Jessica Bolter

Emma Israel

Sarah Pierce

Four Years of Profound Change

Immigration Policy during the Trump Presidency

U.S. IMMIGRATION POLICY PROGRAM

Jessica Bolter

Emma Israel

Sarah Pierce

Migration Policy Institute

February 2022

Four Years of Profound Change

Immigration Policy during the Trump Presidency

Contents

1 Introduction ......................................................................................................................................................................................1

A. What Has Changed?....................................................................................................................................................................2

B. Driving Reform through Layered Changes ...................................................................................................................5

C. Pushback and the Search for Alternatives .....................................................................................................................7

D. Cataloging a Period of Intense Change ..........................................................................................................................8

2 Pandemic Response ...............................................................................................................................................................9

A. Travel Bans and Visa Processing ........................................................................................................................................ 10

B. Border Security and Asylum Processing at the U.S.-Mexico Border ........................................................... 16

C. Interior Enforcement ...............................................................................................................................................................20

D. The Immigration Court System ......................................................................................................................................... 24

E. Immigration Benets ............................................................................................................................................................... 26

3 Immigration Enforcement .......................................................................................................................................... 30

A. Border Security ............................................................................................................................................................................ 31

B. Interior Enforcement ............................................................................................................................................................... 42

4 U.S. Department of Justice ........................................................................................................................................56

A. Instructions to Immigration Judges ............................................................................................................................... 65

B. Attorney General Referral and Review ......................................................................................................................... 69

5 Humanitarian Migration ...............................................................................................................................................73

A. Refugees .......................................................................................................................................................................................... 74

B. Asylum Seekers ........................................................................................................................................................................... 79

C. Unaccompanied Children .................................................................................................................................................... 89

D. Temporary Protected Status Recipients ...................................................................................................................... 96

E. Victims of Tracking and Other Crimes ...................................................................................................................... 99

6 U.S. Department of State ..........................................................................................................................................100

7 U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services and U.S. Department of

Labor

......................................................................................................................................................................................................110

A. Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals ......................................................................................................................122

B. Immigrant Visas .........................................................................................................................................................................124

C. Nonimmigrant Visas ..............................................................................................................................................................129

D. Parole ...............................................................................................................................................................................................138

8 Other Actions ............................................................................................................................................................................. 140

9 Conclusion .....................................................................................................................................................................................144

About the Authors ......................................................................................................................................................................... 146

Acknowledgments ........................................................................................................................................................................ 147

MIGRATION POLICY INSTITUTE | 8 MIGRATION POLICY INSTITUTE | 1

FOUR YEARS OF PROFOUND CHANGE: IMMIGRATION POLICY DURING THE TRUMP PRESIDENCY FOUR YEARS OF PROFOUND CHANGE: IMMIGRATION POLICY DURING THE TRUMP PRESIDENCY

1 Introduction

The Trump administration set an unprecedented pace for executive action on immigration.

1

In four

years, it completed 472 executive actions aecting U.S. immigration policy, with 39 more proposed but

unimplemented when the administration ended. Some of these changes were sweeping—undoing the

priorities of the entire interior enforcement apparatus, for example—while others were smaller, more

technical adjustments—such as lengthening the amount of time an asylum seeker had to wait to receive a

work permit, or requiring more extensive information

on visa applications. Donald Trump was the only

presidential candidate in modern U.S. history to run

and win on an immigration-centered platform. And

while his administration may not have delivered on

his most extreme promises, such as deporting millions

of unauthorized immigrants or building a wall along

the entire, 2,000-mile U.S.-Mexico border, changes to

the immigration system during his tenure—some of which are likely to remain on the books for years to

come—successfully narrowed grants of humanitarian protection, increased enforcement, and made legal

immigration more dicult. These actions were often carried out in the name of protecting U.S. national

security and promoting economic advancement for U.S. workers.

This transformation was made possible by the increasing power of the executive branch in immigration

policymaking. Congress has failed for decades to update the country’s immigration laws; at the same time,

Americans and their elected ocials of all political allegiances believe the immigration system is broken

and want change. A vacuum has thus opened that the executive branch has lled in recent years, with little

chance of Congress pushing back. Trump was the rst president to take full advantage of this vacuum to

advance an extensive policy agenda across the immigration system.

This report chronicles the immigration actions, large and small, that President Trump and his administration

took throughout the four years of his presidency. It is a nal update to work originally published in July

2020, which catalogued the administration’s actions through its rst three years.

2

This compendium covers

the period from January 20, 2017, through January 20, 2021. It is a snapshot of the immigration system

as it stood when Trump departed the White House, and thus it does not include any changes to Trump

administration policies—imposed either by the courts or by subsequent administrations—that occurred

beyond this period.

1 This exercise of cataloging the many actions related to immigration taken by the Trump administration has beneted from the

time and expertise of many colleagues. Sarah Pierce, one of this report’s coauthors, is no longer an analyst at the Migration Policy

Institute (MPI) and her work on this project occurred while she was still at the institute.

2 Sarah Pierce and Jessica Bolter, Dismantling and Reconstructing the U.S. Immigration System: A Catalog of Changes under the Trump

Presidency (Washington, DC: MPI, 2020).

The Trump administration set an

unprecedented pace for executive

action on immigration. In four years,

it completed 472 executive actions

aecting U.S. immigration policy.

MIGRATION POLICY INSTITUTE | 2 MIGRATION POLICY INSTITUTE | 3

FOUR YEARS OF PROFOUND CHANGE: IMMIGRATION POLICY DURING THE TRUMP PRESIDENCY FOUR YEARS OF PROFOUND CHANGE: IMMIGRATION POLICY DURING THE TRUMP PRESIDENCY

A. What Has Changed?

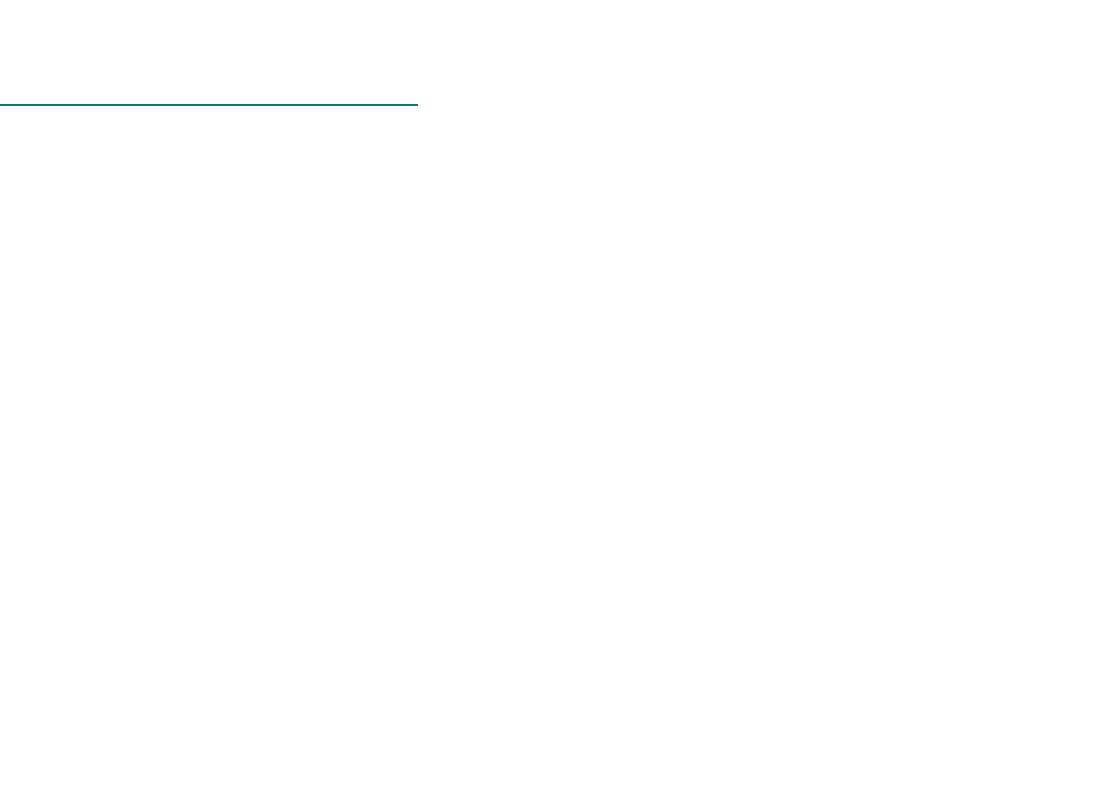

The Trump administration made changes across the immigration system, with a plurality relating to the

agencies involved in granting immigration benets—U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS)

and the Department of Labor (see Figure 1). Indeed, Trump’s election brought into mainstream political

discourse the previously fringe idea that legal immigration is a threat to the United States’ economy and

security. USCIS was increasingly tasked with immigration enforcement duties: the number of charging

documents it issued, which enter immigrants into removal proceedings, increased by 52 percent from

scal year (FY) 2016 to FY 2019, from 92,000 to 140,000.

3

Chilling eects from increased enforcement and

new barriers to applying for immigration benets contributed to 17 percent fewer immigrants submitting

applications for permanent residence in the United States in FY 2019, and 22 percent fewer in FY 2020, than

in FY 2016. And changes made to the public-charge grounds on which a noncitizen could be considered

inadmissible, implemented both at USCIS and the State Department, made it more dicult for lower-

income immigrants to come to and stay in the United States, and likely had a disproportionate impact on

women, the elderly, children, and migrants from Mexico and Central America.

4

FIGURE 1

Executive Actions on Immigration Taken during the Trump Presidency, by Category, 2017–21

Pandemic

Response

17%

Immigration

Enforcement

18%

Department of

Justice

15%

Humanitarian

Migration

18%

Department of

State

8%

U.S. Citizenship and

Immigration Services &

Department of Labor

22%

Other Actions

2%

Note: In this gure, “pandemic response” includes all pandemic-related actions, regardless of policy area. For other categories, actions

that could be classied in multiple ways are counted in their primary policy area, so there is no double-counting.

Source: Author analysis of actions described in this report.

3 Mike Guo, Immigration Enforcement Actions: 2019 (Washington, DC: Department of Homeland Security, 2020).

4 Jeanne Batalova, Michael Fix, and Mark Greenberg, “Millions Will Feel Chilling Eects of U.S. Public-Charge Rule That Is Also Likely

to Reshape Legal Immigration” (commentary, MPI, Washington, DC, August 2019).

MIGRATION POLICY INSTITUTE | 2 MIGRATION POLICY INSTITUTE | 3

FOUR YEARS OF PROFOUND CHANGE: IMMIGRATION POLICY DURING THE TRUMP PRESIDENCY FOUR YEARS OF PROFOUND CHANGE: IMMIGRATION POLICY DURING THE TRUMP PRESIDENCY

Perhaps Trump’s strongest rhetoric was reserved for immigration enforcement, at U.S. borders and in

the interior of the country. Even so, his presidency in FY 2019 witnessed the highest number of migrant

apprehensions at the southwest border since FY 2007.

5

In response, the U.S. Department of Homeland

Security (DHS) instituted a combination of interlocking policies that signicantly limited asylum at the

border, at the same time successfully pressuring Mexico to increase its own immigration enforcement.

6

These policies included a regulation making migrants ineligible for asylum if they failed to apply for it

elsewhere en route to the United States, Asylum Cooperative Agreements with Central American countries

allowing the United States to send asylum seekers abroad, and a ramping up of the Migrant Protection

Protocols (MPP, also known as Remain in Mexico), requiring migrants, mainly asylum seekers, to wait in

Mexico for their U.S. immigration court adjudications. Together, the policy regime blocked asylum access or

eligibility for the vast majority of asylum seekers and contributed to a decrease in arrivals at the U.S.-Mexico

border.

In 2020, the pandemic gave the administration the opportunity to further close o the border. Invoking the

power given to the surgeon general in 1944 to block the entry of foreign nationals who pose a public-health

risk, the director of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) issued an order on March 20,

2020, mandating that all foreign nationals without authorization to enter the United States be pushed back

to Mexico (or Canada) or returned to their countries. Under the order, and as mobility restrictions spiked

worldwide, encounters at the border initially dropped and asylum applications at the border plummeted, as

the few who did arrive were expelled without the opportunity to seek refuge.

7

However, border encounters

rose again through the summer and fall of 2020. While the Trump administration implemented some of the

most restrictive border policies in U.S. history, with life-changing impacts on many migrants who arrived

at the border, periodic and dramatic increases in arrivals at the border continued because the underlying

factors that push migrants to leave Central America and Mexico and that draw them to the United States

remained unaddressed.

In the U.S. interior, the administration’s policies centered on enacting the maximum penalty for any

removable noncitizen, with few exceptions. A January 2017 executive order eectively made every

unauthorized immigrant a priority for arrest. However, with resources and policy focus drawn to the border,

and pushback from some jurisdictions limiting the ability of U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement

(ICE) to work with local law enforcement, interior immigration arrests and removals ultimately decreased

in comparison to the prior four years under the Obama administration. ICE made 549,000 arrests from FY

2017 through FY 2020, compared to 640,000 from FY 2013 through FY 2016. Similarly, it removed 935,000

noncitizens from the country during Trump’s term in oce, compared to 1,160,000 in the prior four years.

8

5 U.S. Border Patrol, “Southwest Border Sectors: Total Encounters by Fiscal Year,” accessed October 8, 2021.

6 Muzaar Chishti and Jessica Bolter, “Interlocking Set of Trump Administration Policies at the U.S.-Mexico Border Bars Virtually All

from Asylum,” Migration Information Source, February 27, 2020.

7 MPI analysis of U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS), “Semi-Monthly Credible Fear and Reasonable Fear Receipts and

Decisions,” updated June 22, 2020.

8 U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE), U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement Fiscal Year 2020 Enforcement and

Removal Operations Report (Washington, DC: ICE, n.d.); U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement Fiscal Year 2019 Enforcement

and Removal Operations Report (Washington, DC: ICE, n.d.); ICE, Fiscal Year 2018 ICE Enforcement and Removal Operations Report

(Washington, DC: ICE, n.d.); ICE, Fiscal Year 2017 ICE Enforcement and Removal Operations Report (Washington, DC: ICE, n.d.);

ICE, Fiscal Year 2016 ICE Enforcement and Removal Operations Report (Washington, DC: ICE, 2016); Bryan Baker and Christopher

Williams, Immigration Enforcement Actions: 2015 (Washington, DC: DHS, 2017); Randy Capps et al., Revving Up the Deportation

Machinery: Enforcement under Trump and the Pushback (Washington, DC: MPI, 2018).

MIGRATION POLICY INSTITUTE | 4 MIGRATION POLICY INSTITUTE | 5

FOUR YEARS OF PROFOUND CHANGE: IMMIGRATION POLICY DURING THE TRUMP PRESIDENCY FOUR YEARS OF PROFOUND CHANGE: IMMIGRATION POLICY DURING THE TRUMP PRESIDENCY

But even as the number of arrests and removals decreased, the broader net cast by the administration’s

enforcement eorts showed through. The noncriminal share of noncitizens arrested by ICE more than

doubled over the course of the Trump administration: in FY 2020, 32 percent of those arrested had never

been convicted of a crime compared to 14 percent in FY 2016.

9

The backlog of more than 1 million cases in the immigration court system also haunted the administration’s

eorts to scale up removals. Yet, by placing a massive amount of pressure on the courts—to the point

of raising concerns about due process implications—the administration started to increase the pace of

adjudications.

10

Between FY 2016 and FY 2020, the total number of cases adjudicated per year rose 61

percent, from 143,000 to 232,000 (even with the intermittent closures of immigration courts in 2020 due

to the COVID-19 pandemic), and the total number of deportation orders per year (including both removal

orders and voluntary departures) rose by 102 percent, from 90,000 in FY 2016 to 181,000 in FY 2020.

11

The administration’s attempts to end Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA), a program providing

protection from deportation and work authorization to unauthorized immigrants brought to the United

States as children, were thwarted by federal courts. In January 2018, a court mandate ordered USCIS to

continue adjudications, though this applied only to existing DACA participants and left out new applicants.

The Migration Policy Institute (MPI) estimates that between September 2017—when the administration

stopped accepting new applicants—and July 2020, as many as 500,000 young foreign nationals who met

eligibility criteria for DACA were unable to apply, including 66,000 who became eligible during that time.

12

The U.S. Supreme Court ruled in June 2020 that the administration’s attempt to end DACA violated federal

law, and in July 2020 a federal court ordered USCIS to consider applications from new applicants.

13

However,

the administration in short order implemented a new approach to DACA as of July 28, 2020: deny all rst-

time applications, and grant renewals for one year rather than two-year periods, while undertaking a review

of the program as a whole.

14

In December 2020, a federal court ordered the administration to restore DACA

to its original form, once again allowing new applicants to request benets.

15

9 ICE, U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement Fiscal Year 2020 Enforcement and Removal Operations Report; ICE, Fiscal Year 2016

ICE Enforcement and Removal Operations Report.

10 Executive Oce for Immigration Review (EOIR), “Pending Cases, New Cases, and Total Completions,” updated October 19, 2021;

Sarah Pierce, “As the Trump Administration Seeks to Remove Families, Due-Process Questions over Rocket Dockets Abound”

(commentary, MPI, Washington, DC, July 2019).

11 MPI analysis of data from EOIR, “New Cases and Total Completions - Historical,” updated October 19, 2021; Transactional Records

Access Clearinghouse (TRAC) Immigration, “Outcomes of Deportation Proceedings in Immigration Court,” accessed October 8,

2021.

12 Post by MPI on Twitter, June 18, 2020; MPI calculations based on Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) immediately

eligible population, July 2020.

13 Department of Homeland Security v. Regents of the University of California, No. 18-587 (Supreme Court of the United States, June

18, 2020); Casa de Maryland v. Department of Homeland Security, No. PWG-17-2942 (U.S. District Court for the District of Maryland,

July 17, 2020).

14 The administration also decided to deny DACA recipients’ requests for advance authorization to travel (i.e., advance parole),

except in exceptional circumstances. Memorandum from Chad Wolf, Acting Secretary of Homeland Security, to Mark Morgan,

Senior Ocial Performing the Duties of Commissioner, U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP); Matthew Albence, Senior

Ocial Performing the Duties of Director, ICE; and Joseph Edlow, Deputy Director of Policy, USCIS, Reconsideration of the June

15, 2012 Memorandum Entitled “Exercising Prosecutorial Discretion with Respect to Individuals Who Came to the United States as

Children”, July 28, 2020.

15 Batalla Vidal, et al., v. Wolf, et al. and State of New York, et al., v. Trump, et al., Nos. 16-CV-4756 (NGG) (VMS) and 17-CV-5228 (NGG)

(VMS) (U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of New York, December 4, 2020).

MIGRATION POLICY INSTITUTE | 4 MIGRATION POLICY INSTITUTE | 5

FOUR YEARS OF PROFOUND CHANGE: IMMIGRATION POLICY DURING THE TRUMP PRESIDENCY FOUR YEARS OF PROFOUND CHANGE: IMMIGRATION POLICY DURING THE TRUMP PRESIDENCY

Finally, humanitarian forms of admission were the target of some of the administration’s most focused

eorts to curtail immigration. Refugee admissions dropped to 11,814 in FY 2020, down from 84,994 in FY

2016, reaching the lowest level since the modern U.S. refugee resettlement program began in 1980.

16

The

low level of admissions in FY 2020 was partly due to the pandemic, but two years prior, in FY 2018, the

Trump administration had set the same record; the 22,560 refugee admissions that year represented the

lowest number since 1980 up to that point. While refugees are selected to receive protection in the United

States while they wait in third countries, migrants who arrive in the United States with another immigration

status or without any status can seek asylum if they fear persecution on certain grounds in their origin

country. Under the Trump administration, the share of asylum applications approved in immigration courts

decreased from 43 percent in FY 2016 to 26 percent in FY 2020.

17

B. Driving Reform through Layered Changes

The Trump administration delivered on its aims by maintaining a rapid-re pace and layering each initiative

with a series of regulatory, policy, and programmatic changes. For example, beginning with a single

measure, a 2019 regulation from USCIS barring foreign nationals who receive or are deemed likely to

receive public benets from becoming legal permanent residents, the administration may have signicantly

changed the face of U.S. immigration. MPI analysis found that the “public-charge” regulation put a large

share of green-card applicants at risk of denial: among recent green-card recipients, 69 percent had at least

one of the characteristics weighed negatively under the regulation.

18

But despite the concentrated power of this one regulation, it was only one among a broad set of policies

introduced with the aim of discouraging public benets use, with a disproportionate impact on lower-

income immigrants. Others included:

16 MPI analysis of data from Refugee Processing Center, “Admissions and Arrivals—Refugee Admissions Report,” accessed October 8,

2021.

17 MPI analysis of data from EOIR, “Asylum Decision Rates,” updated July 8, 2021.

18 Batalova, Fix, and Greenberg, “Millions Will Feel Chilling Eects.”

► A 2018 change to guidance for State Department consular ocers, which went into eect before the

later public-charge regulation was issued, encouraging them to consider a broader range of criteria to

determine whether a visa applicant is likely to become a public charge (see Section 6).

► A separate 2019 public-charge regulation published by the State Department that mirrors USCIS’s, but

that is to be applied to all would-be immigrants outside of the United States (see Section 6).

► The 2019 elimination of proof of receipt of a means-tested benet as a way to qualify for a fee waiver

for an immigration benets application or for biometric services (see Section 7).

► A 2019 presidential memorandum ordering the administration to begin enforcing the nancial

commitments of immigrant sponsors, who pledge to reimburse the government should the

immigrants they sponsor receive means-tested public benets. The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid

Services and the U.S. Department of Agriculture subsequently issued guidance encouraging state

agencies to seek such reimbursements (see Section 7).

MIGRATION POLICY INSTITUTE | 6 MIGRATION POLICY INSTITUTE | 7

FOUR YEARS OF PROFOUND CHANGE: IMMIGRATION POLICY DURING THE TRUMP PRESIDENCY FOUR YEARS OF PROFOUND CHANGE: IMMIGRATION POLICY DURING THE TRUMP PRESIDENCY

► A 2019 presidential proclamation stating that all new immigrants could be denied entry into the

country unless they prove that they can obtain eligible health insurance within 30 days or that they

will have sucient resources to pay for foreseeable medical costs (see Section 6).

► A 2020 regulation by the Social Security Administration that removed lack of English prociency as a

factor that can help make someone eligible for Social Security disability insurance (see Section 8).

► A regulation proposed by the Department of Housing and Urban Development in 2019 that, had it

been enacted, would have prevented unauthorized immigrants from living in subsidized housing,

even if they were in mixed-status families where other members were eligible (see Section 8).

This layered approach helped insulate the administration’s goals from court injunctions. For example,

while the president’s proclamation requiring proof of health insurance before admission was enjoined, the

State Department’s public-charge guidance and regulation as well as another policy change attempting

to prevent “birth tourism” ensured that consular ocers would continue to look at applicants’ health

conditions and conrm they had the means to pay for treatment before granting them a visa.

This multifaceted strategy and brisk pace also made it dicult for opponents of the administration’s policies

to keep up and counter each measure. While immigrant advocacy organizations were quick to challenge the

USCIS public-charge regulation in court, they had fewer resources available to track and oppose measures

with a smaller impact, such as changes in the factors weighed in Social Security Administration disability

insurance determinations.

While many of the administration’s changes appear small and technical, in combination they had much

larger impacts on the U.S. immigration system. For example, in January 2018 the State Department quietly

revised its consular manual to empower ocers to limit the period for which nonimmigrant visas are valid.

Previously, ocers were encouraged to issue

visas for the full available validity period, typically

ten years. This meant that nonimmigrants,

such as students and tourists, had visa stamps

that expired more quickly and had to apply for

renewals more often. As such, foreign nationals

were subject more frequently to other Trump

administration changes that increased vetting, including requirements that they disclose more information

about themselves (e.g., social media usernames and previous email addresses), public-charge review, and

expanded consideration of whether they ever violated the terms of their nonimmigrant status.

The technical nature of many of these changes reected the administration’s knowledge of and willingness

to enforce the many immigration laws and regulations in place that have rarely if ever been put into

practice, but that have the potential to greatly restrict immigration and increase enforcement. For example,

the administration put into force provisions from the 1996 Illegal Immigration Reform and Immigrant

Responsibility Act that previously had not been implemented. Under statutory authority created by that

law, DHS created and began implementing Remain in Mexico. Also under a provision of the 1996 law,

ICE began levying nes of up to $813 per day for unauthorized immigrants who remained in the country

While many of the administration’s

changes appear small and technical,

in combination they had much larger

impacts on the U.S. immigration system.

MIGRATION POLICY INSTITUTE | 6 MIGRATION POLICY INSTITUTE | 7

FOUR YEARS OF PROFOUND CHANGE: IMMIGRATION POLICY DURING THE TRUMP PRESIDENCY FOUR YEARS OF PROFOUND CHANGE: IMMIGRATION POLICY DURING THE TRUMP PRESIDENCY

in violation of a removal order. The administration also stretched the application of laws prohibiting the

harboring of unauthorized immigrants in an attempt to withhold federal grants from jurisdictions that limit

their cooperation with federal immigration enforcement agencies. And it consistently argued that, out of

a responsibility to enforce the law to the fullest extent, ICE should not apply prosecutorial discretion to

protect certain noncitizens—such as those awaiting the adjudication of immigration benets applications—

from removal, and that U.S. attorneys should prosecute as many migrants who cross the border illegally as

possible.

The administration also ventured into uncharted territory in immigration policymaking, testing the outer

bounds of what the executive branch can do on immigration unilaterally. At rst, the courts regularly slowed

or blocked the administration’s eorts. But as time went on, and especially in 2019 as cases reached higher

courts, the Justice Department’s legal arguments began to gain traction, and judges increasingly showed

deference to the executive’s authority in immigration matters. In 2019, the Supreme Court overruled

injunctions against the transit-country asylum ban, MPP, the use of billions of dollars in diverted Pentagon

funding for a border wall, and USCIS’s public-charge regulation. An appeals court also lifted an injunction

preventing the Justice Department from limiting federal grant funding for sanctuary cities. And in 2020,

while the Supreme Court did not allow the administration’s attempt to terminate DACA to go into eect,

it made clear that the administration did have the authority to end DACA—it just had to follow proper

procedures to do so.

Not hesitating to employ the full breadth of the executive’s powers to further its immigration agenda, the

administration also took advantage of a wide range of foreign policy tools. It banned travel from certain

countries to push them to make changes to their internal security and identity-management measures,

and it denied visas to nationals of other countries to pressure their governments to accept their citizens

when ordered removed from the United States. Under the threat of taris, the president convinced Mexico

to increase its own enforcement of immigration laws and participate in MPP. And over the course of 2019,

DHS got three of the top ve origin countries for those seeking asylum in the United States—El Salvador,

Guatemala, and Honduras—to agree to allow the U.S. government to send some asylum seekers to these

countries to seek protection there.

C. Pushback and the Search for Alternatives

As the administration pushed ahead with its immigration agenda, resistance seemed in some ways to lose

steam. The rst two years of the Trump administration saw widespread protests, including against the

travel ban in 2017 and family separations at the U.S.-Mexico border in 2018. But despite implementing a

policy regime in 2019 and 2020 that eectively ended asylum at the southern border, public pushback

was more limited. Still, some civil-society groups continued to expand “Know Your Rights” education and

legal assistance, at times backed by local government funds. Employees at a handful of large technology

companies also protested their employers’ contracts with federal immigration agencies, though few of these

eorts succeeded in changing the companies’ decisions.

19

19 Muzaar Chishti and Jessica Bolter, “‘Cubicle Activism’: Companies Face Growing Demands from Workers to Cut Ties with ICE and

Others in Immigration Arena,” Migration Information Source, October 30, 2019.

MIGRATION POLICY INSTITUTE | 8 MIGRATION POLICY INSTITUTE | 9

FOUR YEARS OF PROFOUND CHANGE: IMMIGRATION POLICY DURING THE TRUMP PRESIDENCY FOUR YEARS OF PROFOUND CHANGE: IMMIGRATION POLICY DURING THE TRUMP PRESIDENCY

While congressional inaction and resistance thwarted some of Trump’s legislative goals, his administration

often found ways around these obstacles. After Congress repeatedly refused the president’s outsized

spending asks, the administration procured money for enforcement, including immigrant detention and

the border wall, through an emergency declaration, fees on legal immigrants, and transfers of otherwise

appropriated funds. Congress did come together to formally rebuke the president on three immigration

policies: (1) it twice passed legislation to block the president’s emergency declaration for wall funding,

which the president vetoed both times; (2) it restricted ICE from using information on sponsors of

unaccompanied children for immigration enforcement; and (3) it reversed a USCIS policy that made it more

dicult for about two dozen children born to U.S. military members serving abroad to receive citizenship.

Congress also passed a bill, which the president signed, that made several thousand Liberian immigrants

with temporary protection from deportation eligible for legal permanent residence. But on the hundreds of

other policy changes documented in this report, Congress was eectively silent.

Some states and localities continued to resist the administration’s immigration agenda, particularly its

enforcement eorts. For example, New York State implemented a law in December 2019 that, in addition

to making unauthorized immigrants eligible to receive driver’s licenses, cuts o federal immigration

enforcement agencies’ access to the state Department of Motor Vehicles (DMV) database (though it was

later amended to allow for limited information sharing). A May 2019 law in Washington State prohibited

state and local law enforcement from conducting enforcement solely to determine immigration status and

limited information sharing with federal authorities. The administration worked to undermine such eorts

to help unauthorized immigrants feel safe by increasing at-large operations in sanctuary communities—

arresting noncitizens outside of the criminal justice system, including at home, at work, or out in the

community. Still, the lack of cooperation from some major state and local governments signicantly

disrupted the administration’s interior enforcement eorts, contributing to its inability to reach prior arrest

and removal levels.

D. Cataloging a Period of Intense Change

In an attempt to chronicle both the transformation of the U.S. immigration system and how it was achieved

during this historic period, this report documents the 472 immigration-related policy changes the Trump

administration made during its four years in oce, the last of which included the onset of the COVID-19

pandemic.

20

The sections that follow break these many changes down by issue area, starting with the administration’s

coronavirus response, followed by border and interior enforcement; actions involving the Department

of Justice and the immigration court system; the admission of refugees, asylum seekers, and other

humanitarian migrants; and changes to vetting and visa processes, which involve the State Department,

USCIS, and the Department of Labor.

20 The other major eort to track immigration actions during the Trump administration counted 1,059 total changes; see Lucas

Guttentag, “Immigration Policy Tracking Project,” accessed January 15, 2022. Because MPI’s methodology sometimes groups

together multiple smaller changes under a thematic umbrella, this report’s total number is smaller. For example, the USCIS

policy instructing ocers to increase issuances of notices to appear, or NTAs, is counted as one action by MPI (see Section

7) but three by the Immigration Policy Tracking Project: once when the policy memorandum was issued, once when USCIS

announced it would continue implementing the policy, and once when the policy was expanded to include applicants for certain

humanitarian immigration benets.

MIGRATION POLICY INSTITUTE | 8 MIGRATION POLICY INSTITUTE | 9

FOUR YEARS OF PROFOUND CHANGE: IMMIGRATION POLICY DURING THE TRUMP PRESIDENCY FOUR YEARS OF PROFOUND CHANGE: IMMIGRATION POLICY DURING THE TRUMP PRESIDENCY

2 Pandemic Response

As the COVID-19 pandemic spread across the globe in early 2020, the Trump administration put in place a

sweeping response in the immigration sphere. While many measures were necessary and proportionate to

this crisis, others introduced dramatic changes that may have done more to advance the administration’s

longstanding immigration goals than to halt the spread of the virus. The pandemic response touched

each part of the U.S. immigration system and included some of the administration’s boldest actions

on immigration: a ban on travel from 31 countries, a suspension of immigration for most family- and

employment-based visa categories and four temporary worker programs, and the invocation of a 1944

public-health statute allowing the U.S. government to expel migrants at the border without providing

access to the asylum system. The White House also negotiated agreements with Mexico and Canada to limit

travel across shared borders to essential trac.

Three particular actions allowed the

administration to accomplish goals it was

working toward prior to the pandemic. After

two years of the administration making it more

dicult to apply for asylum and narrowing

the eligibility criteria for the few who were

able to apply, the March 2020 order to expel

unauthorized arrivals, issued by the director of

the CDC, eectively ended asylum at the U.S.

southern border. The president’s April proclamation suspending certain categories of immigration mirrored

earlier attempts by the administration to convince Congress to limit family migration, as 80 percent of the

blocked immigrants came from family-based categories.

21

It also eectively ended the Diversity Visa Lottery,

another program the administration had pushed Congress to quash. The June proclamation suspending

some temporary work programs included visas—such as the H-1B—that the administration had spent

years scrutinizing for fraud. The pandemic thus presented opportunities, in the name of public health, to

unilaterally restrict entry.

Inside the United States, meanwhile, the administration’s management of response policies aecting

immigrants and their communities was uneven at best. ICE narrowed its enforcement priorities, focusing

on arresting and detaining noncitizens who posed a public safety risk or had serious criminal records.

From April through December 2020, ICE booked into detention an average of 6,000 immigrants monthly,

compared to a monthly average of 11,000 during the same period in 2019.

22

However, COVID-19 still spread

quickly in detention facilities: on average, between April and August 2020, ICE detainees were 13 times

more likely to contract the virus than the U.S. general population.

23

U.S. immigration courts also continued

their operations during the pandemic. Despite repeated calls from immigration judges, attorneys, and even

21 MPI analysis of data from U.S. Department of Homeland Security (DHS), “Table 7. Persons Obtaining Lawful Permanent Resident

Status by Type and Detailed Class of Admission: Fiscal Year 2018,” updated January 16, 2020.

22 MPI analysis of data from ICE, “Detention Management—Detention Statistics, FY 2019-2021,” updated December 29, 2021.

23 Parsa Erfani et al., “COVID-19 Testing and Cases in Immigration Detention Centers, April-August 2020,” Journal of the American

Medical Association 325, no. 2 (2021): 182–84.

While many measures were necessary

and proportionate to this crisis, others

introduced dramatic changes that

may have done more to advance the

administration’s longstanding immigration

goals than to halt the spread of the virus.

MIGRATION POLICY INSTITUTE | 10 MIGRATION POLICY INSTITUTE | 11

FOUR YEARS OF PROFOUND CHANGE: IMMIGRATION POLICY DURING THE TRUMP PRESIDENCY FOUR YEARS OF PROFOUND CHANGE: IMMIGRATION POLICY DURING THE TRUMP PRESIDENCY

ICE prosecutors to completely shut down the courts, the Executive Oce for Immigration Review (EOIR)

refrained from doing so, instead limiting hearings to foreign nationals who were detained. Finally, closures

of USCIS oces and Application Support Centers caused a signicant slowdown in legal immigration

processes. The USCIS backlog grew 11 percent between December 2019 and December 2020, when it

reached 6.4 million cases.

24

In comparison, it had grown 2 percent and 4 percent during the same period in

each of the prior two years.

25

A. Travel Bans and Visa Processing

The U.S. Department of State, which is responsible for the adjudication of visa applications and

dissemination of visa stamps to foreign nationals seeking to enter the United States, suspended routine

visa services on March 18, 2020. While this step protected consulate and embassy sta and visitors from

contracting COVID-19, it also sharply curtailed visa issuance. U.S. immigrant visa issuance abroad decreased

35 percent between February and March 2020, as global travel started to slow, and then dropped 94 percent

between March and April following the consular closures.

26

Even though the State Department permitted

consulates and embassies to start reopening in July, they were not able to reach full capacity; by January

2021, one-third of diplomatic posts still had not scheduled a single immigrant visa interview.

27

The State Department is also responsible for enforcing coronavirus-related travel and immigration

restrictions. Under the Trump administration, this included the president’s ban on foreign nationals traveling

from 31 countries (exempting U.S. permanent residents), most employment- and family-based immigration,

and nonimmigrants on certain temporary work visas. The consular closures coupled with these bans made

FY 2020 one of the lowest years of in-migration in recent history. The number of immigrant visas issued

abroad in FY 2020 dipped 48 percent from a year earlier, and the number of temporary (nonimmigrant) visas

issued decreased 54 percent.

28

While those waiting for immigrant visas had to wait a little longer to be able

to immigrate permanently to the United States, it is likely that many of those who were unable to receive

temporary visas were fully blocked from coming to the country as oers for temporary employment could

have expired.

24 USCIS, “Number of Service-Wide Forms by Quarter, Form Status, and Processing Time. Fiscal Year 2021, Quarter 1,” accessed

October 10, 2021; USCIS, “Number of Service-Wide Forms Fiscal Year to Date by Quarter and Form Status, Fiscal Year 2020,”

accessed October 10, 2021.

25 USCIS, “Number of Service-Wide Forms Fiscal Year to Date by Quarter and Form Status, Fiscal Year 2020”; USCIS, “Number of

Service-Wide Forms by Fiscal Year to Date, Quarter, and Form Status. 2019,” accessed October 10, 2021; USCIS, “Number of

Service-Wide Forms by Fiscal Year to Date, Quarter, and Form Status. 2018,” accessed October 10, 2021.

26 Muzaar Chishti and Jessica Bolter, “The ‘Trump Eect’ on Legal Immigration Levels: More Perception than Reality?” Migration

Information Source, November 20, 2020.

27 Bob Ortega, “Huge Trump-Era and Pandemic Immigrant Visa Backlog Poses Challenge for Biden,” CNN, April 12, 2021.

28 MPI analysis of U.S. Department of State, “Monthly Nonimmigrant Visa Issuance Statistics,” accessed September 29, 2021; MPI

analysis of U.S. Department of State, “Monthly Immigrant Visa Issuance Statistics,” accessed September 29, 2021.

► Geographical COVID-19 Travel Bans—2020—Trump issued proclamations banning entries of foreign

nationals from areas with high rates of COVID-19 transmission.

J Ban on Travel from China—January 31, 2020—Trump issued a proclamation banning the entry

of foreign nationals, with signicant exceptions, who were in mainland China during the 14

MIGRATION POLICY INSTITUTE | 10 MIGRATION POLICY INSTITUTE | 11

FOUR YEARS OF PROFOUND CHANGE: IMMIGRATION POLICY DURING THE TRUMP PRESIDENCY FOUR YEARS OF PROFOUND CHANGE: IMMIGRATION POLICY DURING THE TRUMP PRESIDENCY

days preceding their intended entry to the United States.

29

Foreign nationals subject to the

ban are prevented from being granted visas, boarding airplanes destined for the United States,

and entering at U.S. ports of entry.

J Ban on Travel from Iran—February 29, 2020—The president issued a proclamation banning

the entry of foreign nationals, with signicant exceptions, who were in Iran during the 14 days

preceding their intended entry to the United States.

30

J Ban on Travel from the Schengen Area of Europe—March 1, 2020—In one proclamation, the

president banned the entry of foreign nationals, with signicant exceptions, who were in one

of the 26 European countries comprising the Schengen Area during the 14 days preceding

their intended entry to the United States.

31

The State Department exempted people with

student visas from this ban on July 16, 2020.

32

J Ban on Travel from the United Kingdom and Ireland—March 14, 2020—Trump issued a

proclamation banning the entry of foreign nationals, with signicant exceptions, who were

in the United Kingdom or Ireland during the 14 days preceding their intended entry to the

United States.

33

The State Department exempted people with student visas from this ban on

July 16, 2020.

34

J Ban Exemption for Professional Athletes—May 23, 2020—Acting Secretary of DHS Chad Wolf

issued a statement declaring that professional athletes are exempt from the president’s bans

on travel from countries with high rates of COVID-19 transmission, citing the “national interest

exemption.”

35

J Ban on Travel from Brazil—May 24, 2020—The president issued a proclamation banning the

entry of foreign nationals, with signicant exceptions, who were in Brazil during the 14 days

29 White House, “Proclamation 9984 of January 31, 2020: Suspension of Entry as Immigrants and Nonimmigrants of Persons Who

Pose a Risk of Transmitting 2019 Novel Coronavirus and Other Appropriate Measures to Address This Risk,” Federal Register 85, no.

24 (February 5, 2020): 6709–12.

30 White House, “Proclamation 9992 of February 29, 2020: Suspension of Entry as Immigrants and Nonimmigrants of Certain

Additional Persons Who Pose a Risk of Transmitting 2019 Novel Coronavirus,” Federal Register 85, no. 43 (March 4, 2020): 12855–

58. The administration also restricted all ights carrying travelers from the banned countries to landing at 11 designated airports.

See CBP and Transportation Security Administration (TSA), “Notication of Arrival Restrictions Applicable to Flights Carrying

Persons Who Have Recently Traveled from or Were Otherwise Present within the People’s Republic of China or the Islamic

Republic of Iran,” Federal Register 85, no. 43 (March 4, 2020): 12731–33.

31 White House, “Proclamation 9993 of March 11, 2020: Suspension of Entry as Immigrants and Nonimmigrants of Certain

Additional Persons Who Pose a Risk of Transmitting 2019 Novel Coronavirus,” Federal Register 85, no. 51 (March 16, 2020): 15045–

48. The administration also restricted all ights carrying travelers from the banned countries to landing at 13 designated airports.

See CBP and TSA, “Notication of Arrival Restrictions Applicable to Flights Carrying Persons Who Have Recently Traveled from or

Were Otherwise Present within the Countries of the Schengen Area,” Federal Register 85, no. 52 (March 17, 2020): 15059–60.

32 U.S. Department of State, Bureau of Consular Aairs, “National Interest Exceptions for Certain Travelers from the Schengen Area,

United Kingdom, and Ireland,” updated July 16, 2020.

33 White House, “Proclamation 9996 of March 14, 2020: Suspension of Entry as Immigrants and Nonimmigrants of Certain Additional

Persons Who Pose a Risk of Transmitting 2019 Novel Coronavirus,” Federal Register 85, no. 53 (March 18, 2020): 15341–44. The

administration also restricted all ights carrying travelers from the banned countries to landing at 13 designated airports. See

CBP and TSA, “Notication of Arrival Restrictions Applicable to Flights Carrying Persons Who Have Recently Traveled from or Were

Otherwise Present within the United Kingdom or the Republic of Ireland,” Federal Register 85, no. 54 (March 19, 2020): 15714–15.

34 U.S. Department of State, Bureau of Consular Aairs, “National Interest Exceptions for Certain Travelers.”

35 DHS, “National Interest Exemption from Presidential Proclamations 9984, 9992, 9993, and 9996 Regarding Novel Coronavirus for

Certain Professional Athletes and Their Essential Sta and Dependents” (guidance document, May 23, 2020).

MIGRATION POLICY INSTITUTE | 12 MIGRATION POLICY INSTITUTE | 13

FOUR YEARS OF PROFOUND CHANGE: IMMIGRATION POLICY DURING THE TRUMP PRESIDENCY FOUR YEARS OF PROFOUND CHANGE: IMMIGRATION POLICY DURING THE TRUMP PRESIDENCY

preceding their intended entry to the United States.

36

One day later, without explanation, the

president issued an amendment, moving the eective date of the ban from May 28 to May

26.

37

J Requirement Not to Prohibit Diversity Visa Issuance—September 14, 2020—A federal district

judge ruled that the State Department could not require diversity visa grantees living in the

banned countries to quarantine outside those countries for 14 days before issuing them their

visas.

38

J Termination of Three Bans—January 18, 2021—Trump issued a proclamation terminating the

bans on entry of foreign nationals who were in the Schengen Area, the United Kingdom or

Ireland, or Brazil in the 14 days preceding their U.S. entry, eective January 26, 2021.

39

► Refugee Resettlement Interviews Curtailed and Cancelled—March 2020—Overseas trips by USCIS

ocers to interview refugees for resettlement (called “circuit rides”) that were in progress in mid-March

were cut short, and the rest of the scheduled circuit rides for the scal year were cancelled.

40

► Exclusion of Students in Online-Only Programs—2020–21—On March 9, 2020, ICE, which manages

the Student and Exchange Visitor Program (SEVP), announced exibility with online courses, advising

that nonimmigrant students could maintain their status even if all of their courses were online, but

that this did not apply to new students.

41

On July 24, 2020, ICE further claried that new students

would not be able to enter the United States to pursue a full course of study that is 100 percent

online.

42

(For more information, see Section 2.C.)

► Pause on International Exchange Programs—March 12, 2020—The State Department suspended

any exchange program funded by the department’s Bureau of Educational and Cultural Aairs,

including the Fulbright Program and International Visitor Leadership Program, that involves travel

to and from countries with heightened coronavirus-related advisories from the CDC or State

Department.

43

36 White House, “Proclamation 10041 of May 24, 2020: Suspension of Entry as Immigrants and Nonimmigrants of Certain Additional

Persons Who Pose a Risk of Transmitting 2019 Novel Coronavirus,” Federal Register 85, no. 103 (May 28, 2020): 31933–36. The

administration also restricted all ights carrying travelers from the banned countries to landing at 15 designated airports. See

CBP and TSA, “Notication of Arrival Restrictions Applicable to Flights Carrying Persons Who Have Recently Traveled from or Were

Otherwise Present within the Federative Republic of Brazil,” Federal Register 85, no. 103 (May 28, 2020): 31957–58.

37 White House, “Proclamation 10042 of May 25, 2020: Amendment to Proclamation of May 24, 2020, Suspending Entry as

Immigrants and Nonimmigrants of Certain Additional Persons Who Pose a Risk of Transmitting 2019 Novel Coronavirus,” Federal

Register 85, no. 103 (May 28, 2020): 32291–92.

38 Arreguin Gomez, et al. v. Trump, et al., No. 20-cv-01419 (APM) (U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia, amended order,

September 14, 2020).

39 White House, “Proclamation 10138 of January 18, 2021: Terminating Suspensions of Entry into the United States of Aliens Who

Have Been Physically Present in the Schengen Area, the United Kingdom, the Republic of Ireland, and the Federative Republic of

Brazil,” Federal Register 86, no. 13 (January 22, 2021): 6799–801.

40 Letter from Tracy L. Renaud, Senior Ocial Performing the Duties of Director of USCIS, to Representative Gerald E. Connolly,

Chairman of the Subcommittee on Government Operations, U.S. House of Representatives, “U.S Citizenship and Immigration

Services’ Response to Chairman Connolly’s October 27, 2020 Letter,” March 2, 2021.

41 Message from Student and Exchange Visitor Program (SEVP) to all Student and Exchange Visitor Information System (SEVIS) users,

“Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) and Potential Procedural Adaptations for F and M Nonimmigrant Students,” March 9, 2020.

42 Message to all SEVIS users, “Follow-Up: ICE Continues March Guidance for Fall School Term,” July 24, 2020.

43 U.S. Department of State, “Temporary Pause of International Exchange Programs due to COVID-19” (news release, March 12,

2020).

MIGRATION POLICY INSTITUTE | 12 MIGRATION POLICY INSTITUTE | 13

FOUR YEARS OF PROFOUND CHANGE: IMMIGRATION POLICY DURING THE TRUMP PRESIDENCY FOUR YEARS OF PROFOUND CHANGE: IMMIGRATION POLICY DURING THE TRUMP PRESIDENCY

o May 12, 2020—The Bureau of Educational and Cultural Aairs suspended all remaining

international exchange programs.

44

44 U.S. Department of State, Bureau of Educational and Cultural Aairs, “Due to State Department Global Level 4 Health Advisory, All

ECA Funded In-Person Programs Will Remain Paused until Further Notice” (news release, May 12, 2020).

45 Letter from the Oce of Private Sector Exchange to J-1 Program Sponsors, Two-Month Extension of Certain Program End Dates,

March 14, 2020.

46 U.S. Department of State, “Suspension of Routine Visa Services” (news release, March 20, 2020).

47 U.S. Department of State, “Important Announcement on H2 Visas” (news release, March 26, 2020).

48 U.S. Department of State, “Update on H and J Visas for Medical Professionals” (news release, March 26, 2020).

49 Post by the State Department on Twitter, June 13, 2020.

50 Ortega, “Huge Trump-Era and Pandemic Immigrant Visa Backlog.”

51 U.S. Department of State, Bureau of Consular Aairs, “Important Notice for K Visa Applicants Aected by COVID-19” (news release,

August 31, 2020).

52 U.S. Department of State, “Phased Resumption of Routine Visa Services,” updated November 12, 2020.

► Automatic Extension for Exchange Visitors—March 14, 2020—The State Department, which

manages the J-1 exchange visitor temporary visa program, issued an automatic two-month extension

for any exchange visitors with a program end date between April 1and May 31, 2020, providing them

the opportunity to complete either their educational or training programs or nalize travel plans to

return home.

45

► Suspension of Routine Visa Services—March 18, 2020—On March 18, the State Department

suspended routine visa services in most countries and, two days later, expanded this to all countries.

46

The suspension meant that, subject to limited exceptions, foreign nationals abroad were unable to

apply for or receive the new or renewed visa stamps needed to enter the United States.

J Exception for H-2 Visas—March 26, 2020—Acknowledging H-2 visa holders as essential to the

U.S. economy and food security, the State Department announced that despite the suspension

of visa services, consulates and embassies would try to continue processing H-2A visas for

agricultural workers and H-2B visas for nonagricultural workers.

47

J Exception for Medical Professionals—March 26, 2020—The State Department announced U.S.

embassies and consulates would continue to provide visa services to the extent possible to

medical professionals seeking nonimmigrant or immigrant visas to enter the United States.

48

J Phased Reopening—July 13, 2020—The State Department announced a phased resumption

of routine visa services.

49

However, two-thirds of consular posts had not scheduled any

immigrant visa interviews by August 2020, and by January 2021, one-third still had not

scheduled any.

50

J Priority Given to K Visa Applicants—August 28, 2020—The State Department authorized

consular posts to prioritize applications for K visas (visas for ancé(e)s of U.S. citizens) as they

began to reopen.

51

J Prioritization of Additional Visa Categories—November 12, 2020—In addition to K visas, the

State Department announced that posts processing immigrant visa applications would

prioritize those of immediate relatives of U.S. citizens and certain Special Immigrant Visa

applicants.

52

Posts processing nonimmigrant visa applications would prioritize those needing

MIGRATION POLICY INSTITUTE | 14 MIGRATION POLICY INSTITUTE | 15

FOUR YEARS OF PROFOUND CHANGE: IMMIGRATION POLICY DURING THE TRUMP PRESIDENCY FOUR YEARS OF PROFOUND CHANGE: IMMIGRATION POLICY DURING THE TRUMP PRESIDENCY

to travel urgently or traveling to aid the U.S. pandemic response and diplomats, followed by

students and temporary workers.

J Fee Extension—2020—At some point in 2020, the State Department extended the validity

of visa application fee payments through December 31, 2021, so that applicants who could

not schedule an appointment due to the suspension of routine visa services would not have

to pay the fee a second time.

53

On December 30, 2020, validity was further extended through

September 30, 2022.

54

► Suspension of Refugee Resettlement—March 19, 2020—The State Department paused refugee

arrivals.

55

The pause came after the International Organization for Migration, which is in charge of

booking refugees on their travel, and the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees announced

a temporary suspension of resettlement travel.

56

On July 29, 2020, Secretary of State Michael Pompeo

approved the resumption of refugee admissions.

57

Due to the suspension of resettlement and other

pandemic-related issues, almost 7,000 of the 18,000 allotted slots for refugee admissions in FY 2020

were unused.

58

► Ban on Certain Types of Permanent Immigrants—April 22, 2020—After promising to “temporarily

suspend immigration into the United States,” Trump signed a proclamation suspending, for 60 days,

the issuance of visas to persons outside the United States who are parents, adult children, and siblings

of U.S. citizens; spouses and children of permanent residents; Diversity Visa Lottery winners; and

nearly all types of employment-based immigrants.

59

On June 22, the president issued a proclamation

suspending the entry of certain types of nonimmigrants that also extended the April 22 ban on

permanent immigrants through December 31, 2020, and on December 31, Trump extended the

April ban through March 31, 2021.

60

On September 4, 2020, a federal district judge ruled that the

administration could not prohibit the adjudication of diversity visa applications or the issuance of

diversity visas for FY 2020 under the ban.

61

On December 11, 2020, a federal district judge ruled that

the State Department could not apply the ban to the family members abroad of 181 U.S. citizens and

green-card holders who sued the government.

62

53 U.S. Department of State, “Department of State/AILA Liaison Committee Meeting,” December 11, 2020.

54 U.S. Department of State, Bureau of Consular Aairs, “Phased Resumption of Routine Visa Services” (news release, December 30,

2020).

55 Priscilla Alvarez, “Refugee Admissions to the US Temporarily Suspended,” CNN, March 18, 2020.

56 United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), “IOM, UNHCR Announce Temporary Suspension of Resettlement Travel

for Refugees” (news release, March 17, 2020).

57 Priscilla Alvarez, “Refugee Admissions to the US Resume after Being on Pause due to Coronavirus,” CNN, August 12, 2020.

58 U.S. Department of State, “Report to Congress on Proposed Refugee Admissions for Fiscal Year 2021,” accessed June 30, 2021.

59 Post by Donald Trump, President of the United States, on Twitter, April 20, 2020; White House, “Presidential Proclamation 10014

of April 22, 2020: Suspension of Entry of Immigrants Who Present a Risk to the United States Labor Market during the Economic

Recovery Following the 2019 Novel Coronavirus Outbreak,” Federal Register 85, no. 81 (April 27, 2020): 23441–44.

60 White House, “Proclamation 10052 of June 22, 2020: Suspension of Entry of Immigrants and Nonimmigrants Who Present a Risk

to the United States Labor Market During the Economic Recovery Following the 2019 Novel Coronavirus Outbreak,” Federal

Register 85, no. 123 (June 25, 2020): 38263–67; White House, “Proclamation 10131 of December 31, 2020: Suspension of Entry

of Immigrants and Nonimmigrants Who Continue To Present a Risk to the United States Labor Market During the Economic

Recovery Following the 2019 Novel Coronavirus Outbreak,” Federal Register 86, no. 3 (January 6, 2021): 417–19.

61 Arreguin Gomez, et al. v. Trump, et al., No. 20-cv-01419 (APM) (U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia, September 4, 2020).

62 Young, et al. v. Trump, et al., No. 20-cv-07183-EMC (U.S. District Court for the Northern District of California, amended order

granting plaintis’ motion for preliminary injunction and denying defendants’ motion to transfer, December 11, 2020).

MIGRATION POLICY INSTITUTE | 14 MIGRATION POLICY INSTITUTE | 15

FOUR YEARS OF PROFOUND CHANGE: IMMIGRATION POLICY DURING THE TRUMP PRESIDENCY FOUR YEARS OF PROFOUND CHANGE: IMMIGRATION POLICY DURING THE TRUMP PRESIDENCY

► Ban on Certain Types of Nonimmigrants—June 22, 2020—Trump issued a proclamation suspending

the issuance of certain types of temporary work visas through December 31, 2020.

63

The suspension

included H-1B visas, for professionals in certain high-skilled occupations; H-2B visas, for temporary

nonagricultural workers; certain categories of J visas, for summer work travel program participants

and au pairs, among others; L visas, for intracompany transferees; as well as visas issued to dependents

of nonimmigrants in these categories (i.e., holders of H-4, L-2, and J-2 visas). The proclamation was

limited to foreign nationals who were outside the United States and did not have valid visas in the

aected categories on June 24, 2020.

64

On July 16, 2020, the State Department exempted several

categories of visa holders from this ban, including spouses and children of nonimmigrant visa holders

already in the United States, some au pairs, and some health-care and public-health professionals and

medical researchers with H-1B or L-1 visas.

65

On August 12, the State Department further spelled out

who may qualify for exceptions, including H-1B and L visa applicants traveling to resume ongoing

employment and H-1B and H-2B workers who were needed to support the U.S. economic recovery,

among others.

66

On October 1, a federal district judge found that the president’s proclamation

was unlawful, and blocked its use against the plaintis who brought the legal challenge: the U.S.

Chamber of Commerce, the largest manufacturing and retail trade associations in the United States,

a cultural exchange company, and a network of technology CEOs including those of Amazon, Apple,

and Google.

67

On December 31, Trump issued a new proclamation extending the June proclamation

through March 31, 2021.

68

J Grants to Train U.S. Workers—September 24, 2020—Following the suspension of H-1B visa

issuances, the Department of Labor announced $150 million in grant funds to U.S. businesses

and organizations to upskill unemployed and underemployed U.S. workers in order to qualify

for middle- to high-skilled H-1B occupations, such as information technology and advanced

manufacturing.

69

The program will be nanced by the user fees collected from employers

participating in the H-1B visa program.

70

► Allowing Refugee Oces to Serve Fewer People—Summer 2020—The State Department lowered

its requirement that local refugee resettlement organizations must serve at least 100 refugees to

50 refugees to be eligible to resettle new arrivals since, due to the pandemic, fewer refugees were

entering the country.

71

63 White House, “Proclamation 10052 of June 22, 2020.”

64 White House, “Proclamation 10052 of June 22, 2020.”

65 U.S. Department of State, Bureau of Consular Aairs, “Exceptions to Presidential Proclamations (10014 & 10052) Suspending the

Entry of Immigrants and Nonimmigrants Presenting a Risk to the United States Labor Market during the Economic Recovery

Following the 2019 Novel Coronavirus Outbreak,” updated July 17, 2020.

66 U.S. Department of State, Bureau of Consular Aairs, “National Interest Exceptions to Presidential Proclamations (10014 &

10052) Suspending the Entry of Immigrants and Nonimmigrants Presenting a Risk to the United States Labor Market during the

Economic Recovery Following the 2019 Novel Coronavirus Outbreak,” updated August 12, 2020.

67 National Association of Manufacturers, et al. v. DHS, et al., No. 20-cv-04887-JSW (U.S. District Court for the Northern District of

California, order granting plaintis’ motion for a preliminary injunction, October 1, 2020).

68 White House, “Proclamation 10131 of December 31, 2020.”

69 U.S. Department of Labor, “U.S. Department of Labor Announces Availability of $150 Million to Invest in Workforce Training for

Key U.S. Employment Sectors” (news release, September 24, 2020).

70 U.S. Department of Labor, “H-1B One Workforce Grant Program Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs),” updated November 9, 2020.

71 National Conference on Citizenship and the Penn Biden Center for Diplomacy and Global Engagement, A Roadmap to Rebuilding

the U.S. Refugee Admissions Program (N.p.: National Conference on Citizenship and the Penn Biden Center for Diplomacy and

Global Engagement, 2020), 18.

MIGRATION POLICY INSTITUTE | 16 MIGRATION POLICY INSTITUTE | 17

FOUR YEARS OF PROFOUND CHANGE: IMMIGRATION POLICY DURING THE TRUMP PRESIDENCY FOUR YEARS OF PROFOUND CHANGE: IMMIGRATION POLICY DURING THE TRUMP PRESIDENCY

► Expansion of In-Person Interview Waiver Eligibility—August 25, 2020—The State Department made

additional nonimmigrants applying for a visa in the same classication as an expired visa eligible for

waivers of the in-person interview requirement.

72

Previously, they were only eligible if their prior visa

had expired within 12 months, but this change made them eligible if their visa had expired within 24

months. This policy was initially in eect through December 31, 2020, then extended through March

31, 2021.

73

► Requirement of Negative COVID-19 Test for UK Travelers—December 27, 2020—The CDC requires

airline passengers arriving in the United States from the United Kingdom to have tested negative for

COVID-19 in the three days prior to their ight’s departure.

74

72 U.S. Department of State, Bureau of Consular Aairs, “Expansion of Interview Waiver Eligibility” (news release, August 25, 2020).

73 U.S. Department of State, Bureau of Consular Aairs, “Expansion of Interview Waiver Eligibility” (news release, December 29,

2020).

74 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), “Requirement for Negative Pre-Departure COVID-19 Test Result for All Airline

Passengers Arriving into the United States From the United Kingdom,” Federal Register 85, no. 251 (December 31, 2020): 86933–

36.

75 CBP, “Nationwide Enforcement Encounters: Title 8 Enforcement Actions and Title 42 Expulsions,” updated August 12, 2021; CBP,

“FY2020 Nationwide Enforcement Encounters: Title 8 Enforcement Actions and Title 42 Expulsions,” updated November 20, 2020.

76 U.S. Border Patrol, “Total Illegal Alien Apprehensions by Month,” accessed October 8, 2021; CBP, “Southwest Land Border

Encounters,” updated September 15, 2021.

77 MPI analysis based on data from CBP, “Southwest Land Border Encounters.”

B. Border Security and Asylum Processing at the U.S.-Mexico Border

When the pandemic set in, U.S. border agencies were tasked with managing new travel regulations,

including the prohibition on nonessential travel across U.S. land borders and routing of ights from certain

countries to limited airports. However, the pandemic did not sway the Trump administration’s steady focus

on illegal immigration at the southern border and asylum. In one of its most sweeping actions since the

start of the public-health crisis, the administration relied on a 1944 public-health statute under Section 265

of Title 42 of the U.S. Code to issue an order barring the entry of asylum seekers and other unauthorized

arrivals at the United States’ northern and southern land borders. Through December 2020, U.S. Customs

and Border Protection (CBP) carried out more than 390,000 expulsions under this order.

75

While migration

at the U.S.-Mexico border initially slowed due to COVID-19 mobility restrictions along common migration

routes and in migrants’ origin countries, and possibly due to a deterrent eect of expulsions at the U.S.

southern border, it picked up from May 2020 onwards. Border Patrol agents encountered migrants at the

border in December 2020 more times than they had in any previous December since 1999.

76

The vast majority—88 percent—of encounters of migrants crossing the border illegally from April through

December 2020 were of single adults, rather than unaccompanied children or families.

77

In the same period

in 2019, unaccompanied children and families made up 61 percent of such encounters. Ironically, the Title

42 order, as it came to be known, incentivized more single adults to attempt to cross the border more

times. Before the implementation of Title 42, families and children apprehended at the border had some

pathways—if narrow ones—into the United States, but almost all single adults faced formal consequences.

This could include criminal prosecution and conviction, ICE detention, and formal removal from the country.

Those with convictions and removal orders on their records faced higher-level consequences if they were

apprehended trying to cross illegally again. So, for families and children, the Title 42 order cut o access

MIGRATION POLICY INSTITUTE | 16 MIGRATION POLICY INSTITUTE | 17

FOUR YEARS OF PROFOUND CHANGE: IMMIGRATION POLICY DURING THE TRUMP PRESIDENCY FOUR YEARS OF PROFOUND CHANGE: IMMIGRATION POLICY DURING THE TRUMP PRESIDENCY

to existing pathways into the United States. But for single adults, it eliminated the consequences they

previously faced. Instead of undergoing criminal or immigration proceedings, they were simply turned

around to Mexico, with no formal mark on their record. Thus, it became easier for them to attempt to cross

the border multiple times, until they could get through without getting caught.

78 DHS, “DHS Issues Supplemental Instructions for Inbound Flights with Individuals Who Have Been In China” (news release,

February 2, 2020).

79 CBP, “Notication of Termination of Arrival Restrictions Applicable to Flights Carrying Persons Who Have Recently Traveled from

or Were Otherwise Present within Certain Countries,” Federal Register 85, no. 179 (September 15, 2020): 57108–09.

80 CBP, “Frequently Asked Questions,” accessed July 16, 2021.

81 CBP, “Notication of Temporary Travel Restrictions Applicable to Land Ports of Entry and Ferries Service between the United

States and Mexico,” Federal Register 85, no. 57 (March 24, 2020): 16547–48.

82 CBP, “Notication of Temporary Travel Restrictions Applicable to Land Ports of Entry and Ferries Service between the United

States and Mexico,” Federal Register 86, no. 11 (January 19, 2021): 4967–69; CBP, “Notication of Temporary Travel Restrictions

Applicable to Land Ports of Entry and Ferries Service between the United States and Canada,” Federal Register 86, no. 11 (January

19, 2021): 4969–70.

83 Lauren Villagran, “CBP: Nonessential Travelers Will Face Greater Scrutiny at US-Mexico Border,” El Paso Times, August 21, 2020.

► Limits on Airports Receiving Flights from Banned Countries—February 2, 2020—The Acting

Secretary of DHS, Chad Wolf, issued implementing instructions for the president’s January 31, 2020,

ban on foreign nationals traveling from mainland China, instructing ights from China to route

through one of eight specied U.S. airports.

78

Seven additional airports were later added, and the

restrictions were extended to ights coming from Iran, the Schengen Area of Europe, the United

Kingdom, Ireland, and Brazil. On September 14, these airport restrictions were terminated.

79

(For

additional details on the bans and arrival limits placed on ights from various countries, see

Section 2.A.)

► Cancelation of Visa Waiver Program Participants in Violation of Presidential Proclamation—

March 16, 2020—In the wake of a presidential ban on travel from the United Kingdom and Ireland,

two countries that participate in the Visa Waiver Program, CBP announced that foreign nationals

participating in the program who attempt to travel to the United States in violation of the ban would

have their visa-free travel authorization cancelled.

80

► Restrictions on Nonessential Travel across Land Borders—March 20, 2020—After the White House

negotiated agreements with Mexico and Canada, CBP published temporary travel restrictions that

limited nonessential travel across land borders.

81

Travel deemed essential—and thus exempt from

the restrictions—included returning U.S. citizens, legal permanent residents, and members of the U.S.

armed forces, as well as travel for medical or public-health purposes, work, trade, and military-related

purposes. Initially, the restrictions were to be in place until April 20, but they were renewed monthly,

with the last renewal of the Trump administration extending through February 21, 2021.

82

J Further Scrutiny of Nonessential Travelers—In August 2020, CBP said it would increase