Essentials of Economics in Context – Sample Chapter for Early Release

DRAFT 1

CHAPTER 4: CONSUMPTION AND DECISION-MAKING

In Chapter 1, we defined economic actors, or economic agents, as people or organizations engaged

in any of the four essential economic activities: production, distribution, consumption, and

resource management. Economics is about how these actors behave and interact as they engage in

economic activities. We begin this chapter with a brief overview of the classical and neoclassical

perspectives on economic behavior. The rest of the chapter focuses specifically on consumer

behavior—how individuals make decisions on what goods and services to consume. We look at

both traditional and contemporary approaches to understanding consumer behavior.

1. HISTORICAL PERSPECTIVES ON ECONOMIC BEHAVIOR

Economics is a social science—it is about people and how we organize ourselves to meet our needs

and enhance our well-being. All economic outcomes are ultimately determined by human

behavior. Thus, economists have traditionally used as a starting point some kind of statement about

the motivations behind economic actions.

1.1 CLASSICAL ECONOMIC VIEWS OF HUMAN NATURE

The classical economic view of human behavior is largely based on the theoretical framework

presented in Adam Smith’s An Inquiry Into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations,

published in 1776. In this book, Smith suggests that an economic system based on markets can

effectively promote the general welfare of society. He reasoned that a businessman who is

interested in maximizing his own monetary gain would nonetheless serve the social good if the

best available means for his monetary gain was to produce high quality goods at a competitive

price.

The idea that self-interest can unintentionally promote the social good is an important and

valuable one. However, it has been often taken out of context to mean that if people only behave

with self-interest, they will also always do what is best for the entire society. This interpretation

would have astonished Smith, who, in his other famous book, The Theory of Moral Sentiments,

emphasized the desire of people to maintain their own self-respect and earn the respect of others.

He assumes that this desire motivates people to act honorably, justly, and with empathy for others

in their community. Smith recognized that self-interest is important, but he also believed that

narrow self-interest will be held in check by people’s “moral sentiments” (the universal desire for

self-respect and the respect of others). Thus Smith’s vision of human motivation was one in which

individual self-interest was mixed with social motives.

Smith was followed by other economists, such as David Ricardo, John Stuart Mill, and

Alfred Marshall, who held similarly complex views of human nature and thought quite deeply

about ethics. For example, Marshall viewed human motivations as being influenced by a desire to

improve the human condition. He specifically focused on the reduction of poverty so as to allow

people to develop their higher moral and intellectual faculties rather than being condemned to lives

of desperate effort for simple survival.

1.2 THE NEOCLASSICAL MODEL

Essentials of Economics in Context – Sample Chapter for Early Release

DRAFT 2

In the twentieth century, the neoclassical model came to dominate economic thinking. This

approach took a narrower and simpler view of human motivations. Recall from Chapter 2 that the

basic neoclassical model only considers two main types of economic actors—firms and

households. This model assumes that firms maximize their profits from producing and selling

goods and services, and households maximize their utility (or satisfaction) from consuming goods

and services. Economic actors are assumed to be self-interested and “rational,” meaning that

people generally make logical decisions that produce the best outcomes for themselves. Also, firms

and households are assumed to interact in perfectly competitive markets. In this model,

competition (rather than Smith’s “moral sentiments”) is regarded as the check on self-interested

behavior of individuals and firms. Competition is understood as being able to prevent firms from

charging too much for their product or producing poor-quality goods.

neoclassical model: a model that portrays the economy as composed of profit-maximizing

firms and utility-maximizing households interacting through perfectly competitive markets

Some benefits can be gained from looking at economic behavior in this way. The

assumptions reduce the actual (very complicated) economy to something that is much more limited

but also easier to analyze. With some additional assumptions, the model can be elegantly expressed

in figures, equations, and graphs. This traditional model is particularly well suited for analyzing

the determination of prices, the volume of trade, and economic efficiency in certain cases. We will

take a closer look at the neoclassical model of consumer behavior in Section 2.

Moving into the twenty-first century, most economists have accepted that human

motivations are much more complex. As we will see in Section 3, in recent years, economists have

devised many creative experiments to explore how people make actual economic decisions,

typically showing how context can influence decisions. While this model of economic behavior

can’t necessarily be summed up in tidy mathematical equations and graphs, it is more

comprehensive, and often more accurate, than the neoclassical model.

Discussion Questions

1. Discuss, with an example, how individuals acting in their own self-interest may sometimes

lead to outcomes that serve the social good.

2. Do you agree with the assumption of the neoclassical model that human behavior is rational

and self-interested? Can you think of some examples of economic behavior that might

contradict these assumptions?

2. THE NEOCLASSICAL THEORY OF CONSUMER BEHAVIOR

We start our analysis of consumption behavior with the neoclassical model. As mentioned

previously, this model is based on simplistic assumptions, but it provides some useful insights.

2.1 CONSUMER SOVEREIGNTY

Consumer sovereignty refers to the notion that satisfaction of consumers’ needs and wants is the

ultimate economic goal and that firms will always seek to organize their production solely in

response to better meeting consumer desires. For example, consider the increase in the sales of

Essentials of Economics in Context – Sample Chapter for Early Release

DRAFT 3

sport utility vehicles (SUVs) in the United States in recent decades. The theory of consumer

sovereignty would suggest that the primary reason for the growth of SUV sales is a change in

consumers’ preferences for larger vehicles over cars. Consumer sovereignty stands in direct

contrast to the idea that some firms can manipulate consumer desires through advertising or that

some firms might be largely unresponsive to what consumers actually want.

consumer sovereignty: the idea that consumers’ needs and wants determine the shape of

all economic activities

2.2 THE BUDGET LINE

Consumers are constrained in their spending by the amount of their total budget. We can represent

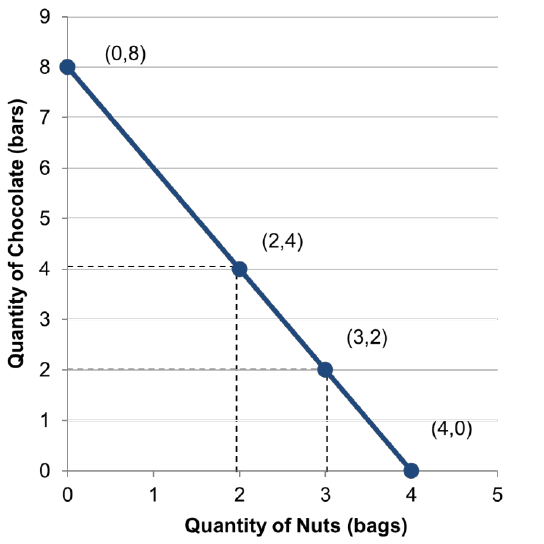

this in a simple model in which consumers have only two goods from which to choose. In Figure

4.1 we present a budget line, which shows the combinations of two goods—chocolate bars and

bags of nuts—that a consumer can purchase. In this example, our consumer—let’s call him

Quong—has a budget of $8. The price of chocolate bars is $1 each, and nuts sell for $2 per bag.

budget line: a line showing the possible combinations of two goods that a consumer can

purchase

Figure 4.1 The Budget Line

If Quong spends his $8 only on chocolate, he can buy 8 bars, as indicated by the point

where the budget line touches the vertical axis. If he buys only nuts, he can buy 4 bags, as indicated

by the (4, 0) point on the horizontal axis. He can also buy any combination in between. For

example, the point (2, 4), which indicates 2 bags of nuts and 4 chocolate bars, is also achievable.

Essentials of Economics in Context – Sample Chapter for Early Release

DRAFT 4

This is because (2 × $2) + (4 × $1) = $8. (Note that to keep things simple we assume that Quong

can buy only whole bars and whole bags, not fractions of them—for example, he can’t buy 2.5

bars of chocolate. However, we draw the budget line as continuous to reflect the more general case

with many more alternatives.)

A budget line is similar to the concept of a production-possibilities frontier, which we

discussed in Chapter 1. A budget line defines the choices that are possible for Quong. Points above

and to the right of the budget line are not affordable. Points below and to the left of the budget line

are affordable but do not use up the total budget. This simple model assumes that people always

want more of at least one of the goods in question; hence, consuming below the budget line would

be inefficient. Therefore, a rational consumer will always choose to consume at a point on the

budget line.

The position of the budget line depends on the size of the total budget (income) and on the

prices of the two goods. For example, if Quong has $10 to spend instead of $8, the line would shift

outward in a parallel manner, as shown in Figure 4.2. He could now consume more nuts, or more

chocolate, or a more generous combination of both.

Figure 4.2 Effect of an Increase in Income

A change in the price of one of the goods will cause the budget line to rotate around a point

on one of the axes. So if the price of nuts dropped to $1 per bag (and Quong’s income was again

$8), the budget line would rotate out, as shown in Figure 4.3. Now, if Quong bought only nuts, he

could buy 8 bags instead of 4. With the price of chocolate unchanged, however, he still could not

buy more than 8 chocolate bars.

Essentials of Economics in Context – Sample Chapter for Early Release

DRAFT 5

Figure 4.3 Effect of a Fall in the Price of One Good

Note that if both prices change, the budget line could shift in any direction, depending on

how the two prices changed. If both prices changed by the same percentage, then the new budget

line would be parallel to the original, similar to a change in income. Draw some graphs to prove

this to yourself.

A budget line tells us all the combinations of purchases that are possible. However, it does

not tell us which combination the consumer will choose. To get to this, we must add the theory of

utility.

2.3 CONSUMER UTILITY

The neoclassical model assumes that individuals have certain preferences (or tastes) for certain

goods and services. Consumers seek to satisfy these preferences and thereby derive utility, which

is defined as the pleasure or satisfaction received from consuming goods, services, or experiences.

Consumers cannot satisfy all their preferences because they are constrained by their budget, so

they have to think carefully about what goods to purchase in order to maximize the amount of

utility from their given budget.

utility: the level of usefulness or satisfaction gained from a particular activity, such as the

consumption of a good or service

Utility is a somewhat vague concept, like well-being, and cannot be measured

quantitatively in the real world. However, for the purposes of this model we assume that we can

measure utility in some imaginary unit of “satisfaction.” Table 4.1 presents the total utility that

Quong obtains from purchasing different quantities of chocolate bars in a given period, say a day.

Essentials of Economics in Context – Sample Chapter for Early Release

DRAFT 6

Table 4.1 Quong’s Utility From Consuming Chocolate Bars

We can then plot Quong’s total utility from consuming chocolate bars in Figure 4.4. This

relationship between utility and the quantity outlined in Figure 4.4 is an example of a utility

function, or a total utility curve.

utility function (or total utility curve): a curve showing the relation of utility levels to

consumption levels

Figure 4.4 Quong’s Utility Function for Chocolate Bars

Rather than just looking at total utility, economists tend to focus on how utility changes

from one level of consumption to another. The change in utility for a one-unit change in

consumption is known as marginal utility. The word “marginal” puts the focus on incremental

change rather than total change.

marginal utility: the change in a consumer’s utility when consumption of something

changes by one unit

We can determine Quong’s marginal utility by referring to Table 4.1. We see that Quong

obtains 10 units of “satisfaction” from consuming his first chocolate bar. When he eats an

Quantity of chocolate bars

Total utility

Marginal utility

0

0

—

1

10

10

2

18

8

3

24

6

4

28

4

5

30

2

6

29

−1

Essentials of Economics in Context – Sample Chapter for Early Release

DRAFT 7

additional chocolate bar, his total utility increases from 10 to 18 units (10 + 8 = 18). Here, his total

utility is the units of satisfaction obtained from consuming the two bars, while his marginal utility

from consuming the second chocolate bar is only 8 units. Consuming his third chocolate bar, he

obtains a marginal utility of 6 units. Total utility continues to increase, but in smaller installments

since the marginal utility is progressively decreasing. If marginal utility becomes negative, total

utility decreases.

Figure 4.4 provides a visual picture of how Quong’s utility curve levels off as his

consumption of chocolate bars increases. This is generally expected—that successive units of

something consumed provide less utility than the previous unit. In other words, consumers’ utility

functions generally display diminishing marginal utility. Notice that after six bars of chocolate

the marginal utility is negative. In other words, the sixth bar of chocolate has left Quong with

negative pleasure (i.e., pain). Perhaps that sixth bar of chocolate gave him an upset stomach.

diminishing marginal utility: the tendency for additional units of consumption to add less

to utility than did previous units of consumption

We can now apply the concept of utility to the budget line that Quong faces. Realize that

Quong will also have a utility function for bags of nuts, which will display a similar pattern of

diminishing marginal utility. Let’s assume that his first bag of nuts provides him with 20 units of

utility, his second bag with 15 additional units, and his third bag with 10 additional units (more

bags result in even fewer units of utility). How can Quong allocate his limited budget to provide

him with the highest amount of total utility?

We provide a formal model of utility maximization in an online Appendix to this chapter,

but using marginal thinking, we can easily see how Quong can approach his problem in a purely

rational manner. Suppose that Quong is thinking about how he will spend his first $2. With $2, he

can buy either two chocolate bars or one bag of nuts. If he buys two chocolate bars, he will obtain

18 total units of utility, as shown in Table 4.1. If he buys one bag of nuts instead, he will obtain 20

units of utility. Thus, Quong will receive greater utility by spending his first $2 on a bag of nuts.

What about his next $2? If he spends this on his second bag of nuts, he obtains an additional

15 units of utility. But if he instead purchases his first two chocolate bars, he will obtain 18 units

of utility. So, by spending his next $2 on chocolate bars, he increases his utility by a greater

amount. After spending $4, Quong has purchased one bag of nuts and two chocolate bars, thus

obtaining a total utility of 38 units. Quong can continue to apply marginal thinking to maximize

his utility until he has eventually spent his entire budget. (Test yourself: How will Quong spend

his third $2, by buying another bag of nuts or two more bars of chocolate?)

1

The basic decision

rule to maximize utility is to allocate each additional dollar on the good or service that provides

the greatest marginal utility for that dollar.

2

We suspect that you have never thought about how to spend your money in a manner

similar to Quong’s marginal analysis of chocolate and nuts. As we will see in the following

sections, people may not always act rationally by maximizing their utility, as suggested by the

neoclassical model. Additionally, this model does not tell us anything interesting about why

consumers make particular choices; that is, preferences are taken as given. The contemporary

models, which we discuss in the following sections, present a more realistic analysis of consumer

behavior by considering how preferences may be influenced by contextual factors.

Essentials of Economics in Context – Sample Chapter for Early Release

DRAFT 8

Discussion Questions

1. Budget lines can be used to analyze various kinds of tradeoffs. Suppose that you have a total

“time budget” for recreation of two hours. Think of two activities you might like to do for

recreation, and draw a budget line diagram illustrating the recreational opportunities open to

you. What if you had a time budget of three hours instead?

2. Explain in words why the total utility curve has the shape that it does in Figure 4.4.

3. MODERN PERSPECTIVES ON CONSUMER BEHAVIOR

Over the past few decades, the neoclassical view of human behavior is being increasingly replaced

by an alternative approach that is commonly called behavioral economics. Behavioral economics

gathers insights from numerous disciplines, including economics, psychology, sociology,

anthropology, neuroscience, and biology, to predict how people actually make decisions.

Behavioral economics tests theories by conducting experiments and gathering empirical evidence.

This work has proven valuable in explaining behavior that may appear to be irrational.

behavioral economics: a subfield of economics that uses insights from various social and

biological sciences to explore how people make actual economic decisions

3.1 BEHAVIORAL ECONOMICS AND RATIONALITY

Let us start by examining the neoclassical assumption that people are completely rational, meaning

they have all the information about the costs and benefits of every single choice available to them

and that they can accurately calculate the optimal choice that maximizes their utility. While it may

be possible to make a rational choice between a chocolate bar and a bag of nuts, as discussed in

the example previously, it becomes much more complicated when we are faced with a wide set of

choices. We may not have complete information about each choice. Furthermore, we may not even

be able to accurately process and weigh the information that we do possess.

Consider a famous experiment. Researchers at a supermarket in California set up a display

table with six different flavors of jam. Shoppers could taste any (or all) of the six flavors and

receive a discount coupon to purchase any flavor. About 30 percent of those who tried one or more

jams ended up buying some.

3

The researchers then repeated this experiment but instead offered 24

flavors of jam for tasting. In this case, only 3 percent of those who tasted a jam went on to buy

some. In theory, it would seem that more choice would increase the chances of finding a jam that

one really liked and would be willing to buy. But, instead, the additional choices decreased one’s

motivation to make a decision to buy a jam.

Because we often have trouble processing all the available information, we often employ

mental heuristics, which are rules of thumb or mental shortcuts that we use to make decisions.

While heuristics can often help us make quick and effective decisions, they can often lead to biases

based on people’s viewpoints or thinking process. Research by Nobel Laureate Daniel Kahneman

has found that people tend to give excessive weight to information that is easily available or vivid,

something he called the availability heuristic. For example, if you regularly watch crime shows

on television, you may over-rate the risk of being a victim of crime yourself.

heuristic: a rule of thumb or mental shortcut that we use to make decisions

Essentials of Economics in Context – Sample Chapter for Early Release

DRAFT 9

availability heuristic: placing undue importance on particular information because it is

readily available or vivid

Kahneman has also shown that the way a decision is presented to people can significantly

influence their choices, an effect he refers to as framing. For example, consider a gas station that

advertises a special 5-cent-per-gallon discount for paying cash. Meanwhile, another station with

the same price instead indicates that they charge a 5-cent-per-gallon surcharge to customers who

pay by credit card. Although the prices end up exactly the same, experiments suggest that

consumers respond more favorably to the station that advertises the apparent discount.

framing: changing the way a particular decision is presented to people in order to influence

their behavior

Advertisers and politicians have long been known to use framing techniques to influence

the behavior of consumers and voters. For example, beverage or automobile companies show their

products in beautiful natural settings or with beautiful female models to make the consumer feel

as if purchasing these products will bring the feelings of pleasure or well-being they may associate

with natural or human beauty. Similarly, politicians are also often adept at framing issues to trigger

emotions of greed or fear rather than offering sound information on which voters can make good

decisions.

An effect similar to framing is known as anchoring, in which people rely on a piece of

information that is not necessarily relevant as a reference point in making a decision. In one

powerful example, graduate students at the MIT Sloan School of Management were first asked to

write down the last two digits of their Social Security numbers. A short time later, they were asked

whether they would pay this amount, in dollars, for various products. The subjects with the highest

Social Security numbers indicated a willingness to pay about 300 percent more than those with the

lowest numbers! The students had unconsciously used their Social Security numbers as an

“anchor” in evaluating the worth of the products.

4

In a real-world example of anchoring, the

kitchen equipment company Williams Sonoma was able to increase the sales of its $279 bread

maker after it introduced a “deluxe” model for $429. The introduction of the deluxe model created

an anchoring effect that made the $279 bread maker seem like a relative bargain.

5

anchoring effect: overreliance on a piece of information that may or may not be relevant

as a reference point when making a decision

In some circumstances, people tend to go with the “default option” when presented with a

choice, even if the default option is not necessarily the rational choice. One classic example of the

power of defaults looks at whether people are registered to donate their organs at death.

6

In some

European countries, such as Austria, Belgium, and France, people are automatically registered as

organ donors, but can opt out if they choose to. In these countries, about 98–99 percent of people

stay registered. But in other European countries, such as Denmark, Germany, and the United

Kingdom, people must sign up to be organ donors. In other words, the default option is that they

are not registered. In these countries, less than 20 percent of people register to be organ donors.

Such cases, where people prefer things to stay the same by doing nothing or favor the option that

is familiar or expected, is referred to as status quo bias.

Essentials of Economics in Context – Sample Chapter for Early Release

DRAFT 10

status quo bias: a cognitive bias in favor of that which is familiar, expected, or automatic

3.2 THE ROLE OF TIME, EMOTIONS, AND OTHER INFLUENTIAL FACTORS

Much evidence suggests that people seem to place undue emphasis on gains or benefits received

today without considering the implications of their decisions for the future. A good example of

this is the large number of people who have acquired significant high-interest credit card debt due

to excessive spending. According to one study, about 6 percent of Americans are considered

“compulsive shoppers,” who seek instant gratification with little concern for the troublesome

consequences of running up a great deal of debt.

Economists say that someone who does not pay much attention to the future consequences

of his or her actions has a high time discount rate. This means that in his or her mind, future

events are heavily discounted when weighed against the pleasures of today. On the other hand,

people who have a low time discount rate would place more relevance on future consequences.

For example, people who invest in a college education have a relatively low time discount rate,

because they are willing to forgo current income or relaxation, and pay substantial tuition, to study

for some expected future gain. Various studies have shown how people who have high discount

rates are more likely to make seemingly irrational, or unhealthy choices inconsistent with their

long-term goals. A 2016 study reported that those with high time discount rates are consistently

found to be more likely to smoke, abuse alcohol, take illicit drugs, and engage in risky sexual

behaviors.

7

time discount rate: an economic concept describing the relative weighting of present

benefits or costs compared to future benefits or costs

The choices we make are also influenced by our emotions. The conventional view is that

emotions get in the way of good decision-making, as they tend to interfere with logical reasoning.

But again, research from behavioral economics suggests a more nuanced reality. It does not seem

to be true that decisions based on logical reasoning are always “better” than those based on emotion

or intuition. Instead, studies suggest that reasoning is most effective when used for making

relatively simple economic decisions, but for more complex decisions, we can become

overwhelmed by too much information. In such cases, emotions or intuition can sometimes help

us make better decisions.

8

For example, an experiment with college students involved their tasting five brands of

strawberry jam.

9

In one case, students simply ranked the jams from best to worst. The student

rankings were highly correlated with the results of independent testing by Consumer Reports,

suggesting that the students’ rankings were reasonable. But in another case, students were asked

to fill out a written questionnaire explaining their preferences. As a result of the additional

deliberation, students’ rankings were no longer significantly correlated with the Consumer Report

rankings. The researcher concluded that overthinking might cut individuals off from the wisdom

of their emotions, which are sometimes much better at assessing actual preferences.

10

Altruism, meaning a concern of the well-being of others without thought about oneself,

can also motivate our behavior. Although it would be idealistic to assume that altruism is the prime

mover in human behavior, it is reasonable to assert that some elements of altruism enter into most

people’s decision-making—contrary to the neoclassical assumption of rational, self-interested

individuals. Especially relevant to economics is the fact that much economic behavior may be

motivated by a desire to advance the common good—the general good of society, of which one’s

Essentials of Economics in Context – Sample Chapter for Early Release

DRAFT 11

own interests are only a part. People are often willing to participate in the creation of social

benefits, even if this involves some personal sacrifice, as long as they feel that others are also

contributing.

altruism: actions focused on the well-being of others, without thought about oneself

common good: the general well-being of society, including one’s own well-being

A well-functioning economy cannot rely only on self-interest. Without such values as

honesty, for example, even the simplest transaction would require costly and elaborate safeguards

or policing. Imagine if you were afraid to put down your money before having in your hands the

merchandise that you wished to purchase—and the merchant was afraid that as soon as you had

what you wanted, you would run out of the store without paying. Such a situation would require

police in every store—but what if the police themselves were unethical? Without ethical values

that promote trust, inefficiencies would overwhelm any economic system. Fortunately, behavioral

economics experiments demonstrate that people really do pay attention to social norms, even when

this has a cost in terms of their narrow self-interest, as discussed in Box 4.1.

BOX 4.1 THE ULTIMATUM GAME

The “Ultimatum Game” is a behavioral economics experiment in which two people are told

that they will be given a sum of money, say $20, to share. The first person gets to propose a

way of splitting the sum. This person may offer to give $10 to the second person, or only $8,

or $1, and keep the rest. The second person cannot offer any input to this decision but has the

power to decide whether to accept the offer or reject it. If the second person rejects the offer,

both people will walk away empty-handed. If the offer is accepted, they get the money and

split it as the first person indicated.

If the two individuals act only from narrow financial self-interest, then the first person

should offer the second person the smallest possible amount—say $1—in order to keep the

most for himself or herself. The second person should accept this offer because, from the point

of view of pure financial self-interest, $1 is better than nothing.

Contrary to such predictions, researchers find that deals that vary too far from a 50–50

split tend to be rejected. Specifically, offers of around 40 percent or more are almost always

accepted, while offers of 20 percent or less are almost always rejected.

11

People would rather

walk away with nothing than be treated in a way that they perceive as unfair. Also, whether

out of a sense of fairness or a fear of rejection, individuals who propose a split often offer

something close to 50–50. Such behavior suggests we have cooperative inclinations along with

our more self-interested inclinations.

Other recent evidence suggests that pursuing pure self-interest does not lead to happiness.

A 2017 journal article by economist Tom Lane reviewed dozens of studies that looked at the

relationship between happiness levels and economic behavior and concluded that: “happiness

tends to result from pro-social behavior,” including trust and generosity.

12

Meanwhile, there “is

clear evidence of a negative relationship between happiness and selfishness.” These results

Essentials of Economics in Context – Sample Chapter for Early Release

DRAFT 12

indicate that if one wants to be happy in life, being trustful and generous might be more “rational”

than being selfish.

Finally, our brains, physiology, and genetics also play a role in influencing our decision-

making. Referred to as neuroeconomics, this relatively new interdisciplinary field is based on

approaches, such as using brain imaging, or a functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI)

machine, to study the brain and predict human behavior. For example, one research study that used

an fMRI machine to study the brain confirms the findings discussed previously—that when people

engage in cooperative behavior, regions of the brain associated with positive emotions are

activated.

13

On the other hand, when observing others being treated unfairly, our brains react as if

we ourselves had been treated unfairly.

14

neuroeconomics: the interdisciplinary field that studies the role our brains, physiology,

and genetics play in how we make economic decisions

Now that we have considered several factors influencing economic behavior, we can

present a model based on behavioral economics using concepts that have been suggested as

alternatives to self-interested and rational behavior.

3.3 CONSUMER BEHAVIOR IN CONTEXTUAL ECONOMICS

Recent research has generally refuted the neoclassical view of self-interested people making

economic decisions that maximize their utility (or profits, in the case of businesses). We now use

the lessons from the previous discussion to develop a more modern and accurate model of

consumer behavior.

One important factor in an economic model of behavior is information. Consider the

decision to purchase a new automobile. Numerous factors go into such a decision, such as the cost

of the car, the importance of fuel economy, safety features, the resale value, and maintenance costs.

Making a rational decision requires that you first obtain all this information. The neoclassical

approach tends to assume that rational economic actors have “complete information” concerning

each choice in front of them. A variation on this assumption is that people will optimize by

collecting information until the perceived costs of acquiring additional information exceed the

perceived benefits. However, there is a logical problem with this assumption, as Nobel Laureate

Herbert Simon points out: one cannot know if that extra information was worth the cost of

gathering it until it has been gathered! Maybe some additional searching will yield valuable

information, or maybe it won’t.

Simon showed that one first needs to have complete knowledge of all choices in order to

identify the optimal point at which one should cease gathering additional information.

Accordingly, Simon maintained, people rarely optimize. Instead they do what he called satisficing;

they choose an outcome that would be satisfactory (rather than optimal) and then seek an option

that reaches that standard. In other words, they identify an option that is “good enough” rather than

continuing to search for the ideal.

satisfice: to choose an outcome that would be satisfactory and then seek an option that at

least reaches that standard

Economic decisions are always made subject to constraints, including limits on income and

other resources and on physical or intellectual capacities. A universal constraint, for example, is

Essentials of Economics in Context – Sample Chapter for Early Release

DRAFT 13

time—you only have 24 hours in a day to allocate among competing activities such as sleeping,

studying, eating, or entertainment. Given such constraints, satisficing seems to be a reasonable

behavior. If an individual finds that the “satisfactory” level was set too low, a search for options

that meet that level will result in a “solution” rather quickly. In this case, the level may then be

adjusted to a higher standard. Conversely, if the level is set too high, a long search will not yield

an acceptable outcome, and the “satisficer” may lower his or her expectations for the outcome.

Another deviation from maximizing behavior as traditionally defined has been called

meliorating—defined as starting from the present level of well-being and finding opportunities to

do better. A simple example is a line fisherwoman who has found a whole school of haddock but

wants to keep only one for her supper. She first catches a fish. She doesn’t stop there but goes on

to catch a second fish, which she compares to the first one—keeping the larger and releasing the

other. Each subsequent catch is compared to the one she has retained as the largest so far. At the

end of the day, the fish that she takes home will be the largest of all those caught.

meliorating: starting from the present level of well-being and continuously attempting to

do better

One result of using melioration as the real-world substitute for optimization is its

implication that history matters: people view each successive choice in relation to their previous

experience. It is commonly observed that people are reluctant to accept a situation that they

perceive as inferior to previous situations. For example, workers are likely to resist pay cuts or

switch to jobs with lower wages.

Satisficing and meliorating may both be included under the term bounded rationality. The

general idea is that, instead of considering all possible options, people limit their attention to some

more-or-less arbitrarily defined subset of the universe of possibilities. With satisficing or

meliorating behavior, people may not choose the “best” choices available to them, but they at least

make decisions that move them toward their goals.

bounded rationality: the hypothesis that people make choices among a somewhat

arbitrary subset of all possible options due to limits on information, time, or cognitive

abilities

Let us now summarize the current thinking about consumer behavior, in five core

principles, based on two recent journal articles and contrast it to the neoclassical model presented

in Section 2.

15

1. People may try to engage in maximizing behavior, but they often aren’t successful due to

insufficient or inaccurate information, poor judgment, limited resources, and other issues.

We might think of economic decisions as being a somewhat “muddled” process rather than

the maximizing process envisioned by the neoclassical model.

2. People make economic decisions using various reference points to help them. We saw

previously how framing and anchoring can influence economic decisions.

3. Most people have a “present bias” when making decisions with long-term impacts.

Running up large credit card debts and under-investing in education are examples of

“present-bias.”

Essentials of Economics in Context – Sample Chapter for Early Release

DRAFT 14

4. While people often engage in self-interested behavior, they also care about the welfare of

others, even people they do not know. People may care about others in order to increase

their own well-being or out of true altruism and concern for the common good. Any model

that assumes only self-interested behavior is inadequate.

5. The fact that people’s preferences are often not fixed or even fully known to them means

that their decisions can be influenced through framing, anchoring, or present bias. We have

discussed how these techniques may be used by advertisers or politicians to influence

people’s behavior. But such approaches may also be used to design policies that might

encourage people to make healthier and wiser choices, as we will discuss in the final section

of this chapter.

The model just described is supported by many scientific studies, and it is also consistent

with experience and common sense. We are all human beings, often far from perfect, normally

with good intentions but subject to many influential factors.

Discussion Questions

1. Can you think of any economic situations where people seem to make irrational decisions?

For the most part, do you think people are rational or irrational?

2. Discuss how one or more conclusions reached by behavioral economists help you to

understand an experience that you have had making an economic decision.

4. CONSUMPTION IN SOCIAL CONTEXT

In modern societies, consumption is as much a social activity as an economic activity.

Consumption is closely tied to personal identity, and it has become a means of communicating

social messages. We are immersed in the culture of consumerism, where people’s sense of identity

and meaning are often defined through their purchase of consumer goods and services. An

increasing range of social interactions are influenced by consumerist values.

consumerism: having one’s sense of identity and meaning significantly defined through

the purchase and use of consumer goods and services

The rise of consumerism is also deeply connected to capitalism, where the profit-driven

nature of market competition imposes strong pressure on firms to increase their production and

sales. As we will see, firms often devote an enormous amount of resources to advertising and other

marketing strategies to encourage consumption.

Consumption behavior has evolved over time, with influences from various cultural,

religious, political, and social forces, as well as from the availability of environmental resources.

Consumerism is often traced back to the Industrial Revolution, when technological advances in

mass production made it possible to increase consumption levels. The rise of consumerism is also

related to other historical developments such as the invention of department stores, the expansion

of consumer credit (with the invention of credit cards), and changes in work ethics as workers

came to see themselves as consumers and became more inclined to work full-time or even overtime

(instead of advocating for a shorter work week) in order to increase their consumption.

Essentials of Economics in Context – Sample Chapter for Early Release

DRAFT 15

Despite these developments, consumerism has not become a global phenomenon even in

the twenty-first century. Many people around the world are still simply too poor to be considered

modern consumers. Over 700 million people, about 10 percent of humanity lives in “extreme”

poverty, defined by the World Bank as living on less than $1.90 per day.

16

Poverty is about more

than just low income. The United Nations defines absolute deprivation as “a condition

characterized by severe deprivation of basic human needs, including food, safe drinking water,

sanitation facilities, health, shelter, education and information.”

17

The poorest of developing

countries, particularly in sub-Saharan Africa and Southern Asia, often lack the resources needed

to lift their populations out of absolute deprivation.

absolute deprivation: severe deprivation of basic human needs

Additionally, in numerous places around the world, cultural and religious values exist that

seek to restrain the consumer society. For example, Buddhism teaches a “middle path” that

emphasizes material simplicity, nonviolence, and inner peace. Even in the United States, some

Americans are motivated to lower their consumption levels with the goal of reducing

environmental impacts and focusing more on social connections. In this section, we discuss some

social aspects that influence consumer behavior.

4.1 SOCIAL COMPARISONS

As social beings, we compare ourselves to other people. In a consumer society, such comparison

is commonly in terms of income and consumption levels. We are often motivated to maintain a

material lifestyle that is comparable to a reference group, which includes people around us who

influence our behavior because we compare ourselves to them. Most people have various reference

groups, traditionally including our neighbors, our coworkers, and other members of our family.

We are also influenced as consumers by aspirational groups, groups to which a consumer wishes

he or she could belong. People often buy, dress, and behave like the group—corporate executives,

rock stars, athletes, or whoever—with whom they would like to identify.

reference group: the group to which an individual compares himself or herself

aspirational group: the group to which an individual aspires to belong

This tendency to compare ourselves with a reference group has evolved over time.

Economist Juliet Schor suggests that in the 1950s and 1960s, people usually compared themselves

to individuals with similar incomes and backgrounds, but in recent decades, people have become

“more likely to compare themselves with, or aspire to the lifestyle of, those far above them in the

economic hierarchy.”

18

One reason for this might be the transformation in media representation,

which has over time become increasingly depicted by upper-class lifestyles. Schor’s research

indicates that the more television one watches, the more he or she is likely to spend, holding other

variables, such as income, constant.

Schor concludes that identifying with unrealistic aspirational groups leads many people to

consume well above their means, acquiring large debts and suffering frustration, as they attempt

to join those groups through their consumption patterns but fail to achieve the income to sustain

them. Because people tend to evaluate themselves relative to reference and aspirational groups,

increasing inequality may result in people feeling as if they are falling behind even when their

incomes are actually increasing. Schor goes on to note that:

Essentials of Economics in Context – Sample Chapter for Early Release

DRAFT 16

The problem is not just that more consumption doesn’t yield more satisfaction, but

that it always has a cost. The extra hours we have to work to earn the money cut

into personal and family time. Whatever we consume has an ecological impact. . . .

We find ourselves skimping on invisibles such as insurance, college funds, and

retirement savings as the visible commodities somehow become indispensable. . . .

We are impoverishing ourselves in pursuit of a consumption goal that is inherently

unattainable

.

19

Modern technology means that nearly everyone has some exposure to the “lifestyles of the

rich and famous” engaging in conspicuous consumption. The result is the creation of widespread

feelings of relative deprivation, that is, the sense that one’s own condition is inadequate because

it is inferior to someone else’s circumstances. Such feelings can diminish individual well-being

and one’s sense of self-respect and self-confidence. Relative deprivation is a condition that exists

in all countries to some extent, but it is more extreme in countries where the gap between rich and

poor is greatest.

relative deprivation: the feeling of insufficiency that comes from comparing oneself with

someone who has more

4.2 ADVERTISING

Advertising is central to the rise of consumerism. As Christopher Lasch writes,

The importance of advertising is not that it invariably succeeds in its immediate

purpose, . . . but simply that it surrounds people with images of the good life in

which happiness depends on consumption. The ubiquity of such images leaves little

space for competing conceptions of the good life.

20

Though advertising is often justified by economists as a source of information about the

goods and services available in the market, a vast amount of advertising sells consumer culture

and influences consumers’ values and their spending behavior. Recent research shows that

advertising is associated with problems such as obesity, attention deficit disorder, heart disease,

and other negative consequences. Furthermore, advertising commonly portrays unrealistic body

images, traditionally for women but more recently for men as well. (See Box 4.2.)

Global advertising expenditures were about $520 billion in 2016, equivalent to the national

economy of Argentina or Sweden. About one-third of global advertising spending takes place in

the United States. According to one estimate, Americans are exposed to around 5,000 commercial

messages per day, up from around 2,000 per day in 1980s.

21

China recently became the world’s

second-largest advertising market.

BOX 4.2 WOMEN AND ADVERTISING

A 2007 report by the American Psychological Association concluded that advertising and

other media images encourage girls to focus on physical appearance and sexuality, with

harmful results for their emotional and physical well-being.

22

The research project reviewed

data from numerous media sources and found that 85 percent of the sexualized images of

children were of girls. The lead author of the report, Dr. Eileen L. Zurbriggen, points out that

Essentials of Economics in Context – Sample Chapter for Early Release

DRAFT 17

the sexualization of girls in media is likely to have negative effects on girls in a variety of

domains, including cognitive functioning, physical and mental health, and healthy sexual

development. She concludes, “As a society, we need to replace all of these sexualized images

with ones showing girls in positive settings—ones that show the uniqueness and competence

of girls.”

Three of the most common mental health problems associated with exposure to

sexualized images and unrealistic body ideals are eating disorders, low self-esteem, and

depression. It is estimated that 8 million Americans suffer from an eating disorder—7 million

of them women.

23

According to a 2012 article, most female models would be considered

anorexic according to their body mass index. Twenty years ago, the average model weighed 8

percent less than the average woman; now it is 23 percent less.

24

Jean Kilbourne, an author and filmmaker, has been lobbying for advertising reforms

since the 1960s. She has produced four documentaries on the negative effects of advertising on

women, most recently in 2010, under the title Killing Us Softly. Kilbourne notes that virtually

all photos of models in advertisements have been touched up, eliminating wrinkles, blemishes,

extra weight, and even skin pores. She believes that we need to change the environment of

advertising through public policy.

25

4.3 PRIVATE VERSUS PUBLIC CONSUMPTION

The growth of consumerism has altered the balance between private and public consumption.

Public infrastructure has been shaped by the drive to sell and consume new products, and the

availability of public and private options, in turn, shapes individual consumer choices.

In the early 1930s, for example, many major U.S. cities—including Los Angeles—had

extensive and nonpolluting electric streetcar systems. However, due to a range of factors, including

unsupportive policies, poor city planning, and the actions of companies such as General Motors in

buying up streetcar systems and then converting many of them to buslines, the presence of

streetcars declined in many U.S. cities.

26

The ongoing viability of streetcar systems elsewhere in

the United States, and across the world, suggests that many of the streetcar systems could have

continued had the playing field been more level. U.S. government support for highway

construction in the 1950s further hastened the decline of rail transportation, made possible the

spread of suburbs far removed from workplaces, and encouraged the purchase of automobiles.

These examples illustrate that many of the choices that you have, as an individual, depend

on decisions made for you by businesses and governments. Living in Los Angeles today would be

significantly different if it had better maintained and supported its streetcar system rather than cars

and buses. As more people carry cell phones and bottled water, pay telephones and drinking

fountains either cease to exist or become less well maintained, leading more people to carry cell

phones and bottled water. The tradeoffs between public infrastructure and private consumption are

significant. As economist Robert Frank notes, “at a time when our spending on luxury goods is

growing four times as fast as overall spending, our highways, bridges, water supply systems, and

other parts of our public infrastructure are deteriorating, placing lives in danger.”

27

4.4 AFFLUENZA AND VOLUNTARY SIMPLICITY

One of the main lessons of economics is that we should always weigh the marginal benefits of

something against its marginal costs. In the case of consumerism, these costs include less time for

Essentials of Economics in Context – Sample Chapter for Early Release

DRAFT 18

leisure, friends, and family; greater environmental impacts; and negative psychological and

physical effects. In short, there can be such a thing as too much consumption—when the marginal

benefits of additional consumption are exceeded by the associated marginal costs.

Two public television specials, as well as a book,

28

refer to the problem of “affluenza”—a

“disease” with symptoms of “overload, debt, anxiety and waste resulting from the dogged pursuit

of more.” Some people see the solution to affluenza as rejecting consumerism as a primary goal in

life. The term voluntary simplicity refers to a conscious decision to live with a limited or reduced

level of consumption in order to increase one’s quality of life.

voluntary simplicity: a conscious decision to live with a limited or reduced level of

consumption in order to increase one’s quality of life

The motivations for voluntary simplicity vary, including environmental concerns, a desire

to have more free time to travel or raise a family, and to focus on non-consumer goals. Voluntary

simplicity does not necessarily mean rejecting progress or living a life of poverty. Some people

ascribing to voluntary simplicity have left high-paying jobs after many years, while others are

young people content to live on less.

Perhaps the unifying theme for those practicing voluntary simplicity is that they seek to

determine what is “enough”—a point beyond which further accumulation of consumer goods is

either not worth the personal, ecological, and social costs or simply not desirable. Unlike

traditional economics, which has assumed that people always want more goods and services,

voluntary simplicity sees these as only intermediate goals toward more meaningful final goals.

(See Box 4.3.)

BOX 4.3 VOLUNTARY SIMPLICITY

Greg Foyster had a good job in advertising in Australia. But in 2012, he and his partner Sophie

Chishkovsky decided to give up their consumer lifestyles and bicycle along the coast of

Australia, interviewing people who have decided to embrace voluntary simplicity and

eventually write a book about their experience.

Voluntary simplicity is a growing movement in Australia, with several popular

websites and a regular column on the topic in the Australian Women’s Weekly. Foyster

explains:

The overall idea is that you should step out of the consumer economy that

we’re all plugged into and start doing things for yourself because that is how

you’ll find happiness. The best way to think of it is as an exchange. In our

society people trade their time for money, and then they spend that money on

consumer items. . . . It’s really about stepping back and deciding what’s

important to you in your life.

Foyster found that his career in advertising conflicted with his personal sense of ethics.

His “eureka” moment came during an advertising awards event when he saw colleagues being

praised for their efforts to sell people products they didn’t need or even want. He realized that

most of the world’s environmental problems stem from overconsumption, not overpopulation.

He says:

Essentials of Economics in Context – Sample Chapter for Early Release

DRAFT 19

When I worked in advertising, I had a decent income, I had a prestigious job,

and I was miserable. I chose to leave the industry because it wasn’t making me

happy; it wasn’t my purpose in life. And now I have a much lower income; I

work as a freelance writer, which isn’t the most prestigious job. But I am so

much more happy because I know what is important to me and I’m doing what

I love and I have everything I need.

29

Discussion Questions

1. What are your reference groups? Describe why you consider these your reference groups.

What are your aspirational groups? Why do you aspire to be a member of these groups?

2. Think about at least one fashion item you own, such as an item of clothing, jewelry, or

accessory, that you think says a lot about who you are. What do you think it says about

you? Do you think others interpret the item in the same way that you do? How much do

you think that you were influenced by advertising or other media in your views about the

item?

5. CONSUMPTION IN AN ENVIRONMENTAL CONTEXT

The production process that creates every consumer product requires natural resources and

generates some waste and pollution. However, we are normally only vaguely aware of the

ecological impact of the processes that supply us with consumer goods. Most of us are unaware

that, for example, it requires about 600 gallons of water to make a quarter-pound hamburger or

that making a computer chip generates 4,500 times its weight in waste.

30

(See Box 4.4.)

BOX 4.4 THE ENVIRONMENTAL STORY OF A T-SHIRT

T-shirts are perhaps the most ubiquitous article of clothing. What are the environmental

impacts of one T-shirt?

31

Consider a cotton/polyester blend T-shirt, weighing about 4 ounces. Polyester is made

from petroleum—a few tablespoons are required to make a T-shirt. During the extraction and

refining of the petroleum, one-fourth of the polyester’s weight is released in air pollution,

including nitrogen oxides, particulates, carbon monoxide, and heavy metals. About ten times

the polyester’s weight is released in carbon dioxide, contributing to global climate change.

Cotton grown with nonorganic methods relies heavily on chemical inputs. Cotton accounts for

10 percent of the world’s use of pesticides. A typical cotton crop requires six applications of

pesticides, commonly organophosphates that can damage the central nervous system. Cotton is

also one of the most intensely irrigated crops in the world, contributing to water shortages for

other uses.

T-shirt fabric is bleached and dyed with chemicals including chlorine, chromium, and

formaldehyde. Cotton resists coloring, so about one-third of the dye may be carried off in the

waste stream. Most T-shirts are manufactured in Asia and then shipped by boat to their

destination, with further transportation by train and truck. Each transportation step involves the

release of additional air pollution and carbon dioxide.

Essentials of Economics in Context – Sample Chapter for Early Release

DRAFT 20

Despite the impacts of T-shirt production and distribution, most of the environmental

impact associated with T-shirts occurs after purchase. Washing and drying a T-shirt just ten

times requires about as much energy as was needed to manufacture the shirt. Laundering will

also generate more solid waste than the production of the shirt, mainly from sewage sludge

and detergent packaging.

How can one reduce the environmental impacts of T-shirts? One obvious step is to

avoid buying too many shirts in the first place. Buy shirts made of organic cotton or recycled

polyester, or consider buying used clothing. Wash clothes only when they need washing, not

necessarily every time you wear something. Make sure that you wash only full loads of

laundry, and wash using cold water whenever possible. Finally, avoid using a clothes dryer—

clothes dry naturally for free by hanging on a clothesline or a drying rack.

5.1 THE LINK BETWEEN CONSUMPTION AND THE ENVIRONMENT

One measure used to quantify the ecological impacts of consumerism is the amount of “trash”

generated by an economy. In 2014, the U.S. economy generated over 250 million tons of municipal

solid waste, which consisted mostly of paper, food waste, and yard waste.

32

But most of the waste

generation in a consumer society occurs during the extraction, processing, or manufacturing

stages—these impacts are normally hidden from consumers. According to a 2012 analysis, the

U.S. economy requires about 8 billion tons of material inputs annually, which is equivalent to more

than 25 tons per person.

33

The vast majority of this material is discarded as mining waste, crop

residue, logging waste, chemical runoff, and other waste prior to the consumption stage.

Perhaps the most comprehensive attempt to quantify the overall ecological impact of

consumption is the ecological footprint measure. This approach estimates how much land area a

human society requires, both to provide all that it takes from nature and to absorb the society’s

waste and pollution. Although the details of ecological footprint calculations are subject to debate,

it does provide a useful way to compare the overall ecological impact of consumption in different

countries.

ecological footprint: a measure of the human impact on the environment, measured as the

land area required to supply a society’s resources and assimilate its waste and pollution

We see in Figure 4.5 below that the ecological footprint per capita varies significantly

across countries. The United States has one of the highest per-capita ecological footprints (the per-

capita footprints of only six countries are higher, the highest being Qatar).

34

The average European

has a footprint about 40 percent lower than the average American, while the average Chinese has

a footprint that is only one-quarter of that of a U.S. citizen.

Perhaps the most significant implication of the ecological footprint research is that the

world is now in a situation of “overshoot”—our global use of resources and generation of waste

exceeds the global capacity to supply resources and assimilate waste, by about 60 percent. As seen

in Figure 4.5, the total amount of productive area available on earth (the average “biocapacity”) is

only 1.63 hectares per person. In other words, for humans to live in an ecologically sustainable

manner, the average person’s ecological impacts could only be about that of the average

Indonesian. However, an increasing number of people in the world seek to consume at a level

equivalent to a typical American. We would require five earths to provide the resources needed

and assimilate the waste to meet such a demand.

Essentials of Economics in Context – Sample Chapter for Early Release

DRAFT 21

Figure 4.5 Ecological Footprint per Capita, Select Countries, 2016

Source: Global Footprint Network, 2019.

5.2 GREEN CONSUMERISM

Green consumerism means making consumption decisions at least partly on the basis of

environmental criteria. Clearly, green consumerism is increasing: more people are recycling, using

reusable shopping bags and water containers, buying hybrid or electric cars, and so on. Yet some

people see green consumerism as an oxymoron—that the culture of consumerism is simply

incompatible with environmental sustainability.

green consumerism: making consumption decisions at least partly on the basis of

environmental criteria

Green consumerism comes in two basic types:

1. “Shallow” green consumerism: consumers seek to purchase “ecofriendly” alternatives but

do not necessarily change their overall level of consumption

2. “Deep” green consumerism: consumers seek to purchase ecofriendly alternatives but also,

more importantly, seek to reduce their overall level of consumption

Someone who adheres to shallow green consumerism might buy a hybrid or electric car

instead of a car with a gasoline engine or a shirt made with organic cotton instead of cotton grown

with the use of chemical pesticides. But those practicing deep green consumerism would, when

feasible, take public transportation instead of buying a car and question whether they really need

Essentials of Economics in Context – Sample Chapter for Early Release

DRAFT 22

another shirt. In other words, in shallow green consumerism, the emphasis is on substitution, while

in deep green consumerism, the emphasis is on a reduction in consumption.

Ecolabeling helps consumers make environmentally conscious decisions. An ecolabel can

provide summary information about environmental impacts. For example, stickers on new cars in

the United States rate the vehicle’s smog emissions on a scale from one to ten. Ecolabels are placed

on products that meet certain certification standards. One example is the U.S. Environmental

Protection Agency’s Energy Star program, which certifies products that are highly energy

efficient.

ecolabeling: product labels that provide information about environmental impacts or

indicate certification

In addition to environmental awareness by consumers, many businesses are seeking to

reduce the environmental impacts of their production processes. Of course, some of the motivation

may be to increase profits or improve public relations, but companies are also becoming more

transparent about their environmental impacts. The Global Reporting Initiative (GRI) is a nonprofit

organization that promotes a standardized approach to environmental impact reporting. In 2017,

82 percent of the world’s 250 largest corporations used the GRI methodology, including Coca-

Cola, Wal-Mart, Apple, and Verizon.

Discussion Questions

1. Think about one product you have purchased recently and list the environmental impacts

of this product, considering the production, consumption, and eventual disposal of it. What

steps do you think could be taken to reduce the environmental impacts associated with this

product?

2. Do you think that green consumerism is an oxymoron? Do you think that your own

consumer behaviors are environmentally sustainable? Why or why not?

6. POLICY INFERENCES FROM OUR MODEL OF CONSUMER

BEHAVIOR

If one assumes that individuals always have perfect information and that they use that information

to make the best choice, then one tends to see little role for government. For example, why would

we require consumer protection law if consumers know the full consequences of buying something

and always choose well? The model of economic behavior presented in this chapter, however,

indicates that economic actors often do not behave rationally or have complete information and

stable preferences. Their behavior is often significantly influenced by various contextual factors.

Adopting a contextual model of behavior justifies the need for a more active role of government

policy in affecting market outcomes.

6.1 PREDICTABLE IRRATIONALITY AND NUDGES

It is important to realize that while economic behavior is often irrational, it is not random.

Deviations from “optimal” behavior are typically in a specific direction. For example, most people

irrationally under-save for retirement rather than over-save. People tend to place too little value on

Essentials of Economics in Context – Sample Chapter for Early Release

DRAFT 23

the future and tend to eat foods that aren’t healthy enough. A leading behavioral economist Dan

Ariely notes that rationality is the exception rather than rule:

We are all far less rational in our decision making than standard economic theory

assumes. Our irrational behaviors are neither random nor senseless—they are

systematic and predictable. We all make the same types of mistakes over and over,

because of the basic wiring of our brains.

35

So if people continually make mistakes in the same direction, how can policies be devised

to help them make “better” decisions? One answer comes from the 2008 book Nudge, by Richard

Thaler and Cass Sunstein.

36

They advocate for policy “nudges” that encourage, but don’t force,

people to make certain decisions—an approach they refer to as libertarian paternalism. While

they recognize that these two terms may seem unappealing and contradictory, they argue that the

libertarian aspect of their strategies lies in the insistence that policies should be designed to

maintain or increase freedom of choice. The paternalism aspect lies in the claim that it is desirable

to design policies and present choices to motivate people to make better choices.

libertarian paternalism: the policy approach advocated in the 2008 book Nudge, where

people remain free to make their own choices but are nudged toward specific choices by

the way policies are designed and choices are presented

Thaler and Sunstein provide numerous examples in their book related to decisions about

health, financial management, education, and the environment. Take the problem of insufficient

saving for retirement. They note that many people intend to increase the amount they save for

retirement but never get around to it. Recognizing this, the book describes the “Save More

Tomorrow” idea, where workers enroll in a program that automatically increases the percent of

their income that is set aside for their retirement each time they get a raise. As increased saving is

timed to correspond with pay raises, workers don’t see their take-home pay go down. Workers

enrolled in the program can opt out of it any time, but most don’t. Evidence shows that the program

is very effective. In one case, implementation of this program increased workers’ retirement

savings from an average of 3.5 percent of their income to 13.6 percent in four years.

Take another example—how to get people to reduce their home energy use. An experiment

in California gave some residents a small electronic ball that would glow red when energy usage

exceeded a given level but glowed green with moderate usage. The results showed that the ball led

to energy use reductions of 40 percent during peak-use periods, while text and e-mail notifications

were ineffective. The key seems to be that the ball makes one’s energy use more visible and

provides an “anchor” for decision-making about energy use.

Governments around the world are increasingly devising policies based on the findings of

behavioral economics, nudging people to make better decisions. For example, in 2007, New

Zealand implemented the KiwiSaver program, which automatically enrolls workers in a national

savings plan for retirement, with a default contribution of 3 percent. Workers have the freedom to

opt out or choose a higher contribution rate. In 2010, the government of the United Kingdom set

up the Behavioral Insights Team, commonly known as the “Nudge Unit,” with the objectives of

“improving outcomes by introducing a more realistic model of human behaviour to policy” and

“enabling people to make ‘better choices for themselves’.”

37

Essentials of Economics in Context – Sample Chapter for Early Release

DRAFT 24

One of the issues studied by the Nudge Unit has been ways to reduce rates of tax evasion.

38

To encourage people to pay their taxes on time, they experimented with various versions of a

reminder letter sent to people who hadn’t yet paid their taxes. Making the letter as simple as

possible did not significantly affect response rates. However, response rates nearly doubled when

people were reminded of social norms such as “9 out of 10 people pay their taxes on time.” This

illustrates that people’s behavior can be influenced when they are nudged to think of themselves

in comparison to others.

As another example, government officials in Bogotá, Colombia, initially responded to a

water shortage by sending residents information about the crisis and asking them to reduce their

usage. Not only was the appeal ineffective, water consumption actually increased as many people

began stockpiling water. The government then changed its strategy, trying to make water

conservation a new social norm. They distributed free stickers with water conservation messages,

to be placed on faucets at offices and schools. Households with exceptional water savings were

presented with small awards and praised in the local media. This latter strategy proved to be much

more effective.

6.2 CONSUMPTION AND PUBLIC POLICY

While government regulations could help address the problem of overconsumption to an extent,

some people may argue that government intrusion into personal consumption decisions is

unwarranted. But current government regulations already influence consumer decisions—for

instance, high taxes on products such as tobacco and alcohol discourage their consumption to some

extent. On the other hand, subsidies are often used to increase the demand for certain products.

Buyers of new electric vehicles in the United States may be eligible to receive a $7,500 federal tax

credit, a subsidy that reduces the environmental externalities of transportation and encourages a

shift away from fossil fuels. Taxes and subsidies can be justified for several reasons, including as

a response to externalities or to achieve some social goal. Thoughtful regulations can encourage

people to make choices that better align with social and personal well-being. We now consider a

range of different policy ideas for responding to concerns about overconsumption.

Flexible Work Hours

One specific policy to reduce the pressure toward consumerism is to allow for more flexibility in

working hours. Current employment norms, particularly in the United States, create a strong

incentive for full-time employment. Employees typically have the option of seeking either a full-

time job, with decent pay and fringe benefits, or a part-time job with lower hourly pay and perhaps

no benefits at all. Thus, even those who would prefer to work less than full-time and make a

somewhat lower salary, say, in order to spend more time with their family, in school, or in other

activities, may feel the imperative to seek full-time employment. With a full-time job, working

longer hours with higher stress, one may be more likely to engage in “retail therapy” as

compensation.

Europe is leading the way in instituting policies that allow flexible working arrangements.

Legislation in Germany and the Netherlands gives workers the right to reduce their work hours,

with a comparable reduction in pay. Sweden and Norway give parents the right to work part-time

when their children are young. Such policies encourage “time affluence” instead of material

affluence. Juliet Schor argues that policies to allow for shorter work hours are also one of the most

effective ways to address environmental problems such as climate change.

39

Those who voluntarily

Essentials of Economics in Context – Sample Chapter for Early Release

DRAFT 25

decide to work shorter hours will be likely to consume less and thus have a smaller ecological

footprint.

Advertising Regulations

Another policy approach to discourage overconsumption is to focus on advertising regulations.

Government regulations in most countries already restrict the content and types of ads that are

allowed, such as the prohibition of cigarette advertising on television in the United States.

Additional regulations could expand truth-in-advertising laws, ensuring that all claims made in ads

are valid. For example, laws in the United States already restrict what foods can be labeled “low

fat” or “organic.” Again, European regulations are leading the way with stricter advertising

regulations, especially for children. For example, Norway has banned all advertising targeted at

children under 12 years old. Regulations in Germany and Belgium prohibit commercials during

children’s TV shows. At least eight countries, including India, Mexico, France, and Japan, have

instituted policies to limit children’s exposure to junk food ads.