Jennifer Arenson Yaeger Foundations of Reading Study Guide 2018

2

Table of Contents

OVERVIEW OF THE TEST AND RESOURCES FOR PREPARATION 3

FOUNDATIONS OF READING DEVELOPMENT (35% OF THE TEST) 9

Section 0001 Understand Phonological and Phonemic Awareness: 10

Section 0002: Understand Concepts of Print & the Alphabetic Principle: 17

Section 0003: Understand the Role of Phonics in Promoting Reading Development 21

Section 0004: Understand Word Analysis Skills and Strategies 33

DEVELOPMENT OF READING COMPREHENSION (27% OF THE TEST) 37

Section 0005: Understand Vocabulary Development: 38

Section 0006: Understand How to Apply Reading Comprehension Skills and Strategies to

Imaginative/Literary Texts 44

Section 0007: Understand How to Apply Reading Comprehension Skills and Strategies to

Informational/Expository Texts 54

READING ASSESSMENT AND INSTRUCTION (18% OF THE TEST) 58

Section 0008: Understand Formal and Informal Methods for Assessing Reading Development: 59

Section 0009: Understand Multiple Approaches to Reading Instruction 68

TEACHING READING TO ENGLISH LANGUAGE LEARNERS 69

STAGES OF READING DEVELOPMENT 71

INTEGRATION OF KNOWLEDGE AND UNDERSTANDING (20% OF THE TEST) 76

Section 0010: Prepare an organized, developed analysis on a topic related to one or more of the following:

foundations of reading development; development of reading comprehension; reading assessment and

instruction. 77

OPEN RESPONSE QUESTIONS AND MTEL OVERVIEW CHARTS 78

GLOSSARY 92

Overview of the Test

and

Resources for Preparation

Jennifer Arenson Yaeger Foundations of Reading Study Guide 2018

4

Key Websites

➢ Jennifer Yaeger’s Web Site—

o This site includes the MTEL Foundations of Reading Practice Test, MTEL

Foundations of Reading Multiple Choice Analysis, MTEL Test Information Booklet

with sample questions, Put Reading First and many other helpful links:

www.jenniferyaeger.weebly.com

➢ MTEL Website

o The MTEL Foundations of Reading Practice Test:

http://www.mtel.nesinc.com/PDFs/MA_FLD090_PRACTICE_TEST.

pdf

o The MTEL Foundations of Reading MTEL Practice Test Analysis:

http://www.mtel.nesinc.com/PDFs/MA_FLD090_PT_appendix_13.p

df

➢ Put Reading First

http://lincs.ed.gov/publications/pdf/PRFbooklet.pdf

➢ Other Recommended Texts/Study Guides

o Boosalis, Chris Nicholas (2004). Beating them All! Boston: MA. Pearson.

o Kinzer, C.K. & Leu, D.J. (2011) Phonics, Phonemic Awareness, and Word

Analysis for Teachers: An Interactive Tutorial, 9/e. Boston, MA: Allyn and

Bacon.

➢ Reading Rockets

This site includes useful and informative articles on a variety of reading related topics. In

particular, below is a list of web addresses to suggested articles included in this study guide:

Types of Phonics Instruction and Instructional Methods: www.readingrockets.org/article/254

What Does Research Tell Us About Teaching Reading to English Language Learners?:

www.readingrockets.org/article/19757

Jennifer Arenson Yaeger Foundations of Reading Study Guide 2018

5

Test Overview Chart: Foundations of Reading (PreK-6) (90)

Subareas

Approximate

Number of

Multiple-Choice

Items

Number of

Open-Response

Items

I. Foundations of Reading Development

43-45

II. Development of Reading Comprehension

33-35

III. Reading Assessment and Instruction

21-23

IV. Integration of Knowledge and Understanding

2

The Foundations of Reading test is designed to assess the candidate’s knowledge of reading/language

arts required for the Massachusetts Early Childhood, Elementary, and Moderate Disabilities licenses.

This subject matter knowledge is delineated in the Massachusetts Department of Education’s

Regulations for Educator Licensure and Preparation Program Approval (7/2001), 603 CMR 7.06 “Subject

Matter Knowledge Requirements for Teachers.”

The Foundations of Reading test assesses the candidate’s proficiency and depth of understanding of

the subject of reading and writing development based on the requirement that the candidate has

participated in seminars or courses that address the teaching of reading. Candidates are typically

nearing completion of or have completed their undergraduate work when they take the test.

The multiple-choice items on the test cover the subareas as indicated in the chart above. The open-

response items may relate to topics covered in any of the subareas and will typically require breadth

of understanding of the field and the ability to relate concepts from different aspects of the field.

Responses to the open-response items are expected to be appropriate and accurate in the application

of subject matter knowledge, to provide high quality and relevant supporting evidence, and to

demonstrate a soundness of argument and understanding of the field.

Official Massachusetts Tests for Educator Licensure (MTEL) test objectives and preparation materials appear on the MTEL Website at

www.mtel.nesinc.com. Copyright ©2013 Pearson Education, Inc. or its affiliate(s). All rights reserved. Evaluation Systems, Pearson, P.O.

Box 226, Amherst, MA 01004.

Jennifer Arenson Yaeger Foundations of Reading Study Guide 2018

6

Massachusetts Tests for Educator Licensure

TM

FIELD 90: FOUNDATIONS OF READING

TEST OBJECTIVES

Multiple-Choice

Range of

Objectives

Approximate Test

Weight

I. Foundations of Reading Development

01-04

35%

II. Development of Reading Comprehension

05-07

27%

III. Reading Assessment and Instruction

08-09

18%

80%

Open-Response

IV. Integration of Knowledge and Understanding

10

20%

Official Massachusetts Tests for Educator Licensure (MTEL) test objectives and preparation materials appear on the MTEL Website at

www.mtel.nesinc.com. Copyright ©2013 Pearson Education, Inc. or its affiliate(s). All rights reserved. Evaluation Systems, Pearson, P.O.

Box 226, Amherst, MA 01004.

Jennifer Arenson Yaeger Foundations of Reading Study Guide 2018

7

Charts that Support General Concepts on the MTEL

Explicit Instruction

Implicit Instruction

Most important “first step in a sequence of instruction”

For extension and practice; reinforcement of a

previously taught skill

Teacher models, demonstrates; often direct

instruction

Learning may be placed in an authentic context,

where many skills and understandings are

developed simultaneously (e.g. shared reading).

Overt objective; measurable

May feel less clear “what” would be assessed

Principal could walk in the door and without

seeing lesson plan would be able to identify

purpose

Purpose may be unclear to an outside observer

(or even participant)

Focused

May not appear focused

Multiple Choice: How to approach certain types of questions…

When Multiple Choice Questions Relate to

Word Identification

When Multiple Choice Questions Relate to

Vocabulary and Comprehension

Think: “Back to Basics”

Think: Which activity would help develop

independent readers and critical thinkers?

Traditional approach; may feel rote

Focus is on deep, not superficial understanding

Teacher-directed; very focused

Active learning instead of passive

Explicit, systematic, sequential phonics

instruction is of primary importance (use of

syntax, semantics, context clues should be

considered “back-up plans”)

Not “random” assignments, but focused ones

Jennifer Arenson Yaeger Foundations of Reading Study Guide 2018

8

Reading Development and Identification of Gaps

Foundations of Reading

Development

What is often the missing part of the

equation???

Comprehension and

Fluency

Oral Language

Phonological Awareness

(specifically phonemic

awareness)

Emergent Literacy

Concepts about Print

Letter Identification

Alphabetic Principle (letters

and letter combinations

represent sounds)

Word Identification:

• Phonics

• Word Analysis

• Sight Words

• Use of Context

Clues (semantics,

syntax)—often

observed when

students self-correct

Vocabulary

Schema/Background Knowledge

Self-Monitoring

(metacognition--application of active

reading strategies such as questioning,

predicting, connecting)

Demonstrates fluent

reading and

understanding of texts

Jennifer Arenson Yaeger Foundations of Reading Study Guide 2018

9

Foundations of Reading

Development

(35% of the test)

Jennifer Arenson Yaeger Foundations of Reading Study Guide 2018

10

Section 0001 Understand Phonological and Phonemic

Awareness:

✓ The distinction between phonological awareness (i.e. the awareness that oral language is

composed of smaller units, such as spoken words and syllables) and phonemic awareness

(i.e. a specific type of phonological awareness involving the ability to distinguish the separate

phonemes in a spoken word)

✓ The role of phonological awareness and phonemic awareness in reading development

✓ The difference between phonemic awareness and phonics skills

✓ Levels of phonological and phonemic awareness skills (e.g. rhyming, segmenting, blending,

deleting and substituting)

✓ Strategies (e.g., implicit, explicit) to promote phonological and phonemic awareness (e.g.

distinguishing spoken words, syllables, onsets/rimes, phonemes)

✓ The role of phonological processing in the reading development of individual students

(ELLs, struggling readers, highly proficient readers)

Official Massachusetts Tests for Educator Licensure (MTEL) test objectives and preparation materials appear on the MTEL Website at

www.mtel.nesinc.com. Copyright ©2013 Pearson Education, Inc. or its affiliate(s). All rights reserved. Evaluation Systems, Pearson, P.O.

Box 226, Amherst, MA 01004.

Jennifer Arenson Yaeger Foundations of Reading Study Guide 2018

11

Terminology

Phoneme: a phoneme is the smallest part of spoken language that makes a difference in the meaning

of words. English has 41 phonemes. A few words, such as a or oh, have only one phoneme. Most

words, however, have more than one phoneme: The word if has two phonemes (/i/ /f/); check has

three phonemes (/ch/ /e/ /k/), and stop (/s/ /t/ /o/ /p/) has four phonemes. Sometimes one

phoneme is represented by more than one letter.

Grapheme: a grapheme is the smallest part of written language that represents a phoneme in the

spelling of a word. A grapheme may be just one letter, such as b, d, f, p, s; or several letters, such

as ch, sh, th, -ck, ea, -igh.

Phonics: The understanding that there is a predictable relationship between phonemes (sounds of

spoken language) and graphemes (the letters and spellings that represent those sounds in written

language).

Phonemic Awareness: The ability to hear, identify, and manipulate individual sounds – phonemes –

in spoken words. This is purely an auditory skill and does NOT involve a connection to the written

form of language.

Phonological Awareness: A broad term that includes phonemic awareness. In addition to phonemes,

phonological awareness activities can involve work with rhymes, words, syllables, and onsets and

rimes.

Syllable: A word part that contains a vowel, or, in spoken language, a vowel sound.

Onset and Rime: Parts of spoken language that are smaller than syllables but larger than phonemes.

An onset is the initial consonant sound of a syllable; a rime is the part of a syllable that contains the

vowel and all that follows it. STOP (st = onset; op = rime)

Teaching Strategies and Resources for Further Study:

Review Phonemic Awareness Instruction section (pages 1-10) in Put Reading First. You can

read it online or download it from the following address:

www.nifl.gov/partnershipforreading/publications/PFRbooklet.pdf

Jennifer Arenson Yaeger Foundations of Reading Study Guide 2018

12

Comparison of Phonological Awareness and Phonemic

Awareness to Phonics

PHONOLOGICAL AWARENESS

PHONICS

Lights Out!

It’s Auditory

Lights On!

It’s Auditory + Visual

The following examples of phonological awareness

skills are listed in a hierarchy from “basic” to “more

complex”:

1. Rhyming

2. Syllables

3. Counting words in a sentence

4. Hearing/manipulating onset and rime

5. Phonemic Awareness

o The most complex level of phonological

awareness.

o The ability to manipulate and identify the

individual phonemes in spoken words.

o Phonemic awareness skills also fall within a

hierarchy from “basic” to “complex”

o Identification of initial sound (e.g. /v/ is the

first sound in van) is one example of a basic

level.

o Phonemic segmentation is considered a

benchmark for demonstrating a complex level

of phonemic awareness.

o Example: How many sounds/ phonemes in

ship? /sh/ /i/ /p/=3

o One of the greatest predictors of reading

success.

o Alphabetic principle

o Mapping phonemes to their

corresponding letters and letter

combinations (graphemes)

Onset

Rime

st

op

c

at

br

ight

s

ing

sh

ape

l

ip

Jennifer Arenson Yaeger Foundations of Reading Study Guide 2018

13

Elkonin Boxes: Sounds in Words

Jennifer Arenson Yaeger Foundations of Reading Study Guide 2018

14

Phonemic Awareness (Excerpted from

Put Reading First

1

)

:

What does scientifically based research tell us about phonemic awareness

instruction?

Key findings from the scientific research on phonemic awareness instruction provide the

following conclusions of particular interest and value to classroom teachers.

Phonemic awareness can be taught and learned.

Effective phonemic awareness instruction teaches children to notice, think about, and work with

(manipulate) sounds in spoken language. Teachers use many activities to build phonemic awareness,

including:

Phoneme isolation

Children recognize individual sounds in a word.

Teacher: What is the first sound in van?

Children: The first sound in van is /v/.

Phoneme identity

Children recognize the same sounds in different words.

Teacher: What sound is the same in fix, fall, and fun?

Children: The first sound, /f/, is the same.

Phoneme categorization

Children recognize the word in a set of three or four words that has the “odd” sound.

Teacher: What word doesn’t belong? Bus, Bun, Rug.

Children: Rug does not belong. It doesn’t begin with /b/.

Phoneme blending

Children listen to a sequence of separately spoken phonemes, and then combine the phonemes to

form a word. Then they write and read the word.

Teacher: What word is /b/ /i/ /g/?

Children: /b/ /i/ /g/ is big.

*Teacher: Now let’s write the sounds in big: /b/, write b; /i/, write i; /g/, write g.

*Teacher: (Writes big on the board.) now we’re going to read the word big.

Phoneme segmentation

Children break a word into its separate sounds, saying each sound as they tap out or count it.

Then they write and read the word.

Teacher: How many sounds are in grab?

Children: /g/ /r/ /a/ /b/. Four sounds.

*Teacher: Now let’s write the sounds in grab: /g/, write g; /r/, write r; /a/, write

a; /b/, write b.

* Teacher: (Writes grab on the board.) Now we’re going to read the word grab.

* Now it’s “lights on!” What is the skill? ________________________

Jennifer Arenson Yaeger Foundations of Reading Study Guide 2018

15

Phoneme deletion

Children recognize the word that remains when a phoneme is removed from another word.

Teacher: What is smile without the /s/?

Children: Smile without the /s/ is mile.

Phoneme addition

Children make a new word by adding a phoneme to an existing word.

Teacher: What word do you have if you add /s/ to the beginning of park?

Children: Spark.

Phoneme substitution

Children substitute one phoneme for another to make a new word.

Teacher: The word is bug. Change /g/ to /n/. What’s the new word?

Children: bun.

Phonemic awareness instruction helps children learn to read.

Phonemic awareness instruction improves children’s ability to read words. It also improves their

reading comprehension. Phonemic awareness instruction aids reading comprehension. Phonemic

awareness instruction aids reading comprehension primarily through its influence on word reading.

For children to understand what they read, they must be able to read words rapidly and accurately.

Rapid and accurate word reading frees children to focus their attention on the meaning of what they

read. Of course, many other things, including the size of children’s vocabulary and their world

experiences, contribute to reading comprehension.

Phonemic awareness instruction helps children learn to spell.

Teaching phonemic awareness, particularly how to segment words into phonemes, helps children learn

to spell. The explanation for this may be that children who have phonemic awareness understand that

sounds and letters are related in a predictable way. Thus, they are able to relate the sounds to letters

as they spell words.

Some common phonemic awareness terms:

PHONEME MANIPULATION:

When children work with phonemes in words, they are manipulating the phonemes. Types of

phoneme manipulation include blending phonemes to make words, segmenting words into

phonemes, deleting phonemes from words, adding phonemes to words, or substituting one

phoneme for another to make a new word.

BLENDING

When children combine individual phonemes to form words, they are blending the phonemes. They

also are blending when they combine onsets and rimes to make syllables and combine syllables to

make words.

SEGMENTING (SEGMENTATION):

When children break words into their individual phonemes, they are segmenting the words. They are

also segmenting when they break words into syllables and syllables into onsets and rimes.

Jennifer Arenson Yaeger Foundations of Reading Study Guide 2018

16

Phonological, Phonemic Awareness, Phonics Practice

1. Let’s find the pictures that rhyme. That means they have the same ending sound.”

The teacher is developing which skill with the exercise above? _________________

2. “Let’s match pictures that have the same first sound.”

The teacher is developing which skill with the exercise above? _____________

3. Imagine a beginning reader reads the sentence below. Notice how the student segments the

word, then has to blend it back together. This example shows how ________________ supports

decoding.

b-i-g

The dog is big.

4. How many sounds in the word BLAST? __________

Jennifer Arenson Yaeger Foundations of Reading Study Guide 2018

17

Section 0002: Understand Concepts of Print & the

Alphabetic Principle:

✓ Development of the understanding that print carries meaning

✓ Strategies for promoting awareness of the relationship between spoken and written language

✓ The role of environmental print in developing print awareness

✓ Development of book handling skills

✓ Strategies for promoting an understanding of the directionality of print

✓ Techniques for promoting the ability to track print in connected text

✓ Strategies for promoting letter knowledge (e.g., skill in recognizing and naming upper-case

and lower-case letters)

✓ Letter formation (how to form/write letters correctly)

✓ Strategies for promoting an understanding of the alphabetic principle (i.e., the recognition

that phonemes are represented by letters and letter pairs)

✓ Use of reading and writing strategies for teaching letter-sound correspondence

✓ Development of alphabetic knowledge in individual students (English Language Learners,

struggling readers through highly proficient readers)

Terminology

Alphabetic Principle: phonemes (speech sounds) that are represented by letters and letters pairs.

Environmental Print: print found authentically in our environment (stop sign, labels on food).

Emergent Literacy: “There is not a point in a child’s life when literacy begins; rather it is a

continuous process of learning.” This means that we are emerging in our understanding of literacy

before we can even speak. Literacy development begins with one’s earliest experiences of authentic

literacy in the home (from the development of oral language, to having books read to you, to

“scribbling” as a precursor to conventional letter formation). On the MTEL, students described as

“emergent readers” are typically in an early childhood setting or kindergarten. They have not yet

begun formal reading instruction.

Book Handling Skills: Illustrates a child’s knowledge of how books “work” (how to hold the book,

tracking print from left to right, front and back cover, title page, dedication page etc.

Official Massachusetts Tests for Educator Licensure (MTEL) test objectives and preparation materials appear on the MTEL Website at

www.mtel.nesinc.com. Copyright ©2013 Pearson Education, Inc. or its affiliate(s). All rights reserved. Evaluation Systems, Pearson, P.O.

Box 226, Amherst, MA 01004.

Jennifer Arenson Yaeger Foundations of Reading Study Guide 2018

18

Literacy Development in Emergent Readers

• Emergent readers are often identified as preschoolers on the test

• Develop the understanding that print carries meaning (through being read to and through

having their spoken words written in print)

• Mimic readers in their lives (“pretend reading”, emergent storytelling; demonstrating

concepts about print and book handling)

• Mimic writers in their lives (approximating in increasingly conventional ways writing to

convey a message—from squiggles to strings of random letters, to simple phonetic spelling

of dominant sounds in words)

• Build oral language (building receptive and expressive vocabularies through conversation,

through hearing language spoken around them, through being read to)

• Build phonological awareness (e.g. a sense of rhyming)

• Develop knowledge of letter names (letter identification)

• May begin to develop knowledge of alphabetic principle (the sounds associated with letters)

Jennifer Arenson Yaeger Foundations of Reading Study Guide 2018

19

Samples of Emergent Writing

This first example illustrates the

literacy skills of a child who

knows that “print carries

meaning”. She knows that the

squiggles carry meaning and are

different than pictures. She does

not yet know conventional letters.

Learning some letters that hold

relevance for her (i.e. those in her

name or the names of loved ones,

letters from environmental print)

would be a logical next step for

her.

This example shows a child

further along in his literacy

development. He is writing

conventional letters, although the

letters used are random and are

not yet associated with the

corresponding sound(s). He has

grasped the idea that the

function of print is distinct

from that of pictures.

This child is now showing

knowledge of the alphabetic

principle (phonics). She is

labeling the first name of each

person in the picture: Mommy,

Ben, Daddy, Annie. She knows

the letters are represented by

sounds.

Jennifer Arenson Yaeger Foundations of Reading Study Guide 2018

20

“I was going to New Jersey I saw a cool

piece of lightning.”

This child’s phonetic spelling

illustrates her phonics knowledge

(she is applying knowledge of the

alphabetic principle and is

representing sounds with the

letters she knows).

“When I went outside in my back yard I

saw a squirrel chewing on a pinecone.

I was very quiet but then [it ran up a

tree].”

This child’s story shows evidence

of her knowledge of concepts

about print and the alphabetic

principle:

o Left to right and top to

bottom directionality; return

sweep

o Spaces between words

o High Frequency Words: I,

went, in, my, a, on, was, very,

but

o Knowledge of phonics

generalizations with the

dominant consonant and

short vowel sounds

o Developing knowledge of

phonics generalizations for

digraphs and the CVCe (silent

e) pattern. Note how she

“uses but confuses” these

generalizations in the words

“shooing” for “chewing” and

“ven” for “then”. She also

uses the CVCe pattern in the

word “side” but not in

“pinecone”. She is ready to

learn these patterns.

Jennifer Arenson Yaeger Foundations of Reading Study Guide 2018

21

Section 0003: Understand the Role of Phonics in

Promoting Reading Development

✓ Explicit and implicit strategies for teaching phonics

✓ The role of phonics in developing rapid, automatic word recognition

✓ The role of automaticity in developing reading fluency

✓ Interrelationship between decoding, fluency and reading comprehension

✓ The interrelationship between letter-sound correspondence and beginning decoding (e.g.,

blending letter sounds)

✓ Strategies for helping students decode single-syllable words that follow common patterns (e.g.

CVC, CVCC) and multisyllable words

✓ Methods for promoting and assessing the use of phonics generalizations to decode words in

connected text

✓ Use of semantic and syntactic cues to help decode words

✓ The relationship between decoding and encoding (e.g. analyzing the spellings of beginning

readers to assess phonic knowledge, using spelling instruction to reinforce phonics skills)

✓ Strategies for promoting automaticity and fluency (i.e., accuracy, rate, and prosody)

✓ The relationship between oral vocabulary and the process of decoding written words

✓ Specific terminology associated with phonics (e.g. phoneme, morpheme, consonant digraph,

consonant blend)

✓ Development of phonics skills in individual students and fluency in individual students (e.g.,

English Language Learners, struggling readers through highly proficient readers)

Teaching Strategies and Resources for Further Study:

✓ Review Phonics section (pages 11-19) in Put Reading First.

✓ Read article on the Three Cueing Systems in your study guide.

Official Massachusetts Tests for Educator Licensure (MTEL) test objectives and preparation materials appear on the MTEL Website at

www.mtel.nesinc.com. Copyright ©2013 Pearson Education, Inc. or its affiliate(s). All rights reserved. Evaluation Systems, Pearson, P.O.

Box 226, Amherst, MA 01004.

Jennifer Arenson Yaeger Foundations of Reading Study Guide 2018

22

The Three Reading Cueing Systems

2

Capable readers use all three cueing systems. Teachers need to teach and

asssess for all three cueing systems.

Background

Knowledge

Book

Knowledge

Story

Structure

Illustrations

Grammatical

patterns

Natural

language

Book

language

English

syntax

Sight words

Onsets and

rimes

Punctuation

Conventions

of Print

Letter-sound

relations

Jennifer Arenson Yaeger Foundations of Reading Study Guide 2018

23

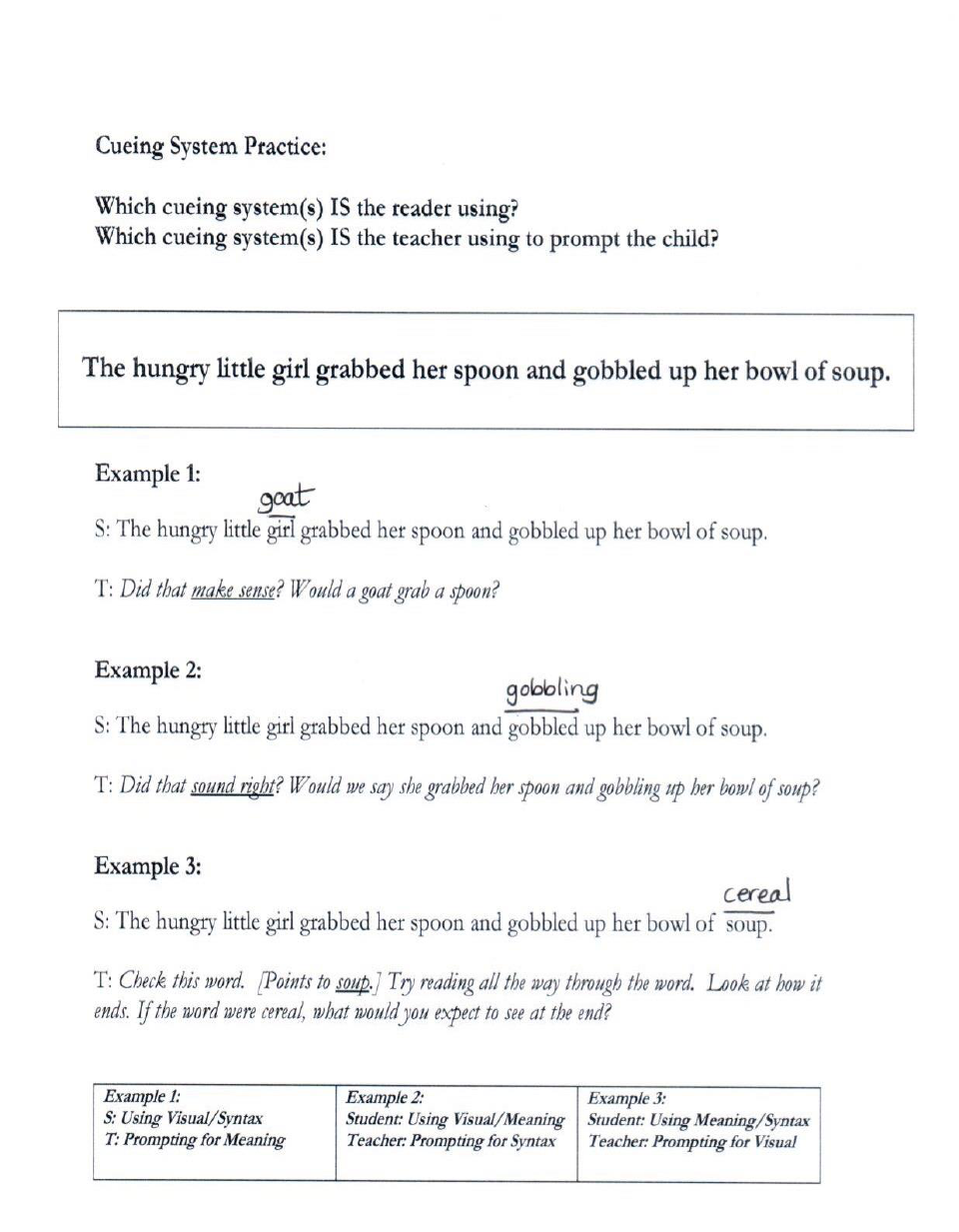

Cueing Systems

What are the cueing systems? Cueing systems are strategies that readers use to predict, confirm and

self-correct when reading words that they do not already know with automaticity.

When analyzing for use of cueing systems, analyze only up to the point of error, not beyond.

A simplified version of the cueing systems:

Cueing System

Questions and

prompts for the

reader:

Demands knowledge

of. . .

MTEL

Interpretation

Meaning/Semantics

(M)

What would

m

ake

sense?

Does that make

sense?

• The context of

sentence,

paragraph,

passage and/or

text

• Background

knowledge

• Illustrations,

where available

Context Clues

-

“Back

-Up Plan”

Structure/Syntax

(S)

What would

s

ound right?

How would we say it?

Would we say it that

way?

• Grammar

• An intuitive sense

of the correct

order of words in

a sentence,

subject-verb

agreement,

consistent use of

tense

Visual/Phonics

(V)

What word matches the

print?

What sounds do the

letters/letter

combinations make?

“Sound it out”.

“Tap it out.”

“Chunk it.”

• Alphabetic

principle

• Letter-sound

correspondence

• Phonics

generalizations

• Structural Analysis

Strategies

THE CUEING

SYSTEM GIVEN

GREATEST

PRIORITY AND

IMPORTANCE for

INSTRUCTION—

Jennifer Arenson Yaeger Foundations of Reading Study Guide 2018

24

Jennifer Arenson Yaeger Foundations of Reading Study Guide 2018

25

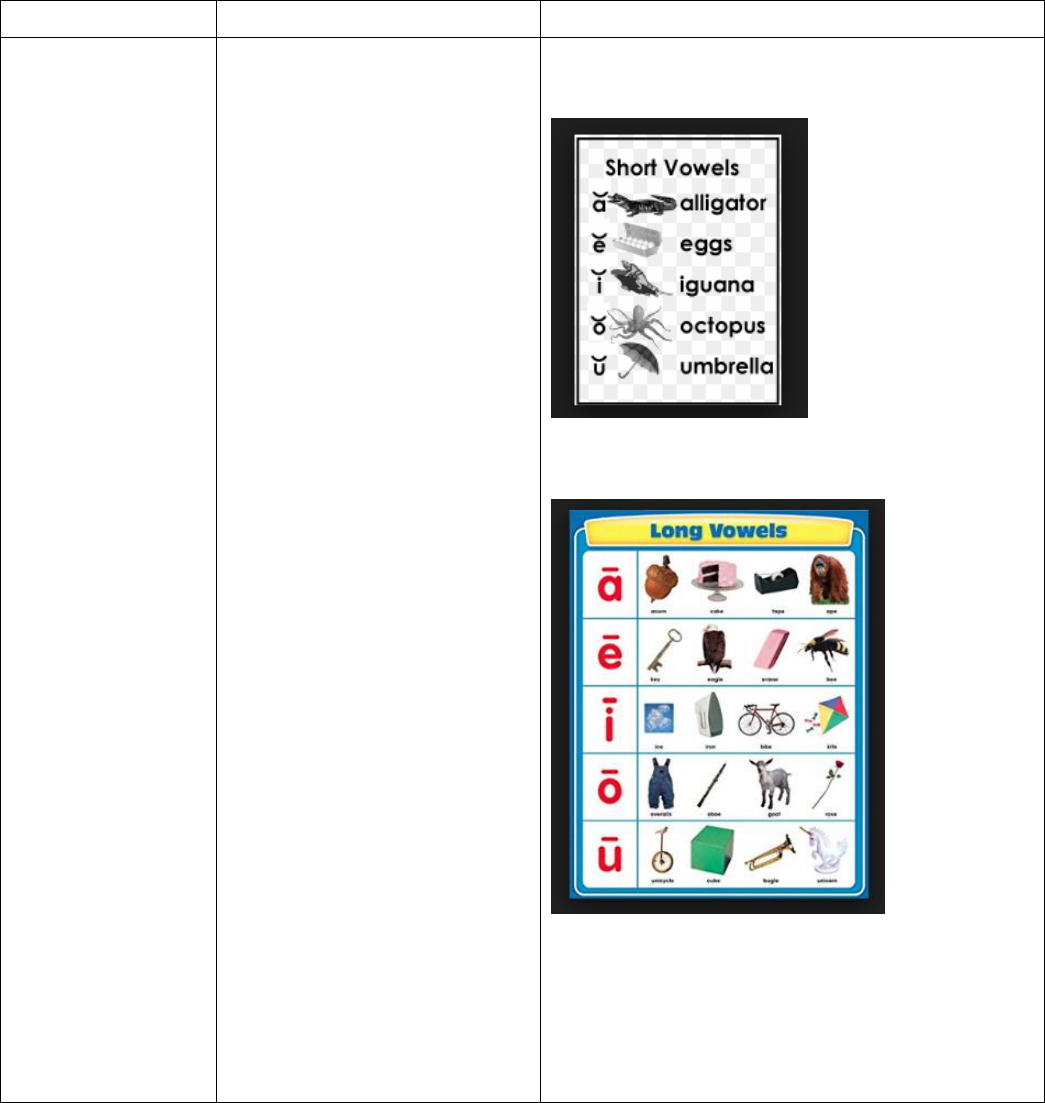

Important Phonics Generalizations and Terms

3

,

4

Consonants (C)

Vowels (V)

Some useful

generalizations

about

consonants and

vowels:

B, C, D, F, G, H, J, K, L, M, N,

P etc.

Consonant letters are fairly

reliable. There is a strong

relationship between the letter

and the sound we expect it to

represent.

Consonants represent the

dominant sounds in words.

Generally, vowel sounds are considered short, such

as in the sounds below:

Or long, such as the sounds in the words below:

Vowels are more difficult to learn because each

letter is represented by more than one distinct

sound; the sound depends on the other letters

around it. Vowel sounds are also harder to

discriminate (hear, manipulate, identify).

Jennifer Arenson Yaeger Foundations of Reading Study Guide 2018

26

CONSONANTS

VOWELS

. . .but there are

irregularities. . .

A letter may represent more than one

phoneme. For example, some

consonant letters may produce a hard or

soft soft.

The hard c is the sound of /k/ in cat.

The soft c is the sound of /s/ in cent,

and city.

The hard g is the sound of /g/ in game.

The soft g is the sound of /j/ in gem and

gentle.

Vowel sounds behave differently in

accented and unaccented syllables.

The vowel is most clearly heard in

the accented syllable.

Final -y

Y functions as a vowel in the final

position (e.g. very, merry)

BLend DigraPH

(Each phoneme still heard) (Combination of letters creates a new phoneme)

Blends

bl, sm, scr, gr, sl, etc.

Blends are consonant pairs or clusters.

Trick to help you remember: The bl in blend

is an example…notice that you still hear

each sound “through to the end” (these

letters do NOT make a new sound when

combined).

(The term “blend” is generally used

when referring to consonants. A

dipthong, described below, is the

vowel equivalent.)

Digraphs

ch, ph, sh, th, wh, tch,

gh (final position only),

ng (final position only)

etc.

Two consonant letters that together

make a new sound.

Trick to help you remember:

A digraph makes me laugh. The last

two letters in digraph (ph) and in laugh

(gh) are connected to form two

completely new sounds.

ai, ay, oa, ee, ea

Generalization: “When two vowels

go walking, the first one does the

talking and says its name”.

These combinations of vowels

together make one new sound.

Jennifer Arenson Yaeger Foundations of Reading Study Guide 2018

27

CONSONANTS

VOWELS

Silent “E”

When a short word ends with an “e”,

the first vowel usually has the long

sound and the final “e” is silent.

Word or syllable patterns that follow

this generalization:

VCe (ape)

CVCe (cape)

CCVCe (brave)

“R-Controlled

Vowels” or

“Vowels followed by

r

”

When a vowel letter is followed by

“r”, the vowel sound is neither long

nor short (it is different!).

Examples: “ar” in car, “or” in for, “ir”

in bird

Diphthongs

A blend of vowel sounds, where

each sound is still heard.

The two most agreed upon vowel

combinations are “oi” in boil and

“ou” in mouth or ouch. The words

“toy” and “cow” are also considered

to contain diphthongs (ow and oy).

Jennifer Arenson Yaeger Foundations of Reading Study Guide 2018

28

Approaches to Phonics Instruction

Synthetic vs. Analytic Approaches to Phonics Instruction:

Synthetic Phonics:

• a part-to-whole phonics approach to reading instruction in which the student learns the sounds

represented by letters and letter combinations, blends these sounds to pronounce words, and

finally identifies which phonic generalizations apply. . .

5

Example: Teaching

ai

vowel digraph using a synthetic approach

o Students are introduced to a new phonics pattern (the vowel digraph ai) through

explicit and direct instruction followed by blending individual letters and letter

combinations into a new word.

Analytic Phonics:

• a whole-to-part approach to word study in which the student is first taught a number of sight

words and then relevant phonic generalizations, which are subsequently applied to other words;

deductive phonics. See also whole-word phonics.

6

Example: Teaching

ai

vowel digraph using an analytic approach

o Students are introduced to a new phonics pattern by comparing the whole words ran

and rain and are prompted to notice the change in the vowel pattern and in the

pronunciation of the two words.

What do you notice?

Jennifer Arenson Yaeger Foundations of Reading Study Guide 2018

29

Researched-Based Sequence of Instruction for Phonics

7

(According to Chall)

Early/Beginning Readers

Phonics instruction begins with words containing short vowel sounds. These words

begin with single consonant letters and then include consonant blends (e.g. cast) and

digraphs (e.g. chat). Beginning readers (typically in late kindergarten through grade 1)

learn consistent phonics generalizations. In other words, they learn to read words that

follow predictable patterns.

CVC CVCC CCVC CCVCC

cat cast trip stick

sip tent twig truck

bug lift ship twist

map fist chat blend

The words listed above are also known as closed syllables. They end in a consonant

and contain a short vowel sound.

Next, children are introduced to LONG VOWEL PATTERNS.

CVCe: The “Silent e” Pattern

same

late

bike

CVVC: Words with Vowel Digraphs

rain

team

bait

train

chain

toast

reach

speech

Jennifer Arenson Yaeger Foundations of Reading Study Guide 2018

30

SIGHT WORDS

Children at this stage also begin to learn a bank of sight words. Usually the term

“sight words” are used interchangeably with “high frequency words”. These are words

that appear so often in the texts children read (and write!) that it is more efficient to

memorize these words and know them with automaticity. Many of these words are

also irregular (they cannot be decoded following phonics generalizations).

Examples of sight words for beginning readers:

I, me, you, mom, play, the

Examples of sight words for more proficient readers:

because, friend, there, when, could, should, always

Note: The word “sight words” can also refer to any word an individual child knows

automatically by sight. A child’s “sight word vocabulary” refers to the bank of words

an individual knows with automaticity.

Transitional Readers (typically 2

nd

grade and up)

Students at this level begin to see lots of words that are not necessarily in their oral

vocabulary. The patterns may be consistent, but the features become more complex

and many words are now multi-syllable. The derivation of these words may indicate

their meaning, pronunciation, and spelling.

spoil

place

bright

shopping

carries

chewed

shower

bottle

favor

ripen

cellar

fortunate

pleasure

Jennifer Arenson Yaeger Foundations of Reading Study Guide 2018

31

Fluency

Reading fluently includes three elements (accuracy, rate and prosody).

Accuracy: The percentage of words read correctly (usually allowing for self-

corrections).

Rate: The speed with which a text is read (Words Per Minute: WPM)

Prosody: The overall “smoothness” of the reading which includes phrasing,

expression and intonation.

Phrasing: I picked up my son and we drove to the soccer field.

Expression: “Wait for me!” exclaimed the child.

Intonation: Is that for me?

To build oral reading fluency, children need massive amounts of practice reading

independent level texts. Independent texts are those with which the student reads

with 95% or greater accuracy and with satisfactory comprehension. With independent

level texts, the reader reads with no more than 5/100 errors (95/100 correct). When

identifying the level of text difficulty appropriate for different purposes, keep in mind

the accuracy rates below:

Independent Level

Instructional Level

Frustration Level

95-100% accuracy

This is the level at which

students should practice

reading independently to

build oral reading fluency.

90-94% accuracy

This is the student’s zone of

proximal development where

small group instruction

(such as guided reading)

or individual instruction is

appropriate.

Below 90% accuracy

There is little evidence to

show that reading

development can occur at

this level of difficulty.

See note below about the place

for reading complex texts at

one’s grade level, even if the

text level is at the reader’s

“frustration level.”*

Jennifer Arenson Yaeger Foundations of Reading Study Guide 2018

32

What strategies support oral reading fluency?

• Repeated readings of familiar texts

• Echo reading

• Choral reading

• Reader’s theater

Why is fluency so important?

• With greater fluency students can focus their cognitive resources on the

meaning of the text; they cannot focus on the meaning if they are have a slow

rate (word-by-word reading). They cannot focus on the meaning if they are

struggling to identify the words on the page.

The place for reading complex texts even if they are at a “Frustration Level”:

To develop proficient readers (readers who read fluently and comprehend deeply),

readers need instruction that is differentiated. Reading instruction will be most

effective when readers are instructed individually and in small groups with texts that

have a slight degree of difficulty (these are the instructional level texts identified in the

chart above).

That said, all children (regardless of their identified reading levels) should have access

to complex texts—texts with the language, vocabulary, concepts and content

identified as appropriate for the grade level. The teacher’s read-aloud provides such

access as does close reading, a method by which the teacher engages children in

repeated readings of short sections of text, providing modeling and scaffolding with

each successive reading.

This emphasis on reading complex texts is a foundation of the Common Core State

Standards (see the Introduction):

The Reading standards place equal emphasis on the sophistication of what

students read and the skill with which they read. Standard 10 defines a grade-

by-grade “staircase” of increasing text complexity that rises from beginning

reading to the college and career readiness level. Whatever they are reading,

students must also show a steadily growing ability to discern more from and

make fuller use of text, including making an increasing number of connections

among ideas and between texts, considering a wider range of textual evidence,

and becoming more sensitive to inconsistencies, ambiguities, and poor

reasoning in texts.

Jennifer Arenson Yaeger Foundations of Reading Study Guide 2018

33

Section 0004: Understand Word Analysis Skills and

Strategies

✓ The development of word analysis skills and strategies in addition to phonics, including

structural analysis

✓ Interrelationships between word analysis skills, fluency, and reading comprehension

✓ Identification of common morphemes (e.g., base words, roots, inflections and other affixes)

✓ Recognition of common prefixes (e.g. un-, re-, pre-), and suffixes (-tion, -able) and their

meanings

✓ Knowledge of Latin and Greek roots that form English words

✓ Use of syllabication as a word identification strategy

✓ Analysis of syllables and morphemes in relation to spelling patterns

✓ Techniques for identifying compound words

✓ Identification of homographs (i.e., words that are spelled the same but have different

meanings and may be pronounced differently [e.g.. bow, part of a ship/bow, to bend from

the waist; tear, a drop of water from the eye/tear, to rip])

✓ Use of context clues (e.g., semantic, syntactic) to help identify words and to verify

pronunciation and meaning of words

✓ Development of word analysis and fluency in individual students (e.g., English Language

Learners, struggling readers through highly proficient readers).

Terminology

Morpheme: any unit in a word is a morpheme (in the word dogs, “dog” and the “s,” are both

morphemes)

Base Word: A base-word is usually a simple word from which you can build a family of words

around it. If you start with “place” you can say places, placing, placings, replace, placement, etc.

Root Word: Root word refers to the origin of a word. For example, “locus” means place in

Latin. From this root word derives words such as local, locate, locality, relocation and phrases

like “in loco parentis.”

Prefix: Morpheme added to the beginning of the word

Suffix: Morpheme added to the end of the word

Affix: Prefixes, suffixes and inflectional endings

Also see homograph, homonym and homophone in the Glossary section

Official Massachusetts Tests for Educator Licensure (MTEL) test objectives and preparation materials appear on the MTEL Website at

www.mtel.nesinc.com. Copyright © 2013 Pearson Education, Inc. or its affiliate(s). All rights reserved. Evaluation Systems, Pearson, P.O.

Box 226, Amherst, MA 01004.

Jennifer Arenson Yaeger Foundations of Reading Study Guide 2018

34

Analysis of Word Structure: When Decoding Isn’t Enough

When reading multisyllabic words, readers may use phonics generalizations to decode--“sound out”-

- individual syllables or parts of a longer word; however, decoding phoneme-by-phoneme is simply not enough.

When encountering multisyllabic words, readers now need to draw on a host of additional strategies

to identify unfamiliar words and they need to be able to break apart these unfamiliar words

efficiently and strategically. For example, they need to identify smaller words within larger words,

notice roots and bases, prefixes and suffixes and so on. They may also break apart words by syllable.

Not only do these skills help the reader identify the word on the page, structural analysis strategies

help the reader understand the meaning of the word itself by breaking apart words into “meaning-

bearing parts”.

PEDOMETER

BIOLOGY

MISFORTUNE

Some examples of generalizations taught with multisyllabic words:

Closed Syllables

When a short word (or syllable) with one vowel letter ends in a

consonant, the vowel sound is usually short. Word patterns that follow

this rule are:

VC (am) CVCC (damp)

CVC (ham) CCVC (stem)

Open Syllables

When a word or a syllable has only one vowel and it comes at the end of

the word or syllable, it usually creates the long vowel sound.

CV (he, me) CV-CVC (ti-ger, na-tion, hu-man)

Inflectional Endings

Affixes added to the end of words to indicate number (ox/oxen,

bush/bushes) or tense (playing, played, plays)

Syllabication

Examples:

sum-mer pre-vent um-brel-la

Compound Words

Examples:

pancake shoelace

Contractions

Examples:

have not: haven’t can not: can’t

Prefixes/Suffixes

Examples:

re- un- -able -tion

Schwa

An unstressed vowel sound, such as the first sound in “around”

and the last vowel sound in “custom”. In the examples below, the bold

part of the word is the accented (stressed) syllable.

Would you present the present to the guest of honor?

It is a good idea to record your expenses so you have a record of them.

8

Jennifer Arenson Yaeger Foundations of Reading Study Guide 2018

35

Key Principles of Structural Analysis:

Reading, Spelling and

Pronouncing Multisyllabic Words

9

1) When spelling unfamiliar multisyllabic words the speller needs to keep in mind that

relying on sounds of the word parts for spelling is no longer as reliable as it was with

single syllables.

Example: Consider the words dollar, faster, actor. The ending sound is the same, but the

spelling is different.

What should you emphasize?

Help children learn that while they do not know the spelling of

the whole word, they likely know a part of the word. Slow down on the less familiar part (in this

case, the unaccented syllable).

2) Students need to pay close attention when joining syllables (syllable juncture). One key

principle: to mark the short vowel, double the consonant.

Example: Tigger vs. tiger; gripped vs. griped; hu-man; mam-mal.

What should you emphasize?

Pay attention to the vowel sound of the first syllable. Determining whether it is a long or short

vowel sound will help you decide on the spelling.

3) Accent and stress play a key role in spelling multisyllabic words. There are no fixed

rules that govern the spelling of these words, but there are some common

generalizations…

Example: Verbs and adjectives tend to end in –en (waken, golden) whereas nouns tend to end in –on

(prison, dragon). Comparative adjectives tend to end in -er (smaller, taller).

Some spellings are simply more common than others:

Example there are over 1,000 words ending in –le, but only 200 that end in –el.

What should you emphasize?

Help students notice the most common patterns and

generalizations through sorts and discussions.

4) Words that are related in meaning are often related in spelling, despite changes in

sound.

Example: Consider the following spelling: COMPISITION. The

o

in the word

compose

is the clue

to its spelling.

Similarly, DECESION is spelled with an

i

instead of an e because it comes from the word decide.

What should you emphasize?

By thinking of a word that is related to one you’re trying to spell,

you will often discover a helpful clue.

Jennifer Arenson Yaeger Foundations of Reading Study Guide 2018

36

5) Polysyllabic (multisyllabic) words often have unstressed syllables in which the vowel is

reduced to the schwa sound, but this sound can be written in several different ways.

What should you emphasize?

Remembering the root word will often help the speller choose

the correct spelling.

6) The suffix pronounced /shun/ can be spelled several ways and can cause the

consonant or vowel sound to alternate, changing the pronunciation.

Example: Note the different spellings in protection, invasion, admission, and musician.

Also note how the suffix can affect the base word and pronunciation in these interesting

ways: detect/detection (the /t/ sound becomes a /sh/ sound); and decide/decision

(where the /i/ sound moves from long to short).

What should you emphasize?

There are MANY familiar words to examine. By noticing the

patterns in these familiar words, students will begin to see the generalizations that emerge. These

generalizations are also included in the chart below, but it is recommended that students spend

lots of time examining these patterns before sharing generalizations with them.

Suffix Generalizations:

1. Base words that end in –ct or –ss just add –ion (traction, expression)

2. Base words that end in –ic add –ian (magician)

3. Base words that end in –te drop the e and add –ion (translation)

4. Base words that end in –ce drop the e and add a –tion (reduce/reduction)

5. Base words that end in –de and –it drop those letters and add –sion or –ssion

(decide/decision, admit/admission).

6. Sometimes –ation is added to the base word, which causes little trouble for spellers

because it can be heard (transport, transportation)

A PROCESS FOR ANALYZING WORDS

Notice the Spelling (the patterns of letters):

1) Look at the roots/bases. Is there a pattern in how they are spelled? For example, do they

end with a vowel? One consonant? A consonant blend or digraph?

2) Look at the prefix/suffix. Is there a pattern in how they are spelled? Does the spelling

change depending on the root or base?

Notice the Pronunciation (the sound)

1) Does the pronunciation change when the spelling changes?

2) Does the pronunciation stay the same even if the spelling change? (In other words, is the

pronunciation reliable?)

Jennifer Arenson Yaeger Foundations of Reading Study Guide 2018

37

Development of Reading

Comprehension

(27% of the test)

Jennifer Arenson Yaeger Foundations of Reading Study Guide 2018

38

Section 0005: Understand Vocabulary Development:

✓ The relationship between oral and written vocabulary development and reading

comprehension.

✓ The role of systematic, non-contextual vocabulary strategies (e.g., grouping words based on

conceptual categories and associative meanings) and contextual vocabulary strategies (e.g.

paraphrasing)

✓ The relationship between oral vocabulary and the process of identifying and understanding

written words

✓ Strategies for promoting oral language development and listening comprehension (e.g.,

read-alouds, word explanation strategies)

✓ Knowledge of common sayings, proverbs and idioms (e.g. It’s raining cats and dogs; Better safe

than sorry.)

✓ Knowledge of foreign words and abbreviations commonly used in English (e.g. RSVP)

✓ Criteria for selecting vocabulary words

✓ Strategies for clarifying and extending a reader’s understanding of unfamiliar words

encountered in connected text (e.g. use of semantic and syntactic cues, use of word maps,

use of dictionary)

✓ Strategies for promoting comprehension across the curriculum by expanding knowledge of

academic language, including conventions of standard English grammar and usage,

differences between the conventions of spoken and written standard English, general

academic vocabulary and content-area vocabulary (e.g., focus on key words)

✓ The importance of frequent, extensive, varied reading experiences in the development of

academic language and vocabulary

✓ Development of academic language and vocabulary knowledge and skills in individual

students (e.g., English Language Learners, struggling readers through highly proficient

readers).

Official Massachusetts Tests for Educator Licensure (MTEL) test objectives and preparation materials appear on the

MTEL Website at www.mtel.nesinc.com. Copyright © 2013 Pearson Education, Inc. or its affiliate(s). All rights

reserved. Evaluation Systems, Pearson, P.O. Box 226, Amherst, MA 01004.

Jennifer Arenson Yaeger Foundations of Reading Study Guide 2018

39

Terminology:

Oral Vocabulary: The vocabulary one can use appropriately in speech and can understand when

heard aloud

Written Vocabulary: The words one can understand when seen in written form.

Semantic Mapping: A strategy that visually displays the relationship among words and helps to

categorize them.

Teaching Strategies:

Review Vocabulary section (pages 33-45) in Put Reading First.

Jennifer Arenson Yaeger Foundations of Reading Study Guide 2018

40

Vocabulary Development: Overview

Vocabulary relates to understanding the MEANINGS of words.

Why is vocabulary so important to reading development?

• Teaching vocabulary improves students’ comprehension.

• Students’ ability to infer the meaning of the text is strongly related to their understanding of

the meanings of words.

• The ability to read complex texts depends on a strong vocabulary.

Do we have a vocabulary “problem”?

• Students need but lack deep and meaningful understanding of words.

o There are three levels of word knowledge: unknown, acquainted, and established

10

o Words at the established level are words that are easily, rapidly and automatically

understand.

o It is critical that we build students’ established knowledge of words

• The more children are read to from birth, the more words in their oral and listening

vocabularies.

• Reading aloud is also key for reading development. Many of the words in books do not arise

naturally in discussions; wide reading builds rich vocabulary knowledge.

• A child’s background knowledge also strongly affects their exposure to vocabulary. For

example, consider children who lack knowledge of city life who live in rural settings and vice

versa. Children are exposed to different words depending on their life experiences.

• Many children can appear to be strong readers because they read grade level texts with a high

degree of accuracy; however, many of these same children may have little understanding of

what they read.

o When accuracy is strong and comprehension is weak, start by assessing whether or

not the student understands the meanings of words in context. Lack of vocabulary

knowledge is often the missing factor.

Strategies for Teaching Vocabulary Effectively

Effective instruction in vocabulary involves teaching both selected words and strategies for determining the meaning

of unfamiliar words.

• Provide explicit instruction in selected words that will likely be seen in other contexts

o Semantic maps and webs are effective for helping children make connections

between known words and new words; graphic organizers provide a visual image of

these connections and help children retain the meanings (see example on the next

page)

o Child-friendly definitions help children understand words in a meaningful context.

For example, consider the dictionary definitions for pedantic:

▪ Random House, Webster’s Dictionary: overly concerned with minute details or

formalisms, esp. in teaching

▪ Child-Friendly Definition: being overly concerned with sticking to unimportant

rules, being “stuffy” and inflexible about the small details of things

o Providing opportunities to discover synonyms and antonyms help to clarify and

expand word knowledge

Jennifer Arenson Yaeger Foundations of Reading Study Guide 2018

41

▪ Collins Thesaurus of English Language—Synonyms for “pedantic”: hairsplitting,

particular, formal, precise, fussy, picky (informal); punctilious, priggish,

pedagogic, pompous, erudite, didactic, bookish (formal)

o Providing examples of words that “fit” and “don’t fit” (i.e. providing examples and

“non-examples”) also help students retain definitions

o Providing multiple exposures of these words also help students retain word

meanings

Semantic Map (example)

Jennifer Arenson Yaeger Foundations of Reading Study Guide 2018

42

• Provide explicit instruction in strategies to determine the meaning of unfamiliar words

o Use of context clues

o Analysis of word parts (morphemic analysis) such as prefixes, suffixes, roots and

bases

o Dictionary skills

• Provide explicit instruction of technical (“domain specific”) vocabulary important to

understanding content in social studies and science (e.g. lava, proton, atmosphere, colony)

• Provide opportunities for children to hear books read aloud.

o Choose books that are ABOVE the students’ own reading level. Point out the

meanings of important and a few selected words in context.

• Provide opportunities for children to read independently; wide reading across genres exposes

students to words that do not appear in oral conversation.

o A great deal of vocabulary can be learned from just reading. Even “children who

read just ten minutes a day outside of school experience substantially higher rates

of vocabulary growth between second and fifth grade than children who do little

reading.”

11

• Provide opportunities for children to talk about what they read and what is read to them;

talk supports vocabulary development and comprehension.

• Provide opportunities for children to make a connection between known words in speaking

and the less familiar written form.

o An effective strategy is to make sure children see the word at the same time that it is

pronounced.

• Ensure that vocabulary instruction is active and engaging; engage children in developing

word consciousness.

• Pair reading and writing (each supports the other!)

Note: The above strategies are suggested in place of traditional approaches that emphasize rote memorization of

abstract definitions. For example, looking up and writing definitions from the dictionary for a long list of vocabulary

words is not shown to be an effective practice for building vocabulary. Writing new vocabulary words in a sentence, in

most cases, is also not an effective practice.

Some Important Considerations for Beginning Readers:

• Beginning reading instruction should focus on helping children learn to read words already

in their spoken vocabularies

• As children develop as readers they should be taught vocabulary words that are unknown

(but the concept is known), such as “pant” (a dog pants). This is especially important for ELLs

because they have many concepts, but not the words.

• Teach new words that represent new concepts. This is perhaps the most demanding.

When answering multiple choice questions related to vocabulary, consider the purpose:

o Is it to prepare students for content area (e.g. science, history) instruction? If so, teach the

concept words that are unfamiliar and necessary to understand the topic.

o If the question is asking about preparing students to understand literary texts, consider the

words that would be helpful to know in this text, but also in others (words that would

provide more “bang for the buck”). These words are also known as Tier II words (Beck).

Jennifer Arenson Yaeger Foundations of Reading Study Guide 2018

43

Vocabulary Tiers

By: Isabel Beck

12

The siblings waited anxiously for the news from the

surgeon. When she walked through the doors into the

corridor, they took one look at her face and began to bawl

with elation.

Note how knowledge of Tier II vocabulary words affects one’s

overall comprehension of the passage.

Tier 3

Domain-Specific

Science/History

e.g. volcano, atmosphere

Tier 2

More sophisticated synonyms for words many children

will know

e.g. generous, bawl, whine, infant

Tier 1

Require no instruction; concepts already familiar;

words familiar

e.g. kind, cry, baby

Jennifer Arenson Yaeger Foundations of Reading Study Guide 2018

44

Section 0006: Understand How to Apply Reading

Comprehension Skills and Strategies to

Imaginative/Literary Texts

✓ Knowledge of reading as a process to construct meaning

✓ Knowledge of reading comprehension and analysis skills for reading literature (e.g., analyzing

a text’s key ideas and details, interpreting an author’s use of craft and structure, integrating

knowledge and ideas from multiple literary works)

✓ Knowledge of levels of reading comprehension (i.e., literal, inferential and evaluative) and

strategies for promoting comprehension of imaginative/literary texts at all three levels

✓ Strategies for promoting close reading of imaginative/literary texts

✓ Development of literary response skills (e.g. connecting elements in a text to prior

knowledge and other sources; using evidence from a text to support analyses, develop

summaries, and draw inferences and conclusions)

✓ Development of literary analysis skills (e.g. identifying features of different literary genres,

analyzing story elements, analyzing character development, interpreting figurative language,

identifying literary allusions, analyzing the author’s point of view)

✓ Use of comprehension strategies to support effective reading (e.g., rereading, visualizing,

reviewing, self-monitoring and other metacognitive strategies)

✓ Use of oral language activities to promote comprehension (e.g. retelling, discussion)

✓ The role of reading fluency in facilitating comprehension

✓ Use of writing activities to promote literary response and analysis (e.g., creating story maps

and other relevant graphic organizers; comparing and contrasting different versions of a

story, different books by the same author, or the treatment of similar themes and topics in

different texts or genres)

✓ Development of reading comprehension skills and strategies for individual students (e.g.,

English Language Learners, struggling readers through highly proficient readers)

Official Massachusetts Tests for Educator Licensure (MTEL) test objectives and preparation materials appear on the MTEL Website at

www.mtel.nesinc.com. Copyright © 2013 Pearson Education, Inc. or its affiliate(s). All rights reserved. Evaluation Systems, Pearson, P.O.

Box 226, Amherst, MA 01004.

Jennifer Arenson Yaeger Foundations of Reading Study Guide 2018

45

Terminology:

Literal, Inferential and Evaluative Questions (see page that follows)

Metacognitive Strategies: These are strategies that help the reader become more aware of their own

reading process, their thoughts as they read, and help the reader to have more control over their

reading (e.g. noticing when comprehension breaks down and using “fix-up” strategies, such as

rereading or paraphrasing, to comprehend).

Graphic Organizers: Visual “maps” or diagrams that help the reader organize the information they

read. A story map is one type of graphic organizer. It allows the reader to organize the elements of a

story (characters, setting, events, problem, solution).

Teaching Strategies:

Review Comprehension Section in Put Reading First.

Jennifer Arenson Yaeger Foundations of Reading Study Guide 2018

46

Best Practices in Comprehension Instruction

Reading = Thinking

Reading=Actively engaging in making meaning from texts

o Comprehension is not just “caught” (assessed); it is taught. One of the most effective

methods for teaching students how to comprehend is by demonstrating one’s own thinking

through a “think aloud”. Through this method the teacher talks out loud about his/her

thinking as she engages with a portion of a text, demonstrating her strategies and ideas while

making meaning.

o Traditional post-reading activities (e.g. answering a series of questions at the end of chapter

or book or even completing creative projects such as dioramas) are not considered effective

ways to strengthen students’ comprehension skills.

o Instead, conversation is at the heart of effective comprehension instruction. Teachers

engage children in whole class, small group and one-on-one conversations about texts.

Written response to reading occurs as students move into upper elementary grades, but these

written responses have a more authentic feel (see examples below). With both conversation

and written responses, students are expected to support their ideas with text evidence.

▪ Primary grade children (K-2) learn how to comprehend and demonstrate

comprehension, mostly through conversation among peers. A teacher may

engage children in an interactive read-aloud in which children are prompted

to talk with partners during key parts in the text. These ideas are then shared

as a class. Conversation about texts is also an important part of guided

reading.

▪ Upper grade children (3-6) also develop comprehension through conversation

among peers. During these grades, the teacher will likely still read aloud and

engage students in whole-class conversations, but students also engage in

comprehension conversations in increasingly independent ways (in the form

of book clubs, literature circles). They also begin to demonstrate their

comprehension through writing, sometimes by jotting their thinking on post-

it notes or by developing written response to ideas in reader response

journals and reader’s notebooks.

Example of Think-Aloud: Blackout

As children progress through the grades, they engage with texts in increasingly sophisticated ways,

but the goals for each grade are essentially the same.

Jennifer Arenson Yaeger Foundations of Reading Study Guide 2018

47

Literary Response Skills:

Examples: Retelling and Summarizing

Readers should be able to retell (and eventually summarize) the key ideas and details from a story

that has been read aloud to them or that they have read independently. Retelling/summarizing these

key elements is the same as demonstrating knowledge of story grammar (the elements of stories).

Primary grade children (K-2) may:

o Create a story map with their teacher and peers that identifies the key story elements (setting,

characters, key events, problem, solution)

o Put items representing a story into a sequence (e.g. straw, hay, bricks for The Three Little

Pigs)

o Discuss key events as part of a whole class post-reading conversation

o Create a simple summary through interactive or shared writing (in which the teacher leads

the class in creating an enlarged class-created summary)

Upper grade children (3-6) may:

o Discuss the key story elements as part of a whole class conversation

o Summarize a text in a one-on-one conference

o Write a summary in a response journal

Examples of Literary Analysis:

Primary Grades: analyzing character feelings, character traits, lesson/moral and supporting one’s

analysis with text evidence

Upper Elementary: analyzing character traits, character change, character motivation, cause/effect

of events, problem and resolution, central message/themes and supporting one’s analysis with text

evidence

o Plot vs. Theme

o Plot: What happened (key events)

o Theme: What the book is about (the “big ideas”) …for example, what is the author

saying about Friendship? Love? Courage? Growing Up?

Jennifer Arenson Yaeger Foundations of Reading Study Guide 2018

48

Craft and Structure: Analysis of the text as an “object”—how it’s structured (e.g. chronological,

use of flashbacks); who is telling the story (who is the narrator? whose point of view?) and the

impact of that perspective on the story; the writing techniques (writing style) the author employs

(e.g. how the author might slow down the action to build suspense or use dialogue for humor); how

the author might use particular words or phrases to convey mood/tone/develop a theme; use of

literary devices (figurative language, symbolism)

Close Reading: While there are many interpretations of close reading, the one espoused by the

Foundations of Reading test focuses on a sequence of repeated readings of an excerpt from a text

or short “chunk” of text. Through each successive reading, students are guided to focus on a

different aspect of the reading (such as the meaning of selected words and phrases) in order to form

a deeper interpretation of the text. This process is used to support children in reading complex texts

at grade level.

Development of literary response skills and Development of literary analysis skills

https://study.com/academy/lesson/literary-response-analysis-skills-types-examples.html

Jennifer Arenson Yaeger Foundations of Reading Study Guide 2018

49

Levels of Comprehension

Levels (from the

more basic to the

more complex)

Definition

Examples

Literal

--Often

determined

through a retelling

in which the

student can repeat

back the sequence

of events and

identify key story

elements (e.g. who,

what, when,

where)

Information that is stated

explicitly in the text such as

who, what, when, where,

why.

You can find the

information “right there” on

the page…just read the lines.

Excerpt from Text:

It was a bright, sunny day in April, and the flowers

were in bloom.

When does the story take place? A sunny

day in April.

What was in bloom?

Flowers.

Inferential

Information that is implied

within the text, but not

directly or explicitly stated.

The reader needs to “search

and find” clues within the

text and then read between the

lines.

Excerpt from Text:

Annie burst out of the house in her bare feet. She

took a deep breath, filling her lungs with the warm

air and let her toes discover the fresh grass for the

first time in months.

When do you think the story takes

place? Provide evidence. The story

probably takes place in the beginning of

spring. The fact that Annie burst out of the

house may indicate that she was excited by

the change in season. The text indicates that

she didn’t wear shoes (so it had to be warm

enough) and that she hadn’t been outside in

bare feet “for months”.

Evaluative

The reader needs to use

information from the text

and their own world

experiences to form a

judgment.

The question might sound like this:

Do you think (character in the text) made

the right choice for her family? Explain

using text evidence.

Jennifer Arenson Yaeger Foundations of Reading Study Guide 2018

50

Before-During-After Reading Strategies

13

Before Reading:

The reader develops a plan of action by:

• Activating and building upon prior knowledge and experiences

• Predicting what text is about based on text features, visuals, and text type

• Setting a purpose for reading

An Anticipation Guide is an example of a Before Reading Strategy.

During Reading:

The reader maintains and monitors a plan of action by:

• Connecting new texts with prior knowledge and experiences

• Checking predictions for accuracy

• Forming sensory images

• Making inferences

• Determining key vocabulary

• Interpreting the traits of main characters

• Self-monitoring own difficulty in decoding and comprehending text

• Interpreting diagrams, maps, and charts

• Posing how, why and what questions to understand and/or interpret text

• Recognizing cause-effect relationships and drawing conclusions

• Noticing when comprehension problems arise

A Character Map is an example of a During Reading Strategy.

After Reading:

The reader evaluates a plan of action by:

• Discussing accuracy of predictions

• Summarizing the key ideas

• Connecting and comparing information from texts to experience and knowledge

• Explaining and describing new ideas and information in own words

• Retelling story in own words including setting, characters, and sequence of important events

• Discussing and comparing authors and illustrators

• Reflecting on the strategies that helped the most and least and why

A Semantic Map is an example of an After Reading Strategy.

Jennifer Arenson Yaeger Foundations of Reading Study Guide 2018

51

Literacy Guide:

14

STRATEGIES FOR SUCCESSFUL READERS AND WRITERS: Before,

During and After Reading

Successful readers and writers need to learn and practice a number of strategies to use Before,

During, and After Reading.

The following pre-reading activities can help students to:

• Activate Background Knowledge and Make Connections

• Stimulate Predictions

• Form a Purpose for Reading

Predicting:

• Examine the cover illustration (if there is one) and read the title of new book. Ask child to

predict what it might be about based on either the cover picture, the title, or both. If the title

and illustration are not helpful in giving the student a sense of what the story is about, you

can provide a brief summary of the book. For example, when looking at a book with a

picture of a cat on the front, you can say: “This story is about a cat that moves to a new

house and has some adventures while trying to make new friends.”

Activating Background Knowledge:

• Ask the student to tell you what he or she knows about the subject of the story or if he or

she has had similar experiences, or heard or read a story like this or by same author. “You

said you have a cat. Tell me what your cat does all day and who its friends are. What kind of

friends do you think the cat in this book might find?” if the topic is totally unfamiliar,

reconsider book choice, or take extra time to build the necessary background knowledge

through some kind of concrete experiences. For example, if you choose a book about a farm

and the student has never been to a farm you may want to begin by looking at pictures of

farms and farm animals, and having a brief discussion about what kinds of things happen on

farms: what animals live there, what things grow on farms, etc.

Conducting Picture Walk:

• With Emergent and Early readers conduct a “Picture Walk” through the book, or chapter,

by covering the print, and encouraging or guiding the student in a discussion of what could

be going on based on the pictures. If there is vocabulary that may not be familiar to child

such as “cupboard” or “bonnet” point the words out and explain them in connection with

the teeny tiny woman is putting on her hat, except in this book it’s called a ‘bonnet’ (pointing

to the word) which is another word for hat. She is putting on her teeny tiny bonnet. Do you

think she is getting ready to go somewhere? “In your discussion of the pictures, be sure to

use as much of the actual book language as possible, especially if there are repeated patterns

or refrains. (The Teeny Tiny Woman, Barbara Seeling).

Jennifer Arenson Yaeger Foundations of Reading Study Guide 2018

52

Noticing Structure of the text:

• Where appropriate, point out or help the child notice the structure of the text and connect it

with other similarly structured texts heard or read. “Yes, this is a fairy tale. We’ve read

several fairy tales together. What do you know about fairy tales? What have you noticed that

is the same about the three tales we read?”