stradaeducation.org/nsciMAY 2024 1

Building Better

Internships

MAY 2024

Understanding and Improving the Internship Experience

stradaeducation.org/nsciMAY 2024 2

Introduction

Internships and other forms of work-based learning, long

considered essential components of a student’s education

and preparation for the workforce in other countries, are

now gaining increased recognition in the United States. Both

institutions and policymakers see the potential value of

these experiences for both students and employers.

Evidence from interdisciplinary scholars around the world,

as well as Strada’s own research on work-based learning

(and paid internships specifically), shows how internships

can positively impact individual outcomes in the labor

market after graduation.

1

For example, college students

who completed a paid internship during their undergraduate

education have higher-paying jobs after graduation, even

when accounting for differences in pay based on field of

study, gender, and race/ethnicity.

2

Graduates who completed

a paid internship also are much more likely to report having

a first job that requires a degree compared to those who did

not complete an internship, and they are more likely to be

satisfied with their first job.

3

Many students recognize the benefits of internships;

about 70 percent of first-year students plan to complete an

internship during college. Despite this interest, less than half

of students find and complete an internship, and less than a

quarter secure a paid internship.

4

State leaders also recognize the valuable role internships

can play, especially for workforce development. In 2023,

Virginia established the goal that every postsecondary

student seeking an internship is able to complete one,

and tasked a working group to study its feasibility. Along

with other activities that support this goal, the state also is

investing in public-private partnerships to provide innovative

paid internship opportunities for students. States such

as California and Indiana also have turned more attention

and funding toward the goal of expanding access to paid

internships.

5

1

Hora, Matthew T., Matthew Wolfgram, and Samantha Thompson. “What do we know about the impact of internships on student outcomes? Results from a preliminary review

of the scholarly and practitioner literatures.” Center for research on college-workforce transitions research brief 2 (2017): 1-20.

2

Nichole Torpey-Saboe, Elaine Leigh, and Dave Clayton. “The Power of Work-based Learning.” (Indianapolis: Strada Education Foundation, March 2022).

3

“State Opportunity Index.” (Indianapolis: Strada Education Foundation, April 2024); “Talent Disrupted: College Graduates, Unemployment, and the Way Forward.”

(Bala-Cynwyd, PA: The Burning Glass Institute; and Indianapolis: Strada Education Foundation, February 2024).

4

Nichole Torpey-Saboe, Sowmya Ghosh, and Dave Clayton. “From College to Career: Students’ Internship Expectations and Experiences.” (Indianapolis: Strada Education

Foundation, May 2023); “State Opportunity Index,” April 2024.

5

Todd Stottlemyer, “Viewpoint: Every Virginia college student deserves a paid internship,” Washington Business Journal. March 7, 2024. California Learning Aligned Employment

Program (LEAP). (Rancho Cordova, CA: California Student Aid Commission).

HOPE (Hoosier Opportunities & Possibilities Through Education) Agenda. (Indianapolis: Indiana Commission for Higher Education).

stradaeducation.org/nsciMAY 2024 3

Yet despite the growing interest and promising evidence,

there is still a lot we do not know about the internship

experience. Limited data about participation, quality, and

specific design features (e.g., length, pay, nature of tasks,

modality), in addition to concerns about accessibility and

equity, can make evaluating and improving the internship

experience challenging.

6

Targeted research that focuses on

these important issues can help ensure internships and

other work-based learning experiences live up to their

potential and benefit both students and employers in

measurable ways.

To help address these and other questions, the University

of Wisconsin-Madison’s Center for Research on College-

Workforce Transitions developed the National Survey of

College Internships [NSCI) and the Internship Scorecard

to capture metrics for internship structure, quality, and

accessibility.

7

The survey, now administered in partnership

with Strada, examines the reasons students seek internships,

common barriers they face in securing internships, the

overall quality of the experience, and connections to

career goals.

This summary highlights the 2023 NSCI key findings

from third- and fourth-year students attending four-year

institutions. The complete NSCI 2023 findings are available

in the full technical report and also include results from

two-year institutions.

8

6

Matthew T. Hora, Chen Zi, Emily Parrott, and Pa Her. “Problematizing College Internships: Exploring Issues with Access, Program Design,and Developmental Outcomes in

three U.S. Colleges.” [Madison, WI: Center for Education Research, University of Wisconsin-Madison, March 2019). Henrietta O’Connor, and Maxine Bodicoat. “Exploitation or oppor-

tunity? Student perceptions of internships in enhancing employability skills.” British Journal of Sociology of Education 38, no. 4 (2017): 435-449.

7

Hora, et al. “The Internship Scorecard.” (Madison, WI: Center for Research on College Workforce Transitions, University of Wisconsin-Madison, July 2020).

8

Findings are largely consistent across two- and four-year institutions, with the notable exception that overall participation in internships is much lower at two-year institutions.

The sample included third- and fourth-year students from four-year institutions (n=2,824) and students of all class years from two-year institutions (n=2,531).

Data are weighted to be nationally representative by gender, race/ethnicity, class year, and financial aid status.

stradaeducation.org/nsciMAY 2024 4

Key findings from the 2023 NSCI include:

• Nearly every student (96 percent) participating in an internship

sought a way to connect education with career opportunities,

either to gain relevant experience in a specific career (70

percent) or to explore a potential career interest (26 percent).

It appears that students are savvy in seeking ways to

differentiate themselves from peers “without experience”

and/or wanted to discover whether a field of study was a

“good fit” for them.

• Three-quarters (74 percent) of students are extremely or very

satisfied with their internship. Satisfaction is tied to supervisor

support and mentoring, career developmental value, and

opportunities to develop durable skills.

• The vast majority of these internships (more than 75 percent)

were in-person. The median time worked in an internship was

13 weeks.

• The majority of internships occurred in the final year of

college, with juniors about half as likely to have had an

internship in the past year compared to seniors.

• Most students who did not participate in an internship

reported that they wanted to, but could not for a range of

reasons (more than 6 in 10 students at four-year institutions).

Among the biggest obstacles they faced were a lack of time

due to heavy course loads and/or other jobs.

• Financial challenges also impeded students from participating

in internships. About one-third of four-year internships were

unpaid, and even paid internships sometimes require students

to forgo wages or pay for additional transportation and/or

housing.

• Many students reported that they were unsure of how to find

an internship or that there were not sufficient internships

available in their field of study.

Three quarters of students

(74%) were extremely or very

satisfied with their internship.

Less than a quarter of students

(18%) were somewhat satisfied

with their internship.

And 8% experienced little

satisfaction or none at all.

SATISFACTION WITH INTERNSHIP EXPERIENCE

74%

18%

8%

stradaeducation.org/nsciMAY 2024 5

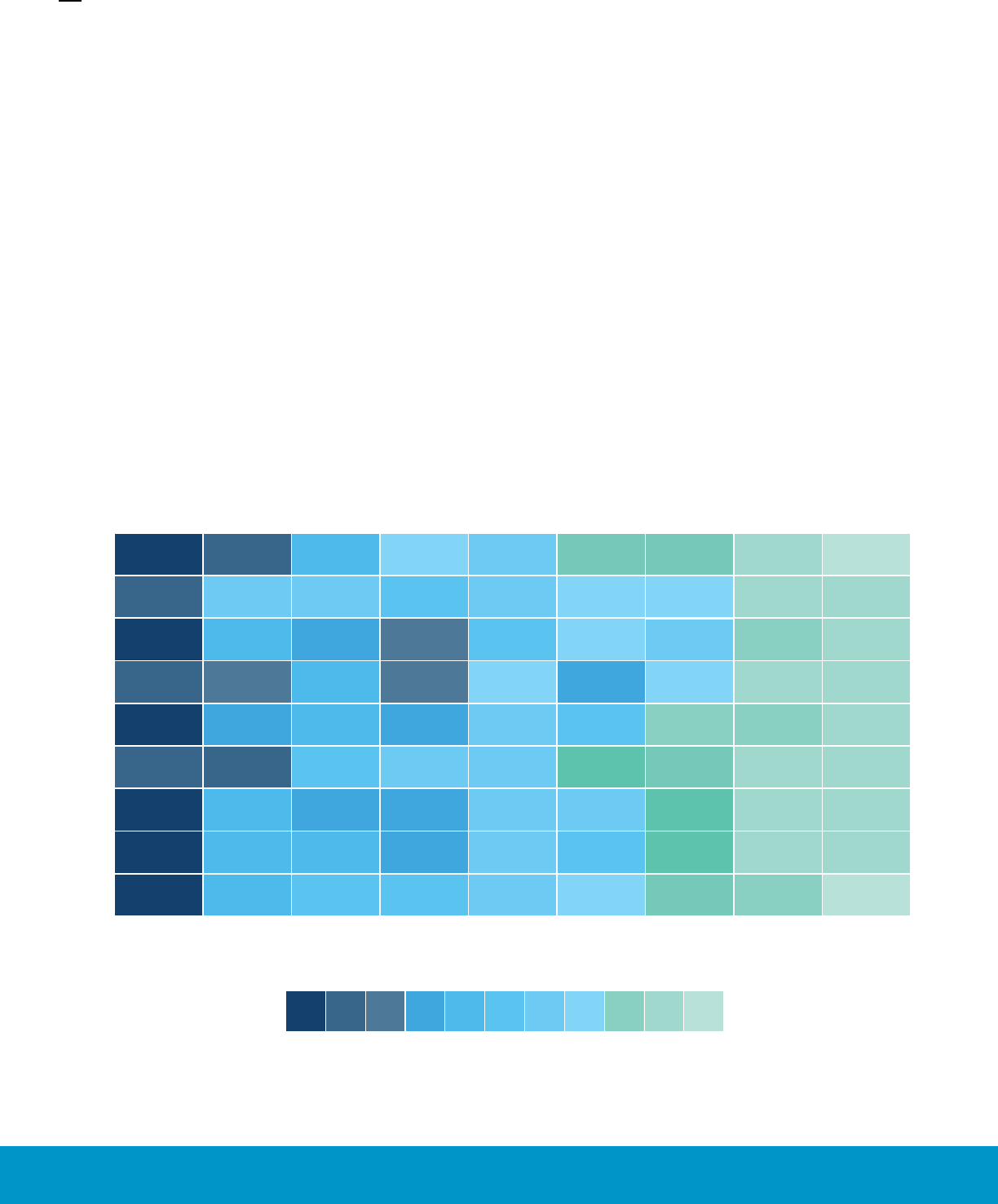

Percentage breakdown of obstacles impacting internship participation by race,

gender, and first-generation status of four-year students

The NSCI also provides a deeper analysis of the common

obstacles facing students who want to participate in an

internship experience. Most of these obstacles were similar

across demographic groups, as seen in the chart below, but

there are a few differences worth noting.

• Male students were less likely to report financial obstacles

such as insufficient pay or needing to work at their current job.

• First-generation college students were more likely to face

financial obstacles.

• Hispanic, Black, and students of another race or ethnicity

were more likely than white or Asian students to identify

transportation as an obstacle.

• Male students and Asian students were more likely than others

to report not being selected for an internship as an obstacle.

65

%

+

1

%

PERCENTAGE KEY

ASIAN

BLACK

HISPANIC

OTHERS

WHITE

MALE

FEMALE

FIRST-GEN

NOT FIRST-GEN

58

%

52

%

65

%

54

%

57

%

51

%

60

%

59

%

57

%

48

%

28

%

32

%

37

%

34

%

48

%

32

%

34

%

38

%

33

%

25

%

35

%

32

%

32

%

29

%

34

%

33

%

32

%

21

%

29

%

38

%

37

%

34

%

25

%

34

%

34

%

30

%

26

%

27

%

30

%

22

%

27

%

27

%

27

%

27

%

27

%

14

%

22

%

23

%

34

%

29

%

17

%

28

%

29

%

22

%

15

%

22

%

26

%

21

%

11

%

14

%

17

%

17

%

15

%

3

%

4

%

5

%

4

%

5

%

4

%

4

%

4

%

5

%

1

%

3

%

3

%

3

%

2

%

2

%

2

%

4

%

1

%

H

eav

y

course loa

d

Applied to

internship but

not selected

Lack of

internships

in field

Work at

current job

Not sure

how to find

internships

Insucient

pay

Lack of

transportation

Internship

canceled

(COVID )

Lack of

childcare

65

%

+

1

%

PERCENTAGE KEY

ASIAN

BLACK

HISPANIC

OTHERS

WHITE

MALE

NON MALE

FIRST-GEN

NOT FIRST-GEN

58

%

52

%

65

%

54

%

57

%

51

%

60

%

59

%

57

%

48

%

28

%

32

%

37

%

34

%

48

%

32

%

34

%

38

%

33

%

25

%

35

%

32

%

32

%

29

%

34

%

33

%

32

%

21

%

29

%

38

%

37

%

34

%

25

%

34

%

34

%

30

%

26

%

27

%

30

%

22

%

27

%

27

%

27

%

27

%

27

%

14

%

22

%

23

%

34

%

29

%

17

%

28

%

29

%

22

%

15

%

22

%

26

%

21

%

11

%

14

%

17

%

17

%

15

%

3

%

4

%

5

%

4

%

5

%

4

%

4

%

4

%

5

%

1

%

3

%

3

%

3

%

2

%

2

%

2

%

4

%

1

%

H

eav

y

course loa

d

Applied to

internship but

not selected

Lack of

internships

in field

Work at

current job

Not sure

how to find

internships

Insucient

pay

Lack of

transportation

Internship

canceled

(COVID )

Lack of

childcare

Demographic Differences in Access

stradaeducation.org/nsciMAY 2024 6

While the potential for internships and other work-based

learning experiences to support students in their journey

from education to employment is clear, educational

institutions, employers, and researchers will need to work

collaboratively to ensure that more students have the ability

to participate in a positive internship experience. To support

those efforts, the NSCI report provides action steps for

increasing access and maximizing the benefits internships

provide to students.

EDUCATORS AND INSTITUTIONAL LEADERS

• Use internships intentionally.

Support students and employers in the development of

structured learning plans and objectives so that students

have clear targets for skill development or other goals they

want to achieve during their internship. Dedicated advisors,

including faculty advisors, could facilitate the development of

these learning plans and assist students with securing aligned

internships.

• Prepare students to secure and thrive in internships.

Provide additional ways for students to engage in career

exploration early in their academic journey in preparation for

an internship. This could include site visits, employer visits to

the classroom, and collaborative projects with employers that

are embedded in coursework.

• Connect internships to other student experiences and

supports.

Integrate and coordinate internships and other experiential

learning experiences across departments on campus to

ensure a more holistic, student-centered approach that

is based on research and uses resources effectively. This

includes intentional collaboration across those entities

that lead career services, service learning, and alumni

engagement.

EMPLOYERS

• Embed internships in your talent strategy.

To overcome the known financial obstacles facing some students,

prioritize investments in paid internships as a means to develop a

more diversified workforce and talent pipeline.

• Have a voice in design.

Engage with colleges and universities to design and scale

industry-specific internships and other learning opportunities

for students.

• Strengthen supervision.

Establish processes and standards for the supervision and

mentorship of interns, including clearly defined roles and

responsibilities for interns and measures of accountability

for supervisors.

RESEARCHERS

• Understand the spectrum of opportunities.

Continue to examine and differentiate the range of internships

and other experiential learning experiences offered to

students, focusing especially on quality, access, and equity.

• Identify the contributions of component parts.

Develop and advance more nuanced definitions and

assessment tools for internships, focusing on both skills and

social capital.

• Examine “best fit” student experiences.

Measure and examine student goals and expectations for

internships (program features, learning goals, student

satisfaction) to better understand what types of internships

are best suited for a range of students.

• Document employer experiences.

Investigate employer perspectives on the value of internships

and other work-based learning models to better understand

employer motivations and identify opportunities for

improvement.

From Research to Action

stradaeducation.org/nsciMAY 2024 7

Principles for Effective Work-Based Learning

Educational institutions, employers, and researchers all

have an important role to play in supporting the policies

and practices that will allow more students to benefit not

only from internships, but also other work-based learning

experiences. While the NSCI findings and recommendations

focus solely on internship, Strada’s research and similar

work done by other experts in the field support a broader

set of principles that can inform programmatic and policy

discussions about the many kinds of work-based learning

experiences.

PAY

Unpaid internships are often out of reach for students who

work part time to pay for their education. The gold standard

is an employer-paid, quality internship or work-based

learning experience that is both affordable and accessible

to a wide range of students. In some internship models,

government entities, education providers, or philanthropic

resources can help offset any additional costs, but any

student-required costs should be kept to a minimum to

maintain accessibility.

CREDIT

Ideally, all internships and work-based learning experiences

should be for credit and/or embedded into a course and

aligned to the student’s major and field of study.

MENTORSHIP AND COACHING

Students should have supervised, human-supported

mentorship and coaching from both the educational

institution and the employer that includes guidance,

feedback, and career planning. At the institutional level, this

might include assigning advisors that help place students in

internships.

SKILLS AND COMPETENCIES

Internships and work-based learning experiences should

provide in-demand, transferable skills and related

disciplinary knowledge that connect to a student’s education

and career goals, as well as their talents and interests. This

means identifying specific disciplinary skills that students

can acquire during the internship and ensuring that these are

incorporated into orientation, mentoring, and everyday work.

EQUITY FOCUS

Internships and work-based learning experiences should

be designed and measured so they are accessible to all

interested individuals, regardless of the financial, logistical,

and systemic barriers they face.

AVAILABILITY

Quality internship and work-based learning opportunities

should be accessible through a range of education, training,

employer, intermediary, and workforce providers and

contexts.

Developing more research-based guidelines for internships

and the broader work-based learning landscape will require

both will and resources, but as the available research shows,

the potential benefits often outweigh the costs. For more

detailed information and research on internships and work-

based learning, please visit www.stradaeducation.org.