Critique: a worldwide student journal of politics

Cultural Fractionalization and Policy Response

to COVID-19: A Comparative Study on the

Case of OECD Countries

Yidong Yang

China Foreign Affairs

University Beijing, China

Abstract

This study investigates the relationship between cultural fractionaliza-

tion within a state and the stringency of COVID-19 policy responses

in 38 countries. Using quantitative metrics including ethnic, religious,

and linguistic diversity to measure cultural fractionalization, the study

applies a standardized process of quantitative measurement to analyze

the data. From a constructivist perspective, the study argues that do-

mestic policies are shaped by the knowledge structures within society

and finds that countries with more cultural fragmentation tend to have

looser quarantine policies, while those with more cultural homogeneity

tend to have stricter ones.

For three years, COVID-19 had been raging across all countries,

during which every country stood on the same ground to fight the

pandemic, which made a great impact both on economic growth and

political development. There is no doubt that a pandemic is a difficult

problem for all counties because no country has had adequate

knowledge about the disease and potential solutions. Some may argue

that a pandemic is inherently different from other crises, such as floods

or earthquakes, because the cause of the crisis is clear, but during the

very first stage of the pandemic, it was not (Rodriguez et al. 2007). Yet

these uncertainties caused different governments to act quite

differently under pressure to put forward their policies in order to stop

the spread of such a novel disease and to deal with the disastrous

impacts. Global action on the crisis has been triggered, but not at the

same moment, nor in the same way, or with the same stringency.

Measures like quarantine, distancing, closure of schools and airports,

testing, and face-covering for example, are the most common policies

Fall 2023

2

a government would adopt, but even though, the balance of the

mixture and the stringency of each policy differs a lot among all

countries.

It must be said that the pandemic has been a highly valuable

opportunity for all political science research since all counties have

responded to the same crisis in different ways which would provide us

with sufficient information on how specific states have acted during

the crisis and what could have caused the states to act in this way. Thus,

this paper would like to make full advantage of the opportunity to

practice a thematic study on world politics

During the ongoing pandemic, many policy-related aspects

require further research. However, this article focuses on the policies

that countries put forward to control the spread of the disease, which

include full-scale to partial lock-downs, quarantine measures of various

intensities and models, social or physical distancing, various ‘track, test,

and trace’ measures and so on. To be clear, the speed and timing of

political response to the pandemic could also differ among countries,

but the timeline of response depends on when countries confirmed

their first cases of the virus, which makes the evaluation of the timing

highly uncertain. Because it cannot be sure whether countries act on

the discovery of the virus outside the country or their own first

confirmed cases, or both.

One may question how these different policy responses are

related to the factors within states. This research believes that in this

matter, that in this matter is the domestic culture has an impact on

policymaking, it may not be the most influential factor but still has its

effects directly or indirectly. This article take culture as an idea itself.

Further discussion on methodology will be provided below. To begin

the research, it is be assumed that domestic culture will somehow affect

the policy-making process even related to an emergency such as the

COVID-19 outbreak, based on common sense and true faith,

To simplify the problem, this research takes the stringency of

different policies as the dependent variable, which is an index

measured on twelve different indicators including testing policies, face-

Critique: a worldwide student journal of politics

covering policies, and travel controls. And to treat cultural

fractionalization within states as the independent variable, and

question whether there is a connection between these variables or not.

Cultural fractionalization is an index measuring whether the

culture within a country is formed in a homogeneous or a

heterogeneous way and how diversified it is, which is surely an inclusive

concept that can be measured from many aspects. This article defines

culture in a boarder sense that differs from political culture studies,

where scholars consider only civic culture. In this short paper, three

key indexes would be measuring diversity levels: ethnic diversity,

religious diversity, and linguistic diversity. To be clear, it is unclear how

the three factors are independently related to outcome. It is unclear

whether any cultural diversity is related to policy stringency in any way.

The main reason to adopt such a method of dividing cultural

fractionalization is only that it is at least one of the measures mostly

used by researchers to study the problem of cultural fractionalization.

At least one of the measurements must be adopted to measure cultural

fractionalization, for the continuation of the research, and indeed, the

trichotomy of culture could be a better solution. And these three

indexes are intuitive, quantitative, and easy to evaluate, as this article

would argue further below.

Literature review

In recent research, many scholars have used the comparative

method to question why different policy responses between different

countries occurred, but most of those studies lack discussions of

domestic cultures.

Existing institutional arrangements can be a key factor in

influencing the behavior of governmental responses to public health

crises. Capano, Howlett, Jarvis, Ramesh and Goyal demonstrated how

preparation and experience could impact leaders’ decisions on fighting

the pandemic (Capano et al. 2020). Countries were divided into four

categories, some of the Asian countries that fought with SARS-CoV-

1, H1N1, and MERS in their early years would deal with the recent

pandemic more steadily and confidently. For example, China and Italy,

where the virus first affected, were not prepared to deal with the novel

virus, which caused chaos at the beginning. Preparation has been

identified through their research as a key factor, but it fails to help

Fall 2023

4

explain why countries with advanced public health systems show very

different policy responses to the pandemic. This article would like to

focus more on political institutions rather than on medical experiences.

In addition to public health management, governmental and

political factors can have various impacts on controlling the pandemic.

Toshkov, Carroll and Yesilkagit, asking what factor could account for

the various response to the first wave of COVID-19 in European

countries, built their research on variables including (1) general

governance capacity, (2) crisis management preparedness, (3) health

care specific capacity and organization, (4) political institutions, (5)

government type, (6) party-political ideology, and (7) societal factors

(Toshkov and Yesilkagit 2021). They were successful in organizing

different factors into groups and the result is very comprehensive. But

in contrast to their intricate independent variables, they set their

dependent variables rather succinctly, which only measure school

closure and national lockdown. The term ‘cultural factor’ that this

article would like to argue in this paper is similar to the term ‘societal

factors’ mentioned above, but the authors measured the quality of

society only by a survey about three factors of societal value, on which

this article would tend to dig deeper into the core of the question to

understand where culture lies.

About how to sort out different measures adopted by

governments, Nihit Goyal and Michael Howlett, use CoronaNet as a

database and sort different policies into a dataset in the order of

semantic categories, and keep notes on how long each policy takes its

effect, from which they obtained their exciting findings (Goyal and

Howlett 2021). The paper concludes that there are 16 key policies in

response to COVID-19 and thus the authors questioned how it is

related to governing resources. It’s interesting that they also conducted

research on the key terms associated with the discussed policies, and

measured these terms by their occurrence and exclusivity, by doing so,

the authors aimed to measure the balance of the policy mix. Their idea

of organizing the data and sorting them into groups is enlightening for

this research, and this research will be using a similar method.

Critique: a worldwide student journal of politics

Similarly, in searching for the factors affecting different policy

responses, Moshe Maor and Michael Howlett also conducted their

research by comparing different political responses among countries

and concluded that three independent factors could affect politicians

in making their policies during the COVID-19 pandemic (Maor and

Howlett 2020. The three factors mentioned in the paper are

psychological factors, including elite panic and limited government

attention spans, institutional factors, implying the level of government

effectiveness, and strategic factors, including political considerations.

This article will question a similar research problem but by addressing

the influence of cultural factors, the differences is that their previous

article proposed the factors after asking the question, while this article

will do the opposite.

Different from foregoing comparative research on mass data,

Paula Serafinia and Noelia Novoselb did regional research on

Argentina alone, questioning how local cultural understanding

underpins COVID-19 policy response (Serafini and Novosel 2021).

Research found that freelance workers are suffering the most from the

control policies. In response, Argentina adopted a series of measures

to protection of cultural works. In the paper, the authors conclude that

Argentina’s diverse culture made the government adopt a caring but

limited cultural policy of solidarity during the COVID-19 pandemic.

The following research will be conducted not in one country alone, but

in 38 different countries, but the research will be looking into the effect

of cultural factors similarly. There is no doubt that culture had a great

influence on pandemic restrictive policies, but how it is related, was

not clarified in the previous paper.

In summary, while all these scholars tried from different

perspectives to question what could be the factors in the complex

formation process of policy responses to COVID-19, this article

attempts to have cultural and social dimensions to understand the

various policies. It should be noted that sorting out different factors

during the decision-making process was never an easy task, before or

after the pandemic, but the novel virus brought us much closer to the

secret answer of policy decision-making than did any of those political

events of the past since all countries act towards the crisis

synchronously. But the questions remains for scholars from all schools

of thought. For example, prior research on choices of policy responses

Fall 2023

6

would largely ignore the role of domestic culture and any qualities to

do with it, such as cultural diversity, identity, and national character,

which will be the main focus of the discussion in this short paper.

Conceptual framework

This article seeks to explain the different processes of

policymaking among countries by applying a comparative method to

the study. It argues, that the COVID-19 crisis provides a golden

opportunity for any political comparative studies because it can bridge

one of the major gaps between political facts and scientific methods

which is the replication of the same motivation. In this paper, the

article holds regional culture as the independent variable while

examining the ‘laboratory’ of the world’s political system, for

comparative policy outcomes. While the article strives to take a hard

science approach in its research, it recognizes that there are many

intermediate variables that cannot be thoroughly measured in the

‘black box’ of decision-making, which inevitably leads to differences

between politics and hard science. However, the paper will be as

precise and careful as possible in its research as it can be. It is also

considered ‘scientific’ due to its adoption of a behaviorist perspective.

In examining political phenomena, this research will focus only on

those that are observable in order to avoid epistemological critics as

much as possible. I’m aware that post-modernism distrusts any

interpretation without sorting out the horizon one’s looking, from

which one may even conclude incommensurability between paradigms,

but this article would rather abandon the possible falsehood of

epistemic intermediaries but turn to entities itself, with so-called

ontological turn. However, in this paper, the research would like to

simplify the philosophical analysis only to show that a spectator can

annotate a political phenomenon.

While most statistical researchers tend to neglect the explanatory

discussion in their study, this article attempts to argue in a

constructivist way how policies are formed radically by shared ideas

among actors and how actors act based on the knowledge they have

Critique: a worldwide student journal of politics

for the society, which eventually reinforces the knowledge itself. It

adopts a perspective of holism and idealism in order to make such an

argument. Culture, as this article argues, does not present the

institution itself, implying a causal relationship between culture as a

starting point and policy as result, but rather a constitutive relation

between them. The detailed arguments will be presented below.

This article seeks to explain the result from a constructivist

perspective, in contrast to the causal relations argued by most scholars.

Culture, or shared ideas, among individuals can significantly impact

how people act towards policy decisions. One may ask what kinds of

shared ideas could affect policymaking because there are so many kinds

of shared ideas in societies. These may include norms, rules, identities,

ideology, discourse, or ideas themselves, some of them may affect the

policymaking process while others may not. Reality is not as important

because all actors interpret it differently. As constructivist theory

suggests, both the public and politician act based on of their

knowledge (or prior understanding) of the world, and the interaction

reconstructs or enhances their knowledge of others. It is easy to

imagined that the prior understanding direct both ends of

policymaking and forms the culture between them.

Methodology

This paper gathered its data on policies mainly from two

resources. CoronaNet is a project that collects all policy responses

made by governments related to COVID-19, from the beginning of

the pandemic. Over 500 researchers gathered data from 195 cases to

collect as much information as possible. The project also includes with

a table of COVID-19 Policy Intensity Scores, which will be explain and

be referred to in a later section of this paper. Another source of policy

data is OurWorldinData.org which has also done an excellent job of

collecting information on the pandemic. Researchers on the program

have created 3165 charts addressing the world’s largest problems,

including many related to the pandemic. On their site, policies are

separated by time and region.

The ethical, religious, and linguistic diversity indexes used in this

paper were collected from the work of Alesina and Ferrara et al. who

compared ethnic, linguistic, and cultural fractionalization across 215

countries (Alesina et al. 2003). They gathered data on ‘ethnic

Fall 2023

8

composition’, ‘language’, and ‘religious affiliation’ from yearbooks of

Encyclopaedia Britannica, which collect data from official government

reports and national censuses. The fractionalization of the three

variables is represented by a numerical result from the ‘one minus the

Herfindahl index’ formula, which varies from 0 to 1. A result of 0

indicates a perfectly homogeneous countries, while a result of 1 refers

to the most fractionalized countries. This formula calculates the

probability that two randomly chosen individuals from a country

belong to different ethnic groups, speak different languages, or follow

different religions. The calculation only considers groups comprising

more than one percent of the country’s population; smaller groups are

not taken into account.

This paper selected 38 countries that are members of the

Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD)

for analysis. These countries are generally highly developed, and vary

in size, population, culture and faith. The selection of countries from

different continents allows for a broad range of development levels

and policy systems to be analyzed. Membership in the OECD signifies

a country's interest in participating in globalization and could also be

seen as an indication of their economic development and

modernization. The process of selection can be considered

representative and neutral as the set of countries wasn’t chosen by any

scholar or organization but rather arose itself throughout history.

In choosing the countries for this study, the availability and

credibility of social survey data was also taken into consideration.

Developed countries tend to have more mature and reliable social

survey systems, often with independent agencies responsible for their

administration, such as the Bureau of Economic Analysis in the US,

INSEE in France, or the Office for National Statistics in the UK. As

an epidemic, COVID-19 spreads through the circulation of materials

and people. Therefore, relatively developed countries, which have a

higher level of globalization and were more likely to come into direct

contact with the virus at the beginning of the outbreak, were selected

for this study. On the other hand, less globalized countries may not

Critique: a worldwide student journal of politics

have had sufficient exposure to the virus at the beginning of the

epidemic, as was the case for many less developed countries in Asia,

Africa, and Latin America at the time this paper was written.

Globalization was therefore an important factor in the selection of

countries for this study.

Secondly, the fact that most OECD countries are developed gives

their governments greater confidence in their ability to make rational

and well-considered decisions. The economic success of these

countries also reflects the strength of their government and the

cooperation of the public. In comparison to less developed

governments, developed and complete governments are better able to

respond to their domestic culture, making them more valuable subjects

of study. Without a mature bureaucratic system and policy-making

process, political decisions made by the government may be unstable

and inaccurate, and therefore lack value in research. As mentioned at

the beginning of this research, it is essential to ensure that domestic

cultures in the countries have at least some influences on the policy-

making process, which can be achieved through a mature bureaucratic

system. It is not to say that undeveloped systems are incapable of this,

but rather that it would be difficult to ensure. In the development of

political systems, those that act stable and accurately and interact with

their cultural groups tend to succeed, while those that do not either

reform or face failure.

Another reason for the paper's choice of OECD countries is to

exclude China from consideration due to its unique position in the

COVID-19 timeline as the place where the virus was first discovered.

Other countries faced the virus more or less simultaneously, so

excluding China could potentially reduce uncertainty resulting from

the diachronic sequence. From today's perspective, China has indeed

implemented a different pandemic policy compared to other countries,

so it may be advisable to exclude China from the list of options.

Taking these considerations into account, it can be argued that

OECD countries are a good choice for this research as they represent

a wide range of world cultures, from Asia to America, and from

Christian to Islamic. This diverse selection will likely increase the

sample size and credibility of the research. While the OECD countries

may not be an exhaustive choice, they provide a balance between

comprehensiveness and rationality.

Fall 2023

10

The question then arises about policy responses. There are several

ways to classify these responses. Goyal and Howlett (2021) divided

them into 16 groups: curfew and lockdown, border restriction,

quarantine and tracing, government services, information

management, (non)essential business, testing and treatment, public

gathering, education, physical distancing, funding and stimulus,

advisory and warning, protective equipment, public event, health

screening, health resources. It can be seen that M. Howlett et al. have

adopted a broad concept in the evaluating policy responses, including

those aimed at stimulate economic growth and social propaganda. G.

Capano et al. classified different policies into 18 groups: tax payment

deferral, tax regulation relaxation, business loan, leave and

underemployment, travel advisory and restriction, social distancing,

monetary policy, health facilities, medical supplies, social security,

immunization and treatment, patient care, information and advice,

support for the vulnerable, school and university closure, COVID-19

epidemiology, financing relief, health-care spending. G. Capano et al.

have chosen an even border concept in defining the policy responses

for COVID-19, including epidemiology research and financing. In the

‘CoronaNet’ research project, researchers classified policies into 6

different categories, which are business restrictions, health resources,

health monitoring, school restrictions, mask policies, and social

distancing. The classification is rather rough but easy to manage for

such a sizeable project like ‘CoronaNet’.

This article would follow the classification peovided by T. Hale,

N. Angrist et al., which is as follows: school closure, workplace closure,

cancel public event, restriction on gathering, closed public transport,

public information campaigns, stay-at-home, restriction on internal

movement, international travel control, testing policy, contract tracing,

face covering, vaccination policy. These policies are specific and easy

to measure and can be assigned to a index to measure stringency of

each.

The point in time chosen for sampling in this research was mid-

March 2020, when all countries were just beginning to take action

Critique: a worldwide student journal of politics

against the threats of COVID-19. The reason for not choosing an

earlier or later time is that any earlier time would not have been

sufficient for countries to realize the severity and novelty of the virus

and to take serious action against it, and any later time would allow

countries to imitate the methods of others and make their actions

increasingly homogeneous. There is evidence showing how countries

imitate each other in response to the threat of COVID-19. However,

mid-March may be the golden period when each country acted toward

the crisis independently, without any paradigms to follow. The policy

stringency index calculated is presented in Table A2.

Data analysis

Table A1 shows the work summarized by Alesina et al. (2003),

which this paper will use in the research. This paper will use the

concept of ‘Cultural Fractionalization’ to measure this concept. To

obtain the basic value of how each country is diversified, this article

will simply add up the fractionalization index.

However, by simply adding them up, this article concludes as a

priori that the three contribute only and equally to the diversity of

culture, which this research cannot prove whether it is true or not.

‘Cultural Fractionalization’ is an ‘untouchable’ index without tools to

approach it. However, it can be argued that the concept of ‘Culture

Fractionalization’ is simply a result of mathematical calculation rather

than an index representing status of society, which would avoid the

criticism from empirical research. The result of the calculation of

‘Culture Fractionalization’ is presented in Table A2. This research will

continue further research based on such calculations.

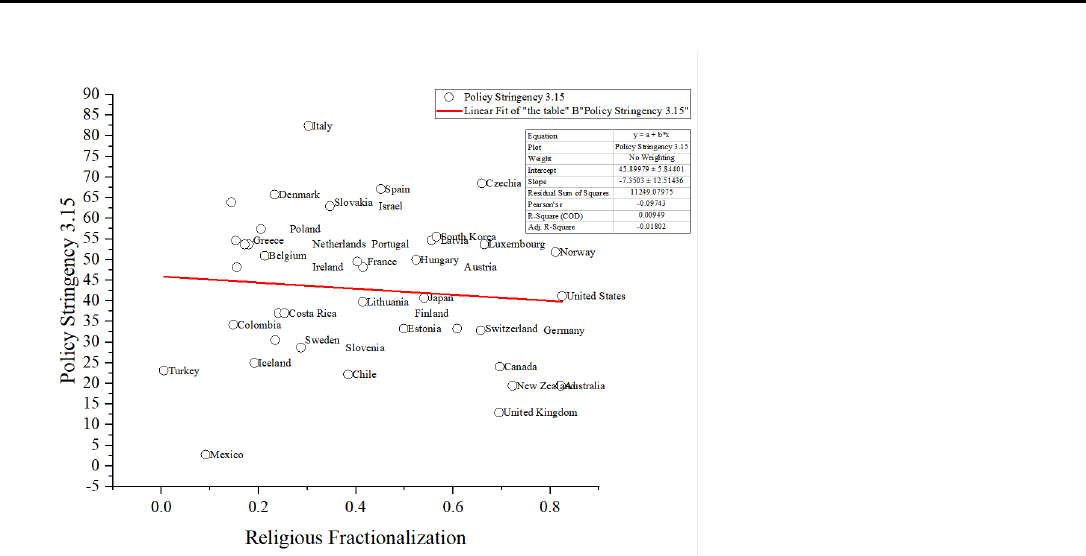

The figure is presented at the end of the document, showing the

relationship between the policy stringency index and four different

fractionalizations linear fitting results. The graph of the result is

presented in Figure A1, Figure A2, Figure A3, and Figure A4. All four

different linear fitting results have a negative slope from the calculation,

but the slope of the linear fitting result in each figure is slightly

different. The attribute of the linear fitting result are presented in the

up-right table of each figure, including slope and R-square, which are

both important for further discussion. The data will be discussed in

the next section.

Fall 2023

12

Discussion

As the analysis above shows, all four relations indicate a negative

correlation between policy stringency and fractionalization. While this

correlation may not be immediately apparent, the linear fitting result

reveals the underlying tendency that may not be easily discernible.

From the analysis, it can be seen that as cultural fractionalization

increases, countries tend to choose a looser policy response, and as

cultural fractionalization decreases, countries tend to choose the

opposite.

Some may argue that the tendency should not be taken seriously

if the slope of the linear fitting result is not steep enough to ensure

that the two variables are truly connected. However, the first point to

refute this argument would be that this research used a large group of

data. This article chose a large group of countries in order to reduce

error, and if all four figures indicate the same trend, it can further be

argued that this should not be a coincidence due to the repetition.

The second point is that the selection of different counties may

be little related to the final result. Different countries may have very

different fractionalization indices across linguistics, religion, and

ethnicity. A country may be highly diversified ethnically, but

homogeneous in language, or vice versa, but the fitting result remains

unchanged. If a country is culturally fractionalized, it may not be

fractionalized in ethnicity or language, or religion, which makes it

unrelated to the country selected for this research. Every country

differs in its contributions to the four fractionalization indices, but the

output is the same - all four show a negative correlation, which means

the final result cannot be changed.

Policy stringency may be most closely connected with linguistic

diversity within countries because, in all four graphics, the slope of

linear fitting result of linguistic diversity and policy stringency is the

steepest. This could be explained by the fact that all policies require

language to propagate, and a more fractionalized country makes this

process more difficult. Different linguistic groups may require

additional translation for certain policies to be effective, which would

Critique: a worldwide student journal of politics

delay the propagation process. Religious fractionalization is the least

relevant to policy stringency because the linear result is nearly flat. This

can be explained by the fact that policy nowadays has little connection

with religion. Religion may play a more indirect role in policy decisions

in response to the COVID-19 crisis by affecting other factors in society,

such as the strength of conservative forces.

The article would like to conclude its deduction in the following

two parts. The first dimension this article to consider is interpersonal

trust. Previous research identified a social factor influencing the

decision-making process during the pandemic, which includes trust in

government and interpersonal trust (Toshkov and Yesilkagit 2021).

These studies conclude that this trust can help government be more

confident in making tougher restrictive policies, which could also help

explain the negative correlation in the findings. People from different

ethnic groups may not tend to trust each other as much as those from

the same ethnic group, religion, or language. This dimension would

take interpersonal trust as the key factor in explaining the negative

correlation in the findings. The distrust may emerge from a person’s

deepest fear of the unknown, but if one is aware that the other person

shares the same cultural background, it would reduce the fear of the

unknown. Between different cultural groups, this research believes that

distrust could occur and be sensed by people, which would hinder

confidence in adopting policies. High-trust societies would have

enforced and endorsed tougher restrictive measures. Interpersonal

trust is a matter of ‘idea down’, it is common knowledge people within

a country would have shared. Once such common knowledge of trust

is formed, it would not change easily.

The other dimension to consider is how shared ideas are

determined by political ideologies, which is another factor that

thoroughly constituted by shared ideas among individuals. This

ideology would affect both immigration policy and policy response to

the COVID-19 crisis - looser immigration policy allows in residents

from other cultural groups and increase their cultural fractionalization.

In conclusion, it is not the fractionalization itself conduce to the loose

policy during the pandemic, but both of them are attributed to the

ideology of the government. A government that shares a looser culture

in adopting measures of policy measures would choose a looser policy

on both immigration policy and restrictive measures, resulting in the

Fall 2023

14

tendency the research has found. Ideology is another constituted idea

among actors, and it would further instruct how an actor will act.

There are a multitude of factors that could potentially impact the

relationship between cultural fractionalization and policy stringency.

However, in the current analysis, I have only focused on two key

dimensions: interpersonal trust and political ideology. These were

chosen because they were considered to be the most relevant and had

a logical connection to the main research question. Other factors, such

as economic conditions, demographic characteristics, or historical

context, were not included in the analysis because they did not fit well

within the logical framework of the study.

It is possible that these other factors could have an impact on the

relationship between cultural fractionalization and policy stringency,

but they were not considered in this analysis because they were not

deemed to be as relevant or important. Additionally, there may be other

factors that have not been identified or analysed in this study, and it is

possible that these could also have an impact on the relationship

between cultural fractionalization and policy stringency. However,

given the complexity of the research question and the limited scope of

this analysis, it was necessary to focus on a smaller set of factors and

exclude others.

In conclusion, the current analysis has provided some insights

into the relationship between cultural fractionalization and policy

stringency, but it is important to recognize that there may be other

factors at play that have not been considered in this study. Further

research is needed to fully understand the mechanisms that drive this

relationship and to identify any additional factors that may be relevant.

So, it is crucial to continue to explore and analyse this relationship in

order to gain a more complete understanding of the factors that

influence policy making in culturally diverse societies.

However, the discussions made above are only hypotheses, this

research has only revealed a possibility of explaining the result based

on basic logic, which still awaits further systemic research.

Critique: a worldwide student journal of politics

Conclusion

This study uncovers the inner connection between cultural

fractionalization and policy response to the COVID-19 virus. Most

previous studies neglect the impact culture has on policy decisions

during the pandemic. The research compared previous data calculated

on pandemic policy stringency and work done by Alesina et al. (2003)

on the fractionalization of different countries. This article has chosen

March 15

th

in this research to inspect different policy responses among

38 countries that entered the OECD, which would hopefully represent

the rest of the world and provide trustworthy data on their cultural

links. To choose an early stage of the crisis, this article aimed to state

their autonomous response rather than stimulate each other’s action.

By comparing 38 countries across four variables and their policy

stringency, this article found an inconspicuous negative correlation

between cultural fractionalization and policy stringency, wherein

cultural diversity rises, stringency declines.

Though the tendency is inconspicuous, this article tried to argue

that the phenomenon itself is not a coincidence because it is unrelated

to what and how many countries this article chooses, but an implicit

relation the research has revealed. After such a phenomenon is

confirmed, this article tried to explain the such matter by two possible

logics with a constructivist flavor. The first is interpersonal trust, which

may be lacking in a fractionalized society, and will eventually reduce

confidence in restrictive policy announcements. The second is ideology,

a compact style of policy-making that would affect both immigration

and restriction measures in the pandemic crisis.

Some questions may be asked to inspire further research on this

problem. The first problem is why some country, like the UK, are

limited in language and ethnicity but diversified in religion, yet they

have adopted a rather looser restrictive policy response. Those

countries may be diversified in one or two domains, but narrowed in

the rest, and whether they hold a looser or stricter policy, they will all

be a problem for the study, which may still await further investigation

into what happens in those countries. Another question is that this

short research lacks a discussion on exceptions. To explain exceptions,

the research needs to take a closer look at their domestic situation,

which may be a deviation since the topic focus on general tendency

only. Exceptions such as Canada, Iceland, and Czech could be due to

Fall 2023

16

the disease in their counties wasn’t severe in mid-March, but

researchers still need to carefully investigate such matters. The last

question would be the causal relationship between immigration policy

and restrictive policy during the pandemic. This paper conjectures that

both of them are influenced by a bigger concept, ‘political ideology’;

however, the restrictive policy could be directly influenced by

immigration policy, which is the core reason for cultural relations

within countries.

To study the policy response during the pandemic, scholars would

be benefits not only from one temporary crisis, but would also reveal

basic knowledge in policymaking. Though some of the hypothesis in

this paper still awaits further verification, the tendency the paper found

could be well enlightening.

References

Alesina, Alberto. Devleeschauwer, Arnaud. Easterly, William. Kurlat,

Sergio. Wacziarg, Romain. 2003. “Fractionalization”. Journal of

Economic Growth 8 (2): 155–94.

Allam, Zaheer. 2020. Surveying the COVID-19 pandemic and its

implications: urban health, data technology, and political economy, Victoria:

Elsevier.

Åslund, Anders. 2020. “Responses to the COVID-19 crisis in Russia,

Ukraine, and Belarus. Eurasian Geography and Economics”, Eurasian

Geography and Economics 61 (4–5): 532–45.

Benton, Meghan. Batalova, Jeanne. Davidoff-Gore, Samuel. Schmidt,

Timo. 2021. “COVID-19 and the State of Global Mobility in 2020.”

Migration Policy Institute. Available at: https://www.migrationpolicy.org

/research/covid-19-state-global-mobility-2020

Brown, Lauren. Horvath, Laszlo. Stevens, Daniel. 2021. “Moonshots

or a cautious take-off? How the Big Five leadership traits predict

Critique: a worldwide student journal of politics

Covid-19 policy response.” Journal of Elections, Public Opinion and Parties

31 (1): 335–47.

Burdge, Rabel J. 1996. “Introduction: Cultural diversity in natural

resource use.” Society and Natural Resources 9 (1): 1–2.

Capano, Giliberto. Howlett, Michael. Jarvis, Darryl. S. L. Ramesh, M.

Goyal, Nihit. 2020. “Mobilizing Policy (In)Capacity to Fight COVID-

19: Understanding Variations in State Responses.” Policy and Society 39

(3): 285–308.

Adam David. 2020. “Special report: The simulations driving the

world’s response to COVID-19.” Nature. April 2.

Flood, Colleen. M. MacDonnell, Vanessa. Philpott, Jane. Thériault,

Sophie. Venkatapuram, Sridhar. 2020. Vulnerable. Ottawa: University

of Ottawa Press.

George H. Mead. 1972. Mind, Self, and Society. Chicago: University of

Chicago Press.

Goyal, Nihit. and Howlett, Michael. 2021. “‘Measuring the Mix’ of

Policy Responses to COVID-19: Comparative Policy Analysis Using

Topic Modelling.” Journal of Comparative Policy Analysis: Research and

Practice 23 (2): 250–61.

Hale, Thomas. Angrist, Noam. Goldszmidt, Rafael. Kira, Beatriz.

Petherick, Anna. Phillips, Toby. Webster, Samuel. Cameron-Blake,

Emily. Hallas, Laura. Majumdar, Saptarshi. Tatlow, Helen. 2021. “A

global panel database of pandemic policies (Oxford COVID-19

Government Response Tracker).” Nature Human Behaviour 5 (4): 529–

38.

Hall, Peter A. Rosemary Taylor, R. C. Bates, R. 1996. “Political

Science and the Three New Institutionalisms.” Political Studies 44 (4):

936-57.

Havidan Rodriguez, Enrico L. Quarantelli, Russell Dynes. 2007.

Fall 2023

18

Handbook of Disaster Research. New York: Springer.

Boin, Arjen. Hart, Paul ’t. Stern, Eric. Sundelius, Bengt. 2007. “The

Politics of Crisis Management: Public Leadership Under Pressure.”

International Public Management Journal 10 (1): 111–7.

Lupien, Pascal. Rincón, Adriana. Carrera, Francisco. Lagos, Germán.

2021. “Early COVID-19 policy responses in Latin America: a

comparative analysis of social protection and health policy.” Canadian

Journal of Latin American and Caribbean Studies 46 (2): 297–317.

Maor, Moshe. Howlett, Michael. 2020. “Explaining variations in state

COVID-19 responses: psychological, institutional, and strategic

factors in governance and public policy-making.” Policy Design and

Practice 3 (3): 228–41.

Murphy, Peter. 2020. COVID-19 Proportionality, Public Policy and Social

Distancing. Singapore: Palgrave MacMillan.

Patsiurko, Natalka. Campbell, John L. Hall, John A. 2011. “Measuring

cultural diversity: ethnic, linguistic and religious fractionalization in

the OECD.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 35 (2): 195–217.

Peters, B. Guy. 1999. Institutional theory in political science: the new

institutionalism. New York: Pinter.

Serafini, Paula. Novosel, Noelia. 2020. “Culture as care: Argentina’s

cultural policy response to Covid-19.” Cultural Trends 30 (1): 52–62.

Sun, Bindong. Zhu, Pan. Li, Wan. 2019. “Cultural diversity and new

firm formation in China.” Regional Studies 53 (10): 1371–84.

Toshkov, Dimiter. Carroll, Brendan. Yesilkagit, Kutsal. 2021.

“Government capacity, societal trust or party preferences: what

Critique: a worldwide student journal of politics

accounts for the variety of national policy responses to the COVID-

19 pandemic in Europe?” Journal of European Public Policy 29 (7): 1–20.

Ramraj, Victor V. 2021. Covid-19 in Asia: Law and Policy Context. New

York: Oxford University Press.

Watkins, John P. 2021. “The Policy Response to COVID-19: The

Implementation of Modern Monetary Theory.” Journal of Economic

Issues 55 (2): 484–91.

Wendt, Alexander. 1999. Social Theory of International Politics.

Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Appendix A

Table A1. Ethnic, linguistic, and religious fractionalization.

Country

Ethnic

Linguistic

Religious

Australia

0.0929

0.3349

0.8211

Austria

0.1068

0.1522

0.4146

Belgium

0.5554

0.5409

0.2127

Canada

0.7124

0.5772

0.6958

Czechia

0.3222

0.3233

0.6591

Denmark

0.0819

0.1049

0.2333

Finland

0.1315

0.1412

0.2531

France

0.1032

0.1221

0.4029

Germany

0.1682

0.1642

0.6571

Greece

0.1576

0.03

0.153

Hungary

0.1522

0.0297

0.5244

Iceland

0.0798

0.082

0.1913

Ireland

0.1206

0.0312

0.155

Italy

0.1145

0.1147

0.3027

Japan

0.0119

0.0178

0.5406

Luxembourg

0.5302

0.0021

0.6644

Mexico

0.5418

0.644

0.0911

Netherlands

0.1054

0.1511

0.1796

Fall 2023

20

New Zealand

0.3969

0.5143

0.722

Norway

0.0586

0.1657

0.811

Poland

0.1183

0.0673

0.2048

Portugal

0.0468

0.0468

0.1712

Slovakia

0.2539

0.0198

0.1438

South Korea

0.002

0.2551

0.5655

Spain

0.4165

0.4132

0.4514

Sweden

0.06

0.1968

0.2342

Switzerland

0.5314

0.5441

0.6083

Turkey

0.32

0.2216

0.0049

UK

0.1211

0.0532

0.6944

United States

0.4901

0.2514

0.8241

Source: Alesina et al. 2003

Critique: a worldwide student journal of politics

Table A2. The calculation of ‘Culture Fractionalization’ and policy

stringency among 30 countries (March 2020)

Country

Cultural

Fractionalization

Policy

Stringency

Australia

1.2489

19.44

Austria

0.6736

48.15

Belgium

1.309

50.93

Canada

1.9854

24.07

Czechia

1.3046

68.52

Denmark

0.4201

65.74

Finland

0.5258

37.04

France

0.6282

49.54

Germany

0.9895

32.87

Greece

0.3406

54.63

Hungary

0.7063

50

Iceland

0.3531

25

Ireland

0.3068

48.15

Italy

0.5319

82.41

Japan

0.5703

40.74

Luxembourg

1.1927

53.7

Mexico

1.2769

2.78

Netherlands

0.4361

53.7

New Zealand

1.6332

19.44

Norway

1.0353

51.85

Poland

0.3904

57.41

Portugal

0.3904

53.7

Slovakia

0.2648

63.89

South Korea

0.4175

55.56

Spain

0.8226

67.13

Sweden

1.2811

30.56

Switzerland

0.491

33.33

Turkey

1.6838

23.15

United Kingdom

0.5465

12.96

United States

0.8687

41.2

Source: OurWorldinData.org

Critique: a worldwide student journal of politics

Figure A1. Ethnic fractionalization and policy stringency

Critique: a worldwide student journal of politics

Figure A2. Linguistic fractionalization and policy stringency

Fall 2023

24

Figure A3. Religious fractionalization and policy stringency

Critique: a worldwide student journal of politics

Figure A4. Cultural fractionalization and policy stringency