PUBLIC

-1-

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA

BEFORE THE FEDERAL TRADE COMMISSION

COMMISSIONERS: Lina M. Khan, Chair

Rebecca Kelly Slaughter

Alvaro M. Bedoya

In the Matter of

The Kroger Company

and

Albertsons Companies, Inc.

Docket No. D-9428

REDACTED PUBLIC

VERSION

COMPLAINT

Pursuant to the provisions of the Federal Trade Commission Act (“FTC Act”), and by

virtue of the authority vested in it by the FTC Act, the Federal Trade Commission

(“Commission”), having reason to believe that Respondents The Kroger Company and

Albertsons Companies, Inc., have executed a definitive agreement in violation of Section 5 of the

FTC Act, 15 U.S.C. § 45, which if consummated would violate Section 7 of the Clayton Act, as

amended, 15 U.S.C. § 18, and Section 5 of the FTC Act, and it appearing to the Commission that

a proceeding by it in respect thereof would be in the public interest, hereby issues its complaint

pursuant to Section 5(b) of the FTC Act, 15 U.S.C. § 45(b), and Section 11(b) of the Clayton

Act, 15 U.S.C. § 21(b), stating its charges as follows:

I. NATURE OF THE CASE

1. In the fall of 2022, Kroger and Albertsons executed an agreement for Kroger to buy

100% of the equity of Albertsons for approximately $24.6 billion. The proposed acquisition is by

far the largest supermarket merger in U.S. history. If allowed, this merger would substantially

lessen competition, likely resulting in Americans paying millions of dollars more for food and

other essential household goods, as well as reducing the ability of hundreds of thousands of

workers to secure better wages and benefits.

2. The stakes for Americans are exceptionally high. Over the past four years, grocery prices

have risen significantly. The increase in prices has meant that more and more Americans are

reportedly struggling with the cost of putting food on the table and feeding their families. Our most

vulnerable citizens have suffered the most: a 2022 report showed that over a third of households

with income below the federal poverty line are food insecure, with many low-income families

spending almost one-third of their income on food.

3. Especially against this backdrop, the merger of two grocery giants could have severe

consequences for consumers in communities across the country. Kroger and Albertsons are the #1

PUBLIC

-2-

and #2 traditional supermarket chains in the United States. Their combined footprint is vast—

approximately 5,000 stores, 4,000 retail pharmacies, and 700,000 employees across 48 states.

4. Kroger and Albertsons acquired their massive size through numerous mergers over the

past three decades, part of a broader trend of significant consolidation in the United States grocery

industry. Examples of Kroger-owned supermarket banners include Fred Meyer, Quality Food

Center (QFC), King Soopers, Mariano’s, Ralphs, Smith’s, and Harris Teeter, while Albertsons-

owned banners include Safeway, Vons, Jewel-Osco, Haggen, and Carrs, among others.

5. Today, Kroger and Albertsons compete intensely for consumers and workers in

hundreds of communities across the country. As Albertsons’s CEO declared,

Kroger executives, in turn,

describe Albertsons banners as “our #1 direct competitor” and For

millions of consumers, direct competition between Kroger and Albertsons has brought grocery

prices down and the quality of grocery products and services up.

6. The proposed acquisition would destroy this competition, leaving consumers to foot the

bill. As an Albertsons executive communicated to colleagues shortly after the merger

announcement,

Similarly, Albertsons’s Chief

Operating Officer emailed Albertsons’s Division Leadership on the day the deal was announced,

A Kroger executive commented on some of the geographies impacted by the deal,

The

destruction of competition between these two head-to-head rivals risks raising prices, worsening

services, and lowering quality for the millions of consumers who rely on Kroger and Albertsons

for their groceries and other everyday goods.

7. Consumers are not the only ones who will pay the price if the proposed acquisition is

completed: the hundreds of thousands of people who work for Kroger and Albertsons would suffer

too. Today, Kroger and Albertsons compete aggressively with one another to hire and retain

grocery workers, principally through collective bargaining negotiations with local unions (i.e., the

process by which workers, though the unions that represent them, negotiate agreements with their

employers that determine the terms and conditions of employment). This competition has resulted

in higher wages, better benefits, and improved working conditions for employees. The proposed

acquisition would eliminate this competition, threatening the ability of hundreds of thousands of

grocery store workers to secure stronger contracts with improved wages and benefits.

8. Kroger’s and Albertsons’s own executives recognized that the proposed acquisition

would be an unlawful merger under the antitrust laws. For example, when rumors of a merger

emerged, one Albertsons executive stated,

Another Albertsons

executive agreed:

Another Kroger executive stated the day before the deal was announced,

PUBLIC

-3-

9. These executives were right to be concerned. In many hundreds of local supermarket

and labor markets, the proposed acquisition would increase Kroger’s market shares by so much as

to be presumptively unlawful under the antitrust laws.

10. Recognizing that their proposed merger would be unlawful, Kroger and Albertsons

propose to divest a hodgepodge of several hundred of their more than 5,000 stores and castoff

assets to C&S Wholesale Grocers (“proposed divestiture”). Until very recently, C&S’s century-

long business model was that of a wholesale supplier specializing in grocery supply chain

solutions. As recently as 2021, C&S operated only two retail supermarkets. Today, C&S operates

twenty-three supermarkets and a single retail pharmacy, mostly in New York and Wisconsin.

Through this divestiture, C&S is seeking to grow its retail footprint nearly 18-fold overnight. Yet,

up until 2021, C&S stated in its quarterly reports that “[w]e do not intend to grow our grocery

retailing operations or to operate the retail grocery stores in the long term.”

11. Divesting these individual assets to a grocery wholesaler with limited experience

operating retail supermarkets will fail to mitigate the substantial harm to consumers and workers

from lost competition between Kroger and Albertsons. C&S would be acquiring a patchwork of

assets cobbled together by Kroger’s antitrust lawyers, not a standalone business likely to succeed.

The proposed divestiture ignores hundreds of affected markets that serve millions of consumers,

as well as the merger’s destruction of labor market competition. C&S will face multiple significant

obstacles stitching together a viable business—let alone a successful competitor—from the

assortment of divested stores, and any operational shortcoming would imperil competition in many

local markets. There are major execution risks associated with Respondents’ proposed divestiture,

and the American public —not Respondents—would bear the costs of any failure.

II. JURISDICTION

12. Respondents, and each of their relevant operating entities and parent entities are, and

at all relevant times have been, engaged in commerce or in activities affecting “commerce” as

defined in Section 4 of the FTC Act, 15 U.S.C. § 44, and Section 1 of the Clayton Act, 15 U.S.C.

§ 12.

13. The proposed acquisition constitutes a transaction subject to Section 7 of the Clayton

Act, 15 U.S.C § 18.

III. RESPONDENTS

14. Respondent Kroger is the largest traditional supermarket chain and the largest

employer of union grocery workers in the United States. In 2022, Kroger generated over $148

billion in revenues. Today, Kroger operates approximately 2,726 supermarkets and 2,252 retail

pharmacies under numerous banners (e.g., Kroger, Fred Meyer, Quality Food Center (QFC),

Baker’s, City Market, Dillons, Food 4 Less, Foods Co, Fry’s, Gerbes, Harris Teeter, JayC, King

Soopers, Mariano’s, Metro Market, Pay-Less, Pick’n Save, Ralphs, Ruler, Smith’s) across thirty-

six states as shown in the illustration below.

PUBLIC

-4-

Kroger also employs approximately 430,000 workers and is a party to over 300 collective

bargaining agreements, with labor unions representing most of its workforce.

15. Kroger’s present-day portfolio of stores and banners is the product of four decades of

continuous consolidation:

• 1983: Kroger acquired Dillon Companies (including Dillons, King Soopers, City

Market, Fry’s, and Gerbes banners)

• 1999: Kroger acquired JayC (including JayC and Ruler banners)

• 1999: Kroger acquired Pay Less

• 1999: Kroger acquired Fred Meyer for ~$13 billion (including Fred Meyer, Ralphs,

Food 4 Less, QFC, and Smith’s banners)

• 2001: Kroger acquired Baker’s

• 2014: Kroger acquired Harris Teeter for ~$2.5 billion

• 2015: Kroger acquired Roundy’s for ~$800 million (including Roundy’s, Pick ‘N

Save, Metro Markets, and Mariano’s banners)

PUBLIC

-5-

Touting its history of growth by acquisitions, Kroger notes on its website that, “Mergers have

played a key role in our growth.”

16. Respondent Albertsons is the second largest traditional supermarket chain and the

second largest employer of union grocery workers in the United States. In 2022, Albertsons

generated approximately $72 billion in revenues. Albertsons operates approximately 2,276

supermarkets and 1,722 retail pharmacies under numerous banners (e.g., Albertsons, Safeway,

Haggen, Acme, Andronico’s, Amigos, Balducci’s, Carrs, Eagle Quality Center, Jewel-Osco, Kings

Food Markets, Lucky, Market Street, Pak‘N Save, Pavilions, Randalls, Shaw’s, Star Market, Tom

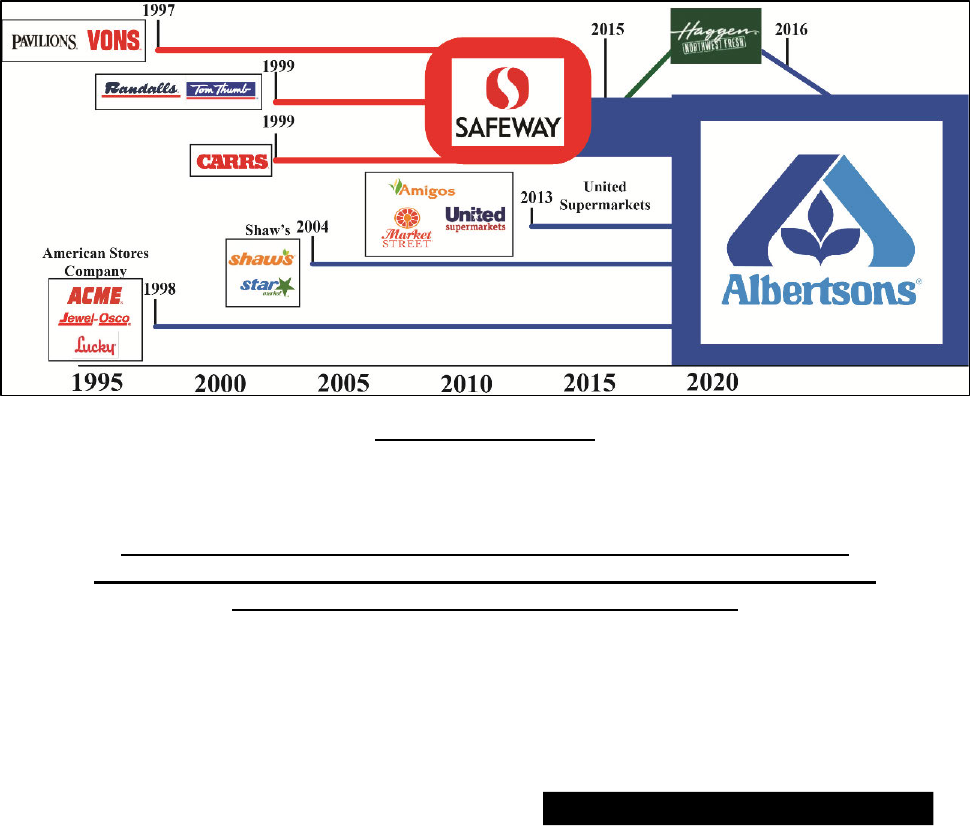

Thumb, United Supermarkets, Vons) across thirty-five states as shown in the illustration below.

Albertsons also employs over 290,000 workers, most of whom are covered by collective

bargaining agreements.

PUBLIC

-6-

17. Much like Kroger, Albertsons Companies today is the product of serial acquisitions:

• 1998: Albertsons acquired American Stores Company for ~$13 billion (including

Jewel-Osco, Lucky, and Acme banners)

• 2004: Albertsons acquired Shaw’s Supermarkets for ~$2.5 billion (including

Shaw’s and Star Market banners)

• 2013: Albertsons acquired United Supermarkets for ~$385 million (including

United, Market Street, and Amigos banners)

• 2015: Albertsons acquired Safeway for ~$9.2 billion (including Safeway, Carrs,

Tom Thumb, Randalls, Vons, and Pavilions banners)

• 2016: Albertsons acquired Haggen, including numerous stores it had previously

divested to Haggen in the Safeway transaction just a year prior.

IV. THE ACQUISITION

18. On October 13, 2022, Kroger and Albertsons entered into an Agreement and Plan of

Merger setting forth the terms of the proposed acquisition.

V. THE PROPOSED ACQUISITION MAY SUBSTANTIALLY LESSEN

COMPETITION IN LOCAL MARKETS FOR THE SALE OF FOOD AND

GROCERY PRODUCTS AT SUPERMARKETS

19. Kroger and Albertsons are two of the largest supermarket chains in thousands of local

communities throughout the country. In hundreds of those communities, the proposed acquisition

would create a single supermarket with market shares so high as to be presumptively unlawful

under the antitrust laws. The proposed acquisition would also eliminate the substantial head-to-

head competition between Kroger and Albertsons that exists today, which risks higher prices and

lower quality for consumers. Albertsons’s executives have acknowledged that the combination of

these two companies would harm competition, writing:

PUBLIC

-7-

20. Respondents are unique in their scale and size. Today, Kroger’s and Albertsons’s

supermarkets are part of an ecosystem of store banners (e.g., Safeway, Fred Meyer, and QFC) that

benefit from manufacturing and distribution networks that operate across broad areas of the

country and enjoy local brand recognition. Kroger’s go-to-market strategy is to benefit from

Albertsons also benefits from the company’s

21. Respondents organize their supermarkets into “divisions,” which are geographic

organizational units that have some level of operational autonomy. Respondents’ supermarkets

also benefit from broad banner and operational division-level branding, marketing, pricing, and

promotional strategies. Respondents’ strategies include building a profitable “flywheel” (assets

that work together to enable continuous growth) of data science capabilities, including loyalty

program data that provide insights into consumer behavior and are utilized in retail media

networks. These corporate capabilities are integral to the success of Respondents’ individual

stores. According to Albertsons’s CEO:

22. Kroger and Albertsons also offer additional services to attract supermarket customers,

such as fuel stations and pharmacies. For instance, Respondents recognize that offering pharmacy

services in their supermarkets can help drive customer traffic, and that customers who come to the

pharmacies tend to also purchase groceries. Offering these additional services contributes to the

success of Respondents’ overall supermarket business.

23. By leveraging these networks and services, Kroger and Albertsons compete head-to-

head across multiple dimensions. For example, Albertsons’s Portland Division has developed a

specific plan for success against Kroger to and Kroger’s

QFC division refers to Safeway as its “#1 direct competitor.” Respondents’ supermarkets alter

their pricing and promotions in response to each other and compete with one another to improve

the quality of their products and services. Eliminating this head-to-head competition between

Respondents may lead to higher prices and reduced services for consumers.

A. SUPERMARKETS ARE A RELEVANT PRODUCT MARKET

24. The retail sale of food and other grocery products in traditional supermarkets and

supercenters constitutes a relevant product market. For brevity, this relevant product market is

referred to here as “supermarkets.”

25. Supermarkets offer consumers convenient “one-stop shopping” for food and grocery

products, which, in Kroger’s words, is a “simpler and more convenient” alternative to multiple

shopping trips. Indeed, Kroger boasts that “one-stop shopping” is their “innovation #1” and has

grown into something that would make [company founder] Barney [Kroger] smile.” Compared to

other types of food retailers, supermarkets typically have a broad and deep product assortment of

tens of thousands of stock-keeping units (“SKUs”) in a variety of package sizes, as well as a deep

inventory of those items. To accommodate the large number of food and non-food products

PUBLIC

-8-

necessary for one-stop shopping, supermarkets are large stores that typically have at least 10,000

square feet of selling space.

26. Supermarkets allow customers to purchase most or all of their food and grocery

shopping requirements in a single trip to a store that offers substantial products in each of the

following categories: bread and baked goods; dairy products; refrigerated food and beverage

products; frozen food and beverage products; fresh and prepared meats and poultry; fresh fruits

and vegetables; shelf-stable food and beverage products, including canned, jarred, bottled, boxed,

and other types of packaged products; staple foodstuffs, such as salt, sugar, flour, sauces, spices,

coffee, tea, and other staples; other grocery products, including nonfood items such as soaps,

detergents, paper goods, other household products, and health and beauty aids; and, to the extent

permitted by law, wine, beer, or distilled spirits. Supermarkets also offer customer service options

including deli, butcher, seafood, bakery, prepared meals (e.g., sushi, hot bar), or floral counters.

27. Supermarkets recognize other supermarkets as a distinct type of food and grocery

retailer. For example, supermarkets track and respond to other supermarkets’ promotions and

customer-service options. When determining their pricing, supermarkets primarily consider the

pricing of other supermarkets. This is true for Respondents. Kroger predominantly price checks

Similarly, Albertsons’s

pricing program focuses on

28. A relevant antitrust market need not include all substitute products or services. The loss

of competition between a narrower group of substitutes can cause harm, making the narrower

group a properly defined antitrust market. The hypothetical monopolist test is a tool used to

determine if a group of products (i.e., type of retailers) is sufficiently broad to be a properly defined

antitrust product market. If a single firm (i.e., a hypothetical monopolist) seeking to maximize

profits controlled all sellers of a set of products or services and likely would undertake a small but

significant and non-transitory increase in price or other worsening of terms (“SSNIPT”), then that

group of products (i.e., type of retailer) is a properly defined antitrust product market.

29. A hypothetical monopolist of supermarkets likely would undertake a SSNIPT on

consumers. In response to a SSNIPT, supermarket customers would not shift enough of their

purchases to non-supermarket retail formats to make a hypothetical monopolist of supermarkets

unlikely to undertake a SSNIPT. The reason consumers would not shift a significant enough

volume of purchases is because these non-supermarket retail offerings provide a very

differentiated customer experience. For example:

• Club stores (e.g., Costco, Sam’s Club) require membership fees, typically offer

larger package sizes, and frequently rotate their product assortments. Club stores

have more square footage but offer far fewer food and grocery SKUs than

supermarkets. Club stores also have fewer store locations than supermarkets,

requiring consumers to travel longer distances.

• Limited assortment stores (e.g., Aldi, Lidl) offer a differentiated, narrower selection

of product SKUs. Most of the SKUs limited assortment stores offer are private label

(i.e., store brand) as opposed to national brands. Limited assortment stores often

offer products on a rotating, limited time, or seasonal basis, meaning customers are

PUBLIC

-9-

not always able to find the products they want. Limited assortment stores generally

have smaller square footage and do not offer as many customer service options,

including deli, butcher, bakery, prepared food, and pharmacy, as supermarkets

offer.

• Premium natural and organic stores (“PNOS”) (e.g., Whole Foods, Sprouts Farmers

Market) focus on a set of customers that is distinct from supermarket customers,

and PNOS generally have higher prices than supermarkets. PNOS also carry a

differentiated, narrower product assortment that is more focused on organic and

fresh products.

• Dollar stores offer a much narrower range of grocery product SKUs than

supermarkets (i.e., little or no fresh produce, meat, or dairy). Dollar stores also do

not offer the kind of customer service options, including deli, butcher, seafood,

bakery, prepared meals, or floral counter, that supermarkets offer.

• E-commerce retailers (e.g., Amazon.com) offer a very different consumer

experience from in-person shopping across many dimensions. For example, e-

commerce retailers do not allow customers to inspect produce before purchase,

require waiting for delivery, and/or require scheduling convenient delivery

windows for perishable products. E-commerce retailers also may charge additional

service and delivery fees that increase the total cost of grocery orders.

30. The price increase would be profitable for the hypothetical monopolist because

supermarkets would not lose sufficient sales to non-supermarkets to make the price increase

unprofitable. The fact that a hypothetical monopolist of supermarkets would likely undertake a

SSNIPT means that other kinds of retailers are not a sufficient competitive constraint on

supermarkets to prevent a SSNIPT. Therefore, supermarkets constitute a properly defined product

market.

31. Grocery delivery services (e.g., Instacart, DoorDash) are not in the relevant product

market. Grocery delivery services are not independent suppliers of grocery products; rather,

grocery delivery service shoppers procure products from brick-and-mortar retailers and deliver

them to customers, typically during a pre-scheduled time window. Grocery delivery services are

partners to, not substitutes for, brick-and-mortar retailers.

B. LOCAL AREAS AROUND STORES ARE RELEVANT GEOGRAPHIC

MARKETS

32. Customers prefer to purchase grocery products at retailers near where they live or work.

Supermarket competition therefore primarily occurs locally. Relevant geographic markets for

retail supermarkets are localized areas around each store. Indeed, in their internal documents and

securities filings, Respondents focus their competitive analysis on a radius of several miles around

each store, but that may vary somewhat due to local conditions.

33. Localized markets around Respondents’ stores within the below areas are geographic

markets in which to assess the competitive effects of the proposed acquisition. A hypothetical

monopolist controlling all supermarkets in any one of these localized markets within one of the

below core-based-statistical areas (i.e., metropolitan and micropolitan areas) or rural geographies

could profitably implement a SSNIPT in that market.

PUBLIC

-10-

• Alaska: Anchorage; Fairbanks; Juneau; Kenai; Soldotna

• Arizona: Flagstaff; Lake Havasu City-Kingman; Payson, Phoenix-Mesa-Chandler;

Prescott Valley-Prescott; Sierra Vista-Douglas; Tucson; Yuma

• California: Bakersfield; El Centro; Fresno; Los Angeles-Long Beach-Anaheim; Oxnard-

Thousand Oaks-Ventura; Riverside-San Bernardino-Ontario; Salinas; San Diego-Chula

Vista-Carlsbad; San Francisco-Oakland-Berkeley; San Luis Obispo-Paso Robles; Santa

Maria-Santa Barbara

• Colorado: Alamosa; Boulder; Cañon City; Colorado Springs; Cortez; Delta; Denver-

Aurora-Lakewood; Durango; Edwards; Fort Collins; Fraser; Granby; Grand Junction;

Greeley; Gunnison; Montrose; Pueblo; Steamboat Springs

• District of Columbia and Virginia: Washington-Arlington-Alexandria

• Idaho: Boise-Meridian-Nampa; Coeur d’Alene; Idaho Falls; Pocatello; Twin Falls

• Illinois and Indiana: Bloomington; Chicago-Naperville-Elgin; Kankakee

• Louisiana: Alexandria; Lake Charles; Shreveport-Bossier City

• Maryland: Baltimore-Columbia-Towson; Easton

• Montana: Bozeman; Great Falls; Kalispell

• New Mexico: Albuquerque; Farmington; Santa Fe; Taos

• Nevada: Elko; Las Vegas-Henderson-Paradise; Pahrump; Reno

• Oregon: Albany-Lebanon; Bend; Coos Bay; Corvallis; Eugene-Springfield; Grants Pass;

Klamath Falls; Medford; Newport; Portland-Vancouver-Hillsboro; Roseburg; Salem; The

Dalles; Tillamook

• Texas: Dallas-Fort Worth-Arlington; Houston-The Woodlands-Sugar Land; Sherman-

Denison

• Utah: Salt Lake City; St. George

• Washington: Bellingham; Bremerton-Silverdale-Port Orchard; Ellensburg; Hadlock;

Kennewick-Richland; Longview; Mount Vernon-Anacortes; Olympia-Lacey-Tumwater;

Port Angeles; Port Townsend; Seattle-Tacoma-Bellevue; Shelton; Spokane-Spokane

Valley; Wenatchee; Yakima

• Wyoming: Casper; Cheyenne; Gillette; Jackson; Rock Springs

C. THE PROPOSED ACQUISITION IS PRESUMPTIVELY UNLAWFUL

34. The Herfindahl-Hirschman Index (“HHI”) is a well-established method for calculating

concentration in a market. The HHI is the sum of the squares of the market shares of the market

participants. For example, a market with five firms, each with 20% market share, would have an

HHI of 2000 (20

2

+ 20

2

+ 20

2

+ 20

2

+20

2

= 2000). The HHI is low when there are many small

PUBLIC

-11-

firms and grows higher as the market becomes more concentrated. A market with a single firm

would have an HHI of 10,000 (100

2

= 10,000).

35. The Department of Justice and the Federal Trade Commission jointly publish the

Merger Guidelines. Rooted in established caselaw and widely accepted economic thinking, the

Merger Guidelines outline the legal tests, analytical frameworks, and economic methodologies

both agencies use to assess whether transactions violate the antitrust laws, including measuring

market shares and changes in market concentration from a merger. The Merger Guidelines—

themselves guided by numerous court decisions—support using the HHI method to calculate

market concentration.

36. The increase in market concentration caused by the proposed acquisition is indicative

of the merger’s likely negative impact on competition. The Merger Guidelines explain that a

merger that significantly increases market concentration is presumptively unlawful. Specifically:

•

A merger that creates a firm with a market share of over 30 percent and that

increases the HHI of the market by more than 100 points is presumed to

substantially lessen competition in that market and is thus presumptively illegal.

•

A merger is also likely to create or enhance market power—and, again, is

presumptively illegal—when the post-merger HHI exceeds 1800 and the merger

increases the HHI by more than 100 points.

37. The proposed acquisition is presumptively illegal in overlapping local markets

surrounding more than 1500 Kroger and Albertsons supermarkets within the above referenced

geographic areas. The proposed acquisition is presumed likely to create or enhance market

power—and is presumptively illegal—in each of these local geographic markets because the

merger increases the HHI by more than 100 points and (i) Respondents’ combined market shares

exceed 30 percent or (ii) the post-merger HHI exceeds 1800.

38. Even if the non-supermarket retail formats described above are included in the relevant

product market, the proposed acquisition is still presumptively unlawful in most of the identified

geographic markets.

D. THE PROPOSED ACQUISITION WOULD ELIMINATE HEAD-TO-HEAD

COMPETITION BETWEEN RESPONDENTS

39. The elimination of head-to-head competition between Respondents also makes the

proposed acquisition unlawful. A merger is unlawful if it substantially lessens competition

between the parties independent of the analysis of market shares, as recognized by the Merger

Guidelines.

40. The proposed acquisition would eliminate substantial head-to-head competition

between Respondents in the communities in which both firms operate supermarkets today. The

likely result would be higher prices, lower quality, and worse service for consumers around the

country.

41. Pricing competition. Kroger’s and Albertsons’s loyalty data indicates that their

overlapping supermarkets compete for the same customer base, drawing shoppers from the same

local communities. Today, Kroger and Albertsons engage in aggressive price competition that

PUBLIC

-12-

benefits these consumers. For example, both Respondents frequently price check each other at a

local level and often alter pricing in response to competition from each other.

This pricing competition between

Respondents exists in both base pricing (non-promotional price) and promotional pricing (sale

price). The proposed acquisition would eliminate that competition, leading to higher prices for

consumers.

42. In some divisions, Kroger benchmarks its base pricing

Additionally, for multiple product categories, Kroger policies demand that its base

prices

43. Likewise, Albertsons identifies Kroger

Albertsons checks prices

Using the price check data, Albertsons’s pricing software

alerts employees when an item’s base price is too high or low

Albertsons’s long-term goal is to create an

This price competition has benefited consumers in

the form of lower prices.

44. Kroger and Albertsons also compete by offering promotional pricing discounts on

products. Both Respondents engineer their promotional programs and discounts in part to drive

customers towards their own supermarkets, and away from the other’s supermarkets. Respondents

also monitor each other’s promotional offers and respond accordingly. In divisions where

Respondents’ supermarkets overlap, Kroger routinely compares

Albertsons also for example, Albertsons’s Denver

Division President testified that Albertsons strives

45. Promotional competition between Kroger and Albertsons is a regular occurrence. For

example, in response to Fred Meyer (Kroger) ads in Portland, Oregon, Albertsons’s Chief

Operating Officer wrote,

Albertsons’s Vice President of Marketing and Merchandising commented,

In 2022, Albertsons’s Senior Vice President of Marketing and

Merchandising for the Seattle Division noted in response to Fred Meyer ads,

Again, the proposed acquisition would eliminate promotional pricing

competition between Kroger and Albertsons, leading to higher prices for consumers.

46. Product quality competition. Kroger and Albertsons also compete with one another

to improve the quality and variety of their products and offerings, such as the freshness and

assortment of their produce. Kroger’s internal analyses show that

PUBLIC

-13-

and

Similarly, Albertsons’s Division President in Portland stated in 2022,

and

that Albertsons needed to to compete with Kroger

and Walmart.

47. Recognizing the importance of freshness and the assortment of fresh products to

customer choice, Respondents compete closely to offer the freshest, highest quality produce.

Consumers regularly benefit from this competition. For example, after noting the selection of in-

store cut produce at Vons (Albertsons) stores in late 2022, a Ralphs (Kroger) produce manager

directed his team Similarly, in April

2022, Albertsons conducted a test comparing the freshness of

48. Kroger and Albertsons also compete by monitoring each other’s branded and private-

label products. For example, in 2020, Kroger compared the quality

As a result of this assessment, Kroger recognized a need

The proposed acquisition would eliminate that

competition, leading to lower quality private-label offerings for consumers.

49. Store condition and customer service competition. Respondents try to attract

customer volume by prioritizing store re-models where they face more robust competition. For

example, when Kroger opened a Fry’s supermarket in Arizona near an Albertsons, the Albertsons’s

District Manager noted its store was

He added,

Also, for example, a Ralphs employee stated a particular store was a

50. Competition between Respondents also spurs them to offer superior customer services.

Albertsons’s 2022 Portland Division plan to compete against Kroger included

The

improved customer services include store hours and pick-up centers. For example, in 2022, the

president of Kroger’s QFC division to bring

them closer to its “#1 direct competitor,” Albertsons’s Safeway. Competition between the

Respondents has also motivated them to improve offerings such as curb-side pickup. In 2021,

Kroger’s Chief Merchant and Marketing Officer commented to its CFO:

The following

year, the same Kroger executive expressed urgency about improving Kroger’s pick-up services

after

Albertsons also decided to add pick-up centers at some of its supermarkets

directly in response to actions by Kroger,

51. Respondents also compete for supermarket customers through robust in-store services

such as meat-cutting, bakeries, Starbucks counters, floral counters, pharmacies, and more. For

example, Albertsons saw an opportunity to take advantage and win customers after seeing

PUBLIC

-14-

unstaffed deli counters at Kroger’s Fred Meyer. Albertsons’s Chief Operating Officer suggested

that which the Seattle Division President said

was Albertsons planned to

Also, for example, in 2022, Kroger’s Ralphs Division President

52. Pharmacy services competition. Offering pharmacy services is an important way that

Respondents’ supermarkets compete to attract supermarket customers because attracting

pharmacy patients increases supermarket revenue from customers who are also purchasing

groceries. For example, when Kroger went out-of-network with a major pharmacy benefits

manager (meaning beneficiaries of certain health insurance plans could no longer fill prescriptions

at Kroger pharmacies), Albertsons viewed the event as

Respondents recognize that

pharmacy patients visit stores more frequently and spend more during shopping trips than shoppers

who do not visit the pharmacies. As Albertsons’s Director of Managed Care stated,

Kroger cited competition with

53. Respondents compete with each other to win pharmacy patients, retain prescriptions,

and to offer other pharmacy services (e.g., vaccines). For example, in 2021 Kroger offered a fuel

points incentive for all COVID-19 vaccine doses in

Also in 2021, Kroger began offering grocery promotions in

Dallas for COVID-19 patients After Kroger went out

of certain payor networks in 2023,

Albertsons

began offering pharmacy patients a $75 discount for grocery items when they transferred a

prescription.

54. The competition to fill prescriptions and provide other pharmacy services incentivizes

Respondents to offer promotions and adjust pharmacy hours and staffing to be more attractive to

pharmacy patients. For example, Kroger’s King Soopers banner

55. The proposed acquisition, by reducing competition between Kroger and Albertsons for

supermarket grocery customers, would reduce the Respondents’ incentive to continue offering the

same level of pharmacy services to attract those customers. The combined Kroger/Albertsons

would have a reduced incentive to offer promotions or improved customer service.

56. The proposed acquisition would eliminate this head-to-head competition between

Respondents’ supermarkets, reducing their incentives to improve pricing, product quality, and

customer services.

PUBLIC

-15-

VI. THE PROPOSED ACQUISITION MAY SUBSTANTIALLY LESSEN

COMPETITION FOR LABOR

57. A merger of competing buyers, including employers as buyers of labor, can

substantially lessen competition between the merging buyers. The same tools used to assess the

effects of a merger of sellers can be used to analyze a merger of employers as buyers of labor.

58. The proposed acquisition may substantially lessen competition between Kroger and

Albertsons for employees. Respondents are each massive employers of grocery workers, with over

700,000 combined employees throughout the country, and they compete aggressively to hire and

retain workers in the areas where their supermarket operations overlap.

59. Respondents monitor wages and benefits set at local competitors, including each other,

and often attempt to match or exceed competing wage and benefit offers. To retain high-

performing workers, Respondents often promote them, offer retention bonuses, or improve their

hours. Kroger and Albertsons also try to poach grocery workers from each other.

60. There are many real-world examples of this competition. For example, in 2021,

Albertsons’s Executive Vice President of Retail Operations directed district managers, sales

managers, and store directors to

He emphasized, by hiring Kroger’s workers,

Also in 2021, Kroger’s Fred Meyer Division President emailed

Kroger’s Senior Vice President of Retail Operations about

61. This competition for workers is most acute and apparent in the context of collective

bargaining negotiations with union grocery workers. Most of Respondents’ workers are members

of unions, predominantly the United Food and Commercial Workers (“UFCW”). Kroger employs

UFCW union grocery workers in 30 states, while Albertsons has union grocery workers in 26

states. Indeed, in Alaska, Arizona, California, Colorado, Idaho, Illinois, Indiana, Montana, New

Mexico, Nevada, Oregon, Utah, Virginia, Washington, and Wyoming, both Kroger and Albertsons

operate stores that employ UFCW union grocery workers.

62. Today, in many markets where both Respondents employ union workers, the unions

that represent grocery workers leverage the fact that Kroger and Albertsons are separate companies

competing for customers and workers to negotiate better terms of employment for union grocery

workers. The proposed acquisition would eliminate that competition, likely leading to lower wages

and reduced benefits, opportunities, and quality of workplace conditions and protections for

thousands of Respondents’ employees.

A. UNION GROCERY LABOR IS A RELEVANT MARKET

63. Union grocery labor is a relevant market in which to analyze the probable effects of the

proposed acquisition. Unions typically negotiate collective bargaining agreements (“CBAs”) with

grocery employers, including Respondents, on behalf of their worker members every few years.

CBAs determine each union worker’s wages, health and pension benefits, scheduling, leave, and

myriad other workplace conditions. Union grocery workers can move between grocery employers

covered by their union while retaining their pension and healthcare benefits, as well as other

valuable workplace benefits and protections provided by the CBAs. If a union grocery worker

PUBLIC

-16-

leaves for a non-union employer, however, the worker will lose any non-vested CBA benefits and

protections.

64. Union grocery workers value their robust pension and healthcare benefits, as well as

other benefits and protections provided by the CBAs. Because union grocery worker pensions vest

after a certain number of years of employment, and union healthcare benefits often improve over

time, union grocery workers have a strong preference to remain with their union employers.

B. LOCAL CBA AREAS ARE RELEVANT GEOGRAPHIC MARKETS

65. Respondents typically negotiate CBAs that cover defined localized areas where they

operate union supermarkets. When preparing for collective bargaining negotiations, Respondents

survey wages and benefits in the local areas subject to the CBA. Recognizing that grocery workers

prefer to work near where they live, Respondents also make job posting and hiring decisions

locally, typically at the store level.

66. The geographic areas covered by each CBA’s jurisdiction, referred to here as the local

CBA areas, are relevant geographic markets in which to analyze the proposed acquisition’s

probable effects.

67. Because the unions gain leverage by playing competing grocery chains against each

other during CBA negotiations, a hypothetical operator of all union grocery stores within a local

CBA area would likely undertake the equivalent of a SSNIPT (i.e., a small but significant non-

transitory worsening of employment terms) with respect to its CBAs.

C. THE PROPOSED ACQUISITION IS PRESUMPTIVELY UNLAWFUL

68. Kroger and Albertsons are the two largest employers of union grocery labor in the

United States. In many states, including Arizona, California, Colorado, Illinois, New Mexico,

Nevada, Oregon, and Washington, Respondents both negotiate with the same local unions, and

Kroger and Albertsons are often the only two, or two of few, union grocery employers. The

proposed acquisition is presumed likely to lessen competition—and is thus presumptively illegal—

in many local CBA areas within each state where Respondents negotiate with the same local unions

because the combined firm will enjoy a market share of over 30 percent and the merger increases

the HHI of the market by more than 100 points. For example, the Respondents have a combined

share of union grocery labor exceeding 65% in each of the below local CBA areas. Indeed, the

proposed acquisition would be a merger to monopsony in approximately half of the local CBA

areas listed below and would leave the merged Kroger/Albertsons as the only remaining employer

of union grocery labor in those CBA areas. A non-exhaustive list of shared CBA areas is below:

• California: (i) Imperial, Inyo, Kern, Los Angeles, Mono, Orange, Riverside, San

Bernadino, San Diego, San Luis Obispo, Santa Barbara, and Ventura Counties;

• Colorado: (i) Boulder and Louisville; (ii) Broomfield; (iii) Colorado Springs; (iv)

Denver; (v) Fort Collins; (vi) Grand Junction and Clifton; (vii) Greeley; (viii) Longmont;

(ix) Loveland; (x) Parker; (xi) Pueblo;

• Oregon: (i) Bend, Redmond, and Madras; (ii) Coos and Western Douglas Counties; (iii)

Eugene (Lane County); (iv) Florence; (v) Jackson and Josephine Counties; (vi) Lincoln

County; (vii) Portland (Multnomah, Washington, Clackamas, Columbia, and Yamhill

PUBLIC

-17-

Counties); (viii) Roseburg, Sutherlin, Winston, Riddle, and Myrtle Creek; (ix) Salem

(Marion, Polk, Linn, and Benton Counties); (x) Wasco and Hood River Counties;

• Washington: (i) Chelan, Douglas, and Kittitas Counties; (ii) Clark County; (iii) Cowlitz

and Wahkiakum Counties; (iv) Jefferson and Clallam Counties; (v) King, Kitsap, and

Snohomish Counties; (vi) Island, Skagit, and Whatcom Counties; (vii) Mason and

Thurston Counties; (viii) Spokane County; (ix) Yakima County.

D. THE PROPOSED ACQUISITION WOULD ELIMINATE COMPETITION

BETWEEN RESPONDENTS FOR UNION GROCERY LABOR

69. Separate from the increase in concentration, the elimination of current head-to-head

competition between Respondents for union grocery labor in many of their shared local CBA areas

also makes the proposed acquisition unlawful.

70. By eliminating the current competition for union grocery labor between Kroger and

Albertsons, the proposed acquisition would prevent the unions from being able to play them off

each other during collective bargaining negotiations, substantially increasing Kroger’s negotiating

leverage. Kroger could use this increased negotiating leverage to reduce (or refuse to increase)

wages, to reduce (or refuse to improve) worker benefits, and to degrade (or refuse to improve)

working conditions or commit to fewer workplace protections.

71. Kroger and Albertsons are the two largest union grocery operators in the United States.

Kroger and Albertsons each negotiate with local unions representing their workforces to determine

wages, benefits, and working conditions for union grocery workers. Where Respondents overlap,

they compete to attract and retain union grocery workers. To remain competitive, Respondents

monitor and often match each other’s wage increases for union grocery workers.

72. Where Respondents’ union grocery operations overlap, they often negotiate CBAs

separately but simultaneously against local chapters of labor unions representing grocery workers.

During these negotiations, local unions try to play Kroger and Albertsons against each other,

typically by obtaining a favorable deal from one Respondent and then leveraging that deal against

the other Respondent to demand similar or better terms. The local unions can play Respondents

against each other because Respondents closely compete for customers and workers and

Respondents do not want to risk losing either customers or workers to their competitor.

Albertsons’s Vice President of Labor Relations refers to Kroger as its

because Kroger and Albertsons compete for sales and talent while engaging in

bargaining with local unions at the same time. During CBA negotiations with Respondents, the

local unions have been able to improve wages, benefits, and working conditions by leveraging the

competition between Kroger and Albertsons.

73. Union grocery workers’ primary leverage during CBA negotiations is the ability to

credibly threaten a strike. When workers withhold their labor during a strike, workers also

encourage customers to shop at a competing supermarket, preferably another union grocery

employer. Thus, a strike is effective because the employer loses sales and customers to competing

supermarkets. The unions leverage the fact that Kroger and Albertsons compete for customers by

striking or threatening to strike Kroger and encouraging Kroger’s customers to shop elsewhere,

including at Albertsons, and vice versa. Once either Kroger or Albertsons agrees to a certain term

in a union contract, the union can turn to the other firm and threaten a strike if it does not agree to

PUBLIC

-18-

a similar or better term. Kroger’s Vice President of Labor Relations stated during 2022 Seattle

negotiations:

74. UFCW Local 7’s strike against Kroger in Colorado illustrates how the unions play

Respondents off one another during a strike. In January 2022, UFCW Local 7 struck Kroger’s

King Soopers supermarkets in the Denver, Colorado CBA area. Leading up to and during the

strike, Kroger’s union grocery workers encouraged Kroger customers and employees to transfer

their prescriptions to and shop at Albertsons stores instead of Kroger stores.

75. Kroger’s concern about losing customers led them to ask Albertsons

Albertsons’s Senior Vice President of Labor Relations emailed Kroger that

76. During the strike, Kroger lost of dollars in sales and profits, with

Albertsons’s Denver Division

President wrote that Albertsons gained

and

He also noted that Kroger was due to the

strike, which was a for Albertsons.

77. Ultimately, the strike ended when Kroger agreed to improvements to its CBA,

including wage increases and safety protections for its workers. UFCW Local 7 then took the

Kroger agreement to Albertsons, threatening that it would strike Albertsons next. Using this

leverage, UFCW Local 7 got Albertsons to agree to the same wage increases and other important

contract terms like benefits and protections. By striking just Kroger, and encouraging Kroger’s

customers to shop at Kroger’s bargaining competitor, UFCW Local 7 was able to improve the

terms in its CBAs with both employers, leading to improved wages and benefits for thousands of

their members.

78. Executives from both Respondents acknowledge that the unions’ ability to play them

off one another using credible strike threats creates pressure to meet or beat each other’s

PUBLIC

-19-

agreements. This competitive pressure benefits workers at both firms. For example, during the

2022 Denver negotiations with Local 7, Albertsons’s Labor Relations Director expressed this

concern:

79. To counter the unions’ strategy, Respondents have tried to coordinate and align more

closely during negotiations. A 2021 labor strategy white paper prepared for Kroger’s CEO and

other senior leaders recommended that

Similarly, a presentation for Albertsons’s CEO identified

80. To date, Respondents’ coordination efforts have often been unsuccessful. During 2022

negotiations in Southern California, for example, Kroger’s Chief People Officer remarked:

Kroger’s Vice President of Labor

Relations echoed his frustration:

81. Respondents’ lack of alignment during negotiations has led to union contracts with

more favorable salaries and benefits for workers. By contrast, where Kroger and Albertsons have

successfully coordinated, as in Portland negotiations in 2019,

The proposed acquisition is that would allow

Respondents to have total alignment in future negotiations, to the detriment of union grocery

workers.

82. The proposed acquisition would eliminate a competing employer for union grocery

workers and would greatly increase Respondents’ leverage during negotiations with local unions.

With more leverage, the combined Kroger/Albertsons would likely be able to impose terms on

union grocery workers that slow wage increases and improvements to benefits or degrade working

conditions.

VII. LACK OF COUNTERVAILING FACTORS

A. ENTRY WOULD NOT DETER OR COUNTERACT THE ANTICOMPETITIVE

EFFECTS OF THE PROPOSED ACQUISITION

83. Entry into the relevant markets for the retail sale of grocery products in supermarkets

would not be timely, likely, or sufficient in magnitude to deter or counteract the anticompetitive

effects of the proposed acquisition. Significant entry barriers include the time and costs associated

with conducting necessary market research for opening a new supermarket, selecting an

appropriate location for a supermarket, obtaining necessary permits and approvals, negotiating a

lease, constructing a new supermarket or converting an existing structure to a supermarket, and

generating sufficient sales to have a meaningful impact on the market. Additional entry barriers

for supermarket operators without an established presence in a geography include establishing

brand recognition and developing adequate distribution and supply networks to service new stores.

PUBLIC

-20-

84. Timely entry by other union grocery employers is also not likely, and any potential

entry by smaller union grocers would not be sufficient in magnitude to impact negotiations with

the combined Kroger/Albertsons.

B. RESPONDENTS CANNOT DEMONSTRATE EFFICIENCIES SUFFICIENT TO

REBUT THE PRESUMPTION OF HARM

85. Respondents cannot demonstrate merger-specific, verifiable, and cognizable

efficiencies sufficient to rebut the presumption of harm indicated by the proposed acquisition’s

impact on market shares and concentration and the evidence that the proposed acquisition may

eliminate substantial head-to-head competition in the relevant markets.

C. THE PROPOSED DIVESTITURE DOES NOT SUFFICIENTLY MITIGATE THE

LIKELY ANTICOMPETITIVE EFFECTS OF THE PROPOSED ACQUISITION

86. On September 8, 2023, Respondents announced that they intend to divest a hodgepodge

of 413 stores and other castoff assets across 17 states and the District of Columbia to C&S

Wholesale Grocers, LLC.

87. The proposed divestiture does not solve the competitive issues created by the proposed

acquisition. C&S will not acquire an ongoing business operated by either Respondent today in any

geography. In many local markets where Respondents overlap, C&S will not acquire any assets,

leaving local market conditions unchanged. Additionally, in many local markets where C&S is

acquiring stores, Respondents cannot show the proposed divestiture will prevent a substantial

lessening of competition. The proposed divestiture thus does not contain sufficient assets to enable

C&S or any putative acquirer to maintain or replicate the competitive intensity that currently exists

between Kroger’s and Albertsons’s supermarkets, nor will it be able to effectively replace

Albertsons’s position today as a union grocery employer. Thus, the proposed divestiture does not

justify allowing this illegal merger to proceed.

88. The proposed divestiture creates a substantial risk of flawed or failed integration and

operation of the stores for at least three reasons. First, Respondents did not include any full, intact

business units in the proposed divestiture, and the assets included are insufficient to operate a

supermarket business that substantially replaces Kroger or Albertsons. Second, Respondents

structured the proposed divestiture in a way that inextricably entangles Respondents’ and C&S’s

competitive activities for years. Third, Respondents selected a buyer in C&S that is poorly

positioned to operate these stores successfully. The public—not Respondents—would bear the risk

of this failure.

89. Insufficient Assets. The construction of the proposed divestiture package creates a

substantial risk of competitive diminution or outright failure. C&S will operate only approximately

436 supermarkets in total, compared with the approximately 5,000 supermarkets that a combined

Kroger/Albertsons will operate. Respondents did not divest any ongoing business units to C&S.

the proposed divestiture lacks the scale and necessary assets—including

banners, distribution centers, information technology, corporate contracts, loyalty programs,

manufacturing assets, pharmacy resources, data analytics and e-commerce tools, employees, and

others—that Respondents rely on today to successfully operate their respective businesses.

90. C&S will need to construct a brand-new supermarket business on the fly, including

new banner names at over 80 percent of the locations, new private label products, new loyalty

PUBLIC

-21-

programs, and new e-commerce platforms. C&S will need to do that while scrambling to recover

from the loss of numerous assets that Respondents chose not to include in the package

For example, Respondents will not be providing some of Albertsons’s most

popular private label brands, certain self-manufacturing facilities, established data-analytics

capabilities, and experienced regional and corporate support teams. The deficiencies in the

proposed divestiture pose unacceptable risks to competition, consumers, and workers.

91. Anticompetitive Entanglements. The proposed divestiture does not provide any

meaningful relief during a lengthy transition period, as the combined Kroger/Albertsons and C&S

will extensively coordinate on competitively relevant services—including pricing and promotional

activities—for a set transition period.

Thus, the entanglement between

the parties created by the transition plan ties C&S to Respondents in a way that does not

sufficiently mitigate the effects of the proposed acquisition or sufficiently restore the competitive

intensity lost through the merger.

92. Flaws with C&S as Buyer. C&S—a wholesaler with limited supermarket operating

experience—is a poor choice for a divestiture buyer and increases the likelihood that the divested

stores will flounder or fail. C&S operates only 23 Piggly-Wiggly and Grand Union retail

supermarkets and only one retail pharmacy today, most of which C&S acquired in 2021 and 2022.

Due to its lack of experience running a supermarket, C&S requested a call with Kroger during due

diligence C&S previously tried and

failed to operate other supermarkets successfully, even at a much smaller scale than this vast and

complex transaction. Many of the reasons for C&S’s past failures include a complicated

integration of multiple banners, store sizes, and formats and expansion into retail geographies

where C&S has little to no familiarity or retail experience. Each of those concerns are present, if

not compounded, here.

93. As a result of its supermarket retail operating deficiencies and past failures, C&S has

spent most of the last decade seeking to avoid being a supermarket operator. As recently as 2021,

C&S expressly stated in its regularly prepared financial reports: “From time to time, we acquire

retail store locations in connection with strategic transactions to maintain or expand our grocery

wholesaling and distribution business. . . Where possible, we seek to sell these locations to buyers

who are already customers under existing contracts with our grocery wholesaling and distribution

business. We do not intend to grow our grocery retailing operations or to operate the retail grocery

stores in the long term. We expect to divest our retail grocery stores as opportunities arise.” C&S,

Kroger, and Albertsons now claim the opposite—that C&S is a seasoned, well-positioned

supermarket operator that plans to operate the divestiture supermarkets itself into the future.

94. Kroger, Albertsons, and C&S have also claimed that there will be “no store closures,”

but

Tellingly, C&S’s then-CEO, Bob Palmer, shared the following concern to the incoming CEO, Eric

Winn, when reviewing a draft press release touting the commitment: “Do we have to say that we

won’t close stores? (the ‘all’ is a problem) – the trick is that they stay open as they transition but

then what? Are we committed to this?”

95. Furthermore, even if C&S fails to successfully operate the acquired stores, its financial

downside from the proposed divestiture is mitigated due to the value of the real estate assets it is

PUBLIC

-22-

acquiring. In an internal assessment of the proposed divestiture, C&S estimated

The risk of C&S not operating the divested assets successfully falls on the shoulders of the

American consumer far more than those of C&S.

96. Respondents also have a track record of advocating for divestiture remedies that

ultimately prove ineffective, with the public bearing the cost of these failures. Albertsons has done

exactly this twice in the last decade alone—in its 2014 acquisition of United Supermarkets and in

its 2015 acquisition of Safeway.

•

In 2014, Albertsons divested two supermarkets to Lawrence Bros., a regional

chain with 20 supermarkets. Within just five years, Lawrence Bros had closed both

divested supermarkets. Albertsons re-acquired one of the two divestiture stores,

and the other still sits idle. As a result, in neither instance did the divestiture

maintain competition.

•

In 2015, Albertsons proposed selling 168 supermarkets to resolve the competition

concerns with the Safeway acquisition. Those stores were sold to multiple buyers,

including large national/regional wholesale grocers (with existing distribution

systems and some supermarket retail operating experience, albeit more limited

compared to Albertsons). Many stores were also sold to Haggen, a regional Pacific

Northwest chain. Albertsons advocated at the time that the sale of stores to Haggen

would

But the divestitures to Haggen and the other

buyers did not preserve competition, as Albertsons promised. Within a year,

Haggen filed for bankruptcy, most of the divested stores were closed or sold (often

converting to a non-supermarket use), and many workers lost their jobs. Shortly

after Haggen’s failure, Albertsons itself re-acquired 56 of its divested

supermarkets, as well as the remains of the original Haggen chain out of

bankruptcy.

97. In fact, Kroger has proposed to divest to C&S some of the same supermarkets that were

previously divested to other buyers as part of these prior failed remedy attempts. Kroger is only

able to propose re-divesting these supermarkets today because the prior Albertsons-sponsored

remedy attempts failed.

98. Even in the event Kroger changes the divestiture proposal from what it announced last

year, any remaining problems—e.g., lack of complete business units, insufficient and/or mix-and-

matched assets, ongoing entanglements, and flaws with C&S as a buyer—would still create a

substantial risk of flawed or failed integration and operation of the stores. Such a divestiture also

would not sufficiently mitigate this merger’s harms to competition.

VIII. VIOLATIONS

COUNT I – ILLEGAL AGREEMENT

99. The allegations of Paragraphs 1 through 98 above are incorporated by reference as

though fully set forth.

PUBLIC

-23-

100. The proposed acquisition constitutes an unfair method of competition in violation of

Section 5 of the FTC Act, as amended, 15 U.S.C. § 45.

COUNT II – ILLEGAL ACQUISITION

101. The allegations of Paragraphs 1 through 98 above are incorporated by reference as

though fully set forth.

102. The proposed acquisition, if consummated, may substantially lessen competition in

the relevant markets in violation of Section 7 of the Clayton Act, as amended, 15 U.S.C. § 18, and

is an unfair method of competition in violation of Section 5 of the FTC Act, as amended, 15 U.S.C.

§ 45.

NOTICE

Notice is hereby given to the Respondents that the thirty-first day of July, at 10:00 a.m.,

is hereby fixed as the time, and the Federal Trade Commission offices at 600 Pennsylvania

Avenue, N.W., Room 532, Washington, D.C. 20580, as the place, when and where an

evidentiary hearing will be had before an Administrative Law Judge of the Federal Trade

Commission, on the charges set forth in this complaint, at which time and place you will have

the right under the Federal Trade Commission Act and the Clayton Act to appear and show cause

why an order should not be entered requiring you to cease and desist from the violations of law

charged in the complaint.

You are notified that the opportunity is afforded you to file with the Commission an

answer to this complaint on or before the fourteenth (14th) day after service of it upon you. An

answer in which the allegations of the complaint are contested shall contain a concise statement

of the facts constituting each ground of defense; and specific admission, denial, or explanation of

each fact alleged in the complaint or, if you are without knowledge thereof, a statement to that

effect. Allegations of the complaint not thus answered shall be deemed to have been admitted. If

you elect not to contest the allegations of fact set forth in the complaint, the answer shall consist

of a statement that you admit all of the material facts to be true. Such an answer shall constitute a

waiver of hearings as to the facts alleged in the complaint and, together with the complaint, will

provide a record basis on which the Commission shall issue a final decision containing

appropriate findings and conclusions and a final order disposing of the proceeding. In such

answer, you may, however, reserve the right to submit proposed findings and conclusions under

Rule 3.46 of the Commission’s Rules of Practice for Adjudicative Proceedings.

Failure to file an answer within the time above provided shall be deemed to constitute a

waiver of your right to appear and to contest the allegations of the complaint and shall authorize

the Commission, without further notice to you, to find the facts to be as alleged in the complaint

and to enter a final decision containing appropriate findings and conclusions, and a final order

disposing of the proceeding.

The Administrative Law Judge shall hold a prehearing scheduling conference not later

than ten (10) days after the Respondents file their answers. Unless otherwise directed by the

Administrative Law Judge, the scheduling conference and further proceedings will take place at

the Federal Trade Commission, 600 Pennsylvania Avenue, N.W., Room 532, Washington, D.C.

20580. Rule 3.21(a) requires a meeting of the parties’ counsel as early as practicable before the

pre-hearing scheduling conference (but in any event no later than five (5) days after the

PUBLIC

-24-

Respondents file their answers). Rule 3.31(b) obligates counsel for each party, within five (5)

days of receiving the Respondents’ answers, to make certain initial disclosures without awaiting

a discovery request.

NOTICE OF CONTEMPLATED RELIEF

Should the Commission conclude from the record developed in any adjudicative

proceedings in this matter that the Proposed Transaction challenged in this proceeding violates

Section 5 of the Federal Trade Commission Act, as amended, and/or Section 7 of the Clayton

Act, as amended, the Commission may order such relief against Respondents as is supported by

the record and is necessary and appropriate, including, but not limited to:

1. A prohibition against any transaction between The Kroger Company and

Albertsons Companies, Inc. that combines their businesses, except as may be

approved by the Commission.

2. If the Proposed Transaction is consummated, divestiture or reconstitution of all

associated and necessary assets, in a manner that restores two or more distinct and

separate, viable and independent businesses in the relevant market, with the

ability to offer such products and services as The Kroger Company and

Albertsons Companies, Inc. were offering and planning to offer prior to the

Proposed Transaction.

3. A requirement that, for a period of time, The Kroger Company and Albertsons

Companies, Inc. provide prior notice to and receive prior approval from the

Commission for acquisitions, mergers, consolidations, or any other combinations

of their businesses in the relevant market with any other company operating in the

relevant market.

4. A requirement to file periodic compliance reports with the Commission.

5. Requiring that Respondents’ compliance with the order may be monitored at

Respondents’ expense by an independent monitor, for a term to be determined by

the Commission.

6. Any other relief appropriate to correct or remedy the anticompetitive effects of the

Proposed Transaction or to restore The Kroger Company and/or Albertsons

Companies, Inc. as viable, independent competitors in the relevant market[s].

IN WITNESS WHEREOF, the Federal Trade Commission has caused this complaint to be

signed by its Secretary and its official seal to be hereto affixed, at Washington, D.C., this twenty-

sixth day of February, 2024.

By the Commission.

April J. Tabor

Secretary

SEAL: