A Minimum

Pay Rate for

App-Based

Restaurant

Delivery

Workers

in NYC

© November 2022. New York City Department of Consumer and Worker Protection. All rights reserved.

i

Acknowledgments

The Department of Consumer and Worker Protection (the Department) acknowledges the following staff who

contributed to this report: Marlee Belford, Matt Bondy, John De Vito, Anastasia Eriksson, Maria Jennings, Sam

Krinsky, Elizabeth Major, Bryan Menegazzo, Maria Milosh, Alex Moran, Michael Papadopoulos, David Rauch,

Michael Tiger, and Elizabeth Wagoner.

The Department also collaborated with several partners and contractors. James Parrott, Ph.D., Director of

Economic and Fiscal Policy for the Center for New York City Affairs at the New School, worked with the

Department on an analysis of existing wage and benefit standards in NYC. Suresh Naidu, Ph.D., Professor of

Economics and International and Public Affairs at Columbia University, worked with the Department in studying

the effects of the proposed rule. Professor Adam Reich, Ph.D., and Patrick Youngblood of Columbia University,

Andrew Wolf, Ph.D., of Rutgers University and the City University of New York (CUNY), Kate Sargent, Jen

Roberton, Moriah Richardson, and Dorottya Miketa of Sam Schwartz Engineering, and Hildalyn Colón

Hernández and Ligia Guallpa of the Worker's Justice Project, with the Department, developed and

implemented a field survey of delivery worker expenses and working conditions. This survey was supported, in

part, through funding from the Open Society Foundations and the Ford Foundation. Sherry Baron, M.D.,

M.P.H., Professor at the Barry Commoner Center for Health and the Environment and the Urban Studies

Department, Queens College, CUNY, contributed to the Department’s analysis of delivery workers’

occupational injuries. Steven Picker of the Food and Beverage Industry Partnership at the NYC Department of

Small Business Services (SBS), Andrew Rigie of the NYC Hospitality Alliance, and Kevin Dugan of the New

York State Restaurant Association, with their colleagues, contributed to the Department’s survey of restaurant

operators and distributed the survey questionnaire. Rodney Stiles, formerly of the NYC Taxi and Limousine

Commission (TLC), Kerem Levitas of the City of Seattle Office of Labor Standards, and Erica Groshen, Ph.D.,

Senior Economics Advisor at the Institute for Labor Relations at Cornell University, provided advice and

consultation. Julia Kite-Laidlaw, William Carry, and colleagues of the NYC Department of Transportation (NYC

DOT), Fabricio Caro and Nicole Simmons of the Fire Department of the City of New York (FDNY), and

Charlene Obernauer and Lara Maldjian of the New York Committee for Occupational Safety and Health

(NYCOSH) provided insights into the safety and health concerns relating to app delivery. Do Jun Lee, Ph.D.,

Assistant Professor at the Urban Studies Department, Queens College, CUNY, and Jing Wang, Adjunct

Assistant Professor at Brooklyn College and the College of Staten Island, CUNY, advised on the experiences

of Chinese delivery workers in NYC. Ryan Wanttaja and James DiGiovanni of TLC shared their experiences

implementing NYC’s minimum earnings standard for app for-hire service drivers. James Parrott, Suresh Naidu,

Sherry Baron, Rodney Stiles, and Kate Sargent, with her colleagues at Sam Schwartz Engineering, also

reviewed and commented on drafts of this report.

ii

Abstract

In this report, the Department discusses the findings of its study into the working conditions of restaurant

delivery workers who are engaged by apps as independent contractors in NYC. This report includes an

analysis of the pay and working conditions of this workforce, describes the Department’s proposed rule to

establish a minimum pay rate for this work, and examines the minimum pay rate’s anticipated impacts on apps,

consumers, restaurants, and workers.

The Department’s analysis is based principally on data obtained from apps and an online survey distributed to

123,000 workers who performed deliveries in NYC in the fourth quarter of 2021. The Department supplemented

these sources with an online survey distributed to all restaurants in NYC, an in-person field survey of more than

400 delivery workers, testimony from a public hearing, interviews with stakeholders and other experts, and

analysis of publicly available data on pay, benefits, and safety conditions.

The Department’s study finds that NYC’s app-based restaurant delivery workers currently earn $14.18 per hour

with tips and $7.09 per hour without tips. Delivery workers’ hourly expenses are $3.06, reducing their take

home pay to $11.12 per hour with tips and $4.03 per hour without tips. The Department also finds that app-

based restaurant delivery workers experience high rates of occupational injury.

The rate set forth in the proposed rule, after a two-year phase-in, would require restaurant apps to pay delivery

workers who are engaged as independent contractors an average hourly rate of $23.82 per hour excluding tips,

which is comprised of a $19.86 base rate, $1.70 to compensate for the absence of workers’ compensation

insurance, and $2.26 to reflect workers’ expenses. Pay at this rate will provide for parity with workers covered

by NYC’s existing minimum earnings standard for app for-hire service drivers and approximates the total

compensation app-based restaurant delivery workers would receive if classified as employees.

The Department’s study projects that the minimum pay rate will encourage apps to use workers’ time more

efficiently, increasing deliveries from 1.6 to 2.5 per hour. Apps may choose to pass their remaining increase in

labor costs to consumers through higher fees, increasing consumers’ cost of delivery by $5.18 per order, on

average. Though higher fees will moderate growth, the Department projects that the number of app deliveries

will still increase by 35% by 2025. The Department also projects that restaurants will be mostly unaffected by

the minimum pay rate but may see a modest increase in profits if consumers respond to higher app fees by

purchasing directly from restaurants.

iii

Table of Contents

1 Introduction ................................................................................................................................................... 1

2 Sources and Methods ................................................................................................................................... 2

3 Overview of the Apps, Consumers, and Restaurants ................................................................................... 6

4 Delivery Workers’ Pay and Working Conditions ......................................................................................... 12

5 Design of the Minimum Payment Standard ................................................................................................ 27

6 Effects of the Minimum Payment Standard................................................................................................. 34

7 Conclusion .................................................................................................................................................. 37

1

1 Introduction

Section 20-1522 of the NYC Administrative Code requires the Department of Consumer and Worker Protection

(the Department) to study the pay and working conditions of app-based restaurant delivery workers and, no

later than January 1, 2023, establish a minimum pay rate for their work by rule.

1

Referenced herein as the

Minimum Pay Law, this section was enacted in fall 2021 as part of a broader package of protections for app-

based restaurant delivery workers in NYC, known as the Delivery Worker Laws.

2

This report refers to the app-

based restaurant delivery workers who are covered by the Delivery Worker Laws as “app delivery workers.” A

related package of laws, also enacted in fall 2021, requires most apps to obtain a license to operate in NYC

and regulates their interactions with restaurants and consumers, including setting a limit on the fees that apps

can charge restaurants.

3

This report summarizes the results of the Department’s study of the restaurant delivery app industry in NYC,

discusses the Department’s proposed minimum pay rate, and examines the minimum pay rate’s prospective

impact on apps, consumers, workers, and restaurants. Concurrently with release of this report, the Department

is publishing the proposed rule establishing the minimum pay rate in the New York City Record.

Throughout this report, the Department refers to “apps,” “app delivery,” and “restaurant apps” as shorthand

to describe the third-party food delivery services and third-party courier services covered by the Delivery

Worker Laws. These phrases do not encompass delivery from apps that are not covered by the Delivery

Worker Laws, such as supermarket or quick-delivery convenience store apps.

4

The report is organized as follows. Section 2 briefly summarizes the Department’s sources and methods.

Section 3 describes the apps, consumers, and restaurants, providing essential context for the analysis

presented in the following sections. Section 4 describes the present conditions of app delivery workers,

including their pay, hours, modes of transportation, expenses, safety conditions, and demographics. Section 5

presents the Department’s proposed minimum pay rate and discusses its key features. Section 6 models the

minimum pay rate’s impact on apps, consumers, restaurants, and workers. Section 7 concludes. Throughout

this report, for ease of reference, key terms are introduced in bold.

1

NYC Administrative Code § 20-1522.

2

Id. §§ 20-1501–1524, 20-563.2, and 20-563.6.

3

Id. §§ 20-563–20-563.13.

4

See id. § 20-1501.

2

2 Sources and Methods

The Department’s study draws principally on data that the Department obtained from apps in response to

administrative subpoenas combined with a survey that was distributed to nearly all of the approximately

123,000 workers who performed app deliveries in NYC between October and December 2021. The study also

draws on additional sources, including a separate in-person field survey of more than 400 delivery workers, a

survey of restaurant owners and managers that was distributed to all of the approximately 23,000 restaurants in

NYC, testimony from a public hearing on delivery worker pay and working conditions, expert and stakeholder

interviews, and public information. This section provides a high-level summary of these sources and their use in

the study.

Sources

Pursuant to its authority under the Minimum Pay Law,

5

the Department issued subpoenas requesting data and

documents to all apps identified as potentially engaging independent contractors to perform restaurant

deliveries in NYC. These subpoenas resulted in the production of information covering January 1, 2021 through

June 30, 2022 from Uber Technologies, Inc., Grubhub, Inc., DoorDash Inc., and Relay Delivery, Inc.

(hereinafter referred to as Uber Eats, Grubhub, DoorDash, and Relay respectively). The Department

determined that these apps are collectively responsible for 99% of app deliveries in NYC. Through this process,

the Department also obtained data and information from all other apps it identified as engaging independent

contractors to perform deliveries in NYC. These apps are Chowbus Inc. (Chowbus), Club Feast Inc. (Club

Feast), Just Order Enterprises Corp. (Fantuan), HungryPanda US Inc. (HungryPanda), Patio Delivery, Inc.

(Patio), and GoHive Inc. (GoHive).

The information produced by Uber Eats, Grubhub, DoorDash, and Relay included four types of data. First,

record-level data for all workers who accepted an offer to perform a delivery in NYC in the fourth quarter of

2021, including the phone and email from each account profile and information about each trip, payment, and

login in the quarter. Second, ZIP code summary data on sales and payments to workers aggregated by

consumer and worker ZIP code for the fourth quarter of 2021. Third, merchant summary data on sales

aggregated by type of merchant for the fourth quarter of 2021. Fourth, weekly summary data for each week

from January 1, 2021 through June 30, 2022, including, for each app, total deliveries, hours, and pay.

The Department entered into confidentiality agreements with the apps that govern the Department’s use of data

and other information that the apps consider to be trade secrets. Though the Department used such

information in its study and deliberation to determine the minimum pay rate, the Department is not publishing

any information that the apps designated confidential pursuant to these agreements.

To obtain information about workers’ expenses, demographics, and safety conditions, the Department used the

worker contact information obtained from the apps to conduct the NYC Delivery Worker Survey, a large-scale,

representative survey of app delivery workers in NYC. The Department distributed an online survey form by

text message and email to all workers who accepted an offer to perform a delivery in NYC between October 1

and December 31, 2021 for Uber Eats, Grubhub, DoorDash, Relay, Chowbus, or HungryPanda, except a small

number of workers whose contact information was missing or suppressed. In total, between June 8 and July

26, 2022, the Department sent messages to 179,354 phone numbers and 192,546 email addresses, each

including a custom link allowing the Department to match survey responses to the other record-level data

obtained from the apps. The Department estimates that these phone numbers and emails belonged to 122,539

unique individuals, including 122,104 individuals who had worked for Uber Eats, Grubhub, DoorDash, and/or

Relay. The text messages, emails, and survey forms were delivered in Arabic, Bengali, Chinese, English,

French, Korean, Russian, Spanish, and Urdu. To limit the survey length, the Department divided its

5

Id. § 1522(a)(2).

3

questionnaire into three modules, focusing on vehicle-related expenses (including e-bike, car, and moped

expenses), non-vehicle expenses (e.g., phones), and safety and demographics. Each account was randomly

assigned to receive one of the three modules. Within each module, survey length varied due to use of

branching and skip logic. On average, respondents took four minutes and 23 seconds to complete the survey,

answering 12 questions.

The Department received 7,956 responses from workers at Uber Eats, Grubhub, DoorDash, or Relay that

satisfied its inclusion criteria,

6

consisting of 2,963 for the vehicle expense module, 2,843 for the non-vehicle

expenses module, and 2,150 for the safety and demographics module. The combined 7,956 responses

represent 6.5% of the estimated 122,104 unique individuals in the sample for these apps, after accounting for

some workers’ practice of maintaining multiple accounts. This response rate is several times the rate obtained

by leading academic researchers conducting online surveys concerning low-wage work.

7

The Department also conducted a separate in-person field survey of delivery workers, in partnership with Sam

Schwartz Engineering, a leading transportation engineering firm, Worker's Justice Project, a NYC-based

worker center and sponsor of the Los Deliveristas Unidos campaign, and the Columbia University Labor Lab,

an applied research program of Columbia University (referenced herein as the “Columbia-Sam Schwartz-

Deliveristas Survey”). The 58-item questionnaire asked workers about their work history, expenses,

experiences with discipline and non-payment on the apps, and safety conditions. Respondents were recruited

from delivery workers visiting Worker's Justice Project offices, at Los Deliveristas Unidos events held

throughout the city, and through street canvassing at locations where delivery workers are known to

congregate. Respondents completed the survey using an online form, mostly onsite at these locations. The

survey was fielded between April 25 and July 15, 2022 in Bengali, Chinese, English, French, and Spanish, and

generated 465 responses that met the Department’s inclusion criteria.

8

Though covering similar material as the

Department’s NYC Delivery Worker Survey, the two questionnaires differed in their design and wording.

To adequately consider the impacts of a minimum pay rate on restaurants, the Department fielded a survey of

restaurant owners and managers (the “NYC Restaurant Delivery Survey”). The self-administered online

survey consisted of 15 questions about the volume of deliveries at respondents’ restaurants and how these

deliveries were fulfilled. The survey was distributed by the NYC Department of Small Business Services’ (SBS)

Food and Beverage Industry Partnership, the NYC Hospitality Alliance, and the New York State Restaurant

Association to their respective contact lists of restaurant owners and managers. It was fielded between June 28

and July 22, 2022. The SBS contact list is continuously updated based on the contacts listed in restaurants’

food service establishment permit applications and is comprehensive of the approximately 23,000 restaurants

in NYC. The Department’s NYC Restaurant Delivery Survey was fielded in Chinese, English, and Spanish. The

Department received 371 responses that met the Department’s inclusion criteria,

9

equal to approximately

1.61% of the restaurants in NYC. The distribution of respondents by cuisine, borough, number of employees,

and level of service (i.e., full-service vs. limited service) was representative of all food service establishments in

NYC.

To gather additional information on delivery worker pay, working conditions, and the delivery industry, the

Department used its authority under the City Charter to hold a public hearing on June 15, 2022.

10

The

6

The Department excluded responses if the respondent did not affirm that they were over 18 and freely participating in the survey, if the

respondent reported that they had never worked for an app, if the respondent failed certain tests for reliability embedded into the

questionnaires, if more than one response was associated with a worker’s contact information, or if the record-level data obtained from apps

showed no working hours for all accounts associated with the respondent’s phone number. The Department also excluded some responses

due to a technical failure in certain text messages.

7

See, e.g., Daniel Schneider & Kristen Harknett, Schedule instability and unpredictability and worker and family health and wellbeing,

Washington Center for Equitable Growth (Sept. 2016) (discussing a survey response rate of 0.4% to Facebook advertisements targeting low-

wage service-sector workers),

http://cdn.equitablegrowth.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/12135618/091216-WP-Schedule-instability-and-

unpredictability.pdf (last accessed Oct. 28, 2022).

8

The Department excluded responses if the respondent did not affirm that they were over 18 and freely consenting to participate or if the

respondent reported that they had never worked for an app.

9

The Department excluded responses if the respondent did not affirm that they were over 18 and freely consenting to participate.

10

See NYC Charter § 2203(h).

4

Department received written or oral testimony from 73 individuals and 45 organizations.

11

Members of several

worker advocacy groups testified, including Worker's Justice Project, the NYC Food Delivery Movement,

International Alliance of Delivery Workers, New Immigrant Community Empowerment, the National

Employment Law Project, and Desis Rising Up and Moving. Representatives from DoorDash and Uber also

testified.

The Department gathered further qualitative information for the study through frequent meetings,

conversations, and interviews with delivery workers, worker advocates, app representatives, and restaurant

association representatives. The Department also heard presentations from DoorDash, Uber Eats, and

Grubhub in which they presented their views about the minimum pay rate. The Department also gathered

information from officials at other City agencies with relevant subject matter expertise, including SBS, the Fire

Department of the City of New York (FDNY), the NYC Department of Health and Mental Hygiene (DOHMH),

the NYC Taxi and Limousine Commission (TLC), and the NYC Department of Transportation (NYC DOT).

Lastly, the Department used publicly available information in portions of its study, including prior studies, news

articles, corporate financial reports, legal and regulatory documents, and public use data from government

agencies.

Methods

This report presents results from descriptive analyses of apps, consumers, restaurants, and delivery workers

(sections 3 and 4) and a structural model the Department developed to estimate the prospective effects of the

proposed minimum pay rate (section 6). Except where noted, the report presents results only for Uber Eats,

DoorDash, Grubhub, and Relay.

Though each section of the report notes the methods that produced the accompanying results, the Department

presents a few general comments here.

First, some terminology. The Department uses “delivery” to refer to the pickup and drop-off of a single order

and “trip” to refer to the unit of work offered to a delivery worker, consistent with the definition of this term in the

Delivery Worker Laws.

12

A trip usually consists of a single delivery but may include multiple deliveries. The

Department uses both terms in this report depending on context and the nature of the underlying data. When

discussing workers’ incomes, “pay” refers to the compensation paid by the app exclusive of tips, “earnings” is

the sum of pay and tips, and “net pay” and “net earnings” are pay and earnings, respectively, less expenses.

With respect to workers’ time, “hours worked” or “working time,” as used in this report, consists of all “trip

time” (i.e., the time between acceptance of a trip offer and its completion) and all “on-call time” (i.e., time in

which a worker is connected to the app in a status where they can receive or accept trip offers, excluding trip

time). Trip time includes travel to a restaurant, any time waiting for an order to be prepared, pickup at the

restaurant, travel to the destination, and drop-off with the consumer.

Second, except where noted, the Department takes care to only present statistics that reflect controls for the

common practice of workers maintaining accounts with multiple apps (“multi-apping”), including the less

frequent practice of logging into multiple apps concurrently. The Department assessed multi-apping by

matching worker accounts across apps using their account phone numbers and analyzing their responses

about the apps they work for from the Department’s NYC Delivery Worker Survey. For example, the record-

level data obtained from apps showed that 219,787 accounts were associated with a delivery in NYC at Uber

Eats, Grubhub, DoorDash, or Relay in the fourth quarter of 2021 and that these accounts logged 20.21 million

hours of working time. However, after adjustment for multi-apping, the Department estimates these accounts

11

See Delivery Worker Public Hearing Transcript, NYC Department of Consumer and Worker Protection (June 15, 2022) and Delivery Worker

Public Hearing Written Testimony, NYC Department of Consumer and Worker Protection (June 15, 2022), https: //www.nyc.gov/deliveryapps

.

12

See NYC Administrative Code § 20-1501 (“trip” is “the time spent, distance travelled, and route followed by a worker to provide delivery

services to a consumer through a third-party food delivery service or third-party courier service, including travel to a business, picking up the

food, beverage, or other goods for delivery, and taking and depositing such delivery at a different location as requested”).

5

were held by 122,104 unique individuals who spent 17.16 million hours connected to at least one app. These

adjustments reflect the Department’s estimate of the percent of workers with multiple accounts (56.3%), which

it calculated from the NYC Delivery Worker Survey, and the Department’s estimate of the percent of working

time workers logged concurrently. To estimate the latter, the Department used the record-level data it obtained

from the apps to analyze the login and logoff times of workers who used the same phone number with multiple

apps, then extrapolated to the 56.3% of the workers who maintain multiple accounts (as measured from NYC

Delivery Worker Survey data). Using this method, the Department estimates that workers spend 17.7% of

working time connected to more than one app. The Department performed this analysis separately for non-car

workers, car workers, and all workers.

Third, in its measurement of delivery worker expenses, the Department generally adheres to Internal Revenue

Service (IRS) guidelines for the deduction of business expenses on tax returns. For most cost categories, the

Department identified the items purchased by workers through its NYC Delivery Worker Survey and separately

gathered market prices from retailers or other independent sources. Using market prices rather than workers’

recollections of dollar amounts they spent generally provides for more accurate expense estimation.

Fourth, in all its analyses of its NYC Delivery Worker Survey, the Department applied post-stratification weights

to address possible non-response bias. To develop the weights, the Department defined 20 strata within the

record-level data by the mix of apps (Uber Eats only, DoorDash only, Grubhub only, Relay only, and multiple)

and quartile of hours worked. This allows the Department to control for differences in response rates between

workers with more hours and workers with fewer hours, for differences in response rates between apps, and for

differences in response rates between workers who work for multiple apps and workers who work for only one

app. The Department developed separate post-stratification weights for each survey module and for analyses

that pooled multiple modules. The Columbia-Sam Schwartz-Deliveristas Survey was drawn from a convenience

sample, so results are presented without weighting. Because responses to the Department’s NYC Restaurant

Delivery Survey showed good representativeness on observables, the Department determined weighting was

unnecessary.

Fifth, for convenience, the Department refers to the merchants on apps’ platforms as “restaurants.” Restaurant

delivery is a requirement for an app to be covered under the Delivery Worker Laws, though some covered apps

also engage workers to perform deliveries from convenience stores, grocery stores, or other retailers, in

addition to restaurants. However, non-restaurant deliveries are not provided by covered apps in NYC on a

scale sufficient to justify a differentiated analysis. Except where noted, restaurant and non-restaurant deliveries

are treated as undifferentiated throughout this report. The Department interprets its findings aware of this

limitation and determined that it does not materially impact the study results or the basis for the minimum pay

rate.

Lastly, the model used by the Department to estimate potential impacts relies on assumptions about how apps,

consumers, workers, and restaurants will respond to the minimum pay rate. It also relies on assumptions about

how the delivery industry in NYC would evolve in the absence of a minimum pay rate. Though the results

reported reflect the Department’s best estimate of likely impacts, the Department also estimated results under

alternative assumptions for key parameters and considered them in its deliberations.

6

3 Overview of the Apps, Consumers,

and Restaurants

This section provides information the Department gathered for the study on apps, consumers, and restaurants.

Apps

Apps provide either or both of two related services: a marketplace service that allows a consumer to search for

restaurants and place orders online; and a courier service, in which the app dispatches a worker to a restaurant

to pick up the food and deliver it to the consumer. If an app provides a marketplace service, NYC requires the

app to obtain a license from the Department and limits the fees it can charge restaurants.

13

If an app provides a

courier service, it is covered by the Minimum Pay Law, as well as most other provisions of the Delivery Worker

Laws.

14

In the case of the three largest delivery apps, Uber Eats, Grubhub, and DoorDash, the two services are

usually combined, so when a consumer orders through an app, a worker dispatched by that same app arrives

at the consumer’s door. A restaurant may also elect to receive orders through an app’s marketplace but still

send its own employee to do the delivery. Conversely, a restaurant might receive an order over the phone or

through its own website but then use one of the delivery apps to dispatch a worker to come pick the food up

and deliver it. A restaurant might also receive an order through one app’s marketplace but use another to fulfill

the delivery. Consumers also use apps’ marketplace service to place orders that they pick up themselves.

When app delivery first developed in NYC, it was a marketplace-only service, with the deliveries still performed

by restaurant employees. Over time, delivery by workers dispatched by apps, and engaged by the apps as

independent contractors, became the more common arrangement. Growth was rapid throughout the 2010’s

and increased sharply with the onset of the pandemic, as orders increased by more than 50% in the NYC

metro area

15

and doubled nationally.

16

Since then, the app delivery industry has not contracted to its pre-

pandemic size. Growth has only continued.

17

In NYC, there were 17% more deliveries in the first six months of

2022 than the same period in 2021,

18

and app delivery in the United States is now more than four times larger

than at the start of 2018.

19

This fast growth has resulted in delivery apps quickly becoming an important part of the NYC restaurant

market. Between March 2021 and May 2022, app deliveries accounted for $3.6 billion of the $24.7 billion in

NYC restaurant sales (15%).

20

Meals ordered through an app, either for consumer pickup or delivery by a

restaurant employee, account for an additional share of sales.

13

Id. §§ 20-563 and 20-563.1. Apps that provide a marketplace service are also required to disclose to a delivery worker how much such

worker earned in gratuities and to enter into an agreement with each restaurant on its platform that allows workers to use such restaurant’s

bathroom. See id. §§ 20-563.2 and 20-563.6.

14

Id. §§ 20-1501–1524.

15

See U.S. Food Delivery Mid-Month update: Data through 6/21/22, YipitData (June 23, 2022).

16

See Kabir Ahuja et al., Ordering in: The rapid evolution of food delivery, McKinsey and Company (Sept. 22, 2021),

https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/technology-media-and-telecommunications/our-insights/ordering-in-the-rapid-evolution-of-food-delivery

(last accessed Oct. 28, 2022).

17

See YipitData, supra note 15.

18

Department analysis of weekly aggregate data obtained from apps.

19

See Kabir Ahuja et al., supra note 16.

20

Department analysis of weekly aggregate data obtained from apps, in combination with data on taxable sales in New York. Taxable sales

and purchases by geography and industry through May 2022, NYS Department of Taxation and Finance

(July 21, 2022),

https://www.tax.ny.gov/research/stats/stat_excise/taxable_sales_and_purchases/taxable_sales_and

_purchases_open_data.htm (last accessed Sept. 30, 2022).

7

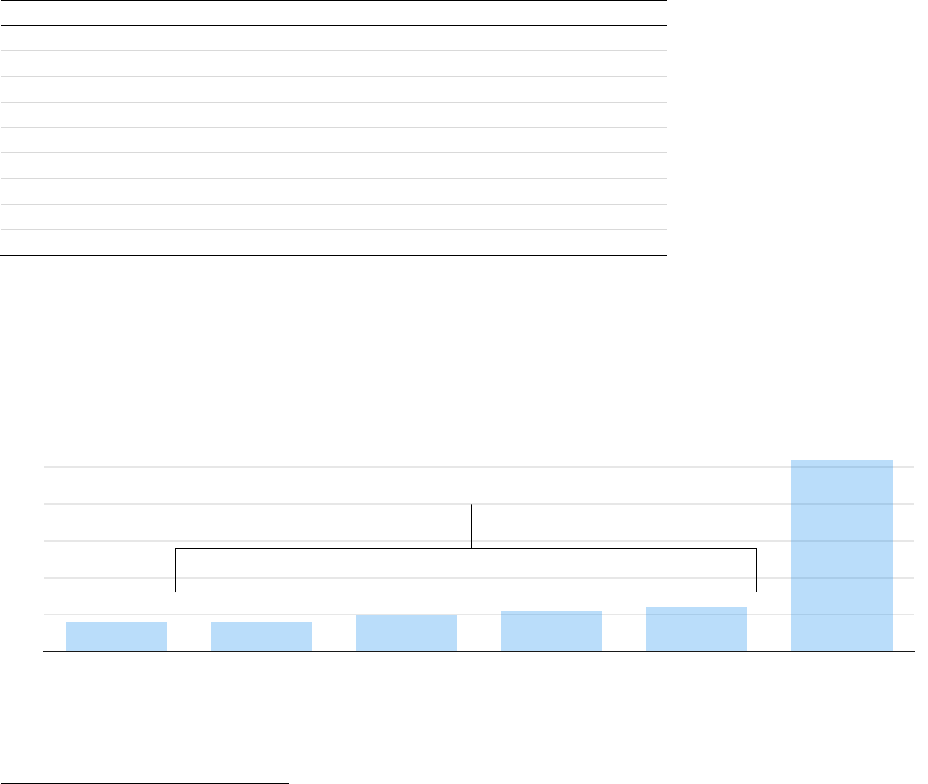

Figure 1. Restaurant Sales in NYC ($, in billions)

Values for app delivery only include deliveries in which the app engaged the delivery worker to perform the delivery. Source: Department analysis of

weekly aggregate data obtained from apps and quarterly data on taxable sales from the NYS Department of Taxation and Finance.

21

The Department has identified 10 apps that engage independent contractors to perform restaurant deliveries in

NYC. The four largest (Uber Eats, Grubhub, DoorDash, and Relay) are responsible for nearly all app deliveries

in NYC (99%), performing 124 million deliveries in NYC between July 2021 and June 2022.

22

The remainder of

the market consists of three smaller apps (Chowbus, HungryPanda, and Fantuan), one app catering business

(Club Feast), and two recent entrants to the NYC market (Patio and GoHive). Additional businesses offer

marketplace services to restaurants in NYC but do not hire, retain or engage delivery workers.

The three largest apps (Uber Eats, DoorDash, Grubhub) are all global, publicly-traded companies. According to

a report by McKinsey & Company, Uber Eats, including Postmates Inc. (Postmates) which it acquired in

2020,

23

is the market leader locally, with approximately 40% of marketplace sales in NYC.

24

Grubhub, which

merged with Seamless in 2013

25

and was purchased by the Netherlands-based Just Eat in 2021, has about

35%.

26

DoorDash, which is the largest and fastest-growing nationally,

27

holds only about a 25% share in

NYC.

28

The Department estimates that the deliveries that Uber Eats, DoorDash, and Grubhub perform in NYC

generate about 4.8% of their global delivery revenue

29

and 2.5% of their revenue across all lines of business.

30

Despite large losses, which are not uncommon for growing technology companies, the three apps had a

combined $75 billion market capitalization as of October 2, 2022.

31

Relay, the fourth largest delivery app, is an NYC-based startup, and the only one operating in NYC that does

not have a consumer-facing mobile application or website. Instead of marketing to consumers, Relay serves

restaurants as a lower-cost option to fulfill their deliveries.

32

21

See NYS Department of Taxation and Finance, supra note 20.

22

Department analysis of weekly aggregate data obtained from apps.

23

See Uber Completes Acquisition of Postmates, Uber Investor (Dec. 1, 2020), https://investor.uber.com/news-events/news/press-release-

details/2020/Uber-Completes-Acquisition-of-Postmates/default.aspx (last accessed Sept. 30, 2022).

24

See Kabir Ahuja et al., supra note 16.

25

See Seamless and Grubhub Announce Merger, PR Newswire (May 20, 2013), https://www.prnewswire.com/news-releases/seamless-and-

grubhub-announce-merger-208124841.html (last accessed Sept. 30, 2022).

26

See Kabir Ahuja et al., supra note 16.

27

Id.

28

Id.

29

See Uber Tech., Inc., Quarterly Report (Form 10-Q) (Aug. 4, 2022); see DoorDash, Inc., Quarterly Report (Form 10-Q) (Aug. 5, 2022); see

Half Year 2022 Results, Just Eat Takeaway.com (Aug. 3, 2022), https://s3.eu-c

entral-1.amazonaws.com/takeaway-corporatewebsite-dev/03-

08-2022-Press-Release-Just-Eat-Takeaway.com-Half-Year-2022-Results.pdf.

30

See id.

31

See Market capitalization of DoorDash from 2020-2022, Companies Marketcap, https://companiesmarketcap.com/doordash/marketcap (last

accessed Oct. 5, 2022); see Market capitalization of Just Eat Takeaway from 2016 to 2022, Companies Marketcap,

https://companiesmarketcap.com/just-e

at-takeaway/marketcap (last accessed Oct. 5, 2022); see Market capitalization of Uber from 2019-

2022, Companies Marketcap, https://companiesmarketcap.com/uber/marketcap (last accessed Oct. 5, 2022).

32

See Grow your restaurant’s margins by switching to Relay, Relay, https://www.relay.delivery (last accessed Sept. 30, 2022).

2

4

3.3

0.7

4.2

0.6

4.5

0.7

4.0

0.8

5.1

0.8

Mar - May

2021

Jun - Aug

2021

Sep - Nov

2021

Dec 2021 -

Feb 2022

Mar - May

2022

8

Delivery apps generate revenue by charging fees to restaurants and consumers (except for Relay, which charges

only restaurants). Delivery worker pay is the main cost they incur.

Figure 2. Unit Economics of App Delivery in NYC, July 2021 – June 2022 ($)

Source: Department analysis of weekly aggregate data obtained from apps. Visualization adapted from Kabir Ahuja et al.

33

Figure 2 breaks down the amount paid by a consumer on an average order in NYC between July 2021 and

June 2022. Moving left to right, the total cost to the consumer was $33.09, consisting of the $18.33 that went to

the restaurant, $4.11 to the worker in tips, $2.11 in taxes, $3.06 in fees charged to the consumer by the app,

and $5.48 that the app received as its share of the order subtotal (i.e., the app’s commission, usually taken by

the app as a percentage of the order subtotal). App revenue ($8.54) is the sum of the consumer fees and this

commission. Out of this, apps paid an average of $4.32 to the delivery worker, leaving a remainder of $4.22 as

the app’s gross margin.

Several insights emerge from this analysis. At $33.09, the total cost to the consumer is 39% more than the

$23.81 order subtotal (represented in Figure 2 as the sum of the restaurant share of order and the commission

charged to the restaurant). Sixty-four percent of apps’ revenue comes from the commissions they charge to

restaurants ($5.48), with the remaining 36% from fees charged to the consumer ($3.06). Apps retain 49%

($4.22) of their revenue on each order, paying out the remaining 51% to the delivery worker ($4.32). Despite

large losses at the corporate level, apps comfortably cover delivery worker pay on the average order.

Figure 3. App Revenue per Delivery and Delivery Worker Pay per Delivery in NYC ($)

Source: Department analysis of weekly aggregate data obtained from apps.

33

See Kabir Ahuja et al., supra note 16.

10

20

30

33.09

18.33

4.11

2.11

3.06

5.48

8.54

4.32

4.22

Paid by

consumer

Restaurant

share of

order

subtotal

Tip

Taxes

Fees

charged to

consumer

App share

of order

subtotal

App

revenue

Delivery

worker

pay

Gross

margin

Jan

2021

Apr

Jul

Oct

Jan

2022

Apr

Jul

0

2

4

6

8

4.20

8.84

Delivery Worker Pay

App Revenue

9

As shown in Figure 3, the spread between revenue and delivery worker pay has grown over the period for

which the Department obtained data (January 2021 – June 2022), driven by both increasing revenue and

decreasing pay.

Consumers

For consumers, the apps have increased convenience and expanded the availability of delivery. Though

restaurant delivery still represents only 0.7% of household expenditures,

34

delivery sales have been growing

faster than the restaurant industry as a whole,

35

especially among younger consumers.

36

In NYC, consumer expenditures on app delivery are greatest in the highest-income areas. In the top 20 ZIP

codes with the highest income, residents spent $36.64 per person per month on app delivery in the fourth

quarter of 2021, 73% more than the $21.15 spent by residents in the 20 ZIP codes with the lowest income. The

difference is explained mostly by higher delivery volumes. The 20 ZIP codes with the highest income ordered

1.5 deliveries per person per month in the fourth quarter of 2021 (approximately one order per person every 20

days), with an average subtotal of $24.56 per delivery, while the 20 ZIP codes with the lowest income ordered

0.9 deliveries per person per month in the same period (approximately one order per person every 33 days),

with an average subtotal of $23.35 per delivery.

37

As shown in Figure 4, deliveries, including those to both home and work addresses, are concentrated in

Manhattan below 110

th

Street and nearby areas of Brooklyn and Queens.

Figure 4. Monthly App Deliveries in NYC by ZIP Code, Fourth Quarter 2021 (in thousands)

34

Department analysis of data from the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics Current Expenditure Survey and the Purdue University Consumer

Food Insights survey. Food away from home, which includes dine-in, take-away, and delivery, comprises 3.9% of household expenditures.

Restaurant delivery (including fast food delivery) comprises 17% of this category for urban consumers. See Jayson L. Lusk & Sam Polzin,

Consumer Food Insights, Purdue University (April 2022), https://ag.purdue.edu/cfdas/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/Report_04-2022.pdf

; see

also Expenditure Surveys, 2020, U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (Sept. 2021), https://www.bls.gov/cex/tables/calendar-year/mean-item-share-

average-standard-error/cu-income-before-taxes-2020.pdf.

35

See Kabir Ahuja et al., supra note 16.

36

Id.

37

Department analysis of ZIP code summary data obtained from apps and the U.S. Census Bureau 2016-2020 American Community Survey.

See 2020 American Community Survey: 5-Year Estimates – Table B19013: Median Household Income in the Past 12 Months, U.S. Census

Bureau,

https://data.census.gov/cedsci/table?t=Income%20and%20

Poverty&g=0400000US36%248600000&y=2020&tid=ACSDT5Y2020.B19013&moe=false (last accessed Oct. 25, 2022). To limit bias from

deliveries to work addresses, the Department excludes ZIP codes with more than two jobs for every five residents from its analysis, comprising

39 of the 179 ZIP codes entirely within NYC that have ZIP-code-level U.S. Census Bureau data for income, jobs, and population. For the

remaining 140 ZIP codes, the ratio of jobs to residents is 0.25 at the top 20 by income, and 0.18 in the bottom 20 by income.

Excludes cancelled orders. Source: Department

analysis of ZIP code summary data obtained from

apps.

20

40

60

80

100

120

140

160

180

200

220

10

Restaurants

For NYC restaurants, the growth of app delivery has had a mixed impact. During the early phases of the

pandemic, app delivery provided a lifeline, especially to restaurants that did not previously offer delivery by

allowing them to pivot quickly to delivery and stay in business.

38

For restaurants that previously offered

delivery, the apps have allowed them to expand their service areas, increase delivery sales, and attract new

consumers (although also at the cost of increased competition).

39

However, the switch in consumer demand towards app delivery has left restaurants highly dependent on the

apps, forcing them to accept high commissions (23% of the order subtotal is the maximum apps can charge to

restaurants under NYC law).

40

A recent analysis found that margins on app deliveries were slightly negative for

restaurants nationally, and that profitability tends to decline as the delivery share of sales increases.

41

Based on responses to its NYC Restaurant Delivery Survey, the Department estimates that 92% of NYC

restaurants prepare orders for delivery, and that on average, delivery represents 27% of sales.

Table 1. Restaurant Delivery Sales in NYC

Delivery as a Percent of Sales (%)

Distribution of Restaurants (%)

0

8

1 – 10

22

10 – 20

16

20 – 30

18

30 – 40

12

40 – 50

6

50 – 60

6

60 – 70

5

70+

7

While most restaurants use apps to fulfill deliveries, the industry has not abandoned dispatching their own

employees. Fifty-two percent of restaurants only use workers dispatched by apps to make the delivery,

compared to 40% that employ their own delivery workers, which they either rely on exclusively (8%) or more

commonly in combination with workers dispatched by the apps (32%).

Figure 5. Distribution of Restaurants in NYC, by Delivery Arrangement (%)

Percentages do not sum to due to rounding. Source: Department analysis of data from the NYC Restaurant Delivery Survey.

38

See NYC Council, Committee Report of the Governmental Affairs Division (Aug. 26, 2021) at 13-14.

39

Id. at 4-5.

40

See NYC Administrative Code § 20-563.3.

41

See Kabir Ahuja et al., supra note 16.

10

20

30

40

50

8

8

10

11

12

52

No delivery

Own employees

only

Mostly own

employees

Even mix

Mostly delivery

services

Delivery

services only

40

Interpretation: Delivery is between

1% and 10% of sales for 22% of

restaurants in NYC. Source:

Department analysis of data from

the NYC Restaurant Delivery

Survey.

11

Restaurants tend to use multiple apps for delivery with 53% using three or more apps and only 14% relying on

a single app for deliveries.

Figure 6. Distribution of Restaurants in NYC, by Number of Apps Used for Delivery (%)

Percentages do not sum to 100 due to rounding. “0” includes restaurants that do not prepare orders for delivery and restaurants that only use their own

employees for delivery. Source: Department analysis of data from the NYC Restaurant Delivery Survey.

Uber, Grubhub, and DoorDash all deliver for between 61% and 67% of restaurants, while Relay delivers for

23%. No other app was used for deliveries by more than 2% of restaurants.

Figure 7. Distribution of Restaurants in NYC, by App Used for Delivery (%)

Grubhub includes Seamless. DoorDash includes Caviar. Uber Eats includes Postmates. “No app” includes restaurants that do not prepare orders for

delivery and restaurants that only use their own employees for delivery.

Source: Department analysis of data from the NYC Restaurant Delivery

Survey.

Overall, among respondents that prepare orders for delivery, 96% use the apps as part of their operations,

whether for online ordering, delivery, or both.

42

42

Department analysis of data from the NYC Restaurant Delivery Survey.

10

20

30

16

14

18

37

14

2

0

1

2

3

4

5 or more

Grubhub

DoorDash

Uber Eats

Relay

No app

Other apps

Chowbus

Fantuan

HungryPanda

67

63

61

23

16

2

2

2

1

12

4 Delivery Workers’ Pay and Working

Conditions

In this section, the Department presents its estimates of the number of people who work for the restaurant

delivery apps and describes their demographics, modes of transportation, delivery distances, hours of work,

pay and tips, expenses, net pay and earnings, earnings and expense risks, and safety conditions.

Workforce Size

The Department estimates that as of the second quarter of 2022, 61,000 delivery workers were working for

restaurant apps in NYC in any given week.

43

However, the total number of people working for the apps over

longer time periods may be considerably higher. For instance, at the four largest apps, in the fourth quarter of

2021 there were 219,787 worker accounts associated with at least one delivery in NYC. After adjusting for

multi-apping, the Department estimates that these accounts were held by 122,104 individuals, comprising 4%

of all New Yorkers who had any paid employment or self-employment during these months.

44

Though a large workforce, many workers appear to have only limited engagement with the apps. In the fourth

quarter of 2021, 39% of the unique worker phone numbers in the Department’s data were associated with

deliveries in two or fewer weeks.

Demographics

App delivery workers are predominantly aged 18-34 (57%), male (75%), and non-white and/or Hispanic (91%).

Table 2. Demographics of App Delivery Workers in NYC and All Workers in NYC (%)

App Delivery Workers

All Workers

Age

18-34

57

37

35-54

38

41

55-64

4

15

65+

<1

7

Gender

Male

75

52

Female

24

47

Other responses

1

1

Race/Ethnicity

Hispanic, of any race

47

20

Black or African American, non-Hispanic

25

20

Asian or Pacific Islander, non-Hispanic

16

18

White, non-Hispanic

9

41

Other responses

3

1

English Proficiency

Speaks English less than very well

39

19

43

Department analysis of weekly aggregate data obtained from apps.

44

Department analysis of record-level data obtained from apps and the NYC Delivery Worker Survey, in combination with data from the U.S.

Census Bureau Current Population Survey for April to June 2022. See Sarah Flood et al., Integrated Public Use Microdata Series, Current

Population Survey: Version 10.0, IPUMS CPS, https://doi.org/10.18128/D030.V10.0

(last accessed Oct. 25, 2022).

Source: Demographics for app

delivery workers are from the NYC

Delivery Worker Survey.

Demographics for all workers are

from the July 2020 to June 2022

U.S. Census Bureau Current

Population Survey (for all except

English proficiency) and 2020

American Community Survey (for

English proficiency).

13

Modes of Transportation

Workers perform app deliveries using four main modes of transportation: mopeds, e-bikes, cars, and walking.

Mopeds, also known as limited use motorcycles, are subject to many of the same regulations as ordinary

motorcycles. Among other requirements, this means they must have a vehicle identification number (VIN) and

can only be driven if they are registered with the New York State Department of Motor Vehicles (DMV) and

operated by a licensed driver.

45

Depending on the vehicle’s maximum speed, the driver must also carry liability

insurance.

46

Mopeds are generally required to follow the same driving rules as cars and ordinary motorcycles.

47

By contrast, the regulation of e-bikes, which became legal to operate in NYC in November 2020,

48

is similar to

bicycles. This means that a license, registration, and insurance are not required.

49

E-bikes are generally

required to follow the same driving rules as bicycles.

50

Figure 8. E-bikes and Mopeds

E-bike Moped

Image of Class 2 E-bike and Class C Moped. Source: NYC Department of Transportation.

51

Mopeds do not have functional pedals and are operated from an upright seated position with feet placed on a

center platform. They may be gas or electric. E-bikes have functional pedals paired with an electric motor. In

some models, the motor is only engaged while pedaling, known as “pedal-assist.” However, delivery workers

typically use models where the motor is engaged from the handle, known as “throttle e-bikes.”

Though apps maintain self-reported data concerning workers’ modes of transportation, there is significant

uncertainty about the actual modes in use. Some apps offer trips to a worker based on their self-reported mode

of transportation, giving workers an incentive to be strategic in the mode that they report. Further, the mopeds

typically used by delivery workers are commonly mis-labelled by sellers as “e-bikes.” These mopeds often lack

VINs, meaning they cannot be registered or insured and, as a result, are illegal to both drive and sell in New

York State.

52

Apps are required to ensure their delivery workers do not use illegal mopeds,

53

though casual

inspection on the street suggests workers commonly use these mopeds for app delivery, and NYC DOT reports

their use is increasing.

54

For these reasons, the Department believes that most moped users have misreported their vehicles as e-bikes

both to the apps and in the Department’s NYC Delivery Worker Survey. As a result, throughout this report,

references to e-bikes in either the data the Department obtained from apps or the NYC Delivery Worker Survey

should be assumed to include a significant number of illegal mopeds. Separately, apps did identify a small

45

See Electric Bicycles & More, NYC Department of Transportation, https://www1.nyc.gov/html/dot/downloads/pdf/ebikes-more-english.pdf.

46

See Register a moped, NYS Department of Motor Vehicles, https://dmv.ny.gov/registration/register-moped (last accessed Sept 30, 2022).

47

See NYC Department of Transportation, supra note 45.

48

See Rules of the NYC Department of Transportation (34 RCNY) § 4-01.

49

See NYC Department of Transportation, supra note 45.

50

See id.

51

Id.

52

See New York State Vehicle and Traffic Law §§ 401(1) and 2267.

53

See NYC Administrative Code § 10-157.

54

Hearing Written Testimony at 4 (letter of Benjamin Smith, NYC Department of Transportation).

14

number of motorcycle users in their data, which the Department believes consist mostly of workers using

vehicles properly classed as motorcycles and possibly some users of legal mopeds.

Still, with these caveats, the Department finds that non-car modes of transportation predominate, especially e-

bikes (including mopeds misreported as e-bikes). Based on the apps’ data, non-car modes of transportation

account for 56% of workers but 69% of hours worked and 78% of deliveries. The difference in these

distributions is explained by higher hours per week, and deliveries per hour worked for workers using a non-car

mode of transportation.

Table 3. App Delivery Workers, Hours, and Deliveries, by Mode of Transportation, NYC, Fourth Quarter 2021

Workers (%) Hours (%) Deliveries (%) Hours per Week

Deliveries per

Hour

Non-Car

56.1

69.4

77.7

22.2

1.869

E-bike

46.1

54.1

65.8

21.3

2.030

Walking

8.7

13.5

10.2

25.7

1.266

Motorcycle

1.3

1.8

1.7

25.2

1.530

Other

<0.1

<0.1

<0.1

17.6

1.626

Car

43.9

30.6

22.4

17.5

1.128

Percentages may not sum due to rounding. Hours per week calculation excludes weeks in which a worker did not perform work for any delivery app.

Source: Department analysis of record-level data obtained from apps.

Examining trends over time, the Department finds a steady movement away from cars.

Figure 9. Percent of App Deliveries in NYC Performed by Cars (%)

Source: Department analysis of weekly aggregate data obtained from apps.

Delivery Distances

Workers travel 1.77 miles for an average delivery, including travel to the pickup location and between the

pickup and drop-off locations. Workers using cars tend to perform longer deliveries.

Jan

2021

Feb

Mar

Apr

May

Jun

Jul

Aug

Sep

Oct

Nov

Dec

Jan

2022

Feb

Mar

Apr

0

10

20

30

40

15

Table 4. App Delivery Trip Distances in NYC, by Mode of Transportation, Fourth Quarter 2021

E-bike

Car

All Modes

Miles per trip (mean)

1.45

3.12

1.77

Distribution of trips, by miles travelled (%)

0.00 - 0.49

9

2

15

0.50 - 0.99

26

8

21

1.00 - 1.49

26

12

19

1.50 - 1.99

17

13

14

2.00 - 2.49

11

12

10

2.50 - 2.99

6

10

7

3.00 - 3.49

3

9

4

3.50 - 3.99

1

8

3

4.00+

1

26

7

Total

100

100

100

Distances are as estimated by apps based on offer, pickup, and drop-off locations. “All modes” includes e-bikes, cars, motorcycles, and walkers.

Source: Department analysis of record-level data obtained from apps.

Hours of Work

Delivery workers generally can connect to the app when they wish but, depending on demand, apps may block

a worker from initiating a status in which they can receive trip offers or may offer trips only infrequently. Some

apps permit workers to pre-schedule shifts, guaranteeing them access to the platform during specific hours (but

limiting their future earnings opportunities if they miss or cancel their shift).

55

Some apps also provide

incentives to hit production targets over specific periods.

56

Once connected to the app in an active status,

workers receive trip offers, which they may accept or decline, though some apps condition future earnings

opportunities on acceptance rates.

57

Findings from the Department’s NYC Delivery Worker Survey indicate that app delivery is the main or only job

for most workers, especially among those using e-bikes.

Table 5. Percent of NYC App Delivery Workers who Perform App Delivery as their Only, Main, or Secondary Job, by

Mode of Transportation (%)

E-bike

Car

Main or only job

77

56

Only

70

51

Main

7

5

Secondary

23

44

Source: Department analysis of data from the NYC Delivery Worker Survey.

Responses also indicate that 46.6% of e-bike workers and 34.9% of car drivers perform deliveries on a full-time

basis.

55

See Make money on your schedule, Grubhub, Inc., https://driver.grubhub.com/scheduling (last accessed Oct. 5, 2022); see How to

schedule and/or edit a Dash, DoorDash, Inc., https://help.doordash.com/

dashers/s/article/How-to-schedule-a-dash?language=en_US (last accessed Oct. 5, 2022).

56

See How does Quest work?, Uber Technologies, Inc., https://help.uber.com/driving-and-delivering/article/how-does-quest-

work?nodeId=3a43fa72-4fc2-42d0-bc1d-63c4c0bddb9d (last accessed Oct. 5, 2022); see Top Dasher, DoorDash, Inc.

https://help.doordash.com/dashers/s/article/Top-Dasher?language=en_US (last accessed Oct. 5, 2022).

57

See Grubhub and DoorDash, supra note 55.

16

Table 6. Percent of NYC App Delivery Workers who Work Full-time and Part-time, by Mode of Transportation (%)

E-bike

Car

Full-time

46.6

34.9

Part-time

53.4

65.1

Full-time is defined as 30 or more hours per week. Part-time is defined as fewer than 30 hours per week. Source: Department analysis of data from the

NYC Delivery Worker Survey.

As shown in Figure 10, more delivery workers connect to the apps during peak dinner hours (left panel), during

which they spend more of their time engaged in trips (middle panel) and perform more deliveries per hour (right

panel). The right panel also shows that, throughout the day, car drivers perform substantially fewer deliveries

per hour than e-bike workers.

Figure 10. Activity on Delivery Apps in NYC by Time of Day, Fourth Quarter 2021

Workers engaged Utilization (%) Deliveries per hour

“Workers engaged” is the daily average number of workers connected to an app. “Utilization” is the percent of working time spent engaged in a trip.

“Deliveries per hour” is the average per worker for each category. “All workers” includes e-bikes, cars, motorcycles, and walkers. Source: Department

analysis of record-level data obtained from apps.

Weekly hours average 21.3 for e-bike workers, 17.5 for car drivers, and 20.7 overall.

58

Workers spend 61% of their working time engaged in a trip and 39% on-call. During on-call time, they receive a

trip offer every 4 minutes and accept an offer every 11 minutes, on average. Time spent waiting at a restaurant

for an order to be prepared is included within trip time and not separately identifiable in the data obtained from

the apps.

Apps benefit from workers’ on-call time in two ways. First, the high availability of workers helps the apps

provide short delivery windows to consumers. Second, it helps apps minimize pay per trip because a larger

pool of available workers is more likely to contain at least one worker willing to accept a low offer.

58

Department analysis of record-level data obtained from apps. For each delivery worker, this analysis excludes weeks in which the worker

did not perform any work for delivery apps.

0

2,000

4,000

6,000

8,000

10,000

12,000

12 AM 12 PM 10 PM

0

25

50

75

100

12 AM 12 PM 10 PM

0.0

0.5

1.0

1.5

2.0

2.5

3.0

12 AM 12 PM 10 PM

E-bike

All

Workers

All

Workers

All

Workers

E-bike

E-bike

17

Table 7. Trip Time and On-Call Time of App Delivery Workers in NYC, Fourth Quarter 2021

Analysis performed at the worker account level,

without adjustment for multi-apping. Source:

Department analysis of record-level data obtained

from apps.

To secure better availability of work, workers often maintain active accounts on more than one app and

sometimes connect to more than one app concurrently. Analyzing the record-level data obtained from apps,

together with the Department’s NYC Delivery Worker Survey, the Department finds that 56.3% of delivery

workers work for more than one app and that 17.7% of working time is logged concurrently.

59

Several worker

advocates testified at the Department’s public hearing that maintenance of multiple accounts was common.

60

Pay and Tips

Apps pay workers using a variety of methods. Uber Eats, Grubhub, and DoorDash predominantly pay workers

on a per-trip basis with proprietary algorithms determining the payment for each trip. These workers also

receive 5.6% of their pay in the form of bonuses or incentives not tied to specific trips.

61

Relay pays workers a

regular rate of $12.50 per hour worked, including on-call time.

Workers at Uber Eats, Grubhub, DoorDash, and Relay earn an average of $14.18 per hour worked, split evenly

between pay and tips.

62

Hourly pay and tips are higher for e-bike workers due to the higher number of

deliveries they perform per hour. Pay per trip is slightly higher for cars than for e-bikes, reflecting longer trip

distances.

Table 8. Hourly Pay and Tips of NYC App Delivery Workers, by Mode of Transportation, Fourth Quarter

2021 ($)

Values are earnings, pay, and tips

divided by all hours and all trips,

respectively, which may differ from

the earnings, pay, and tips of the

average worker. “All modes” includes

e-bikes, cars, motorcycles, and

walkers. Source: Department analysis

of record-level data obtained from

apps.

By several measures, pay is trending down. This may be because apps used higher pay to recruit more

workers during the pandemic and then began reducing pay once labor supply expanded.

59

Department analysis of record-level data obtained from apps and the NYC Delivery Worker Survey.

60

Hearing Transcript at 19 (statement of Ligia Guallpa, Worker's Justice Project); Hearing Written Testimony at 12 (letter of NYC Comptroller

Brad Lander), at 16, 21 (letter of Hildalyn Colón Hernández, Los Deliveristas Unidos/Worker’s Justice Proect).

61

Department analysis of weekly aggregate data obtained from apps.

62

As explained in section 2, the term “pay” refers to the compensation paid by the app, excluding tips, and the term “earnings” refers to the

sum of pay and tips.

Percent of Hours Worked (%)

Trip time

61

On-call time

39

Login to first trip

9

Between trips

6

Last trip to logoff

12

Login to logoff with no trip

12

E-bike

Car

All Modes

Per hour

Earnings

14.69

13.46

14.18

Pay

7.14

7.12

7.09

Tips

7.55

6.34

7.09

Per trip

Earnings

7.86

11.93

8.64

Pay

3.82

6.31

4.32

Tips

4.04

5.62

4.32

18

Figure 11. App Delivery Worker Pay in NYC ($)

Analysis performed at the app level, without adjustment for multi-apping. Source: Department analysis of weekly aggregate data obtained from apps.

Comparing the first quarter of 2021 to the second quarter of 2022, pay per delivery declined from $6.38 to

$4.29 (23%).

Expenses

As independent contractors, app delivery workers are responsible for selecting, acquiring, and maintaining the

equipment and services needed to connect to the apps and perform deliveries.

63

Apps do not reimburse or

separately compensate delivery workers for these costs.

The Department estimated average hourly expenses overall and for five groups of workers: e-bike users, car

drivers, gas moped users, electric moped users, and walkers.

Table 9. Hourly Expenses of App Delivery Workers in NYC, by Mode of Transportation ($)

“All Modes” includes e-bikes, cars,

motorcycles, and walkers. For purposes

of calculating expenses for “All Modes,”

motorcycles were assumed to have the

same expenses as mopeds. “$0.00

*

”

indicates expense categories treated as

$0.00 by assumption. Source:

Department analysis of the NYC Delivery

Worker Survey, record-level data

obtained from apps, testimony submitted

by Uber Eats and DoorDash to the

Department’s June 2022 public hearing,

64

and price quotes from internet research,

PriceDigests,

65

and visits to NYC

retailers.

63

An exception exists for delivery bags, which apps must provide to delivery workers, effective April 22, 2022. See NYC Administrative Code §

20-1524.

64

Hearing Written Testimony at 60, 67-73 (letter of DoorDash, Inc.).

65

See Passenger Vehicles Auto Red Book, Price Digests, https://app.pricedigests.com/?classification=Pass

enger%20Vehicles (last accessed Oct. 5, 2022).

Jan

2021

Apr

Jul

Oct

Jan

2022

Apr

Jul

4

8

12

16

20

11.70

5.72

4.20

Per Trip Hour

Per Hour Worked

Per Delivery

E-bike

Car

All Modes

Vehicle

1.64

2.92

1.78

Depreciation

0.32

1.53

0.65

License, registration, and insurance

0.00

*

1.03

0.28

Casualty & theft loss

0.05

0.00

*

0.03

Batteries/gas

0.86

0.11

0.51

Maintenance

0.15

0.25

0.16

Accessories

0.26

0.00

*

0.15

Phone

0.62

0.57

0.58

Phone purchases

0.35

0.28

0.31

Data plan

0.27

0.29

0.27

Vehicle and phone subtotal

2.26

3.49

2.36

Tickets

0.44

1.37

0.70

Total

2.70

4.86

3.06

19

For e-bike workers, batteries are the largest expense (32% of total expenses), followed by phone costs

(including both the device and data plan) (23%). For car drivers, the largest expense is depreciation (31%),

followed by traffic or parking tickets (28%).

The Department estimated the expenses of e-bike workers as follows. For depreciation, the Department

obtained the purchase price of a new e-bike through visits to NYC retailers ($1,800), applied five-year straight-

line depreciation consistent with IRS principles, and then reduced this amount to reflect the probability of loss

due to casualty or theft (5.88% annually),

66

which the Department estimated from its NYC Delivery Worker

Survey. For casualty and theft loss, the Department multiplied the probability of a loss incident by the expected

depreciated value of the e-bike at the time of incident ($959.13), assuming constant probabilities of loss during

the e-bike’s useful life. For batteries, the Department obtained the purchase price of a new battery by visiting

NYC retailers ($550) and multiplied the cost by workers’ average replacement rate (1.74 per year), which the

Department measured from its NYC Delivery Worker Survey. For maintenance costs, the Department used the

estimate of e-bike maintenance costs per mile provided by Uber Eats and DoorDash ($0.067)

67

and the

average trip distance per hour worked (2.17 miles), which the Department estimated from the record-level data

obtained from apps. For accessories, the Department used its NYC Delivery Worker Survey to estimate the

annual probabilities of purchasing handlebar gloves (63%), bike racks (37%), baskets (38%), helmets (67%),

lights (58%), horns (32%), reflective vests (39%), locks (74%), alarms (32%), anti-theft cameras (13%), anti-

theft GPS systems (32%), and clothes, shoes or rain gear for work (84%), and quoted prices for each

accessory from NYC retailers and internet sellers. For phone purchases, the Department used its NYC Delivery

Worker Survey to identify the mix of phone models used by delivery workers and quotes from internet sellers to

estimate the average purchase price ($721) as well as the average discounts or proceeds on trade-ins and

resales ($597). The Department then obtained the net expense by multiplying these amounts by the

frequencies of purchase (1.74 per year) and trade-in or resale (0.45 per year), respectively, from its NYC

Delivery Worker Survey. For data plans, the Department used the average cost of a single-line, unlimited data

plan as quoted from major carriers ($63.33 per month).

68

For both phone purchases and data plans, the

Department reduced estimated expenses to reflect percent use in app delivery, assuming 145.17 hours of

personal phone use per month, which is the mean of four recent studies,

69

and 21.3 hours of app delivery use

per week, consistent with the average for e-bike workers. For tickets, the Department used the frequencies of

receiving a ticket and the costs per ticket reported in its NYC Delivery Worker Survey. The Department then

converted all expenses into hourly rates based on e-bike workers’ average of 21.3 hours per week, except for

maintenance, for which an hourly rate was derived as described above (i.e., from data reflecting cost per mile

and miles per hour of working time).

To estimate car drivers’ expenses, the Department took the same approach as with e-bike workers for phone

purchases, data plans, and tickets as described above and accounted for vehicle-related expenses as follows.

For depreciation, the Department used its NYC Delivery Worker Survey to identify the model and year of cars

used by delivery workers, together with a database on historical fair market values

70

to determine bases for

depreciation. With this information, the Department then calculated depreciation using the five-year straight-line

66

Casualty or theft losses can be claimed as business expenses under IRS guidelines. A casualty loss is a sudden, unexpected destruction of

property. See Topic No. 515 Casualty, Disaster, and Theft Losses, IRS, https://www.irs.gov/taxtopics/tc515

(last accessed Oct. 28, 2022).

67

Hearing Written Testimony at 67, 70-71 (letter of DoorDash, Inc. and Uber Technologies, Inc.).

68

See Get Our Best Unlimited Plans Ever, Verizon, https://www.verizon.com/plans/unlimited/#plans (last accessed June 23, 2022); Bring

Your Own Device, AT&T, https://www.att.com/buy/wireless/byod/deviceconfig (last accessed June 23, 2022); Compare Our Best Unlimited

Data Cell Phone Plans, T-Mobile USA, Inc., https://www.t-mobile.com/cell-phone-plans?|NTNAV=tNav:Plans:Magenta (last accessed June 23,

2022). Department’s calculation assumes workers enroll in Autopay to receive discounts of $5-$10 per month, depending on carrier.

69

See Trevor Wheelwright, 2022 Cell Phone Usage Statistics: How Obsessed Are We?, Reviews.org (Jan. 2022),

https://www.reviews.org/mobile/cell-phone-addiction/

(last accessed Oct. 30, 2022); Laura Ceci, How Much Time on Average Do You Spend

on Your Phone on a Daily Basis?, Statista (Feb. 2021), https://www.statista.com/statistics/1224510/time-spent-per-day-on-smartphone-us/

(last accessed Oct. 30, 2022); Sam Medley, The Average iPhone User Spends a Full Work Week on Their Phone, a New Report Claims,

Notebookcheck (Sept. 2021), https://www.notebookcheck.

net/The-average-iPhone-user-spends-a-full-work-week-on-their-phone-a-new-

report-claims.562797.0.html (last accessed Oct. 30, 2022); Eileen Brown, Americans Spend Far More Time on Their Smartphones than they

Think, ZDNET (Apr. 2019), https://www.zdnet.com/article/americans-spend-far-more-time-on-their-smartphones-than-they-think (last accessed

Oct. 30, 2022).

70

See Price Digests, supra note 65.

20

method. For license and registration, the Department obtained fee amounts from the DMV,

71

and for insurance,

the Department used a published estimate of average insurance costs.

72

For depreciation, license, registration,

and insurance, the Department reduced estimated expenses by the proportion of time delivery workers use

their car for app delivery relative to other uses, which it obtained from its NYC Delivery Worker Survey. The

Department then converted the depreciation, license, registration, and insurance expenses into hourly rates

based on car drivers’ average of 17.5 hours per week. For gas, the Department used a published estimate of

average per-gallon costs in the NYC area

73

and estimated use based on average trip distance per hour of

working time, as measured from the record-level data, and average gas mileage of 25 miles per gallon, which

the Department derived from the gas mileages reported from manufacturers and the mix of vehicles identified

in its NYC Delivery Worker Survey. For maintenance, the Department used the American Automobile

Association’s estimate of per-mile maintenance costs

74

and average trip distances per hour of working time, as

measured from the record-level data.

Though the costs presented in Table 9 account for most delivery worker expenses, the Department omitted

some work-related costs. This includes the cost of time spent maintaining equipment and for vehicle storage,

for which the Department was unable to obtain reliable estimates, and out-of-pocket medical expenses for

work-related injuries.

Because the Department’s NYC Delivery Worker Survey includes many responses in which an illegal moped

was misreported as an e-bike, the Department performed a supplemental analysis to address the possibility

that this might bias its estimates of true e-bike expenses. To assess this possibility, the Department examined

differences in responses to its NYC Delivery Worker Survey between the 229 self-identified moped users and

the 2,316 self-identified e-bike users and determined that misreporting of illegal mopeds did not have a material

impact.

The Department’s expense analysis follows standard cost accounting principles, in which the total cost of an

input is allocated to a function (in this case, app delivery) based on percent use. However, some workers may

base their decision to enter and stay in app delivery on their marginal costs, which for car drivers may be