CIRCE'S GARDEN: PATTERNS IN LADY LONDONDERRY'S DESIGN AND

MANAGEMENT OF MOUNT STEWART NORTHERN IRELAND 1917-1955

A Report Prepared by

Stephanie N. Bryan, MLA

for

The Royal Oak Foundation,

The National Trust of England, Wales, and Northern Ireland

and Mount Stewart Gardens

2

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I would first like to thank the Royal Oak Foundation for creating this once in a lifetime

opportunity, as well as the Mudge Foundation for generously funding this fellowship. During

my two-month stay in Northern Ireland, I have gained more knowledge about historic landscape

management, garden history, British culture and history, and horticulture than I ever could have

imagined. I look forward to applying a great deal of what I have learned at Mount Stewart to my

future work with historic cultural landscapes in the United States.

It is important to acknowledge the National Trust team at Mount Stewart for their warm

hospitality, insight into the gardens, assistance with various research materials, and patience in

answering my myriad questions. I would like to thank Head Gardener Neil Porteous for sharing

his vast knowledge and experience of Mount Stewart, as well as his infectious energy and

passion for the landscape. Lady Rose and Peter Lauritzen graciously shared their personal

memories of Lady Londonderry and granted me access to the many significant primary resources

that served as a basis for this report. Madge Smart kindly pulled sources from the archives and

provided me space to work from the estate office.

Finally, I would like to thank my mentors and colleagues at the University of Georgia for

helping me cultivate my interests in historic landscape management and garden history. I truly

appreciate Dr. Eric MacDonald and Professor Emeritus Ian J. W. Firth for reading early drafts of

this document and for their encouragement throughout the process.

3

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

The early twentieth-century gardens at Mount Stewart are historically significant because

of their association with Edith, Lady Londonderry, a British aristocrat whose fusion of styles

produced a truly eclectic and idiosyncratic place. The current significance of the gardens,

however, extends beyond its historical associations. For example, in the wake of many global

challenges—climate change, a generation of youth disengaged from nature, energy descent, and

economic downturns—Mount Stewart, similar to other gardens, provides a place where people

can cultivate their relationships with nature and with each other. Thus, it is important for

researchers regularly to reexamine sources, such as Lady Londonderry's original garden books,

that can reveal information about how to manage and interpret the gardens in ways relevant to

the present day.

This report results from extensive research conducted in the Mount Stewart Archives and

aims to guide future management and interpretation of the gardens. Following the executive

summary, the report contains five parts. Part I is an introductory chapter that discusses the

purpose and scope of the report, the research methods and sources, and the nature and character

of Lady Londonderry's garden books. Part II provides an historical overview of Mount Stewart

and explains the evolution and significance of the gardens. Part II concludes by raising the main

research questions regarding what key characteristics originally defined the gardens and what

management

strategies Lady Londonderry and others employed to respond to changing external

circumstances. Parts III and IV address the research questions through a selection of quotes and

data collected from the pages of Lady Londonderry's garden books, among other primary

resources.

4

Part III specifically identifies characteristics of the garden during its peak period from

1917 to 1939. These characteristics include (1) an amalgamation of inspirations and influences,

(2) personalized mythologies and an imaginative sensibility, (3) a range of talents, (4) an exotic

collection, (5) a network of exchange, (6) color, (7) fragrance, (8) season, (9) a labor of love, and

(10) a cultivated exuberance. Part IV outlines seven design and management strategies applied to

the gardens from 1939 to 1955. The following subsections describe these strategies: (1) A

Continuation of Earlier Practices (1939-1940); (2) Responses to Severe Weather Events (1940-

1941); (3) Changes in Purpose I: Vegetables for Consumption (1941-1946); (4) Changes in

Purpose II: Flowers for Market (1941-1946); (5) Seeking Labor Saving Strategies (1947-1955);

(6) Economizing in the Gardens (1947-1955); and (7) Regaining Lost Knowledge (1947-1955).

Finally, Part V concludes with a summary of findings, connects past practices to present goals

and future challenges, and identifies topics for future research.

5

PART I: INTRODUCTION

Purpose and Scope of Research

The purpose of this research is to identify the aesthetic characteristics, design principles,

and adaptive management strategies that defined Lady Londonderry's gardens at Mount Stewart

in Northern Ireland from 1917 to 1955. This information will foremost guide the National Trust

in its future management and interpretation of the gardens. While the National Trust nominated

the gardens during the 1990s as a UNESCO World Heritage Site, the author hopes that new areas

of significance identified and detailed in this report will assist them in the process of designating

Mount Stewart as a place of international esteem.

The history of Mount Stewart dates back to 1744 when Alexander Stewart purchased the

manors of Comber and Newtownards, an extensive landholding that included the Templecrone

demesne (later named Mount Stewart). Throughout the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, the

estate evolved as it passed through several generations of family members who expanded the

house, gardens, and landscape park. It was not until 1915 that Lady Londonderry's husband,

Charles Stewart Henry, inherited the property and succeeded to the title of 7th Marques. Lady

Londonderry began creating the gardens around 1917 and developed them with much expense

and passion over a span of nearly forty years. As Lady Londonderry aged, the National Trust

assumed management of the gardens in 1955.

The scope of this research is thus limited to the period from 1917-1955 when Lady

Londonderry created and managed the gardens that survive today. Although she remained

heavily involved in the gardens until her death in 1959, the author has not included this brief

transition period in the report because the National Trust inevitably would have influenced Lady

Londonderry's actions and decisions. During Lady Londonderry's period at Mount Stewart, she

also created and maintained gardens at Kinloch, a shooting lodge in Sutherland where she

6

periodically resided. Because of time constraints, the author was unable to research this garden

and determine whether Lady Londonderry might have applied design principles and management

strategies similar to Mount Stewart.

Research for this report focused almost entirely on primary documents contained in the

Mount Stewart Archives. The author concentrated on Lady Londonderry's nine garden books

because no one has thoroughly analyzed the sources as a complete entity. The author also

reviewed the National Trust's 2011 "Conservation Management Plan" to understand the

significance of the gardens, the management philosophy applied by the National Trust, and

challenges presently facing management. While the National Trust has managed the gardens for

over fifty years, the author did not attempt to review the extensive period from 1959 through the

present to gain a full understanding of how the gardens have evolved into their current state since

Lady Londonderry's tenure.

Research Methods and Sources:

The author used a variety of research methods and sources to compose this report.

Primary sources, such as garden books and published articles by Lady Londonderry, provided

great insight into her thought process, and revealed how she managed the gardens over a course

of nearly forty years. Additionally, the author reviewed literature that comprised Lady

Londonderry's library collection, specifically Arthur T. Bolton's Gardens of Italy and various

books of the Arts and Crafts Movement. Many of these books contained markers, loose sketches,

and notations by Lady Londonderry and thus served as one of her fundamental sources of

inspiration.

7

Historic photographs complemented the aforementioned textual resources by offering a

rich visual record of the gardens before World War I. Unfortunately, no photographs have been

identified for the critical twenty-year period from the start of World War II in 1939 to the time

when the National Trust acquired the gardens in 1955. This gap in photographic documentation

forced the author to rely solely on written accounts to understand how the gardens may have

changed. It is difficult to determine why there are no images from this period and one might

question whether this was an intentional choice, or caused by some unknown external

circumstance. Lady Londonderry's youngest daughter, Lady Mairi, reportedly captured the

gardens on cine film during the 1950s. While these moving pictures would certainly help fill this

gap in visual data, the author was unable to examine them because they remain in an obsolete

viewing format.

A range of secondary resources also supplemented this research, including the following:

(1) Circe: The Life of Edith, Marchioness of Londonderry by Anne de Courcy provided a useful

biographical account, yet surprisingly contained little mention of the Mount Stewart gardens; (2)

Anne Casement's unpublished report "Mount Stewart Garden Archives and Historical Survey

1917-1959" inventoried the plethora of primary resources at hand and included practical

chronologies of the estate and its garden features, significant persons associated with the

gardens, acquisition of plants, and so forth; (3) pamphlets published by the National Trust and

intended to aid the visitor's experience supplied a combination of basic historical information and

plant references; (4) the "Mount Stewart Garden Conservation Management Plan 2011" was an

indispensible resource that outlines the context and significance of the gardens, and states the

management philosophy currently employed by the National Trust; and, finally, (5) several

8

unpublished articles about the gardens, such as Michael J. Tooley's "Gertrude Jekyll and Mount

Stewart" afforded detailed analyses regarding focused topics on the garden's history.

Interviews with key persons associated with the gardens proved to be an invaluable

source. Lady Rose kindly shared personal recollections of her grandmother, Lady Londonderry,

as well as her experience of growing up on the estate. Members of the National Trust

management team, particularly Neil Porteous, Head Gardener, also contributed a wealth of

historical and practical knowledge about the gardens and greater region around Strangford

Lough. Additionally, informal conversations with visitors revealed much about how the public

currently uses and interprets the gardens. Finally, the garden itself proved to be one of the richest

resources, enabling the author to compare various recorded and verbal accounts with firsthand

observations.

The Nature and Character of Lady Londonderry's Garden Books

For this report, the author meticulously reviewed Lady Londonderry's nine garden books.

A careful analysis of the nature and character of these books revealed what types of questions

they can and cannot answer. Although garden historian Anne Casement categorized Lady

Londonderry's garden books as "diaries,"

1

the author considers this term misleading. A diary

connotes a personal account and usually one that offers insight into the writer's emotions or

values. Moreover, a person usually maintains a diary on a daily or weekly basis, as events spur

thoughts and feelings. Because Lady Londonderry's garden books do not contain any personal

accounts of her feelings or emotions towards the gardens, the author has avoided using the term

diary. Instead, the garden books generally fit within three categories: (1) record books, mostly

containing plant orders, instructions, or documentation of design work; (2) scrapbooks,

1

Anne Casement, "Mount Stewart Garden Archives and Historical Survey 1917-1969 Part 2," (1999), 93.

9

predominantly comprised of article clippings, photographs, letters, and random notes; and (3) a

combination of the two. See Appendix A for a detailed description of each garden book.

It is certainly useful that Lady Londonderry kept thorough records of the plants she

procured, including quantities, prices, sources, varieties, and so forth. Unfortunately, it is

difficult to infer anything about the values, events, motives, or other factors that spurred the

actions documented by these statistics. While the garden books contain much correspondence,

these documents also offer little personal insight because acquaintances wrote them to Lady

Londonderry and therefore only provide one side of the conversation. The author recommends

that a future researcher review the personal diaries kept by Lady Londonderry to determine

whether they offer insight into how she experienced and felt about her gardens (e.g., whether she

predominantly viewed the gardens as a showpiece to her elite circle of friends or if they fulfilled

some sort of deeper emotional need in her life).

Despite containing copious notes on plants, Lady Londonderry's garden books thus offer

a fragmentary view of how the gardens developed and evolved as a whole entity. Moreover,

because their content rarely flows in a consistent or sequential order, it often is difficult to piece

together a coherent narrative. The disorganized nature of Lady Londonderry's garden books

lends insight into her thought process and suggests that she did not think in a linear fashion. The

ways Lady Londonderry experimented with her gardens through plant material and allowed the

spaces to evolve organically without a definitive set of plans reflects this nonlinear aspect of her

personality.

Behind the front covers, many of the garden books contain indices that Lady

Londonderry later added. The subsequent inclusion of these indices further confirms the

disorganization of these garden books because it suggests that Lady Londonderry probably

10

needed the indices to facilitate finding information relating to specific topics. The indices also

signify that Lady Londonderry relied on these sources as references during the years after she

created them. Likewise, it is only appropriate that we, too, should consistently rely on them to

guide us in future management despite their shortcomings.

11

PART II: OVERVIEW OF THE HISTORY, EVOLUTION, AND SIGNIFICANCE

OF THE GARDENS AT MOUNT STEWART

Overview of the Gardens during Lady Londonderry's Tenure

When she later recalled visiting the grounds and house at Mount Stewart during the

1910s, Edith, 7th Marchioness of Londonderry, described the estate as "the dampest, darkest, and

saddest place I had ever stayed in, in the winter. Large Ilex trees almost touched the house in

some places and sundry other big trees blocked out all light and air."

2

While the grounds at

Mount Stewart left a dismal impression on Lady Londonderry, a 1913 account by her mother-in-

law Theresa, 6th Marchioness of Londonderry, described a different experience of the place. In

"The Garden at Mount Stewart," Theresa wrote: "In January when we gain the shelter of the

drive, the brilliant green of the grisileas and the grey green ilexes give a sense of warmth and

comfort ... Snowdrops all planted round the stems of the trees and the deciduous trees look like

ghosts mixing with the evergreens and the dark glossy leaves of the rhododendrons, with here

and there a patch of brilliant colour, the early flowering scarlet which never fails to show buds

and flowers in early January."

3

In 1915, only two years after Theresa wrote about the gardens, her son Charles Stewart

Henry, the 7th Marques of Londonderry succeeded to the title and inherited the family estate.

During this World War I period, Charles and his wife Edith frequently visited Mount Stewart,

which served as a convalescent hospital for soldiers. It was not until 1921, however, when

Charles became the Minister for Education in the first Ulster Parliament that he and Edith chose

Mount Stewart as their permanent residence. Because the gardens at Mount Stewart suffered

neglect during WWI or whether the designs were not of her taste, Lady Londonderry employed

2

Edith Marchioness of Londonderry, "Foreword to the Mount Stewart Garden Guide Book," (1956).

3

For the complete transcribed account, see Anne Casement, "Mount Stewart Garden Archives and Historical Survey

1917-1959 Part One," 13-15.

12

soldiers left jobless after the war to "make the grounds surrounding the house not only more

cheerful and livable, but beautiful as well."

4

Two key occurrences that shaped Lady Londonderry's life may have instigated this act of

renovation. Lady Londonderry became increasingly independent as Lord Londonderry,

consumed by both political and personal affairs, remained largely absent from their marriage.

Secondly, during WWI, Lady Londonderry established and managed a volunteer force

comprised of tens of thousands of women, known as the Women's Legion. This experience gave

Lady Londonderry the confidence and organizational skills necessary to overseeing large-scale

projects, such as creating a garden.

5

As a member of the aristocracy, Lady Londonderry had long

proven herself as a driving force in British society, and the gardens at Mount Stewart became a

new vehicle for her to express her power and energy.

Taking advantage of the microclimate

6

that produced relatively mild weather along the

nearby Strangford Lough, Lady Londonderry and her head gardener, Thomas Bolas, successfully

cultivated tender plants they obtained predominantly from North American, Asiatic, and

southern hemispheric regions. Few gardeners attempted to grow such non-native species

elsewhere in the United Kingdom because the tender plants rarely survived the region's colder

winters. Because of the microclimate, Mount Stewart infrequently experienced the hard frosts

that normally would harm tender plants.

4

Londonderry, "Foreword to the Mount Stewart Garden Guide Book."

5

Casement, "Mount Stewart Garden Archives and Historical Survey 1917-1959 Part One," 17.

6

In 1957, Lady Londonderry described these climatic conditions: "...we are situated on the southern shore of the

narrow peninsula of the Ards... The House faces almost due south and is but a stone's throw away from the salt

water Lough Strangford... The eastern shore of the Ards is on the Irish Sea and Belfast Lough sweeps right round

the northern shorefar inland. So narrow is the space between the head of Strangford Lough and that of Belfast

Lough that Mount Stewart... experiences island conditions. The climate is sub-tropical ... in hot weather we always

have extremely heavy dews at night. We do not have an excessive rainfall... we get all the sun of the east coast with

its drier conditions... the Gulf Stream running up the Irish Sea washes the shores all round the promontory."

Londonderry, "Foreword to the Mount Stewart Garden Guide Book."

13

A letter dated 4 June 1929 by Mrs. R. S. Milford from The Nurseries in Chedworth

offers some insight into this situation. She exclaimed, "It is heart-breaking to read of all the

things that can be grown in Ireland—which we struggle to keep alive in this chilly spot!"

7

A

letter dated 13 May 1936 from the National Botanic Gardens in Cape Town, South Africa offers

another reaction. Director R. H. Compton wrote, "I have much pleasure in sending seeds of

Psoralea pinnata herewith ... It was interesting to hear how well this charming shrub grows in

Northern Ireland."

8

An embankment known as the Sea Plantation, which existed between Strangford Lough

and the southern edge of Mount Stewart, also enabled Lady Londonderry to grow tender plants at

Mount Stewart. This feature protected the gardens from strong winds and salt waters that

originated from the lough. Lady Londonderry further sheltered her gardens by enhancing a

buffer of trees that grew along the southern border of the property. These unique geographic and

topographic features created a situation where many plants at Mount Stewart thrived and reached

record proportions in relatively short periods.

During the 1920s and 1930s, Lady Londonderry honed her horticultural skills through

self-education and experimentation, and her confidence as a gardener swelled. The gardening

successes at Mount Stewart undoubtedly added to a growing sense of awe and delight among

Lady Londonderry's circle of family and friends, in addition to those who read romanticized

accounts of the gardens in publications such as Country Life or Home and Gardens. A letter from

her gardening mentor, Sir Herbert Maxwell, dated 4 September 1933, confirmed this response,

stating, "You certainly fulfill the role of enchantress in all that you touch..." By the 1950s, after

only several decades had passed, the garden often deceived visitors by its centuries-old

7

Edith Marchioness of Londonderry, "Mount Stewart Gardens 1927-1936," (1927-1936), 36.

8

Edith Marchioness of Londonderry, "Mount Stewart Gardens 1935," (1935).

14

appearance. In his article entitled "Rhododendrons at Mount Stewart," Frank Kingdon-Ward

explained "In this favoured spot they grow faster than they do anywhere else, thus making

nonsense of the collector's reports of their size in the field."

9

Lady Londonderry was part of a significant movement in the history of horticulture and

gardening. Her subscriptions to foreign plant expeditions led to many new discoveries. A vast

network of exchange among gardeners, horticulturalists, botanists, explorers, and plant collectors

largely characterized this period in horticulture and gardening. Individuals from across the world

shared and traded innumerable seeds and cuttings with each other through the mail.

Consequently, the gardens at Mount Stewart housed one of the most unusual and diverse private

plant collections in the British Isles.

Significance of the Gardens Today

The National Trust considers Lady Londonderry's tenure from 1915 to 1959 to be Mount

Stewart's most significant historical period. On its website, the National Trust succinctly explains

that "Mount Stewart Gardens, by virtue of their creators, horticulture, plant collection, design

and microclimate, are established as

an unrivalled example of 20th-Century gardening...."

10

The

2011 Conservation Management Plan provides a more detailed statement of significance, a

portion of which reads as follows:

"... The garden is one of the few late compartmentalised Arts and Crafts-like

gardens. Mount Stewart is one of the great 20thC “personalised” gardens such as

Hidcote and Nymans, which combined a strong artistic theme with an unrivalled

plant collection. The basic arrangement is similar: artistically planted formal

compartmentalised gardens around the house, surrounded by a more natural

woodland garden with semi-natural planting. But Mount Stewart stands apart in

Lady Londonderry’s use of sculpture and mythology. Sculptures representing the

9

Edith Marchioness of Londonderry, "Mount Stewart Gardens 1937," (1937), 215.

10

National Trust, "The Garden Conservation Plan for Mount Stewart," National Trust,

http://www.nationaltrust.org.uk/home/view-page/item427360/264045/.

15

members of the Ark Club- founded by Lady Londonderry during the First World

War- populate the garden. Lady Londonderry was an early proponent of the use of

cast concrete by local craftsmen to create structure & form in the garden.

Of the great plantsman’s gardens from the early twentieth century such as Crarae,

Inverewe, Bodnant, Rowallane—none combined their collections with such

artistry of design, experimentation in their planting, or achieve such a romantic

and spiritual effect. The plant collection established at Mount Stewart (when in its

prime) was unique in the British Isles, and may only have been eclipsed by that of

Tresco Abbey Garden on the Isle of Scilly. Mount Stewart garden is of great

significance, locally within Northern Ireland, nationally and internationally. ... "

11

Aside from historical significance, the National Trust recognizes that many of its

protected sites are crucial to examining current global challenges of both nature and culture. The

National Trust explains that "helped by the unique microclimate on the Ards Peninsula, Mount

Stewart manages the largest plant collection in the National Trust's ownership."

12

Consequently,

the gardens at Mount Stewart are "proving to be a valuable haven for some rare plants threatened

by climate change in their native habitats."

13

In his 1984 "Woody Plant Catalogue for Mount Stewart," Michael Lear claimed Mount

Stewart's present collection of Southern Hemisphere plants as its most notable botanical asset.

The mild climate at Mount Stewart permits a greater range of "species plants" to survive.

Consequently, Lady Londonderry was less interested in filling her collection with cultivars and

hybrids. The staff at Mount Stewart recently identified in its collection a shrub known as

Brachyglottis brunonis (Senecio centropapus), which has become rare in its native Tasmanian

habitat.

14

The National Trust secured cuttings for its Plant Conservation Centre in Devon with

11

Neil Porteous, Mike Buffin, and Phil Rollinson, "Mount Stewart Garden Conservation Management Plan 2011,"

(2011), 25.

12

National Trust, "Setting the Example of Sustainability," National Trust, http://www.nationaltrust.org.uk/mount-

stewart/our-work/.

13

Ibid.

14

National Trust, "Survey at Mount Stewart Expose Important Plants," Nationanl Trust,

http://www.nationaltrust.org.uk/what-we-do/what-we-protect/gardens-and-parks/projects/view-page/item808960/.

16

the intent that propagation "will ensure the survival of this rare specimen at Mount Stewart and

in other gardens for decades to come."

15

Collectively, the National Trust's sites serve as "sensitive barometers registering the

pressure of environmental change on our lives, and on the natural world around us."

16

Thus, they

are significant places where researchers can examine solutions and ways to adapt to these events.

The National Trust is "keen to find ways of reducing the environmental impact of gardening" and

aims for their sites to serve as models for the community.

17

For example, Mount Stewart

recently installed a new biomass boiler, which efficiently burns locally sourced wood chips to

provide heat and hot water to the vast estate. The staff has also reduced their consumption of

fossil fuels by adopting "an energy-efficient approach to the working day."

18

As natural resources have dwindled in the twenty-first century, so has youth engagement

with nature.

19

Gardens like Mount Stewart are invaluable to the community because they provide

places where children can cultivate relationships with nature and with each other, and lead

healthier lives into their adulthood.

20

Additionally, such places provide a major source of tourism

in Great Britain and are significant to sustaining local economies.

21

15

Ibid.

16

National Trust, "Space to Grow: Why People Need Gardens," (2012), 14.

17

Ibid.

18

National Trust, "The Warmth from the Willow," National Trust, http://www.nationaltrust.org.uk/home/view-

page/item401315/264045/.

19

An Independent Research Study for the National Trust released during July 2010 suggests that "Children are

spending 60 percent less time in nature than their parents did at the same age." National Trust, "Our Land, For Ever,

For Everyone," (2012), 9.

20

National Trust, "Saves Children's Relationship with the Outdoors," National Trust,

http://www.nationaltrust.org.uk/what-we-do/news/view-page/item788564/. Stephen Moss, "Natural Childhood,"

(National Trust, 2012).

21

National Trust, "Space to Grow: Why People Need Gardens," 4.

17

Research Questions

Today, the National Trust faces new challenges in sustaining the internationally

significant gardens at Mount Stewart in the wake of global climate change, a generation of youth

disengaged from nature, energy descent, and economic downturns, among other events that

remain unforeseen. Undoubtedly, parallels exist between past challenges and present ones. For

example, the Interwar Period of reabsorbing jobless soldiers into industry is not very different

from the National Trust's recent endeavor to initiate a volunteer program that offers temporary

relief to unemployed individuals, particularly from the housing sector. While the volunteer

program provides a short-term solution to the management of a place that has remained

dependent on large numbers of employees and volunteers, it is important to consider a long-term

outlook so that management can adapt when circumstances change.

This report addresses the following questions: What characteristics defined the gardens at

Mount Stewart during their peak period from 1917-1939? How did Lady Londonderry adapt her

original designs to suit changing needs during WWII? After WWII, how did Lady Londonderry

attempt to revitalize her gardens before she transferred ownership to the National Trust? Finally,

what insight for future management can be gleaned from the aesthetic characteristics, design

principles, and adaptive management strategies applied to the gardens from 1917-1955? The

knowledge gained from answering these questions will guide long-term management and

interpretation of the gardens. This will ultimately assist the National Trust in fulfilling its

mission of keeping alive "the Londonderry sprit"

22

while concurrently maintaining the gardens as

a powerful source of discovery and delight "for ever and for everyone."

23

22

Porteous, Buffin, and Rollinson, "Mount Stewart Garden Conservation Management Plan 2011," 27.

23

National Trust, "For ever, For everyone Appeal," National Trust, http://www.nationaltrust.org.uk/get-

involved/donate/current-appeals/for-ever-for-everyone-appeal/.

18

Fig. 1 (above) shows a 1956 plan of the Mount Stewart Gardens, modified by Lady Mauri Bury. The plan shows the various

compartmentalized spaces , such as the following: (3) the Mairi Garden; (4) the Dodo Terrace; (5) the Italian Garden; (6) the

Spanish Garden; (8) the Rock Garden; (9) the Shamrock Garden; and (10) the Sunk Garden. Several circulation routes comprise

transitional spaces , such as (7) the Lily Wood, (12) the Lake Walk; and (15) the Rock Walk, (16) the Ladies Walk, and (16a) the

Woodland Walk. Source: Guide to the Gardens published by the National Trust.

19

Part III: AESTHETIC CHARACTERISTICS AND DESIGN PRINCIPLES

Introduction

Lady Londonderry's garden books and correspondence reveal many qualities that

fundamentally defined the gardens at Mount Stewart as they reached their pinnacle during the

mid- to late-1930s. Since the gardens mostly were laid out and first achieved fame from 1917

through 1939, a full understanding of their historic characteristics requires a close examination of

that period.

24

This section of the report identifies important aspects of the gardens, which are

grouped into four headings. The first section titled Sources of Ideas describes (1A) an

amalgamation of inspirations and influences, (1B) personalized mythologies and an imaginative

sensibility, and (1C) a range of talents involved in creating the gardens. The second section

categorized as Plant Selections and Introductions details Lady Londonderry's (2A) exotic

collection of plants and her (2B) network of exchange. The third section explains the Plant

Arrangements at Mount Stewart, including (3A) color, (3B) fragrance, and (3C) season. The

fourth and final section discusses Labor Intensive Practices through Lady Londonderry's (4A)

labor of love and (4B) cultivated exuberance.

1) Sources of Ideas

1A) An Amalgamation of Inspirations and Influences:

In developing the gardens at Mount Stewart, Lady Londonderry referenced many and

varied sources. She drew inspiration from prevailing gardening practices, fond childhood

memories, travels, literature, and popular publications, among others. As Lady Londonderry

24

The purpose of the information contained in the subsequent sections is to provide a basis for understanding and

evaluating the significance of changes that occurred in the gardens during and after the Second World War. The

characteristics identified are by no means an exhaustive list and certainly many other qualities exist. In addition,

some of the characteristics warrant further investigation because they are only briefly described within the report.

20

assimilated these diverse interests into her gardens, she created a highly personalized place that

she could enjoy with her family and friends.

Lady Londonderry's Mediterranean travels, coupled with her well-read copy of the

Arthur Thomas Bolton's The Gardens of Italy, infused a strong Italian influence into her designs.

For example, her plans for an orangery greatly resembled the layout of the Medici Villa Castello

with its many potted fruit trees (Figs. 2-3). Terracotta pots filled with orange trees adorned

various garden spaces at Mount Stewart and as Lady Londonderry suggested, "On warm

evenings their delicious scent almost reminds one of Italy."

25

In her garden book, she explicitly

stated that the "idea [for the Italian Garden was] taken from gardens of Italy—Villa Gambaraia

(Florence) and adapted to site—also Villa Caprarola."

26

She also wrote that the "rose garden

design and lower terrace [was] designed by myself—but after the style of one of the formal

gardens of Dunrobin," her childhood home in Scotland. Adding to the mixture of influences, she

further explained, "The gateway out of garden ... [was] taken partly from the gateway at Easton

Neston, Northamptonshire."

27

In addition to Italian influences and fond memories, Lady Londonderry drew upon

contemporary practices in British gardening, such as through the Arts and Crafts Movement. The

library collection in her sitting room included numerous Arts and Crafts publications, many of

which contain Lady Londonderry's place markers, notations, and sketches.

28

Lady Londonderry

25

Edith Marchioness of Londonderry, "The Gardens at Mount Stewart," Journal of the Royal Horticultural Society

LX, no. 12 (1935): 522.

26

Edith Marchioness of Londonderry, "Mount Stewart Garden Book No. 1 1922-1927," (1922-1927), 5.

27

Ibid.

28

This collection includes the following books: Garden Architecture by Geoffrey T. Henslow (Dean and Son,

London 1926); Wall and Water Gardens by Gertrude Jekyll; three copies of Garden Ornament by Gertrude Jekyll

and Christopher Hussey (Country Life, 1918); Gardens for Small Country Houses by Gertrude Jekyll and Sir

Lawrence Weaver (Country Life, London, sixth edition, 1927); Art and Craft of Garden Making by T.H. and E.P.

Mawson (Batsford, London, fifth edition, 1926); and so forth. Casement, "Mount Stewart Garden Archives and

Historical Survey 1917-1969 Part 2," 245-51.

21

Fig. 2 (above) shows Lady Londonderry's plan for an orangery in the Walled Garden. Her

writing above the plan indicates "Page 281 Gardens of Italy" inspired it. Source: Londonerry,

Edith, Marchioness of. "Mount Stewart Garden Book No. 2 1922-1927,"7.

Fig. 3 (below) shows the referenced image of Villa Castello. Lady Londonderry's plan bears

much resemblance in the quadripartite division of space, the rectangular beds contained within

each section, and the many potted plants lining the paths. Source: Bolton, Arthur T. Gardens of

Italy. England: Country Life Limited, 1919.

22

owned three copies of Garden Ornament written by Gertrude Jekyll and Christopher Hussey,

which implies that she highly valued this particular work. The gardens at Mount Stewart contain

most types of garden ornaments illustrated within the text, such as gates, seats, stairways, pools,

terraces, and courts.

Although the library collection at Mount Stewart confirms that Gertrude Jekyll's ideas

and theories greatly influenced Lady Londonderry, correspondence and historic photographs

suggest that she did not always follow Jekyll's personal advice. For example, in a letter to Lady

Londonderry dated 19 December 1925, Jekyll wrote,

"Many thanks for so kindly letting me see the photographs of the Mount Stewart

gardens ... The garden seems to have grown up well ... Looking at the photograph

of the house front with the large flight of steps it looks as if the house ought to be

relieved of the thick growth of Ivy that smothers the pediment and top of the

portico and in fact the whole projection. That facade wants these architectural

features unobscured, and to have the natural light and shade of all the part that

stands out as intended by the architect. ... I know you will let me make these

remarks..."

Historic photographs from the 1930s reveal that for many years Lady Londonderry instead

maintained a heavy cover of vines on the south facade of the house (Figs. 5-6).

Aside from correspondence, it is difficult to determine whether Jekyll played a role in

any of the planting schemes at Mount Stewart. In 1920, when the gardens were still in their early

stages, Jekyll produced a series of plans for the West Garden, the terrace between the West

Garden and the house, and the Italian Garden.

29

It is uncertain to what extent Lady Londonderry

29

Michael Tooley suggests "a comparison of the planting plans for the walls of the Sunk Garden with the plants that

were growing there in August 1983 and the metal labels that have survived in situ from the 1920s shows that for the

walls, at least, Gertrude Jekyll's planting plans were realised." For more detailed information regarding Tooley's

analysis and theories regarding the Jekyll-Londonderry connection, refer to his unpublished paper: Michael J.

Tooley, "Gertrude Jekyll and Mount Stewart."

23

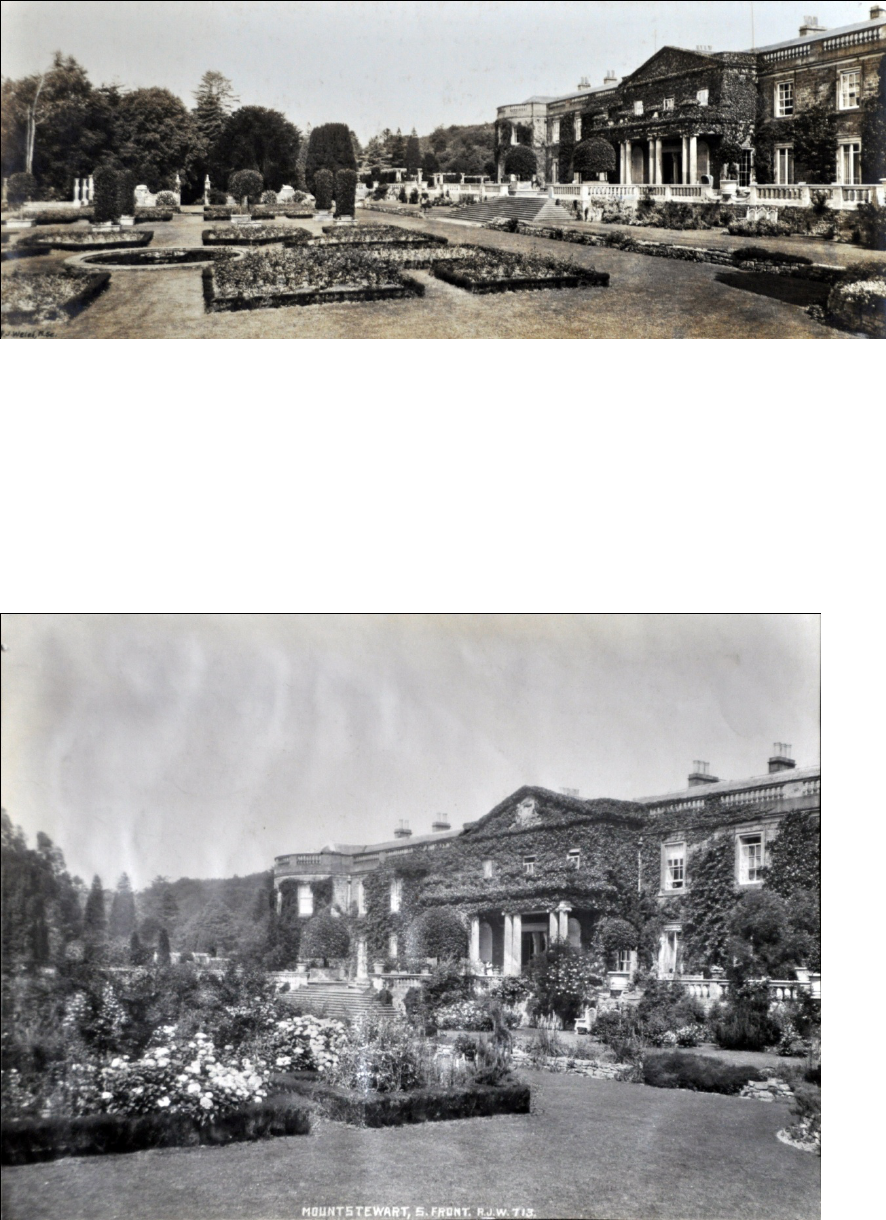

Fig. 5 (above) shows thick ivy on the south facade of the house in 1925, around the same time

when Jekyll wrote to Lady Londonderry. Source: Mount Stewart Archives.

Fig. 6 (below) shows an image of the house by R. J. Welch in the 1930s captured from a similar

angle. Both pictures reveal a thick cover of ivy maintained on the facade, with columns and

windows remaining exposed. Source: Mount Stewart Archives.

24

may have had input into Jekyll's layout and plant selections. Furthermore, it is hard to determine

whether Lady Londonderry ever fully or partially implemented the designs. For example, some

of Lady Londonderry's planting records for the West Garden correspond to plants on Jekyll's list,

such as veronicas and delphiniums. Lady Londonderry's notes, however, infrequently indicate

where she specifically placed plants and most often suggest only a general location within the

gardens. Her records also imply that her planting plans varied from year to year. Lady

Londonderry wrote that in 1921 "antirrhinums - cherry red - [West Garden] beds first

completed."

30

In 1922, she stated, "Anchusa and Delphiniums - from Whiteless - very

successful" and by autumn of the same year, she suggested to "Replant beds - using Dahlias ...

Gladiola padavennis and Primulinus mixed 1000 Liliums - candidum - superbum and

pardalinum - 500 Hyacinthus candicans - 48 Aconitum wilsoni and fischeri."

31

The correspondence confirms, however, that Lady Londonderry purchased plants from

Jekyll and that she visited Jekyll’s garden at her home, Munstead Wood. In a letter dated 9

November 1927, Jekyll wrote, "That good undershrub that you saw here, that makes good cover

(and food) for game, is Gaultheria shallon. I could send you almost any quantity. ... I am so glad

to know that the plants from here are doing well." While this correspondence does not offer any

insight into the personal relationship between Jekyll and Lady Londonderry, it at least verifies

they maintained a limited business relationship.

In addition to Arts and Crafts influences, Lady Londonderry called upon her Scottish

heritage and upbringing to entwine themes from Celtic folklore into her gardens. For example,

she delineated the Shamrock Garden with a trifoliate enclosure of clipped hedges (Fig. 7). Atop

30

Londonderry, "Mount Stewart Garden Book No. 1 1922-1927," 25.

31

Ibid.

25

Fig. 7 shows an image by R.J. Welch of the hand-shaped planting bed, which Lady Londonderry

would have appropriately filled with red flowered plants. Source: Mount Stewart Archives.

the hedges, topiaries depicted "a complete hunting scene supposed to represent the family of

Stewart arriving for the chase...The figures...were taken from Mary 1st of England's Book of

Hours."

32

The main feature inside the Shamrock Garden, however, was a "large bed [that

formed] ... the left hand, the bloody hand of the McDonnell's, the direct ancestors of Frances

Anne, Marchioness of Londonderry."

3334

32

Londonderry, "The Gardens at Mount Stewart."

33

Londonderry, "Mount Stewart Garden Book No. 1 1922-1927," 40.

34

The story relates to when two rival Scottish clans raced from Scotland to Ireland, in the hopes of whoever touched

Ireland first would possess the land. As McDonnell saw that he was losing the race, he cut off his left hand, threw it

on the shore, and claimed the land.

26

Celtic themes are evident elsewhere in the gardens, such as in the family burial grounds

which Lady Londonderry aptly named Tir N'a nOg—or land of the forever young—and a nearby

sculpture of the white stag, who, according to legend, accompanied spirits to Tir N'a nOg.

35

Lady

Londonderry's garden books show a preoccupation with these themes, and she often saved

articles on topics such as legends and superstitions in the garden.

36

Additionally, she collected

books such as Ella Young's Celtic Wonder Tales and even composed her own manuscript

entitled Character and Tradition. While many gardens contain Celtic themes, Classical

architecture, or Arts and Crafts ornaments, the amalgamation of these influences distinguishes

the gardens at Mount Stewart.

1B) Personalized Mythologies and an Imaginative Sensibility:

Lady Londonderry worked in a long-standing European tradition in which designers

wove Classical mythology into garden layout, architecture, and ornament. Similar to other

garden designers, Lady Londonderry selected deities and mythologies from the Classical canon

as a means to comment on her own personality, life history, accomplishments, values, and

politics. Lady Londonderry's practice of selectively incorporating Classical mythology was not

unique; however, the result of a garden with mythological elements as biographical commentary

on its owner and author is necessarily idiosyncratic and individual.

Some time during 1915, shortly after moving to Mount Stewart, Lady Londonderry and

her circle of family and friends known as the "Ark" began to hold weekly meetings over dinner.

This ritual offered the members a much-needed reprieve from wartime work and soon became an

35

Porteous, Buffin, and Rollinson, "Mount Stewart Garden Conservation Management Plan 2011," 26.

36

Londonderry, "Mount Stewart Gardens 1927-1936," 124-25.

27

outlet for fun. Although membership in the Ark was by invitation only, the club quickly grew to

include an eclectic mix of personalities ranging from poets to politicians.

Members were required to adopt the name of a real or mythological creature, and Edith

identified herself with "Circe," the alluring sorceress from Greek mythology.

37

By 1924, Lady

Londonderry had commemorated certain members through cast-concrete sculptures of their

chosen characters that she placed throughout the gardens. She likely derived the forms for these

pieces likely from illustrations in Queen Mary's Psalter, a religious book that held special

significance to Lady Londonderry. The book also inspired the topiaries surrounding the

Shamrock Garden.

38

Lady Londonderry conceived the Dodo Terrace to display many of these

sculptures and drew inspiration for the terrace architecture from the Boboli Gardens in Florence

(Figs. 8-10).

Lady Londonderry also derived the structure and organization of the herm statues in the

Italian Garden at Mount Stewart from Italian influences, particularly the Upper Garden of the

Villa Farnese at Caprarola. Lady Londonderry selected imagery for the herms to reflect her

persona of Circe.

39

The herms sequentially portrayed scenes from Homer's Odyssey in which

Circe used magic potions to transform her enemies into swine (Figs. 11-13). For example, the

first herm shows a man's face flanked by clusters of grapes and swine's legs. On the second

herm, the face changes shape while a pair of hands grasps a cup presumably filled with Circe's

potion. Finally, the third herm depicts a fully transformed, devilish swine-like face with four

37

Anne de Courcy, Circe, The Life of Edith, Marchioness of Londonderry (Great Britain: Sinclair-Stevenson,

1992).

38

Lady Londonderry obtained a copy of this during Christmas 1912 from her mother. The volume contains various

notations and marks by Lady Londonderry and the illustrations more than likely inspired the ark and several of the

animal sculptures.

39

Lady Londonderry seems to have truly identified with this character. Correspondents, such as Lord Charles

Dunleath, who wrote personal letters to Lady Londonderry about gardening matters, often addressed her as "My

dear Circe."

28

Fig. 8 (above left) shows an undated conceptual sketch for the Dodo Terrace by Lady

Londonderry architecturally inspired by the balustrade of the Isolotto from the Boboli Gardens in

Florence (Fig. 9, above right). Sources: Sketch found as a bookmark in Lady Londonderry's

copy of Gardens of Italy 1919 Country Life publication. Source: Bolton, Arthur T. Gardens of

Italy, 271. England: Country Life Limited, 1919.

Fig.10 (below) depicts the completed Dodo Terrace. The Dodo (as seen to the left of the image

perched atop four pillars) represented Lady Londonderry's father, Henry Chaplin, who was often

satirized as such for sitting in Parliament for such a long period of time. Charley, Lord

Londonderry, was symbolized by the Cheetah (to the right side of the image, in the middle of

and below the two griffins mounted on the Loggia), a pun referencing his rampant infidelity to

Lady Londonderry. Some of these figures reappear on the wall that delineates the western end of

the Italian Garden. Source: Image by R. Welch from 1925 photo album. Mount Stewart

Archives.

29

Figs. 11-13 show the detailing and sequential ordering of the herms located in the Italian Garden

at Mount Stewart. Source: Images taken by Stephanie N. Bryan on 15 June 2012.

swine's legs. The significance of the orangutans placed atop each herm is not evident. While the

gardens at Mount Stewart often served as a social setting for Lady Londonderry's circle of family

and friends, the herms undoubtedly stood as a symbolic gesture of her power and place in

society.

Exotic plants augmented the dream-like atmosphere she created at Mount Stewart. Lady

Londonderry described the effect such flora had on visitors accustomed to the typical British

climate: "Planted at the end of the clearing, but not so as to impede the very beautiful view of the

Mourne Mountains which are seen across the water some twenty to thirty miles off, is a group of

Pinus Pinea. Plants of Magnolia grandiflora, Exmouth variety, are growing near the woodland

30

side; Acacias have made great growth and there are many Cordylines. Arriving from the colder

districts in England for Christmas you seem to be in fairyland."

40

Lady Londonderry intimated her love of mythologies and high level of imagination in her

published writings. She described, "There is a feeling of enchantment about the place, and indeed

it is not hard to believe that in this most mystical land it is, even now, as much the magic island

of gods and initiates, as it was when the sacred fires flashed from its purple heath-covered, honey

scented, mountain tops and mysterious round towers on island and hill." A Neolithic tumulus

called the "cromlech" located on the Mount Stewart grounds prompted Lady Londonderry to

relate her gardening successes to the ancient race that once presided over the landscape. She

wrote, "Is it too great a fantasy to think these shades are with us now in this land of Heart's

Desire—that they themselves have taken Mount Stewart under their protection and lent a hand in

the fashioning of these grounds and glades, and made a garden blossom in the twinkling of an

eye, where none was before."

41

The imaginative sensibility that defined the garden experience was not limited to

permanent or tangible features as outdoor events in performing arts certainly enhanced the

feeling on special occasions. In an article entitled, "The Gardens at Mount Stewart," dated 3 July

1926, Mrs. T. J. Andrews wrote about a musical performance of Boughton's "Immortal Hour"

that occurred in the gardens. The author described the experience with great passion: "... Of the

dream and wonder of the singing, and the acting and the perfect setting of the scene, it is difficult

to write in any way that might not sound hyperbolic and sensational, but those who were there

40

Londonderry, "The Gardens at Mount Stewart," 527.

41

Edith Marchioness of Londonderry, "Mount Stewart: The Land of Heart's Desire," Northern Ireland 1, no. 8

(1926).

31

will never forget it; and to some it seemed to bring again the golden days of Greece when, in

open air theatres, music, and the drama, were brought into the hearts and lives of men."

42

1C) A Range of Talents:

Bringing Lady Londonderry's elaborate ideas into fruition required a combination of

skilled artisans. Her head gardener, Thomas Bolas, undoubtedly played a leading role in the

creation of the gardens. In an article, Lady Londonderry explained that Mr. Bolas was "... able

and willing to carry out designs from the roughest plans, and together he and I have worked out

the designs, whether of buildings, walls or flower-beds, on the actual sites."

43

Thomas Beattie, a

stonemason from Newtownards, who produced much of the stonework, garden buildings,

sculptures, and gateways, contributed to this local talent.

44

Additionally, Joe Girvan, a

stonemason from Greyabbey, erected many of the garden walls,

45

artist Edmund Brock supplied

designs for the topiary in the Shamrock Garden, and Robert Burnett, an ironworker from

Yorkshire, produced the wire frameworks to support the topiaries (Fig. 14).

46

The gardens thus became a vehicle for expressing the range of talents possessed by Lady

Londonderry and others. While most gardens similarly display a high degree of artistry in their

architecture and ornaments, the gardens at Mount Stewart were distinct because they mixed

original artworks with many common, often mass-produced items (Figs. 15-16), such as wicker

furniture.

47

This assortment added to the overall eclectic nature of the gardens.

42

Londonderry, "Mount Stewart Garden Book No. 1 1922-1927," 159.

43

Londonderry, "The Gardens at Mount Stewart."

44

Londonderry, "Mount Stewart Garden Book No. 1 1922-1927," 54.

45

Ibid., 27, 32.

46

Ibid., 36-38.

47

Londonderry, "Mount Stewart Gardens 1927-1936," 2.

32

Fig. 14 shows ironworker Robert Burnett from Yorkshire meticulously creating the wire frame

used for one of the topiaries that Lady Londonderry placed atop the hedge in the Shamrock

Garden. Images always depict Mr. Burnett dressed in a full suit and hat, which indicates the

pride he took in his profession as an artisan. Source: Londonderry, Edith, Marchioness of.

"Mount Stewart Garden Book No. 1 1922-1927," 37.

33

Fig. 15 (above) shows advertisements for common garden ornaments that caught Lady

Londonderry's attention. Source: Londonderry, Edith, Marchioness of. "Mount Stewart Gardens 1927-

1936," 2.

Fig. 16 (below) shows how Lady Londonderry filled her gardens with common items, such as

the wicker chair and table located in the bottom left corner of the image. Source: Mount Stewart

Archives.

34

2) Plant Selections and Introductions

2A) An Exotic Collection

Lady Londonderry had an unquenchable thirst for "unusual," "uncommon," and "rare"

plants.

48

She filled her gardens with an array of plant types, such as bulbs, vines, shrubs, and

trees. On 16 September 1926, Sir Herbert Maxwell wrote to Lady Londonderry that, "The lust

for lilies is a contagious disease as deadly as rhododenronitis, from which you suffer incurably

already." A visit by Lady Londonderry in 1922 to the gardens at Rostrevor House, which Sir

John Ross of Bladensburg had created on the slopes of a sheltered hill overlooking Carlingford

Lough in County Down perhaps, triggered this "lust." Lady Londonderry reminisced, "I shall

never forget the wonder and amazement of that visit ... in which Sir John initiated me into the

many and marvelous trees, shrubs and plants from countries all over the world, that could, with

knowledge and skill, be grown by the seaboard of County Down. It is due to Sir John's

encouragement and knowledge and the help he gave me, together with countless shrubs of all

descriptions, seeds, and cuttings that he sent here, that the gardens at Mount Stewart contain so

many tender and beautiful things."

49

An article about Mount Stewart from the Naturalist Field Club offers insight into the

variety of rare and interesting plants that Lady Londonderry had already acquired by 1926. The

author described many exotic plant species located around the Pergola and West Garden as

follows: "... Eucalyptus trees—E. globulus—the Blue Gum of Australia, growing at Mount

Stewart to a height of 85 feet; a New Zealand Tree fern

—Dicksonia antarctica—and the rare

Californian shrub Dendromecon rigidum, with its big yellow flowers ... The Pergola is planted

with twenty species or varieties of Australian and New Zealand Acacias, the Club Palm,

48

These terms recur frequently throughout the letters of correspondence, seed lists and plant catalogues, and article

clippings collected by Lady Londonderry.

49

Edith Marchioness of Londonderry, Retrospect (London: Frederick Muller Ltd., 1938).

35

Cordyline australis; the Chusan Palm, Chamaerops humilis; Ginger Plant, Hedychium Greenii;

Japanese Banana, Musa japonica; Jersusalem Sage, Phlomis fruticosa; Chilian Nut, Guerina

avellana; Cork tree, Quercus subes; Bottle brush Tree, Metrosideros; Loquat, Eriobotrya;

Vibernum rhytidophyllum from China; Eucryphia cordifolia and Crinodendron Hookeri from

Chile with Desfontainea spinosa and some fine lilies, Lilium auratum, L. Henryi, L.

Pardalinum..."

50

This quote offers a mere glimpse of the countless species Lady Londonderry

introduced to Mount Stewart, from countries such as Australia, New Zealand, Tasmania, Chile,

Italy, the United States, India, China, and Japan.

Lady Londonderry not only desired such plants for their exotic qualities, but also because

she associated them with special places or stories. For example, in a letter dated 28 January 1938

Arthur Wauchope wrote, "...I am now sending you some of these (Olive seeds from

Gethsemane]... I am also sending you a few pods of seeds of the Judas tree which you might like

to have, also from the Holy Land."

51

A letter dated 29 January 1932 from Sir Lionel Earle

provides further insight. Earle wrote, "Our greatest plant treasure at the moment is Prostanthera

coccinea from Kangaroo Island. Seeds of this were collected for me by a lady who obtained a

permit to visit the Island to paint. The Island is a close preserve for a very rare flora and fauna.

This Prostanthera is a glorious scarlet flowered shrub requiring a cool greenhouse in this country

but eventually it may prove hardy in Ireland, we cannot say yet."

52

The collection of rare, exotic,

and often expensive ornamental trees and shrubs at Mount Stewart became conversation pieces

in the landscape, replacing the extravagant follies that had characterized the former English

landscape gardens.

50

Edith Marchioness of Londonderry, "Mount Stewart Garden Book No. 2 1922-1927," (1922-1927), 4.

51

Edith Marchioness of Londonderry, "Newspaper Clippings, Letters, and Notes " (c. 1950-3), 189.

52

Ibid., 1.

36

While collections of rare and exotic plants also characterized some gardens of Lady

Londonderry's day, Mount Stewart stood apart from other contemporary Irish and British

gardens, such as Rowallane and Bodnant, because its garden architecture and ornaments also

reflected unusual and foreign qualities. This is evident in an article dated 14 April 1930 by R. J.

Welch, which describes a group of women from Belfast visiting the gardens at Mount Stewart.

Welch wrote, "The models of the long extinct Dodo, that unwieldy bird of the Island of

Mauritius, in the Indian Ocean, were new to the visitors, none of whom had ever seen Dodo

models before. ...through the Dodo gateway ... the fine tall eucalyptus trees were pointed out; the

long strips of bark that they shed periodically were examined with interest. They were told that

these big blue gums from Australia or Tasmania were among the tallest trees in the world in their

native forests, and that they fruited abundantly at Mount Stewart, which they do not do, we are

told, even in the South of England."

53

2B) A Network of Exchange:

Beyond ample income, the relationships forged between Lady Londonderry and others

who possessed shared gardening interests made it possible for Lady Londonderry to procure and

cultivate such rarities. Lady Londonderry's network grew over time to include neighbors,

nurserymen, gardeners, horticulturalists, botanists, and plant- hunters, many of which Lady

Londonderry considered friends. These horticultural experts and friends included many notable

gardeners: C. W. James; Lord Aberconway of Bodnant; Hugh Armytage Moore of Rowallane;

Lord Digby; Arthur Dorrien-Smith of Tresco Abbey; Lord Dunleath of Ballywalter; Arnold

Forster of Zennor; Colonel Grey of Hocker Edge; Lord and Lady Loder of Leonardslee; Lady

Linlithgow of Hopetoun; Henry McIlhenny of Glenveagh; Lionel Rothschild of Exbury; Lord

53

Ibid., 88.

37

Stair of Lochinch; J.B. Stevenson of Tower Court; Guy Wilson of Broughshane; and the staff of

the Botanic Gardens at Edinburgh and Hyde Park Gardens. Lady Londonderry’s horticultural

network also included many nurseries and nurserymen: W. A. Constable; Hillier Nurseries;

Ingwersen Nurseries; Olive Murrell of Orpington Nurseries; Perry Nurseries; Reuthe Nurseries;

W. and L. Slinger; and Veitch Nurseries. Notable plant-hunters Frank Kingdon-Ward, George

Forrest, Clarence Elliot, and Joseph Rock also played a role in this vast community of plant

enthusiasts.

54

A letter dated 1 February 1930 provides a glimpse into the extent of this network of

exchange and the types of people involved. In the letter, a Spanish correspondent wrote, "I have

the honour to announce the despatch [sic] from Sevilla to Liverpool of forty olive-tree shoots and

forty orange tree plants, shipped on January 30 last, on board s.s. "Cervantes"; all ordered by His

Grace the Duke of Alba."

55

A letter dated 16 March 1940 from Norman G. Hadden shows the

reciprocal nature of this network. He wrote, "Thank you very much indeed for the lovely box of

plants which has just arrived from Mount Stewart; it is truly kind of you to send them to me and I

am immensely grateful. ...Would a few small seedling of Leptospermum sericeum be of use to

you? I will be delighted to send them."

56

Correspondents not only dispersed seeds but horticultural knowledge as well. For

example, in a letter dated 6 June 1930, Clarence Elliot wrote, "I have also here an interesting

Palm ... its name is Jubea spectabilis and is a native of Chile ... It is rapidly becoming

exterminated, and the Chilian [sic] people cut the trees down for a sort of honey sap which they

extract from the trunk ... It likes a position where its roots can get plenty of moisture."

57

A letter

54

Casement, "Mount Stewart Garden Archives and Historical Survey 1917-1959 Part One," 19-20.

55

Londonderry, "Newspaper Clippings, Letters, and Notes " 3.

56

Londonderry, "Mount Stewart Gardens 1937," 21.

57

Londonderry, "Mount Stewart Gardens 1927-1936," 76-77.

38

dated 28 June 1933 from Mrs. Maud White provides another example. She explained, "The

curator of the Brisbane botanical gardens, Mr. Bick, is sending you a number of seeds to try, and

I asked him to send directions with them for growing ... Then a nurseryman called Wood, in

Brisbane, is sending you 1 1/2 dozen Comquat [sic] trees, also a scented eucalyptus, a coral

flowered eucalyptus, and I think, a brown, scented boronia. The latter grows well in undisturbed

ground, in a damp fairly shady place. It grows wild in the forests near Melbourne. It likes the

same treatment as Ericas. It has a flower like a little brown hollow berry lined with yellow, and a

most enchanting scent."

58

While most letters regarding plant materials contained instructions from their senders,

Lady Londonderry recognized that it required a degree of trial and error to determine suitable

growing conditions for individual plants at Mount Stewart. In a letter dated 26 March 1938, she

wrote to Sir Mark Collett, "My own experience has been that no-one can say definitely what

plants will flourish in any particular garden. I think the site and soil affect the plant as much as

the climate ... Every year we make experiments with delicate plants, and our latest success has

been with Clivias, which are doing very well at the foot of a low wall right in the open."

3) Plant Arrangements

3A) Color:

For her gardens, Lady Londonderry preferred plants that displayed hot-colored flowers.

Crimsons, maroons, wines, oranges, fuchsias, magentas, and bronzes consistently dominated her

rare plant palette. Lady Londonderry was careful not to haphazardly place these selections

throughout the landscape; rather she experimented with many color combinations to achieve a

dramatic display acceptable to her discerning eye. For example, a summer 1938 garden book

58

Ibid., 120b, 21a, 21b.

39

entry suggested to "put wine coloured dahlias instead of orange—substitute wine for orange

everywhere —much more contrasting,"

59

This selection, however, failed to meet Lady

Londonderry's expectations and the following summer she wrote, "revise this garden not enough

colour for autumn."

60

Lady Londonderry's garden books further suggest that she strove to have her color

selections reflect seasonal tones. In an autumn 1922 garden book entry, she instructed Thomas

Bolas to "replant [the large West Garden] beds using Dahlias Orange King and Insulande

[varieties] for autumn effect"

61

By 1924 she suggested there was "too much yellow for Autumn

effect—Dahlia Insulande to be removed —Fire Dragon excellent order more."

62

By 1925, she

seemed pleased with the results and noted that "from spring to autumn always a succession of

bloom."

63

Following a visit to Mount Stewart a decade later, author G. C. Taylor described the

dramatic effects of color that Lady Londonderry had achieved with different pairings: "Many

uncommon shrubs, such as the lovely Abutilon vitifolium (both the blue and white forms), those

two handsome Chilian [sic] evergreens, Tricuspidaria lanceolata and Embothrium coccineum,

fuchsias, brooms, cistus, heaths, and Acacia sauveolens and other species, provide a permanent

furnishing in the beds and are reinforced for the sake of colour effect in the spring by masses of

tulips carefully arranged to provide a definite colour scheme."

64

Lady Londonderry’s garden books contain article clippings that give insight into how she

applied color theory to landscape design. For example, an undated article from The Garden titled

"The Use of Scarlet Flowers" suggested that such flowers were effective either paired with ivory

59

Londonderry, "Mount Stewart Gardens 1935," 38.

60

Londonderry, "Mount Stewart Garden Book No. 1 1922-1927," 39.

61

Londonderry, "Mount Stewart Garden Book No. 2 1922-1927," 19.

62

Ibid.

63

Ibid., 27.

64

G.C. Taylor, "Mount Stewart-II. County Down. A Seat of the Marquess of Londonderry.," Country Life (1935):

382.

40

tones or "grouped fairly boldly in front of a solid dark background, preferably of a yew."

65

The

article responded to a previous one called "Scarlet and Grey in the Garden," which instead

recommended pairing intense scarlet tones with cloudy blues, purples, and silvery grays.

Both articles influenced Lady Londonderry's use of color. For example, a spring 1925

garden book entry for the Shamrock Garden called for the "borders between yews and paving to

be mostly orange and red—the latter to predominate."

66

Additionally, Lady Londonderry noted

on a 1925 plan for the eastern parterre in the Italian Garden that there should be "nothing but

scarlet, gray, or white in all beds" (Fig. 17). Lady Londonderry later wrote, "On the western half

of the garden the colours are intended to shade from blood-red into pinks, pale yellows, mauves

and purples, also silvery-greys ... The eastern half is kept for scarlets and orange, with dark prune

colours or mulberry and blues ... All the beds have a hedge of white heather."

67

While Lady Londonderry clearly drew inspiration from periodicals on how to group

colors, her library collection surprisingly did not contain any books on color theory, such as Gertrude

Jekyll's Color in the Flower Garden.

In a 1923 plan for the roses located within the Walled Garden,

Lady Londonderry selected hundreds of "rose," "blush," "red," "orange," "orange pink," "buff,"

and "white" roses and called for the "dark plants in the center shading outwards."

68

Her other

plans for mixed beds of herbaceous plants, vines, shrubs, and trees often repeated this "sunray"

pattern with gradations of color.

69

For example, in the eastern parterre of the Italian Garden hot

reds and oranges radiated from the center while a touch of complimentary blue color added

contrast along the outer rim (Figs. 17-18).

65

Londonderry, "Mount Stewart Garden Book No. 2 1922-1927," 141.

66

Ibid., 130.

67

Londonderry, "The Gardens at Mount Stewart," 525.

68

Londonderry, "Mount Stewart Garden Book No. 2 1922-1927," 5.

69

Londonderry, "The Gardens at Mount Stewart," 530.

41

Lady Londonderry's color choices remained relatively unchanged over time. Her later

plans, however, progress toward intermixing complimentary colors (Fig. 18). These plans also

reveal an evolution in Lady Londonderry's plant selections and groupings. For example, Lady

Londonderry repeated the same planting scheme for each of the eight large beds in her 1925 plan

of the eastern parterre in the Italian Garden (Fig. 17). This repetition produced a rather simple

and balanced effect. Her 1929 plan, on the other hand, shows increasing complexity and

asymmetry as she applied a different planting scheme to each of the eight large beds (Fig. 18).

Her later, highly irregular grouping of mixed plant materials was an uncommon way to treat a

parterre. This unusual treatment of the planting beds was part of Lady Londonderry's strategy to

create a succession of seasonal color. It also reinforces that Lady Londonderry was fascinated

with the "magical" qualities of plants, and the gardens truly became a means for her to act as an

enchantress and make the Circe myth a reality in her life.

42

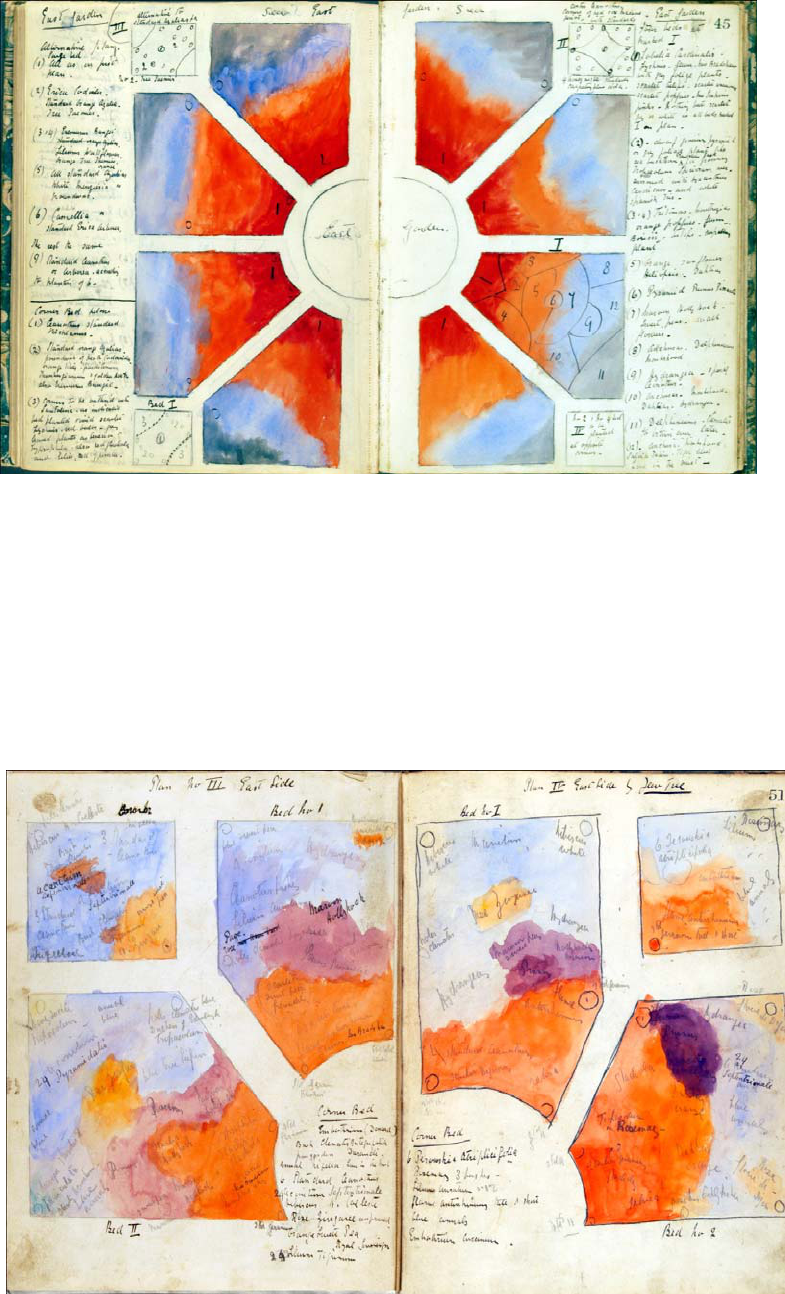

Fig. 17 (above) shows a 1925 design for the eastern bed in the Italian Garden, taken from Lady

Londonderry's garden book. For this particular group of flower beds, Lady Londonderry set off

the central hot reds and oranges with complimentary blues along the edges. Source: Londonderry,

Edith, Marchioness of. "Mount Stewart Garden Book No. 1 1922-1927," 44-45.

Fig. 18 (below) shows a 1929 design for the upper portion of the same planting beds as seen in

Fig. 17 (above). While the color choices mostly remained the same, Lady Londonderry

intermixed colors and developed schemes that became more complex. Source: Londonderry,

Edith, Marchioness of. "Mount Stewart Garden Book No. 1 1922-1927," 50-51.

43

3B) Fragrance:

In addition to color, Lady Londonderry highly valued intense fragrance in the landscape.

She aspired to fill her gardens with curiously fragrant plants, such as Boronia serrulata, which

Stuart Low Co. described in a letter dated 11 April 1940 as having "a haunting scent" and

appealing "to people in a quite occult manner."

70

She meticulously recorded how her plants

performed, grading them as "deliciously scented," "one of the best," "quite good,"

"disappointing," and so forth. The gardens at Mount Stewart can thus be characterized as a

continual exercise in experimentation and improvement; a place representing the owner’s high

aesthetic and horticultural aspirations.

In 1925, a new rose was named "Dame Edith Helen" after Lady Londonderry and an

article by C. A. Jardine asserted that "There is no better lasting Rose extant, some blooms having

kept even ten days, perfuming the room all the time."

71

Lady Rose recalls that her grandmother

declared, "No scentless rose would ever find a home at Mount Stewart!"

72

In addition to roses,

Lady Londonderry filled her gardens with other fragrant plants such as lilies, eucalyptus,

rosemary, honeysuckle, daphne, edgeworthia, rhododendron, and verbena. Lady Londonderry

integrated many of these fragrant plants into her formal beds. In one of her garden books, she

saved an undated article entitled "A Nosegay Garden" and thus may have applied author F. A.

Hampton's idea of "making a permanent scent bouquet in a formal frame."

73

A letter to Mrs. Grieve dated 17 February 1938 suggests that Lady Londonderry

considered other creative ways to bring fragrance into the garden. In the letter, Lady

Londonderry explained that the fragrant "... Chamomile I bought from you last year ... is being

70

Londonderry, "Mount Stewart Gardens 1935."

71

Londonderry, "Mount Stewart Gardens 1927-1936," 52.

72

From a conversation between Stephanie N. Bryan and Lady Rose Lauritzen on 15 June 2012.

73

Londonderry, "Mount Stewart Gardens 1927-1936," 124.

44

made into a lovely lawn." By 1940, Lady Londonderry recorded a number of "Uncommon seeds

for scents" such as Escacum affine, Maurandia eruchescens, Schizopetalon Walkeri, Nycterimia

capensis.

74

She also wrote her ideas for "A Scented Border for the evening," which included

"tobacco plants, night scented stocks, almond trees, pink daphnes, Mignonette, stocks, Madonna

lilies, Salonika, Philadelphus, Vibernum, lavender, Artemesia, Clerodendrum, jasmine var.

Honeysuckle, Sweet Briar, L. auratum, Hamamelis, [and] sweet scented cyclamen."

75

Lady

Londonderry also brought the sweet aromas indoors by filling the house with cuttings and forced

bulbs, in addition to her homemade potpourri. An entry in her garden book from summer 1925

noted that she cut "150 roses and 140 roses from the two year old beds—only full blown

blooms—for potpourri ... hundreds of roses still left."

76

3C) Season:

Lady Londonderry consistently looked for ways to extend the season of exceptionally

fragrant and colorful flowers in her gardens. One strategy included selecting many plant varieties

that nursery catalogues categorized as early or late bloomers. This theme dominated the article

clippings that Lady Londonderry retained in her garden books. Among these articles were the

following titles: "Winter and Summer Irises,"

77

"The Best Late Heaths;"

78

"Winter Flowering

Heaths,"

79

"Shrubs that Flower Late Summer,"

80

"Early Bulbs,"

81

"Early Shrubs of Merit,"

82

74

Londonderry, "Mount Stewart Gardens 1937," 82.

75

Ibid.

76

Londonderry, "Mount Stewart Garden Book No. 1 1922-1927," 11.

77

Ibid., 58.

78

Ibid., 81.

79

Ibid., 82.

80

Londonderry, "Mount Stewart Gardens 1927-1936," 43A.

81

Edith Marchioness of Londonderry, "Garden 1935," (1935), 78.

82

Londonderry, "Newspaper Clippings, Letters, and Notes " 63.

45

and so forth. Her garden books often included her own "suggestions for flowering trees and

autumn colour" such as "at back of Rhododendron walk [to] give colour early and late."

83

In an article for the Journal of the Royal Horticultural Society, Lady Londonderry

pointed out that she grouped vines with trees and shrubs as another tactic to extend the season

and create a succession of blooms. She explained her process: "Clematis grows over and through

large bushes of Erica arborea, and Prunus pissartii is covered with Tropaeolum speciosum.

Clematis also looks lovely grown through standard trees of Wisteria. The shrubs lend themselves

to this dual purpose: not only are they lovely when in bloom themselves in spring and early

summer, but they display a mass of colour during the late summer and autumn months."

84

In her

garden books, Lady Londonderry often noted species in her plant order lists and saved articles

about climbers that would suit this "dual purpose."

85

As part of the aristocracy, Lord and Lady Londonderry spent much time at their home in

London socializing and engaging in political affairs. Yet, such a concern for seasonal effects