Ethiopia Country Handbook

This handbook provides basic reference information on Ethiopia, including its

geography, history, government, military forces, and communications and trans-

portation networks. This information is intended to familiarize military per sonnel

with local customs and area knowledge to assist them during their assignment

to Ethiopia.

The Marine Corps Intel ligence Activity is the community coordinator for the

Country Hand book Program. This product reflects the coordinated U.S. Defense

Intelligence Community position on Ethiopia.

Dissemination and use of this publication is restricted to official military and

government personnel from the United States of America, United Kingdom,

Canada, Australia, and other countries as required and designated for support

of coalition operations.

The photos and text reproduced herein have been extracted solely for research,

comment, and information reporting, and are intended for fair use by designated

personnel in their official duties, including local reproduction for training. Further

dissemination of copyrighted material contained in this docu ment, to include

excerpts and graphics, is strictly prohibited under Title 17, U.S. Code.

CONTENTS

KEY FACTS .................................................................... 1

U.S. MISSION ................................................................. 2

U.S. Embassy .............................................................. 2

GEOGRAPHY AND CLIMATE ..................................... 4

Geography ................................................................... 4

Land Statistics ........................................................ 5

Borders ................................................................... 6

Border Disputes ..................................................... 6

Bodies of Water ...................................................... 9

Topography ............................................................ 12

Climate ........................................................................ 17

Precipitation ........................................................... 21

Phenomena ............................................................. 21

INFRASTRUCTURE ...................................................... 23

Transportation ............................................................. 23

General Description ............................................... 23

Roads ..................................................................... 23

Rail ......................................................................... 26

Air .......................................................................... 27

Maritime ................................................................ 29

Utilities ........................................................................ 30

Electricity .............................................................. 30

Water ...................................................................... 31

Sanitation ............................................................... 32

Communication ........................................................... 32

Radio ...................................................................... 33

Television ............................................................... 34

iviv

Contents (Continued)

Telecommunication ................................................ 35

Internet ................................................................... 36

Newspapers and Magazines ................................... 37

Postal Service ......................................................... 38

Satellites ................................................................. 38

CULTURE ....................................................................... 39

Statistics ...................................................................... 39

Population Patterns ..................................................... 39

Population of the Major Cities in Ethiopia ............ 42

Population Density ...................................................... 42

Society ........................................................................ 43

People .................................................................... 44

Social Hierarchy .................................................... 48

Family .................................................................... 48

Roles of Men and Women ...................................... 50

Education and Literacy Rates ..................................... 52

Religion ....................................................................... 56

Recreation ................................................................... 59

Customs and Courtesies .............................................. 60

Cultural Considerations .............................................. 63

MEDICAL ASSESSMENT ............................................. 64

Disease Risks to Deployed U.S. Personnel ................. 64

Medical Capabilities ................................................... 67

Medical Facilities ................................................... 68

HISTORY ......................................................................... 70

Chronology of Key Events .......................................... 70

Government ................................................................. 76

National Level ........................................................ 77

Local Level ............................................................ 78

Key Government Officials ..................................... 78

v

v

Contents (Continued)

Politics ........................................................................ 80

Political Parties ...................................................... 80

Foreign Relations ................................................... 81

International Organizations ................................... 84

Non-governmental Organizations .......................... 84

Corruption .............................................................. 85

ECONOMY ..................................................................... 85

Economic Statistics .................................................... 85

General Description ................................................... 86

Economic Aid ............................................................. 87

Banking Services ....................................................... 88

Natural Resources ....................................................... 89

Industry ....................................................................... 89

Mining ................................................................... 90

Manufacturing ....................................................... 90

Leather and Textiles ............................................... 91

Agriculture .................................................................. 92

Foreign Investment ...................................................... 93

Economic Outlook ...................................................... 93

THREAT .......................................................................... 94

Crime .......................................................................... 94

Travel Security ............................................................ 94

Illegal Drugs ................................................................ 95

Foreign Intelligence Services ...................................... 96

Threat to U.S. Personnel ............................................. 97

ARMED FORCES ........................................................... 97

Army ........................................................................... 97

Mission .................................................................. 97

Organization ........................................................... 98

Facilities ................................................................. 98

vivi

Contents (Continued)

Key Defense Personnel .......................................... 98

Personnel ................................................................ 99

Training .................................................................. 100

Capabilities ............................................................ 100

Disposition ............................................................. 100

Uniforms ................................................................ 102

Equipment .............................................................. 102

Air Force ..................................................................... 104

Mission .................................................................. 104

Personnel ................................................................ 104

Training .................................................................. 105

Capabilities ............................................................ 106

Equipment .............................................................. 106

Domestic Security Forces ........................................... 106

National Police ....................................................... 107

Weapons of Mass Destruction .................................... 108

APPENDICES

Equipment Recognition ................................................... A-1

Holidays ........................................................................... B-1

Language .......................................................................... C-1

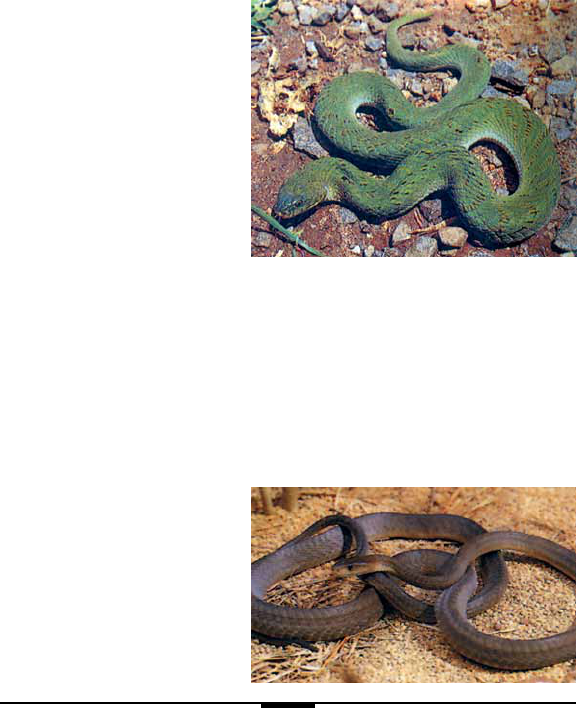

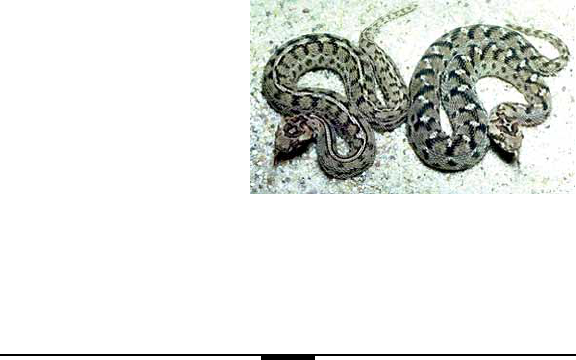

Dangerous Plants and Animals ........................................ D-1

Mines ................................................................................ E-1

Border Delimitation ......................................................... F-1

vii

vii

Contents (Continued)

ILLUSTRATIONS

Ethiopia ............................................................................ ix

National Flag .................................................................... 1

U.S. Embassy in Addis Ababa ......................................... 3

Northeast Africa ............................................................... 5

Disputed Land and Borders ............................................. 7

Ilemi Triangle ................................................................... 10

Topography ...................................................................... 13

Vegetation ........................................................................ 14

Women Shopping at Market ............................................ 17

Addis Ababa and Gonder Weather ................................... 19

Harer and Jima Weather ................................................... 20

Transportation Network ................................................... 24

Donkey Roaming the Streets ............................................ 25

Displaced Popluation ....................................................... 40

Population Density ........................................................... 41

Funeral Procession ........................................................... 44

Primary Somali Refugee Camps ...................................... 47

Ethiopian Woman and Child ............................................ 49

Ethiopian Children ........................................................... 50

Oromo Men Working in Southern Ethiopia ..................... 51

Ethiopian College Students .............................................. 53

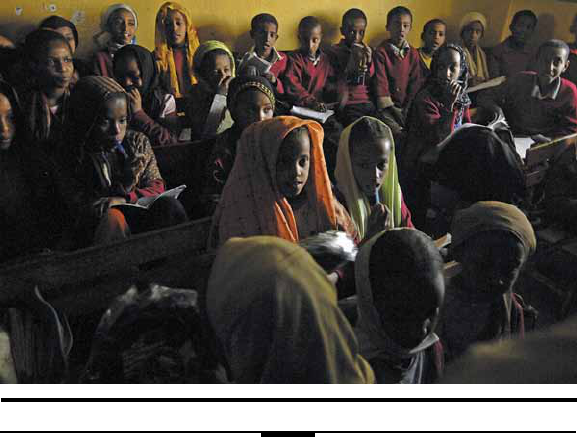

Ethiopian School Children ............................................... 54

Mosque ............................................................................. 56

Ethiopian Orthodox Women ............................................ 57

Muslim Woman ................................................................ 58

Traditional Clothing ......................................................... 62

Stele to King Ezana, First Axum Monarch to

Embrace Christianity ..................................................... 72

viiiviii

Contents (Continued)

Haile Selassie Monument ................................................ 73

Prime Minister Meles Zenawi .......................................... 76

Administrative Regions .................................................... 79

Workers Processing Coffee Beans ................................... 87

Khat .................................................................................. 93

Army Ranks ..................................................................... 99

Army Uniform ................................................................. 100

Ethiopian Troops .............................................................. 101

Air Force Ranks ............................................................... 105

Ethiopian Militias ............................................................. 107

ix

J

u

b

b

a

D

a

w

a

B

a

r

o

T

e

k

e

z

e

B

l

u

e

N

i

l

e

N

i

l

e

W

h

i

t

e

N

i

l

e

Indian

Ocean

Gulf of

Aden

Red

Sea

Lake

Turkana

Kibre

Mengist

Adwa

Nazret

Jijiga

Bonga

Dolo Bay

Dire Dawa

Gonder

Mekele

Nekemte

Dese

Debre

Markos

Gore

Yirga 'Alem

Asela

Harer

Goba

Arba Minch

Jima

KHARTOUM

DJIBOUTI

ADDIS

ABABA

MOGADISHU

ASMARA

SAUDI

ARABIA

YEMEN

SUDAN

UGANDA

KENYA

SOMALIA

DJIBOUTI

ERITREA

44°

36°

4°

12°

Boundary not defined and in dispute

Ethiopia

National Capital

Province Capital

City

Primary Road

Railroad

Province Border

International Border

Disputed Border

0

50

150

0

150 mi

50

100

100

200 km

Ethiopia

1

KEY FACTS

Official Country Name. Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia.

Short Form. Ethiopia.

Local Long Form.

Ityop’iya Federalawi Demokrasiyawi Ripeblik.

Local Short Form. Ityop’iya.

Head of State. President Girma Woldegiorgis (since 8 October 2001).

Capital. Addis Ababa.

National Flag. Equal horizontal bands of green, yellow, and red;

a light blue disk in its center contains a yellow star with yellow

rays emanating outward.

Time Zone. UTC (formerly GMT) + 3 hours.

Telephone Country Code. 251.

Population. 85,237,338 (July 2009 est.)

Languages. Amarigna 32.7%, Oromigna 31.6%, Tigrigna 6.1%,

Somaligna 6%, Guaragigna 3.5%, Sidamigna 3.5%, Hadiyigna

1.7%, other 14.8%, English (major foreign language taught in

schools) (1994 census).

Currency. Birr (ETB).

National Flag

2

Credit/Debit Card Use. Credit cards have limited usage outside

Addis Ababa, and even in the capital, only major establishments

accept them. Most accept only VISA. ATMs are limited to major

bank branches and large hotels.

Calendar. Ethiopian calendar (also known as Ge’ez calendar).

Ethiopia uses the Julian solar calendar, which has its roots in an-

cient Egypt and consists of 12 months of 30 days each and a 13

th

month of 5 or 6 days every 4 years. The Ethiopian calendar runs 7

to 8 years behind the Gregorian (Western) calendar.

U.S. MISSION

U.S. Embassy

The U.S. Embassy is on Entoto Avenue in Addis Ababa.

Location Addis Ababa, Ethiopia

Mailing Address Entoto Avenue, P.O. Box 1014, Addis Ababa

Telephone Number 251-011-517-40-00

Fax Number 251-011-517-40-01, 251-011-124-2401

E-mail Address pasaddis@state.gov

Internet Address http://ethiopia.usembassy.gov/service.html

Hours Monday through Thursday 0800 to 1130

and 1300 to 1530

U.S. Consulate

The Consular Section of the U.S. Embassy is on Entoto Avenue in

Addis Ababa.

Location Addis Ababa, Ethiopia

Mailing Address Entoto Avenue, P.O. Box 1014, Addis Ababa

Telephone Number 251-011-124-2424

3

U.S. Embassy in Addis Ababa

Museum

Grand

Market

Area

Hospital

Hospital

University

U.S.

Embassy

Grand

Palace

Development through

Cooperation Ave

St

Entoto Ave

Melekot

Haile

St

Wetherall

Belai Zeleke St

St

Patriot

Petros

St

Wave St

Wingate St

Eden

St

King George VI St

Russian St

Elizabeth

Queen

St

Tesema Abakemaw St

Gambia St

Ave

Desta Damtew Ave

Ave

Mekonnen

Aragay

St

Abebe

Sudan St

Field Marshal Smuts St

Africa Ave

To Airport

Jomo

Kenyatta

Ave

Zauditu St

Menelik II Ave

Itegue Taitu St

Colson St

Abune

Kurkume

River

Kechene

River

Bantyiketu River

N

Addis Ababa

Hospitals

Places of Interest

Educational

Institution

Grand Palace

4

Fax Number 251-011-124-2435

E-mail Address consaddis@state.gov, consacs@state.gov

Internet Address http://ethiopia.usembassy.gov/

Hours Monday through Thursday 0800 to 1130

and 1300 to 1530

GEOGRAPHY AND CLIMATE

Geography

Ethiopia is a landlocked country with boundaries from latitude

3N to 15N and from longitude 33E to 48E, enclosing an area of

1,127,127 square kilometers (435,186 square miles). Occupying

most of the Horn of Africa, the landmass of Ethiopia is roughly

three times the size of California. Ethiopia comprises two geo-

graphic areas: the cool highlands and the hot lowlands.

The Great Rift Valley divides the highlands into northern and

southern parts, and each has corresponding lowlands. The high-

lands in the northwest are rugged. Erosion has produced steep val-

leys that are in some places 1,600 meters (5,249 feet) deep and

many kilometers wide. In addition, the northwestern highlands

are subdivided by the valley of the Blue Nile.

The Great Rift Valley is the most significant geographic region in

Ethiopia. The valley is a physical example of the giant fault line

that runs from the Jordan Valley in the Middle East to the Zambezi

River’s tributary in Mozambique. The fault line diagonally bisects

the center of Ethiopia and splits the Ethiopian Highlands in half.

In Ethiopia, the northernmost part of the rift is marked by the

Danakil Depression, which is 115 meters (377 feet) below sea level

and one of the hottest places on earth. Also referred to as the Afar

Depression (it is located in Afar Region), the Danakil Depression

5

is a triangle-shaped basin that stretches into Eritrea. Water from

Ethiopia flows to the lowest point in Africa, Lake Asal in Djibouti.

Land Statistics

Total Area: 1,127,127 square kilometers

(435,186 square miles)

Water Area:

7,444 square kilometers (2,874 square miles)

Horn of Africa

Lake

Victoria

Mediterranean Sea

Red Sea

Persian Gulf

Gulf of Aden

Indian

Ocean

LEBANON

ISRAEL

JORDAN

IRAQ

KUWAIT

IRAN

SAUDI

ARABIA

U.A.E

QATAR

OMAN

YEMEN

EGYPT

LIBYA

CHAD

SUDAN

ETHIOPIA

ERITREA

DJIBOUTI

SOMALIA

KENYA

ADDIS

ABABA

UGANDA

TANZANIA

DEMOCRATIC

REPUBLIC OF

CONGO

CENTRAL

AFRICAN

REPUBLIC

RWANDA

BURUNDI

Northeast Africa

6

Coastline: 0 kilometers, 0 miles (landlocked)

Area Comparative:

Slightly less than twice the size of Texas

Central Coordinates: 0800N 03800E

Land Usage: Cultivated: 23%; Inhabited: N/A

Borders

Ethiopia has a total of 5,328 kilometers (3,311 miles) of continu-

ous land boundaries.

Direction Country Length

North Eritrea 912 km (567 mi)

East Djibouti 349 km (217 mi)

East Somalia 1,600 km (994 mi)

South Kenya 861 km (535 mi)

West Sudan 1,606 km (998 mi)

Total 5,328 km (3,311 mi)

Border Disputes

Eritrea

After Eritrea became independent in 1993, the government of

Ethiopia claimed the Eritrean areas of Badme and Zelambessa.

The border between Ethiopia and Eritrea had been determined

through treaties signed in the 1900s between the government of

Italy and Ethiopia’s former monarchy. The original maps were

written in three languages (Amharic, Italian, and English), and

the variation in the translations is the main point of contention

over the border. When translated into English, the maps written

in Italian and the maps written in Amharic use different terms for

the same features. These differences have led to confusion over

the physical border markers.

7

Most of the border between Eritrea and Ethiopia is indisput-

ably defined by rivers and tributaries. Treaties between Italy and

Ethiopia define the eastern portion of the border as 60 kilome-

ters (37 miles) from the coast and parallel to the Djibouti border.

There have been border disputes concerning the small villages of

Badme in the west and Tsorena and Zelambessa in the center. The

Tekeze River (also known as the Setit) runs along the western por-

tion of the border between Ethiopia and Eritrea and splits into two

segments just south of Badme. One leg of the river sharply turns

south and flows into Ethiopia; the other tributary flows north until

it connects to the Mereb River. Eritrea claims the original bor-

der treaties agree on an imaginary straight line drawn from the

apex of the fork in the Tekeze, through Badme, north to the Mereb

River. In contrast, Ethiopia claims the border from the split along

Barka

Mereb

Tekeze

Red

Sea

Akordat

Mitsiwa

Barentu

Badme

Mendfera

Axoum

Adwa

Adigrat

Alitenia

Senafe

Adi Keyh

Shire

Tsorena

Yirga

Shiraro

ASMARA

ERITREA

Ethiopia

National Capital

City

International Border

Disputed Border

Disputed Land

Disputed Land and Borders

8

the northbound tributary. Eritrea’s claim places Badme directly on

the border, but under the control of Eritrea, while Ethiopia’s claim

places Badme nearly 4.8 kilometers (3 miles) inside the Ethiopia

border and under Ethiopia’s control.

Similarly, the two countries disagree over the border near the

villages of Tsorena and Zelambessa, specifically with regard

to names of local tributaries. Local tribes have different lan-

guages and, therefore, different names for the tributaries that

run between Ethiopia and Eritrea. This makes it unclear which

streams are intended by the Treaty of 1902 to form the border.

According to Eritrea, the village of Tsorena is in Eritrea, just

north of the border, and Zelambessa is in Ethiopia, just south of

the border. Ethiopia claims that both towns are directly on the

border. The difference is a matter of a few miles, but results in a

loss of land for Eritrea.

In the east, the dispute over the border town of Bure is based on

disagreement over distance-measuring methods. Around Bure,

the treaty defines the border provisionally as running “parallel to

and at a distance of 60 kilometers from the coast,” an ambiguous

definition as it does not dictate how the 60 kilometers is to be

measured. The treaty’s recommendation that the border be more

precisely delineated was never fulfilled. The countries disagree on

where to start measuring 60 kilometers (37 miles) from the coast.

The difference is merely a mile, but it is a loss of land for Eritrea.

In 1998, a 2½-year border war began between the two countries,

and although hostilities ended under UN auspices, the border

is still in dispute. The UN established a 25-kilometer (15-mile)

Temporary Security Zone on the Eritrea side of the border and

established a military contingent, the UN Mission to Ethiopia and

Eritrea, to monitor the border.

9

Since 2002, neither Eritrea nor Ethiopia has been cooperative with

the border demarcation. A virtual demarcation now in place lists

43 points (and their coordinates) that outline the internationally

recognized border. Ethiopia has refused to recognize the virtual

demarcation. Due to the continued disagreement, maps of the bor-

der may vary. The 43 points are listed in Appendix F.

The Illemi Triangle

The Ethiopia/Kenya border was delimited in 1963. The border be-

tween Ethiopia and Sudan was delimited in 1902. The combined bor-

ders between Ethiopia, Sudan, and Kenya make up the area known as

the Illemi Triangle. The area covers nearly 14,000 square kilometers

(5,405 square miles) and is administered by Kenya, but claimed by

all three countries. The dispute over the territory stems from a series

of poorly worded colonial-era treaties written in an attempt to pro-

vide freedom of movement for the nomadic Turkana people of the

border region. The three countries have been too involved with other

priorities in the past couple of decades to resolve the issue.

Sudan

Ethiopian and Sudanese border farmers have long contested farm-

land delineation, particularly in Quara and Metema. In a meet-

ing between the Sudan and Ethiopia governments in late 2008,

Ethiopia allegedly ceded land to Sudan. Ethiopia has neither con-

firmed nor denied reports of Sudanese troops displacing Ethiopian

farmers. News of the new boundary settlement along the 1,600-ki-

lometer (994-mile) border surprised and angered many Ethiopians.

Bodies of Water

Rivers

Ethiopia has nine major rivers, each of which originates in the

highlands and flows through deep gorges into the surround-

10

ing lowlands. The Blue Nile (in Ethiopia called the Abbai or

Abay) is Ethiopia’s largest river and the largest contributor to the

Nile River Basin, which also includes the Baro-Akobo, Tekeze/

Atbara, and Mereb rivers. The Blue Nile and covers 33 percent

of the country, flowing through the northern and central parts

westward into Sudan. The Awash River is part of the Great

Rift Valley basin and flows east through the northern Great

Rift Valley. The river ends in saltwater lakes in the Danakil

Depression, the lowest point in Ethiopia (-125 meters [-410 feet]).

The southern Genale-Dawa and Wabe Shebelle Rivers are part

1950 Sudan Patrol Line

Lake

Turkana

1944 Blue Line

1938 Wakefield Line

1902 Maud Line

Kalemothia

Lokomarinyang

Kokuro

Todenyang

New

Township

Nakua

Kalam

SUDAN

ETHIOPIA

KENYA

Ilemi Triangle

City

International Border

Disputed Land

ADDIS

ABABA

SUDAN

KENYA

ETHIOPIA

Ilemi Triangle Red line, also known as the Wakefield Line, was es-

tablished by a joint Kenya-Sudan survey team in 1938. Blue line

was established in 1944 by the British Office for Foreign Affairs.

Sudanese patrol line was established unilaterally by Sudan in 1950.

11

of the Shebelle-Juba Basin and flow southeast into Somalia. The

Omo River empties into Lake Turkana.

Ethiopia’s large rivers and major tributaries are below 1,500

meters (4,921 feet). Most of Ethiopia’s other rivers are seasonal

with the highest levels occurring between June and August. In

the dry season, springs provide enough baseflow for small-

scale irrigation.

Lakes

Ethiopia has Great Rift Valley lakes, highland lakes, and crater

lakes. Most of Ethiopia’s largest lakes are in the Great Rift Valley.

Great Rift Valley lakes occupy the floor of the valley between the

northern and southern highlands. Lake Zway is the valley’s only

freshwater lake.

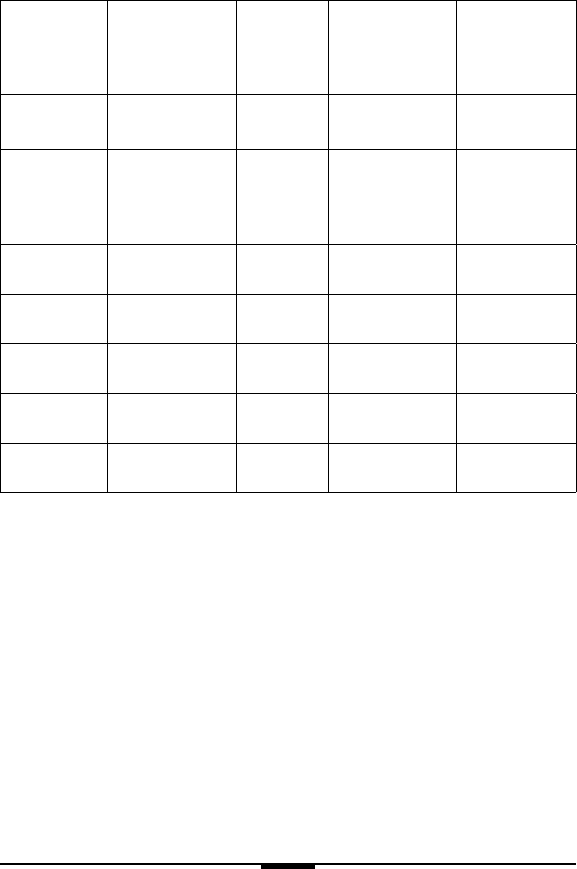

Major Great Rift Valley Lakes

Lake Area Elevation

Abaya 1,160 sq km (448 sq mi) 1,285 m (4,216 ft)

Chamo 551 sq km (213 sq mi) 1,235 m (4,052 ft)

Awasa 129 sq km (50 sq mi) 1,708 m (5,600 ft)

Zway 300 sq km (116 sq mi) 1,636 m (5,367 ft)

Abijata 205 sq km (79 sq mi) 1,573 m (5,160 ft)

Koka 250 sq km (97 sq mi) 1,590 m (5,217 ft)

Lake Tana (3,600 square kilometers [1,390 square miles] /1,788

meters [5,688 feet] elevation), the largest lake in Ethiopia, is lo-

cated in the northern highlands. It is the source of the Blue Nile

River and contains 37 islands. Heavy rainfall often causes water

levels in Lake Tana to rise significantly, creating concerns about

overflow. Lakes Hayq, Ardebo, and Ashengie are major highland

lakes located near the edge of the western escarpment of the Great

12

Rift Valley at altitudes between 2,000 and 2,500 meters (6,562

and 8,202 feet). Lake Ashengie is the largest of the three, covering

25 square kilometers (9.6 square miles) with a maximum depth of

20 meters (66 feet).

Several crater lakes (Bishoftu, Aranguade, Hora, Kilotes, and

Pawlo) are located at the northwestern edge of the Great Rift

Valley near the town of Debre Zeit at an altitude of nearly 1,900

meters (6,234 feet). The lakes lie in volcanic explosion craters pro-

duced 7,000 years ago.

Topography

Ethiopia’s varied landforms include rugged highlands, isolated val-

leys, dense forests, and hot lowland plains. So rugged is Ethiopia’s

terrain that it has served as a defense against invading armies, iso-

lating the country from the rest of the world. Ethiopia consists of

four physiographic regions: the high plateaus, the central highlands,

the lowlands, and the Great Rift Valley.

The high plateaus of Ethiopia are formidable natural barriers that

have physically set the country apart from its neighbors. At el-

evations generally between 1,800 and 3,000 meters (5,905 and

9,842 feet), the Ethiopian Plateau, which comprises two-thirds

of the country, consists of the northwest and southeast highlands.

Both contain several mountain peaks approximately 4,500 meters

(14,763 feet) above sea level. Erosion has produced steep valleys

that are in some places 1,600 kilometers (5,246 feet) deep and sev-

eral kilometers wide. Rapid streams in these valleys are unsuitable

for navigation. The southeast highlands are mostly flat and arid

(semi-desert). The northwest highlands are considerably more ex-

tensive and rugged; the valley of the Blue Nile divides these high-

lands into northern and southern sections.

13

The geologically active Great Rift Valley, which is susceptible to

earthquakes and volcanic eruptions, runs north and south separat-

ing the northwest and southeast highlands. It is dotted with lakes

and bounded on the east and west by escarpments. In the north,

the valley widens into the Awash River Basin, which contains the

Danakil Depression, a desert region 116 meters (380 feet) below

J

u

b

b

a

D

a

w

a

B

a

r

o

T

e

k

e

z

e

B

l

u

e

N

i

l

e

N

i

l

e

W

h

i

t

e

N

i

l

e

Indian

Ocean

Gulf of

Aden

Red

Sea

Lake

Turkana

Atbarah

Kibre

Mengist

Adwa

Nazret

Jijiga

Bonga

Dolo Bay

Dire

Dawa

Gonder

Mekele

Nekemte

Dese

Debre

Markos

Gore

Yirga 'Alem

Asela

Harer

Goba

Arba Minch

Jima

DJIBOUTI

ADDIS

ABABA

MOGADISHU

ASMARA

SAUDI

ARABIA

SAUDI

ARABIA

YEMENYEMEN

SUDANSUDAN

UGANDAUGANDA

KENYAKENYA

SOMALIASOMALIA

DJIBOUTIDJIBOUTI

ERITREAERITREA

44°

36°

4°

12°

Boundary not defined and in Dispute

5,000+

4,000-5,000

3,000-4,000

2,000-3,000

1,000-2,000

500-1,000

200-500

0-200

Elevation in Meters

Ethiopia

National Capital

Province Capital

City

International Border

Disputed Border

0

50

150

0

150 mi

50

100

100

200 km

Topography

14

sea level that runs parallel to the Red Sea and consists of salt lakes

and a major sinkhole, called the Kobar Sink.

Vegetation

The flora of Ethiopia varies with elevation and climate. In the low-

lands, vegetation is often dense and tropical, except in Danakil

Omo

W

a

b

e

S

h

e

b

e

l

l

e

J

u

b

b

a

D

a

w

a

W

a

b

e

S

h

e

b

e

l

l

e

B

a

r

o

B

l

u

e

N

i

l

e

T

e

k

e

z

e

B

l

u

e

N

i

l

e

N

i

l

e

W

h

i

t

e

N

i

l

e

Indian

Ocean

Gulf of

Aden

Red

Sea

Lake

Turkana

'

A

t

b

a

r

a

h

Kibre

Mengist

Adwa

Jijiga

Bonga

Dolo

Bay

Dire

Dawa

Gonder

Mekele

Nekemte

Dese

Debre

Markos

Gore

Yirga

'Alem

Asela

Harer

Goba

Arba Minch

Jima

KHARTOUM

DJIBOUTI

ADDIS

ABABA

MOGADISHU

ASMARA

SAUDI

ARABIA

YEMEN

SUDAN

UGANDA

KENYA

SOMALIA

DJIBOUTI

ERITREA

A

w

a

s

h

44°

36°

4°

12°

Boundary not defined and in dispute

Ethiopia

National Capital

City

International boundary

Steppe and desert

Tropical brush

Savanna

Upland grassland

Deciduous woodland

Tropical highland forest

0

50

150

0

150 mi

50

100

100

200 km

Vegetation

15

and the southeastern plains where only indigenous brush and

acacia trees live. There are thickly wooded hillsides, particularly

through the central highland elevations. In the highlands, bushes

and trees are generally scattered in small clusters.

Cross-country Movement

Much of Ethiopia is accessible only by air. Ethiopia’s rugged ter-

rain hinders most cross-country travel, even with four-wheel-drive

vehicles. Landmines also present significant danger. The center

of the country is covered by mountains and high plateaus that are

divided by deep gorges and steep valleys. Changes in elevation

can be from hundreds to thousands of feet. Most of the primary

roads run along the Great Rift Valley from northeast to southwest.

Ethiopia’s road development has increased in the past decade. Still,

driving four-wheel-drive vehicles with heavy-duty suspension is

recommended. Many of the roads are simply areas that cut across

the hard desert path. During periods of heavy rain, these roads be-

come impassable. The road system radiates in all directions from

the capital, Addis Ababa.

Urban Geography

Ethiopia’s urban centers are characterized by sprawling slums and

unsanitary conditions. The urban poor live in cramped kebeles

(urban villages) consisting of dilapidated shelters made of plas-

tered wooden walls and tin roofs. Fewer than half of all house-

holds in 10 current regional capitals have access to potable water

or access to latrines. Less than two-thirds of households in these

areas have solid waste collection service.

The capital city of Addis Ababa is surrounded by smaller cities on

the rail line and along major roads. The city is divided by eleva-

tion into two parts. The oldest, northern portion of the city, called

16

Arada, is centrally located. Arada has a public square, several

small markets, and Addis Ababa University. The second, more

contemporary part is Lower Addis Ababa, the commercial dis-

trict. It has hotels, government buildings, restaurants, shops, mu-

seums, a soccer stadium, and a railroad station. It is also the main

European and American business district.

Wealthy residential areas in Addis Ababa are southeast of the city

near Bole International Airport and southwest of the city near

Lideta Airport. The Bole International Airport is at the south-

eastern end of Bole Road. The most impoverished areas in Addis

Ababa are near the central business district. There are slums and

shantytowns in the north and northwest at Addis Ketema.

Addis Ababa, located below the Entotto Mountains, covers 222

kilometers (137 miles) and is the largest and most populated city

in Ethiopia (2.25 million). The mix of towering mountains and the

deep chasms they create adds to the diversity of the climate and

vegetation in the area north of Addis Ababa.

Addis Ababa’s architecture is a mix of old buildings in the Italian

style, modern offices and apartments, Western-style villas, and

mud-walled tin-roof dwellings. Streets are built on a grid pattern

running north-south and east-west. Seven diagonal roads con-

nect to seven circular plazas on the city’s transportation network.

Ethiopia’s government renamed all the streets in Addis Ababa in

2005. Churchill Avenue, the main north-south corridor in Addis

Ababa, was renamed Gambia Street. Gambia Street connects

Arada to the southern portion of Addis Ababa. The roads in Addis

Ababa are busiest at dusk, when cattle and goats are driven from

fields to their owners’ homes in the city.

Merkato, often called the Grand Market Area, is east of Arada and

is potentially the largest market in Africa. Merkato is busiest on

17

Saturdays, when farmers, merchants, and tourists from all over the

country are most likely to be there. Most of the foreign embassies,

including the U.S. Embassy, are located northeast of Arada along

Entoto Avenue.

Dire Dawa is 20 kilometers (12 miles) off the road to Harer in

eastern Ethiopia. From Djibouti, Dire Dawa is a major city along

the route to Addis Ababa. The city has a strong French influence

due to its proximity to the former French colony of Djibouti. The

wide boulevards and the infrastructure in Dire Dawa were mod-

eled after large French cities, which makes Dire Dawa very differ-

ent from all other cities in Ethiopia.

Climate

Ethiopia’s temperatures range from equatorial desert to cool

steppe. In Ethiopia, the southwest receives the most rainfall, with

Women Shopping at Market

18

an average annual rainfall of 2,200 millimeters (87 inches). The

amount of rainfall decreases to less than 200 millimeters (8 inch-

es) throughout the Danakil Depression, the lower Awash River

Basin, and eastern Ogaden. Highland plateaus, which cover more

than half of Ethiopia, are surrounded by arid and semi-arid low-

lands. The highlands receive large amounts of rain and serve as

the watershed for the surrounding lowlands.

Ethiopia has three general climatic zones: tropical in the south

and southwest, cold to temperate in the highlands, and arid to

semi-arid in the northeastern and southeastern lowlands.

■ The tropical zone, below 1,800 meters (5,905 feet), has an av-

erage annual temperature of 27°C (81°F) and an average an-

nual rainfall of less than 500 millimeters (19.7 inches).

■ The subtropical zone, which includes most of the highland

plateau and lies between 1,800 and 2,400 meters (5,905

and 7,874 feet) above sea level, has an average tempera-

ture of 22°C (72°F) and an annual rainfall ranging from

500 to 1,500 millimeters (19.7 to 59 inches).

■ Above 2,400 meters (7,874 feet) is a temperate zone with an

average temperature of 16°C (61°F) and an annual rainfall be-

tween 1,200 and 1,800 millimeters (47 and 71 inches). The

main rainy season occurs from mid-June to September, fol-

lowed by a dry season that may be interrupted in February or

March by a short rainy season.

■ The eastern lowlands are much drier with a hot, semi-arid

climate. Rainfall occurs during April, May, July, and August,

and the hottest months are February and March.

Nighttime temperatures may fall to near or below freezing in the

mountains, particularly during the dry season. Occasionally, snow

may fall on the highest peaks, but there are no permanent snowfields.

19

D

A

Y

S

D

A

Y

S

o

F

o

F

TEMPERATURE

TEMPERATURE

PRECIPITATION

PRECIPITATION

ADDIS ABABA

ELEVATION: 7,727 FT

GONDER

ELEVATION: 6,513 FT

Extreme High

Average High

Average Low

Extreme Low

Extreme High

Average High

Average Low

Extreme Low

Snow

Rain

Snow

Rain

0º

20º

40º

60º

80º

100º

DNOSAJJMAMFJ

0

5

10

15

20

25

30

DNOSAJJMAMFJ

0

5

10

15

20

25

30

DNOSAJJMAMFJ

0º

20º

40º

60º

80º

100º

DNOSAJJMAMFJ

Addis Ababa and Gonder Weather

20

D

A

Y

S

D

A

Y

S

o

F

o

F

TEMPERATURE

TEMPERATURE

PRECIPITATION

PRECIPITATION

HARER

ELEVATION: 6,155 FT

JIMA

ELEVATION: 5,499 FT

Extreme High

Average High

Average Low

Extreme Low

Extreme High

Average High

Average Low

Extreme Low

Snow

Rain

Snow

Rain

0º

20º

40º

60º

80º

100º

DNOSAJJMAMFJ

0

5

10

15

20

25

30

DNOSAJJMAMFJ

0

5

10

15

20

25

30

DNOSAJJMAMFJ

0º

20º

40º

60º

80º

100º

DNOSAJJMAMFJ

Harer and Jima Weather

21

Precipitation

In western Ethiopia, it can rain anytime between April and

September, but the heaviest rains fall during July and August.

Eastern Ethiopia has a short wet period from April to May and

heavy rains in July and August. The Great Rift Valley has an aver-

age annual rainfall of 600 millimeters (23.6 inches); half this rain-

fall occurs between July and September. The western foothills of

the rift escarpment experience an average annual rainfall of 800

to 1,000 millimeters (31.5 to 39.4 inches).

Monsoon winds blow west to southwest during the rainy season

(winds blow northeast during the dry season). More than 1,000

millimeters (40 inches) of rain falls in the highlands, and as much

as 1,500 to 2,000 millimeters (60 to 80 inches) of rain falls in

the western parts of the country. Thunderstorms are frequent in

the western parts of the country, occurring almost daily during

the rainy season; throughout the region, there are more than 100

thunderstorms a year.

Phenomena

Intense rainfall causes flooding along the Awash River and in the

lower Baro-Akobo and Wabe-Shebelle river basins, damaging crops

and infrastructure. Dikes have been built as a temporary measure.

Droughts are common and are occurring with increasing frequen-

cy. Ethiopia has had 30 major droughts in the past 9 centuries; 13

were severe, affecting hundreds of thousands of people.

Environment

Ethiopia’s long history of agricultural productivity has flourished

from fertile, volcanic soils. However, drought, overgrazing, defor-

estation, and poor agricultural practices have begun to erode the

22

soil. Despite the erosion, agriculture accounts for 40 percent of

Ethiopia’s GDP and 90 percent of its export earnings; the coun-

try’s chief export is coffee.

Major environmental issues in Ethiopia are deforestation, over-

grazing, soil erosion, desertification, water pollution, and urban air

pollution. In the central highlands, population growth, increased

crop cultivation, and increased livestock grazing cause deforesta-

tion and soil erosion. In the south and southwest, deforestation is

the result of resettlement, commercial farming, and fire. Despite

repeated soil and water conservation campaigns, significant

amounts of productive soil are lost every year to water and wind

erosion. As Ethiopia’s population increases, the nation relies more

on its forests for fuel, hunting, agriculture, and housing construc-

tion, all of which accelerates deforestation.

Throughout Ethiopia, wetlands are used for livestock grazing,

particularly during the dry season. In recent decades there has

been a noticeable change in the wetland’s characteristics, caused

by livestock increases, fodder shortages, and expanding agricul-

ture demands. Some wetlands have been transformed into rough

grazing land.

Ethiopia’s poor industrial and domestic waste disposal policies

are causing water pollution in urban centers such as Addis Ababa,

Mojoo, and Debre Zeit. Toxic substances from sugar, textile, and

tannery factories are dumped into rivers. Organic waste also con-

taminates Ethiopia’s water.

Air quality has sharply declined in Addis Ababa and other major

urban centers in Ethiopia because of an increase in motor vehicle

use. Ethiopia developed the Conservation Strategy of Ethiopia

(CSE) in 1989 and began seriously addressing environmental

problems in the early 1990s, implementing The Environmental

Policy of Ethiopia in 1997.

23

The area thought to be highest in mineral potential is in the west

and southwest, particularly in Wollega, Illubabor, and Kaffa; how-

ever, the area is largely inaccessible because much of it is cov-

ered by rain forest. Exploration for petroleum was carried out with

some success in the Bale region.

Hydroelectric power has great potential for the generation of elec-

tricity in Ethiopia. Several plants are already in operation along

the Awash River. Developers are planning to put additional sites

with both geothermal power provision and irrigation potential

along the Blue Nile River.

INFRASTRUCTURE

Transportation

General Description

Ethiopia’s transportation sector is deficient: many towns lack ac-

cess to all-weather roads; its commercial rail service infrastruc-

ture is negligible; and most of its airfields have unpaved runways

that are vulnerable to weather damage. Ethiopia has no direct

access to maritime port facilities and must rely on Djibouti and

Somalia port facilities to handle its vessel traffic as Eritrea ports

are not open to Ethiopia. Public transportation is unpredictable

and dangerous.

Roads

Ethiopia has 42,429 kilometers (26,364 miles) of roads, of which

5,515 kilometers (3,427 miles) are paved. As of 2007, 64 percent of

asphalt roads were in good condition. More than half the country’s

gravel and rural roads are in poor condition. On average, a villager

must travel 13 kilometers (8 miles) to reach an all-weather road.

The Ethiopia Roads Authority (ERA) is working to expand, reha-

24

bilitate, and upgrade road conditions under Phase III of the Road

Sector Development Program. ERA expects the road network to

measure 135,554 kilometers (84,230 miles) upon completion.

During the rainy season (June to September), roads may become

impassable due to flooding. Ethiopia experiences numerous earth-

quakes and volcanic eruptions, some of which may affect road

J

u

b

b

a

D

a

w

a

B

a

r

o

T

e

k

e

z

e

B

l

u

e

N

i

l

e

N

i

l

e

W

h

i

t

e

N

i

l

e

Indian

Ocean

Gulf of

Aden

Red

Sea

Lake

Turkana

Mitsiwa

Assab

Kibre

Mengist

Adwa

Nazret

Jijiga

Bonga

Dolo Bay

Dire Dawa

Gonder

Mekele

Nekemte

Dese

Debre

Markos

Gore

Yirga 'Alem

Asela

Harer

Goba

Arba

Minch

Jima

KHARTOUM

DJIBOUTI

ADDIS

ABABA

MOGADISHU

SANAA

ASMARA

SAUDI

ARABIA

YEMEN

SUDAN

UGANDA

KENYA

SOMALIA

DJIBOUTI

ERITREA

Boundary not defined and in Dispute

Ethiopia

National Capital

Province Capital

City

Primary Road

Railroad

Province Border

International Border

Disputed Border

0

50

150

0

150 mi

50 100

100

200 km

Transportation Network

25

travel. Roads are economically vital to counter the lack of suffi-

cient rail lines and domestic seaports. The road network transports

95 percent of passenger and freight traffic.

Pedestrians tend to cross the street at inappropriate places or walk

along roads, paying no attention to traffic. Drivers should watch

for stray livestock, wild animals, potholes, unlit vehicles, and false

checkpoints. Outlying roads do not have lanes, road markings, or

safety lights; road conditions are poor.

Driving is dangerous outside urban areas. Aggressive driving,

armed robbery, banditry, carjacking, and speeding are serious

problems. Tactics used by armed groups and terrorists include using

false checkpoints, using explosive devices, and ambushing vehicles.

Donkey Roaming the Streets

26

Driving along the roads near Ethiopia’s border regions with Eritrea,

Kenya, Somalia, and Sudan is particularly dangerous, as the threat

potential may be higher in these locations than it is elsewhere.

Landmines may pose a danger for drivers traveling on dirt roads

in remote areas, particularly along the security zone separating

Eritrea and Ethiopia. Incidents generally involve newly laid mines

on recently cleared roads.

Vehicles travel on the right side of the road. Stuck and abandoned

vehicles are commonplace during the rainy season. In many ar-

eas, roads may be passable only with four-wheel-drive vehicles.

Accident rates are high.

Taxis and car hire services are available in urban areas. Blue

and white shared taxis offer cheaper fares; neither use meters.

Instead, fares are negotiated; passengers should agree on a price

before departing. Private and public bus service is available

throughout Ethiopia.

Rail

Ethiopia has one railroad, which uses narrow gauge (1 meter [3.2

feet]) line. It is 681 kilometers (423 miles) long and connects

Addis Ababa with the port of Djibouti. Ethiopia and Djibouti own

and operate the line, which is in bad condition. Hoping to reduce

its reliance on Djibouti, Ethiopia reached an agreement with

Sudan in 2001 to build a rail link to Port Sudan (1936N 03714E).

The project will require a substantial amount of time and money

(US$1.5 billion) to complete.

Travelers should not travel by rail, as terrorists sabotage, bomb,

and derail trains. Train schedules are unreliable and delays are

27

frequent. Rail bridges between Dire Dawa and Djibouti are also

in need of repair.

Between 700,000 and 800,000 passengers and up to 250,000

tonnes (275,577 tons) of freight transit the railroad per year. The

rail line is not important to Ethiopia’s economy, as only a minor

portion of passenger and freight traffic uses the system. Light-rail

or subway services are not available.

Air

Primary Airfields

Airport

Name Coordinates Elevation

Runway

Length x

Width

meters (feet) Remarks

Arba Mingh 0602N 03735E 1,187 m

(3,894 ft)

2,795 x 47

(9,170 x 154)

Asphalt

Asosa 1001N 03435E 1,561 m

(5,121 ft)

1,950 x 46

(6,398 x 151)

Asphalt

Axum 1408N 03846E 2,108 m

(6,916 ft)

2,400 x 45

(7,874 x 148)

Asphalt

Bahir Dar 1136N 03719E 1,821 m

(5,974 ft)

3,000 x 61

(9,843 x 200)

Concrete, as-

phalt, and bi-

tumen-bound

crushed rock

Bole Intl 0858N 03847E 2,334 m

(7,657 ft)

3,800 x 45

(12,467 x 148)

Asphalt

3,700 x 45

(12,139 x 148)

Asphalt

Dire Dawa

Intl (joint

civil and

military)

0937N 04151E 1,167 m

(3,829 ft)

2,679 x 45

(8,789 x 148)

Asphalt

28

Airport

Name Coordinates Elevation

Runway

Length x

Width

meters (feet) Remarks

Gambella 0807N 03433E 540 m

(1,772 ft)

2,514 x 45

(8,248 x 148)

Concrete

Gode 0556N 04334E 254 m

(833 ft)

2,288 x 35

(7,507 x 115)

Concrete, as-

phalt, and bi-

tumen-bound

crushed rock

Gonder 1231N 03726E 1,994 m

(6,542 ft)

2,780 x 45

(9,121 x 148)

Asphalt

Jima 0739N 03648E 1,703 m

(5,587 ft)

2,000 x 50

(6,562 x 164)

Asphalt

Lalibella 1158N 03858E 1,958 m

(6,424 ft)

2,435 x 53

(7,989 x 174)

Asphalt

Lideta

(military)

0900N 03843E 2,362 m

(7,749 ft)

1,170 x 20

(3,389 x 66)

Asphalt

Mekale 1328N 03932E 2,257 m

(7,405 ft)

3,604 x 43

(11,824 x 141)

Asphalt

International airlines with regular service to Addis Ababa include

Air France, British Airways, Djibouti Airlines, Kenya Airways,

and Lufthansa. Ethiopia Airlines provides domestic and interna-

tional flights. Its domestic routes cover all the main population

centers. International direct routes cover many African, Asian,

European, and Middle Eastern cities. Washington, DC, is Ethiopia

Airlines’ only U.S. destination

.

Ethiopia has 84 airfields, 15 of which were paved as of 2007.

Three of the paved runways are longer than 3,047 meters

(10,000 feet); 21 unpaved runways are shorter than 914 meters

(3,000 feet)

.

29

Aircraft attempting to land on or take off from many of these run-

ways frequently have to navigate around obstacles on runways,

terrain features, birds, livestock, and wildlife.

The Ethiopia Civil Aviation Authority is responsible for establishing air

transportation regulations. The U.S. Federal Aviation Administration

has assessed Ethiopia’s Civil Aviation Authority as being compliant

(Category 1) with International Civil Aviation Organization’s safety

standards. The Ethiopian Customs Authority is responsible for pro-

tecting air travel by screening cargo, baggage, and travelers.

Maritime

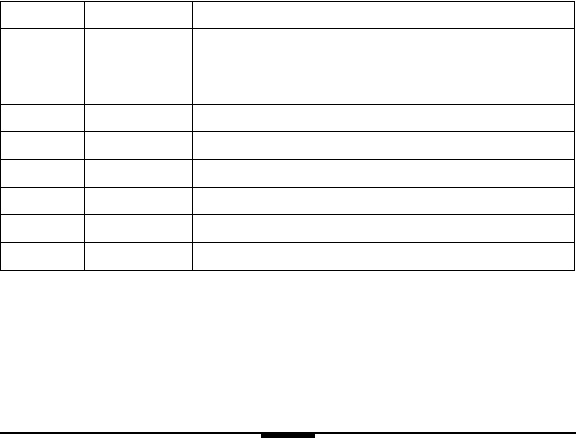

Primary Ports

Port Name,

Coord.

Berthing

Anchor

Depth

Pier Depth Remarks

Djibouti

(Djibouti),

1136N 04308E

Vessels more

than 152 m

(500 ft) in

length

6.4–7.6 m

(21–25 ft)

6.4–7.6 m

(21–25 ft)

Channel

depth:

9.4–10.7 m

(31–35 ft)

Oil terminal:

9.4–10.7 m

(31–35 ft)

Berbera

(Somalia),

1027N 04501E

Vessels more

than 152 m

(500 ft) in

length

11–12.2 m

(36–40 ft)

9.4–10.7 m

(31–35 ft)

Channel

depth:

9.4–10.7 m

(31–35 ft)

Oil terminal:

7.9–9.1 m

(26–30 ft)

Sudan

(Sudan)

1936N 03714E

Vessels more

than 152 m

(500 ft) in

length

20.1–21.3 m

(66–70 ft)

7.9–9.1 m

(26–30 ft)

Channel

depth:

23.2+ m

(76+ ft)

Oil terminal:

9.4–10.7 m

(31–35 ft)

Ethiopia has no significant navigable waterways; most rivers are

seasonal; the water levels are highest between June and August.

30

Boulders, small islands, and other obstacles make navigating riv-

ers extremely difficult, even with light watercraft.

Most large lakes are navigable by light watercraft. Lake Shala is

the deepest, at 226 meters (741 feet).

Ethiopia’s largest lake, Lake Tana, contains 37 islands. Ferry

services to these islands is available, and the lake is navigable

year-round

.

Ethiopia had a fleet of nine merchant vessels as of December 2008:

one roll-on/roll-off vessel and eight cargo ships. Dugout canoes,

inflatable rafts, kayaks, and tankwa (papyrus boats) are common

sights in navigable lakes and rivers.

Utilities

Electricity

Ethiopia has one of the world’s lowest rates of access to modern en-

ergy technology, and relies primarily on wood, crops, and animal

waste to supply its energy needs. According to the World Bank,

12 percent of Ethiopians have access to electricity (2 percent of

rural residents and 86 percent of urban residents). Hydropower is

the backbone of the energy sector, and as such, energy is in short

supply during droughts.

Eight hydropower dams account for more than 85 percent of

Ethiopia’s 767 megawatts of grid-based generating capacity. Six

of the eight plants were built prior to 1988; the oldest was built

in 1964. Five additional hydropower sites with a combined ca-

pacity of 3,125 megawatts are under construction. Two of those

sites, Tekeze (300 megawatts) and Gilgel Gibe II (480 mega-

watts), are expected to double the national capacity. The aim is

31

to increase capacity to 9,000 megawatts by 2018, with surplus

power exported to neighboring Kenya, Djibouti, and Sudan.

Another goal is to improve the efficiency of existing energy re-

sources, since energy loss is 19.5 percent compared to the inter-

national average of 13.5 percent.

Electricity in Ethiopia is delivered in 220 to 240 or 110 volts

(depending on location), alternating at 50 cycles per second.

Outlets accept three types of plugs: type D with three round

pins, type J with three round pins (one offset), and type L with

three parallel pins.

Water

Ethiopia has one of the lowest water supply and sanitation cover-

age levels in the world. Budget resources combined with other

aid have not been sufficient to improve coverage, and user fees

for service are often too low to provide for adequate maintenance

of facilities.

Ethiopia’s water resources are unevenly distributed. More than 80

percent of Ethiopia’s surface water comes from one of the four

river basins in the west and southwest regions: (Abay [Blue Nile],

Tekeze, Baro-Akobo, and Omo-Gibe). River basins in the east and

central regions make up the remainder of Ethiopia’s surface water,

but this region has 60 percent of the nation’s population. Coverage

reached 52.5 percent in 2007 (82 percent urban and 46.5 percent

rural), up from less than 30 percent in 2002.

Many people travel long distances to search for water from bore-

holes, springs, ponds, streams, and rivers. Water from rivers and

other undeveloped sources is often unsafe and unreliable. Even

in urban centers, the supply and quality of water is inadequate

and unreliable.

32

Sanitation

Ethiopia’s sanitation infrastructure is nearly nonexistent.

According to the World Health Organization, 8 percent of the ru-

ral population has access to improved sanitation coverage, 2 per-

cent has access to shared coverage, 16 percent has access to unim-

proved coverage, and 74 percent has no coverage, leaving people

to use open areas (open defecation). Urban residents fare better at

27 percent improved, 35 percent shared, 27 percent unimproved,

and 11 percent no coverage.

The quality of facilities (mostly latrines) is poor. More than 50

percent are considered structurally unsafe, and 50 percent are un-

hygienic. Public sanitation services such as public toilet facilities,

sludge (seepage) collection, and related environmental health ser-

vices are generally inadequate and do not meet demands. Addis

Ababa is the only town with a sewerage system, but it is small.

Communication

Ethiopia’s government controls the communication assets in

Ethiopia. All television and radio stations are state owned, but two

private commercial radio stations have run broadcast tests, as of

late 2007. Communication assets include radio, television, internet,

satellite, print publications, fixed and mobile telephones, and post

offices. Microwave radio; open-wire; HF, VHF, UHF radio commu-

nication services; and satellite contribute to the domestic telecom-

munications system. The fixed-line telephone system is adequate,

but travelers should expect service interruptions. Cellular services

are expanding, but they are currently only available in urban centers

.

Ethiopia’s laws provide for freedom of expression and press, but

government actions against individuals, organizations, and me-

dia limit this freedom. All media outlets practice self-censorship

33

to avoid government intimidation, fines, confinement, or forced

closure. Foreign and private media is also pressured to practice

self-censorship. Such actions of pressure include harassment,

threats, physical abuse, prosecution, and restricting journalists’

access to information. The government also monitors internet ac-

tivities, particularly those of journalists, editors, and publishers.

Ethiopia’s Ministry of Information occasionally denies press ac-

creditations to journalists.

Radio

Ethiopia has nine radio stations: eight AM stations and one short-

wave (SW) station (as of 2005). Radio Ethiopia, Radio Fana, and

Voice of Tigray Revolution are three of Ethiopia’s main AM, FM,

and SW radio stations. Broadcast languages include Oromigna

(Afan Oromo), Afar, Amharic (Amarigna), Arabic, English,

French, Somali (Somaligna), and Tigrigna. Sheger Radio and

ZAMI are private commercial radio stations. Sheger broadcasts

music and entertainment programs, while ZAMI broadcasts news

and talk shows.

Voice of America (VOA), BBC World Service Radio, and Radio

France Internationale (RFI) are international broadcasts avail-

able through shortwave radio. VOA broadcasts many programs

in Oromigna, Amharic, English, and Tigrigna. A variety of pro-

grams and stations are also available in English on BBC Radio.

RFI broadcasts programs in English and French through SW radio

and satellite. Frequencies vary according to the time of day.

Radio is a very significant medium because much of the popu-

lation is illiterate and/or has limited access to electricity, or is

unable to afford television. Ethiopia has 184 radios per 1,000 in-

habitants (2001)

.

34

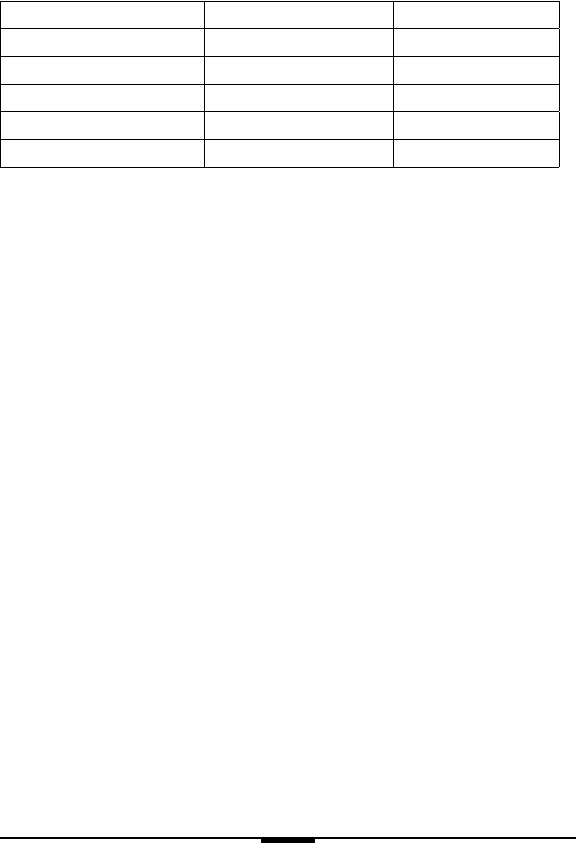

Major Stations Programming

Radio Ethiopia (684 AM, Metu; 855

AM, Harer; 873 AM, 990 AM, 97.1

FM, Addis Ababa)

N/A

Radio Fana (1080 AM, 98.1 FM, 6110

SW, 6940 SW, 7210 SW, Addis Ababa,

Afar, Oromia, Somali)

Entertainment, infor-

mation, news, talk

BBC Radio (6005 SW, 7375 SW, 9410

SW, 9750 SW, 11945 SW, 12035 SW,

15420 SW, 17640 SW, 21470 SW)

Business news,

entertainment, music,

news, sports, talk

Radio France Internationale (7315

SW, 9790 SW, 9805 SW, 11700 SW,

11995 SW, 13680 SW, 15605 SW,

21620 SW)

Information, music,

news, sports

Voice of America (9320 SW, 9485 SW,

9860 SW, 11520 SW, 11675 SW, 11905

SW, 13870 SW)

Entertainment, music,

news, sports, talk

Voice of Tigray Revolution (5950 SW,

5980 SW, 6170 SW, 9650 SW)

N/A

Television

Ethiopian Television (ETV) is the only domestic television net-

work; it is state owned.

Broadcasts are in Amharic, English, and

other local languages. Programs offered include films, documen-

taries, talk shows, news, and music TV. ETV Channel 1 broad-

casts 8 hours per day Monday through Friday and more than 16

hours on weekends. ETV Channel 2 is Ethiopia’s only regional

free-to-air channel; it is located in Addis Ababa.

Satellite television from South Africa and from ArabSat satel-

lite service providers is available, but only the elite can afford

35

it. Many Ethiopians cannot even afford to purchase a television.

Satellite service is available by subscription. BBC World, CNN,

MTV, SABC, and Sky TV are satellite channels. Four percent of

Ethiopian households own a television, according to the World

Bank (as of 2006).

Primary Television Stations Location

ETV, Channel 1 National

ETV, Channel 2 Addis Ababa

Telecommunication

Ethiopian Telecommunications Corporation (ETC), a tele-

communications monopoly, is a state-owned company offer-

ing fixed and wireless telephone services. ETC also offers in-

ternet service through its internet service provider, Ethiopian

Telecommunications Agency (ETA). The current backbone infra-

structure uses microwave, open-wire, radio, and VSAT technology.

The telephone system is inadequate. Ethiopia has one of the lowest

teledensities in Africa. One percent of Ethiopians subscribe to land-

line telephone services, and less than 2 percent use mobile phones.

ETC’s goal is to expand the telecommunications infrastructure to

rural areas through digital, satellite, wireless, and fiber-optic tech-

nologies. Major obstacles to telecommunication expansion in rural

areas are high initial costs, geography, and remoteness. Telephone

service interruptions are common, particularly during the rainy sea-

son. Pay phones are available in urban centers.

ETC also offers cellular phone service using GSM technology. SMS

(text messaging) is available. ETC has roaming agreements with

numerous international companies in Africa, the Americas, Asia,

Europe, and the Pacific. Other roaming partners include U.S. ser-

vice providers AT&T and T-Mobile USA. Network coverage is

36

available in Ethiopia’s large urban centers, but is limited or absent

elsewhere. Satellite phones are more reliable, but they are expensive.

Ethiopia Telecommunication Statistics

Total telephone subscribers (2007) 2,088,600

Telephone subscribers per 100 inhabitants 2.5

Main telephone lines 880,100

Main telephone lines per 100 inhabitants 1

Mobile users 1,208,500

Internet

Internet access is available mainly in Addis Ababa, but is also avail-

able elsewhere. Connectivity is slow and disruptions are frequent.

The public accesses the internet at internet cafes, public libraries,

schools, and universities. Internet access is available through one

internet service provider: the state-owned company ETC.

Technologies such as VSAT, dial-up, and DSL are available; dedi-

cated internet connections are not available. Satellite internet is

not available for personal use. A Chinese telecom company is

helping ETC upgrade its network with 3G technologies, which

will include wireless internet capabilities.

ETC and the ETA control all access to the internet. People can

generally express their views through the internet, but there are

strict limitations. There are reports that the government monitors

and blocks political opposition websites, diaspora group activity,

news sources, domestic online magazines, human rights group

activity, and websites that criticize the government. Popular blog-

ging websites are also blocked. The ETA requires internet cafes

to record the personal information of individual users along with

web logs; lists go to law enforcement.

37

Ethiopia Internet Statistics

Total Internet hosts (2008) 128

Hosts per 10,000 inhabitants (2008) <1

Users (2007) 290,850

Users per 100 inhabitants (2007) 0.35

Total number of personal computers (PCs) (2007) 531,840

PCs per 100 inhabitants (2007) 0.64

Internet broadband per 100 inhabitants (2007) 0

Newspapers and Magazines

Major English-language daily newspapers are Addis Zemen, the

Daily Monitor, and the Ethiopian Herald. Addis Zemen and the

Ethiopian Herald are state-owned newspapers; Addis Admass,

Addis Fortune, Addis Tribune, Capital, and the Daily Monitor are

privately owned. Addis Fortune and Capital are business news-

papers. Helm is a quarterly English-language Ethiopian publi-

cation focusing on art, culture, entertainment, and fashion. The

Sub-Saharan Informer is a weekly English-language Pan-African

newspaper that is available in Ethiopia.

The International Herald Tribune, Newsweek, and Time are inter-

national publications that are available in Addis Ababa. Other inter-

national publications include English- and French-language news-

papers that are available at hotels and newsstands. International

publications are available. Finding newspapers and other publica-

tions printed in English outside Addis Ababa may be difficult be-

cause of the low literacy rate and the remoteness of many areas.

Publication Politics Lang. Freq. Web Address

Addis Admass N/A Amharic Weekly www.addisadmass.com

Addis Fortune N/A English Weekly www.addisfortune.com

38

Publication Politics Lang. Freq. Web Address

Addis Tribune N/A English Weekly www.addistribune.com

Addis Zemen Pro-govt Amharic Daily N/A

Capital N/A English Weekly www.capitalethiopia.com

The Daily

Monitor

N/A English Daily N/A

The Ethiopian

Herald

Pro-govt English Daily N/A

The Reporter N/A Amharic Biweekly

www.ethiopianreporter.com

(Amharic version)

English en.ethiopianreporter.com

(English version)

Postal Service

The official name of the postal service is Ethiopian Postal Service.

The postal service provides postbox rentals, courier services, and

money orders. Ethiopia had 1,387 post offices as of 2006. Fewer

than 1 percent of the population has home delivery. In urban areas,

mail delivery and collection occurs twice per day; it averages five

times per week in rural areas. The postal system is reliable. DHL,

EMS, and TNT provide international delivery services; FedEx

and UPS contract services through domestic couriers.

Satellites

Ethiopia has access to three Intelsat satellite earth stations: one

in the Atlantic Ocean and two in the Pacific Ocean. The satellite

systems are for voice communications, radio, internet, and televi-

sion broadcasts. Most of Ethiopia is rural and has no telephone

landlines. There are no connections to submarine cables because

Ethiopia is landlocked. Ethiopia’s geography and the remoteness

of many areas are also obstacles for laying underground cables.

39

CULTURE

Statistics

Population 85,237,338 (July 2009 est.)

Population growth rate 3.21% (2009 est.)

Birth rate 43.66 births/1,000 population (2009

est.)

Death rate 11.55 deaths/1,000 population (July

2009 est.)

Net migration rate -0.02 migrant(s)/1,000 population

(2009 est.)

Life expectancy at birth Total population: 55.41 years

Male: 52.92 years

Female: 57.97 years (2009 est.)

Population age structure 0 to 14 years: 46.1%

15 to 64 years: 51.2%

65 years and older: 2.7% (2009 est.)

Date of the last census A population and housing census was

conducted in 2007

Population Patterns

Ethiopia is predominantly rural. According to the 2007 census, 84

percent of Ethiopia’s population lives in rural areas. Nearly 37 per-

cent (27.1 million) of the population lives in the regions of Oromia,

which is the largest state in Ethiopia. The next largest populations

are in the states of Amhara with 23 percent (17.2 million); Southern

Nations, Nationalities, and Peoples Region (SNNP) with 20 per-

cent (15 million); Somali 6 percent (4.4 million); and Tigray with

5.8 percent (4.3 million). Addis Ababa, the capital city, accounts

for only 3.7 percent (2.7 million) of the population. The remaining

regions each represent less than 9 percent of the population.

40

Population density is highest in the highlands, which run through

central Ethiopia along the Great Rift Valley and stretch north to

the border with Eritrea. The highlands have a population density

of 65 people per square kilometer (169 per square mile) according

to the 2007 census. Urban settlements cover less than 0.5 percent

of Ethiopia’s land area. Urban population density is 2,820 people

per square kilometer (7,306 per square mile)

. Addis Ababa has

the highest population density, with more than 5,100 people per

square kilometer (13,300 per square mile).

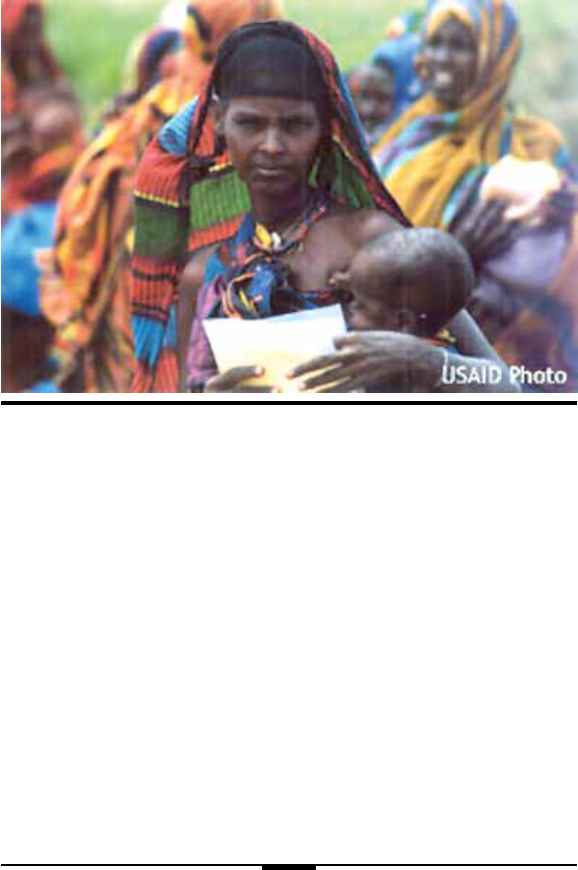

Internal displacement is significant. Ethnic clashes and regional

conflicts force many to seek shelter elsewhere in Ethiopia. Conflict

between Ethiopia and Eritrea has displaced many Ethiopians, who

have not yet resettled. Displacement to and from neighboring coun-

tries is substantial. Refugees from Eritrea, Somalia, and Sudan

are seeking safety in Ethiopia. Nearly 15,000 Ethiopian refugees

Adigudom

Adishehu

Adishehu

Chelena

Bora

Dela

Samre

Adi

Zeyla

Guya

Abi

Adi

Edaga Arbi

Mahibere

Degu

Abakh

Adwa

Axum

Rama

Gerehusernay

Enticino

Yeha

Dibdibo

Nebelet

Edaga Hamus

Adigrat

Sinkata

Hawzien

Wukro

Southern

Zone

Eastern

Zone

Central

Zone

Western

Zone

Zala Ambesa

Bizet

Adi

Haregay

Inde

Silase

Indabaguna

May Tsebri

Adi

Goshu

Zeben

Gedena

Sherara

Dansha

Baeker

Humera

Bereket

Afar

Region

Amhara

Region

To

Gonder

Mekele

SUDAN

ERITREA

Ethiopia/Eritrea Border Region

Regional capital

Zonal capital

Wereda capital

Town

Displaced camp

Movement of

displaced

Primary road

All weather road

Dry weather road

International border

Regional border

Zonal border

Displaced area

Displaced Popluation

41

are reported to be living in Kenya as of 2007. Between 200,000

and 250,000 Ethiopians are refugees. Most are in the Gambella,

Oromiya, and Somali regions, which also suffer from ethnic con-