6.1

V

ALUATION OF 6

L

EASEHOLD INTERESTS

Introduction

Chapter 5 illustrated how to appraise the market value of a commercial property, based on a combination of

the property’s income from its leases and market evidence from the sale of other similar properties. This

highlights the most common form of appraisal assignment for income-producing properties.

In this chapter, we turn our attention to valuing the leasehold interests specifically. When investors buy and

sell leased commercial real estate, what is occurring is the transfer of a bundle of leasehold interests. These

leases are a form of real property and may in themselves have market value. Leasehold market value can be

estimated using the same basic income valuation approaches illustrated in Chapter 5, though with some

variations. Note also that in valuing the leasehold interest, this may also serve as an adjustment to the overall

property value in certain circumstances, such as below-market lease rates.

Consider a leasehold valuation issue – assume you are a real estate analyst or appraiser advising a vendor or

purchaser of a leased commercial building. Your analysis will include a review of the current cash flow

from lease contracts, and prospects for dips or increases in cash flows as leases roll over and market

conditions change. What if the total base rent for your client’s property is not sustainable due to a tenant

with a failed business who has missed a number of monthly payments? The space can only be rented for a

market rent which is $4.00 per square foot (psf) less than contract rent due to a rising vacancy rate in the

market, and the lease-up period will be extended. Let’s assume this shortfall translates into a $16,000 dip in

net income per annum. If the prevailing overall capitalization rate for the property is 6%, there is an

immediate $267,000 (rounded) impact on the property value. This example is only about one tenant. What if

a number of tenants are having problems? How will this influence the property’s market value?

In this chapter, our goal is to emphasize the importance of careful analysis and interpretation of lease

agreements to determine the impact on property cash-flow, and the overall risk associated with a real estate

asset. Integral to our analysis is the identification and financial measurement of the various lease interests

which arise in commercial properties as a result of lessor and lessee negotiations.

We build on our earlier discussion of the leasing process in Chapters 3 and 4, and cover the following

topics:

• identification and separation of lease interests; and

• valuation of the lease interests through a series of mathematical examples.

The intent of this chapter is to provide the basic skills required in the valuation of various leasehold

interests.

Chapter 6

6.2

Identification of Interests in a Leased Property

Various legal interests may exist in a leased property. A real estate analyst must be able to recognize:

• how interests arise in a property;

• limitations on the extent of the interests; and

• the methods used to value each interest.

The valuation of an interest held by lessor, lessee, or sub-lessee is challenging for a number of reasons.

First, this is an assignment that most valuators and consultants encounter rarely. Secondly, the identification

and quantification of an interest is difficult when market information is limited. Thirdly, there are

exceptions, nuances, and limitations in the valuation process which must be recognized. Lastly, the

mathematics of leasehold valuation tends to become involved and complicated.

However, whatever the interest to be valued or technique to be used, the final outcome must stand the test of

market value. The difficulty arises when some interests are so unique that they fail the notion of an open and

competitive market or the market conditions of willing buyer/willing seller.

At this point you are probably wishing you could fast forward to the next chapter….not so fast. We will

demonstrate, through many examples, how you can tackle the most common and difficult valuation of

interests in leased property. As in the case of almost all real property analysis, you will find that success

comes with a combined understanding of the appropriate analytical process coupled with experience and

common sense.

Identification of Interests

Our initial focus is to identify the distinct interests related to the leased property and explain the valuation

methods used to value each interest. Let’s begin at the top, the fee simple interest held by the owner of the

property and work on down the hierarchy of possible interests so you have a picture of how the various

interests are related.

Fee Simple Interest

The fee simple interest is the most complete interest in real estate where the title is only encumbered by the

four powers of government: taxation, land-use controls (police power), eminent domain, and escheat

(reversion of title to government when an owner dies intestate). To capture the concept of complete

ownership, the unencumbered fee simple interest is sometimes referred to as a complete bundle of rights. In

reality, the title to most property is less than unencumbered fee simple since it can be affected by a

mortgage, easement, covenant, or some other form of charge affecting the bundle of rights.

Valuation of the fee simple estate is the most common property valuation assignment for appraisers. The

value is relevant not only to the owner who has encumbered the property with lease agreements, mortgages

and other charges, but also to a lender or a potential investor. If an appraiser is asked to value a property

with leases in place, the assignment will be a valuation of the encumbered fee simple interest. Moreover, in

all Canadian jurisdictions, assessors are required by legislation to determine the fee simple estate for

property assessment and taxation purposes. This legal requirement is intended to ensure that assessments are

consistent and equitable.

Valuation of Leasehold Interests

6.3

An important initial task for an appraiser who is valuing the fee simple interest in a leased property is to

determine whether the lease rents are representative of market rents and whether adjustments are required to

the property rents or the overall capitalization rate to reflect market conditions. The capitalized value of the

fee simple interest in property is typically determined by capitalizing market rent for the property, with a

market derived overall capitalization rate.

Let’s now move to the next level of ownership interest: the leased fee estate.

Leased Fee Estate

The leased fee estate is the ownership interest held by the lessor (landlord), which includes the right to

receive the rent specified in the lease, plus the reversionary right when the lease expires.

When a fee simple owner (lessor) leases their property to a second party (the lessee), a partial estate is

created. The lessor’s property interest is known as the leased fee estate. While the lessor retains ownership

of the property, the legal title is subject to the rights conveyed in the lease. The challenge in the valuation of

the leased fee or lessor’s interest is determining the rights conveyed in the lease to receive rent and the

extent to which the lease improvements have value at the expiry of the lease.

You are probably wondering how the value of a leased fee interest is different from the value of fee simple

property. The answer is that the two values may not be different if the lease contract rents reflect market

rents. Remember – a key initial step in the appraisal process is the identification of whether the rents are at

market. In contrast, the goal of a leased fee valuation is to analyze the contract rents in the lease

agreement(s) rather than market rent.

A landlord or lessee may require a valuation of the leased fee interest in their income property for:

• corporate re-structuring;

• sale of partnership interests, wind-ups;

• estate purposes;

• sale of the property; or

• long-term ground leases associated with build-to-suit projects such as Big Box Stores.

Leased fee valuation assignments may be associated with long-term lease agreements where there is little

opportunity to achieve current market rent. For example, a 30 year ground lease may be structured to

restrict periodic rent escalation to adjustment according to changes in the consumer price index for the local

market area. In these types of agreements, the lease is analogous to a long-term bond. In this scenario, the

lessor accepts a fairly secure and certain return on his investment in exchange for the potential risk that the

rent will fall behind market rent over the term of the lease.

The value of the interest is the sum of the present value of the net operating income during the term of the

lease and the present value of the reversion at the end of the lease. Let’s consider a typical build-to-suit

scenario where a prominent national tenant acquires land, builds a commercial building to their

specifications, and sells the building upon completion to an investor. The investor then enters into a long-

term lease agreement with a tenant (i.e., Wal-Mart, Home Depot, Rona, etc.). In these scenarios, the goal

of the national tenant is to control all aspects of the construction and site planning process but not have their

capital tied in the ownership of the property. The provisions for reversion of the lessee’s improvements at

the end of the term are an important consideration.

Chapter 6

6.4

Let’s assume that the Royal Bank enters into an agreement with a developer as follows.

• Developer selects site which meets bank’s retail banking location requirements.

• Developer acquires property and builds a retail bank according to Royal Bank’s specifications.

• Royal Bank signs a lease with the developer for a 30-year term, with 5-year rent reviews. Rent is

established at the greater of market rent or the rent in the last year of the preceding term.

• The bank building may or may not have remaining economic life at the end of the term. If the lease

has a clause which requires removal of the improvements and sub-structures at the option of the

lessor at the end of the term, the lessee may have a negative reversionary value related to this future

liability.

A practical example of the reversion issue is a build-to-suit leased Royal Bank building located across from

the Richmond Centre Shopping Centre in Richmond, BC. The bank is designed as a typical two-storey retail

bank, with a large surface parking lot on a prime corner. When the bank was first constructed, the general

area was improved with a mix of older single-family housing and strip malls. In 2009 the Canada Line

(Skytrain) was extended from Vancouver into Richmond with the Richmond line terminus located across the

street from the Bank. Over the passage of time, the houses have disappeared, strip malls have been

converted to modern neighbourhood plazas with national brand retailers, and mixed-use projects are

common. The highest and best use of the property is likely a much higher commercial density, perhaps a

multi-storey condo and ground level commercial units. In this scenario, the owner may receive offers to sell

the property which exceed the leased fee value.

Our main point with this example is to be very cautious when dealing with reversions. Ensure you have a

firm basis for assigning value to an asset where the value will only be realized in the long-term. It’s difficult

for any analyst to reliably forecast market conditions for 6 months. You may be attempting to forecast

market conditions 20 or 30 years in the future!

Leasehold Estate

The leasehold estate is the right held by the lessee to use and occupy real estate for a stated term and under

the conditions specified in the lease. The leasehold estate is the complement of the leased fee estate held by

the landlord in that the value of the fee simple interest in the property would consist of the sum of the value

of the leased fee interest, plus the value of the leasehold interest.

Similar to the leased fee estate, a leasehold estate is a partial estate that exists only during the term of the

lease. When valued, the interest is known as the “value of the leasehold estate” or lessee’s interest.

The value of a leasehold estate is the difference in the present value between market rent and contract rent

(i.e., the excess rent, assuming market rent exceeds contract rent) for the remainder of the term, including

the value of all rent incentives provided by the landlord (e.g., free rent period, fixturing allowance, etc.).

A simple example of a leasehold interest is a retail tenant who operates a drug store in a strip mall. The

tenant has secured a lease for 5,000 sq. ft.

with a 10-year term at a fixed rate of $20.00 psf, escalating to

$22.00 psf in year 6 of the term. By year 3 of the lease, market rents for similar space have increased to

$23.00 psf. Given positive market conditions it is possible that rents will continue to rise. The tenant has a

minimum $3.00 psf rent advantage for years 3 to possibly year 5 and beyond, amounting to a minimum

rental advantage of $15,000 in rent per year for at least 3 years.

The difficulty is forecasting continued strength in the retail market for periods greater than the short-term.

The other issue is that the tenant can only realize their potential leasehold interest by an assignment to

another party who is prepared to pay a fee for the right to obtain a below market lease, or enter into a sub-

Valuation of Leasehold Interests

6.5

lease at market rent. Landlords are well aware of this possibility and most will ensure that the lease has a

provision to restrict the ability of a tenant to sub-lease or assign their interest for a profit.

Sublessee’s Interest

When the tenant or lessee subleases to a third party, a further interest is created in the property. The person

to whom the sublease is given is known as the sublessee and the sublessee’s interest is known as the sub or

top leasehold estate. This estate exists only during the term of the sublease. The original lessee now becomes

known as the head lessee as well as the sublessor. The term of a sublease is typically equivalent to the

remaining term of the head lease, less 1 day.

The sublessee’s interest is the right conveyed by the lessee for the use and occupancy of a property to

another party, the sublessee, for a specific period of time which may or may not terminate with the

underlying lease term.

The value of the subleasehold or sublessee’s interest is found by calculating the present value of the

difference between the market rent and the contract rent paid to the head lessee or sublessor for the

unexpired term of the sublease. The sublessee’s interest is instantly “crystallized” or realized when the

sublease is executed by the parties for an amount less than market rent.

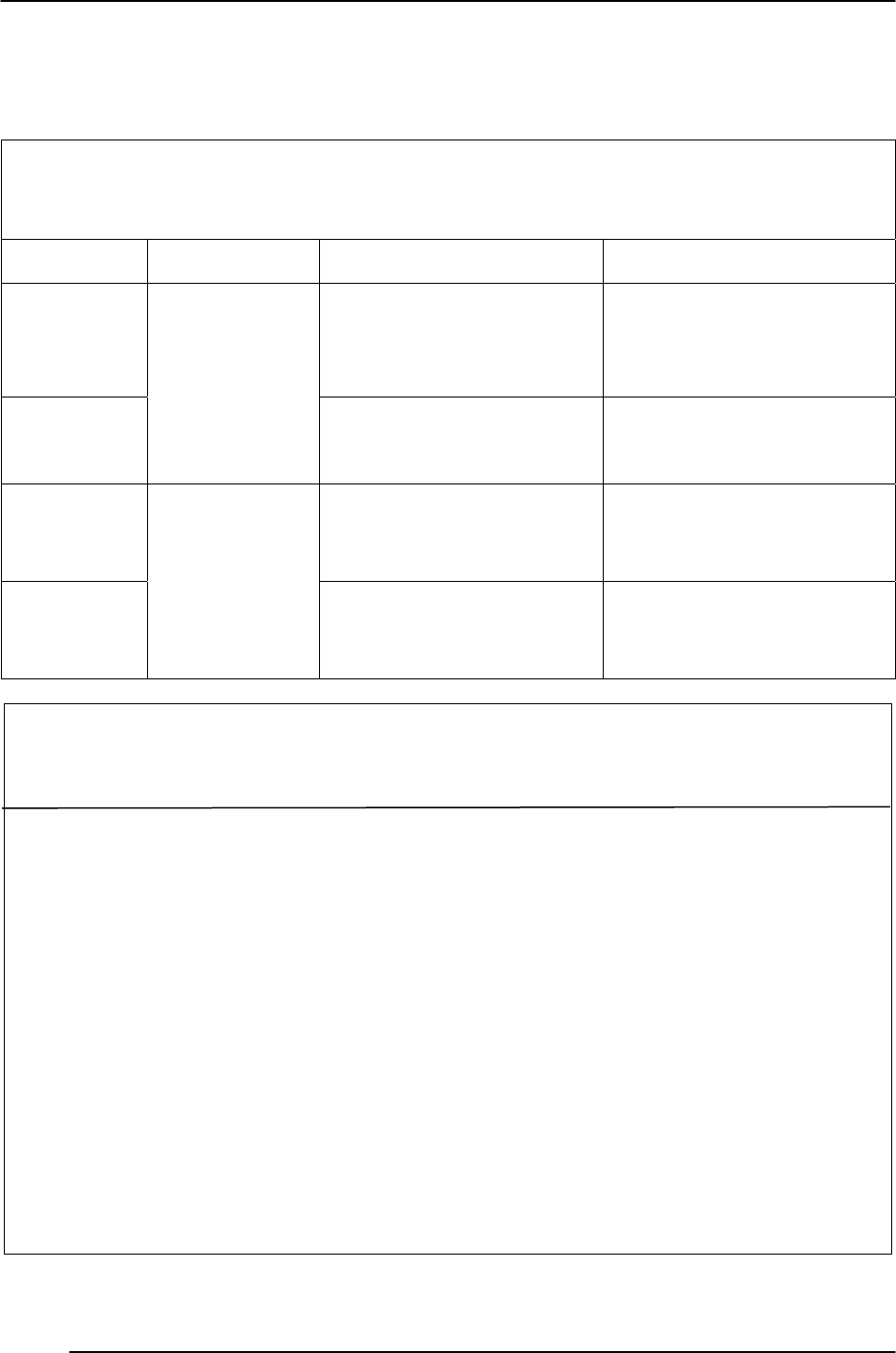

Figure 6.1

Property Interests Involving Leasing

Fee Simple Owner

Grants a lease and becomes

Landlord

Lessor

Leased Fee Owner

Tenant

Lessee

Leasehold Estate Owner

Grants a sublease and becomes

Sublessor

Sublessor’s Interest Owner

Subtenant

Sublessee

Subleasehold Interest Owner

Chapter 6

6.6

What Creates Leasehold Value

There are two general methods by which leasehold value is created.

Change in market conditions

Leasehold value may be created when the contract rent is less than the current market rent. There are

limitations to this theory, the most important being the right of the lessee to assign or sublease their lease to

a third party at market or above contract rent to realize the rent differential. The second limitation is the

length of term remaining in the lease – it may be of insufficient length to create value. The third condition is

that the lessee has the ability to wind up their use of the existing premises. If the lessee still needs the

premises for their activities, there is little point in assigning or subleasing their space since the lessee will be

back competing for new space at market rent.

The reality is a leasehold interest rarely has value since tenants will need compelling reasons to assign or

sublease their premises. Typically, an assignment or sublease will be necessary as a result of the tenant’s

business failure, need for less or more space, disagreements with the landlord, merger and acquisitions, or

another business issue. In other words, it is business events that trigger the need to assign or sublease, rather

than an opportunity to realize a profit related to below-market rents.

In the event a lease does permit a sublease, it seems intuitive that a lease

term with 12 remaining years has more value than a lease with a remaining

term of 3 years. Note, however, that many leases contain a clause relating to

subletting that specifies that any increase in rent above the contract rent

(i.e., excess rent) as specified in the original lease, resulting from a sublease

agreement, shall accrue to the landlord. This provision eliminates any

potential leasehold value.

Capital investment by the lessee

Leasehold value may be created when the lessee constructs a new leasehold improvement or when he or she

makes a substantial investment in remodelling or rehabilitating an existing structure.

Common examples of capital investment scenarios are land or ground leases involving national brand

retailers who negotiated sale leaseback arrangements with developers to construct build-to-suit specialized

improvements. Home Depot, Rona, Canadian Tire, Wal-Mart, and various Quick Service Restaurants use

this business model to avoid tying up large amounts of capital in real estate. An early adopter of this

business model was McDonalds Restaurants. McDonalds would typically secure land leases in prime

commercial locations, and then sub-lease to local entrepreneurs as part of the franchise agreement.

McDonalds would then finance the local franchisee who would construct and operate the chain restaurant

according to McDonalds’ specifications.

Valuation Methods

The appropriate valuation approach will depend on the interest being appraised and whether a market value

or investment value or pro forma analysis is sought by the client. In contrast to market value, investment

value represents value to a specific investor, not necessarily value to a typical investor in the marketplace.

What creates leasehold

value?

1. change in market

conditions

2. capital investment

by the lessee

Valuation of Leasehold Interests

6.7

Clearly, the first step in any consulting or valuation assignment is to clearly understand what type of advice

the client requires. Let’s assume that a lessee believes they have a valuable leasehold interest. They want to

demonstrate to a lender, with independent advice, that value exists in the leasehold and that this value can be

security for a business loan. Enter the appraiser, you. The assignment is to provide an estimate of the market

value of the leasehold interest. This involves all the steps and due diligence that an appraiser would

undertake for any other type of valuation assignment, including market research. In this example, we would

expect you to include in your report, at a minimum, the following:

• the contract rent, net effective rent, and market rent;

• the number of years and months remaining in the term of the lease;

• treatment of landlord and tenant improvements upon expiry of the term (the reversion);

• whether the lease permits the tenant to realize any short-fall between contract and market rent; and

• the investment horizon for the analysis.

The term net effective rent or NER is used by real estate professionals to pinpoint the actual cash inflow

resulting from a lease agreement. NER is also referred to as Common Net Effective Rent. Landlord

incentives such as free rent, tenant improvement allowances, and other tangible benefits have the effect of

reducing the contract rent to an effective rent. REALpac defines Common Net Effective Rent as follows.

Common Net Effective Rent is the true Rent related to a certain lease transaction, based on the

present value using the common discount rate, of all Rent receivable by a Landlord over the

initial fixed term, less the present value of all tenant inducements, free rent periods and

commissions payable, with such remainder present value then amortized over the fixed initial

lease term (REALpac/AIC 2001).

NER or Common NER is commonly used by brokers, landlords, and tenants to compare the impact of

alternative leasing incentives, terms, and other lease modifications over the term. NER is also very useful

for tenants in comparing the economics of alternative space for lease and provides the landlords the ability to

determine if they are competitive in the local market.

Consider the following simple example of this concept. Assume that a landlord has negotiated lease renewal

terms with a lessee and wants to know the common effective rent for the term. The details of the lease

renewal are as follows.

Term: 5 years

Rentable Area: 2,500 square feet with the lessee having the option to expand to 3,500 sq.ft. in

year 3

Contract Rent: $15.00 psf for years 1-3, escalating to $16.00 psf for years 4-5

Free Rent: 3 months of free rent in year 1

TI Allowance: $10.00 psf to be provided at the end of year 1.

Rent is payable monthly, in advance.

A simple, non-discounted cash flow analysis is provided below, based on two possible scenarios: no change

to rentable area and, secondly, an expansion of rentable area to 3,500 sq.ft., as noted above.

Chapter 6

6.8

Common Net Effective Rent - Scenario 1 No Change to Size

Year

Contract

Rent psf

Rentable

Area

sq. ft.

Total Contract

Rent

Incentives

Common

NER

1 $15.00 2,500 $37,500.00 $9,375.00 $28,125.00

2 $15.00 2,500 $37,500.00 $25,000.00 $12,500.00

3 $15.00 2,500 $37,500.00 $0.00 $37,500.00

4 $16.00 2,500 $40,000.00 $0.00 $40,000.00

5 $16.00 2,500 $40,000.00 $0.00 $40,000.00

Totals $192,500.00 $34,375.00 $158,125.00 psf

Average Common NER over the Term $31,625.00 $12.65

Common Net Effective Rent - Scenario 2 Size Increased in YR 3

Year

Contract

Rent psf

Rentable

Area

sq. ft.

Total

Contract

Rent

Incentives

Common

NER

Common

NER psf

% of Total

Rentable

sq. ft.

psf

1 $15.00 2,500 $37,500.00 $9,375.00 $28,125.00 $11.25 16.13% $1.81

2 $15.00 2,500 $37,500.00 $25,000.00 $12,500.00 $5.00 16.13% $0.81

3 $15.00 3,500 $52,500.00 $0.00 $52,500.00 $15.00 22.58% $3.39

4 $16.00 3,500 $56,000.00 $0.00 $56,000.00 $16.00 22.58% $3.61

5 $16.00 3,500 $56,000.00 $0.00 $56,000.00 $16.00 22.58% $3.61

Totals 15,500 $239,500.00 $34,375.00 $205,125.00 100.00% $13.23

Average Common NER over the Term $41,025.00

Weighted Average Common NER psf $13.23

This analysis would assist the landlord in understanding the impact of any front-end incentives on the overall

value of the income stream associated with this tenant. Notice that the combined impact of the expanded

space in year 3 and landlord incentives in year 1 and year 2 of the lease (based on the original, smaller

space) leads to an increased NER psf over scenario 1 (no increase in leased space), since the cost of the

landlord inducements are spread over a larger area.

Valuation of Leasehold Interests

6.9

In this simplified example we have not accounted for the impact of time. Later in this lesson we will provide

examples of discounting techniques that can be used to determine the present value of the common net

effective rent.

The most common methods of valuation for various interests related to leased properties will be direct or

overall capitalization using the simple annuity approach, or discounted cash flow analysis. The goal is to

determine the present value of the income stream, plus present value of any reversion at the end of the term.

In the next section of this chapter we provide examples of the application of both methods.

Overall/Direct Capitalization Method

Fee Simple Interest

The fee simple interest is most commonly determined through the overall or direct capitalization method

from comparable sales.

The first step in the process, once the highest and best use has been determined, is to determine market rent

for all leased space in the property, along with market rates of vacancy, and market capitalization rates.

Since this process should be well understood by students given earlier appraisal course material, we will turn

our attention to the real estate interests, discussed earlier.

Leased Fee Interest

A leased fee valuation is analogous to a landlord’s or owner’s investment analysis.

The value of the leased fee interest is represented by the present value of the contract rental income from

the lease(s) during the term(s) of the lease(s), plus the value of the reversion at the end of the term. Note

that market rents are applied to vacant space, owner occupied space, and space leased on a month-to-month

basis (periodic tenancies) and added to the rents from the leased space, to arrive at potential gross income.

To value a leased fee interest you need to answer the following questions.

1. What is the schedule for payment of contract rent?

2. What is the owner’s investment horizon? This period of time will likely be equivalent to the term of

the lease. The number of years left in the term at the valuation date is critical. For example, in a

scenario where only a few years are left in the term, a hypothetical leased fee interest may exist, but

the reality is that the market will largely discount the advantage or disadvantage to either party.

3. Is it likely that the tenant will continue to make rent payments on schedule for the remainder of the

term? An example of a tenant that may be at risk to not survive the term is a video rental store,

given the general business difficulty this category of retail tenant faces due to technological changes.

4. Are the lease terms representative of market leases for similar properties? An example of a unique

condition that favours the landlord and may enhance the value of the leased fee would be the

landlord’s right to charge additional percentage rent if the gross sales of the tenant exceed a stated

threshold, especially if there is evidence that the tenant’s business is growing.

5. Is the leased fee transferable? In rare cases there may be restrictions on the sale of the leased fee,

or a tenant may have a right of early termination.

Chapter 6

6.10

6. What reasonable market-based assumptions must be applied to forecast the future value of the

reversion (at the end of the investment horizon)?

7. What is an appropriate discount rate(s) to convert the future value of the net income from the leased

fee and reversion to present value?

One of the most difficult and problematic aspects of a leased fee valuation is the treatment of the reversion.

Should the analyst assume the property will increase in value over the investment period term according to

long-term trends in real estate inflation, or make a conservative assumption that the reversion will be

equivalent to the present value of the property? Should the going-in capitalization rate be higher, lower, or

the same as the terminal capitalization rate (applied to the reversion)? There is no universal answer to these

questions other than you need a basis for your assumptions to produce a credible outcome.

Leasehold Interest

In contrast to the leased fee valuation, the leasehold valuation represents tenant’s investment analysis.

In the valuation of the leasehold interest we need to answer the following questions, some of which are

similar to the leased fee analysis presented earlier.

1. What is the term of the lease and schedule for payment of contract rent? What is market rent for the

equivalent space?

2. Is it likely that the tenant will continue to meet the rent payments on schedule? As in the case of the

leased fee interest, there may be only a few years left in the term of the lease and little opportunity

for either party to gain an advantage.

3. Are the lease terms representative of commercial leases for similar properties? An example of a

non-typical condition which creates leasehold value is negative rent escalation. This type of

reduction in rent over the term is rare but may be offered by the landlord as an incentive to secure a

very desirable anchor tenant.

4. Is the leasehold interest transferable? There may be restrictions on the tenant’s right to assign or

sub-lease their lease. In some cases, the lease may contain a clause allowing the landlord to receive

any surplus rent that may be attributable to a lease assignment or sub-lease.

5. What is an appropriate discount rate to convert the future annual value of net cash benefits

associated with the leasehold interest to present value? The provisions for rent payment, e.g.,

monthly in advance, must be confirmed before selecting the correct discounting approach for the

periodic payments.

6. Will the reversion of the leasehold have a market value? Is the tenant required to remove the

leasehold improvements at the end of the term? An example would be a commercial building on

leased land where the building has remaining economic life. If this scenario exists, what is the

appropriate discount rate to convert the future value of the reversion to the present value? As we

learned earlier, the highest and best use of the property will drive whether significant leasehold

improvements, such as a commercial building, have a potential future reversionary value.

Valuation of Leasehold Interests

6.11

Here is a simple illustration of the concept of leasehold interest.

In 2000, a tenant leased a commercial lot at the corner of Arbutus Street and Broadway in Vancouver for a

term of 45 years with an initial rate of $6.00 psf. The tenant has constructed a retail store and leased the

premises to Rogers Communications (cell phone store) and a dry cleaners. Rent is adjusted every 5 years

according to the average annual change in the All-Items Consumer Price Index for Vancouver. By January

1, 2010, the CPI adjusted contract rent has escalated to $7.50 psf but the market rent is $10.00 psf.

Therefore, the value of the leasehold interest at Jan.1, 2010 is a minimum of $2.50 psf, not including the

potential for further gains as real estate inflation continues to outpace CPI and the present value of the

reversion at the end of term (if any).

The preceding example confirms that we must look beyond a single year’s income to determine the market

value of a leasehold interest.

In the next section, we will examine the practical application of discounted cash flow methods.

Yield Capitalization Discounted Cash-Flow Methods

Discounted Cash Flow or DCF methods allow consideration of multiple years of dissimilar income flow for

a property, permitting the analyst to apply more realistic assumptions about lease renewals and market

changes. It also permits more direct sensitivity analysis to test these assumptions.

Market rents are assumed in the case of the fee simple valuation, while contract rents with escalation factors

are assumed for valuation of the leased fee interest. In both cases, additional assumptions are required for

the investment horizon, trends in vacancy rates, and operating costs.

As discussed in Chapter 5, there are multiple approaches to determining discount rates for leased fee and fee

simple valuation: market derived, built-up, or band of investment. Terminal capitalization rates to be applied

to the reversionary interest at the end of the lease term must be determined in a consistent manner. The

analysis of sales of income producing properties will be based on contract rents at the time of sale for leased

fee valuations, while market rents will be applied to sales for fee simple analysis.

One aspect of DCF analysis that can be very difficult for appraisers is the treatment of the reversion. In our

earlier discussion of the valuation of leasehold estates, a major investment by a lessee invites a series of

questions: what is the economic life of the improvements; will the lessee be required to remove the

improvements at the end of the term; how does the economic life of the improvement relate to the highest

and best use of the property?

Ground leases with significant commercial investments tend to have very long terms with rights of renewal

in order to provide the long-term security necessary to finance the investment. Consider two very different

reversionary value scenarios:

1) In a stable neighbourhood, a lessor may be quite happy to receive a secure, long-term rent for land,

with Consumer Price Index escalation provisions with the rent analogous to income from a long-

term bond. Assuming rights of renewal, the value of the reversion would be the final year of income

capitalized at the terminal capitalization rate, discounted to current value. OR

2) In a neighbourhood in transition to high density commercial and residential use, the property may be

ripe for re-development well before the end of the lease term. Assuming no renewal provisions, a

prudent landlord would avoid offering a new lease and either sell or re-develop the property. The

lessee would have a liability to remove the buildings or more likely pay a negotiated settlement to

the lessor. In this case the reversion would have a negative present value to the lessee.

Chapter 6

6.12

The previous scenarios are gross simplifications. In reality, each lease will have unique provisions for

reversion and may be quite complex including options to purchase and/or early termination by either party.

Detailed examination is necessary to avoid a fatal error in determining the present value of the reversion.

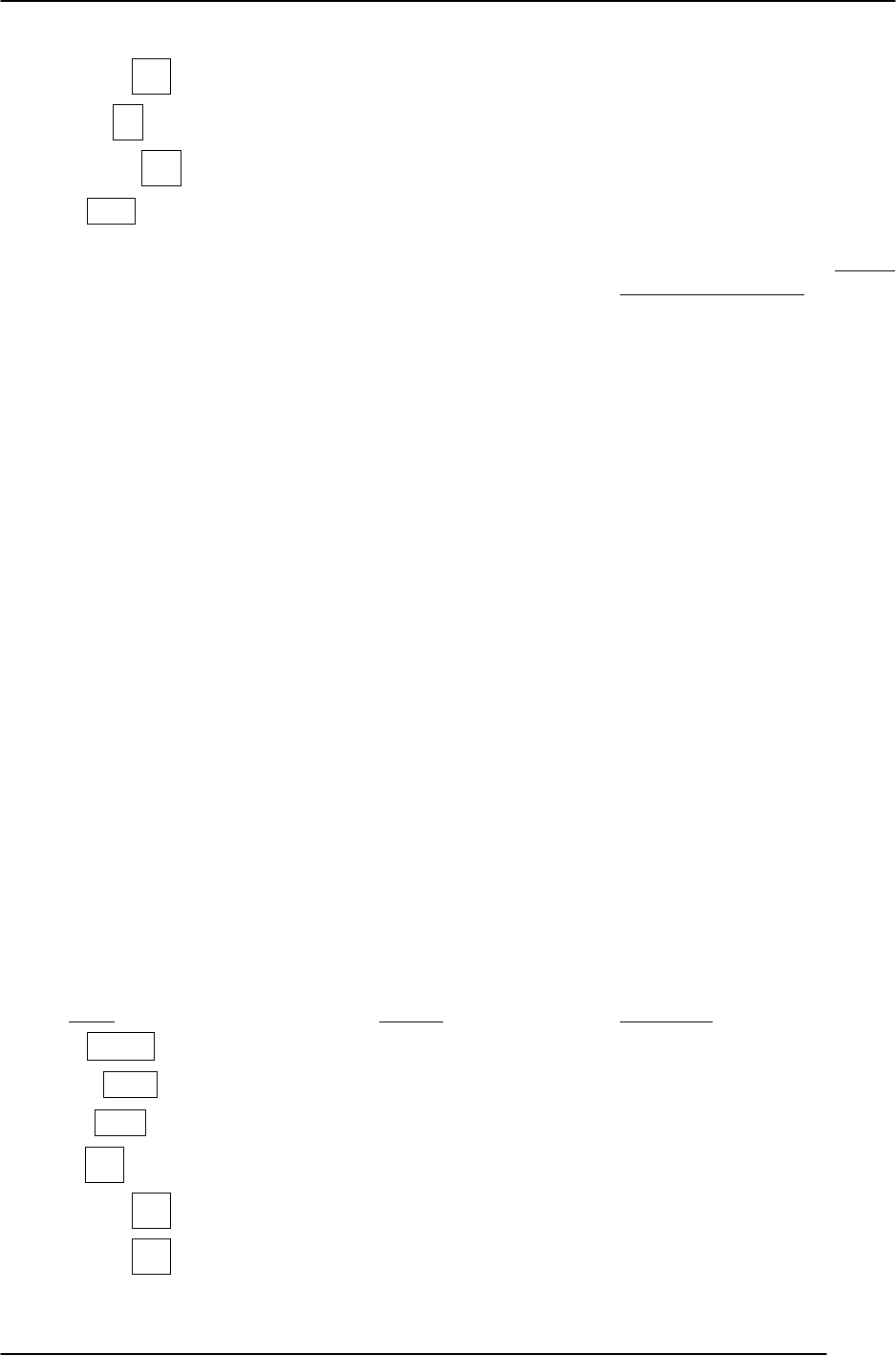

Figure 6.2

Summary of Income Valuation Methods

(Ignoring the Reversionary Value)

Interest Method Treatment of Income Capitalization Rate

Fee Simple

Overall

Capitalization

Current market rent applied to

all space in building, including

vacant space, up to market

occupancy levels.

Estimated from sales of similar

properties with market rents

applied to estimate income.

Leased Fee

Current or present value of

contract rent over the term for

all leased space.

Estimated from sales of similar

properties based on actual

income at the time of sale.

Fee Simple

Discounted Cash-

Flow

Market rent with step-ups over

investment horizon if

applicable.

Multiple options for Discount

Rate. Terminal Cap Rates

derived from market, reflecting

market rents.

Leased Fee

Contract rent applied for term

of each lease with assumptions

for escalation over investment

horizon.

Multiple options for Discount

Rate. Terminal Cap Rates

derived from market, reflecting

contract rents.

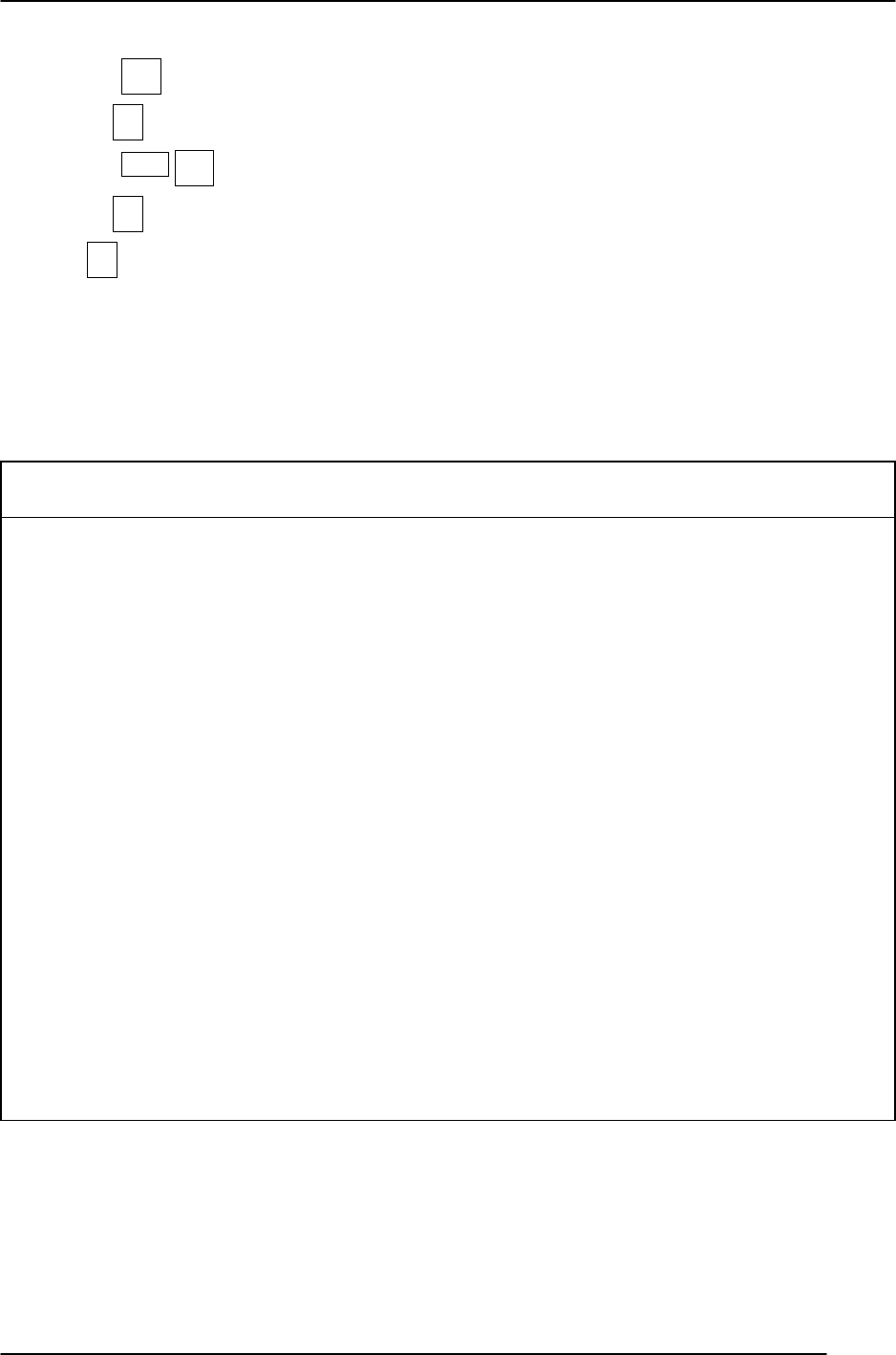

Figure 6.3

Summary of Incomes and Reversions Associated with Various Real Property Interests in

Income-Producing Property

Fee Simple

Income Net operating income based on market rents (NOI or I

O

)

Reversion Net proceeds of disposition (REV

N

or V

N

)

Leased fee

Income Net operating income based on contract rents

Reversion Property reversion or net proceeds of disposition of leased fee estate

Leasehold

Income Rental advantage when contract rent is below market rent; rental

disadvantage when contract rent is above market rent

Reversion None if held to end of lease or net proceeds of resale of leasehold

estate; could be negative if lessee is responsible to restore the property

(demolish tenant improvements, or building for a ground lease)

Source: Table is adapted from Table 20.3 in Appraisal of Real Estate (3

rd

Canadian Edition). Vancouver: UBC Real Estate Division

Valuation of Leasehold Interests

6.13

Valuation of All Interests

In rare cases you may be asked by a client to produce separate estimates for each interest in the property: fee

simple, leased fee, and leasehold interest. This scenario may arise where an owner intends to sell or seek

venture financing and wishes to provide evidence of the additional potential value attributable to below

market leases. The premise is that a purchaser would have significant rental ‘up-side’ when leases roll-over

at the end of various terms.

To prepare a separate valuation of each interest the steps are as follows:

1. Estimate the market value of the property as though free and clear of the leases by the three

approaches to value. The income approach will likely be found to be the best valuation test and will

be given the greatest consideration in the reconciliation. As we illustrated earlier in this chapter,

market rent, rather than contract rent is applied. The estimated market value of the property should

equal the sum of the lease interests, unless contract rents are higher (i.e., excess rent) or lower than

the market rent. In the case where excess rent applies, total value of the lease interests will be

higher than the market value estimate. This situation is referred to as the “two property concept“,

and is explained in further detail in a later section.

2. Allocate the rents to the different interests, select the appropriate capitalization rates and method

of capitalization. The rates selected for application to the different interests may vary as explained

later in the course. In addition, because leases have the aspects of annuity incomes, the Inwood

Premise of capitalization will often be found to be the most appropriate method. (Inwood accounts

for both the return on investment plus a sinking fund to account for the return of the investment over

the investment period, effectively accounting for the assumption that there is no reversionary value

at the end of the lease term. Inwood is discussed in detail in Chapter 9.)

3. Estimate the present value (PV) of the leased fee owner’s interest which includes the present

value of the income stream plus the present value of the reversion (if a reversion is significant in the

situation).

4. Estimate the present value (PV) of the leasehold interest, being those of the lessee and sub-

lessee, if any. Such interests are determined by finding the present value of the difference between

the market rent and the contract rents at the date of the appraisal.

5. Find the sum of the present values (PVs) of the different interests. If this sum total is at great

variance with the initial market value estimate, as if free and clear, the entire process should be

reconsidered, with the original market value estimate being reviewed and the capitalization rates and

discount rates applied to the different interests also being reviewed. Unless there are excess rents,

the value of the sum of the parts (various interests created by leases) generally cannot exceed the

value of the whole (fee simple).

Selection of Discount Rates for Various Interests

When capitalizing the income streams attributable to the different interests, it is reasonable, in many

situations, to assume that the risk varies according to the position of the interest. This is, to a degree,

somewhat like the assumptions made in finance’s Band of Investment Theory (reviewed in Chapter 9) of

selecting an interest rate where a first mortgage was considered to have less risk than a second mortgage or

equity position. The first, and least risky position, is that of the leased fee or the fee simple owner when the

contract rent is no higher, and possibly lower, than the market rent. When the contract rent is greater

Chapter 6

6.14

than the market rent, the portion that can be considered, therefore, as “excess rent”, may be thought

to have more risk than the market portion and it could be capitalized separately at a higher rate.

However, if the higher contract rent is well-supported by a financially secure AAA tenant, it may be

considered that the contract rent in excess of the market rent presents no real extra risk.

The second position, with somewhat more risk, is that of the leasehold which is caused by the market being

greater than the contract rent. The excess income stream attributable to the leasehold may be assumed to

carry greater risk and should be capitalized at a rate higher than that applied to the leased fee interest. This

is a situation similar to interest rates for first and second mortgages. Second mortgage rates are almost

invariably higher than first mortgage rates because of the riskier position.

The third position, with the greatest risk, would be that of a lessee (i.e., head lessee) who in turn sub-leases

the property. This position is thought by some appraisers to have a greater risk than the second or first

position and a higher capitalization or discount rate may be applied to this income stream. For example, a

typical office sub-lease will only extend for the remaining years in the term or a much shorter period. Since

the sub-lessee will typically have no rights of renewal, both parties appreciate the short-term nature of the

arrangement. This means that the sub-lessee may “bolt” before the expiry of the sub-lease if their business

fails or more favourable space is secured elsewhere.

In contrast, long-term sub-leasing scenarios commonly occur on First Nations reserves, Airport Authority

lands, and other Crown lands. Other examples are build-to-suit arrangements involving large industrial

operators or high profile retailers. In these cases a developer initially leases undeveloped or unserviced land,

creates a commercial or industrial project, and sub-leases the property to one or more sub-lessees for a term

of 1 day less than the original or head lease, or a term sufficient to recover the developer’s investment.

Illustrations of Market and Contract Rents

The following problems will demonstrate the application of lease analysis and valuation.

Long Term Ground Leases

It is not uncommon, particularly in an inflationary market, to find that the market rent is higher than the

contract rent when analysing leases in a particular property. With a market rent higher than the contract

rent, the lessee (tenant) may have a leasehold interest which perhaps can be continued, subleased, or sold.

The opposite

is often true in a declining or soft market. In such a circumstance, both the lessor and the

lessee can demonstrate they have a financial interest in the same property.

For example, consider the following ground lease. Assume that Harry, the fee simple owner of a vacant

commercial property, leased it fifteen years ago to John for a 40-year lease term and annual rent of $30,000

on a fully net basis. We will refer Harry’s lease to John as the head lease to clearly distinguish it from one

or more subleases.

Ten years ago the land value had increased to the point that the then market rent for the head lease was

reasonably estimated at $45,000 on the same terms and conditions. If we also assume that John subleased to

Maria ten years ago at the market rent at that time of $45,000 per annum and the market rent now is

estimated to be $50,000 per annum, all three parties could have a financial interest in the property.

Remember, this depends on the wording of the lease.

Valuation of Leasehold Interests

6.15

The illustration of the rights to receive rent from all three parties is as follows:

(a) Lessor (Leased Fee), or Harry’s interest, is based on the fee owner, Harry, being entitled to receive

the contract rent of $30,000 per annum for the remaining 25 years of the head lease and the right to

have the parcel of land revert back to him free and clear of the lease at the end of the term of the

lease.

In other words, the value of Harry’s interest is the present value of the income stream of $30,000

plus the present value of the reversion, both discounted at an appropriate rate to reflect the security

of the Leased Fee interest.

(b) Lessee’s (Leasehold Estate) Interest, or John’s interest, is the difference between contract rent for

the head lease and market rent at time of the sublease.

Market Rent 10 years ago $45,000

Contract rent paid to Lessor under original lease $30,000

John’s Rent advantage $15,000

The value of the Leasehold Estate is the present value of the rent advantage for the remainder of the

lease, in other words 25 years, discounted at an appropriate rate that reflects the risk of the Lessee’s

(John’s) position as a Sublessor.

(c) Sublessee’s (Subleasehold Estate) Interest, or Maria’s interest is the difference between the current

market rent and the rent she pays to John under the terms of the sublease.

Current Market Rent $50,000

Contract rent paid under the sublease to John $45,000

Maria’s rent advantage $ 5,000

The value of the Subleasehold estate is the present value of the rent advantage of $5,000 for the

remaining 25 years of the lease, discounted at a rate that reflects the risk of this position.

In the event the contract rent for the head lease is equal to or greater than the market rent, the lessee (John)

and sublessee (Maria) would have no interest. Moreover, if the contract rent exceeds current market rent, an

excess rent would exist. This scenario is likely a significant risk for Harry since the lessee would object to

paying above market rent and the contractual requirement to continue to this level of rent may result in

financial or business difficulties for the lessee, John, resulting in a potential rent default. If Harry tries to

sell his leased fee interest, most investors would attribute less than full value to the excess rent given the

above noted risks.

We will now use the information to illustrate how the rights to rental can be estimated for various interests

in a property to carry out the actual valuation of each separate interest.

(a) Estimated market value of land (fee simple) by direct comparison approach: $650,000

(b) Allocation of current market rents to the different interests, selection of rates and method of

capitalization. The original lease has 25 years left.

Interest

Rental Interest Selection of Rate

Harry $30,000 8%

John $15,000 9%

Maria $ 5,000 10%

Chapter 6

6.16

Notice how a higher discount rate was applied to leasehold and subleasehold interests versus the leased

fee interest. These rates reflect the hierarchy of risk premiums associated with interests which are less

than fee simple.

(c) Valuation of Fee Owner’s Leased Fee Interest (Harry’s Interest)

Present Value of future income for 25 years at 8% per annum, compounded annually in

advance.

Calculation

Press

Display Comments

■

C~ALL

0 Clear all registers

■

BEG/END

Begin

8

I/YR

8

1 ■

P/YR

1

30,000

PMT

30,000

650,000

FV

650,000

25

N

25

PV

-440,774.39

Present value of Fee Owner’s Interest is $440,774.39.

The future sale price of the property must be estimated by the appraiser to arrive at the

reversion. In this case, the appraiser is working under the assumption that the land will not

appreciate, meaning its market value is $650,000 today and will also be $650,000 25 years from

now. Whether or not this assumption is appropriate depends on the particular market in

question. Alternative assumptions regarding price changes over this time can be made, but

ideally should be supported in some way by market evidence. The problem for many appraisers

is that their assumptions about the future value of the reversion are not well founded. In these

cases the proceeding analysis becomes more of a black art than an economic science.

Mathematically, the longer the term, the less significance the reversion will have, because of

discounting.

1

(d)

Valuation of Leasehold Interest (Lessee John’s Interest)

Present Value of future income for 25 years at 9% per annum, compounded annually in

advance.

1

Now that we have determined a value of $440,774.39, we can investigate the sensitivity of our assumed stable reversion value. If instead we

assumed 2% annual growth in price ($650,000), the reversion would be $1,066,393.90. This revises our final answer to $501,575.35. If

instead we assumed a 2% annual depreciation in prices, say for a gravel pit that is declining in usefulness, then the reversion is $392,252.07

and the final answer $403,138.57. This highlights the importance of evaluating the impact of assumptions through sensitivity analysis.

Valuation of Leasehold Interests

6.17

Calculation

Press Display Comments

■

C ALL

0 Clear all registers

9

I/YR

9

1

■

P/YR

1

15,000

PMT

15,000

0

FV

0

25

N

25

PV

-160,599.176541

Present value of Leasehold Interest is $160,599.18.

(e)

Value of Subleasehold Interest (Sublessee Maria’s Interest)

Present Value of future income for 25 years at 10% per annum, compounded annually in

advance.

Calculation

Press Display Comments

■

C ALL

0 Clear all registers

10

I/YR

10

1

■

P/YR

1

5,000

PMT

5,000

0

FV

0

25

N

25

PV

-49,923.7201003

Present value of Subleasehold Interest is $49,923.72.

Leased Fee Interest (Harry) $440,774.39

Leasehold Interest (John) 160,599.18

Subleasehold Interest (Maria) + 49,923.72

Value of All Interests (Fee Simple Value) $651,297.29 (Rounded to $651,300.00)

You will note that this example illustrates that the sum of all the interests is approximately the same as the

market value free and clear of the lease. It is important to observe the fact that the lessor’s interest, or the

leased fee, is very much affected by the terms of the lease and the contract rent received.

In a typical sales transaction, it is the leased fee estate that would be sold. On the other hand, in most

provinces, it is fee simple interest that is valued for the purposes of property tax assessment.

Chapter 6

6.18

In actual practice, the selection of rates for capitalizing the various interests would have been a major

consideration. If market data were available, then the rates would have been selected from the market as this

is the preferred method. If, however, as is often the case, sufficient market data is not always available, it

will be necessary to construct reasonable rates bearing in mind the rates of return on Government bonds,

prime industrial and trust certificates, mortgage rates, etc.

Improved Property Lease

The valuation of lease interests in an improved property is treated in a similar manner to that already

discussed with the difference being that if the building is assumed to have a remaining economic life in

excess of the balance of the term of the lease, its depreciated value will form part of the reversionary value

to the fee owner.

A property in the downtown section of your community is held on a triple net lease, having 15 years

remaining at a monthly rent of $6,500 payable at the beginning of each month (i.e., in advance).

The remaining economic life of the building is estimated at 30 years. Current market value of the improved

property in fee simple is estimated at $780,000 with land value well-substantiated by a market comparison at

$256,000. Estimate the value of both the lessor’s and lessee’s interest in the property assuming a discount

rate of 10% per annum, compounded monthly.

Solution:

Step 1:

Estimated Market Value (improved) $780,000

less: Land Value Estimate - 256,000

Building Value

$524,000

If the building has an economic life of 30 years and the lease has 15 years to run, then based on straight line

overall depreciation, 50% of the economic life will remain when the building reverts to the owner of the

land. Hence, in 15 years the value of the building reversion will be 50% of its current value, or $262,000.

Let’s assume that the land value at reversion will be equivalent to the present land value of $256,000.

Note that if additional money is spent on the building during the 15 years remaining on the lease, the life of

the building may be extended, which will require adjusting the reversion amounts. All of the foregoing are

simply estimates (remaining economic life and value in 15 years), but any errors in estimating the value of

the reversion will be minimized by the discounting process. In fact, if the holding period is long-term

enough, the present value of the reversion will often be so small as to be insignificant. In these cases, the

reversion can be omitted from the analysis. In practice, this part of the appraisal requires judgement and an

interpretation of trends.

Valuation of Leasehold Interests

6.19

Step 2: Lessor’s Interest (Leased Fee Interest)

Present value of monthly payments, $6,500 in advance, plus reversion, at end of 15 year period, discounted

at j

12=10%.

Calculation

Press Display Comments

■

C ALL

0 Clear all registers

■

BEG/END

0 Should see “Begin” on calculator

display screen indicating

payments in advance (at

beginning of period, as is typical

for a lease)

10

I/YR

10

12

■

P/YR

12

6,500

PMT

6,500

15 × 12 =

N

180

256000 + 262000 =

FV

518,000 Reversion consisting of land

value plus 50% of building.

PV

-726,216.019366

Present value rounded to $726,200.

Step 3: Lessee’s Interest (Leasehold Estate)

Value of real estate $780,000

l

ess: Lessor’s Interest (Leased Fee Estate) - 726,200

= Lessee’s Interest (Leasehold Estate)

$53,800

For illustration, we will also illustrate how the fee simple interest is the sum of all of the interests in the

property.

Step 4: Fee Simple Interest (Value of all interests)

Lessor’s Interest (Leased Fee Estate) $726,200

add: Lessee’s Interest (Leasehold Estate) + 53,800

= Fee Simple Interest (Value of all interests)

$780,000

Long Term Graduated Leases

A critical element in the valuation of any income stream is time, particularly in the valuation of graduated

leases. Leases of this nature generally provide for rent increases at specific periods during the term of the

lease. This is usual for longer term leases or for leases negotiated when increases in market rents are

anticipated.

Chapter 6

6.20

For example, assume a 15 year graduated lease which is to be capitalized or discounted at a rate of 9%.

The rent is paid annually in arrears

and the rent schedule is as follows:

1st 5 years $ 6,000 per annum

2nd 5 years $ 8,000 per annum

3rd 5 years $10,000 per annum

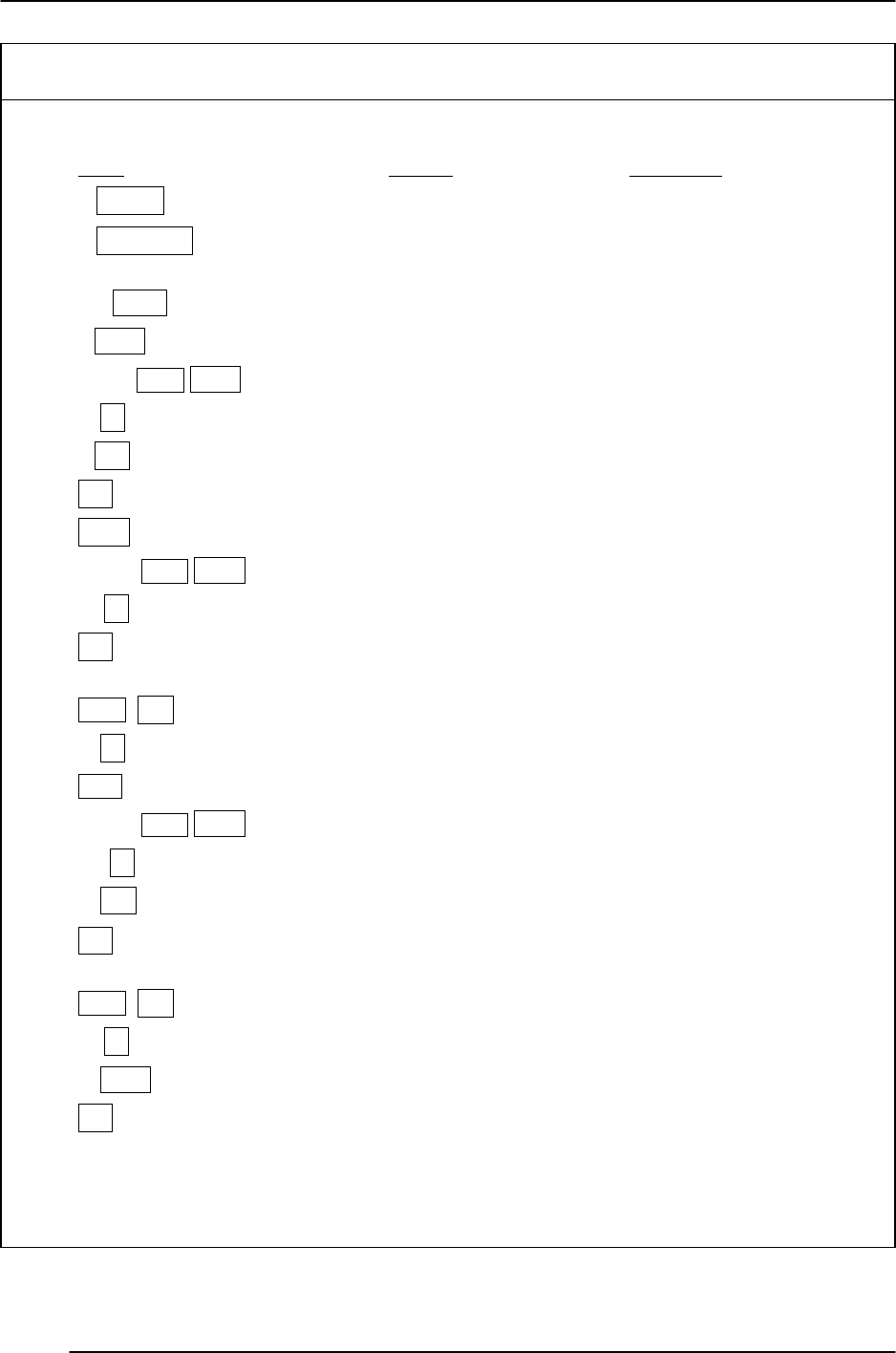

The lease can be illustrated by the following diagram:

Today End of Year End of Year 10 End of Year 15

Solution: Present Value of Fee Owner’s Interest

To find the value of the fee owner’s interest, you will have to calculate the present value of the lease payments.

Because the payments vary over the term of the lease, this calculation will be done using the cash flow keys

rather than the PMT key. Also, note that within the lease in this particular example, the lease payments are

made in arrears, as opposed to most leases where payments are made in advance. The reversion value for this

property, using the $10,000 lease payment in Year 15 and the 9% capitalization rate, is estimated to be

$111,111.

2

Calculation

Press Display Comments

■

C ALL

0 Clear all registers

1

■

P/YR

1

9

I/YR

9 Discount Rate

0

j

CF

0 No initial cash flow

6,000

j

CF

6,000 Year 1 lease payment (due at the end of

the first year)

5

■

j

N

5 Repeat 5 times (Years 1-5)

8,000

j

CF

8,000 Year 6 lease payment

5

■

j

N

5 Repeat 5 times (Years 6-10)

2

In using direct capitalization to calculate a reversion value at the end of Year 15, remember that you need to use the income from the end of Year

16. In this illustration, we have implicitly assumed that the $10,000 annual lease payment paid during the last 5 years of the lease term will remain

constant in Year 16.

$10,000/yr

$8,000/yr

$6,000/yr

Valuation of Leasehold Interests

6.21

10,000

j

CF

10,000 Year 11 lease payment

4

■

j

N

4 Repeat 4 times (Years 11-14)

10,000 + 111,111 =

j

CF

121,111 Year 15 lease payment plus reversion

value

■

NPV

90,496.4626779

Present Value = $90,496.46

The cash flow solution provides a present value based on the lease payments. The reversion of $111,111 is

received at the same time as the last income payment and they are added together for the final cash flow.

Extreme caution must be used when applying the cash flow method to make sure that the correct timing and

number of payments are entered. As well, make note as to whether payments are received at the end or at

the beginning of each period. The key to this is drawing an accurate time line (see the “Comprehensive

Lease Problem” for an example of this).

Note that if the payments were to be in advance (at the beginning of the period) rather than in arrears,

you would repeat the $6,000 lease payment only 4 times, enter the $111,111 reversion alone as the final

cash flow (at the end of Year 15), calculate the present value, and then add the initial $6,000 lease

payment received today. This would give a total present value of $95,895.77. For an illustration of

similar calculator steps, see how the present value of A’s Interest is calculated in the next example.

Comprehensive Lease Problem

“A” is the fee simple owner of a parcel of land. Ten years ago, “A” leased this parcel to “B” for 62 years at

the following rentals, payable in advance

:

Land lease:

Years 1-12: $8,000 per annum

Years 13-37: $14,000 per annum

Years 38-62: $20,000 per annum

Two years after leasing the parcel from “A”, “B” developed a small office building and leased it to “C” (the

sub-lessee). This lease runs for 60 years at the following rentals, again payable in advance

:

Building lease:

Years 1-15: $84,000 per annum

Years 16-35: $96,000 per annum

Years 36-60: $108,000 per annum

The market rent today, the date of the appraisal, is $100,000 per annum and the value of the land at the end

of the lease is estimated to be $200,000. The building will then have reached the end of its economic life.

What is today’s value of:

(a) “A’s” interest discounted at j

1 = 8%

(b) “B’s” interest discounted at j

1 = 10%

(c) “C’s” interest discounted at j

1 = 12%

Chapter 6

6.22

The time line below illustrates the timing of both the land lease and the building lease, as well as the

difference in payments (i.e., “B’s” interest).

Solution: A’s Interest

Present value of land rental plus PV of reversion income stream, noting that 10 years have gone by since the

lease was executed.

Present Value of Leased Fee - A’s Interest

Calculation

Press Display Comments

■

C ALL

0 Clear all registers

1

■

P/YR

1

8

I/YR

8 Discount Rate

0

j

CF

0

8,000

j

CF

8,000 Year 12 lease payment (due in

one year)

14,000

j

CF

14,000

25

■

j

N

25 Years 13-37

Valuation of Leasehold Interests

6.23

20,000

j

CF

20,000

25

■

j

N

25 Years 38-62

200,000

j

CF

200,000 Reversion value

■

NPV

178,305.010544

+ 8,000 = 186,305.010544 Year 11 lease payment (paid in

advance, so due today).

Present Value = $186,305.01

The cash flow solution provides a present value based on the land lease payments. The reversion of

$200,000 is received one year after the last income payment and is treated as the final cash flow. Extreme

caution must be used when using the cash flow method to make sure that the correct timing and number of

payments are entered. As well, make note as to whether payments are received at the end or at the beginning

of each period.

The key to this is drawing an accurate time line.

If the payments were to be in arrears (at end of period) rather than in advance, you would enter the

$8,000 cash flow twice, and add the reversionary value to the last year’s income from the final cash

flow.

Solution: B’s Interest (Capitalized value of difference between rent received and paid)

You will note that the rent B pays for land increases before the rent received increases. The balance of the

terms then coincide. The diagram should reflect that 8 years of premises lease have gone by plus 10 years of

land lease at the time of appraisal.

Present Value of Leasehold Estate - B’s Interest

You will note that

B receives income from the Building and also pays rent to A as an expense. In view of the

fact that the payments are both made in advance, it is possible to calculate a “net cash flow” for each period.

NOTE: If a problem is complicated in the way rents are paid and received with respect to payments in

advance and payments in arrears it is easier to (1) calculate a present value of the cash flows received

and (2) deduct the present value of the cash flow paid.

Calculation

Press Display Comments

■

C ALL

0 Clear all registers

1

■

P/YR

1

10

I/YR

10 Discount Rate

0

j

CF

0

76,000

j

CF

76,000 Year 12 Net Cash Flow

70,000

j

CF

70,000

Chapter 6

6.24

5 ■

j

N

5 Years 13-17

82,000

j

CF

82,000

20

■

j

N

20 Years 18-37

88,000

j

CF

88,000

25

■

j

N

25 Years 38-62

■

NPV

771,410.903211

+ 76,000 = 847,410.903211 Year 11 Net Cash Flow

Present Value = $847,410.90

Solution: C’s Interest

If the market rent for the building today is $100,000, and this is indicative of long

term rents, we can

compare the rent as paid under the lease to market rent to determine whether or not there is an advantage to

the tenant “C”.

“C’s” advantage is equal to the present value of the rental advantage where contract rent is lower than

market rent, less the present value of the rental disadvantage where contract rent is higher than present

market rent.

Present Value of Subleasehold Estate - C’s Interest

Calculation

Press Display Comments

■

C ALL

0 Clear all registers

1

■

P/YR

1

12

I/YR

12 Discount Rate

0

j

CF

0

16,000

j

CF

16,000 Rental Advantage (Years 2-7)

6

■

j

N

6

Valuation of Leasehold Interests

6.25

4,000

j

CF

4,000 Rental Advantage (Years 8-27)

20

■

j

N

20

8,000

/

+−

j

CF

-8,000 Rental Disadvantage (Yrs 28-52)

25

■

j

N

25

■

j

N

77,624.103451

+ 16,000 = 93,624.103451 Rental Advantage (Year 1)

Present Value = $93,624.10

The Present Value is positive, and thus indicates that the current tenant of the building, “C”, has an

advantage.

Calculating the Present Value of Monthly Cash Flows

Appraisal assignments often require present value analysis of leases with monthly rental payments. The

examples provided in this chapter show how to use the HP 10BII/10BII+ calculator to carry out this type

of calculation for leases with annual payments. The calculation for a lease with monthly payments uses the

same type of analysis, but students will notice that the number of payments is too large to use the HP

10BII’s cash flow keys whereas the new 10BII+ is capable of dealing with a large number of payments

with no limit on cashflows. When a series of cash flows are entered using the N

j key, using the 10BII,

there is a limit of 99 cash flows. There are several ways to approach this problem:

(1) the monthly lease payments could be multiplied by 12, giving annual payments which are easier to

work with. This method will result in an answer which is “close enough” for many appraisal

assignments. However, it is not completely accurate because it ignores the timing of the rental

payments within each year. As a result, it overstates the present value of these rental payments

(i.e., the present value of 12 monthly payments of $1,000 will be less than $12,000).

(2) the present value can be calculated using the NPV function and the CF

j and Nj keys. If there are

more than 99 cash flows required, say 10 years or 120 months, you could simply enter the given

cash flow with 99

■ Nj and then enter the cash flow again with 21 ■ Nj for the remaining cash

flows. For example, to enter 120 payments of $1,000, you would enter 1000 CF

j 99 ■ Nj and then

1000 CF

j 21 ■ Nj.

(3) the present value can be calculated using the PV and PMT keys to find the present value of each

series of cash flows separately, which can then be added together. The present value calculation

for the leased fee (A’s interest) from the previous example is shown below using this method:

continued

Chapter 6

6.26

Calculating the Present Value of Monthly Cash Flows (continued)

Calculation

Press Display Comments

■

C ALL

0 Clear all registers

■

BEG/END

0 Payments in advance (screen

should show “BEGIN”)

1

■

P/YR

1

8

I/YR

8 Discount Rate

8,000

/

+−

PMT

-8,000 Years 11-12 lease payments

2

N

2 Enter number of years

0

FV

0

PV

15,407.4074074 Present value of Years 11-12

M→

15,404.4074074 Store value in memory

14,000

/

+−

PMT

-14,000 Years 13-37 lease payments

25

N

25 Enter number of years

PV

161,402.615971 Present value of Years 13-37

(at the beginning of Year 13)

/

+−

FV

-161,402.615971 Enter as future value

2

N

2 Enter number of years

M+

138,376.72837 Add to value in memory

20,000

/

+−

PMT

-20,000 Years 38-62 lease payments

25

N

25 Enter number of years

0

FV

0

PV

230,575.165674 Present value of Years 38-62

(at the beginning of Year 38)

/

+−

FV

-230,575.165674 Enter as future value

27

N

27 Enter number of years

0

PMT

0

PV

28,864.9713792 Present value of $199,694.88

at the beginning of Year 11

(today)

continued

Valuation of Leasehold Interests

6.27

Calculating the Present Value of Monthly Cash Flows (continued)

M+

28,864.9713792 Add to value in memory

200,000

/

+−

FV

-200,000 Reversion value

52

N

52 Enter number of years

PV

3,655.90338737 Present value of reversion

today

M+

3,655.90338737 Add to value in memory

RM

186,305.010544 Total present value

Note that options (2) and (3) will calculate the exact same answer and either is acceptable.

Percentage Leases

A common scenario in leases for retail premises is the participation of the landlord in the success of the

lessee by levying rent based on a percentage of gross sales. The reason for the “sharing” is that in a retail

centre, the tenant mix is a key component to the success and viability of all the tenants. Percentage rent is a

way to encourage strong management and leasing. Percentage clauses can take many forms and the rate

payable can vary considerably from lease to lease within a given property. Listed below are some examples

The reason for basing percentage rents on gross sales, rather than gross profits, is that gross sales can be

consistently and readily determined while gross profit will vary considerably according to an owners

accounting practices and treatment of cost of goods sold.

Percentage Rent with No Minimum Rent

Rent is strictly based on a percentage of gross sales. This type of lease is extremely rare since there are no

performance guarantees for the landlord.

Percentage Rent Above Threshold Sales

In this type of lease the base rent is set based on market rents. The landlord then receives percentage rent for

all sales which exceed a specific benchmark or threshold, also known as the

breakpoint. In some cases the

threshold will escalate over the term of the lease, say a bump in year 5 from $2,000,000 in gross sales to

$2,400,000.

Greater of Percentage or Base Rent

This lease arrangement is similar to the percentage rent above threshold sales. However, in this case there is

no limit to the potential percentage rent which a tenant may pay. If the tenant has an exceptionally good

year, rent for the following year will be high since it is typically based on the prior year’s audited

statements.

Chapter 6

6.28

There may be variations on all these types of percentage leases. Trade organizations such as the

International Council of Shopping Centers and Urban Land Institute publish studies on typical percentage

rental rates associated with different types of retail businesses to assist parties in negotiating these

agreements. Retailers with low margins, such as food chain stores, tend to pay low percentage rents, in the

order of 1% to 1.5%, while fashion retailers, with much higher margins, may pay up to 5% to 7% of gross

sales.

3

A percentage lease will likely have detailed provisions which set out the definition of gross sales. For

example, gross sales will exclude HST, but include credit sales, sales made at other store locations, credit

card discounts, mail orders, trade-ins, gift certificates, and inter-store transactions. A generally acceptable

definition of gross sales is “the gross amount of all sales made in, from, or at the leased premises, whether

for cash or on credit, after deducting the sales price of any returned merchandise where a cash refund is

given.”

Percentage leases are much more difficult to handle than those with precise terms because the portion of rent

payable is dependent on gross sales. A number of economic and management factors will impact annual

gross sales. To determine whether the trend in percentage sales is upward, down, or stable it’s necessary to

examine several years of financials and understand the combined impact of local, regional, and global

influences on the tenant’s ability to succeed. For example, a change in store management, new competition

and changes in the attitudes of the buying public will affect sales. A combination of retail experience,

judgement and analysis is required by the analyst to arrive at a reasonable amount of percentage rent for the

capitalization process and an appropriate risk based discount rate.

The income generated through percentage rent certainly adds to the landlord’s bottom line, but the guarantee

that it will be maintained does not generally exist. Financial institutions and lenders will recognize the

existence of percentage rental income, but look to the minimum rents as the basis for lending. It is accepted

generally that the risk rate associated with the capitalization of percentage rental income may be higher than

the rate for guaranteed rent. However, this will vary upon the strength of the tenant and the length of time

percentage rent has actually been paid. If a consistent level of percentage rent has been maintained over a

number of years, there may be less risk with such a cash flow. Furthermore, landlords may negotiate a

higher minimum rent upon turnover as a way of rolling percentage rent into a more secure income stream.

The clauses which cover the payment of percentage rent must be carefully read to see how the rent is to be

paid, i.e., annually, or monthly. In some cases where the lease provides for a long term made up of two, ten

year terms, the lease may provide for an increase in the minimum rent based upon a combination of

minimum rent and percentage rent. A sample clause is as follows:

“Option to Renew”: The Tenant has the option to renew this lease for a further ten (10) years. There

shall be no right to further renewal after the first renewal. The terms and conditions

of this renewal remain the same as the terms and conditions of the Lease in effect,

save and except for the minimum rent. The annual minimum rent will be adjusted

at the commencement of year one (l) of the renewal term as well as at the

commencement of year six (6) of the renewal term to the average rent (minimum

plus percentage rent) paid over the previous two (2) years of the term.

The minimum rent according to this clause can result in a rate that is considerably in excess of market. A

more dangerous situation for the lessee can be created if the gross sales during the last two years of the

initial term or the first renewal period are high but then fall dramatically. The minimum rent could be

excessive and depending upon the strength of the tenant, might force the lessee out of business. For

example:

3

Alexander, A. & Muhlebach, R, Managing and Leasing Commercial Properties, Institute of Real Estate Management, 2007, p.68.

Valuation of Leasehold Interests

6.29

Example:

The lease calls for a minimum rent based on $200 psf for 100 sq. ft. or $20,000 per annum for the

first ten years. There is also a provision for a percentage rent on sales over $400,000 at the rate of

5%. Let us assume that the gross sales during the last three years of the original ten year term reach

$1,000,000 per annum. The total rent payable to the landlord would be:

(a) Minimum rental $ 20,000

(b) Percentage rental: $1,000,000

less ceiling $ 400,000

$ 600,000

Percent rent $ 600,000

× 5%

$ 30,000

Minimum base rent: $ 20,000

Percent rent: $ 30,000

Total rent: $ 50,000

Based upon the wording of the renewal clause, the minimum rental for the first year of the ten year renewal

term and throughout the full ten years will be at least $50,000. This equates to a rate of $500 psf and could