the National Europass

Centres;

- policy dialogue with partner countries and international organisations.

Jean Monnet activities (Article 10) are aimed to:

- promote teaching and research on European integration worldwide among

specialist academics, learners and citizens, in particular through the creation

of Jean Monnet Chairs and other academic activities, as well as by providing aid

for other knowledge-building activities at higher education institutions;

11

Article 2: Open Method of Coordination (OMC) means an intergovernmental method providing

a framework for cooperation between the Member States, whose national policies can thus be directed

towards certain common objectives; within the scope of the Programme, the OMC applies to education,

training and youth.

12

In particular the single EU framework for the transparency of qualifications and competences

(Europass), the European Qualifications Framework (EQF), the European Credit Transfer and

Accumulation System (ECTS), the European Credit System for Vocational Education and

Training (ECVET), the European Quality Assurance Reference Framework for Vocational

Education and Training (EQAVET), the European Quality Assurance Register for Higher

Education (EQAR) and the European Association for Quality Assurance in Higher Education

(ENQA).

European Implementation Assessment

PE 581.414 11

- support the activities of academic institutions or associations active in the field

of European integration studies and support a Jean Monnet label for excellence;

- support six European institutions

13

pursuing an aim of European interest;

- promote policy debate and exchanges between the academic world and policy-

makers on Union policy priorities.

In the field of youth (Article 12) the programme pursues its objectives through

the following types of actions:

a) learning mobility of individuals;

b) cooperation for innovation and the exchange of good practices;

c) support for policy reform.

Ad a) Learning mobility of individuals (Article 13) supports:

- the mobility of young people in non-formal and informal learning activities between the

Programme countries; such mobility may take the form of youth exchanges and

volunteering through the European Voluntary Service, as well as innovative

activities building on existing provisions for mobility;

- the mobility of persons active in youth work or youth organisations and youth leaders;

such mobility may take the form of training and networking activities;

- the mobility of young people, persons active in youth work or youth

organisations and youth leaders, to and from partner countries, in particular

neighbourhood countries.

Ad b) Cooperation for innovation and the exchange of good practices (Article 14)

supports:

- strategic partnerships aimed at developing and implementing joint initiatives,

including youth initiatives and citizenship projects that promote active

citizenship, social innovation, participation in democratic life and

entrepreneurship, through peer learning and exchanges of experience;

- IT support platforms allowing peer learning, knowledge-based youth work,

virtual mobility and exchanges of good practice;

- development, capacity-building and knowledge exchanges through partnerships

between organisations in Programme countries and partner countries,

in particular through peer learning.

Ad c) Support for policy reform (Article 15) includes activities relating to:

- the implementation of the Union policy agenda on youth through the OMC;

- implementation in the Programme countries of Union transparency and

recognition tools, in particular the Youthpass, and support for Union-wide

networks and European youth NGOs;

- policy dialogue with relevant European stakeholders and structured dialogue

with young people;

13

The European University Institute of Florence; the College of Europe (Bruges and Natolin

campuses); the European Institute of Public Administration (EIPA), Maastricht; the Academy of

European Law, Trier; the European Agency for Development in Special Needs Education,

Odense; the International Centre for European Training (CIFE), Nice.

Implementation of the Erasmus+ Programme (Regulation EU No 1288/2013)

PE 581.414 12

- the European Youth Forum, resource centres for the development of youth work

and the Eurodesk network;

- policy dialogue with partner countries and international organisations.

The Commission monitors the implementation of the EU youth policy based

on established indicators.

The sport activities within the Erasmus+ programme are presented in chapter 4 of this

introduction.

II – Budget of the programme

The overall budget for the new Erasmus+ programme totals EUR 14.7 billion (Heading

1). Additionally, to strengthen the international dimension of the programme, EUR 1.68

billion was added under Heading 4. The latter part of the programme budget comes from

the Development Cooperation Instrument (DCI), the European Neighbourhood

Instrument (ENI), the Instrument for Pre-accession Assistance (IPA2), the Partnership

Instrument (PI) and the European Development Fund (EDF).

Figure 2. The Erasmus+ budget division

Source: Erasmus+ programme website in the UK.

According to Article 18.2 of the Regulation, out of the 8.8% dedicated to ’Other‘

(as in Figure 2):

- 3.5% will be spent on the Student Loan Guarantee Facility;

- 3.4% on operating grants to national agencies, and

- 1.9 % to cover administrative expenditure.

European Implementation Assessment

PE 581.414 13

The budget of the programme represents an increase of about 40% compared to the

amount allocated to the education, learning and youth programmes for the years 2007-

2013. At the same time, however, this represents a decrease in comparison to the initial

proposal of the European Commission, in which the budget was planned to amount

to EUR 17.29 billion under Heading 1 and EUR 1.81 billion under Heading 4

14

.

The annual programme budget foreseen for 2016 for the EU Member States, countries

belonging to the European Economic Area (EUR31), other countries participating in the

programme (Former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia, Turkey and Western Balkans

countries) together with internal assigned revenues, amounts to EUR 2.229 billion, and

will come from following appropriations

15

:

— from the budget of the Union (EUR28) under Heading 1: EUR 1.69 billion;

— from the budget of the Union (EUR28) under Heading 4: EUR 247.17million;

— arising from the participation of the EFTA/EEA countries: EUR 53.67 million;

— from the European Development Fund (EDF) (EUR28): EUR 15 million;

— from external assigned revenues arising from the participation of other countries

in the programme (Former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia, Turkey and

Western Balkans): EUR 141.58 million;

— corresponding to internal assigned revenues from recoveries: EUR 73.72 million.

III – Basic rules concerning the implementation of the programme

1. Programme Guide and annual work programmes

The Commission prepared the Erasmus+ Programme Guide

16

for potential applicants,

meaning those who wish to be participating organisation or participants in the

programme. The guide describes the rules and conditions for receiving a grant from the

programme and has three main parts:

— Part A presenting the general overview of the programme, its objectives,

priorities and main features, the programme countries, the implementing

structures and the overall budget available;

— Part B provides specific information about the actions of the programme covered

by the guide;

— Part C gives detailed information on procedures for grant application and

selection of projects, as well as the financial and administrative provisions linked

to the award of an Erasmus+ grant.

14

Proposal for a regulation of the European Parliament and of the Council establishing ‘ERASMUS

FOR ALL’, The Union Programme for Education, Training, Youth and Sport, COM(2011) 788

final.

15

Amendment of the 2016 annual work programme for the implementation of 'Erasmus+': the

Union Programme for Education, Training, Youth and Sport’ C(2016)1122 of 26 February 2016.

16

Erasmus+ Programme Guide. Version 2 (2016): 7 January 2016 and Addendum to the Erasmus+

Programme Guide. Version 1 of 25 April 2016 prepared following the re-opening, in Greece, of the

Erasmus+ actions in the field of youth.

Implementation of the Erasmus+ Programme (Regulation EU No 1288/2013)

PE 581.414 14

The Programme Guide forms an integral part of calls of proposal.

The financial arrangements under the Erasmus+ programme have been simplified

in comparison to previous editions, inter alia, through the use of lump sums, the

reimbursement on the basis of unit costs and the flat-rate financing. The rules

of application were described by the Commission in a separate document

17

.

The Erasmus+ programme is implemented also on the basis of the annual work

programmes adopted by the European Commission. As stated in Article 35 of the

regulation establishing the Erasmus+ programme, each annual work programme shall

ensure that the general objectives (Article 4) and specific objectives (Articles 5 –

on education and training, Article 11 - on youth and Article 16 - on sport) are

implemented annually in a consistent manner and shall outline the expected results,

the method of implementation and its total amount.

2. Implementation bodies, decentralised and centralised actions

Article 27 of the regulation establishing Erasmus+ programme identifies the

implementing bodies:

— the Commission at EU level;

— the national agencies at national level in the programme countries.

The programme countries established one (in most of the countries) or more (e.g. two

in Ireland and Italy, three in Belgium and Germany) national agencies. The list of the

agencies is available at the European Commission website.

In 27 partner countries (outside the EU), the national Erasmus+ offices are responsible

for the management of the international dimension of the higher education aspects of the

programme. The list of the offices is available at the EACEA website.

The actions of the Erasmus + programme are divided into:

— decentralised actions, which are managed in each programme country by one

or more national agencies appointed by their national authorities;

— centralised actions, which are managed at the European level by the Directorate

General for Education and Culture (DG EAC) of the European Commission and

by the Education, Audiovisual and Culture Executive Agency (EACEA) located

in Brussels.

The budget of the programme is divided amongst the actions, with approximately:

— 82% spent through decentralised actions;

— 18% spent through centralised actions

18

.

17

The use of lump sums, the reimbursement on the basis of unit costs and flat-rate financing under

the ’Erasmus+’ Programme, C(2013)8550 of 4 December 2013.

18

2014 annual work programme for the implementation of "Erasmus+", the Union Programme

for Education, Training, Youth and Sport, C(2013)8193 of 27 November 2013.

European Implementation Assessment

PE 581.414 15

3. Selection of best proposals

A crucial role in the choice of the proposals to be financed within the Erasmus+

programme is played by independent experts specialising in the field of education,

training, youth and sport who peer-review proposals.

To ensure that the same standards concerning the peer review of proposals are applied

in all national agencies, the European Commission prepared a Guide for Experts on Quality

Assessment

19

, which provides information on:

- the role and appointment of experts;

- the principles of the assessment;

- the assessment process in practice;

- information on how to assess the award criteria for each action and field.

General rules concerning the evaluation of proposals at the national level, as described

in the guide for experts, are:

- the assessment and selection of grant applications is organised on the basis

of a peer review;

- based on the experts' assessment, a list of grant applications per action and per

field ranked in quality order is established, which serves as a basis for the

national agency to take the grant award decision, following the proposal of the

Evaluation Committee;

- experts are appointed on the basis of their skills and knowledge in the areas and

the specific field(s) of education, training and youth in which they are asked

to assess applications. Experts must not have a conflict of interest in relation

to the proposals. To ensure their independence, the names of the experts are not

made public;

- an application can receive a maximum of 100 points for all criteria relevant for

the action (see table 1); in order to be considered for funding, an application has

to score at least 60 points in total and score at least half of the maximum points

for each award criterion.

The EACEA and national agencies organise their own pools of experts. The recruitment

of experts to evaluate project in the EACEA was opened in September 2013

20

and

corrected a year later. The call is open until the end of September 2020. Candidates must

register under the European Commission Authentication Service (ECAS). National

agencies open calls for experts nationally or internationally. The calls can be opened for

short or long term. National agencies usually ask candidates for experts to register

in their on-line databases or to send offers within the procurement procedures.

19

2016 ERASMUS+. Guide for Experts on Quality Assessment. Actions managed by National

Agencies.

20

Call for expressions of interest EACEA/2013/01 for the establishment of a list of experts to assist the

Education, Audiovisual and Culture Executive Agency in the framework of the management of European

Union programmes in the field of education, audiovisual, culture, youth, sport, EU aid volunteers, and

citizenship or any other programmes delegated to the Agency, and Corrigendum.

Implementation of the Erasmus+ Programme (Regulation EU No 1288/2013)

PE 581.414 16

There were claims, e.g. from national agencies and organisations acting in the area

of education and training, that Member State evaluation criteria for proposals are not

sufficiently harmonised and should be improved.

There were also claims that most of the deadlines for applications fall at the same time.

Some experts specialise in more than one field of education, training and youth, and

therefore assess proposals in more than one Erasmus+ action. As a result, they suffer

from periodical work overload, which may impact on the quality of the assessments.

Additionally, some stakeholders claim that there should be more the one deadline per

year (e.g. in adult education), which could also help to solve the problem.

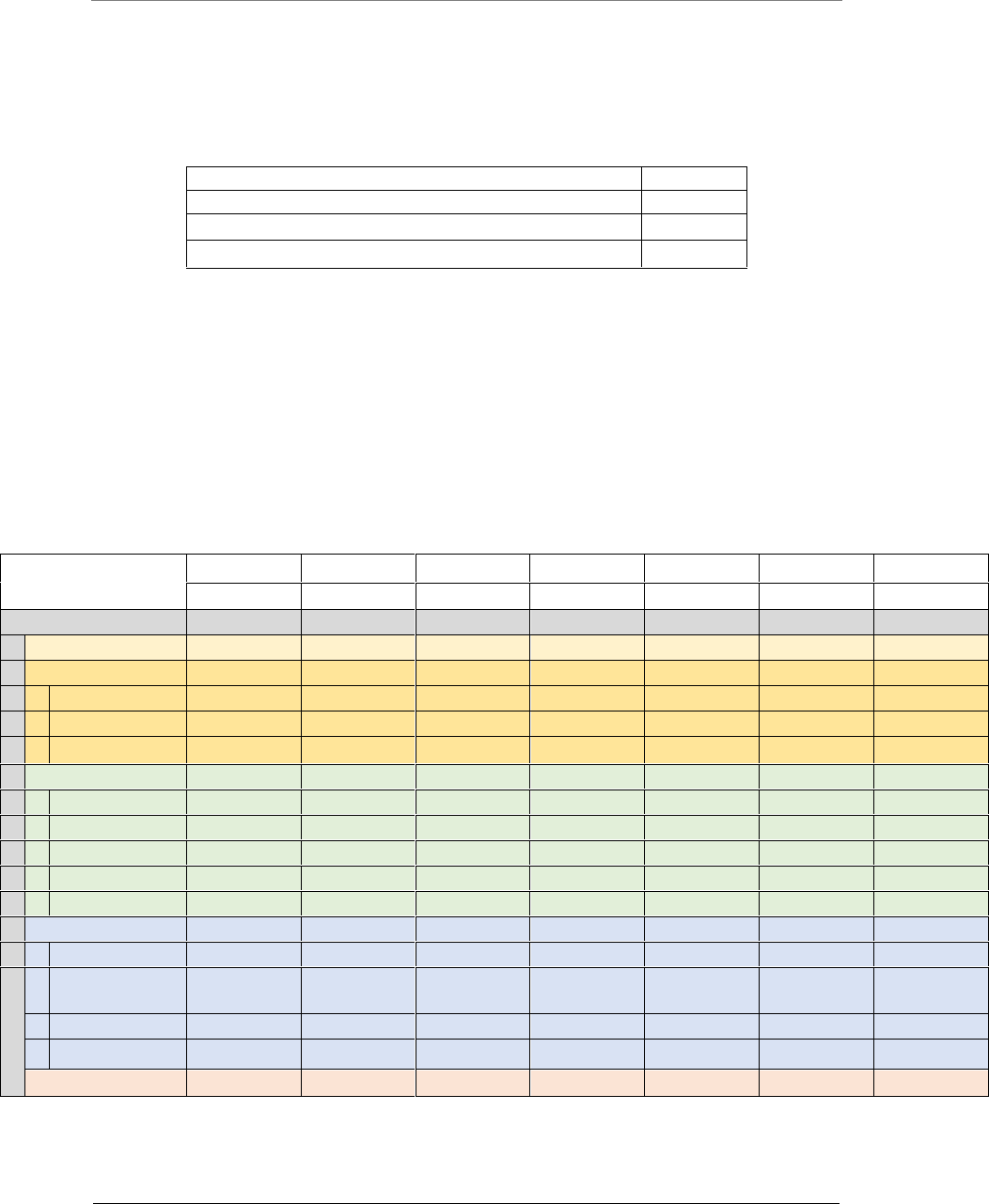

Table 1. Award criteria for projects evaluated at the national level

Award criteria

Maximum scores of award criteria per action

Key Action 1

Key Action 2

Key Action 3

Accreditation

of higher

education

mobility

consortia

Mobility

projects

in the field

of Higher

Education

between

Programme

and Partner

Countries

Mobility

projects

in the fields

of school

education,

vocational

education

and training,

adult

education

and youth

Strategic

partnerships

in the field

of Education,

Training and

Youth

Structured

Dialogue:

meetings

between

young people

and decision

makers in the

field of youth

Relevance

of the project

1

30

30

30

30

30

Quality of the

project design and

implementation

2

20

30

40

20

40

Quality of the

project team and

the cooperation

arrangements

3

20

20

:

20

:

Impact and

dissemination

30

20

30

30

30

TOTAL

100

100

100

100

100

Source: 2016 ERASMUS+. Guide for Experts, op.cit

1) Corresponding criterion for higher education mobility consortia: "relevance of the consortium"

2) Corresponding criterion for higher education mobility consortia: "quality of the consortium activity design

and implementation"

3) Corresponding criterion for higher education mobility consortia: "quality of the consortium composition

and the cooperation arrangements"

European Implementation Assessment

PE 581.414 17

Chapter 3. Implementation of the programme

Key findings

The Commission data on the implementation of the Erasmus+ programme

are available only for 2014; the data for 2015 will be published later in 2016.

However, part of the raw data for the implementation of the centralised actions

for 2015 is available at the EACEA website.

The success rate of applications in most of the Erasmus+ actions is relatively

low, which can be related to insufficient budget compared to the high demand,

and/or to the quality level of the proposals. The Commission data does

not provide clear evidence concerning the quality of accepted proposals.

The success rate in Key Action 1 was generally higher that in Key Action 2.

In 2014, within Key Action 1 the biggest part of the budget (58%) was spent

on projects in higher education, while within Key Action 2 the biggest part

(36%) was spent on projects in school education.

I – Overall implementation of the programme

The European Commission published data on the implementation of the Erasmus+

Programme in 2014 in the Erasmus+ Programme Annual Report 2014 and the Erasmus Impact

Study Regional Analysis. Both reports were published in January 2016. The data for 2015

is planned to be published in autumn 2016.

According to the report, in 2014, inter alia:

– over EUR 2 billion were distributed to support actions in education and training

(69% of the budget), youth (10%) and sport (1%), as well as the other actions

covered by the programme;

– above 650 000 individual mobility grants were offered for people to study, train,

work or volunteer abroad (400 000 higher education and vocational students'

exchanges, 100 000 volunteers and young people undertaking youth work

abroad, 150 000 teachers, youth trainers and other staff who gained mobility

grants for their professional development);

– 11 new Joint Master Degrees were set up with non-EU countries within the first

year of Erasmus+, to be added to some 180 Joint Master Degrees and Joint

Doctorates available previously under Erasmus Mundus;

– over 1 700 cooperation projects across the education, training and youth sectors,

addressing key challenges such as early school leaving, the need to equip young

generations with digital skills, and promoting tolerance and intercultural

dialogue were funded;

– around 50 not-for-profit sports events, collaborations between sports bodies and

grass-roots organisations, as well as the first EU Sport Forum, were funded;

Implementation of the Erasmus+ Programme (Regulation EU No 1288/2013)

PE 581.414 18

– 212 projects were funded supporting the improvement of the excellence

of European Studies programmes within the Jean Monnet Actions .

Table 2. Projects granted in Key Action 1 and Key Action 2 in 2014

KA1 and KA2

Projects

Grant

(million EUR)

Participants

Organisations

KA1 - Mobility

15 951

1 191

647 694

57 825

KA2 - Cooperation

1 732

346

172 681

9 823

Total:

17 683

1 537

820 375

67 648

Source: Erasmus+ Programme. Annual Report 2014.

Table 3. Projects granted in Key Action 1 in 2014 in detail

KA1 - Mobility

Projects

Grant

(million

EUR)

Organisations

Participants

Granted

Success

rate

School education

staff mobility

2 806

31%

43.01

4 252

21 037

VET learner and

staff mobility

3 156

53%

264.12

18 094

126 004

Higher education

student and staff

mobility

3 620

71%

600.82

3 620

341 393

Adult education

staff mobility

424

18%

9.92

961

5 593

Youth mobility

5 749

49%

125.70

29 851

151 395

Large-Scale

Volunteering Events

5

50%

0.35

5

196

Erasmus+ Joint

Master Degrees

11

18%

21.24

46

437

Erasmus Mundus

Joint Doctorates

42

100%

32.51

246

257

Erasmus Mundus

Master Degrees

138

100%

48.76

750

1 379

Other actions (OLS, …)

:

:

44.19

:

:

Total:

15 951

:

1 190.61

57 825

647 691

Source: Erasmus+ Programme. Annual Report 2014.

According to the Commission’s report for 2014, in Key Action 1, the grants were

distributed between the education and training sectors and youth in the following

proportions:

— Higher education

58%

— Vocational education and training

25%

— Youth

12%

— School education

4%

— Adult education

1%

European Implementation Assessment

PE 581.414 19

Table 4. Projects granted in Key Action 2 in 2014 in detail

KA2 - Cooperation

Projects

Grant

(million EUR)

Organisa-

tions

Participants

Granted

Success

rate

Partnerships for

School Education

206

19.49%

46 127 908

1 265

13 563

Strategic Partnerships

for Schools only

522

17.41%

78 272 387

2 566

93 351

Strategic Partnerships

for Adult Education

215

16.32%

45 764 442

1 289

8 238

Strategic Partnerships

for Higher Education

154

16.79%

42 016 082

1 046

17 130

Strategic Partnerships

for Vocational

Education and Training

377

22.75%

96 034 874

2 492

9 575

Strategic Partnerships

for Youth

258

14.91%

30 033, 152

1 165

16 948

Transnational

Cooperation Activities

for Youth

:

:

6 938 693

:

12 957

Transnational

Cooperation Activities

for other Sectors

:

:

774 281

:

919

Total:

1,732

17.90%

345 961 819

9 823

172 681

Source: Erasmus+ Programme. Annual Report 2014.

According to the statistical annex to the Commission’s report for 2014, in Key Action 2,

total amount of grant were distributed between the education and training sectors and

youth in the following proportions:

— School education

36%

— Vocational education and training

28%

— Adult education

13%

— Higher education

12%

— Youth

11%

Table 5. Projects granted in Key Action 3 in 2014

KA3 - Policy

Projects

Grant

(million EUR)

Average

per project

(EUR)

Organisations

Granted

Success

rate

Education & Training

7

35%

11 261 310

1 608 759

:

Youth

1

50%

1 934 009

1 934 009

:

Total:

8

36%

13 195 319

1 649 415

127

Source: Erasmus+ Programme. Annual Report 2014.

General findings of the Commission’s report for 2014:

— KA1 – Learning Mobility of Individuals:

66% of the total budget was granted to the KA1 projects;

Implementation of the Erasmus+ Programme (Regulation EU No 1288/2013)

PE 581.414 20

about 500 000 young people studied, trained, volunteered or participated

in youth exchanges abroad;

150 000 staff members of educational institutions and youth

organisations got the opportunity to improve their competencies

by teaching and training abroad;

some 180 Erasmus Mundus Masters Degrees/ Joint Doctorates, initially

funded under the LLP programme were financed under KA1, as well as

11 new Erasmus Mundus Joint Masters Degrees;

On-line Linguistic Support (OLS) allowed 126 000 participants to assess

their knowledge of the language in which they will work or study;

45% followed an OLS language course afterwards.

— KA2 – Cooperation for Innovation and the Exchange of Good Practices:

over 1 700 projects, involving around 10 000 organisations and 160 000

participants in learning, teaching and training activities, and 13 000 more

in transnational cooperation activities, received support (from the total

amount of EUR 345.96 million) for enhancing the labour market

relevance of education and training systems and for tackling the skills

gaps Europe is facing. 65% of the projects produce intellectual outputs

while in learning, teaching and training (LTTs), preference is given

to short term learning, training and teaching activities;

high demand from high quality applications in all fields, combined with

the limited budget, resulted in a rather low success rate (18%);

79 capacity building cooperation projects with youth organisations

in partner countries were financed, aiming at helping the modernisation

and internationalisation of their youth systems;

10 knowledge alliances projects, which bring businesses and higher

education institutions together to develop new ways of creating,

producing and sharing knowledge, were selected amongst high

competition (4% success rate) and granted EUR 8.4 million;

— KA3 – Support to Policy Reform:

8 European policy experimentations projects were granted EUR 13.2

million with the aim to test innovative measures through rigorous

evaluation methods;

cooperation with international organisations was pursued in particular

with the OECD on country analysis and with the Council of Europe

in the field of human rights/citizenship education, youth participation,

citizenship and social inclusion and dialogue between Roma

communities and mainstream society;

IT platforms such as eTwinning, the Electronic Platform for Adult

Learning (EPALE) or the European Youth Portal, and the VALOR project

dissemination platform, were further developed and used to facilitate the

communication within and about the programme and to promote the

dissemination of its results.

European Implementation Assessment

PE 581.414 21

— Jean Monnet Activities:

212 projects, aiming at promoting excellence in teaching and research

in the field of EU studies worldwide, were financed with a total grant

of EUR 11.3 million;

65% of the applications concerned teaching and research with a vast

majority concerning Chairs and Modules, while 25% were projects

aiming at creating and applying new methodologies or spreading

knowledge about the European integration process among a wider target

audience;

7 institutions pursuing an aim of European interest received an operating

grant for a total amount of EUR 3.8 million.

The regional analyses of the projects funded under the previous Erasmus programme

show that:

— overall, at least 90% of Erasmus students in all regions participated in the

Erasmus programme in order to experience living abroad, meet new people,

learn or improve a foreign language and develop their soft skills; 87% did so in

order to enhance employability abroad, which for 77% is more important than

employability at home;

— former Erasmus students are half as likely to experience long-term

unemployment than those who did not go abroad; and students in eastern

Europe even reduced their risk of long-term unemployment by 83% by taking

part in Erasmus;

— similarly, traineeships and work placements had a positive impact on finding

a job – this was particularly valuable for students from countries in southern

Europe, such as Italy and Portugal, where half of those training abroad were

offered a position by their host company;

— overall, Erasmus students were not only more likely to be employed, but also

more likely to secure management positions; on average 64% of Erasmus

students, compared to 55% of their non-mobile peers, held such positions within

5-10 years from graduation; this was even more true for Erasmus students from

central and eastern Europe, where around 70% of them end up in managerial

positions; but

— lack of financial support prevented 53% of students in southern Europe and 51%

in eastern Europe from taking part in Erasmus. Financial barriers are even higher

for students from a non-academic family background: 57% in southern Europe

and 54% in Eastern Europe of students from a non-academic family background

do not participate in mobility for this reason. This is why additional financial

support was provided to students from a disadvantaged background since the

start of Erasmus+ in 2014.

One of the most striking finding of the analysis is the low success rate in most of the

Erasmus+ programme actions. The low success rate can potentially lower the level

of interest of applicants in future. The preparation of proposal is time-consuming and

also often costly, which may be especially difficult for smaller applicants. The

Commission suggests increasing the budget of the programme to allow financing a larger

number of proposals. This would appear to be a reasonable recommendation, given that

Implementation of the Erasmus+ Programme (Regulation EU No 1288/2013)

PE 581.414 22

the studies show that the impact of the projects on education, training and youth is

significant, and especially important for organisations and project participants with less

experience in international cooperation and in applying for grants supporting mobility.

Nevertheless, more profound analysis of the reasons lying behind the low success rate is

needed. The Commission report does not present information on the number of grant

applications assessed by external experts above and below the thresholds, or on how

many points a proposal had to receive to be financed in different actions and in different

countries. This information would allow for a better diagnose of the reasons for the low

success rates, and would enable steps to be taken to raise the level of applications,

if necessary, and to better distribute funds in the Erasmus+ budget, both current and

additional, if such are approved by the European Parliament.

The perception of the Erasmus+ programme among stakeholders is generally very

positive, but there are still claims concerning, especially, the need for more simplification

and harmonisation. As an example, the opinion of the European Civil Society Platform on

Lifelong Learning (EUCIS-LLL) on the Erasmus+ programme is presented with selected

comments and recommendations which are as follow:

a. Positive:

i. the Erasmus+ programme as a whole;

ii. the increased budget of the programme;

iii. the flat rate system and lump sums;

iv. the trans-sectoral dimension of the programme.

b. Negative:

i. the programme guide is generally perceived as being complicated, and some

national agencies started to prepare simplified versions;

ii. better harmonisation between national agencies is needed – there is a need for

common implementation guidelines;

iii. the increased bureaucracy (e.g. for adult education and for smaller projects);

iv. the filling-in of the e-form tool is time-consuming;

v. the lack of clear definitions (e.g. intellectual output);

vi. the trans-sectoral dimension of the programme is positive, but in practice

it does not work well, e.g. it is not possible any more within the Key Action 2;

vii. the lump sums are appreciated, but they are considered as too small;

viii. the overall project coordination is not covered by the administrative lump

sum;

ix. travel costs do not fully reflect the geographical realities;

x. due to the decentralisation, Brussels-based European civil social organisations

apply for funding through one of the Belgian National Agencies which made

the situation more difficult for them and for other Belgian applicants.

Concerning the last claim, the Commission explained that additional funding was

transferred to the Belgian agencies facing this problem; it should nevertheless

be monitored if the Belgian organisations can successfully compete for grants with

European organisations.

European Implementation Assessment

PE 581.414 23

II – Adult education

Adult education actions (previously implemented within the Grundtvig programme)

should address the challenges of the renewed European Agenda for Adult Learning

(EAAL) included in the Council's resolution of 28 November 2011. The aim of the

Agenda, which is referred to in recital 18 of the regulation establishing the Erasmus+

programme, is to enable all adults to develop and enhance their skills and competences

throughout their lives.

Based on the Programme Guide

21

, within:

1) Staff mobility the support is offered to:

- teaching or training assignments, which allow staff of adult education organisations

to teach or to provide training at a partner organisation abroad;

- staff training, which allows the professional development of adult education staff

in the form of: a) participation in structured courses or training events abroad;

b) a job shadowing/observation period abroad in any relevant organisation active in

the adult education field.

2) Strategic partnerships the support is offered to

22

:

- activities that strengthen the cooperation and networking between organisations;

- testing and/or implementation of innovative practices in the field of education,

training and youth;

- activities that facilitate the recognition and validation of knowledge, skills and

competences acquired through formal, non-formal and informal learning;

- activities of cooperation between regional authorities to promote the development

of education, training and youth systems and their integration in actions of local

and regional development;

- activities to support learners with disabilities/special needs to complete education

cycles and facilitate their transition into the labour market, including by combating

segregation and discrimination in education for marginalised communities;

- activities to better prepare and deploy the education and training of professionals for

equity, diversity and inclusion challenges in the learning environment;

- activities to promote the integration of refugees, asylum seekers and newly arrived

migrants and raise awareness about the refugee crisis in Europe;

- transnational initiatives fostering entrepreneurial mind-sets and skills, to encourage

active citizenship and entrepreneurship (including social entrepreneurship), jointly

carried out by two or more groups of young people from different countries.

According to the European Commission’s report on the implementation of Erasmus+

programme in 2014 and the statistical annex to the report, within:

21

Erasmus+ Programme Guide. Version 2 (2016) and Addendum, op.cit.

22

Presented Strategic Partnerships are not restricted to adult education but are equally applicable

in e.g. VET or HE.

Implementation of the Erasmus+ Programme (Regulation EU No 1288/2013)

PE 581.414 24

– Adult education staff mobility (Key Action 1):

the interest remains high;

the average success rate in 2014 was at the level of 18.5%, but it varied

between national agencies from 86% in Norway, 75% in the German-

speaking part of Belgium, 67% in Lichtenstein and 63% in Austria, to 2%

in Turkey and 3% in Bulgaria;

424 projects were granted (out of 2 296 submitted), with 5 593 adult

education staff participations, and with an average funding of EUR 1 773

per participant;

94% of participants were planning to undertake staff training abroad

(participation in a structured course or job shadowing), while the other

6% planned to deliver teaching or training at partner organisations

abroad;

5 countries register more than half of all adult education staff

participants: Germany, Poland, Turkey, France and Italy.

– Strategic partnerships in the field of adult education (Key Action 2):

the interest remains high;

the average success rate in 2014 was at the level of 16 3%;

215 projects were granted (out of 1 317 submitted), with 1 289

organisations and 8 391 participants involved and with an average

number of 6 partners per project;

53% of partnerships are focused on short term learning, teaching

or training activities and 94% of partnerships projects aimed to produce

intellectual outputs.

The Electronic Platform for Adult Learning in Europe (EPALE) was created for teachers,

trainers and volunteers, as well as policy-makers, researchers and academics involved in

adult learning, to facilitate the cooperation and the promotion of activities as well as the

exchange of good practice. The available materials are organised according to five main

themes: Learner Support, Learning Environments, Life Skills, Policy and Quality. EPALE

is implemented by a Central Support Service and in 2014-2015 a network of 30 National

Support Services in Erasmus+ Programme countries. In 2016 there were 35 EPALE

National Support Services applications founded within the Erasmus+ programme.

The European Association for the Education of Adults (EAEA) prepared

recommendations and a feedback document for the improvement of the Erasmus+

programme. The main suggestions of the EAEA are as follows:

- to allow larger-scale projects to be implemented at the EU level (via EACEA),

as well as to allow bigger and European organisations to apply for funding at the

EU level and not at the national level;

- to standardise the NAs’ information, selection and administrative procedures;

- to improve the participation of the partner countries in the programme and

especially from the European Neighbourhood countries;

- to promote the programme in countries where level of participation is relatively

low;

European Implementation Assessment

PE 581.414 25

- Staff mobility:

to allow umbrella organisations to apply for funding on behalf of their

member organisations and then administer the individual mobilities;

to reintroduce the database of approved training;

to introduce two (or three) application deadlines instead of one.

- Strategic partnerships:

to simplify the application procedure (which, while being universal

for the whole programme, in the area of adult education is more

complicated now that it was before);

to reintroduce the preparatory visits, which allowed organisations

to know each other and to better prepare their applications;

to increase the budget for adult education within the Erasmus+

programme, as the budget decline and the new procedure for allocating

funds for projects and the new formula for distributing funding across

Member States, led to a significant fall in the number of transnational

cooperation projects;

to standarise the definition of ’intellectual output’.

The analysis of the adult education activities within Key Action 1 can be also found

in Annex I.

III – International dimension of higher education

1. General rules

The international dimension is one of the biggest new elements of the Erasmus+. It brings

together, under the supervision of the European Commission’s DG Education and

Culture, several separate programmes (inter alia, Tempus, Alfa, Edulink, Erasmus

Mundus,) which were overseen in the previous financing period by other DGs, mainly

DG Development.

The recent UNESCO Science Report showed that there has been a growth in the number

of tertiary-level education students worldwide, rising from 1.1 million in 1985, to 1.7

million in 1995, 2.8 million in 2005 and 4.1 million in 2013.

According to the regulation establishing the Erasmus+ programme, 'international' relates

to any action involving at least one programme country and at least one third country

(partner country). Within the international dimension of Erasmus+ in the field of higher

education, according to the Programme Guide, support is offered to:

— Key Action 1:

International credit mobility of individuals and

Erasmus Mundus Joint Master Degrees

promoting the mobility of learners and staff from and to Partner Countries;

— Key Action 2: Capacity-building projects in higher education promoting cooperation

and partnerships that have an impact on the modernisation and internationalisation

Implementation of the Erasmus+ Programme (Regulation EU No 1288/2013)

PE 581.414 26

of higher education institutions and systems in Partner Countries, with a special focus

on Partner Countries neighbouring the EU;

— Key Action 3: Support to policy dialogue through the network of Higher Education

Reform Experts in Partner Countries neighbouring the EU, the international alumni

association, policy dialogue with Partner Countries and international attractiveness

and promotion events;

— Jean Monnet activities with the aim of stimulating teaching, research and reflection

in the field of European Union studies worldwide.

In addition, other Actions of the Programme (Strategic Partnerships, Knowledge Alliances,

Sectors Skills Alliances, and Collaborative Partnerships) are also open to organisations from

Partner Countries in so far as their participation brings an added value to the project.

The presentation of the international dimension of the programme can be also found

in Annex I. The examples of strategic partnership cooperation projects are described

in Annex II.

New rules to attract non-EU students, researchers and trainees to the EU were approved

by Parliament in May 2016, with the aim to make it easier and more attractive for people

from third countries to study or do research at EU universities. Based on them, inter alia:

- students and researchers are allowed to stay in the Member State for at least

9 months after completing their studies/research to look for work or set up

a business;

- students have the right to work at least 15 hours a week;

- researchers have the right to bring their family members with them and these

family members are entitled to work during their stay in Europe;

- students and researchers may move more easily within the EU during their stay;

in future, they will not need to file a new visa application, but only to notify the

Member State to which they are moving; researchers will also be able to move for

longer periods than those currently allowed.

2. Funded projects

According to the Commission’s Erasmus+ Programme. Annual Report 2014:

1) Erasmus Mundus Joint Master Degrees (EMJMDs): within the call published

in December 2013, 11 projects were selected, which involve the participation of 46

higher education institutions from 18 different Programme Countries and 437

participants. Success rate was at the level of 18%. Total grants awarded

amounted to EUR 21.2 million.

In 2014 there were still 42 ongoing Erasmus Mundus Joint Doctorates (EMJDs)

involving 246 organisations and still recruiting students or PhD candidates.

A total amount of EUR 32.5 million was allocated to cover the ongoing EMJDs.

Doctoral fellowships were awarded to:

European Implementation Assessment

PE 581.414 27

80 PhD candidates from programme countries (including 11 fellowships

awarded through the Former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia and

Turkey ‘window’) and

177 candidates from partner countries (including 5 fellowships awarded

through a western Balkans ‘window’).

There were no new calls for EMJDs, as doctoral degrees have been part of the

Horizon 2020 programme since 2014.

2) Erasmus Mundus Master Courses (EMMCs): in 2014 there were 138 ongoing

EMMC involving 750 organisations. A total amount of EUR 48.8 million was

allocated to cover the ongoing EMMCs. Erasmus Mundus scholarships were

awarded to:

452 programme country Master students (including 114 scholarships

awarded through a geographic ‘window’, 17 for nationals of the FYROM

or Turkey) and

927 partner country Master students (including 89 scholarships awarded

through a Western Balkans ‘window’ and 45 scholarships awarded

through a Syria ‘window’).

3) Jean Monnet Activities: within the total number of 219 projects awarded a grant,

most were from Member States, but there were also 10 projects from Ukraine,

6 from Turkey, 4 from Belarus and Moldova, 2 from Serbia and 1 from Albania.

From other regions there were 5 projects from China, 4 from the United States,

3 from New Zealand, 2 from Chile and 7 from seven other partner countries.

According to the EACEA data, in 2015 there was a rise in the number of projects

from partner countries receiving grants:

Jean Monnet Modules, Chairs and Centres of Excellence – for 181 granted

projects, 93 came from partner countries and among them: 34 from

Russia, 16 from the United States, 9 from Taiwan, 6 from Ukraine and

5 from Turkey;

Jean Monnet Support to Institutions and Associations – of 14 projects

awarded grants, 7 came from partner countries;

Jean Monnet Networks and Jean Monnet Projects – of 66 projects awarded

grants, 27 came from partner countries.

4) Credit mobility: according to the Commission data:

the total budget for 2014-2020 amounts to EUR 761.3 million (coming

from different funding for different world regions);

the budget for 2015 amounted to EUR 121 million (of which EUR 68.8

million for neighbourhood countries and the Western Balkans) was

almost entirely spent after two rounds of calls with only EUR 11 million

remaining (out of which more than EUR 4 million in the United

Kingdom);

in 2015 among the total number of mobilities funded were: 1) 10 673

learners and 6 697 staff members incoming to the EU and 2) 3 242

learners and 4 505 staff members outgoing from the EU. The biggest

number of participants was from Russia, with more than 3 000, Ukraine

Implementation of the Erasmus+ Programme (Regulation EU No 1288/2013)

PE 581.414 28

and Serbia, with more than 2 000, and China and Israel, with almost 1 500

for each country.

3. Impact of the Erasmus Mundus Master courses on participants

The Erasmus Mundus provides support with the aim to promote European higher

education, to help improve and enhance the career prospects of students and to promote

intercultural understanding through cooperation with third countries (in accordance with

EU external policy objectives in order to contribute to the sustainable development

of third countries in the field of higher education) (Article 3 of the Regulation).

The implementation of the programme is undertaken by means of the following actions:

1) Erasmus Mundus joint programmes (masters and doctoral programmes)

of outstanding academic quality, including a scholarship scheme;

2) Erasmus Mundus partnerships between European and third-country higher

education institutions as a basis for structured cooperation, exchange

and mobility at all levels of higher education, including a scholarship scheme;

3) Promotion of European higher education through measures enhancing

the attractiveness of Europe as an educational destination and a centre

of excellence at world level.

Mobility of successful students coming from programme and partner countries

23

is financed under Heading 1. Successful students from other countries - partner countries

- are financed under Heading 4

24

.

The last Graduate Impact Survey which involved almost 1 500 graduates (71%)

and students (29%) of the Erasmus Mundus Master Courses, showed that around:

- 90% of the participants were satisfied with the programme, with more than 65%

extremely and very satisfied. Only 2.5% were clearly not satisfied;

- 81% of participants were satisfied with the quality of the courses offered at the

host universities. Some fields were rated as particularly satisfactory, such

as Health and Welfare (4.19 points out of 5 on the satisfaction scale), while others,

such as the Humanities and Arts, as well as Social Sciences, Business and Law,

were slightly less satisfactory (3.99 and 3.96 points respectively);

- 73% of graduates identified ’contacts to potential employers‘ as being the aspect

most lacking in the programme, with ’practical experience‘ being the second

(55%),’integration activities in the host countries’ (38.5%) as third, and

’mentoring‘ as fourth (36%);

- 59% of participants found their first job while studying or within 2 months after

graduation and an additional 26% between the third and sixth month after

graduation; only 15% looked for a job for longer than six months;

23

The Erasmus+ programme countries are the member states of the EU plus non-EU programme

countries: Former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia (FYROM), Iceland, Liechtenstein, Norway

and Turkey.

24

Guidance note: Terminology used in Erasmus Mundus scholarship statistics.

European Implementation Assessment

PE 581.414 29

- 59% of participants said that the field of their study matched best with their field

of work;

- 93% of graduates believe that their language skills increased due to Erasmus

Mundus, 67% of whom felt this increase to be very high or rather high.

Participants declared that the programme had the highest impact on their:

- intercultural competencies – 58.7%

- career – 43.5%

- subject related expertise – 33.7%

- personality – 26.3%

- attitude towards Europe and the EU – 20.1%

- private life – 9.9%

The Graduate Impact Survey also showed that the Erasmus Mundus programme is still not

very well known in the programme and partner countries, even if it proved to be

an efficient tool for improving labour market related skills as well as the linguistic skills

and intercultural competencies of participants.

IV – Multilingualism

The significance of multilingualism for the professional and private life of Europeans

is well-known and confirmed in several analyses and studies.

The language skills are a form of human capital as: 1) they are productive on the labour

market through enhancing earning and employment; 2) they require costs – real costs

as well as time and effort; and 3) they are embodied in the person

25

.

The latest study (2016) on foreign language proficiency and employability prepared for

the Commission showed that there is clear evidence that foreign language skills are a career

driver – if they form part of a broader package of relevant (specific) skills. In combination with the

right educational background and relevant work experience, foreign language skills provide access

to jobs in international trade and services for which they are a prerequisite.

The study also showed that one third of employers experience difficulties in filling positions as a

result of a lack of applicants’ foreign language skills. Two thirds of these difficulties are due to

insufficient foreign language levels of job applicants, one third is due to the inability of finding

suitable candidates with proficiency in a particular language.

As for the importance of different languages, the study showed that English is by far the

most important language in international trade and the provision of services. Over four in five

employers interviewed and three quarters of advertised online vacancies stating that this was the

most useful language for the jobs discussed/reviewed in all sectors and in almost all non-English

speaking countries. For a fifth to a quarter of employers a language other than English is the most

25