Taxation and

Customs Union

Taxation and

Customs Union

Study on the review of the VAT

Special Scheme for travel

agents and options for reform

Final Report

TAXUD/2016/AO-05

Written by KPMG

December 2017

Study on the review of the VAT Special Scheme for travel agents and options for reform

EUROPEAN COMMISSION

Directorate-General for Taxation and Customs Union

Directorate C — Indirect Taxation and Tax Administration

Unit C1 — Value Added Tax

Contact: Arne Kubitza

European Commission

B-1049 Brussels

EUROPEAN COMMISSION

Directorate-General for Taxation and Customs Union

TAXUD/2016/AO-05

Study on the review of the VAT

Special Scheme for travel

agents and options for reform

Final Report

TAXUD/2016/AO-05

EUROPEAN COMMISSION

Directorate-General for Taxation and Customs Union

TAXUD/2016/AO-05

EUROPE DIRECT is a service to help you find answers

to your questions about the European Union

Freephone number (*):

00 800 6 7 8 9 10 11Freephone number (*):

00 800 6 7 8 9 10 11

(*) The information given is free, as are most calls (though some operators, phone boxes or hotels may charge you)

LEGAL NOTICE

The information and views set out in this report are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official

opinion of the Commission. The Commission does not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this study.

Neither the Commission nor any person acting on the Commission’s behalf may be held responsible for the use which

may be made of the information contained therein.

This report is a deliverable of the services contract TAXUD/2016/DE/332 and is not intended to comprise the

provision of advice on any tax matters to other parties. This report is made by KPMG in Ireland, an Irish partnership

and a member firm of the KPMG network of independent firms affiliated with KPMG International Cooperative (“KPMG

International”), a Swiss entity, and is in all respects subject to the agreement and signing of a specific engagement

letter or contract. KPMG International provides no client services. No member firm has any authority to obligate or

bind KPMG International or any other member firm vis-à-vis third parties, nor does KPMG International have any

such authority to obligate or bind any member firm. The KPMG name and logo are registered trademarks of KPMG

International Cooperative (“KPMG International”), a Swiss entity.

More information on the European Union is available on the Internet (http://www.europa.eu).

Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union, 2017

KP-07-17-131-EN-N

ISBN 978-92-79-76931-3

doi:10.2778/078698

© European Union, 2017

Reproduction is authorised provided the source is acknowledged.

5

Table of Contents

1

Executive Summary ........................................................................................................................................... 11

1.1 Background to this report.......................................................................................................................... 11

1.2 Outline of the approach taken ................................................................................................................... 12

1.3 Structure of the report ............................................................................................................................... 12

1.4 Economic analysis .................................................................................................................................... 12

1.5 Evaluating the functioning of the current rules .......................................................................................... 12

1.6 Options for reform ..................................................................................................................................... 13

2 Introduction ........................................................................................................................................................ 15

2.1 Objectives of the study ............................................................................................................................. 15

2.2 Scope ....................................................................................................................................................... 15

2.3 Surveys..................................................................................................................................................... 15

2.4 Quantitative analysis ................................................................................................................................ 16

2.5 Introduction to the travel industry .............................................................................................................. 16

Technological change .............................................................................................................. 17

Sharing economy ..................................................................................................................... 17

Importance of tourism in the EU .............................................................................................. 18

2.6 Definitions ................................................................................................................................................. 22

2.7 Distortion of competition ........................................................................................................................... 23

3 Introduction to the Special Scheme ................................................................................................................. 26

3.1 Relevant VAT Directive Provisions ........................................................................................................... 26

3.2 History of the Special Scheme .................................................................................................................. 26

3.3 Reform of the Special Scheme ................................................................................................................. 26

3.4 Analysis of CJEU case law affecting the Special Scheme ........................................................................ 27

Commission v Germany .......................................................................................................... 27

Van Ginkel ............................................................................................................................... 27

DFDS ....................................................................................................................................... 28

Madgett and Baldwin ............................................................................................................... 28

First Choice ............................................................................................................................. 29

MyTravel .................................................................................................................................. 29

ISt ............................................................................................................................................ 29

Minerva .................................................................................................................................... 30

Commission v Spain et al ........................................................................................................ 30

3.4.9.1 Advocate General’s observations ........................................................................... 30

3.4.9.2 CJEU ...................................................................................................................... 31

Star Coaches ........................................................................................................................... 31

Maria Kozak ............................................................................................................................. 32

Findings in respect of CJEU case law ..................................................................................... 32

4 Description and economic analysis of the travel industry ............................................................................. 35

4.1 Objective................................................................................................................................................... 35

4.2 Section summary ...................................................................................................................................... 35

4.3 Business models ...................................................................................................................................... 35

6

Tour operators ......................................................................................................................... 36

Travel Management Companies (TMC) ................................................................................... 39

Travel agents ........................................................................................................................... 40

Destination Management Companies (DMC) .......................................................................... 42

MICE (Meeting, Incentives, Conference and Events) organisers ............................................ 44

Phase 1 – Qualitative analysis ................................................................................................. 45

4.3.6.1 Decisions of the Commission in areas other than taxation. .................................... 45

Phase 2 – Quantitative analysis .............................................................................................. 47

4.3.7.1 Macroeconomic data............................................................................................... 47

4.3.7.2 Discussion about the data ....................................................................................... 51

4.3.7.3 Other European Countries ...................................................................................... 51

4.3.7.4 North American Economic Data .............................................................................. 52

Findings ................................................................................................................................... 52

5 Evaluate the functioning of the current rules .................................................................................................. 55

5.1 Objective................................................................................................................................................... 55

5.2 Section Summary ..................................................................................................................................... 55

5.3 Defining distortion of competition .............................................................................................................. 55

5.4 Simplification benefits of the Special Scheme .......................................................................................... 56

5.5 Assessment of material issues and potential distortions arising from the current application of the

Special Scheme rules ............................................................................................................................... 56

Non-deductibility of input tax as a result of B2B supplies being taxed under the Special

Scheme ................................................................................................................................... 56

Advantages enjoyed by intermediaries over those falling within the Special Scheme ............. 58

Advantages enjoyed by travel agents incurring costs which may not be subject to VAT ......... 58

The effect of the taxing of the Special Scheme margin at the standard rate ............................ 58

Invoicing .................................................................................................................................. 59

5.5.5.1 B2B Special Scheme supplies – obligation to issue an invoice .............................. 60

5.5.5.2 B2B Special Scheme supplies – requirement to display Special Scheme

margin VAT on the invoice ...................................................................................... 60

5.5.5.3 Invoice reference to the Special Scheme ................................................................ 60

The interaction of the Special Scheme with VAT registration thresholds ................................. 60

Wholesale supplies .................................................................................................................. 61

5.5.7.1 Application by Member States ................................................................................ 61

5.5.7.2 Wholesale supplies of single items ......................................................................... 61

5.5.7.3 Wholesale supplies of packages ............................................................................. 61

5.5.7.4 Domestic accommodation and wholesale supplies ................................................. 62

5.5.7.4.1 Wholesale supplies considered subject to the Special Scheme .................... 62

5.5.7.4.2 Wholesale supplies considered not subject to the Special Scheme .............. 62

5.5.7.5 Wholesale accommodation illustration .................................................................... 63

5.5.7.6 DMC wholesale package illustration ....................................................................... 67

5.5.7.6.1 The DMC is established in the Member State in which the travel

facilities are consumed ................................................................................. 67

5.5.7.6.2 The DMC is established in a different Member State .................................... 69

5.5.7.7 Conclusion on wholesale supplies .......................................................................... 70

Other B2B supplies .................................................................................................................. 70

5.5.8.1 Application by Member States ................................................................................ 70

Meaning of intermediary .......................................................................................................... 71

VAT recovery by businesses receiving Special Scheme supplies ........................................... 71

Scope of the Special Scheme .................................................................................................. 72

5.5.11.1 Single travel services .............................................................................................. 72

5.5.11.2 Differences in what constitutes travel facilities ........................................................ 73

5.5.11.3 Duration .................................................................................................................. 75

7

5.5.11.4 Purchases from non-VAT registered businesses .................................................... 75

5.5.11.5 Electronically supplied services .............................................................................. 75

Mixed packages of in-house and Special Scheme B2B supplies ............................................ 75

5.5.12.1 Invoicing in-house supplies packaged with Special Scheme supplies .................... 75

5.5.12.2 In-house items itemised on an invoice .................................................................... 75

5.5.12.3 Output tax itemised for each element of the mixed package .................................. 76

5.5.12.4 Valuation and Apportionment of a mixed Special Scheme and in-house B2B

Supply ..................................................................................................................... 76

5.5.12.5 Presentation on invoice of apportionment of a mixed Special Scheme and in-

house B2B supply ................................................................................................... 77

Mixed packages of bought-in and intermediary supplies ......................................................... 77

Mixed Packages including bought-in, in-house and intermediary elements ............................. 77

Mixed Packages – conferences and events ............................................................................ 78

Margin calculation .................................................................................................................... 78

5.5.16.1 Practical implications .............................................................................................. 79

5.5.16.2 Retrospective Adjustments ..................................................................................... 80

5.5.16.3 Fixed profit % .......................................................................................................... 80

5.5.16.4 Income subject to the Special Scheme and allowable costs in margin

calculations ............................................................................................................. 80

5.5.16.5 Margin calculated by reference to VAT inclusive costs ........................................... 80

5.6 Competitive advantages enjoyed by travel agents established outside the EU ........................................ 81

Tour operators ......................................................................................................................... 81

DMC ........................................................................................................................................ 81

5.6.2.1 FIT .......................................................................................................................... 81

5.6.2.2 Packages ................................................................................................................ 82

TMC ......................................................................................................................................... 82

Travel agents ........................................................................................................................... 83

5.6.4.1 Electronically supplied services .............................................................................. 83

MICE ........................................................................................................................................ 84

6 Identify, assess and compare options for reform both under the current place of supply rules and

under place of supply rules based on the destination principle ................................................................... 86

6.1 Introduction ............................................................................................................................................... 86

6.2 Section Summary ..................................................................................................................................... 86

6.3 Background .............................................................................................................................................. 86

The VAT Green Paper ............................................................................................................. 86

The 2011 conclusions to the Green Paper consultation .......................................................... 86

The VAT Action Plan ............................................................................................................... 87

6.4 Our approach to the assessment and comparison of reform options ....................................................... 87

6.5 Introduction to the options for reform ........................................................................................................ 87

6.6 The distortions of competition and other material issues we have identified ............................................ 88

6.7 Adoption of the current rules as interpreted by the CJEU by all Member States ...................................... 88

6.8 The proper treatment of a “package” ........................................................................................................ 90

6.9 Mini One Stop Shop (MOSS) .................................................................................................................... 91

6.10 The merits of a margin based Special Scheme ........................................................................................ 91

6.11 What would happen if there was no margin scheme? .............................................................................. 93

6.12 Exemption without credit........................................................................................................................... 95

6.13 The operation of a future Special Scheme................................................................................................ 95

6.14 The nature of the future Special Scheme ................................................................................................. 98

Definition of travel facilities ...................................................................................................... 98

8

Scope of the Special Scheme .................................................................................................. 99

Nature of the calculation of VAT due ....................................................................................... 99

Taxation of the margin at a reduced rate ............................................................................... 100

Application of the Special Scheme to supplies to taxable persons ........................................ 100

6.14.5.1 TMC sector ........................................................................................................... 101

6.14.5.2 MICE ..................................................................................................................... 103

6.14.5.3 DMC...................................................................................................................... 107

6.14.5.3.1 The supply of FIT services ......................................................................... 109

6.14.5.3.2 Creation of a travel package to be sold on a wholesale basis ..................... 110

6.14.5.3.3 Wholesale supply of accommodation by Bed Banks ................................... 112

The Special Scheme opt-out ................................................................................................. 113

6.15 Equality of treatment of EU and third country travel agents .................................................................... 113

Reverse charge ..................................................................................................................... 115

6.16 The use of MOSS for travel services ...................................................................................................... 115

6.17 Future developments in the travel sector ................................................................................................ 115

6.18 Findings .................................................................................................................................................. 116

Abolition of the Special Scheme ............................................................................................ 117

The operation of a future Special Scheme ............................................................................. 118

Annex 1 Questionnaire 1 (current Special Scheme rules as applied by Member States) ............................. 121

Annex 2 Questionnaire 2 (Business Questionnaire) ........................................................................................ 125

2.1 EU businesses ........................................................................................................................................ 125

2.2 Non-EU businesses ................................................................................................................................ 128

Annex 3 Quantitative analysis ............................................................................................................................ 131

3.1 Section 1: Turnover – Europe ................................................................................................................. 131

N79 – Travel Agencies .......................................................................................................... 131

N79.1.2 – Tour operators ....................................................................................................... 131

N79.9.9 - Other ...................................................................................................................... 131

N82.3.0 – Organisation of conventions and trade shows....................................................... 131

3.2 Turnover - North America ....................................................................................................................... 132

561510 Travel Agencies ........................................................................................................ 132

561520 Tour Operators ......................................................................................................... 132

561591 Convention and Visitors Bureaus .............................................................................. 132

561599 All Other Travel Arrangement and Reservation Services ......................................... 132

WTTC – Economic Impact Analysis....................................................................................... 132

3.3 Methodology – Europe ........................................................................................................................... 132

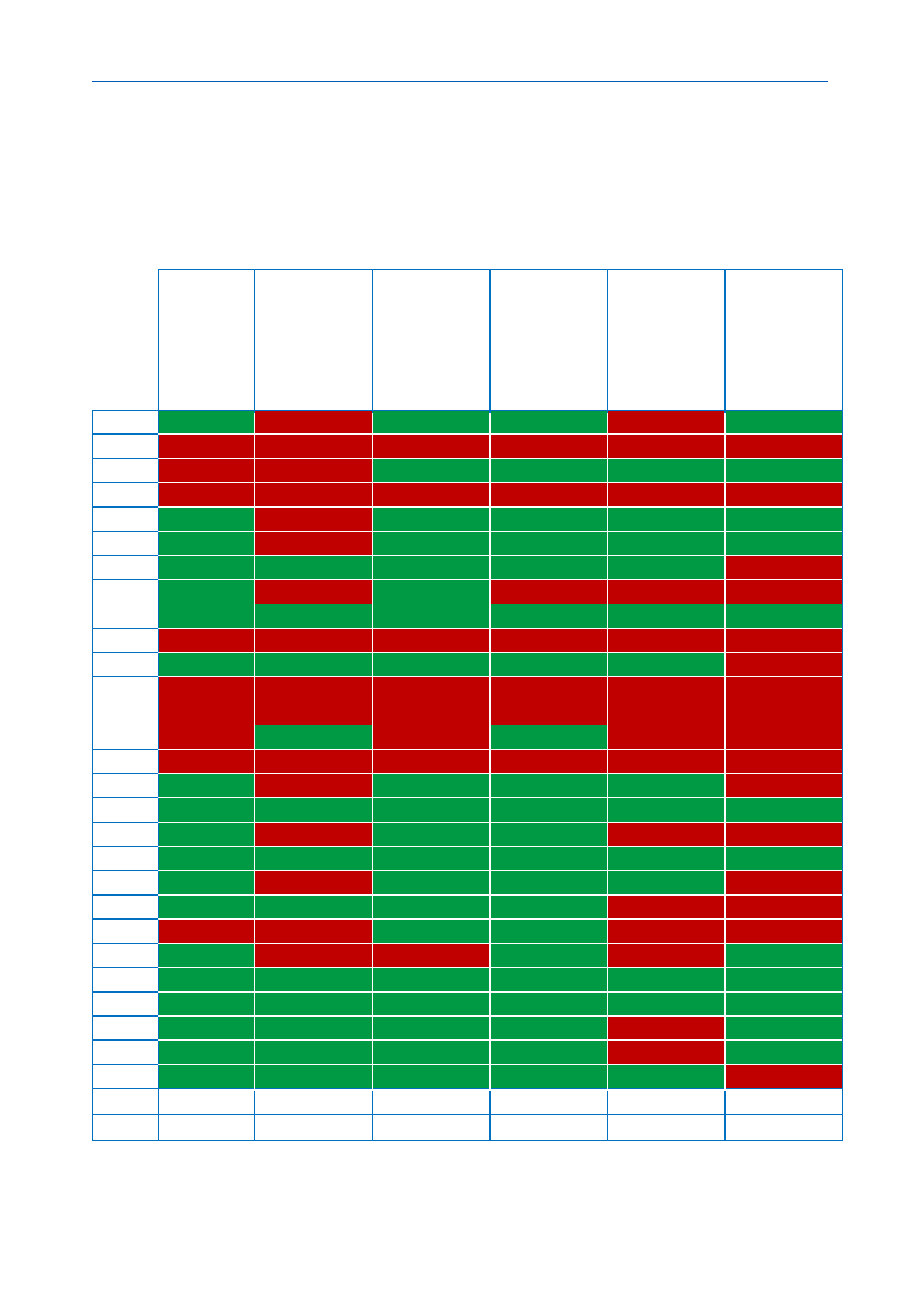

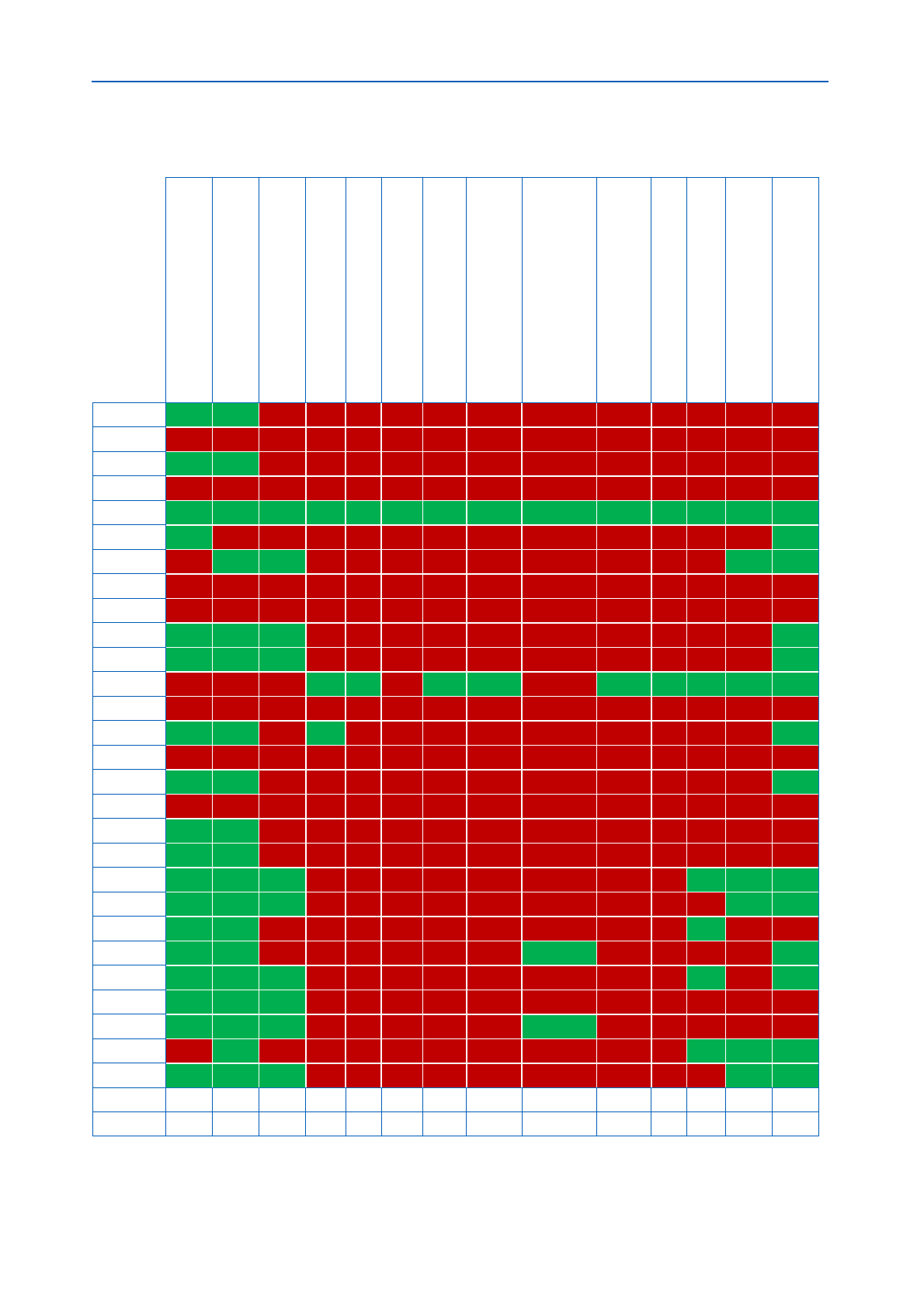

N79 – All – Travel agency, tour operation reservation services and related activities ........... 133

N79.1.1 – Travel agencies ..................................................................................................... 134

N79.1.2 – Tour operators ....................................................................................................... 135

N79.9.9 – Other reservation .................................................................................................. 136

N82.3.0 – Organisation of conventions and tradeshows........................................................ 137

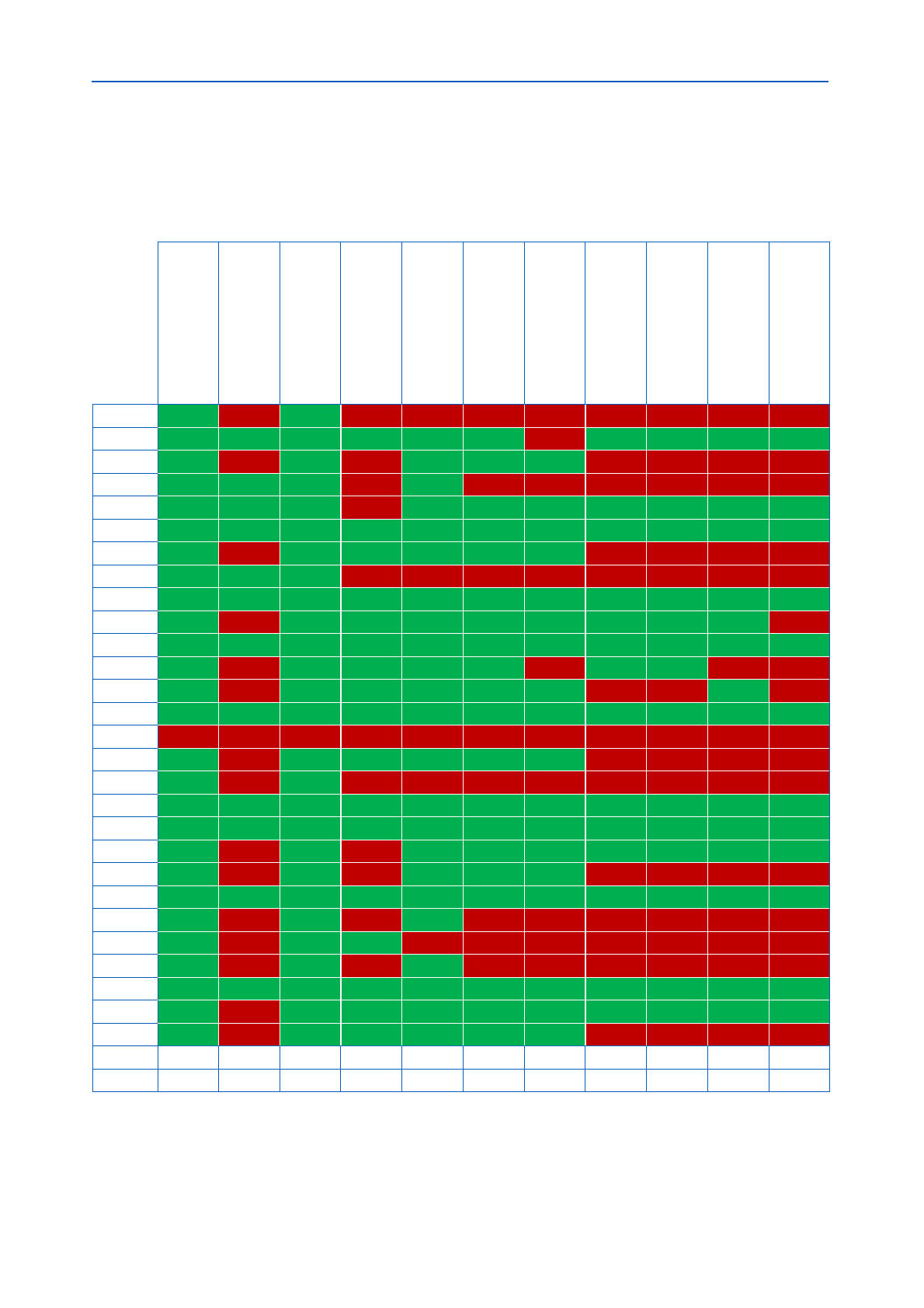

Summary of 2015 data .......................................................................................................... 138

3.4 Business Models Definitions: .................................................................................................................. 141

Tour Operator ........................................................................................................................ 141

Travel Management Companies (TMC) ................................................................................. 141

Travel agents ......................................................................................................................... 141

Destination Management Companies (DMC)/Wholesale Tour Operators ............................. 141

MICE organisers, i.e. Meeting, Incentives, Conferences and Events organisers ................... 141

3.5 NACE Definitions .................................................................................................................................... 141

9

Travel Agent .......................................................................................................................... 141

Tour Operator ........................................................................................................................ 141

Other ...................................................................................................................................... 142

Conventions and Shows ........................................................................................................ 142

Treatment of the data ............................................................................................................ 142

3.6 Methodology – North America ................................................................................................................ 142

Business Models Definitions: ................................................................................................. 143

Tour Operator ........................................................................................................................ 143

Travel Management Companies (TMC) ................................................................................. 143

Travel agents ......................................................................................................................... 143

Destination Management Companies (DMC)/Wholesale Tour Operators ............................. 143

MICE organisers, i.e. Meeting, Incentives, Conferences and Events organisers - mainly

in the corporate segment (B2B). ............................................................................................ 143

3.7 NAICS Definitions ................................................................................................................................... 143

561510 Travel Agencies ........................................................................................................ 143

561520 Tour Operators ......................................................................................................... 143

561591 Convention and Visitors Bureaus .............................................................................. 143

561599 All Other Travel Arrangement and Reservation Services ......................................... 144

3.8 Treatment of the data ............................................................................................................................. 144

3.9 VAT extrapolations ................................................................................................................................. 145

VAT throughput...................................................................................................................... 145

Wholesale illustration ............................................................................................................. 146

Illustrative calculations ........................................................................................................... 147

3.9.3.1 UK to Spain ........................................................................................................... 147

3.9.3.2 Germany to Greece .............................................................................................. 147

3.9.3.3 UK to EU ............................................................................................................... 147

Annex 4 Articles 306 to 310 of the VAT Directive ............................................................................................. 149

4.1 Article 306 ............................................................................................................................................... 149

4.2 Article 307 ............................................................................................................................................... 149

4.3 Article 308 ............................................................................................................................................... 149

4.4 Article 309 ............................................................................................................................................... 149

4.5 Article 310 ............................................................................................................................................... 149

Annex 5 List of common abbreviations used in this study ............................................................................. 151

`

Executive

Summary

11

1 Executive Summary

This report is prepared by KPMG to provide the

European Commission’s Directorate General for

Taxation and Customs Union with an overview of the

functioning of the Special Scheme for travel agents

(“Special Scheme”) contained in Articles 306 to 310 of

the VAT Directive.

1

It also addresses options for

reform in respect of the Special Scheme.

It reviews the history of the Special Scheme and the

influence of relevant judgments by the Court of Justice

of the European Union (“CJEU”) as well as the views

expressed by the Court on the proper functioning of the

scheme.

The Special Scheme has now been in place for over

40 years and must function in a world that has

changed significantly since its inception. These years

have seen enormous growth in international travel,

changes in technology, widespread deregulation

(particularly in the airline industry) and disruptive

business models that have led to ways of conducting

business that would not have been in the mind of the

original drafters of the law. The combination of these

factors, coupled with evolving CJEU case law, have led

us to conclude that modernisation is needed.

Competitive neutrality means that tax-driven price

differences should be eliminated irrespective of how a

transaction occurs. The report identifies two principal

distortions of competition that should be addressed in

order to ensure this happens. The first involves varying

definitions of what constitute “travel facilities” applied in

Member States and secondly, the treatment of B2B

transactions. This latter distortion is of particular

concern to those sectors of the industry whose

activities, by their very nature, are focused on

corporate clients.

The report also identifies material issues where a level

playing field is not assured. Differences in VAT

treatment in practice occur between EU-established

and non-established suppliers. In addition, the

requirement for the margin to be calculated on a

transaction-by-transaction basis is outdated and

unsuited to the complexities of actual business. Non-

deductibility of input tax by a travel agent is also a

significant drawback of the scheme when providing

services to a business client.

As with any tax system, any critical review will always

revert to its role in the raising of revenue. Our

indicative estimate of the amount of VAT actually

collected under the Special Scheme amounts to circa

€1.9bn whilst associated irrecoverable VAT is

indicatively estimated at circa €5.6bn

2

. In aggregate,

these are significant figures but should be read in the

context of an EU VAT system that raises almost €1tn

annually

3

.

We have concluded that the underlying concepts and

the general manner in which the scheme functions are

1

Council Directive 2006/112/EC

2

These figures should be considered to be only indicative estimates of

potential VAT impacts. All the underlying data is necessarily either

approximation or sample-based. Some of the approximations would

still fit for purpose, meeting the objectives of providing

simplicity and raising revenue, particularly where B2C

transactions are concerned. The scheme however was

conceived to deliver these objectives in a significantly

different environment. It now needs to be modernised

to ensure that it continues to deliver for another 40

years.

1.1 Background to this report

The VAT Directive makes special arrangements for

travel agents or tour operators (hereinafter we use the

collective term ‘travel agents’) who deal with customers

in their own name and use the supplies and services of

other businesses (taxable persons) in the provision of

travel facilities.

The resultant Special Scheme was intended to simplify

the application of the VAT rules for these businesses

who otherwise would have faced practical difficulties

and complexities. At the same time it sought to ensure

that tax accrues to the country where the travel

services were actually provided. Although it seemed to

be a very practical and simple taxation scheme for

those concerned, differences in interpretations and in

application in various Member States have arisen.

Over time the practical implementation of these

measures has generally been seen as one of the more

complex areas of VAT demanding specialist

knowledge and experience.

Moreover, a changed business environment has

involved taxpayers and tax administrations dealing with

outdated legislation that, even if applied consistently,

provides a number of functional challenges to

contemporary businesses. The actions of legislators

and regulators have in many instances facilitated the

process of change and ensured a reasonable level of

certainty. In the travel sector, the Commission’s recent

updating of the Package Travel Directive

4

is an

example of this. Modernisation of the VAT rules has

however proven more difficult. A previous attempt at

reform did not come to fruition due to a lack of

consensus in the European Council.

The travel industry is multi-layered, complex and, like

any dynamic business sector, does not remain static. It

is hardly surprising that a tax system unchanged in 40

years is often difficult to apply in practice and has led

to greater controversy and subsequent litigation as the

business models have developed.

Continued growth is forecast for the sector in the EU.

Europe has a larger share of the global market than

any other part of the world and European destinations

dominate any listing of popular choices. Its

contribution to GDP and to employment is widely

acknowledged and a range of public policy priorities

are targeted at ensuring that these benefits endure and

grow.

imply that the estimates are more likely to be over-estimates than

under-estimates but, overall, we cannot confirm this

3

Figure mentioned in the recent Action Plan on VAT COM (2016) 148

final.

4

Directives 2015/2302/EU

12

1.2 Outline of the approach taken

An aim of the study is to evaluate the functioning of the

current VAT rules provided for in the Special Scheme

and identify potential distortions of competition.

Services originating in another country should be taxed

in the same way for VAT purposes as domestic

services. In this respect, it is unnecessary to

demonstrate conclusive distortion of competition by

means of statistics alone. It is sufficient that distortion

of competition should be the likely effect of differences

in taxation.

5

To this end, KPMG queried how the Special Scheme

functioned at national level across the Member States

as well as how businesses perceived its impact. This

was not limited to KPMG clients alone but took an

extensive focus, gathering the views of a wide cross-

section of the industry as well as national and

international trade and professional bodies.

Based on the data received from business as well as

national and EU bodies (notably EUROSTAT and,

where available, national tax statistics), we undertook a

quantitative analysis of the relative significance of

distortions of competition we identified and an

estimation of the quantitative impact of the identified

options for reform on national budget revenues for

Member States.

In line with the Tender Specifications identified by the

Commission Services in respect of the project, this

study reflects the UK as a member of the European

Union.

1.3 Structure of the report

Section 2 sets out the principal parameters of the study

and its objective which, starting from the original aims

of the legislators in 1977, is to consider whether the

way the Special Scheme functions today meets those

aims or whether remedial action is needed. It

describes the approach to information gathering and

sets out an economic profile of the industry and its

significance as well as looking at the hallmarks

identifying how tax can distort the conditions of

competition.

Section 3 describes in detail the history and functioning

of the Special Scheme. It recounts the experiences of

previous attempts at reform and includes a detailed

case-by-case analysis of relevant case law of the

CJEU addressing both infringement proceedings and

referrals. In considering what the Court has said,

particular attention is given to the impact on the

functioning of the Special Scheme as well as the

constraints created by the obligation to avoid

competitive distortion. The Court’s understanding of

the purpose of the Special Scheme as set out in these

judgments has underpinned our evaluation of the

Special Scheme and the consideration of reform

options in sections 6.

5

Article 113 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union

(2012/C-326/01) provides for the harmonisation of VAT legislation to the

extent necessary “to avoid distortion of competition”

6

Study on the impact of EU policies and the measures undertaken in

their framework on tourism, (prepared by Risk & Policy Analysts for DG

1.4 Economic analysis

Section 4 considers the five business models identified

by Commission studies

6

as operating in the tourism

industry, and how VAT impacts on the respective

supply chains. The section provides, on this basis, an

economic analysis of the industry. These models or

business categories must be seen as usefully

indicative rather than reflecting a definitive or exclusive

description, with many travel businesses spanning two

or more of them. They are however a good basis on

which to describe and analyse the manner in which

VAT functions in the travel market. Due to

inconsistencies in how the rules are applied by

different Member States, it is not always easy to make

a “like-for-like” comparison. Nevertheless, this analysis

establishes a firm basis for the more detailed technical

analysis in section 5 and gives context to the

evaluation of alternative reform options at section 6.

The total annual turnover of the EU travel and tourism

sector is calculated at around €187bn per annum

7

. In

broad terms, the Special Scheme taxes only travel,

supplied by EU established businesses, to EU

destinations. We have indicatively estimated the value

of irrecoverable input tax generated by the scheme at

circa €5.6bn annually and output tax (collected on

supplies) at circa €1.9bn. The majority of the tax

collected via the Special Scheme therefore takes the

form of irrecoverable input tax, which generally is

collected in the Member State of destination. The

estimated value of Special Scheme output tax is

smaller in totality, and is collected in the Member

States in which the respective travel businesses are

established.

Although the fundamental feature of blocked input tax

recovery is applied relatively consistently across the

EU and affects all business models in a similar

manner, there are significant differences in

implementation across Member States. This is

explored in section 5. They can impact the different

supply chains associated with the five key business

models in different ways. This section therefore

provides important context for the subsequent section

of the report.

1.5 Evaluating the functioning of

the current rules

Section 5 looks in detail at how the provisions of the

Special Scheme are applied by the Member States.

The two key aims of the Special Scheme are

simplification and efficient revenue allocation between

Member States. Regarding the first of these aims it can

be said that this has been achieved and that travel

agents appreciate the benefit of that simplification,

despite the numerous inconsistences in application as

discussed below.

In the majority of cases it appears that these

discrepancies arise simply from differing local

interpretations of the VAT Directive and/or the case law

Enterprise and Industry, September 2012) and the Study on the

Competitiveness of the EU tourism industry (prepared by Ecorys,

October 2009)

7

Based on data identified for 2015 and as described in Section 4.3.7

13

of the CJEU. It may be considered that this scope for

differing interpretations results from the absence of

precise, prescriptive provisions in the VAT Directive or

implementing regulations. A common feature across

the majority of Member States is that local legislation

and local published tax authority guidance are often

lacking the precision or detail necessary to provide

clarity on the VAT treatment of particular scenarios. As

a result, accepted local practice can be inconsistent

even within a given Member State (and Annex 1, which

summarises differences between Member States,

should be read in this context).

Whilst the inconsistencies create uncertainty and

difficulties for taxpayers operating in multiple Member

States, we have concluded from a quantitative

perspective that many create neither a material issue,

nor a distortion of competition, in aggregate for the EU

as a whole. Even so, on a qualitative basis, given the

difficulties they create it would be advisable to seek

greater harmonisation and to address these points in

the course of reform.

However, a limited number of issues are more

significant and warrant further examination. First, we

have concluded that the different treatment of

wholesale supplies and, secondly, the differing

approaches to the meaning of travel facilities create a

distortion of competition. In addition we have

concluded that the need to calculate the margin VAT

on a transaction by transaction basis and the inequality

between third country suppliers and those established

in the Member States are all material issues for the

industry that merit a resolution. Further, we have

concluded that the inability of a travel agent to deduct

input tax on travel supplies in respect of B2B services,

is a significant drawback of the Special Scheme.

Precise quantification of every potential distortion of

competition was not possible as part of this study,

although the quantitative analysis at section 4 has

informed our conclusions. In the absence of

comprehensive, publicly available economic data, this

study seeks to extrapolate and approximately quantify

the identified distortions of competition by reference to

the likely quantum of “tax collected” in real-world

examples illustrating each of the five business models

identified. Even if the estimates of total Special

Scheme revenue and therefore irrecoverable input tax

can be seen as modest, an issue manifests in the fact

that many travel agencies in the B2B sector operate as

intermediaries and therefore outside the Special

Scheme, thereby reducing VAT revenues under the

Special Scheme. In the DMC sector the issue is more

the inconsistency in the application of the Special

Scheme to wholesale supplies and it is also probable

that VAT revenue would be greater if the rules were

harmonised.

1.6 Options for reform

In section 6 we explain how we have arrived at the

conclusion that reform of the Special Scheme is

desirable.

We have concluded from industry feedback that there

is a lack of desire to abolish the Special Scheme

entirely. Nevertheless there is scope for change in

addressing the issues detailed in section 5.

The question of how travel agents established outside

of the EU who sell to EU consumers might be brought

within the scope of EU VAT needs to be addressed.

This section looks at how this might be done in

practice.

By their nature, many of the options under

consideration here would involve operators being

required to pay VAT in multiple Member States. If the

Commission considers going in that direction, in future,

we believe that an enhanced form of the current Mini

One Stop Shop (“MOSS”) arrangement might be

available to assist travel agents in their compliance

with regard to B2C supplies.

We would like to formally acknowledge and thank the

numerous businesses, travel associations, tax

authorities and experts who contributed to this study.

This study focuses in particular on potential reform

options identified by the Commission Services. We

have considered the possible effects of each option but

have not set out to reach final conclusions on how

reform of VAT as it affects travel agents should

develop in detail. Such conclusions or recommendation

on the details and implementation of any preferred

option go beyond the scope of this study. We have

therefore outlined our view of the likely high-level

effects of the options, informed by our earlier analysis.

It has to be acknowledged that there can be different

perspectives and issues in respect of the reform

options, but we believe our assessment may serve as

a framework for future debate and further analysis

which the Commission will need to undertake.

`

Introduction

15

2 Introduction

2.1 Objectives of the study

This study on the Special Scheme has been

commissioned by the Taxation and Customs Union

Directorate General of the Commission (DG TAXUD).

The overall objective is to consider how the original

objectives of the scheme can best be delivered,

whether these remain valid or are in need of updating

and if there is still a need for the Special Scheme.

This study considers issues by jurisdiction, size and

type of business and then extrapolates to make

findings at an EU level.

2.2 Scope

The following parameters define the scope of the

study:

Geographic scope; and

Business models covered.

With regard to the geographic scope of the study,

countries addressed in the report comprise the 28 EU

Member States as well as certain key non-EU

jurisdictions i.e. Turkey, Switzerland, Norway, the US

and Canada.

The business models covered in the report comprise:

Tour operators - ranging from large international

tour operators to small independent niche

operators (mainly B2C). Tour operators can also

operate “online” for this market

Travel Management Companies (TMC) - which

mainly focus on business travel as intermediaries

and serve primarily corporate customers (B2B)

Travel agents - covering mainly the leisure market

as intermediaries. Travel agents can operate as

“brick & mortar” enterprises or as “online” agents

or both (mainly B2C)

Destination Management Companies (DMC) -

which are mainly operating in the inbound

segment (mainly B2B)

MICE (Meetings, Incentives, Conferences and

Events) organisers – which are mainly operating in

the corporate segment (B2B)

With respect to the availability of underlying economic

data, this study takes into account pre-existing data

sources such as EUROSTAT data, for example, that

help to provide a wider economic backdrop to the

travel industry in the EU as a whole. As these data

sources do not distinguish between the VAT

treatments applicable to respective sales and

purchases, specific surveys (questionnaires) have also

been used to gather additional detailed VAT data from

a representative sample of businesses. The extent of

such data is limited by the willingness of businesses to

respond with what may be perceived as commercially

sensitive financial information, and is further

constrained by the practicalities of conducting a survey

within the limited timeframe. Extrapolation

methodologies have been used to combine survey

responses with macro-economic EUROSTAT data to

provide indicative figures at an EU level which we

believe to be more than reasonably informative for the

purposes of the study.

2.3 Surveys

This section of the report outlines the approach to

usage of surveys (questionnaires) and the responses

thereto.

Surveys have been used in this study for two

purposes:

To collate information on the application of the

Special Scheme local VAT rules from KPMG

specialists across the EU; and

To collate financial information from relevant

businesses, both within and outside the EU, with a

view to quantifying the impact of the Special

Scheme VAT rules.

With regard to surveys issued to KPMG VAT

specialists, a series of questions (the “KPMG

questionnaire”) was designed to obtain responses that

can be meaningfully viewed from a “high-level”, whilst

also capturing specific local detail wherever possible.

This was achieved by a multi-stage questioning format;

seeking first to gather a high-level initial “yes” or “no”

answer which can be quickly compared between EU

Member States, and subsequently to gather

qualifications, caveats and explanations in longer-form

text answers to reveal more detail. Questionnaires

were issued through an online platform in order to

ensure consistency of responses and to provide a clear

audit trail.

With regard to surveys issued to travel businesses, to

maximise the response rate a single questionnaire

(“business questionnaire”) was prepared, minimising

the burden on respondent businesses. The business

questionnaire was issued in a Microsoft Excel

document format to ensure universal accessibility –

whilst drop-down lists and table structures were

employed for consistency of responses. To allow for

consolidation of the survey responses into EU-wide

economic models, this business questionnaire was

formatted in a consistent manner regardless of the

country of response.

We sent this business questionnaire to KPMG clients

and known travel businesses within each of the

business models identified in section 4. We also sent

this business questionnaire to ETOA (European

Tourism Association); ECTAA (European Travel

Agents’ and Tour Operators’ Associations); European

Federation of the Associations of Professional

Congress Organisers (EFAPCO) as well as similar

national bodies in key Member States, for electronic

distribution to member businesses.

While responsiveness and quality of replies could not

be guaranteed as this depends on the goodwill of

respondents, we sought to obtain responses to the

business questionnaire from at least 10 businesses per

business model across each of Germany and the UK,

16

plus a further 10 businesses per business model from

the other 26 Member States, together with Turkey and

Switzerland.

The final responses utilised in the calculations covered

98 businesses in 18 Member States, spanning all five

business models. The total turnover of these

businesses represents approximately 10% of the

estimated EU market (circa €19bn). No responses

were received from non-EU businesses. Meanwhile by

turnover, 94% of the utilised respondent businesses

were based in only five Member States.

The final responses utilised in the calculations covered

98 businesses in 18 Member States, spanning all five

business models. The total turnover of these

businesses represents approximately 10% of the

estimated EU market (circa €19bn). No responses

were received from non-EU businesses. Meanwhile by

turnover, 94% of the utilised respondent businesses

were based in only five Member States.

2.4 Quantitative analysis

The approach to quantitative analysis is as set out

below.

Quantitative analysis is required in this study in respect

of:

The throughput of input and output tax in each of

the 5 key business models (addressed in section 4

of this study);

Quantifying the relative significance of potential

distortions of competition and with regard to B2B

supplies, quantifying the non-deductibility of input

tax in each of the 5 key business models

(addressed in section 5 of this study); and

Estimating the quantitative impacts of each option

on national budget revenues for each Member

State (addressed in section 6 of this study).

This study takes into account pre-existing data sources

such as EUROSTAT data, which does not distinguish

between the VAT treatments applicable to respective

sales and purchases, in addition to data gathered by

the surveys described at section 2.3.

Our figures are based on the information gathered in

the business questionnaire, scaled to and based on

industry turnover figures for the EU as a whole.

Whilst at the outset it was hoped that figures could be

scaled by each Member State and by each business

model, the relatively small sample size in the majority

of Member States meant that specific quantification of

any given issue in a particular Member State is not

possible. However, as an indication of relative value,

the relative sizes by country and by business model of

the figures in the tables at Figs. 4a and 4b in section 4

(turnover by Member State and turnover by business

model) should be borne in mind.

In section 6 our consideration of the quantitative

impacts of identified reform options on national budget

revenues is based on the quantitative outputs from

8

Travel & Tourism: Global Economic Impact & Issues 2017

9

World Economic Forum – Travel & Tourism Competitiveness Report

2017

section 5 (i.e. the percentage impact, relative to

turnover, on our sampled businesses) which we scaled

based on tax figures where these could be obtained

from the respective tax authorities. Where data was not

forthcoming from all tax authorities, an approximation

has been made based on the limited information

available from the business questionnaire (e.g. to

extrapolate from the % impact on our sampled

businesses the estimated impact on total turnover of

the relevant market in each Member State, where such

figures are available).

2.5 Introduction to the travel

industry

The travel sector is one of the most important parts of

the global economy. In 2016, according to the World

Travel and Tourism Council,

8

10% of all employment

worldwide (109 million jobs) was contributed directly by

travel and tourism and the sector contributed US$2.3tn

directly to global GDP.

The sector has grown significantly in recent years and

is forecast to continue to grow at a fast rate driven by

low airfares and various business models that

disintermediate traditional sales channels.

Travel is an important part of the EU economy in

particular. Europe is the largest global travel and

tourism market and attracted 620m of the 1.2bn

international visitors in 2016, almost twice as large as

the second largest market.

9

Several Member States

are amongst the most visited places in the world and

travel and tourism spending in the EU is highly

significant. However, growth in EU tourism is forecast

to be slower than that to be achieved in many other

parts of the world at circa 2% growth in 2016.

10

In this study, we use the definition of travel and tourism

adopted by the World Travel & Tourism Council,

namely “the activity of travellers on trips outside their

usual environment with a duration of less than one

year”. It includes travel for both leisure and business

purposes.

It can be seen that there are broadly three forms of

tourism:

Domestic tourism, i.e. residents of a country

travelling only within that country

Inbound tourism, i.e. non-residents travelling to a

country;

Outbound tourism i.e. residents of one country

travelling within a different country.

The travel sector is complex, comprising intermediaries

of varying descriptions (tour operators, travel agents

etc.) and numerous principal suppliers of services both

directly to travellers and to intermediaries (for example

hotels, airlines, attractions and car rental companies).

Distribution of travel products has become complex,

often involving numerous parties in the distribution

chain. This complexity contributes to difficulties in

compliance with VAT requirements.

10

European Travel Commission Report – Trends and Prospects 2017

17

The sector has changed enormously in recent years,

largely due to technological advances but also

because of deregulation. These developments in

technology have led to significant changes in the ways

in which travel is sold and distributed. For example,

76% of UK consumers purchased a holiday online in

2016,

11

compared to 49% three years earlier.

12

This is

unlikely to be an isolated development and the same

trend can be expected in other EU countries. These

technology changes are a significant contributory factor

to a perception that the VAT rules have become

outdated and require modernisation to reflect how

business is now conducted.

Technological change

Technological change has been highly significant for

many in the travel sector with new sales channels that

did not exist prior to 1995. For example, it has meant

disruption for many travel agents who have had to

adapt to distribution revolutionised by technology. The

growth of online travel agents and distribution direct by

principal suppliers has been marked and has meant

that many traditional travel agents have had to adapt or

disappear. It has also caused a blurring of the

distinction between traditional travel agents and tour

operators, often creating uncertainty over the status of

the supplier for VAT purposes.

These technological changes have facilitated a growth

of Fully Independent Travellers (“FIT”) who make their

own bookings, e.g. holidays and other forms of travel

organised by the FIT via separate bookings of services

from a range of suppliers. Whilst it may be argued that

such a process has been to the benefit of consumers

who enjoy greater choice, such DIY bookings fell

outside the ambit of the Package Travel Directive

13

leaving consumers unprotected in the event of the

failure of any of the suppliers with which they contract.

The response of legislators has been to update the

package travel legislation to broaden the

circumstances in which consumer protection is

provided. This has culminated in the agreement of a

new Package Travel Directive

14

that takes effect

throughout the EU on 1 July 2018.

The development of XML feeds has facilitated the

growth of specialist niche distributors of product, for

example “Bed Banks” and other aggregators. Tour

operators and travel agents now do not need to source

product direct from principal suppliers but rather often

purchase from an online intermediary such as a Bed

Bank. It is not uncommon for a single hotel room to

pass through several intermediaries before being sold

to the final consumer.

These distribution chains have become genuinely

international. Given that each sale of a hotel room is, in

principle, subject to VAT in the Member State in which

the hotel itself is located,

15

such distribution chains

pose a real challenge for the VAT system which can

11

ABTA’s Holiday Habits Report 2016

12

ABTA Consumer Trends Survey 2013

13

Council Directive on package travel, package holidays and package

tours, 90/314/EEC

http://ec.europa.eu/consumers/consumer_rights/travel/package/index_

en.htm

14

Directive 2015/2302/EU of the European Parliament and of the

Council on package travel and linked travel arrangements

15

Article 47 of the VAT Directive

only work in the way intended if each supplier is

registered in each Member State so as to recover input

tax at the previous stage in the distribution chain and

charge output tax on his own supply. There are also a

number of issues that arise from a VAT and cash

management perspective, especially around the

application of tax points and how payment flows

typically work within the industry.

Sharing economy

We have also seen the rise of the “sharing economy”.

Technology is driving new business behaviours,

leading to new entrants in the market that have

disrupted traditional travel.

16

Whilst this trend took off

with leisure travel, it is expected these supply chain

models will increasingly be relevant to business travel

arrangements,

17

and this is already noticeable in North

American corporate travel policies. This trend gives

rise to a number of issues. For traditional travel

operators there is a concern that business is lost to the

sharing economy and that the greater availability of

unregulated accommodation and other services exerts

downward pressure on price, with 32% of travel

businesses saying the sharing economy has had a

negative effect on their business.

18

For governments,

there is a concern that many services provided are not

regulated to the same extent of those provided by the

established operators in the travel sector and that tax

revenue is not collected as easily as from the

established businesses. However, another view is that

the advent of the sharing economy has not so much

detracted from the traditional travel sector as

contributed to a significant growth overall in the

frequency of travel and as a consequence, 47% of

travel businesses say that the sharing economy has a

positive effect on their businesses.

19

The digital economy has also created greater

opportunities for smaller travel and tourism businesses

that have benefitted from improved marketing and

publicity from their own online presence and from

social media and online review sites.

In this study, we are concerned with the application of

the VAT rules to the travel intermediaries

20

and not to

the primary suppliers (the hotels, airlines etc). The

VAT rules in the context of “primary” suppliers are

generally unambiguous and do not therefore require

discussion here. It is important to note that as a result

of this, the vast majority of taxation revenues that are

generated through the travel economy are therefore at

the primary supplier level that are locally collected and

remitted. The detailed analysis that follows looks at

five categories of travel intermediary: tour operators,

travel agents, TMCs, DMCs and MICE organisers.

The nature of the distribution of travel and the

application of VAT in various circumstances are

considered in section 4.

16

PhoCusWright White Paper: Managed Travel 2020

17

ACTE Global research white paper - The Sharing Economy and

Managed Travel

18

World Travel Market Industry Report 2016

19

World Travel Market Industry Report 2016

20

In this context, “intermediary” is used in the general sense, not the

specific definition of the VAT Directive

18

Importance of tourism in the EU

The importance of tourism in the EU is demonstrated

by the fact

21

that six of the ten most visited countries

(by international travellers) in the world in 2016 were

EU Member States:

Fig 2a

1

st

France

3

rd

Spain

5

th

Italy

6

th

Germany

7

th

UK

10

th

Greece

In a similar vein, when it comes to international tourism

earnings,

22

five of the top ten countries in 2015 were

Member States: Spain (3

rd

), France (4

th

), the UK (5

th

),

Italy (7

th

) and Germany (8

th

).

When it comes to individual cities, the EU is less well

represented. Even so, in 2016 London was the second

most visited city in the world and Paris the third.

23

The

relative under-representation of EU cities in the

respective top 10s suggests that travel to the EU is

less focused on large cities and is shared more equally

amongst places of interest.

It is not surprising therefore that travel and tourism are

mainstays of the EU economy. According to the World

Travel & Tourism Council,

24

the direct contributions

(i.e. those generated by those sectors which deal

directly with tourists) of travel and tourism to EU GDP

was €547.9bn (3.7% of the total) and to employment

was 11,409,000 jobs (5% of the total employment).

The total contribution (i.e. including capital investment

by all industries involved with travel and tourism,

21

According to The World Tourism Organisation

22

Also according to The World Tourism Organisation. In this context,

“intermediary” is used in the general sense, not the specific definition

of the EU VAT Directive

government spending in support of tourism activity and

the contribution to GDP and employment of those

employed directly or indirectly by travel and tourism) to

GDP was €1,508.4bn (10.2% of EU GDP) and

26,585,000 jobs (11.6% of the total).

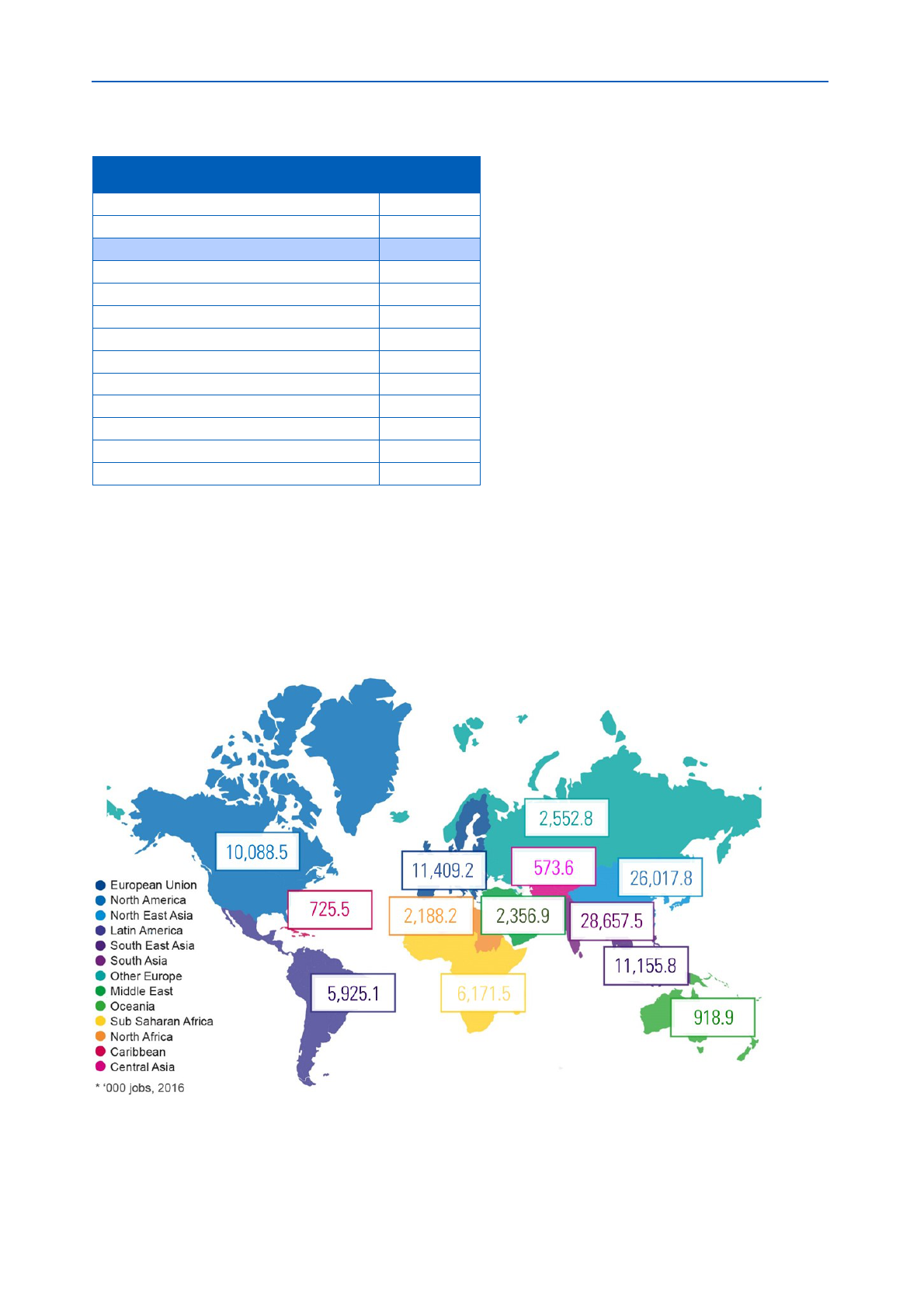

Fig 2b

EU 2016

2016

% of total

2017

% growth

Direct

contribution to

GDP

€547.9bn

3.7

2.9

Total

contribution to

GDP

€1,508.4bn

10.2

2.6

Direct

contribution to

employment

(‘000 jobs)

11,409

5.0

2.8

Total

contribution to

employment

€26,585bn

11.6

2.2

23

According to the MasterCard Global Destination Cities Index (which

based its data on air traffic)

24

Travel & Tourism: Economic Impact 2017 European Union LCU

19

Fig. 2c

Travel & Tourism’s direct contribution to GDP

2016 % share

Caribbean

4.7

South

East Asia

4.7

North

Africa

4.4

European

Union

3.7

Oceania

3.5

Middle East

3.3

Latin America

3.2

South

Asia

3.2

North

America

2.9

Sub

Saharan Africa

2.6

Other

Europe

2.6

North

East Asia

2.5

Central

Asia

1.6

20

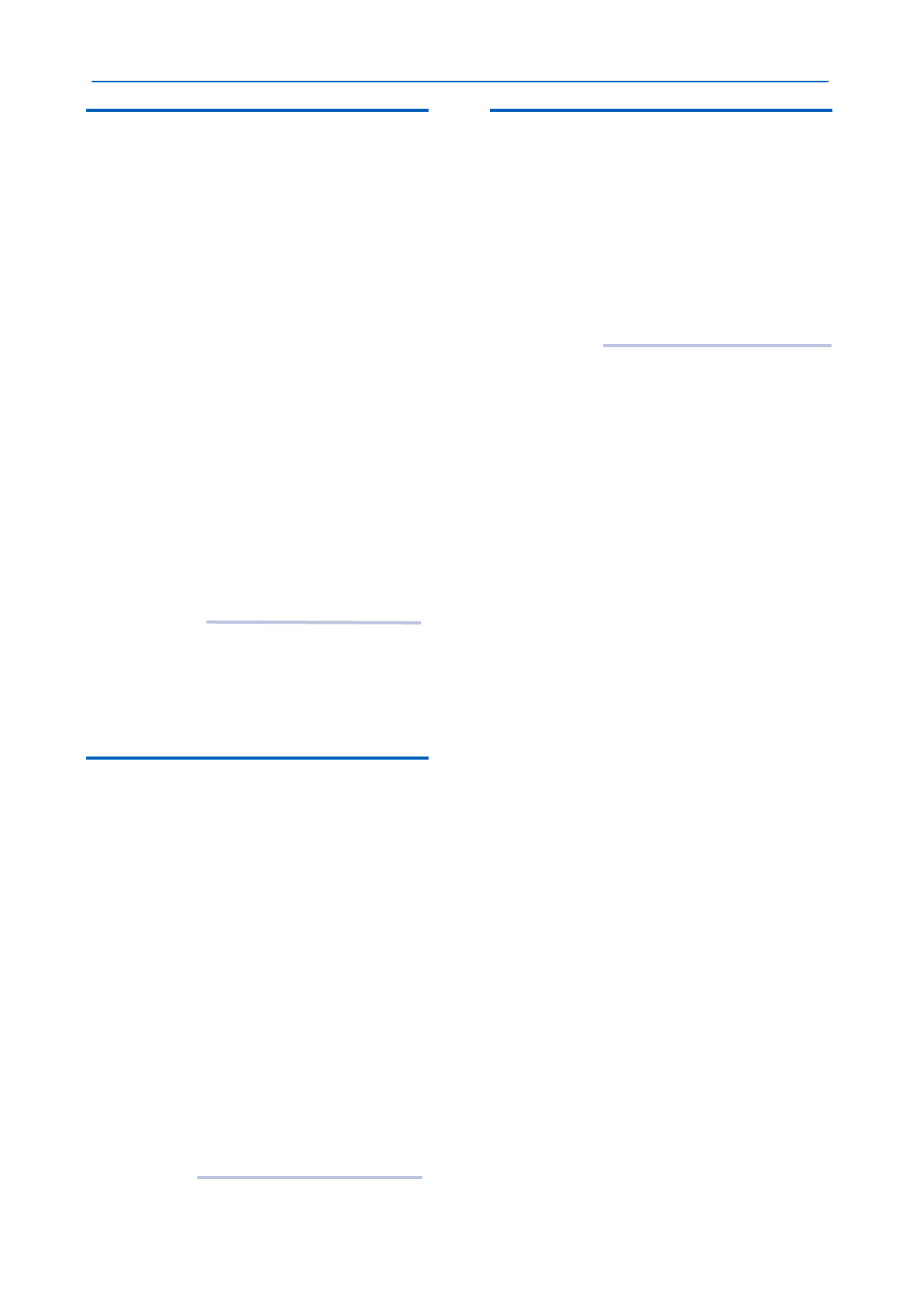

Fig. 2d

Travel & Tourism’s direct contribution to

employment

2016 ‘000 jobs

South

Asia 28,657.5

North East Asia

26,017.8

European

Union 11,409.2

South

East Asia 11,155.8

North

America 10,088.5

Sub

Saharan Africa 6,171.1

Latin

America 5,925.1

Other

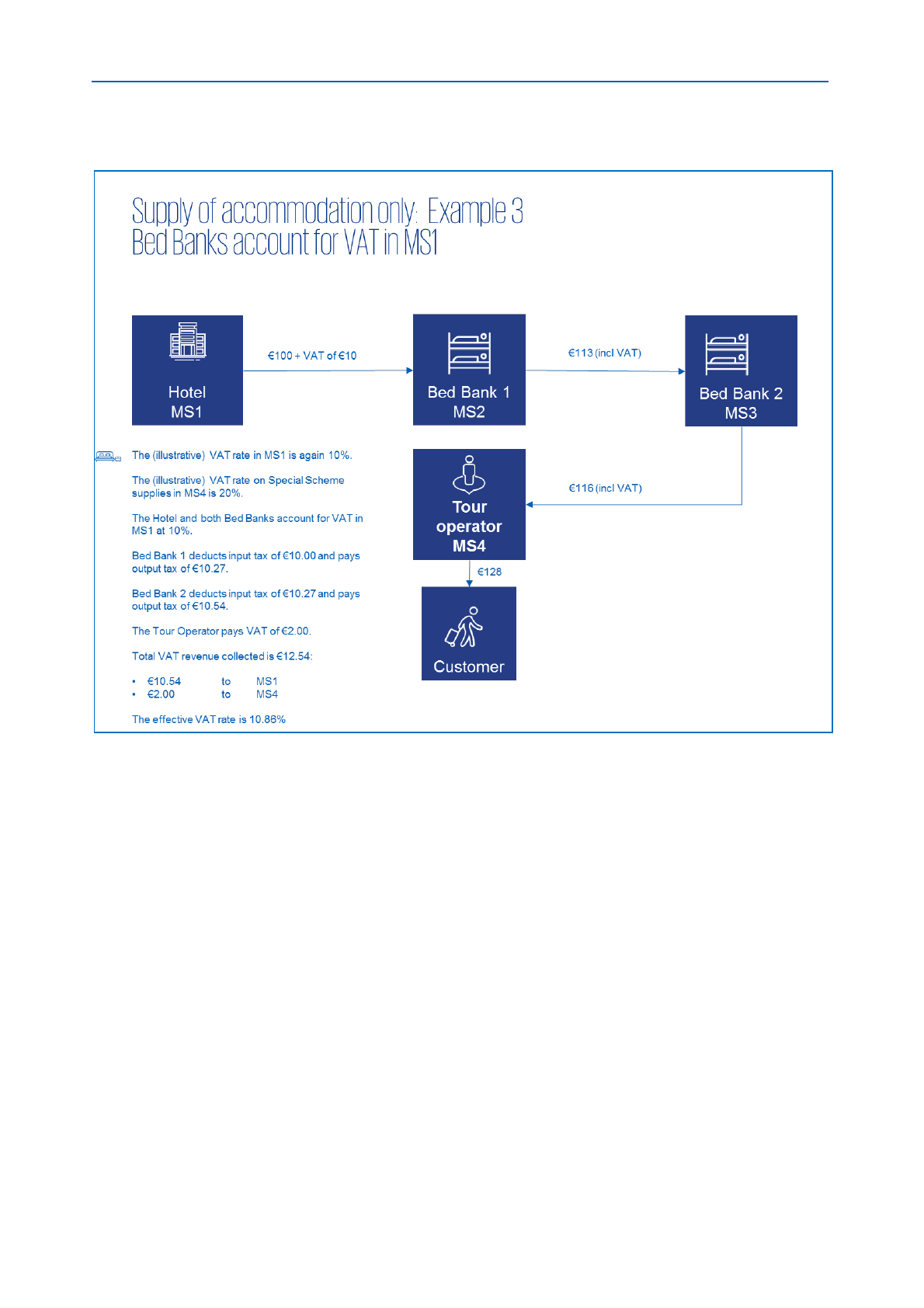

Europe 2,552.8

Middle East

2,356.9

North

Africa 2,188.2

Oceania

9,18.9

Caribbean

725.5

Central

Asia 573.6

21

Fig. 2e

Travel & Tourism’s contribution to employment

2016 % share

European

Union 5.0

South

Asia 5.0

Oceania

4.9

North

America 4.6

Caribbean

4.2

North

Africa 4.0

South East Asia

3.6

Middle

East 3.1

North

East Asia 2.9

Latin

America 2.9

Sub

Saharan Africa 2.4

Central

Asia 1.9

Other

Europe 1.8

22

Travel and tourism’s direct contribution to GDP was

higher (in absolute terms) in the EU than in any other

of the 13 regions of the world used by the World Travel

& Tourism Council.

25

In terms of employment, the

direct contribution made in the EU was the third

highest of the same 13 regions. In relative terms, travel

and tourism’s 3.7% contribution to EU GDP was the

fourth highest of the 13 regions (exceeded only by the

Caribbean, South East Asia and North Africa) and the

contribution to employment was equal first (with South

Asia).

Spending within the EU in 2016 by international

tourists was €377.2bn, comfortably the highest figure

achieved in the 13 regions.

Travel and tourism’s direct contribution to EU GDP is

forecast to grow in 2017 by 2.9%. On the face of it,

this appears impressive but places EU travel and

tourism at only 8

th

place out of the 13 regions when

growth is measured. Over the 10 years to 2027, the

contribution to EU GDP is expected to grow by an

average of 2.3% per annum, the lowest projected rate

of growth of the 13 regions. Over the same period, the

direct contribution to employment is expected to

increase by 1.5% in the EU, the equal lowest rate of

growth of the 13 regions (with Oceania).

Spending in the EU by international tourists in the

period to 2027 is forecast to grow by 3.4% per annum,

a healthy rate of growth on the face of it but only the

12

th

best of the 13 regions (exceeding only North East

Asia).

We can conclude therefore that travel and tourism is

currently a significant part of the economy across the

EU. It is also clear that travel and tourism in the EU are

expected to grow during the next 10 years. However,

the sector’s rate of economic growth in the EU may be

lower than in most other parts of the world. In our

opinion, this would indicate the mature nature of the

EU travel and tourism sector when compared to

relatively newer destinations elsewhere. Given this,

together with the recent and ongoing changes and

disruptions within the sector’s supply chains, it is

prudent to ensure that steps are taken to promote

economic efficiency in the EU’s travel and tourism

sector. The VAT system can be a key consideration in

this.

2.6 Definitions

The following definitions are originally derived from a

2009 Commission Study on the Competitiveness of the

EU tourism industry.

25

The 13 regions are: the EU, other Europe, the Caribbean, South

East Asia, North Africa, Oceania, Middle East, Latin America, South

Asia, North America, Sub Saharan Africa, North East Asia and Central

Asia

2. Travel

Management

Companies

(TMC)

These businesses serve primarily

corporate customers (B2B). TMCs

are able to compare different

itineraries and costs in real-time,

allowing users to access fares for

air tickets, hotel rooms and rental

cars simultaneously and to

prepare bespoke travel plans for

clients.

1. Tour

operators

These businesses range from

large international tour operators

to small independent niche

operators (mainly B2C). Tour

operators organise and provide

package holidays, contracting with

hoteliers, airlines, ground transport