WHAT IS THE EVIDENCE ON TOP-DOWN AND BOTTOM-UP

APPROACHES IN IMPROVING ACCESS TO WATER,

SANITATION AND ELECTRICITY SERVICES IN LOW-INCOME

OR INFORMAL SETTLEMENTS?

SYSTEMATIC REVIEW [NOVEMBER 2016]

2

The authors of this report are

Thillai Rajan Annamalai (Indian Institute of Technology Madras, India)

Ganesh Devkar (CEPT University, Ahmedabad, India)

Ashwin Mahalingam (Indian Institute of Technology Madras, India)

Solomon Benjamin (Indian Institute of Technology Madras, India)

Sudhir Chella Rajan (Indian Institute of Technology Madras, India)

Akash Deep (Harvard Kennedy School, Harvard University, US)

Funding

This is an independent report commissioned and funded by the Research and Evidence Division in the

Department for International Development. This material has been funded by UK aid from the UK

Government, however, the views expressed do not necessarily reflect the UK Government’s official

policies

Acknowledgments

We thank our host institutions; the EPPI-Centre; our funder, the South Asia Research Hub, Government

of UK; our peer reviewers, Dr Mukdarut Bangpan, Ms Kelly Dickson and Mr Jeff Brunton for regular

discussions; and our project associate, Mr M.S. Elayaraja.

Conflicts of interests

None of the authors has any financial interest in this review topic, nor have they been involved in the

development of relevant interventions, primary research, or prior published reviews on the topic.

Contributions

The opinions expressed in this publication are not necessarily those of the EPPI-Centre or the funders.

Responsibility for the views expressed remains solely with the authors.

Citation

Annamalai TR, Devkar G, Mahalingam A, Benjamin S, Rajan SC, Deep A (2016) What is the evidence on

top-down and bottom-up approaches in improving access to water, sanitation and electricity services

in low-income or informal settlements? London: EPPI-Centre, Social Science Research Unit, UCL

Institute of Education, University College London.

Picture

Photos by World Bank Photo Collection and SuSanA Secretarlat; permitted with licence

https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0/legalcode

© Copyright

Authors of the systematic reviews on the EPPI-Centre website (http://eppi.ioe.ac.uk/) hold the

copyright for the text of their reviews. The EPPI-Centre owns the copyright for all material on the

website it has developed, including the contents of the databases, manuals, and key wording and data-

extraction systems. The centre and authors give permission for users of the site to display and print the

contents of the site for their own non-commercial use, provided that the materials are not modified,

copyright and other proprietary notices contained in the materials are retained, and the source of the

material is cited clearly, following the citation details provided. Otherwise, users are not permitted to

duplicate, reproduce, republish, distribute, or store material from this website without written

permission.

3

SUMMARY

This systematic review of urban planning studies in developing countries found that top-down efforts

are ineffective for connecting populations to centralised water, sanitation or electricity services.

Bottom up, participatory approaches are effective for local sanitation solutions, but not for water

supply or connectivity to other services.

Services provided by public or private agencies through centralised planning and implementation (top-

down) appeared effective in individual studies for connecting populations to water, sanitation and

electricity. However, where studies were sufficiently similar to justify pooling findings in a statistical

meta-analysis, this conclusion was not confirmed. Qualitative synthesis of contextual factors suggest a

need for the customisation of solutions to meet local needs, and better delivery of services by

alternative/non-government service providers.

Participatory (bottom-up) approaches adopted by NGOs and CBOs suit the construction and

maintenance of toilets, which can be standalone, and statistical meta-analysis confirms their

effectiveness for individual but not community toilets. Although studies of bottom-up approaches to

improving water access appeared positive more often than studies of top down approaches, this

difference was not statistically significant in a meta-analysis. Moreover, bottom-up approaches suffer

from problems of scaling-up. Replication of successful models may not always be possible, since the

same conditions may not be present in different locations.

Neighbourhoods without security of tenure are rarely served well top-down. Bottom-up approaches

are also limited in this context, and also in Africa where efforts may be hampered by particularly

modest levels of economic development. Public-private partnerships show promise for top-down

approaches to improving water supply. Bottom-up, NGO led initiatives for improving water supply

need the cooperation and support of the public sector.

INTRODUCTION

This systematic review examines the evidence on the effectiveness of different urban-planning

approaches in providing access to water, sanitation and electricity services in low-income or informal

settlements in Low- and Middle-Income Countries (LMICs). The study was funded by the Department

for International Development (DFID) of the UK government and conducted by the Indian Institute of

Technology Madras. The review addresses the following question: What is the evidence on what makes

an effective urban-planning framework for improved access to water, sanitation and electricity services

in low-income or informal settlements? More specifically, the review seeks answers to the following

questions:

1. How effective are the top-down and bottom-up approaches in improving access to water supply,

sanitation and electricity services in low-income or informal settlements in LMICs?

2. Under what circumstances do these approaches deliver better results? Why?

3. What are the strengths and limitations of these two approaches in respect of providing access to

basic services in low-income areas and informal settlements?

This brief is designed to provide an overview of the key evidence identified in the systematic review

and to assist policymakers and researchers in assessing the strengths and limitations of the different

4

service-delivery approaches in slums. For the purpose of this review, service-delivery approaches were

classified into two categories: top-down and bottom up. Services provided by the government or

government agencies, which are usually characterised by centralised planning and implementation,

were classified as top-down. Services provided by Non-Governmental Organizations (NGOs) and

Community-Based Organizations (CBOs), or other small-scale service providers, which are characterised

by a higher degree of decentralised planning and implementation, were classified as bottom-up. In

reality, there may be very few purely top-down or bottom-up approaches, since the majority of the

programmes fall in between these two polar-opposite approaches, with varying degrees of

decentralisation. However, classifying in a review the service provision as either top-down or bottom-

up clusters the evidence in terms of which service provider has played a dominant role.

SUMMARY CONCLUSIONS

The explorative and statistical analysis of quantitative evidence suggest a bottom-up approach can be

more effective in increasing access to water and sanitation, particularly in the provision of toilets

compared to a top-down approach. Although explorative analysis initially suggested that taking a top-

down approach can be more effective in increasing the supply of electricity, the finding was not

confirmed when statistically pooling the evidence. Qualitative synthesis of contextual factors

influencing improvement in the supply of water, sanitation and electricity, suggest a need for the

customisation of solutions to meet local needs, and better delivery of services by alternative/non-

government service providers. Evidence of approaches taking a bottom-up approach has shown some

improvement in outcomes across multiple dimensions of access, such as connectivity, adequacy and

affordability, whereas top-down approach has predominantly focused on connectivity. The impact of a

bottom-up approach has been least evident in Africa. This suggests that the success of planning

approaches can depend upon different social and political context. Such that, in relatively difficult socio-

economic environments, across different LMIC countries (often characterised by different levels of

poverty, inadequate infrastructure, weak economy and governance, poor institutional capacity, and

absence of civil-society participation) bottom-up approaches requires continued support from other

actors, such as the government, to ensure the delivery of more positive results.

Community participation and tenure security emerged as two important moderators affecting

outcomes. A bottom-up approach was more amenable in facilitating community participation and in

engaging with the poor settlements. They were even more effective when there was security of tenure.

Political commitment also played an important role in affecting outcomes. Strong commitment from

the government in the form of universal access, pro-poor policy reform, or specific schemes to improve

access to the poor, also played an important role in improving access to slums and low-income

settlements.

SYSTEMATIC REVIEW APPROACH

This review synthesises the evidence on access, since it forms an important element in achieving the

Millennium Development Goals (MDGs). While, traditionally, access has been synonymously used to

mean connectivity, we have adopted a more holistic definition of access that considers the following

dimensions: connectivity, affordability, adequacy, effort and time, and durability.

The steps followed for the review were:

Formulating exclusion and inclusion criteria to determine the studies to be included in the

review.

5

Deciding on the sources and the search methods (search phrases) to be used to identify the

studies.

Managing the shortlisted and identified studies using EPPI-Reviewer.

Quality appraisal of the studies identified for inclusion in the review.

Synthesising the evidence in the included studies. Given the heterogeneity of the studies,

multiple methods were used in the synthesis: numerical summary, meta-analysis and textual

narration.

SUMMARY MAP OF EVIDENCE

A total of 104 studies met the exclusion, inclusion, and quality-appraisal criteria and were included in

the analysis. These studies covered six geographical regions, 34 countries, and 103 cities. Studies from

Asia were the most numerous, followed by those from Africa and South America. Dhaka occupied the

top slot in the list of cities, followed by Mumbai, Ahmedabad, Jakarta, and New Delhi. A total of 66% of

the studies were from journals, whereas 34% of the studies were from grey literature. The highest

number of studies was for water (77), followed by sanitation (64) and electricity (31).

OUTLINE OF THE EVIDENCE

Exploratory analysis

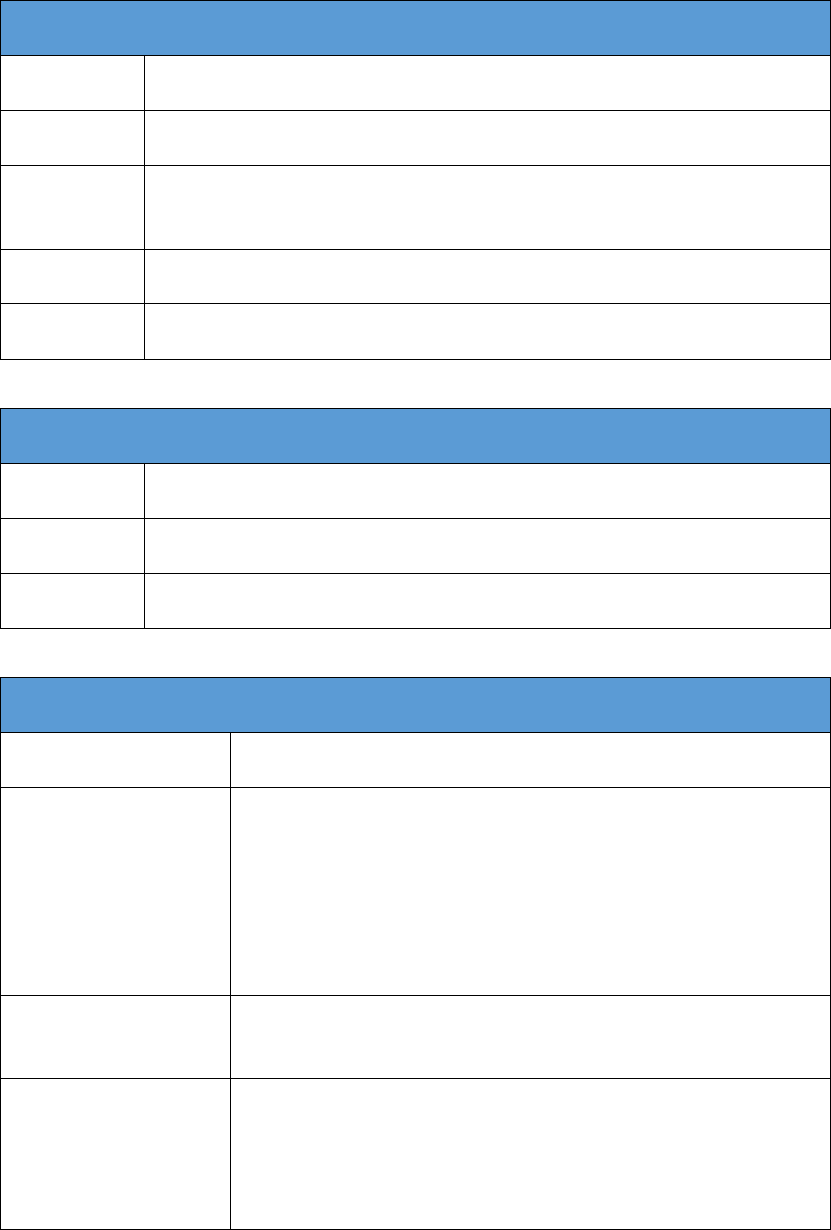

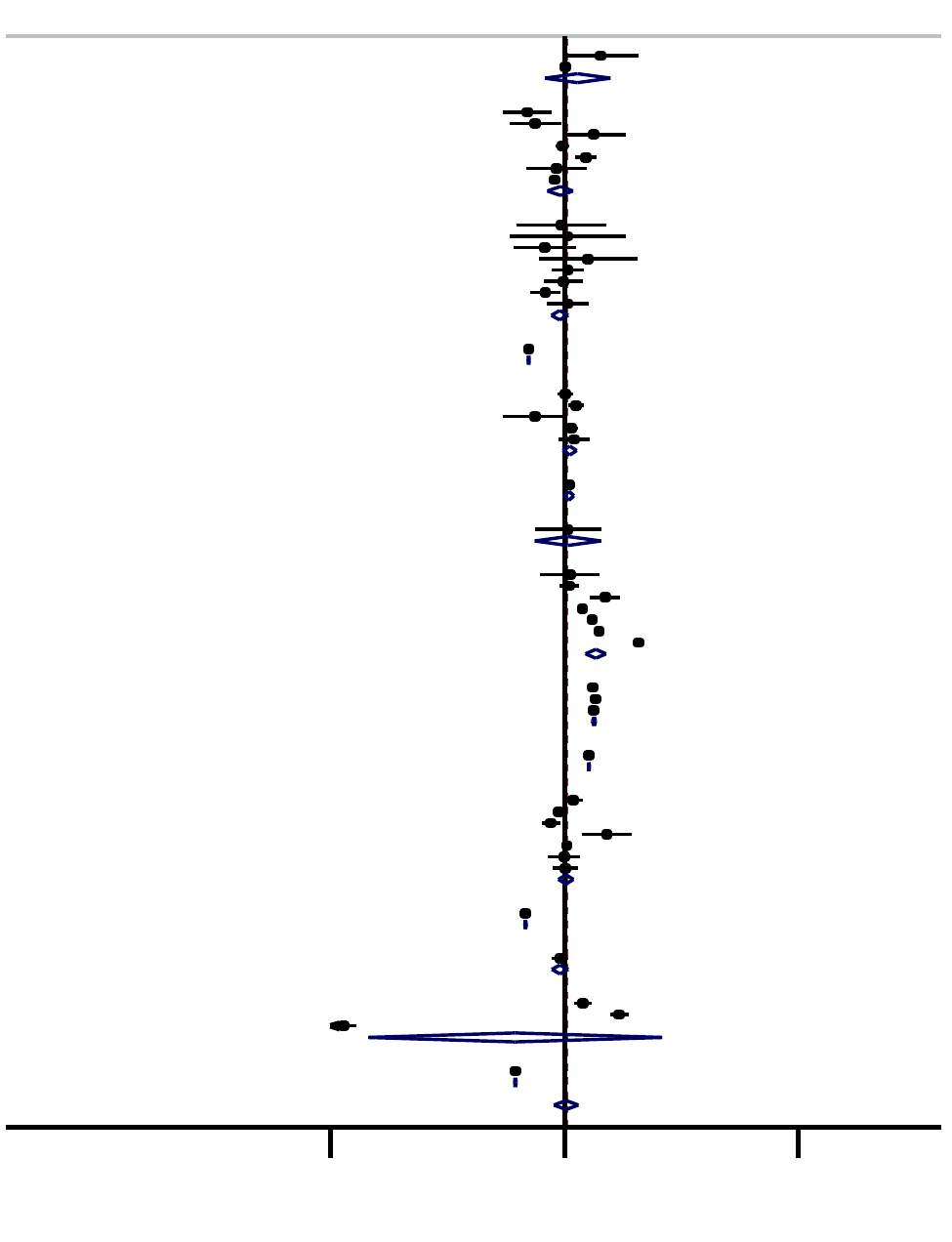

Findings from an exploratory analysis, suggest that overall, access to water can be improved when a

bottom-up approach is adopted, compared to a top-down approach. Prior to conducting a meta-

analysis, exploration of the data indicated that there was improvement in access in 40% of cases using

a top-down approach, whereas, in the bottom-up approach, it was 55%. Connectivity has been used as

the primary measure of access, as seen by the number of outcome data in both top-down and bottom-

up approaches. The number of outcome measures on other dimensions of access, such as adequacy,

affordability, effort and time, and durability, have been considerably lower. A bottom-up approach

indicated improvements across multiple dimensions of access, whereas the improvement in the top-

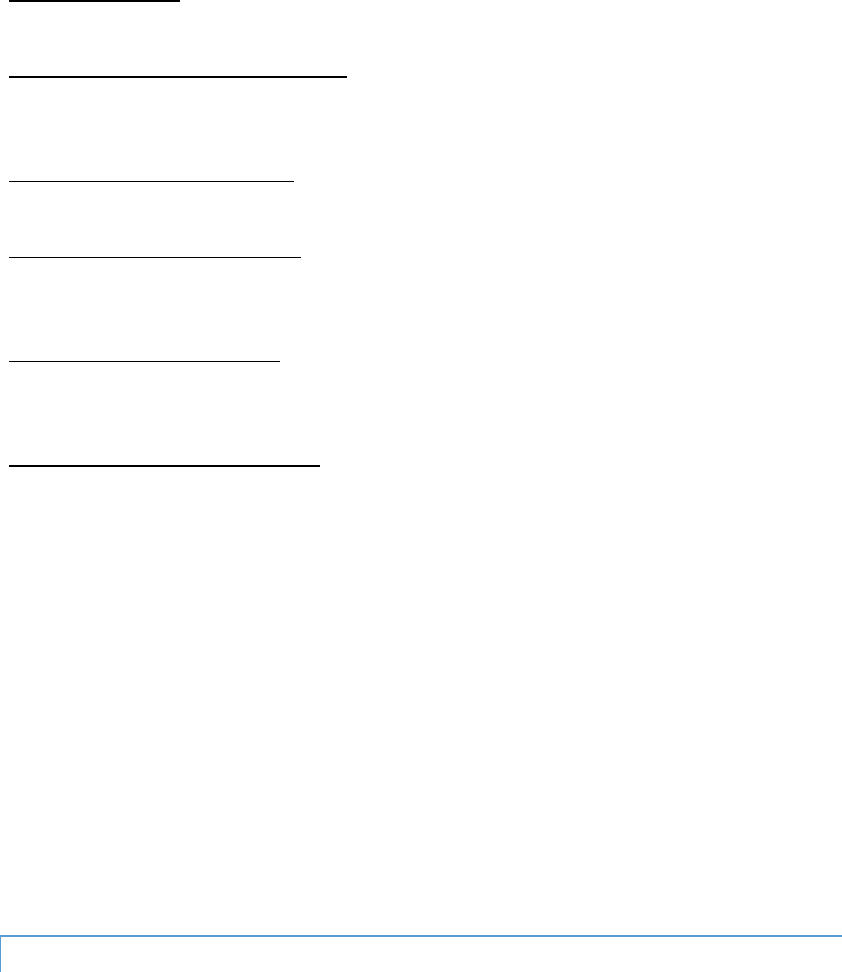

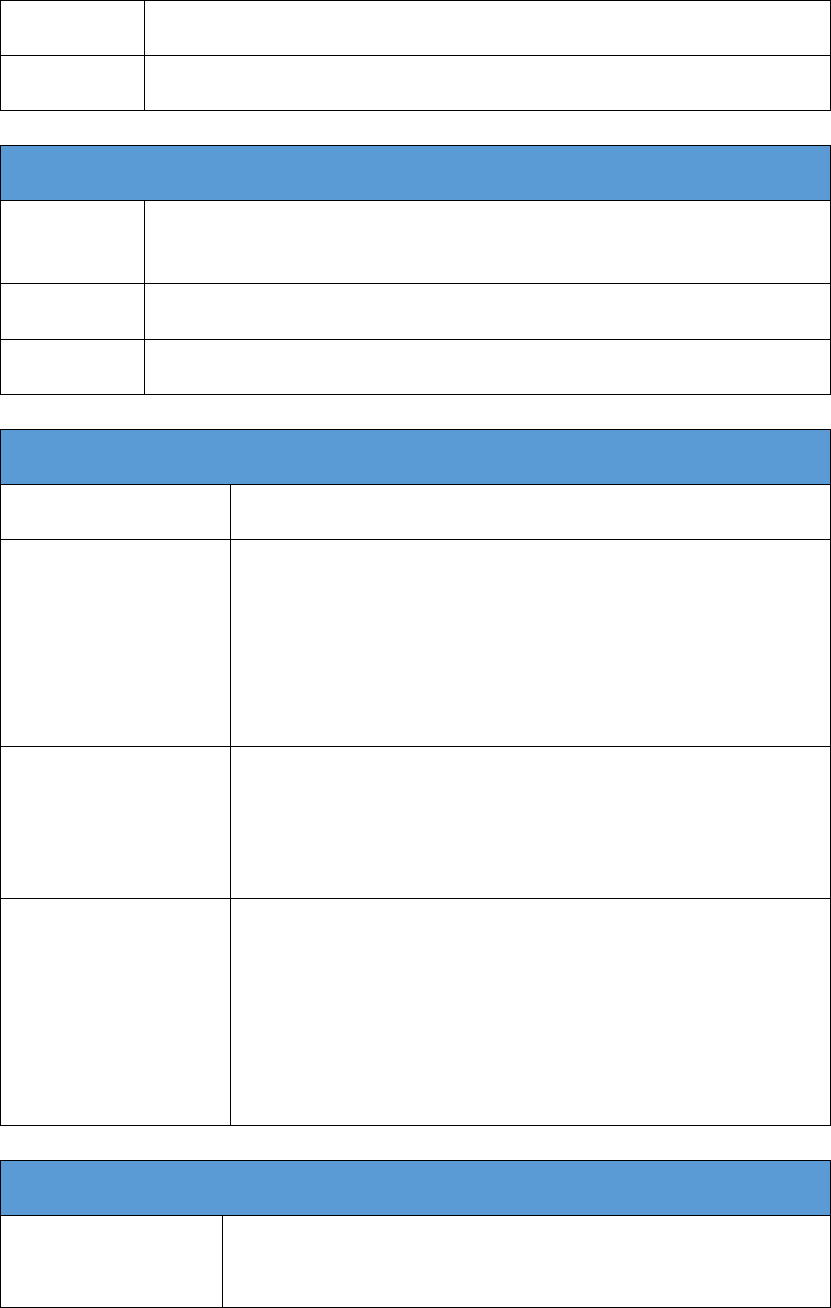

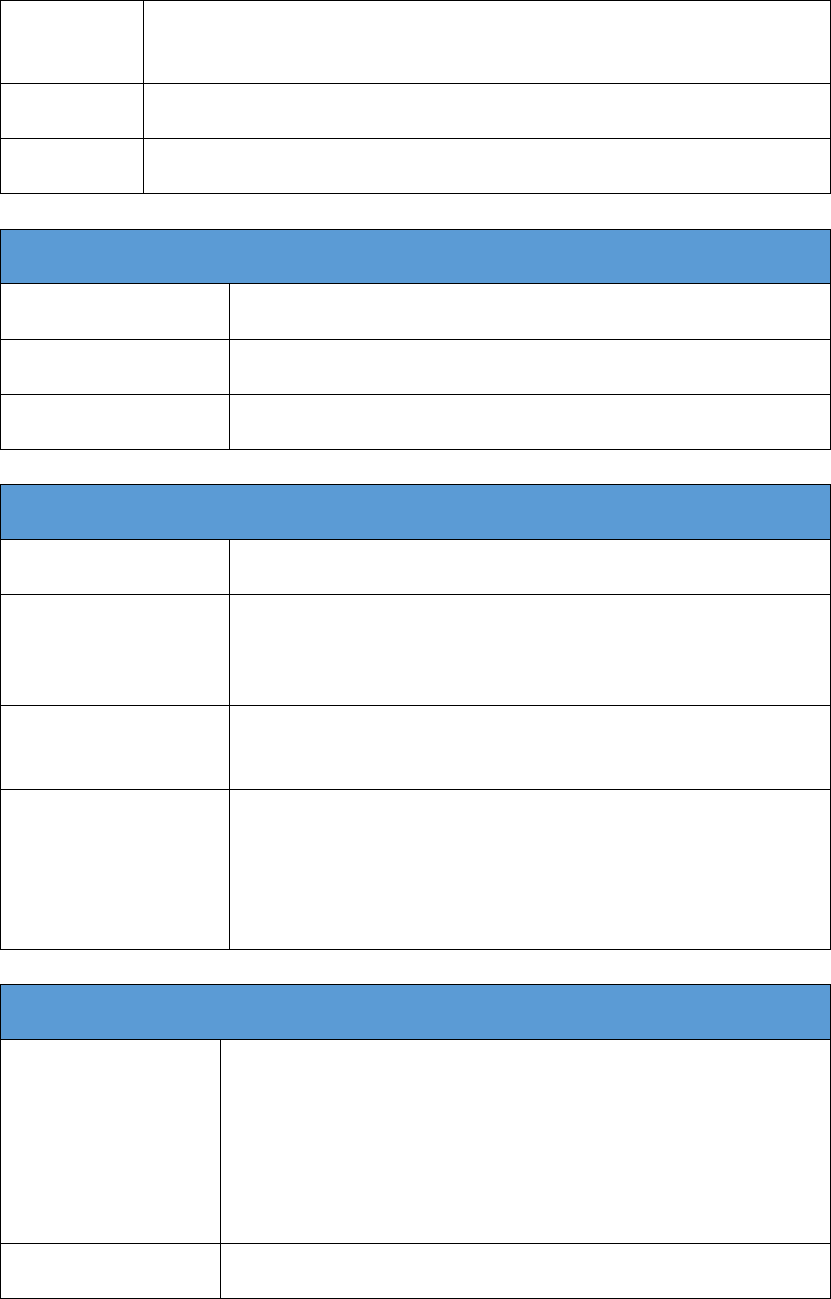

down approach was seen primarily on connectivity (see Figure 1, below). We tested these findings on

improvements to connectivity using statistical meta-analysis (see below) and made additional insights.

6

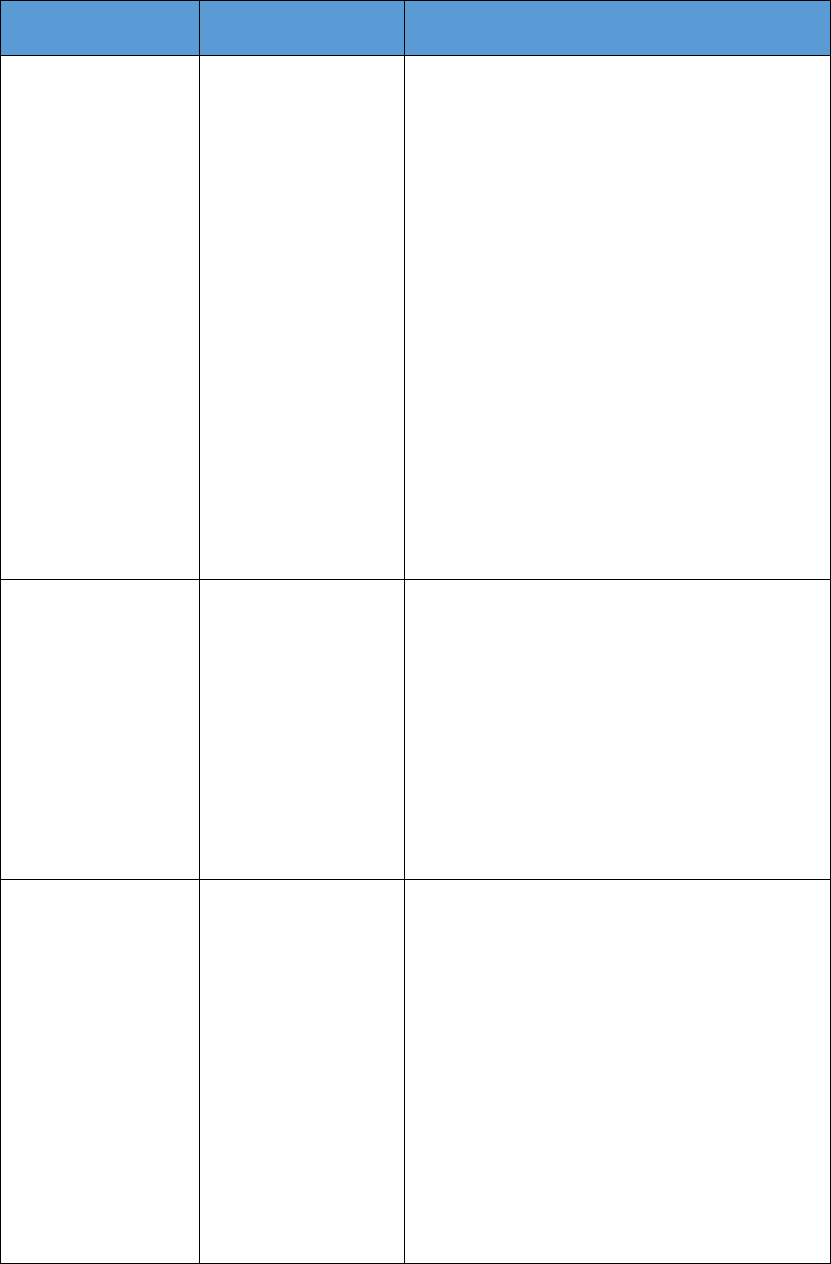

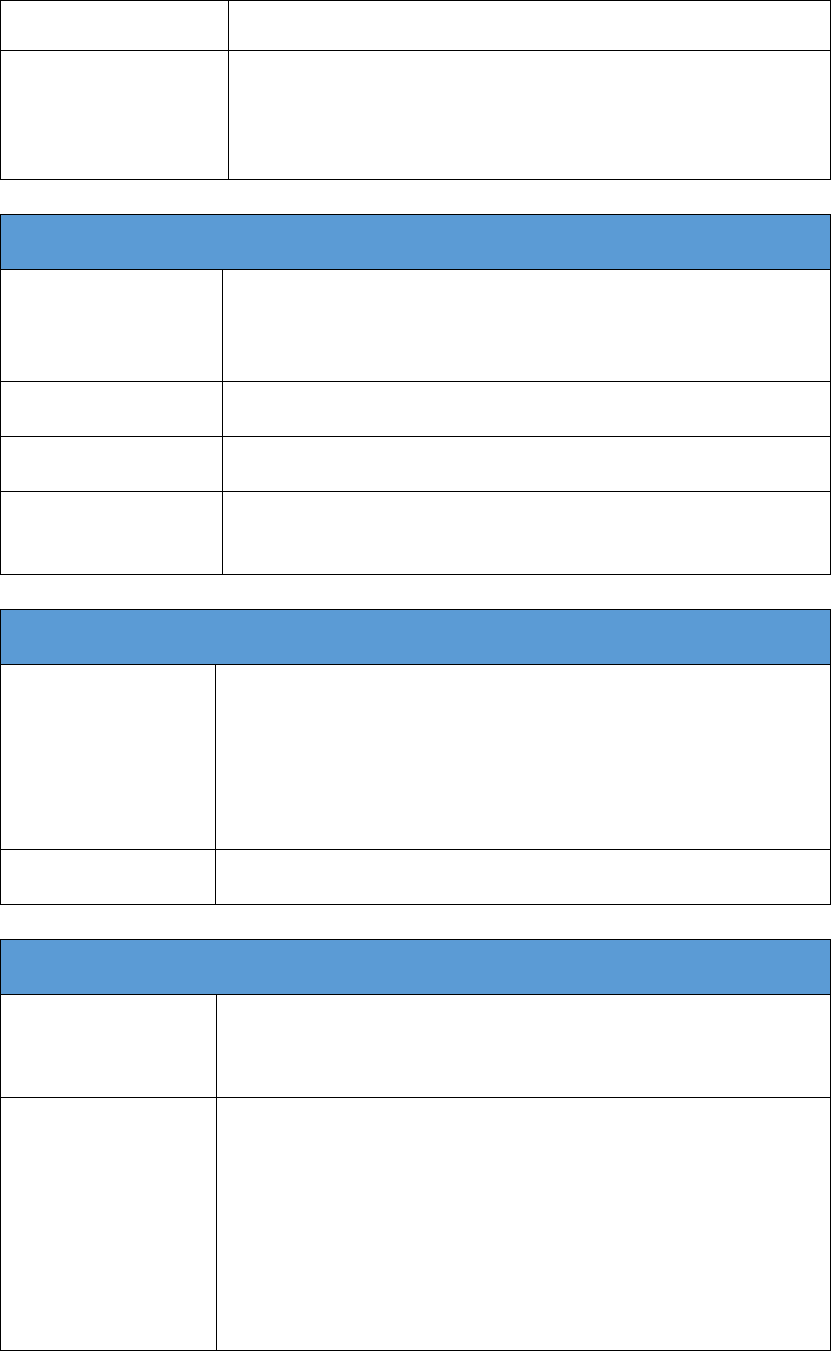

Fig 1: Proportion of findings that show improvement in different dimensions of access

Meta-analysis

Meta-analysis results provided an aggregate quantitative measure, based on the findings from the

individual studies. This aggregate measure, if it had a value greater than 1 and was statistically

significant, indicated an improvement in connectivity, comparing between bottom-up and topdown

approaches. However, if the aggregate measure was less than 1 and statistically significant, it indicated

a decline in connectivity. If it was not statistically significant, then there was no change to the status

quo in connectivity as a result of using a bottom-up approach.

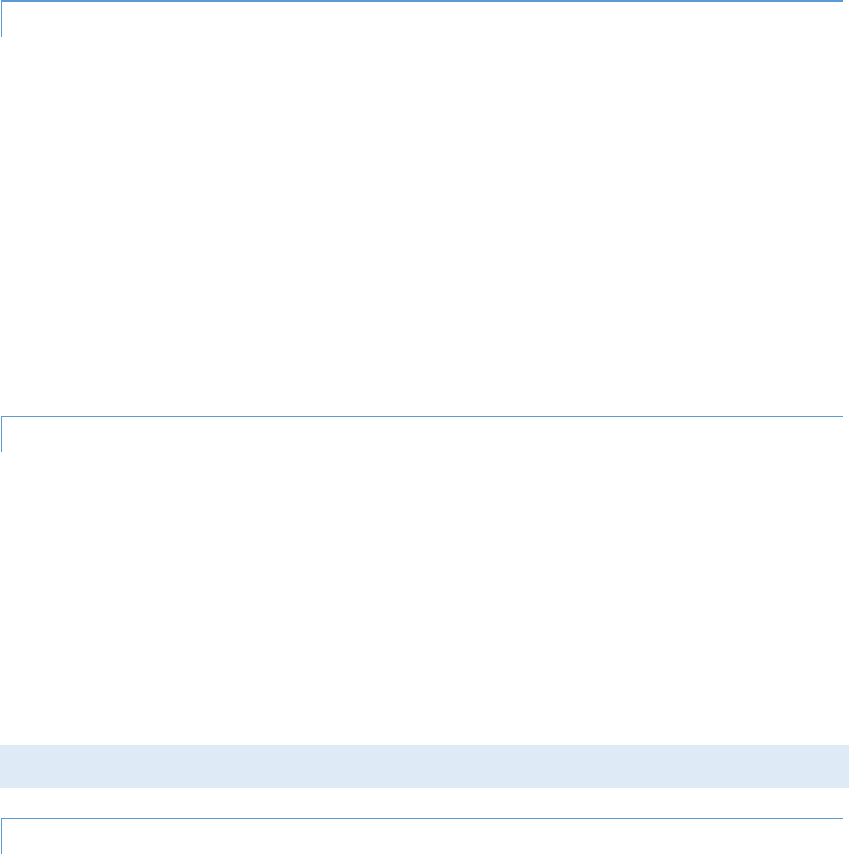

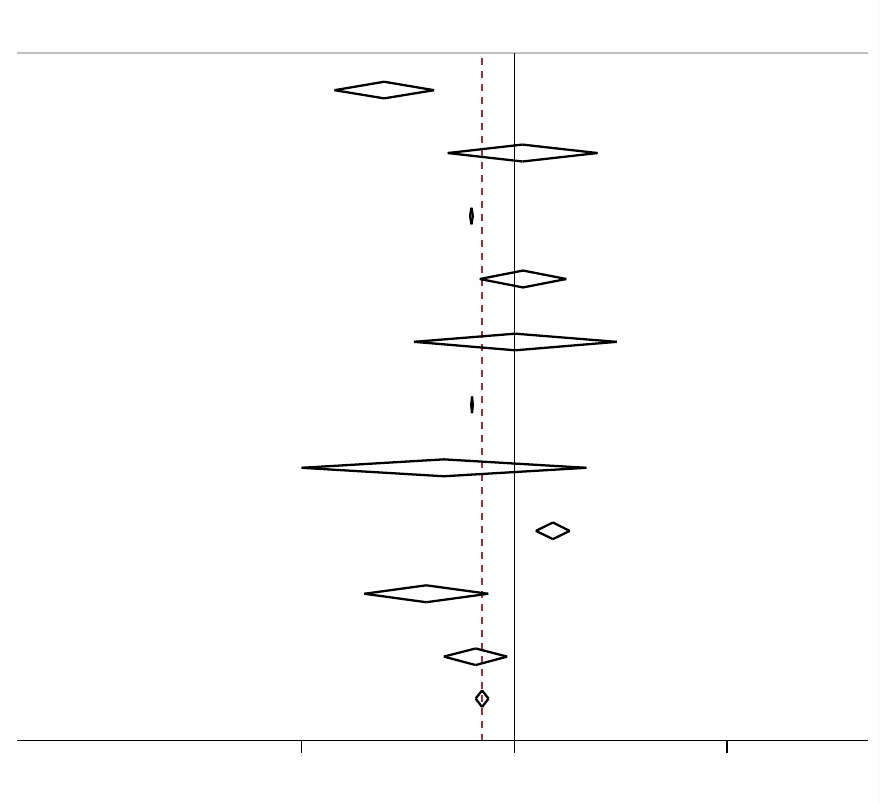

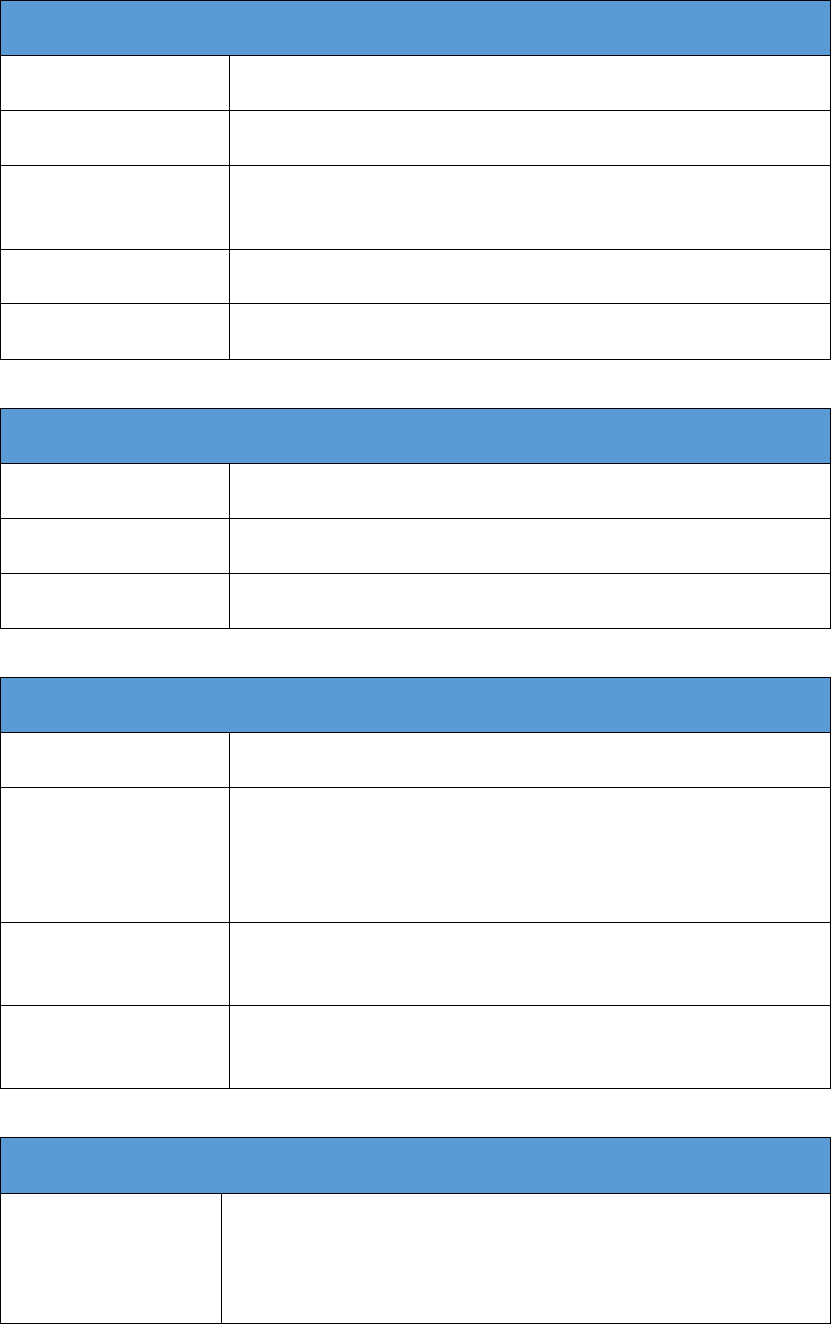

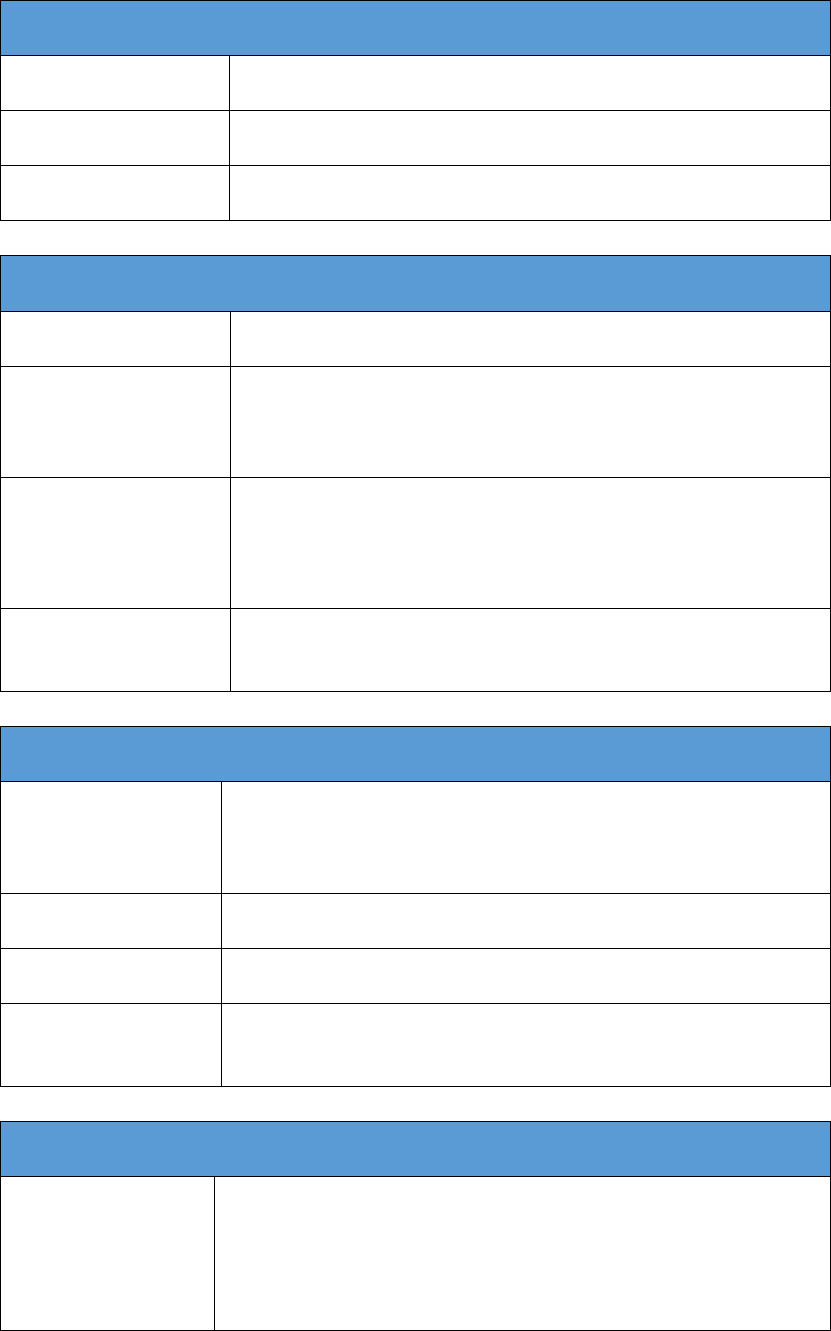

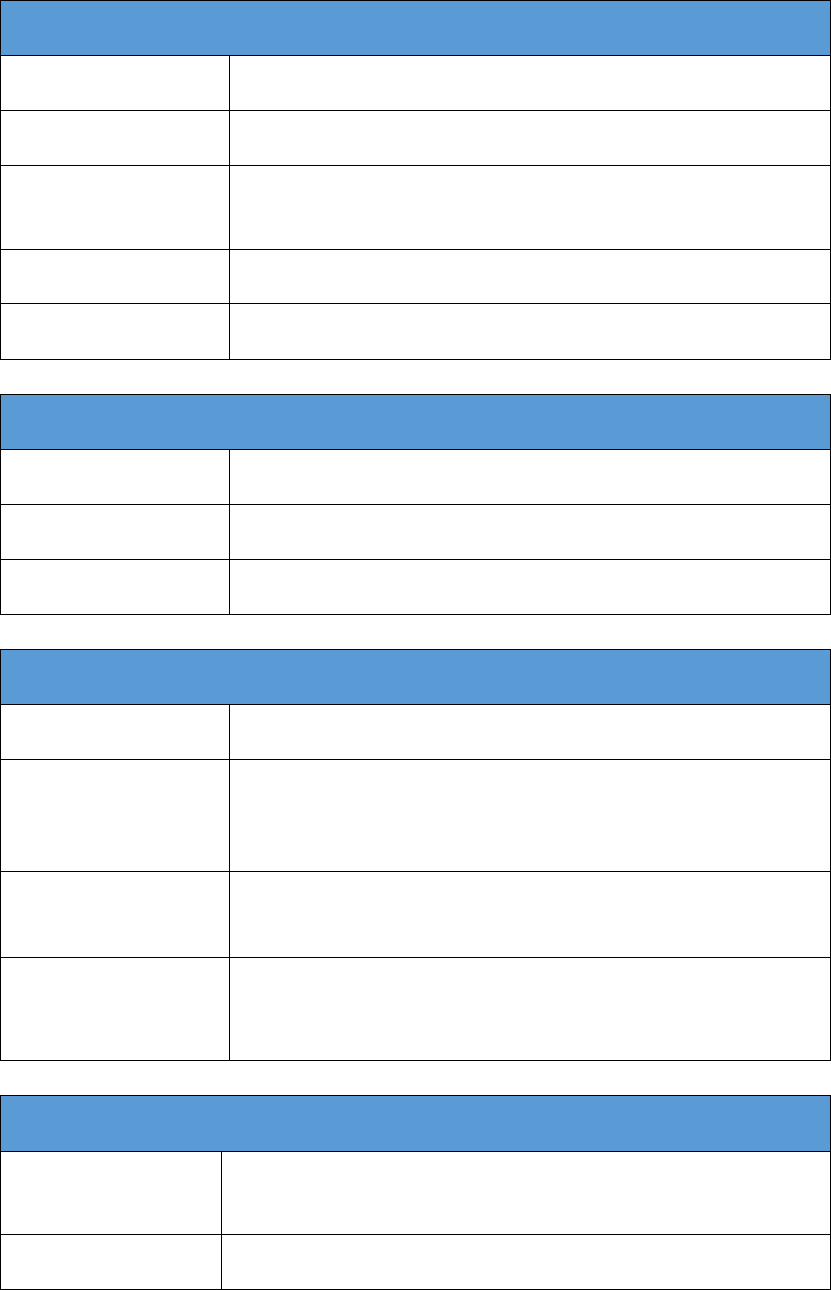

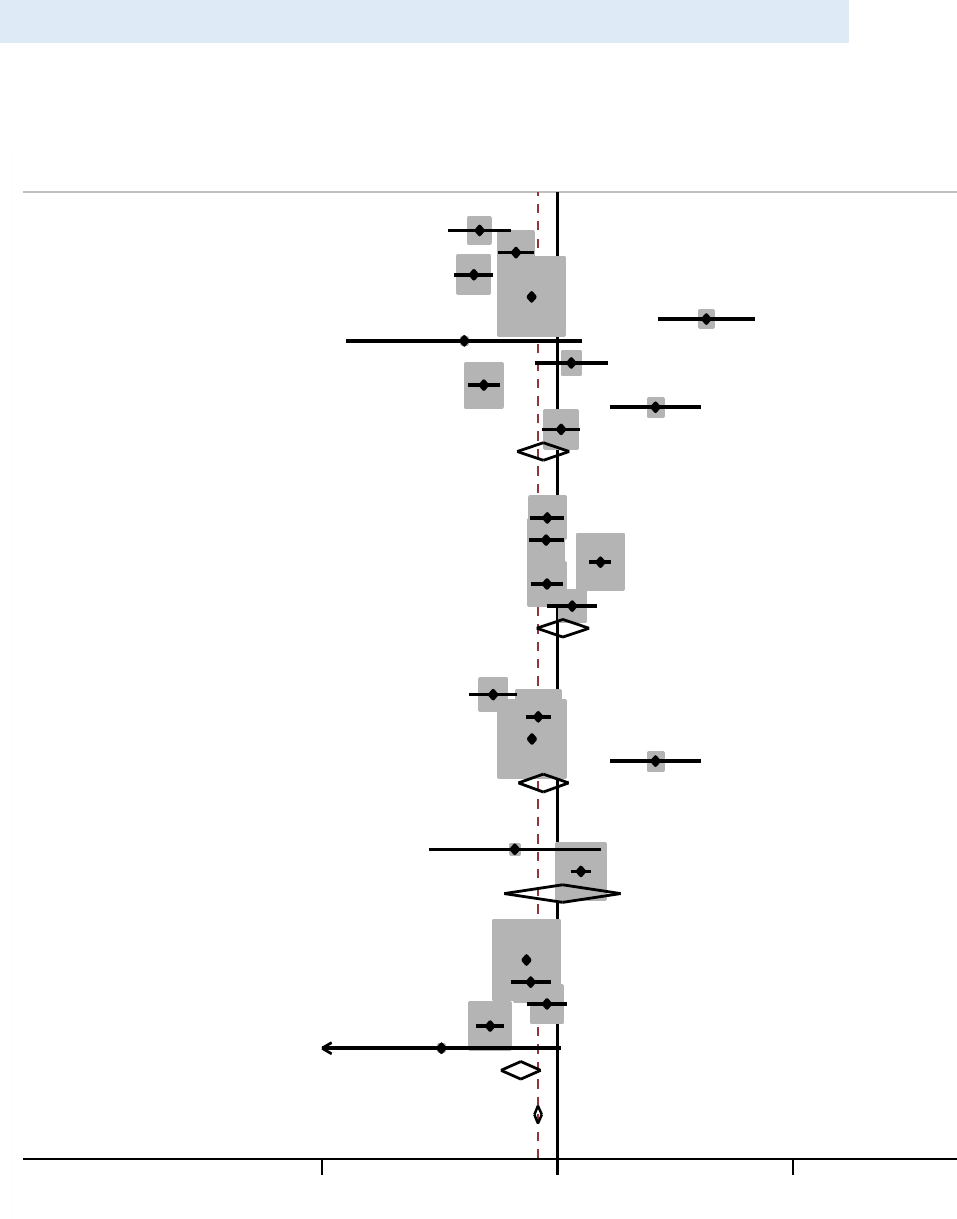

Figure 2, below, shows the effectiveness of a bottom-up approach on connectivity across regions and

facilities. Among all the facilities, it can be seen that a bottom-up approach has also been effective only

in the provision of individual toilets. Except in the case of Africa, a bottom-up approach has led to an

improvement in access to individual toilets in all regions. A possible reason for this trend is the modest

level of economic development characteristics of some African countries as compared to other

geographical regions. Construction of individual toilets also requires substantial investment from

households, which is a deterrent in poor slum communities. However, the evidence in Asia, South

America and Central and North America suggests that a bottom-up approach help to create conditions

that result in a greater number of households constructing toilets. Analysis of the evidence by region

shows that a bottom-up approach has led to a decline in connectivity in Central and North America,

except in the case of individual toilets. However, the finding is limited by the low number of studies in

the region.

Overall, our findings help us to conclude that a bottom-up approach has been able to achieve

improvements in only a few instances, indicating the limitations of their effectiveness as an intervention

measure to improve connectivity.

53%

23%

25%

24%

20%

57%

52%

36%

72%

58%

0%

10%

20%

30%

40%

50%

60%

70%

80%

Connectivity Adequacy Affordability Effort and time Durability

Evidences indicating improvement

Top-down approaches Bottom-up approaches

7

Legend

The numerical values show the aggregate quantitative measure obtained from meta-analysis. Blank

values indicate the absence of evidence in the respective regions and facilities

Fig 2: Connectivity and bottom-up approach: by type of facility and region

SUMMARY OF KEY FINDINGS

A narrative summary of the key findings by individual sector is provided in more detail below. This

summary draws on both quantitative evidence of impact from the exploratory numerical analysis and

statistical meta-analysis. Further analysis of qualitative evidence to provide an account of moderating

factors influencing implementation of top-down and bottom-up approaches is also presented.

WATER SECTOR

Multiple approaches prevail in water supply for urban slums — from public provision of supply, to

private and NGO-driven delivery of services. Water supply is characterised by the presence of both

individual and community connections. While there may be a preference for individual connections on

the part of policymakers and community members, spatial, legal and financial constraints limit the

extent of coverage.

The exploratory analysis revealed that there was a higher proportion of outcome measures indicating

an improvement in access to water using a bottom-up approach (53%) as compared to under a top-

down approach (42%). The finding from the meta-analysis also indicates a non-statistically significant,

but positive trend towards using a bottom-up approach in improving access to water.

Indicates improvement

Indicates decline

No change to status quo

8

Qualitative textual-narrative analysis shows that the key reasons behind the poor performance of the

top-down approach were government mismanagement, unclear responsibility among government

agencies, lack of a pro-poor policy, poor finances and weak legal mandate for network expansion in

slums, and inappropriate pricing policies, which affect the affordability of slum-dwellings The bottom-

up approach, however, was able to mobilise community members to participate, physically and

financially, in the service-delivery process. This afforded a sense of ownership over the infrastructure

by community members, which resulted in positive outcomes. For instance, NGO involvement with

slum communities in Zambia led to the creation of a Water Trust, which helped communities address

their water shortages. Similarly, studies have shown the intermediary role played by NGOs in

Bangladesh and Nepal in facilitating water connections in slums. However, scaling-up of successful

interventions and replication of them in other locations may not be possible, with bottom-up approach

which seek to address context-specific issues, which may not be present in different locations, limiting

their transferability.

SANITATION SECTOR

Access level to sanitation is the poorest among the three sectors. Sanitation services include sewerage

systems and access to toilets, neither of which is readily available in slums. Open defecation (such as

disposal of feces in means other than a toilet) are few of the common practices in slums that have a

detrimental impact on health and hygiene.

The effectiveness of the top-down approach has been the poorest in sanitation, with only 28% of the

evidence showing an improvement. However, in the bottom-up approach, 55% of the outcome

evidence have reported an improvement. Meta-analysis results confirmed this finding, showing that

the bottom-up approach has statistically significant improvement in access to sanitation.

Qualitative analysis reveals, that apart from the lack of government willingness to extend network

coverage in slums, there are three main factors which emerge as constraints on the provision of

sanitation in slums: 1) The issue of tenure security; 2) lack of maintenance of community infrastructure;

and 3) poor participation of stakeholders in the planning and design of facility. NGOs and CBOs have

been able to address the last two concerns by adopting a decentralised approach and engaging

community members in the planning, design and maintenance of community toilets. The Orangi case

study from Pakistan is an example of the benefits of community participation, which have resulted in

substantial improvements in water and sanitation infrastructure in slums. Residents of Orangi, with the

help of a local NGO, took the financial responsibility for the construction of smaller feeder pipes for

water and sewerage within the community, while the government agreed on connecting the slum to

the city-wide water and sewerage network. As a result of this partnership, residents could get

household-level connections, as well as connections to the city-wide network, which proved to be

beneficial to all stakeholders. Community-sanitation initiatives in the cities of Mumbai, and Trichy,

India, also highlight the efforts of NGOs and CBOs in the construction of community toilets in urban

slums.

9

ELECTRICITY SECTOR

Access levels to electricity have been the highest of the three basic services studied in this review.

However, most of the slum-dwellers access electricity through illegal connections, either because of

high up-front costs or the high cost of power.

The exploratory analysis, suggested that the incidence of using a bottom-up approach has been the

lowest in respect of the electricity supply: less than 10% of the outcome evidence in the bottom-up

approach were in electricity. When conducting meta-analysis, the results showed that involvement of

non-state service providers has not had the desired effect in terms of improving access to electricity;

despite the narrative analysis indicating that access to electricity can improve with tenure security and

strong political backing. Interventions that have a pro-poor approach and those that involve community

participation in the service-delivery process have shown an increase in connectivity. Case studies such

as the Depressed Area Electrification Program in Philippines, the accelerated electrification program in

Thailand, and the Slum Electrification Program in Ahmedabad, India, all point to the pro-poor approach

of the Government as improving access to electricity in slums. With the support of the Government and

by adopting innovative management practices and pricing methods, and by enlisting the support of

CBOs, utilities have addressed the problem of illegal connections, non-payment and theft.

MODERATING FACTORS

PARTICIPATION

Participation of the local community is an important moderator in influencing outcomes. The bottom-

up approach, however, does not automatically result in community participation. Project planning

should specifically include components that involve the local community in different stages of the

project life-cycle. Studies more often indicated an improvement in access when there was active

participation from the community. Meta-analysis results showed that the bottom-up approach, when

accompanied by active community participation, led to a significant improvement in access. In the

absence of community participation, a bottom-up approach was not effective. Community participation

helps service providers to understand the needs of the slum-dwellers and, subsequently, to tailor the

services to their requirements. This was clearly evident in the sanitation sector in several Asian

countries, such as Nepal, Bangladesh, India and Pakistan. Community participation, for example, helped

the service providers to factor in the needs of women and children during the construction of toilets

and subsequent maintenance, thereby leading to improved patronage of the facilities created.

TENURE SECURITY

Tenure security emerged as yet another moderator in impacting access to basic services. The legal

status of the slum determines the type of service provider and the service-delivery approach. Formal

slums, which are legally recognised and have security of tenure, enjoy a higher degree of connectivity

(56%), whereas informal slums, which lack legal recognition, have comparatively low levels of

connectivity (40%).

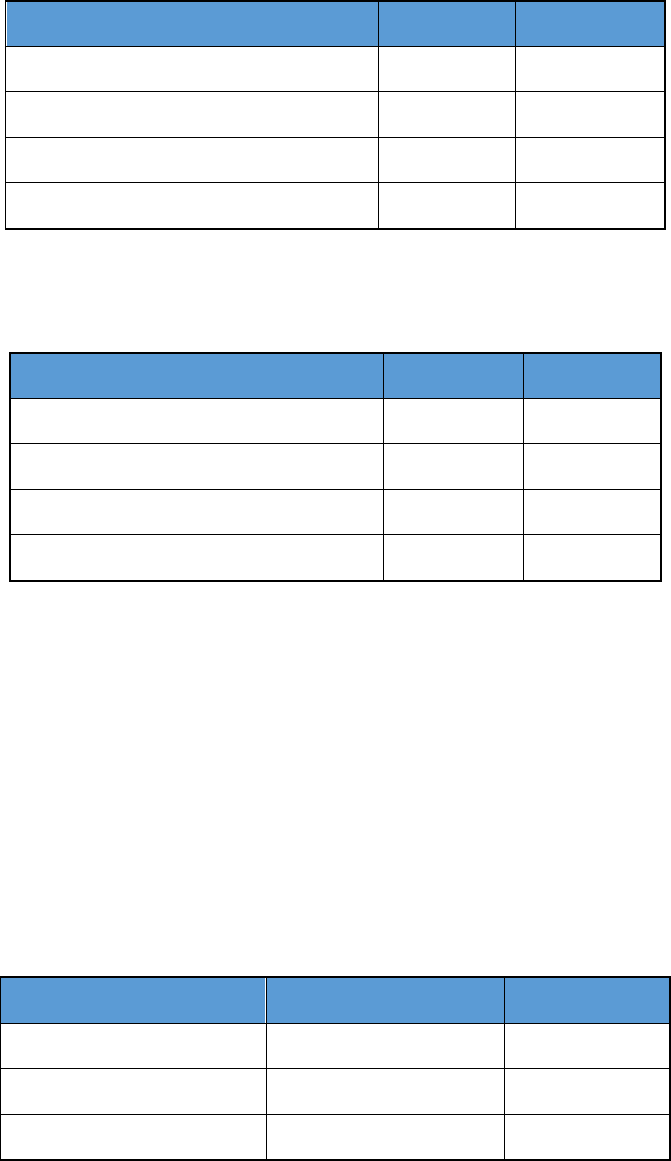

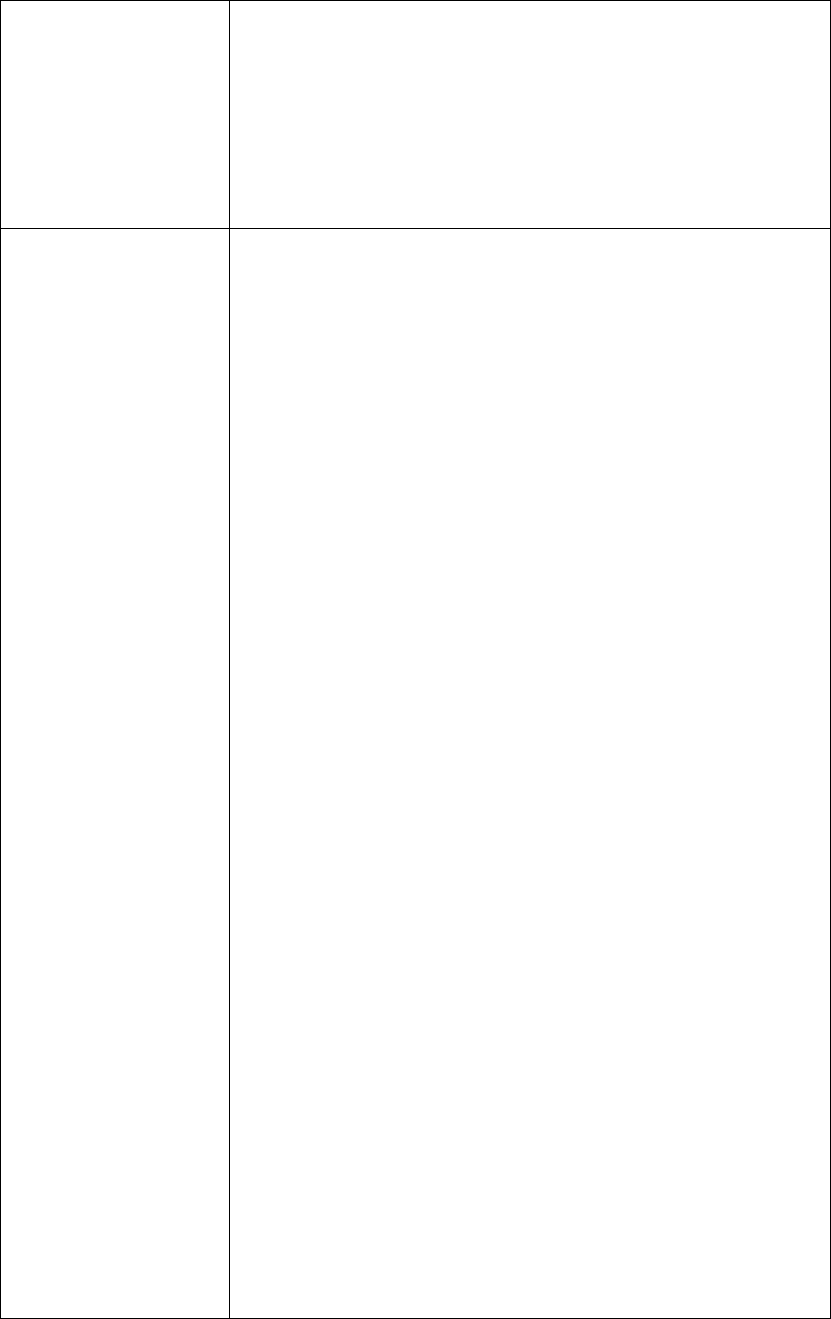

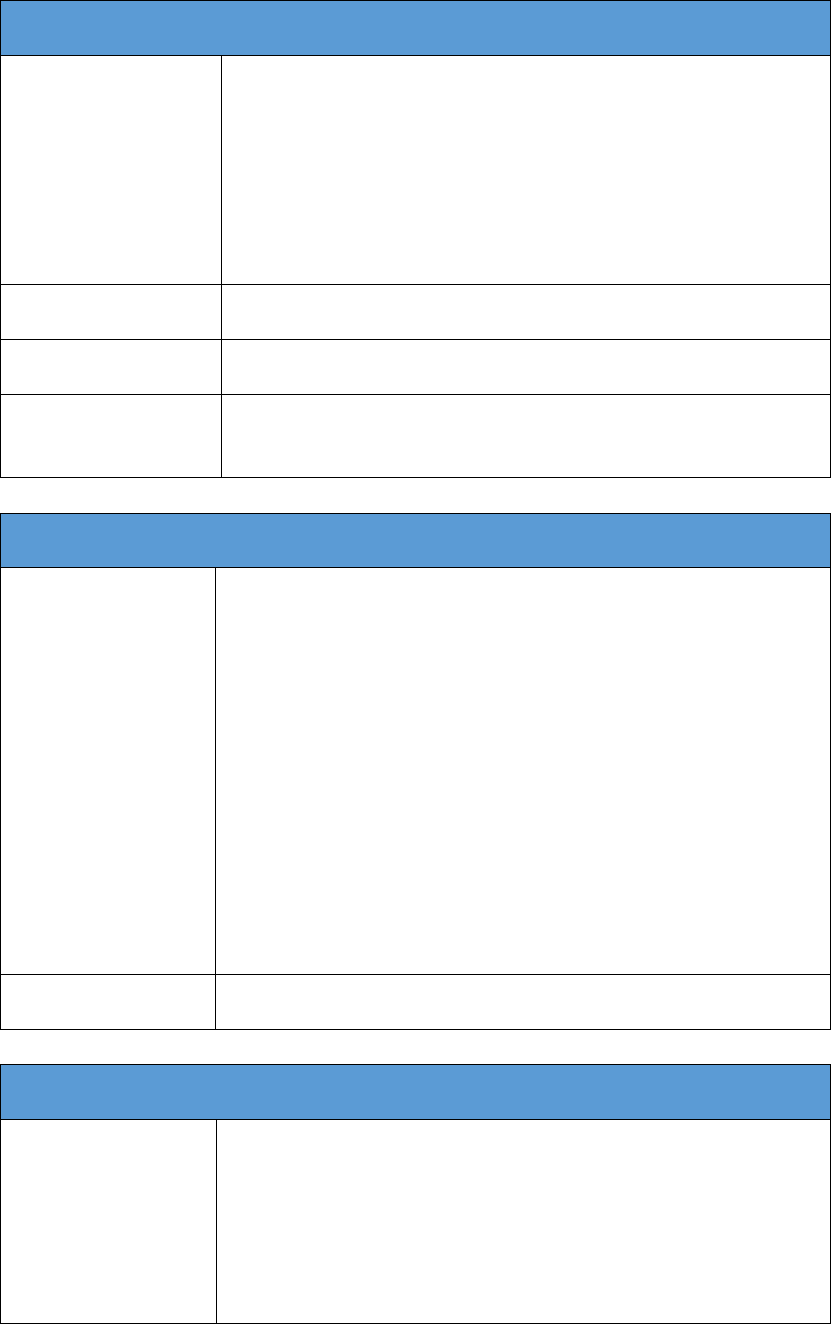

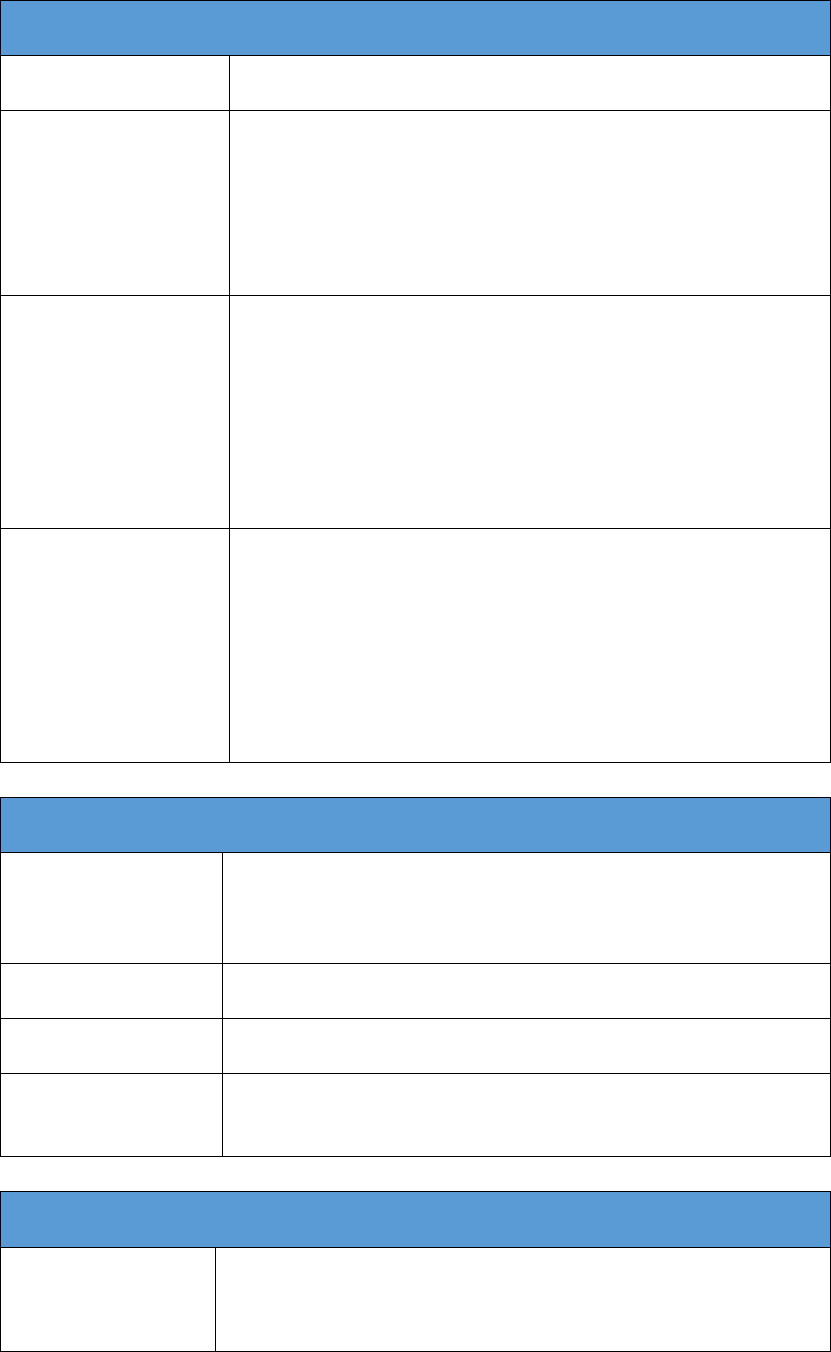

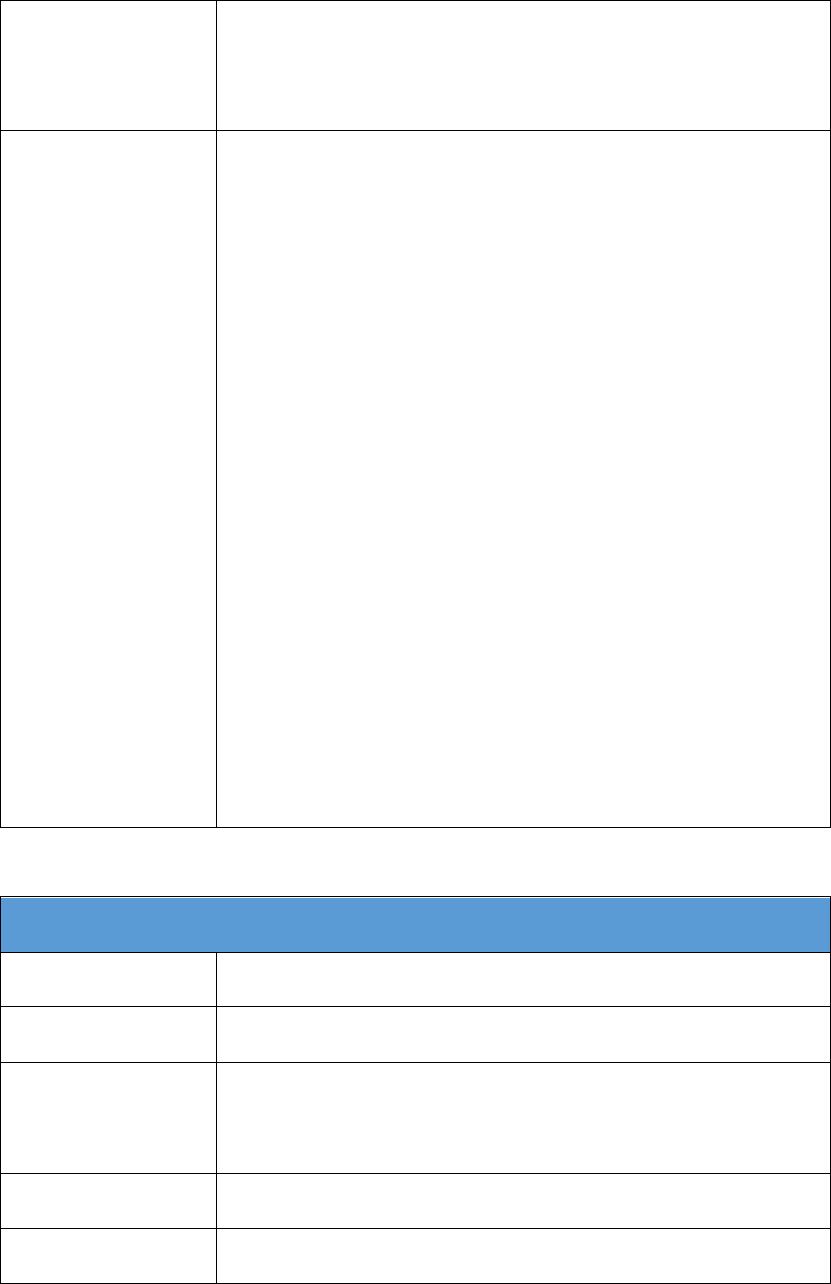

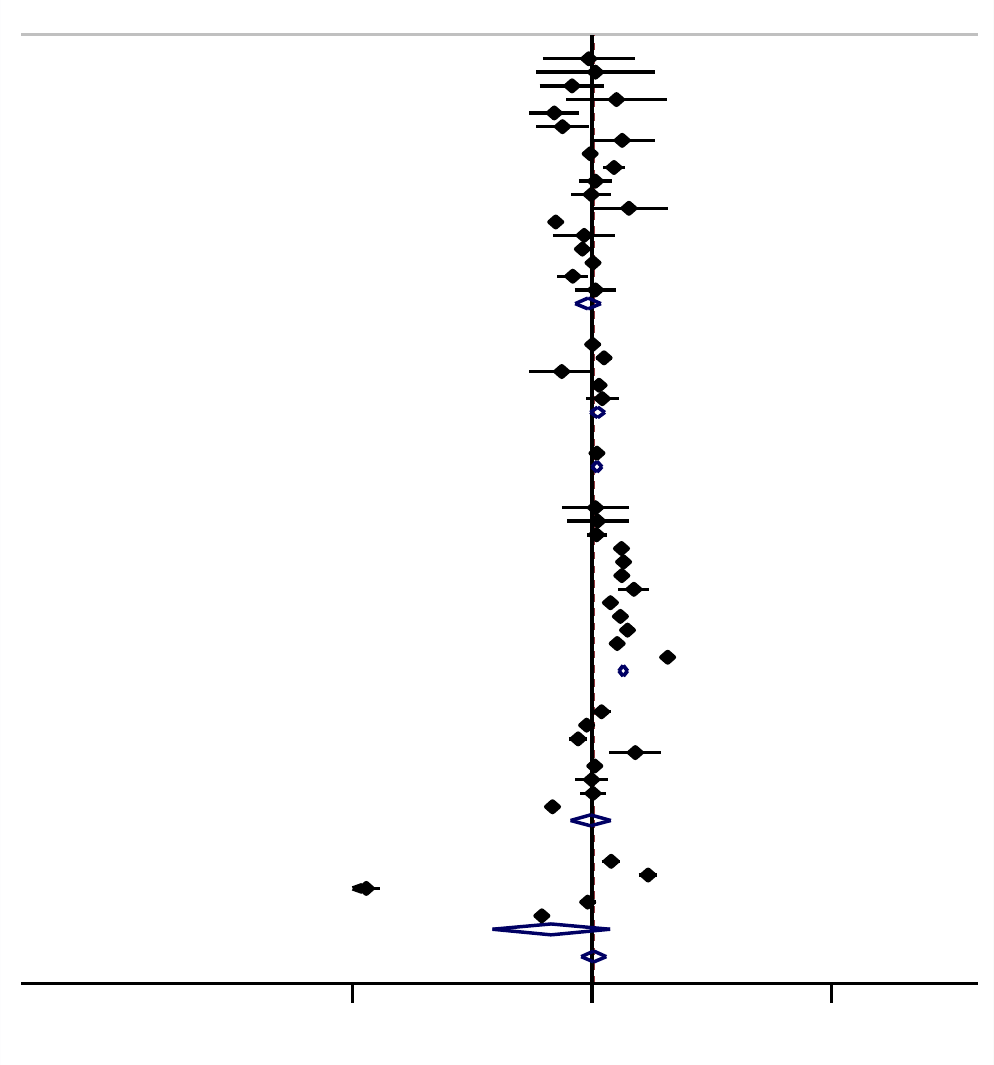

Figure 3, below, shows the meta-analysis results for the effectiveness of a bottom-up approach on

connectivity by type of settlement and extent of community participation. Improvement in connectivity

levels was seen neither in formal slums, nor in informal slums, when a bottom-up approaches was

deployed. However, in low-income non-slum settlements, use of a bottom-up approach led to a

10

significant decline in connectivity levels. A bottom-up approach becomes more effective only when

accompanied by community participation. Use of a bottom-up approach, along with community

participation, has led to a significant improvement in connectivity in informal slums, where there is no

security of tenure for the residents. This suggests that, when there are difficulties in creating tenure

security, a bottom-up approach, accompanied with community participation, are an appropriate

strategy to improve connectivity.

Narrative analysis shows that tenure security provides slum-dwellers the safety net to invest in

connectivity. Since informal slums are under the threat of eviction or demolition, slum-dwellers are

reluctant to invest in infrastructure improvements. Evidence from Jakarta, Indonesia, shows that

granting of tenure security to urban slums prompted slum-dwellers to invest in other housing

improvements, such as toilets, legal electricity connections, permanent roofs, and so on. Similar case

studies in slum improvement and slum up-grading in the cities of Dhaka, Mumbai, Ahmedabad (all

India), and Promeba and Rosario Habitat (Argentina), have included the importance of tenure security

in the programme implementation, along with access to new and improved facilities.

Legend

The numerical values show the aggregate quantitative measure obtained from meta-analysis.

Fig 3: Connectivity and bottom-up approach: by type of settlement and extent of

community participation

POLITICAL COMMITMENT

Political commitment, or a change in the government’s policy to adopt a pro-poor approach in delivery

of basic services to the urban poor, has had a positive impact on access in the top-down and a bottom-

up approach. This is mainly due to the removal of legal hurdles such as tenure security, which obviates

the need for slum-dwellers to provide proof of residence to seek new connections. A commitment from

Indicates improvement

Indicates decline

No change to status quo

11

the government in the form of universal access, pro-poor policy reform or a specific scheme to improve

access, provides a clear legal mandate to the public utility to extend coverage to poor consumers. It

may also include financial packages such as lower connection fees, which assist the poor in seeking legal

connections. The Depressed Area Electrification Program in Philippines, the accelerated electrification

program in Thailand and the Slum Electrification Program in Ahmedabad, are all examples of

government-led interventions that have improved access to electricity by bringing down connection

costs and granting tenure security.

The setting up of specialised agencies or cells that exclusively deal with the provision of basic services

in slums emerged as an enabling factor in improving access. Slums constitute a unique habitat that

comes with its own set of problems, which require inter-agency co-ordination and innovation in

operation, both of which may be stymied within existing institutional frameworks. In Brazil, two

electricity utilities, Rio LIGHT and Coelba, have set up community-based offices in their respective slum

areas in order to improve their outreach, payment collections and provide better customer service.

Similarly, the Bangalore Water Supply and Sanitation Board have created a social-development cell

within their office to focus exclusively on improving water connectivity to urban slums. Specialised

agencies or offices located within the slums facilitate closer interaction between the community and

the service provider, which, in turn, has a positive impact on access.

POLICY IMPLICATIONS

Political commitment should be backed by appropriate institutional arrangements for a top-

down approach to work.

Political commitment, combined with a networked approach and deeper understanding of

prevailing conditions (which include the setting up of specialised agencies created exclusively to

work with slums) have shown improvements in access. Overseas development assistance (ODA)

and other funding agencies that seek to generate political commitment should recommend the

setting-up of such dedicated organisations or specialised cells within existing organisations in order

to obtain better results in delivery of basic services.

A bottom-up approach is more effective in achieving an all-round improvement in access.

Access to basic services should not be seen as merely providing connectivity to taps, toilets or

electricity. A holistic approach to access helps to realise the benefits of improvements in access in

its entirety. A bottom-up approach lends itself very well to this scenario, as they have the necessary

elements to achieve improvements across multiple dimensions of access, due to beneficiary

participation, proximity of the service provider to slum-dwellers, sensitivity to community needs,

flexible payment options, consumer education, and community empowerment through training.

As policy shifts from community to personal household facilities, a bottom-up approach will have

a greater relevance.

The desire among policymakers is to provide individual connections to slum residents, rather than

public connectivity. However, individual connections need more involvement from the household,

both in terms of effort and investment. Enlisting the support of alternative service providers or

adopting a bottom-up approach can foster a sense of commitment through community interaction

and behavioural change. NGOs and CBOs can also provide the necessary technical and financial

support in the form of loans to obtain individual, household-level connections.

Addressing tenure-security issues plays an important role in effecting access.

Tenure security is critical to the provision of basic services in slum settlements. In order to

overcome the problems of tenure security, governments must accept their duty to provide access

12

to basic services in slums by: (i) removing land tenure as a prerequisite to seeking new connections;

(ii) amending the legal framework of government agencies to include informal settlements or

provide universal access; and (iii) use NGOs and CBOs as a medium to service informal slums by

engaging them in decentralised service delivery.

Programmes that aim to improve basic services should incorporate components of inclusivity

right from the project-conception stage.

Inclusivity and community participation are practices that need to be built into the project right

from the conception stage, in order to identify: (i) community needs and priorities; (ii) existing

resources and constraints; (iii) ways to mobilise community support; and (iv) prolonged

maintenance, as well as upkeep of the infrastructure, all of which are important for successful

service delivery in slums. The strengths and limitations of each of the stakeholders involved must

be studied and understood at the stage of drafting the project document, and avenues for

community members to participate/contribute their ideas at various stages of the project must be

institutionalised.

RESEARCH GAPS

The strength of the review depends on the evidence base. The evidence base for this review lacks

studies using experimental designs, in controlled environments. Primary studies deploying such

research-design methodologies would help in furthering our understanding of the causal pathway

between intervention and outcomes. For example, it could provide a clearer view of how involvement

of alternative service providers helps to improve community participation, and how community

participation leads to better outcomes. Overall, there is a need for studies with a higher degree of rigour

in research design than found at present, to better inform policymaking.

Future work could involve in-depth, region-specific studies, to get a clear understanding of contextual

factors that prevail in different regions. A specific region of interest would be Africa, where neither of

the two approaches has made a significant impact.

13

CONTENTS

SUMMARY

1: BACKGROUND

2: METHODS USED IN THE REVIEW

3: IDENTIFYING AND DESCRIBING STUDIES: RESULTS

4: IN-DEPTH REVIEW: RESULTS

5: SUMMARY AND IMPLICATIONS

6. REFERENCES

APPENDIX 1: REPORT AUTHORSHIP

APPENDIX 2: METHODS USED IN THE REVIEW

APPENDIX 3: IDENTIFYING AND DESCRIBING STUDIES

APPENDIX 4: META-ANALYSIS RESULTS

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS

14

1: BACKGROUND

1.1 BACKGROUND AND AIM OF THE REVIEW

The explosion of urban populations is a prominent

phenomenon observed in a large majority of

developing countries. There are numerous research

papers and policy documents highlighting the changing

urban dynamics in developing countries and the

implications for the policymaking processes of entire

countries. The United Nations Population Fund, which

published a report titled, State of World Population

2007 — Unleashing the Potential of Urban Growth,

mentions that, ‘While the world’s urban population

grew very rapidly (from 220m to 2.8bn) over the 20th

century, the next few decades will see an unprecedented scale of urban growth in the developing

world.....By 2030, the towns and cities of the developing world will make up 80% of urban humanity’

(UNFPA 2007). This report also predicts that Asia and Africa will account for the largest portion of the

global urban population.

This rapid urbanization has resulted in many benefits, such as economies of scale and agglomeration

making urban areas attractive investment destinations, wider and more diverse employment

opportunities, a blurring of social and cultural traditions, etc. However, there have also been several

unintended consequences of this urbanization process, such as overcrowding and congestion, increases

in crime and violence, growing inequality, absence of social and community unity, and a greater

incidence of urban poverty. In recent years, urban poverty has emerged as one of the biggest challenges

for national and sub-national governments. The challenge is further compounded because of the

multiple definitions and perceptions, across countries, of what constitutes ‘urban poverty’.

Urban poverty has been described by the World Bank as a multi-dimensional phenomenon, bringing

challenges such as 1) limited access to employment opportunities, 2) inadequate and insecure housing

and services, 3) violent and unhealthy environments, 4) little or no social-protection mechanisms, and

5) limited access to adequate health and education opportunities. Ravallion et al. (2007) analyse data

for 90 LIMCs. They find that an estimated one-third of all urban residents are poor and this figure

accounts for one-quarter of the world's total poor. Baker and Lall (2003) indicate that the incidence of

poverty is higher in small cities and towns than in large cities.

The urban poor face various challenges in their day-to-day life. Baker (2008) lists the following issues

as the most commonly mentioned/discussed in the literature: 1) limited access to income and

employment, 2) inadequate and insecure living conditions, 3) poor infrastructure and services, 4)

vulnerability to risks such as natural disasters, environmental hazards and health risks, 5) spatial issues

that inhibit mobility and transport, and 6) inequality, closely linked to problems of exclusion. The

prominent reasons behind these are: (i) a mismatch between official Master Planning and settlements

of mostly poor groups, designated as ‘slums’; and (ii) lack of availability of ‘infrastructure and services’

in these slums.

“If cities do not begin to

deal more constructively

with poverty, poverty

may begin to deal more

destructively with cities.”

- Robert McNamara, former President,

World Bank

15

The UN-HABITAT has analysed the urbanization phenomenon across the world and the report on the

state of the world's cities 2009/10 has presented the global assessment of slums. The report states that

828m, or 33% of the urban population of developing countries, resides in slums. This large proportion

of slum-dwellers has brought an intense focus on the ‘eradication of slums’ among leaders of both

developed and developing countries. The criticality of eradication of slums is recognised by the United

Nations under MDG 7, Target 11. The target is: ‘By 2020, to have achieved a significant improvement

in the lives of at least 100m slum-dwellers’ (MacPherson 2013).

As with the terms ‘urban’ and ‘poor’, ‘slum’ is defined and discussed from various perspectives. The

definition of ‘slum household’ by the UN-HABITAT broadly captures the concept discussed in the

literature, which is, ‘A slum household is a household that lacks any one of the following five elements:

1) access to improved water (access to a sufficient amount of water for family use, at an affordable

price, available to household members without being subject to extreme effort) 2) access to improved

sanitation (access to an excreta-disposal system, either in the form of a private toilet or a public toilet

shared with a reasonable number of people), 3) security of tenure (evidence of documentation to prove

secure tenure status or de facto or perceived protection from evictions), 4) durability of housing

(permanent and adequate structure in a non-hazardous location), and 5) sufficient living area (not more

than two people sharing the same room).’ There is also literature that links ‘slums’ to the legal status

of land — the non-recognition of tenure security to the dwellers.

The lack of physical infrastructure such as water supply, sanitation, waste collection, electricity, and

street lighting severely affects the health, quality of life and social well-being of slum-dwellers. The

impact of poor supporting infrastructure on the health of the urban poor has been investigated by

different agencies. The diseases common or prevalent in urban areas due to poor infrastructure are

diarrhoea, malaria, cholera and respiratory diseases.

Various policy interventions, such as slum up-grading, slum rehabilitation and resettlement, and so on,

are being adopted in various countries to improve housing conditions and delivery of urban services in

slums. The results of these interventions have been varied and there is a need to investigate the

evidence in order to understand the efficacy of various interventions and, based on these observations,

to design appropriate interventions for a particular situation.

1.2 DEFINITIONAL AND CONCEPTUAL ISSUES

SECTORS

This systematic review examines the evidence on the access to basic services in low-income or informal

settlements, under top-down and bottom-up approaches. Basic services generally include access to

water, sanitation, and energy. Energy comprises different sources, such as cooking fuel (kerosene,

cooking gas, etc.); electricity for heating, lighting, and operating lifestyle equipment; fuel for

transportation, etc. In the interest of keeping the systematic review focused, we considered only

electricity, and excluded all other forms of energy. In addition, the decision to focus on electricity was

also driven by the literature. Studies that have analysed energy services for the poor have invariably

focused on electrification (for example, Baruah 2010). Moreover, access to electricity provides a wide

range of economic, social and health benefits (Price 2000; World Energy Assessment 2000). The

benefits from access to electricity have been well identified with the achievement of the MDGs (Flavin

and Aeck 2006, Ha and Porcaro 2005).

16

COUNTRIES

This review will focus on evidence from LMICs, together referred to as ‘developing countries’ by the

World Bank

1

. The study was restricted to developing countries because of the substantial heterogeneity

in context between developed and developing countries, which can limit the validity of the synthesis.

While it is recognised that there is considerable heterogeneity even among developing countries, we

chose not to limit the countries to be included in the review because of the widespread problems of

slums and low-income informal settlements seen in these countries. For example the percentage of

urban populations living in slums in 2001 in developing countries was 43%, whereas the corresponding

percentage for developed countries was only 6% (UN-HABITAT 2003). Therefore, the topic of this

review is very relevant for a majority of the developing countries, and our strategy is to capture the

diversity by contextualising the analysis or incorporating the same as appropriate moderator variables

in statistical synthesis.

INTERVENTIONS

The interventions for this review can be broadly classified into two categories: the traditional top-down

approach (by centralised planning and implementation by the government – and sometimes private –

provision of services) and the bottom-up approach (by alternative service providers, such as NGOs and

CBOs). Categorising in this way also gives an indication of the degree of inclusivity, the bottom-up

approach being more inclusive than the top-down approach. Inclusive urban planning, for example,

takes into account the needs of the poor and formulates specific strategies to improve or redevelop

slums in ways that make the poor better off. In general, a top-down approach is less inclusive than a

bottom-up approach. If the framework is formal city-level planning, driven by the government, then it

constitutes a top-down approach. In contrast, if the approach is for micro-planning for individual slum

improvements, then it would be classified as a bottom-up approach. In between these two extremes,

there is a spectrum of approaches that involve varying levels of inclusivity. For example, the

involvement of NGOs, CBOs, and resident associations increases the element of inclusiveness in the

planning and implementation process.

In general, in the absence of clear information, we take government to be the default service provider.

Service providers that involve other providers are classified as alternative service providers. For

example, if there is no information on involvement of any alternative service provider, it is assumed

that the service provider in the slum was the government. If the services in the slum are provided by

non-government or private service providers, the slums are categorised as being serviced by alternative

service providers.

We considered the level of participation from the community as accounting for the degree of inclusivity.

Participation refers to the involvement of different stakeholders, such as community residents, officials

from government, and other institutions, such as NGOs and CBOs, in the delivery of basic services.

Possible forms of community participation are as follows (adapted from UN-HABITAT 2003, Kingston

1998):

1

Source: http://data.worldbank.org/about/country-and-lending-groups accessed on 24 June, 2014;

http://data.worldbank.org/about/country-classifications

17

Passive participation: Poor communities participate by being told about initiatives that are being

planned or have already been decided upon, without any attempt to elicit local opinion or knowledge.

Participation through giving information: Poor communities are asked about their needs through

surveys or similar instruments. The information is used anonymously in the decision-making process,

without feedback.

Participation through consultation: Poor communities are consulted as to what should be done to

improve the situation, but there is no obligation to take the residents’ views into account.

Participation through contribution: Poor communities are asked to provide labour or financial

contributions towards the provision of services and the residents agree to take primary responsibility

for the well-defined components of the project.

Participation through partnership: Poor communities and other key actors share resources, knowledge,

and risks in pursuit of commonly agreed-upon improvements. Partnership implies a long-term,

equitable relationship.

Participation through self-mobilisation: Poor communities work together to demand and/or implement

improvements in basic services. They develop contacts with experts, who will contribute with

managerial and technical skills, but community groups retain control over how the resources are used.

Since many studies do not give details of the level of participation, we broadly classified participation

into two levels: with and without participation. Passive participation was classified as ‘without

participation’ and the remaining five levels of participation were classified as ‘with participation’.

However, when summarising the studies numerically for the bottom-up approach, ‘with participation’

was further classified into two sub-categories to denote the extent of participation. Participating by

giving information, consultation and contribution were grouped into one sub-category, whereas

participating through partnership and self-mobilisation were grouped into a second sub-category.

We differentiate between inclusivity and participation because an inclusive urban-planning approach

may or may not be participatory. (Examples include the Basic Services for Urban Poor (BSUP)

programme implemented by the government of India). Similarly, high levels of participation do not

guarantee a higher degree of inclusivity. For this reason, these two dimensions were captured

separately when characterising the nature of the planning framework.

MODERATORS

The outcomes are dependent not only on the interventions, but on a lot of other variables. Together,

we refer to them as moderator variables. To facilitate analysis of these moderators, they were broadly

classified into one of three categories: context, content, and process (adapted from Pettigrew 1987,

Dawson 1994, and Nelson and Dowling 1998). Context refers to the wider social environment and the

individual setting of the slums. Content refers to the elements of the intervention. Process refers to the

actions, reactions and interactions of the various interested parties in the implementation of the

programmes/planning framework.

Based on the literature reviewed and the inputs from the advisory board, we classified the moderators

into the following categories:

18

Context: Type of slum (declared or undeclared slum); security of land tenure; and institutional form and

structure; spatial location of the slum, etc.

Content: Type of facility (for example, in the case of water supply, is it a household connection to piped

water, a connection to a public water outlet, or access to non-piped water, such as open or bore wells);

source and quantum of funding for the project.

Process: This includes implementation, maintenance and operations of the facility.

OUTCOMES

This review synthesises the evidence on top-down and bottom-up approaches in improving access to

basic services for the urban poor. Access is an important element in achieving the MDGs (Global Urban

Observatory 2003) and is the outcome under consideration in this review. In this review, we consider

access to have the following dimensions or outcomes: connectivity, affordability, adequacy, effort and

time, durability and sustainability. Assessments of effect (positive, negative, etc.) on the above

outcomes arising from the different delivery approaches have been synthesised in this review. While

the traditional definitions of access would mean connectivity to the service, it has been indicated that,

in the context of improvement of slums, the indicators of access would be more broad-based. The

different access indicators for the three sectors (UN-HABITAT 2002) are:

Water supply: Proportion (or number) of households with access to water supply, availability at an

affordable cost; at a sufficient quantity; and without excessive effort and time.

Sanitation: Proportion (or number) of households with access to adequate sanitation facilities.

Electricity: Proportion (or number) of households with electricity connections; availability of electricity

at an affordable cost; at specified voltages; and without excessive disruptions.

Based on the above, we define the different dimensions of access as follows:

Connectivity: This dimension seeks to study the proportion (or mean number) of households with

access to services such as water supply (public tap or individual in-house tap), sanitation facilities

(individual toilet or community toilet) or legal electricity connections at household level, provided

either by government or alternate channels.

Affordability: The proportion of households who found the services affordable (or) the mean cost

involved in accessing the services for the dwellers.

Adequacy: This dimension seeks to measure the proportion of households who found the services

adequate (or) the mean level of consumption of services.

Effort and time: Proportion of households who were able to access the services without excessive effort

and time (or) the distance from the households for accessing the services (mainly relevant for water

and sanitation) will be studied under this dimension.

Durability: This seeks to explore whether the improvements in access is temporary or of a more

permanent nature. While the definition of what is temporary or permanent is subjective and can differ

between contexts, our objective is to check whether the improvements are short-term or likely to be

long-term.

19

Sustainability: This dimension would analyse the environmental impact of the facilities created to

provide access.

In sum, our outcome indicators consist of the following components of access: connectivity,

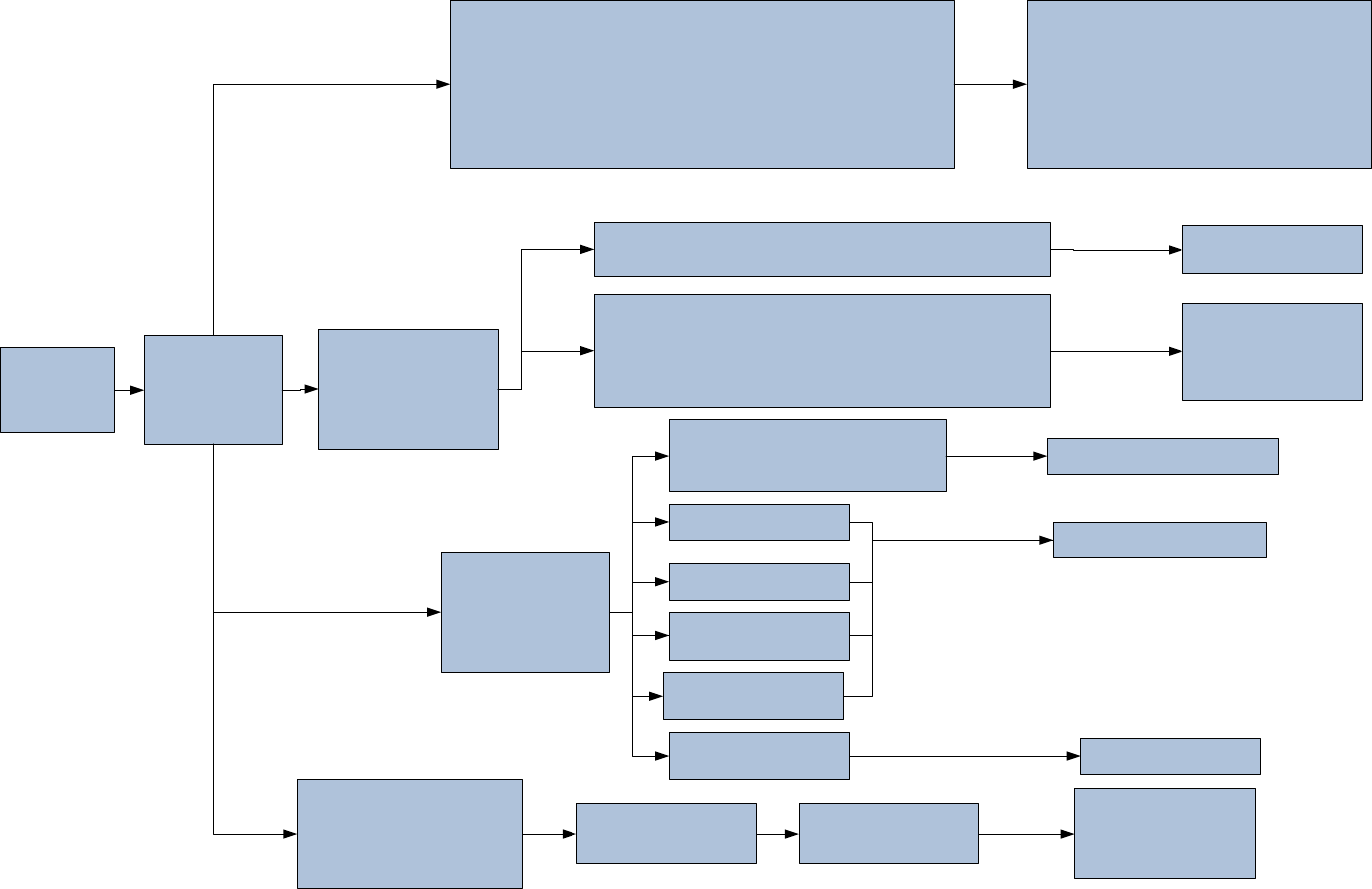

affordability, adequacy, effort and time, durability and sustainability. Figure 1.1, below, gives the

conceptual overview of the review.

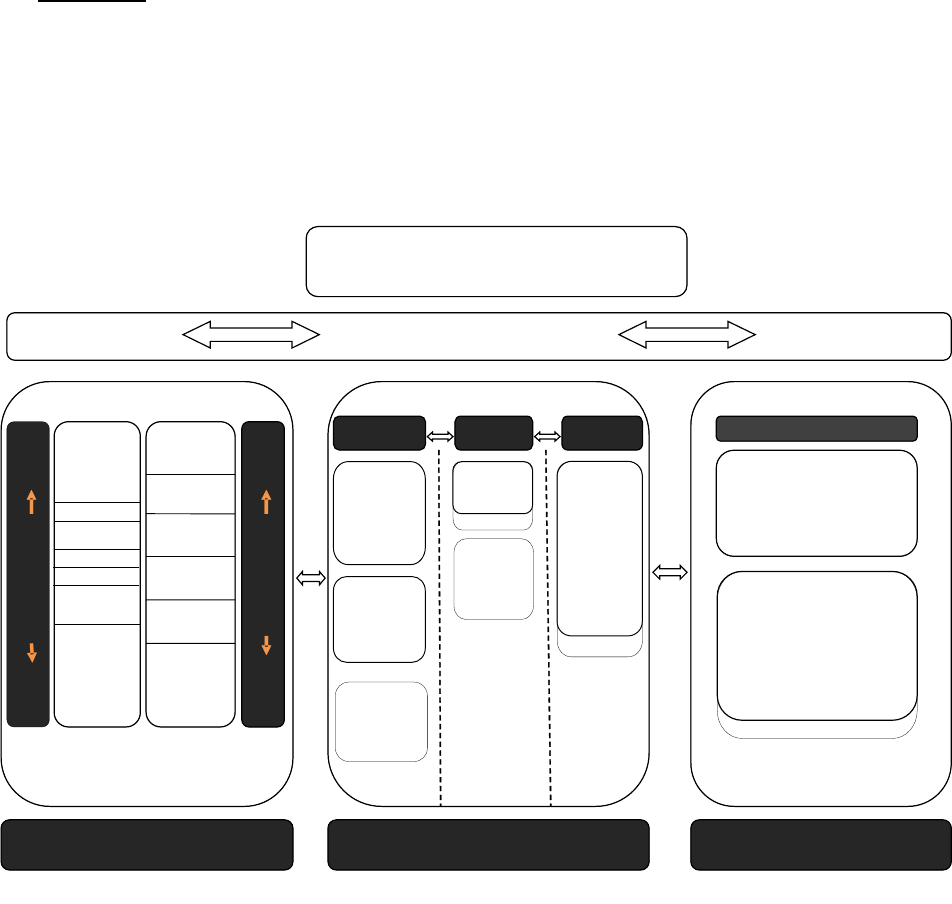

Figure 1.1: Conceptual overview of the review

?

??

+

??

?

??

Top-down

approach

-

City-level

plan

Government

Grant

agencies

NGOs

CBO

s

User

involvement

Bottom

-

up

approach

Micro-slum

development

program

s

Access

to s

ervices

Sectors

Water

supply

Sanitation

Electricity

Components of access

Connectivity

Affordability

Adequacy

Effort and time

Durability

Sustainability

Context

Content

Process

Type of

settlement

Notified

Informal

Institutional

form and

structure

Slum

features

(land

tenure,

location, etc.)

Type of

facility

Type and

q

uantum

of

funding

Implementati

on,

maintenance

and

operations

State

Community

Private

Dwellers

Interventions

Moderator

s

Outcomes

Passive

Participation

Information

Consultation

Contribution

Partnership

Self

-

mobilization

Planning

Implementation

D

elivery

Access to

basic

s

ervice

s

in slums and low

-

income

informal

settlements in urban areas

High Part icipative spectr um Low

Hi

gh

Granularity of Pla nning

Low

20

1.3 POLICY AND RESEARCH BACKGROUND

The global urban population is growing, with 54% living in urban areas in 2011, and this is expected to

increase to 66% by 2050 (Heilig 2012). According to a 2008 study by UN-HABITAT, one-third of the urban

population in developing countries at this time lived in slums, the conditions being noticeably worse in

some regions than others. For instance, in Sub-Saharan Africa, 62% of the urban population resided in

slum areas (UN-HABITAT, 2013). These are low-income or informal settlements where housing and

living conditions are very poor. They are often characterised by lack of access to basic services and

infrastructure, such as roads, street-lighting, drinking water and sanitation, due to a lack of legal

recognition. Households in these areas end up paying many times more than the public-network fee

charged for poor-quality water and sanitation services, since they are not served by the formal services.

Inadequate access to safe water and sanitation are responsible for a high burden of communicable

disease in developing countries, especially diarrhoeal diseases (Prüss et Al. 2002). Children under the

age of five bear the highest burden in this regard, with diarrhoea being one of the leading causes of

child mortality (contributing to 11% of all child deaths in 2010) (UNICEF 2012). Treating these diseases

also incurs high economic costs: that is, direct costs, including expenditure on healthcare for treating

illnesses, and indirect costs, such as loss of productive labour time due to sickness and caregiving. Other

costs include effort and time spent on fetching water, indignities faced due to open defecation, lack of

safety, and so on — factors especially affecting girls and women. The total economic costs of lack of

access to water and sanitation has been estimated at US$260bn per year (Hutton and Haller, 2004).

Investment of US$1 in this sector is estimated to have a global economic return of US$5 (on average)

through time saved, reductions in morbidity and mortality rates and improvements in productivity. For

instance, Ghana’s Trachoma Control Programme reduced the prevalence of active trachoma from 9.7‒

16.1%, to less than 3% in endemic districts between 2000 and 2010 through interventions such as water

and school-latrine provision, sanitation promotion using the community-led Total Sanitation approach,

and hygiene promotion (WaterAid 2014). Globally, time savings associated with improved sanitation

were estimated to be 30 minutes per individual per day, and 30 minutes per household per day for

improved water supply.

With growing urban populations and the increasing urbanisation of poverty, provision of water and

sanitation services to low-income and informal settlements in urban areas is a serious challenge faced

by the governments of developing countries.

MDGS AND ACCESS TO WATER AND SANITATION

The MDG for sustainable development adopted international targets for provision of water and

sanitation services and improvement of slum conditions. The incorporation of these targets into MDGs

underscores the policy relevance accorded to this sector. The goals, targets, indicators and progress

achieved to date are explained below (United Nations 2013):

MDG 7: Ensure sustainable development

Under this goal, the relevant targets are listed below:

MDG Target 7.C: By 2015, reduce by 50% the proportion of the population without sustainable access

to safe drinking water and basic sanitation.

21

Indicators:

1) Proportion of population using an improved drinking-water source.

2) Proportion of population using an improved sanitation facility.

Progress: In 2012, the proportion of the world’s population with access to an improved drinking-water

source was 89%, up from 76% in 1990. Although the target of halving the proportion of people without

access to an improved source had already been achieved in 2010, there were 748m people still lacking

access to safe drinking-water sources in 2012. Also, between 1990 and 2012, almost 2bn people gained

access to an improved sanitation facility (one that separates people from faeces hygienically). Despite

the large increases in sanitation coverage, however, 2.5bn people still did not have access to an

improved sanitation facility in 2012, out of which 1bn people resorted to open defecation.

MDG TARGET 7.D: By 2020, to have achieved a significant improvement in the lives of at least 100m

slum-dwellers

Indicator: Proportion of urban population living in slum-like conditions.

Progress: Although this target was achieved long before its deadline, the number of slum-dwellers

continues to grow. The number of urban residents living in slum conditions (lack of access to water, lack

of access to sanitation, overcrowding, dwellings made of non-durable material) was estimated at 863m

in 2012, up from 760m in 2000, and 650m in 1990.

PROVISION OF WATER AND SANITATION

NATIONAL AND REGIONAL GOVERNMENTS

National and regional governments, historically, through taxes redistributed through the public-sector

budget budgeting, have accounted for the majority of the spending in the water and sanitation sector.

Following the adoption of MDGs across the world, governments have increased commitments to the

water and sanitation sector in order to achieve the MDG targets. In 2008, African Union Governments

signed the Sharm el-Sheikh declaration, committing to prioritise water and sanitation and improve

transparency and accountability. In the eThekwini declaration, African ministers committed to

allocate at least 0.5% of gross domestic product (GDP) to fund sanitation and create separate public

budget lines for sanitation and hygiene in their countries (WaterAid 2011). Similarly, in the third High

Level Meeting of Water and Sanitation for All, convened by UNICEF, ministers from 43 developing

countries made commitments relating to steps that will be taken to remove constraints on the

expansion of water and sanitation services (SWA 2014). In recent times, governments have also tried

innovative approaches to increase access to the poor, instead of the traditional one-size-fits-all

model, as seen in, for example, the provision of conventional pipe networks.

Often in the past, national governments planned investments in water and sanitation through

local/regional governments and public-private partnerships, which, in turn, did not adequately address

the needs of the poor (Belsky et al. 2013). However, in recent times, slum upgrading (provision of

housing and basic services) has been increasingly recognised as a strategy for improving the conditions

of the urban poor and catalysing private investments by residents (Cities Alliance 2006). Country and

city development strategies are becoming more inclusive (inclusive urban-planning approaches), by

22

taking into account, within their frameworks, the provision of basic services for the urban poor. For

instance, the government of India’s Jawaharlal Nehru National Urban Renewal Mission (JNNURM),

targeting 63 key cities and urban areas, focuses on services to the poor as one of its explicit missions.

Under JNNURM, it is mandatory for all local bodies to implement the following poverty reforms in order

to receive funding: local urban bodies should allocate funds to provide basic services to poor

households within local budgets; provision of these services to be implemented within a specific time

period, earmarking at least 20‒25% of developed land to low-income categories; and so on. When the

cities implement these reforms, it is expected that slum-dwellers will gain access to basic municipal

services, such as water supply, toilets, waste-water drainage, solid-waste management, power, roads,

and transport (CGG 2010).

OVERSEAS AID

Multilateral agencies such as the World Bank, the WHO and UNICEF, bilateral donors such as USAID,

DFID and the Swedish Development Cooperation Agency (SIDA), national and regional governments,

international and local NGOs have been engaged in improving access to water and sanitation services,

particularly to poor people across the world. The World Bank group is the largest source of external

financing for water-related interventions. During 2009‒13, financing to the tune of US$16.9bn was

approved for water- and sanitation-related projects supported by the bank. It is estimated that bank-

supported projects have provided 123m and 5.8m people with improved access to, respectively, water

and sanitation between 2002 and 2012 (World Bank 2014).

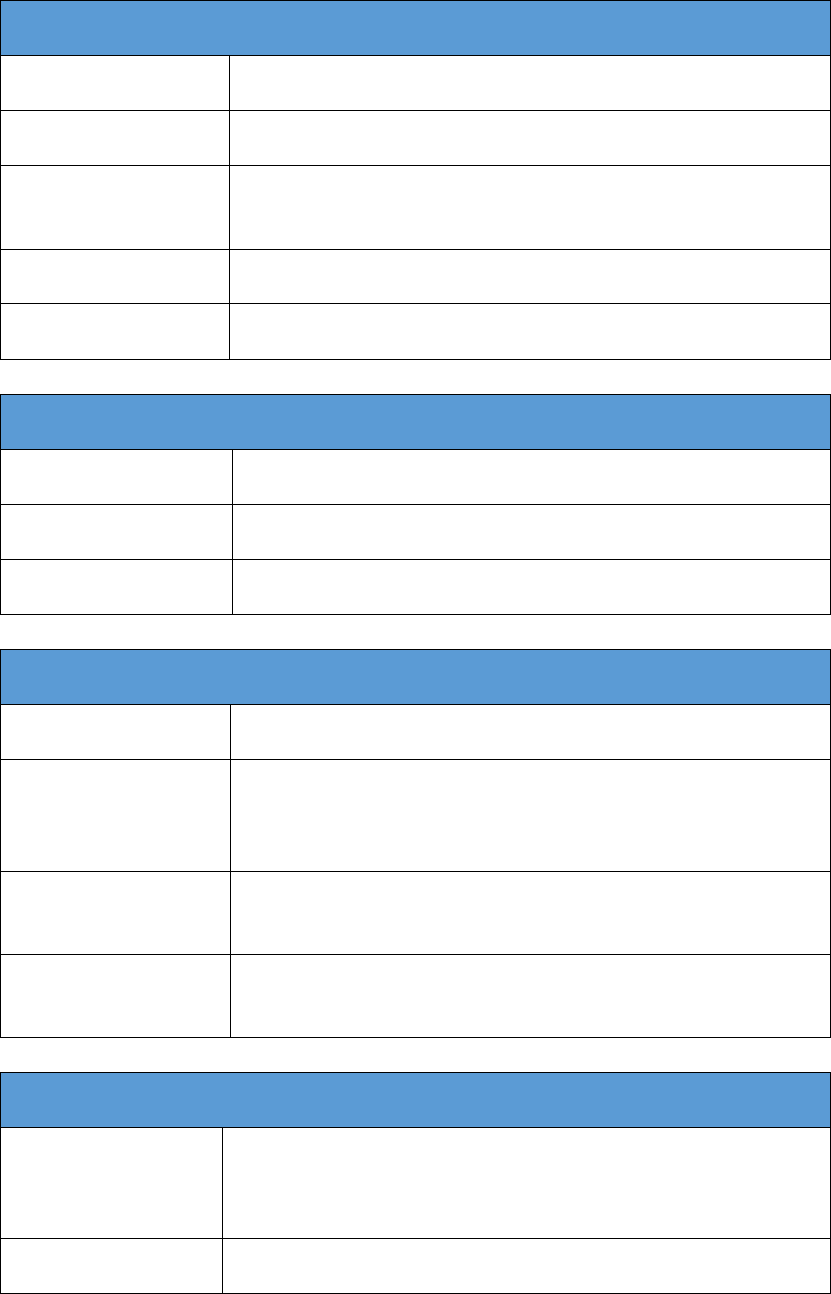

Following the adoption of water and sanitation targets in the MDGs, ODA commitments to this sector

have also increased. ODA to developing countries for the water and sanitation sector increased to over

five times 1990 levels (see Figure 1.2). ODA to the water-supply and sanitation sector amounted to

more than US$7.6bn in 2010‒11 (total annual aid commitments), representing 6% of total sector

allocable aid. This is targeted to regions that have poor coverage of water and sanitation services: Sub-

Saharan Africa received 25% of total aid and South and Central Asia 23% in 2010‒11. The poorest

countries received 33% of total aid to the sector (OECD 2013). Of total aid, 19% was contributed to

water-supply activities, 18% to sanitation and 42% to combined water-supply and sanitation activities.

Figure 1.2: Official Development Assistance to Water Supply and Sanitation

0

2000

4000

6000

8000

10000

12000

1971

1973

1975

1977

1979

1981

1983

1985

1987

1989

1991

1993

1995

1997

1999

2001

2003

2005

2007

2009

2011

USD (millions) current prices

23

Source: Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development Creditor Reporting System

database.

2

ODA is primarily directed to bilateral and multilateral organisations. For instance, DFID expenditure on

water, sanitation and the hygiene sector amounted to €245m in 2010‒11, and was concentrated on

Asian and Sub-Saharan regions (DFID 2012). Similarly, AusAid supports water and sanitation projects in

the Indo-Pacific region through partnerships with governments, NGOs, civil societies and multilateral

partners such as the World Bank, with an estimated expenditure of US$163.5m (DFAT 2014).

INNOVATIVE PARTICIPATION BASED APPROACHES TO DELIVER BASIC SERVICES

In recent times, effective community participation to design and implement water and sanitation

projects for the urban poor has been attributed importance by the governments and overseas donors.

This is essential for making these projects more demand-driven and for ownership, use and

sustainability of these assets (OECD 2013). Also, traditionally, infrastructure projects rely more on tariffs

for cost recovery. As an alternative, Winpenny and Camadeus’ (2003) recommend finding an

appropriate combination of tariffs, taxes and transfers (the 3Ts; primarily through ODA) for each

country, in order to finance water and sanitation projects sustainably. The report also recommends

sustainable cost recovery, rather than full-cost recovery, and recommends setting tariffs policies that

are affordable to all sections of society, including the poorest.

Table 1.1, below, provides some examples of different successful approaches that have been

implemented in various regions of the world, to provide access to water and sanitation to the urban

poor; the text following it gives a short description of these approaches.

Table 1.1: Illustrative approaches for giving water and sanitation access to urban

poor

Type

Policy/Project

Name

Country

Sector

Approach

Description

NGO-

Communities

Orangi Pilot

Project (OPP)

(WSP 2009).

Pakistan

Sanitation

Bottom-up, with

community

participation

through

contribution.

Micro-slum sanitation

project, completely

financed and built by the

community, while an NGO

provided technical

assistance.

2

http://stats.oecd.org/qwids/ accessed on 15 July 2014.

24

Type

Policy/Project

Name

Country

Sector

Approach

Description

National and

regional

governments,

CBOs,

communities

Water and

Sanitation

Program for

Low-Income

Urban

Population

(PROSANEAR I)

(Katakuraand

Bakalian 1998).

Brazil

Water and

sanitation

Top-down

approach, with

participation

through

consultation.

PROSANEAR teams went

into communities to ask

which kind of project the

community preferred, and

if they were willing to

contribute effort, time and

money to the project.

City

development

plan/strategy

Ger-area

(Informal

settlements)

Upgrading

Strategy (GUS)

(Cities Alliance

2010).

Mongol-

ia

Water and

sanitation

Top-down

approach, with

community

participation

through

consultation/

giving.

Municipality of

Ulaanbaatar city, capital of

Mongolia, developed city-

wide pro-poor Ger-area

(informal settlements)

upgrading strategy, in

consultation with various

stakeholders.

ODA, NGOs,

CBOs, local

governments

Community-led

Infrastructure

Facility (CLIFF)

(Jack and Morris

2005).

India,

Kenya

Housing,

sanitation

Grant-based

approach.

CLIFF helps in leveraging

the financial resources of

slum-dwellers, so that they

can access capital from the

public and private sectors.

Orangi is Karachi’s largest informal settlement, with a population of more than 1m, and has faced a

huge sanitation and sewerage crisis. In this scenario, OPP (set up by the Bank of Commerce and Credit

International Foundation, with the social scientist, Dr Akhtar Khan) developed a low-cost sanitation

technology and convinced the residents of lack of funds with the local bodies to construct sewer system

for the community. They provided technical guidance to enable poor households to construct and

maintain their own sanitation systems. The residents were, in turn, responsible for the finances and

management of the construction work. In this way, improved sanitation was provided for

approximately 900,000 people and 94,122 houses, at the cost of only US$13 per household. This is an

example of a micro-slum project planned and implemented by an NGO and the local community.

PROSANEAR I is not a single project, but a group of different projects implemented in various

communities across different districts of Brazil. The project was jointly financed by the World Bank

(50%), the local water companies, state or municipal government (25%), and the Caixa Econômica

25

Federal (CEF, the Brazilian Government development bank (25%).

3

PROSANEAR I mandated low-cost

technology (investment ceilings were fixed at US$98 and US$140 for water and sewerage, respectively)

and community participation, through which it brought water and sewerage connections to 1m people

in low-income settlements across 17 cities. This is an example of a top-down approach with community

participation through consultation.

GUS is a citywide development strategy involving participation through consultation/giving for

upgrading the Ger areas

4

of Ulaanbaatar city. The city was supported with services like water supply

and electricity network, but Ger areas enjoyed limited access to these services due to a lack of legal

recognition and planning for upgrading, among other factors. GUS was then developed through

consultation with multiple stakeholders, including government agencies, the private sector, civil

societies, NGOs, Ger communities and international aid agencies. Accordingly, Ger areas were classified

into three types (Central, Middle and peri-urban areas), and specific strategies for upgrading were

developed. Since the adoption of these strategies in 2007, the design and implementation of national

and international programmes and projects for the upgrading and development of Ger areas are guided

by these strategies.

CLIFF in India was established by Homeless International, with funding from DFID and SIDA. CLIFF

provides loans and technical-assistance and knowledge grants, and guarantees to the community-led

slum-upgrading schemes that are taken up in partnership with city authorities. CLIFF kick-starts

community projects, initially with loans, while negotiations for funding from other sources, such as

banks, takes place. These resources are used for sustainable housing and basic services’ projects for

slum-dwellers (including sanitation), with potential for scaling-up. During Phase I (2002‒10), 29 projects

were taken up, of which sanitation was a component of four. This programme has now been expanded

to Kenya and Philippines (EUWI and SHARE 2012).

There are other examples of water and sanitation projects implemented for improving access to urban

poor through different partnerships. Although there have been various kinds of interventions to

improve access, there is little evidence as to which approaches are most effective and efficient in

delivering basic services to the urban poor. In a report on the bilateral aid review of the Water,

Sanitation and Hygiene (WASH) portfolio, DFID notes that ‘There is limited rigorous evidence regarding

the best choice of context-specific delivery models for programming.‘ (DFID 2012). The report attributes

two reasons for this: a lack of systematic data for evaluating the effectiveness of specific interventions,

and huge variations between approaches implemented across different settings. While lack of data and

variations in the context cannot be easily overcome, this review is an attempt to synthesise the

evidence through a systematic search of the literature.

SUMMARY

For project planners, policymakers and service providers, there is a pressing need to understand the

context-specific factors responsible for success or failure of different approaches to delivering basic

services to the urban poor, experimented with across different regions of the world. This will help to

3

The World Bank provided the loan to the CEF, which, in turn, loaned it, along with its contribution, to

the Municipality or other government agencies responsible for project implementation.

4

Ger areas are traditional low-density settlements that are not recognised as formal parts of the city.

26

identify barriers and propose practical solutions to improving access to basic services among the urban

poor. However, systematic reviews on water and sanitation interventions extensively focus on their

health-related effects, such as a reduction in diarrhoeal diseases (Fewtrell et al. 2005) in developing

countries and the nutritional status of children (Dangour 2013), while there is no such review on the

effectiveness of different approaches and their determinants. Consequently, a systematic review of

evidence on best urban planning practices to provide improved water and sanitation services to the

poor will help inform public policy and achieve further progress towards achieving MDGs.

1.4 AUTHORS, FUNDERS AND OTHER USERS OF THE REVIEW

The authors, funders and members of the study advisory board are given in Appendix 1. The study was

funded by DFID. The EPPI-Centre, Social Science Research Unit, Institute of Education, University of

London, provided the technology and advisory support for the review.

The results of this review will be particularly useful to multilateral and bilateral funding agencies, urban-

planning agencies, and governments and civil-society organizations.

1.5 REVIEW QUESTIONS

The review was initially conceptualised to synthesise the evidence on the effectiveness of different

urban-planning frameworks for improved access to water, sanitation and electricity services in low-

income or informal settlements. However, a review of the available evidence indicated that outcomes

cannot be attributed only to planning. The results are also dependent on the mode of implementation

and delivery of services. In addition, studies did not specifically analyse planning in isolation, but very

often treated planning-implementation-delivery as one continuous spectrum. Therefore, the review

synthesised the evidence on the entire delivery approach to provide basic services, and not just on

planning. This approach was supported by the study-policy advisory board as well, since efforts to

provide basic services were often not a part of city-level plans, but were bespoke, micro-level

implementations.

Secondly, studies indicated the prevalence of two polar-opposite approaches in the delivery of basic

services to slums — the first in which the effort was led by the government and the second in which

the effort was led by alternative service providers such as NGOs, CBOs, and the private sector. The

former was called the top-down approach and the latter was called the bottom-up approach. While it

may not be possible, in practice, to have a purely government-led implementation without any

involvement from the community, NGOs, CBOs, etc., or vice versa, the classification of a top-down or

bottom-up approach was based on who played the dominant role in the delivery of basic services. The

programme descriptions given in the studies was carefully reviewed when classifying as top-down or

bottom-up.

Given this context, the question that was taken up for this systematic review was:

‘What is the evidence on top-down and bottom-up approaches in improving access to water, sanitation,

and electricity services in low-income or informal settlements?’

More specifically, the objective of the review was to seek answers to the following:

1. How effective are the top-down and bottom-up approaches in improving access to water

supply, sanitation and electricity services in low-income or informal settlements in LMICs?

27

2. Under what circumstances do these approaches deliver better results? Why?

3. What are the strengths and limitations of these two approaches in respect of providing access

to basic services in low-income areas and informal settlements?

1.6 OUTLINE OF THE REPORT

The report is organised into five chapters. The current chapter introduces the report. Chapter 2

describes, in detail, the methodology adopted. Chapter 3 provides a description of the identified studies

using the methodology described in Chapter 2. Chapter 4 provides the results of the in-depth review of

the studies identified in Chapter 3. Chapter 5 highlights the key findings, implications and certain

limitations of the review.

28

2: METHODS USED IN THE REVIEW

2.1 OVERVIEW

This chapter provides the details of the search strategy, the methods used to identify the studies to be

included in the review, and the methods used to synthesise the results in the included studies. The

process comprises the following steps:

Formulating exclusion and inclusion criteria to be used to determine the studies to be included

in the review

Deciding on the sources and the search methods (search phrases) to be used to identify the

studies.

Managing the shortlisted and identified studies using a review-management software.

Synthesising the evidence in the included studies using the following methods: numerical

summary, meta-analysis and textual narration.

The entire search process was carefully documented and the number of studies identified was recorded

at each stage, so that the entire process can be replicated, if need be, by other research groups. In

addition, documenting the search process will also help in updating the review in the future to include

additional studies that might have been carried out. Documenting the search process and the use of

well-defined exclusion and inclusion criteria also helps to reduce the study selection bias that might

occur in non-systematic reviews.

2.2 USER INVOLVEMENT

APPROACH AND RATIONALE

Evidence-based policy making is emerging as a major imperative. In recent times, international funding

and development agencies have been increasingly using past evidence as one of the important

parameters in their funding and developmental-assistance decisions. The authors of this review clearly

understand this imperative and would, therefore, direct this review towards policymakers and

practitioners.

METHODS USED

The main users of this review will be policymakers, as well as funding and development agencies such