A National Council for the

Social Studies Publication

Number 49 • January/February 2014

www.socialstudies.org

Also: The Journal of an Underground Railroad Conductor

CARVED IN STONECARVED IN STONE

The Preamble to the Constitution

Middle Level Learning 49, p. M2

©2014 National Council for the Social Studies

2 January/February 2014

Carved in Stone:

The Preamble to the Constitution

Steven S. Lapham

Give your students HANDOUT 1 (on pages 5 and 6) showing photos of six friezes—bas-reliefs sculpted in stone. Ask three questions

of the class. Can students guess:

* When were these friezes made?

* In what country they are located?

* What are the adults and children (depicted in stone) doing?

Can students give intelligent reasons for their guesses? In other

words, what clues (details) are they looking at? What other

images or monuments or icons are they reminded of? What

inferences are they making?

These friezes (pronounced “freezes”) are especially American, as

they illustrate phrases from the Preamble to the U.S. Constitution.

Tell your students,

“In 1937, the Works Progress Administration (WPA) commissioned

artist Lenore Thomas to create some sculptures for the planned

community of Greenbelt, Maryland. Part of her work consisted

of these bas-relief friezes on the side of the Greenbelt Center

Elementary School. It’s a sturdy brick building that now serves

as the Greenbelt Community Center. The friezes are made of

Indiana limestone, and the name of this series is Preamble to

the Constitution.

“If you visit Greenbelt, Maryland, you’ll see that each frieze

has a phrase carved below it. On your handout, however, these

captions are missing.”

Matching Images with Words

Now that your students know when and where this art was

created, give them a copy of the Preamble on HANDOUT 2

(page 7) and ask them to work individually and quietly, matching

each frieze (labeled A-F, on HANDOUT 1) with a phrase (labeled

1–6, on HANDOUT 2) of the Preamble.

* What phrase from the Preamble belongs with each frieze? What’s

your guess?

For example, does frieze (A) go best with phrase 1, or phrase

2, 3, 4, 5, or 6? Each student should establish a one-to-one

correspondence between friezes and phrases. In other words,

each frieze gets only one, “best” caption.

Recording a Vote

After students have worked quietly for five minutes, address

the whole class, taking a vote on each image.

* How did your peers match up words with images? Let’s take a vote.

Each student can tally the votes using the grid on HANDOUT 3

(page 8) as you record the same information up on the board,

using a similar grid. How many students thought that frieze

(A) goes best with phrase 1? With phrase 2? (etc. up to phrase

6.) Record their choices for frieze (A) in the first column of

Handout 2, then move on to the next frieze, (B), etc.

ON THE COVER: A detail of the frieze “Insure Domestic Tranquility”

from the series Preamble to the Constitution carved by Lenore

Thomas for the Works Progress Administration in Greenbelt,

Maryland, 1937. Visit wpatoday.org/Greenbelt.html for more

Greenbelt history and images of Thomas’s sculptures.

Middle Level Learning 49, p. M3

©2014 National Council for the Social Studies

3 January/February 2014

Verifying the Vote

If there are inconsistencies with the counting of the vote, this is

also of interest, and worth spending some time to investigate.

The process of voting seems simple at first, but it is not at all

simple.

* Was the voting fair and accurate?

For example, are the totals at the bottom of each column equal?

They should be. If not, how might the class determine what

went wrong? For example, did one student mistakenly match

the same phrase with two different friezes? (i.e., Did someone

“violate” the one-to-one correspondence “rule”?) How would you

determine that error? Even in a simple exercise like this, it may

not be easy to keep an accurate and reliable count of a vote.

You could ask your students to create a ballot that would

minimize errors. What sort of paper ballot would create an

“audit trail” that might provide evidence of whether or how

an error has occurred during a vote? Could a paper “audit trail”

possibly permit a recount and correction “after the polls close?”

Exploring the Meaning

When the voting has concluded, discuss the results. If the

voting revealed a great diversity of opinions about the pairing

a particular frieze with a phrase, then ask students to explain

which details of the sculpture they are looking at, and what they

think these clues might mean. For example, frieze C—in which

some figures are holding flowers, shovels, and wheelbarrows—

might be illustrating the concepts of “domestic tranquility,”

or “the general welfare,” or “a more perfect union.”

1

Which

details did students emphasize as they decided on the “best”

pairings? (Which details had the most salience for the youth

in your classroom?)

* Is it okay if a work of art contains some ambiguities?

* Is it okay if different individuals interpret a work of art differently?

Are students comfortable with the fact that some friezes could

serve to illustrate more than one concept? Each limestone frieze

actually does have a caption carved below it, but a person

could argue that there is no “absolutely correct” way to vote

on several of the friezes. Here is the key, matching images (on

HANDOUT 1) with their “captions” carved in stone, which are

phrases from the Preamble (as numbered on HANDOUT 2):

Students can view each frieze with its carved-in-stone caption

by visiting “Greenbelt: A New Deal Community” at wpatoday.

org/Greenbelt.html.

Placing Art in Historical Context

During the New Deal, the WPA provided jobs to thousands of

writers and artists who might otherwise have been trapped

in dire poverty. All across America, you can see their work

in public places like schools, libraries, city halls, and national

parks. On this project, sculptor Lenore Thomas was invited to

create any images that she wished for decorating the exterior

of this public school.

* Why might the sculptor have chosen to illustrate a preamble

to one of the nation’s founding documents?

What might this work of art have meant to the people in

Maryland in 1937, who were witnessing the worst economic

depression in U.S. history? What were they thinking about

the role of the federal government, of private industry, and of

citizens—the farmers, laborers, judges, soldiers, and teachers

depicted in these stone panels?

Creating New Art Today

If sculptor Lenore Thomas were alive today, would she create

these same images? How would your students, living in the

21st century, depict the concepts stated in the Preamble to

the Constitution?

* How would you illustrate a phrase from the Preamble?

Assign students to illustrate one phrase from the Preamble

for homework. Alternatively, ask teams of students to create a

graphic book together during one classroom period. Students

could title their co-illustrated books, “An Illustrated Preamble

to the U.S. Constitution.”

Bringing the Constitution to Life

Ask students, “Why have a preamble at all? Why not just list

the branches of government and the role that each plays, and

leave it at that?” In short,

* What’s the value of a preamble in a document?

Finally, the class can discuss to what degree the ideals in the

Preamble are being realized today.

* What does the Preamble mean for you today?

KEY

IMAGE PHRASE and NUMBER

A Insure domestic tranquility (4)

B Establish justice (3)

C Promote the general welfare (6)

D To form a more perfect union (2)

E We the people (1)

F Provide for the common defense (5)

Middle Level Learning 49, p. M4

©2014 National Council for the Social Studies

4 January/February 2014

Is the federal government doing its part to bring this “mission

statement for the nation” to life in your community? Are your

elected officials living up to their duties? It’s your government.

What are you doing, as a citizen, to create “a more perfect

union?”

Steven S. Lapham is the editor of Middle Level Learning. NCSS offices

in Silver Spring are about 10 miles from Greenbelt, Maryland.

Explaining the Preamble

We the People, of the United States

A small group of well-educated men drew up a new form of

government in 1789, but the rights of this republican govern-

ment belonged to the citizens. Over the decades, amend-

ments would widen the definition of who was included in

the phrase “We the People”—and expand the rights and

responsibilities of citizenship.

in Order to form a more perfect Union

This phrase conveys the hope that the new Constitution

would produce and uphold a better form of governance

than did the Articles of Confederation.

establish Justice

The reasons for revolution against England were still very

much in the minds of American citizens. Fair trade and fair

trial were paramount.

insure domestic Tranquility

Shays’ Rebellion—an uprising of Massachusetts’s farmers

against the repayment of war debts—was one reason the

Constitutional Convention was held. Citizens were very

concerned with the keeping of peace within our borders.

provide for the common defence

No one state had the military might to defend itself. They

would have to work together to defend the nation.

promote the general Welfare

Citizens’ well being would be taken care of to the best extent

possible by a federal government.

and secure the Blessings of Liberty to ourselves and

our Posterity

Americans had fought long and hard for freedom from a

tyrannical government that imposed unjust laws. As free

citizens, people can meet, discuss, debate, and vote for their

representatives, thus governing themselves.

do ordain and establish this Constitution for the United

States of America

We the People have made this government and given it

power. No other approval is needed.

Source:

Constitution for Kids,

const4kids.forums.commonground13.us/?p=19

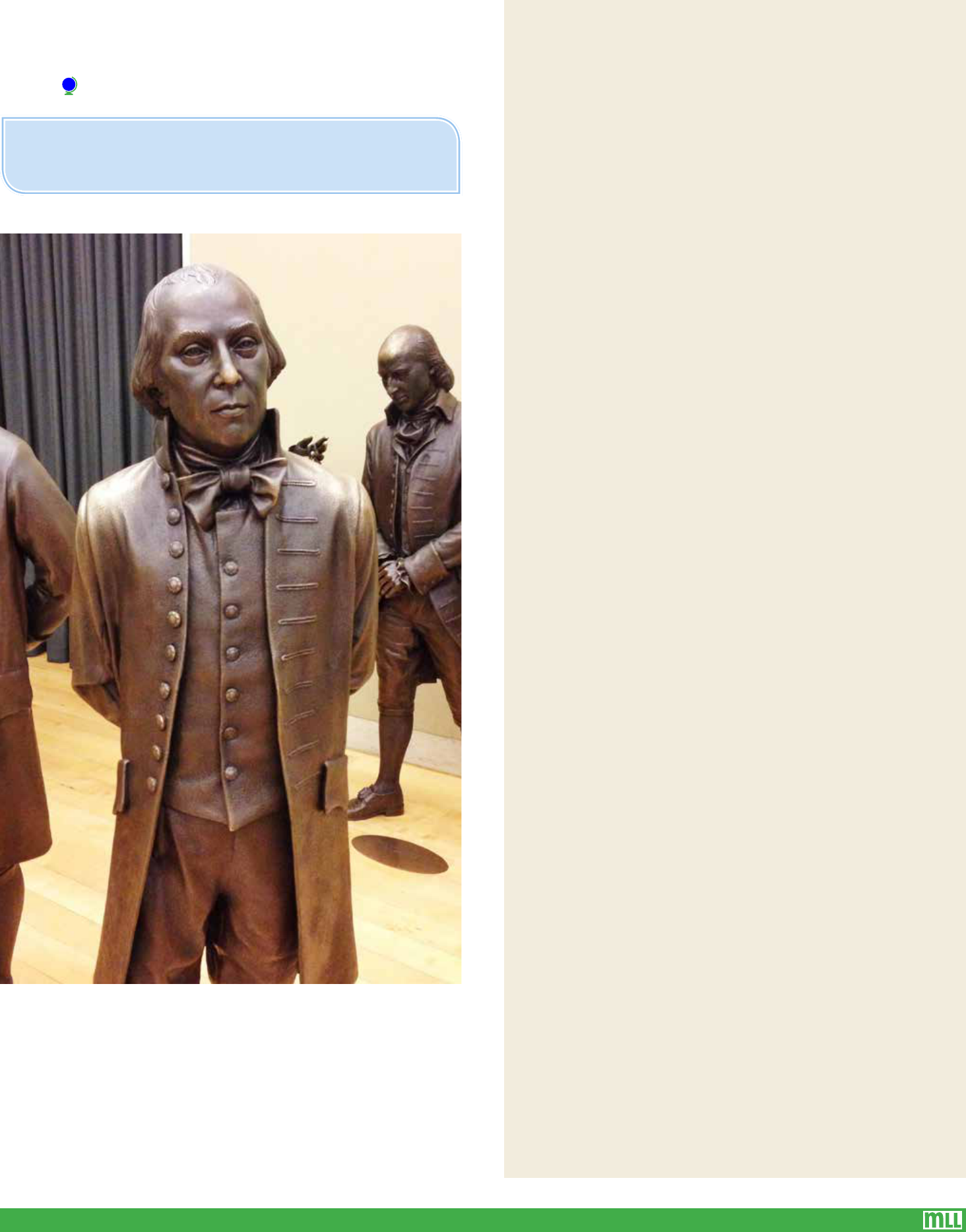

James Madison is known as the father of the Constitution because of his

pivotal role in the document’s drafting as well as its ratification. Madison

also drafted the first ten amendments—the Bill of Rights. This life-size

statue is in the National Constitution Center in Philadelphia.

Sources: “James Madison (1751–1836), constitutioncenter.org/learn/educational-

resources/founding-fathers/virginia#madison

“Who’s the Father of the Constitution?” at www.loc.gov/wiseguide/may05/

constitution.html.

Middle Level Learning 49, p. M5

©2014 National Council for the Social Studies

5 January/February 2014

Handout 1

Middle Level Learning 49, p. M6

©2014 National Council for the Social Studies

6 January/February 2014

Handout 1

Middle Level Learning 49, p. M7

©2014 National Council for the Social Studies

7 January/February 2014

Handout 2

PREAMBLE to the U.S. Constitution

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1787

PHRASE NUMBER

1 .....................................We the People of the United States,

2 ....................................................in Order to form a more perfect Union,

3 ....................................................establish Justice,

4 ....................................................insure domestic Tranquility,

5 ............................................ provide for the common defence,

6 ....................................................promote the general Welfare, and

secure the Blessings of Liberty to ourselves

and our Posterity, do ordain and establish this

Constitution for the United States of America.

NOTE: The lower case “d” and spelling of “defence” in the original 1787 Preamble is replicated here.

When carving the friezes and their captions in 1937, however, Lenore Thomas chose to use the American

spelling “defense,” as seen at

wpatoday.org/Greenbelt.html.

View the Constitution of the United States, the historical document, online at www.archives.gov/exhibits/charters/constitution.

html.

Middle Level Learning 49, p. M8

©2014 National Council for the Social Studies

8 January/February 2014

Handout 3

STUDENTS VOTE

Match Frieze with Phrase: Which frieze of the 1937 sculpture goes with which phrase of the Preamble?

To begin, match frieze A with phrase 1, or 2, or 3, … etc. up to 6. Then move on to frieze B, and match it

with a different. Use a hatch mark to mark your vote, like this / . Vote only once for each frieze and phrase.

When you are done, you will have voted six times, creating a one-to-one correspondence between images

and words.

Then tally how your classmates voted. For example, if eight students raise their hands to indicate that

frieze A goes with phrase 3, then you will mark eight hatch marks in that cell (row 3, column A), like this

///. And if five other students disagree and think that frieze A actually goes with phrase 6, then there will

be five hatch marks in that cell (row 6, column A). The total votes (the sum at the bottom of each column)

should equal the total number of students in the class, and should be the same for all six columns at the

close of voting. In other words, if there are 25 students in the class, the bottom row of cells should read

“25” all the way across when all votes are counted.

Frieze A–F

Phrases 1–6

A B C D E F

1

We the People

2

A More Perfect

Union

3

Justice

4

Tranquility

5

Defense

6

Welfare

TOTAL

VOTES

Middle Level Learning 49, p. M9

©2014 National Council for the Social Studies

9 January/February 2014

The Diary of an

Underground

Railroad Conductor

David Reader, Beth A. Twiss Houting,

and Rachel Moloshok

“No idea is more fundamental to Americans’ sense of ourselves as

individuals and as a nation than freedom. The central term in our

political vocabulary, freedom—or liberty, with which it is almost

always used interchangeably—is deeply embedded in the record

of our history and the language of everyday life.”

1

This quote from historian and author Eric Foner introduces the

website Preserving American Freedom, a digital history project

created by the Historical Society of Pennsylvania with the Bank

of America that explores the concept of freedom through 50

historic documents.

2

Some of these documents were created

when slavery was a legal institution in our nation, spanning

more than seven decades of U.S. history. In this article, we will

explore how students may use excerpts from one of these

documents—William Still’s “Journal C of Station No. 2” of the

Underground Railroad—to practice historical thinking skills

and meet the criteria of the Common Core standards.

A Conductor’s Responsibilities … and Risks

One of 18 siblings, William Still moved to Philadelphia in 1847

to become a clerk at the Pennsylvania Anti-Slavery Society

at the age of 20. His own mother had escaped slavery long

before he was born, and Still was keenly interested in abolition.

He gradually became more involved with the society, and

eventually served as its chairman.

Still had not received a formal education, but he advanced

his own reading and writing abilities greatly while working. In

1850, while listening to the life story of a former slave who was

seeking help from the society, Still realized that he was talking

to his long-lost brother. They shared specific details about their

mother that only a family member would know. Still decided

that he would preserve written records about fugitive slaves

so that members of other families might one day reunite with

one another.

William Still recorded details about nearly 900 fugitive slaves

whom he helped escape through the Underground Railroad in

Philadelphia. The risks of such an enterprise were great for Still

himself and for anyone mentioned in his journal. The Fugitive

Slave Act of 1850 called for punishments for any person who

aided an escaped slave or obstructed the “recovery” of the

escapee. Moreover, anyone who found Still’s elaborate notes

would learn the aliases, former owners, and routes of escape

of every fugitive who had passed through Philadelphia. That

information would compromise the safety of those listed in his

diary. Still understood these risks and kept his journal carefully

hidden for years.

Writing with an Eye toward History

When Still began recording the arrivals of fugitive slaves, he

likely believed that the institution of slavery would not end

in his lifetime, but he hoped that someday his diary would

be discovered. Thankfully, emancipation came, and in 1872,

Still was able to publish a book, The Underground Railroad,

drawing from the details in his journal. In some cases, Stills

was able to provide updates about how formerly enslaved

African Americans were living years after he had helped them

escape. Many of these former fugitives sent letters thanking

Still for his service.

The narratives and observations in Still’s book and journal

offer a fascinating perspective on slavery in the 1850s. Even

the short journal excerpt presented in this lesson demonstrates

a wide variety of experiences of enslavement and differing

Historical Society of Pennsylvania

Middle Level Learning 49, p. M10

©2014 National Council for the Social Studies

10 January/February 2014

motivations for seeking escape. The journal entries also hint at

how difficult it was to keep slave families together. Executing

an escape from slavery required incredible fortitude. Not only

did fugitives risk being captured and punished, but they often

faced the impossible decision of seeking their own freedom

at the expense of leaving children and spouses behind. To

travel in a large group, especially with children, increased the

chances of being caught. Still’s own mother made that painful

choice years before his birth, when she left behind two sons

in order to start a new life.

Examining the Evidence

The journal records, for each fugitive slave interviewed by Still,

a physical description, the person’s names and aliases, where

he or she had been enslaved, and an account of how he or she

was treated as a slave. The dehumanizing aspects of slavery

are evident. For example, on June 11, 1855, Still notes how one

man told him of the physical abuse his wife had suffered at the

hands of a slave master: “Flogging Females when stripped naked

was common with him.” Teachers wishing not to expose their

students to this passage (page 2 of the Still journal online) can

just use the handouts that follow in this article, which feature

different pages. Entries relate the abusive treatment slaves

experienced, the sorrows of families split apart by slave sales,

and the travails of escape and flight. Some accounts wryly note

the monetary “worth” that would be assigned to an individual

if he or she were sold or caught.

In contrast, the stories of hope and perseverance in the

face of suffering can elevate our opinions of humankind. For

example, Elias Jasper, who arrived from Newport, Virginia, on

June 22, 1855, was obviously a very talented person.

4

He had

learned many trades, including rope making, engineering, chair

making, and daguerreotyping, and was able to save some

money from being hired out. Though he had listened to the

Methodist minister preach obedience to the master, Jasper

could not “understand it.” He had been beaten and decided

to flee. He could not endanger his wife Mary by telling her,

however, and so left her behind.

Why do the two journal pages (reproduced on the Handout)

have a diagonal line drawn through them? Historians hypothesize

that as Still was writing the manuscript of “The Underground

Railroad” (1872)—drawing on the notes he had taken in Journal

C—he crossed out passages to keep track of his progress.

Historical Documents in Context

Teachers who visit the Preserving American Freedom website

will find other documents that give personal meaning to points

on the timeline of U.S. history, and that help place Still’s journal

in historical context. For example, the site features a copy of the

Emancipation Proclamation as well as a letter from Lieutenant

Nathaniel H. Edgerton, a white officer of a black regiment

during the Civil War, in which he praises the bravery of the

African American soldiers.

5

Still’s Journal C, the focus of this article, provides an

informational text for students to examine up close.

6

The material

in the journal covers most of the themes laid out in National

Curriculum Standards for Social Studies. The Underground

Railroad stands as an example of political and social organization

and power. The tensions wrought by economic and social

differences between North and South are revealed in day-by-

day lives of members of those societies. The personal struggles

of the African Americans, as recorded by William Still, help us

understand the challenges of individual development, of being

fully alive in that era—as well as in the present. These questions

are still valid today: Who or what is limiting my freedom? How

can I effectively resist, escape, outgrow, or overcome those

restrictions? And if I am free (as William Still was then), in a

society where others are struggling to find or express their

freedom, how do I respond to their struggle?

Notes

1. Eric Foner, “The Contested History of American Freedom,” in Preserving

American Freedom: The Evolution of American Liberties in Fifty Documents,

Historical Society of Pennsylvania,

digitalhistory.hsp.org/pafrm/section/

contested-history-american-freedom

.

2. The URL for the Preserving American Freedom website is

hsp.org/freedom

.

To go straight to the excerpt of Journal C discussed in this article, see

digitalhis-

tory.hsp.org/pafrm/doc/journalc

. To learn more about William Still or the

Historical Society of Pennsylvania’s digital history projects, visit

digitalhistory.

hsp.org.

3. “A contextual essay by historian Richard Newman may prove helpful to teach-

ers; see “Liberty, Slavery, and the Civil War,”

http://digitalhistory.hsp.org/

pafrm/essay/liberty-slavery-and-civil-war

. Other documents on the website

provide corroborating evidence about the effects of the institution of slavery,

such as the 1838 “Appeal of Forty Thousand Citizens, Threatened with

Disfranchisement, to the People of Pennsylvania,”

digitalhistory.hsp.org/

pafrm/doc/appeal

.

4. Lt. Edgerton’s letter is at

digitalhistory.hsp.org/pafrm/doc/edgerton

.

5. The images of William Still and the pages from his journal that appear on the

following handouts are courtesy of the Historical Society of Pennsylvania.

David Reader is a History Teacher at Camden Catholic High School in

Cherry Hill, New Jersey. He is a Freedom Teacher Fellow of the Historical

Society of Pennsylvania

Beth A. Twiss Houting is Senior Director of Programs and Services at

the Historical Society of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia

Rachel Moloshok is Manager of the Preserving American Freedom

Digital History Project at the Historical Society of Pennsylvania.”

Middle Level Learning 49, p. M11

©2014 National Council for the Social Studies

11 January/February 2014

SLAVERY in AMERICA

Teaching in Grades 5–8 with Middle Level Learning.

Lessons at www.socialstudies.org/publications/archive

Underground R.R. Journal, Number 49, January/February 2013

Harriet Tubman, Number 47, May/June 2013

Slavery AFTER the Civil War, Number 44, May/June 2012

Frederick Douglass and the Constitution, Number 33, September 2008

Venture Smith, Runaway, Number 28, January/February 2007

Philip Reid and Freedom, Number 24, September 2005

Runaway Ads, Number 20, May/June 2004

York, Lewis, and Clark, Number 19, January/February 2004

WPA Ex-Slave Narratives, Number 13, January/February 2002

Build a Freedom Train, Number 6, September 1999

Using the Handouts

Students can place the original, handwritten document in position A, the transcript of that text in position B, and commentary

on the text in position C. Reading the original script may be tough detective work for students, especially because students

are often not taught how to write in longhand, in this age of the computer keyboard. It will help students to read the transcript

first, or even the commentary, before tackling William Still’s handwriting.

A B C

Middle Level Learning 49, p. M12

©2014 National Council for the Social Studies

12 January/February 2014

Historical Society of Pennsylvania

Handout

Middle Level Learning 49, p. M13

©2014 National Council for the Social Studies

13 January/February 2014

TRANSCRIPT

(5)

June

22/

55

Arrived.

Wm Nelson

and

Susan his wife

,

and his son

Wm Thomas

; also

Louisa Bell

&

Ellias Jasper

, all arrived from Norfolk,

per

Capt. B.

Wm. is about 40, dark chesnut, medium

size, very intelligent, member of the

Methodist

Church

, under the charge of the Rev. Mr. Jones.

His owner’s name was Turner & Whitehead.

wh with whom he had served for 20

yr’s in the capasity of “

Packer

”. He had

been treated with mildness in some respects,

though had been very

tighly worked

, allowed

only $1.50 per week to board & clothe himself and family

upon. Consequently he was obliged to make

up the balance as he could. Had been

sold

once

one sister had been sold also. He was

prompted to escape because he wanted his

liberty was not satisfied with not having the

bl

priviledge of providing for his family,

His value $1000

. Paid

$240

for himself,

wife & child & Mrs Bell.

Susan is about 30,

dark, rather above medium size, well made

COMMENTARY ON THIS JOURNAL ENTRY

June was a mild month for travelling on foot. By 1855,

the debate over slavery in the United States was reaching

a fevered pitch.

A husband, wife, son, and two others escape from

Norfolk, Virginia, under the guidance of Underground

Railroad “Captain B,” whose name is kept secret (but

might be William B. Baylis).

Church membership is a “cultural signal,” hinting that

such a man probably avoids alcohol, fistfights, and

other popular vices of that era.

The job of “packer” likely involved handling shipping

crates in the warehouses and docks of Norfolk.

“Tightly worked”—closely and harshly supervised.

Breaking up families was a key part of the institution of

slavery, a way to keep people demoralized and helpless.

Wm. Nelson’s master did not provide clothes and food

to his slave. Nelson had to purchase necessities for

himself and his family with very little money.

One might expect $1,000 as the “value” for a skilled

slave.

Nelson paid Captain B a fee of $240 for his services

in leading the group to freedom.

Handout

Middle Level Learning 49, p. M14

©2014 National Council for the Social Studies

14 January/February 2014

Handout

Historical Society of Pennsylvania

Middle Level Learning 49, p. M15

©2014 National Council for the Social Studies

15 January/February 2014

[ The bracketed transcript appears on the next page of the journal, and is not shown in the handout at left. It completes the entry about Bell ].

TRANSCRIPT

good looking, intelligent &c, and a member

of the same church to which her husband belonged.

Was owned by Thos. Bottimore with whom

she had lived for 7 yr’s. Her treatment had been

a part of the time had been mild, the marriage

of her master however made a change, after-

ward

she had been treated badly

. Her master

to gratify his wife constantly threatening to

sell her. 4 of her Sisters had been sold

away

to parts unknown

years ago. Left

Father & mother, 3 Brothers & one sister.

Still in

Verginia

, living about 100 miles

from Norfolk. $1000 was the demand of the

owner for Susan &

her child 22 mos. old.

Louisa Bell is the

wife of

a free man.

is about 28 chesnut color,

good looking, intelligent, genteel, and a

member of no church. Was owned Stassen

by L. Stasson,

Confectioner.

[Her] lot had

been terrible on account of the continual

threats to sell her. Had once been sold,

had also had 5 sisters sold besides her

Mother. Th Louisa was oblige to leave

[two of her children behind. a boy 6 yrs & a

girl 2 ½ Yrs, The boys name was Robt. & the

girls Mary. Her husband, James Bell,

is to come on.]

COMMENTARY ON THIS JOURNAL ENTRY

The conditions of slave life could turn from mild to

harsh in a single day. Susan Nelson suffered when

her owner married a woman who was cruel to her.

When family members were sold, contact between

them was usually lost forever.

Journal author William Still is largely self-educated.

He spells “Virginia” incorrectly, but his writing is

clear, and most of the spelling is pretty good for that

historical period.

A mother and her infant or toddler, might—or might

not—be separated during a slave sale. Frederick

Douglass was separated from his mother shortly

after birth. She would walk miles in the dark to

visit her young son.

Marriages between free and enslaved blacks were not

uncommon. Louisa Bell, like Harriet Tubman, left

her free husband behind when she escaped slavery.

Bell also left her own children, but the writer hints

that Louisa hopes to be reunited with her husband

(and maybe children too) in the not-too-distant

future.

Louisa Bell’s owner was a candy-maker.

Handout

Middle Level Learning 49, p. M16

©2014 National Council for the Social Studies

16 January/February 2014

Middle Level Learning

Steven S. Lapham, MLL Editor • Michael Simpson, Director of Publications • Rich Palmer, Art Director

Greenbelt, MD: A Planned, New Deal Community

Created by President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s

Resettlement Administration, Greenbelt

was a part of a “green belt” town program.

Greenbelt was one of three; the other two

are Greenhills outside of Cincinnati, Ohio,

and Greendale, outside of Milwaukee,

Wisconsin. The three towns were

constructed to provide work relief for the

unemployed, provide affordable housing

for low income workers, and be a model for

future town planning in America. Visit

greenbeltmuseum.org/history, as well as

the Library of Congress, www.loc.gov/

pictures (search on the term “Greenbelt”)

to see photos of Greenbelt, Maryland.

First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt was a

strong advocate for this and other

resettlement programs and towns, such

as Arthurdale, West Virginia. Visit www.

gwu.edu/~erpapers/teachinger/glossary/

arthurdale.cfm.

Are you studying Hinduism this year? What might that

have to do with community planning? Think about it.

Three main Hindu deities (and the forces they command)

are Brahma (creation), Vishnu (preservation), and Shiva

(destruction). Now take a look around where you live:

• What parts of your neighborhood were carefully

planned before they were created? What things

were built without much planning? What occurred

randomly (like a crack in the sidewalk) or by a force

of nature (like a weedy acacia tree)?

• Now think about maintaining the things you see.

What objects need frequent service, repair, or refuel-

ing? What things or activities might be unsustainable?

What should be preserved, and how would you do

that?

• Finally, what objects ought to be demolished or

recycled? What will need replacing in five, or ten, or

twenty years? What might be “repurposed” (altered

and given a new use)?

Make a three-part list of how the “energies of the uni

-

verse” are at work in your neighborhood.