Lyme and Other

Tickborne Illnesses

2022 Annual Report

Submitted to the Joint Standing Committee on Health and

Human Services

Prepared by:

Division of Disease Surveillance

Maine Center for Disease Control and Prevention

Maine Department of Health and Human Services

Maine CDC Report to Maine Legislature on Lyme Disease - 2023

1

Introduction and Background

In 2008, during the first special session of the 123

rd

Legislature, hearings and discussion over proposed

legislation regarding the reporting of Lyme disease led to Public Law 2007 Chapter 561. This law, An Act to

Implement the Recommendations of the Joint Standing Committee on Insurance and Financial Services

Regarding Reporting on Lyme Disease and Other Tickborne Illnesses, directed Maine Center for Disease

Control and Prevention (Maine CDC) to submit an annual report to the joint standing committee of the

Legislature having jurisdiction over health and human services matters and the joint standing committee of

the Legislature having jurisdiction over health insurance matters. This annual report is to include

recommendations for legislation to address public health programs for the prevention and treatment of Lyme

disease and other tickborne illnesses in the State, as well as to address a review and evaluation of Lyme

disease and other tickborne illnesses in Maine.

22 MRS, chapter 266-B, was further amended by emergency legislation, introduced as LD 1709 in the 124

th

Legislature, to require the Maine CDC to include information on diagnosis of Lyme disease in its annual

report and to publish related information on its public website.

22 MRS §1645, directs Maine CDC to report on:

1. The incidence of Lyme disease and other tickborne illness in Maine;

2. The diagnosis and treatment guidelines for Lyme disease recommended by Maine Center for Disease

Control and Prevention and the United States Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for

Disease Control and Prevention;

3. A summary or bibliography of peer-reviewed medical literature and studies related to the

surveillance, diagnosis, medical management, and treatment of Lyme disease and other tickborne

illnesses, including, but not limited to, the recognition of chronic Lyme disease and the use of long-

term antibiotic treatment;

4. The education, training, and guidance provided by Maine Center for Disease Control and

Prevention to healthcare professionals on the current methods of diagnosing and treating Lyme

disease and other tickborne illnesses;

5. The education and public awareness activities conducted by Maine Center for Disease Control and

Prevention for the prevention of Lyme disease and other tickborne illnesses; and

6. A summary of the laws of other states enacted during the last year related to the diagnosis, treatment,

and insurance coverage for Lyme disease and other tickborne illnesses based on resources made

available by the federal Centers for Disease Control and Prevention or other organizations.

This is the fourteenth annual report to the Legislature and includes an update on activities conducted during 2022.

Maine CDC Report to Maine Legislature on Lyme Disease - 2023

2

Executive Summary

Lyme disease is a notifiable condition in the State of Maine and, as such, must be reported to the Maine

Center for Disease Control and Prevention (Maine CDC), in accordance with 10-144 CMR chapter 258. The

goal of Lyme disease surveillance is to help define demographic, geographic, and seasonal distribution;

monitor disease trends; identify risk factors for transmission; and promote prevention and education efforts

among the public and medical communities. Effective January 2, 2022, the Council of State and Territorial

Epidemiologists (CSTE) modified the Lyme disease surveillance case definition. Under the new definition,

Maine CDC no longer collects reports of erythema migrans (bull’s-eye) rashes or clinical information on

positive laboratory results from healthcare providers. As a result, Maine CDC epidemiologists classify

reported cases as probable, suspect, and not a case based on laboratory results alone, without the information

on clinical symptoms required under the previous surveillance case definition. Maine CDC no longer reports

confirmed cases of Lyme disease, in line with the CSTE definition. The surveillance case definition is not

intended to be used in clinical diagnosis. Lyme disease surveillance is passive, dependent upon reporting, and

therefore likely to be an under-representation of the true burden of Lyme disease in Maine. Federal CDC

released an updated statement in 2021 that the true burden of Lyme disease may be more than ten times the

number of reported cases. In 2022, federal CDC estimated that the aggregate cost of diagnosed Lyme disease

alone could be $345-968 million to U.S. society.

Maine Tickborne Disease Summary, 2022

●

2,617 probable cases of Lyme disease (preliminary data as of March 8, 2023)

●

824 confirmed and probable cases of anaplasmosis (preliminary data as of March 8, 2023)

●

192 confirmed and probable cases of babesiosis (preliminary data as of March 8, 2023)

●

12 confirmed and probable cases of Hard Tick Relapsing Fever (preliminary data as of March 8, 2023)

●

4 confirmed and probable cases of Powassan virus disease (preliminary data as of March 8, 2023)

* 2022 data are preliminary as of 03/08/2023

Maine CDC Report to Maine Legislature on Lyme Disease - 2023

3

1. The incidence of Lyme disease and other tickborne illness in Maine

Lyme disease

Lyme disease is caused by the spiral-shaped bacteria Borrelia burgdorferi, and, in rare cases, by Borrelia

mayonii, which are both transmitted to humans through the bite of an infected deer or blacklegged tick (Ixodes

scapularis). Symptoms of Lyme disease caused by B. burgdorferi include the formation of a characteristic

expanding rash (erythema migrans) that usually appears three to 30 days after exposure and may appear on any

area of the body. Fever, headache, joint and muscle pains, and fatigue are also common during the first several

weeks. Later features of Lyme disease can include arthritis in one or more joints (often the knee), facial palsy,

meningitis, and carditis (AV block). Lyme disease is rarely fatal. The great majority of Lyme disease cases can

be treated very effectively with oral antibiotics for ten days to a few weeks. Some cases of Lyme disease which

affect the nervous system, joints, or heart may need intravenous antibiotics for up to 28 days.

In 2013, scientists at the Mayo Clinic discovered B. mayonii while testing blood from patients thought to have

Lyme disease with B. burgdorferi infection. Instead, they found a new bacterium that is also transmitted by

deer ticks. Currently, B. mayonii is only found in the Upper Midwest and is not thought to infect ticks in

Maine. Borrelia mayonii causes a similar illness to B. burgdorferi, but can also cause nausea and vomiting;

large, widespread rashes; and a higher concentration of bacteria in the blood. Lyme disease caused by B.

mayonii can be diagnosed with the same tests used to identify Lyme disease due to B. burgdorferi infection

and treated with the same antibiotics.

In the United States, the highest rates of Lyme disease occur across the eastern seaboard (Maryland to Maine)

and in the upper Midwest (Wisconsin and Minnesota), with the onset of most cases occurring during the

summer months. Where they are endemic, deer ticks are most abundant in wooded, leafy, and brushy areas

(“tick habitat”), especially where deer populations are large.

Reported Cases of Lyme Disease – United States, 2020

1 dot placed randomly within county of residence for each confirmed case. High

incidence states highlighted in light blue. Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, 2020

data from some jurisdictions may be incomplete.

Source: U.S. CDC (www.cdc.gov/lyme/datasurveillance/index.html)

Maine CDC Report to Maine Legislature on Lyme Disease - 2023

4

Through 2021, many endemic states no longer count cases of Lyme disease as the burden is too great on the

health department. This affects the national and regional rates as the number of cases appears to drop, though

this is really the result of these health departments using a system to estimate the number of cases rather than

counting each individual case.

Effective January 2, 2022, the Council of State and Territorial Epidemiologists (CSTE) modified the Lyme

disease surveillance case definition. Under the previous surveillance definition, Maine CDC followed up with

healthcare providers to collect corresponding clinical information for every laboratory report received before

the case could be classified as confirmed, probable, suspect, or not a case. Reported erythema migrans rashes

with likely exposure in a state with high Lyme disease incidence were automatically classified as confirmed

cases. Under the new surveillance definition, Maine CDC no longer collects reports of erythema migrans

rashes or clinical information on positive laboratory results from healthcare providers. As a result, Maine CDC

reports cases that meet laboratory evidence alone, without needing healthcare providers to report clinical

information, and no longer reports confirmed cases of Lyme disease, only probable.

Under the new surveillance definition, Lyme disease case counts may increase by 50-100% compared to

previous years under the old surveillance definition (including 2021 case data) (Kugeler et al. 2022). Under the

previous case definition, epidemiologists classified Lyme disease lab reports as confirmed or probable if the

healthcare provider returned the case report form with clinical information for the patient. As healthcare

providers in Maine only returned these reporting forms approximately 50% of the time, epidemiologists

classified lab results lacking this clinical information as suspect cases. The number of confirmed and probable

Lyme disease cases reported by Maine CDC likely underrepresented the true number of cases that could be

classified as confirmed or probable as a result. Under the new case definition, Lyme disease cases are classified

by lab results alone, without needing corresponding clinical information from healthcare providers, reducing

the number of labs that remained uncounted due to failure of healthcare providers to report clinical information.

The first documented case of Maine-acquired Lyme disease was diagnosed in 1986. In the 1990s, the great

majority of Lyme disease cases occurred among residents of south coastal Maine, principally in York County.

Currently, the Midcoast and Downeast areas have the highest incidence of Lyme disease in the State. Based on

2022 data, seven counties have rates of Lyme disease higher than the State rate (Hancock, Knox, Lincoln,

Sagadahoc, Somerset, Waldo, and Washington).

In 2022, (preliminary data as of March 8, 2023) providers reported 2,617 probable cases of Lyme disease

among Maine residents, which is a rate of 188.9 cases of Lyme disease per 100,000 persons in Maine. This is

a 73% increase from the 1,129 cases in 2021. Twenty-nine percent (29%) of reported cases were from the

Midcoast counties (Knox, Lincoln, Sagadahoc, and Waldo) and 17% were from the Downeast counties

(Hancock and Washington).

Forty-three percent (43%) of cases were female and 57% of cases were male. The median age of cases in 2022

was 59 years of age (average age of 52 years). The age at diagnosis ranged from less than 1 to 100 years of

age. For further Lyme disease statistics in Maine, please see Appendix 1.

Maine CDC Report to Maine Legislature on Lyme Disease - 2023

5

Other tickborne diseases in Maine

Anaplasmosis:

Anaplasmosis is a disease caused by the bacterium Anaplasma phagocytophilum, which infects white blood

cells (neutrophils). Anaplasmosis was previously known as human granulocytic ehrlichiosis (HGE) or human

granulocytic anaplasmosis (HGA) but was renamed in 2008 to differentiate between two different organisms

that cause similar diseases (anaplasmosis and ehrlichiosis). Signs and symptoms of anaplasmosis include fever,

headache, malaise, and body aches. Nervous system involvement may occur but is rare. Later features of

anaplasmosis can include respiratory failure, bleeding problems, organ failure, and death. Anaplasmosis is

transmitted to a person through the bite of an infected deer tick. As of March 8, 2023, Maine reported 824

confirmed and probable cases of anaplasmosis in 2022, a 2% decrease from the 841 cases in 2022. Cases

occurred in every county in Maine. For further anaplasmosis disease statistics in Maine, please see Appendix 2.

Babesiosis:

Babesiosis is a potentially severe tickborne disease transmitted through the bite of an infected deer tick. Signs

of babesiosis range from no symptoms (asymptomatic) to serious disease. Common symptoms include extreme

fatigue, aches, fever, chills, sweating, body aches, dark urine, and anemia. People who are infected generally

make a full recovery if they have a healthy spleen and do not have other diseases that prevent them from

fighting infections. As of March 8, 2023, Maine reported 192 confirmed and probable cases of babesiosis in

2022, a 4% decrease from the 201 cases in 2022. Cases occurred in every county except Aroostook and

Piscataquis. For further babesiosis disease statistics in Maine please see Appendix 2.

Hard Tick Relapsing Fever:

Hard Tick Relapsing Fever (HTRF), previously referred to as Borrelia miyamotoi disease, is caused by a

species of spiral-shaped bacteria, called B. miyamotoi, that is closely related to the bacteria that causes

tickborne relapsing fever (TBRF). It is more distantly related to the bacteria that causes Lyme disease. First

identified in 1995 in ticks from Japan, two species of North American ticks carry B. miyamotoi, the deer tick

and the western blacklegged tick (Ixodes pacificus). Common symptoms include fever, chills, headache, joint

pain, and fatigue. Although HTRF is not nationally notifiable, U.S. CDC, in association with endemic states,

developed a case classification to standardize reporting and understand the prevalence in the United States.

Hard Tick Relapsing Fever (Borrelia miyamotoi disease) is a notifiable condition in Maine. As of March 8,

2023, Maine reported 12 probable or confirmed cases of HTRF in 2022 in Maine. Cases occurred in

Androscoggin, Cumberland, Hancock, Kennebec, Knox, Lincoln, Penobscot, Sagadahoc, and York counties.

For further HTRF statistics in Maine, please see Appendix 2.

Ehrlichiosis:

Ehrlichiosis is a disease caused by the bacteria Ehrlichia chaffeensis and Ehrlichia ewingii which infect white

blood cells (monocytes and granulocytes). In the United States, most cases are caused by E. chaffeensis.

Ehrlichiosis was previously known as human monocytic ehrlichiosis (HME). Signs and symptoms of

ehrlichiosis include fever, headache, nausea, and body aches. A rash may

Maine CDC Report to Maine Legislature on Lyme Disease - 2023

6

develop, especially in children. Severe illness, especially when treatment is delayed, may include

encephalitis/meningitis, kidney failure, and liver failure. Ehrlichia chaffeensis and E. ewingii are transmitted to

a person through the bite of an infected lone star tick (Amblyomma americanum). Ehrlichiosis is uncommon in

Maine as this tick is not commonly found here. However, as lone star tick populations continue to creep

northward, this disease may become more common in Maine in the future. At present, most cases detected in

Maine are due to exposure to infected ticks during travel to an endemic state. As of March 8, 2023, Maine

reported seven probable cases of ehrlichiosis in 2022 from Androscoggin, Kennebec, Knox, and Lincoln

counties. Maine had one report of Ehrlichia/Anaplasma Undetermined in 2022, which occurs when serologic

testing results in titers that are the same for both Ehrlichia and Anaplasma, making it impossible to determine

which organism was present. For further ehrlichiosis disease statistics in Maine please see Appendix 2.

Powassan virus disease:

Powassan virus disease is caused by either the Powassan virus or deer tick virus, which are transmitted to

humans through the bite of an infected woodchuck tick (Ixodes cookei) or deer tick, respectively. Signs and

symptoms of Powassan virus disease include fever, headache, vomiting, weakness, confusion, seizures, and

memory loss. Long-term neurologic problems may occur. As of March 8, 2023, Maine reported four

confirmed case of Powassan encephalitis in Maine in 2022. This is a record number of Powassan virus

diseases cases in Maine. These cases occurred in Cumberland, Penobscot, Waldo, and York counties.

Spotted fever rickettsiosis:

Spotted Fever Rickettsioses (SFR) are a group of bacterial illnesses, the most common of which is Rocky

Mountain Spotted Fever (RMSF), caused by the bacterium Rickettsia rickettsii. Signs and symptoms of RMSF

include fever, chills, headache, gastrointestinal symptoms, and a non-itchy spotted rash (called maculopapular)

often on the palms and the soles of the feet. Other spotted fever rickettsioses show similar symptoms,

including fever, headache, and rash, and may also feature a dark scab at the site of the tick bite (known as an

eschar). Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever is transmitted to a person through the bite of an infected American dog

tick (Dermacentor variabilis) in most of the U.S. Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever is not known to be endemic

in Maine but could emerge, as American dog ticks are commonly found across the state. As of March 8, 2023,

Maine reported one probable case of SFR in 2022. This case occurred in Lincoln County. For further SFR

disease statistics in Maine please see Appendix 2.

Other emerging tickborne diseases:

U.S. CDC and other researchers are continually on the watch for new or emerging tickborne diseases.

Pathogens emerging in the United States include Bourbon virus, Colorado Tick Fever virus, Heartland virus,

and Ehrlichia muris eauclairensis. While Maine has no documented cases of any of these diseases, there is

serological evidence from whitetail deer of Heartland virus in Maine. Several of these pathogens are transmitted

by ticks that already live in Maine or may move into Maine in the future, so Maine CDC monitors these

pathogens.

Additionally, the Asian Longhorn tick, Haemaphysalis longicornis, which was reported in the U.S. for the

first time in 2017, has been spreading. Already documented in 17 states, the Asian Longhorn tick has been

found in Connecticut, Rhode Island, New York, and Massachusetts, and may find its way to Maine. Though,

compared with other ticks in Maine, the Asian Longhorn tick seems to be less attracted to humans, it has

been found on pets, livestock, wildlife, and humans. In other countries,

Maine CDC Report to Maine Legislature on Lyme Disease - 2023

7

this tick can spread pathogens that make people and animals very sick. Research is ongoing to find out if and

how well these ticks can spread pathogens that cause diseases in the US like Lyme disease, anaplasmosis, and

babesiosis. Maine CDC monitors this research and regional surveillance for the Asian Longhorn tick.

2. The diagnosis and treatment guidelines for Lyme disease recommended by Maine Center for Disease

Control and Prevention and the United States Department of Health and Human Services, Centers

for Disease Control and Prevention

Maine CDC continues to adhere to the strongest science-based source of information for the diagnosis and

treatment of any infectious disease of public health significance. Nationally, the Infectious Disease Society of

America (IDSA) is the leader in setting the standard for clinical practice guidelines on Lyme disease and other

tickborne illnesses.

Lyme disease is diagnosed clinically with the aid of laboratory testing. An erythema migrans (bull’s- eye rash)

on a person from an endemic area is distinctive enough to allow a clinical diagnosis in the absence of

laboratory confirmation. Patients should be treated based on clinical findings. Either a standardized or modified

two-tier testing algorithm (STTT or MTTT, respectively) is recommended for laboratory testing. With STTT,

the first tier includes an enzyme immunoassay (EIA) or immunofluorescence assay (IFA). If this first tier is

positive or equivocal, an IgM and/or IgG Immunoblot follows. The IgM Immunoblot is only considered

reliable if the person is tested within the first 30 days after symptom onset. With MTTT, the first tier uses an

EIA, similar to STTT. If positive or equivocal, a second EIA follows. Acute and convalescent testing, or testing

run on samples collected during illness and after recovery, is useful to determine final diagnosis. Providers

should consider other potential diagnoses for untreated patients who remain seronegative despite having

symptoms for 6-8 weeks, as they are unlikely to have Lyme disease. A diagnosis of Lyme disease made by a

clinician may or may not meet the federal surveillance case definition, and therefore may not always be

counted as a case.

Maine CDC refers physicians with questions about diagnosis to the IDSA guidelines:

www.idsociety.org/practice-guideline/lyme-disease/.

In 2015, IDSA convened a panel to assess and update guidelines for the treatment and prevention of Lyme

disease and other tickborne diseases. The results from this panel were published in the 2020 Lyme disease

guidelines found at www.idsociety.org/practice-guideline/lyme-disease/. This panel affirmed “the term ‘chronic

Lyme disease’ as currently used lacks an accepted definition for either clinical use or scientific study.”

Currently, U.S. CDC recognizes Post-Treatment Lyme Disease Syndrome (PTLDS), defined as symptoms of

pain, fatigue, or difficulty thinking that lasts for more than 6 months after completion of Lyme disease

treatment (https://www.cdc.gov/lyme/postlds/index.html). There is no proven treatment for PTLDS, but U.S.

CDC notes that patients with PTLDS usually get better over time, though this may take many months. The

2015 panel also noted “[Studies] of persistent symptomatology after treatment of verified Lyme disease have

found that prolonged antimicrobial therapy is not helpful and may cause harm. From this, one can infer that

prolonged antibiotic treatment is unlikely to benefit individuals who lack a verifiable history of Lyme disease

while exposing them to significant risk.”

Maine CDC Report to Maine Legislature on Lyme Disease - 2023

8

3. A Summary or bibliography of peer reviewed medical literature and studies related to the surveillance,

diagnosis, medical management, and the treatment of Lyme disease and other tickborne illnesses,

including, but not limited to, the recognition of chronic Lyme disease and the use of long-term antibiotic

treatment

A bibliography of peer reviewed journal articles published in 2022, as related to surveillance, diagnostics,

medical management, treatment, and other topics relevant in Maine for Lyme and other tickborne illnesses is

included in Appendix 3. Maine CDC reviews these journal articles to maintain an understanding of the current

research and literature available on Lyme and other tickborne diseases.

4. The education, training, and guidance provided by Maine Center for Disease Control and Prevention

to healthcare professionals on the current methods of diagnosing and treating Lyme disease and other

tickborne illnesses

Maine CDC continues to emphasize prevention and control of Lyme disease and other tickborne diseases.

Surveillance for tickborne diseases, including Lyme disease, is performed by the Division of Disease

Surveillance, Infectious Disease Epidemiology Program, as anaplasmosis, babesiosis, ehrlichiosis, Hard Tick

Relapsing Fever (B. miyamotoi disease), Lyme disease, Powassan virus disease, and spotted fever rickettsiosis

are notifiable diseases by both medical practitioners and clinical laboratories. Reporting clinicians must submit

subsequent clinical and laboratory information following the initial report. Maine CDC also monitors tickborne

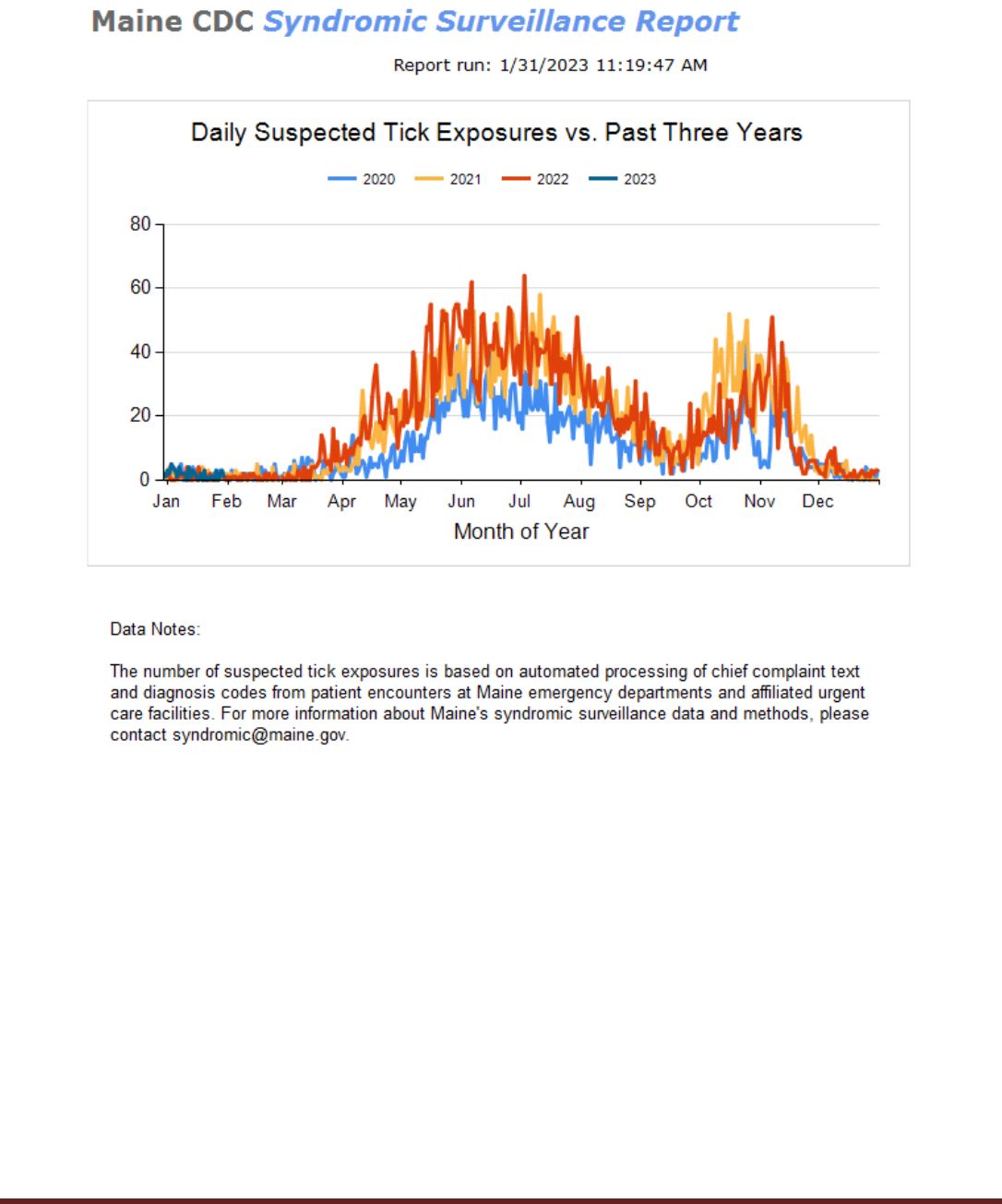

diseases through syndromic surveillance. By querying participating hospital emergency department (ED) patient

visit data, patients that complain of a tick bite are identified. An increase in ED visits for tick bites is usually a

precursor for the typical seasonal increase in incidences of Lyme and other tickborne diseases. A comparison of

2020, 2021, and 2022 syndromic data is included as Appendix 4. Maine CDC performed a spatial analysis of

2022 Lyme disease surveillance data at the county level, showing the geographic spread of the disease in Maine

(Appendix 5).

Outreach and education to clinicians and other healthcare providers is ongoing. Maine CDC epidemiologists

provide consultation to the medical community on tickborne diseases, offering educational and preventive

information as needed. Maine CDC epidemiologists present educational outreach activities and seminars on

tickborne disease prevention targeting the medical community at statewide meetings of school nurses and

others, though the majority of these efforts were conducted virtually in 2022 due to the ongoing COVID-19

response and staffing shortages. Ongoing educational initiatives are featured on the Maine CDC website:

www.maine.gov/lyme.

During 2022, Maine CDC Infectious Disease Epidemiology Program mailed a clinical management guide,

“Tickborne Diseases of the United States: A Reference Manual for Healthcare Providers,” to hospitals, urgent

care providers, and dermatologists. This guide includes information on ticks found in the US and

signs/symptoms, laboratory services, diagnosis, and treatment of twelve tickborne diseases, including Lyme

disease.

●

Maine CDC distributed 172 copies of this guide in 2022

Maine CDC continues to contribute to national surveillance and prevention activities, though these

activities were hampered by ongoing staffing shortages. During 2022, Maine CDC epidemiologists

represented the State at national and regional meetings:

●

CDC Vector Week Conference on Zoom in January 2022

●

Connecticut Agricultural Experiment Station Vectorborne Disease Symposium on Zoom in May 2022

●

Council of State and Territorial Epidemiologists (CSTE) Annual Conference in Louisville, Kentucky in June

2022

Maine CDC Report to Maine Legislature on Lyme Disease - 2023

9

●

CDC Lyme Disease High-Incidence States Meeting on Zoom in October 2022

●

Northeast Epidemiology Conference on Zoom in November 2022

●

Northeast Mosquito Control Association Annual Meeting on Zoom in December 2022

●

Northeast Regional Center for Excellence in Vectorborne Diseases Arbovirus Situational Awareness Calls

(weekly from summer through fall)

●

USDA National Asian Longhorned Tick Stakeholder Calls (monthly throughout year)

●

National Association of Vectorborne Disease Control Officials (NAVCO) Board Meetings

●

NAVCO Regional Calls (throughout the year)

●

NAVCO Membership Calls (throughout the year)

Maine Epidemiologists are active contributors in federal working groups on:

●

Alpha-gal allergy

●

Anaplasmosis

●

Borrelia miyamotoi (Hard Tick Relapsing Fever)

●

Vectorborne diseases

5. The education and public awareness activities conducted by Maine Center for Disease Control and

Prevention for the prevention of Lyme disease and other tickborne illnesses

Maine CDC promotes ongoing educational outreach activities targeting the public and Maine municipalities.

During 2022, Maine CDC epidemiologists provided consultation to the public on tickborne diseases, offering

educational and preventive information as needed. Maine CDC epidemiologists presented educational outreach

activities and seminars on tickborne disease prevention to the general public including:

●

Three presentations or displays held for businesses and community members.

●

Five media interviews given by Maine CDC employees (Infectious Disease Epidemiology Program

Director and Vectorborne Disease Health Educator).

Maine CDC’s Infectious Disease Epidemiology Program Director chairs the State Vectorborne Disease Work

Group; a group comprising both state agencies and private entities, which meets on a bimonthly basis to

proactively address surveillance, prevention, and control strategies. Members of this group include Maine

Department of Health and Human Services; Maine Department of Agriculture, Conservation, and Forestry;

Maine Department of Inland Fisheries and Wildlife; Maine Department of Education; Maine Department of

Environmental Protection; Maine Forest Service; University of Maine Cooperative Extension Services; and the

United States Department of Agriculture. A full list of members can be found in Appendix 6. Educational

efforts by the Vectorborne Work Group in 2022 included:

●

Presentations given on ticks and tickborne diseases

●

Presence in radio and television interviews

●

Distribution of educational materials including Lyme brochures, tick spoons, fact sheets, etc.

●

Formation of a Vector Control District subcommittee to discuss the feasibility and creation of vector control

districts in Maine.

In 2014, Maine CDC created an educational curriculum aimed at teaching students in 3

rd

to 8

th

grade about

tick biology and ecology, tickborne diseases, and tick prevention. The program consists of a twenty-minute

PowerPoint presentation on tick biology and ecology, and tickborne disease information; four ten-minute

interactive activities; and a take-home packet with games, activities, and information for parents.

Maine CDC Report to Maine Legislature on Lyme Disease - 2023

10

In 2022, after the end of the grant cycle that had previously funded the above-mentioned curriculum activities,

Maine CDC shifted focus to maintaining the tickborne disease curriculum. Maine CDC worked with Maine

DOE to distribute the remaining unused stock of physical curriculum materials to interested school nurses and

administrators throughout the state. This resulted in an additional 14 schools in Maine receiving all of the

materials needed to implement the curriculum. Maine CDC plans to review and update the curriculum on the

school curriculum webpage (www.maine.gov/dhhs/schoolcurricula) as needed in 2023.

Educational materials for the 3

rd

-8

th

graders are available online, including an educator’s guide, group

activities, and activity book for both ticks and mosquitoes. Maine CDC included activities and materials in

formats that are useful for distance learning to accommodate a variety of approaches that educators may use for

in-person or virtual settings. Maine CDC continues to review and update the educational materials. Maine

CDC’s interactive workbook called “Take Back Your Yard! A workbook for kids to fight the bite!” is also

available with the curriculum. This workbook is designed for students in 3

rd

-5

th

grades to work with an adult

parent/guardian to identify and remove tick and mosquito habitat around their homes to prevent vectorborne

diseases. Educational materials are available at the following link: www.maine.gov/dhhs/schoolcurricula. As

requested, Maine CDC also makes curriculum materials available for other local, state, and country agencies to

use for tickborne disease education. In 2022, New York City Department of Health reached out to Maine CDC

for permission to reuse parts of the Maine CDC tickborne disease curriculum in a pilot project planned for 2023.

●

The school curriculum webpage (www.maine.gov/dhhs/schoolcurricula) recorded 609 unique

pageviews in 2022.

Maine CDC ran a Social Media Campaign May through July 2022. In previous years, this campaign consisted

of advertisements on YouTube and Facebook, however, the grant cycle that funded those efforts ended prior to

2022. In 2022, Maine CDC produced a campaign that consisted of a series of static ads and short videos on

Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter. Maine CDC added a total of five new social media static ads produced with

a graphic designer to the 2022 social media campaign. These static ads focused on tick identification,

recognition of different life stages of the deer tick (especially nymphs and adults), and EM rash (bull’s-eye

rash) recognition on different anatomical sites and on different skin tones.

Reach and engagement during the campaign include:

●

Facebook (20 Total Posts in Campaign)

○

Total Reach for Campaign: 322,108 (range 79-59,140 per post)

○

Total Post Engagements for Campaign (reactions, link clicks, comments, and shares): 5,031 (range 15-

1,250 per post)

●

Instagram (17 Total Posts in Campaign)

○

Total Reach for Campaign: 8,315 (range 206-1,670 per post)

○

Total Post Engagements for Campaign (reactions, comments, and shares): 198 (range 1-48 per post)

●

Twitter (20 Total Posts in Campaign)

○

Total Reach for campaign: 15,342 (range 432-1,348 per post)

○

Total Post Engagements for Campaign (likes, link clicks, retweets, replies, etc.): 579 (range 6-100 per

post)

Maine CDC maintains a series of short instructional videos to educate the Maine community in tick

prevention and tickborne diseases. All of the instructional videos are available at

www.youtube.com/MainePublicHealth. These videos include:

●

Choosing and Applying Personal Repellents – viewed 29 times in 2022

●

Do You Know Who’s Most at Risk for Lyme Disease – viewed 6 times in 2022

●

How to Choose a Residential Pesticide Applicator – viewed 27 times in 2022

●

How to Perform a Tick Check – viewed 1,196 times in 2022

●

Know How to do Tick Checks – viewed 190 times in 2022

Maine CDC Report to Maine Legislature on Lyme Disease - 2023

11

●

Know How to Prevent Tick Bites – viewed 42 times in 2022

●

Know How to Remove Ticks – viewed 42 times in 2022

●

Reducing Tick Habitat Around Your Home- viewed 120 times in 2022

●

Tick Identification – viewed 1,330 times in 2022

●

Tickborne Diseases in Maine: Anaplasmosis – viewed 562 times in 2022

●

Tickborne Diseases in Maine: Babesiosis – viewed 50 times in 2022

●

Tickborne Diseases in Maine: Lyme Disease-viewed 22 times in 2022

●

Tickborne Diseases: Powassan Encephalitis– viewed 123 times in 2022

Maine CDC’s Lyme disease website is continually updated to provide information to the public and to health

professionals about Lyme disease in Maine. As part of an ongoing effort to review and update Maine CDC

webpages, Maine CDC reviewed and updated the vectorborne disease homepage

(www.maine.gov/dhhs/vectorborne), as well as webpages for seven of the eight endemic vectorborne diseases

in Maine. In 2022:

●

The Lyme disease homepage (www.maine.gov/lyme) received 2,682 unique pageviews.

●

The tick frequently asked questions homepage (www.maine.gov/dhhs/tickfaq) received 1,952 unique

pageviews.

Ongoing educational initiatives featured on Maine CDC’s website include:

●

Anaplasmosis, babesiosis, Ehrlichiosis, Hard Tick Relapsing Fever (Borrelia miyamotoi), Lyme

disease, Powassan virus disease, and Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever fact sheets

●

Tickborne frequently asked questions with peer-reviewed citations

●

Tick identification resources

●

Tick bite and tickborne disease prevention methods

●

Lyme disease, anaplasmosis, ehrlichiosis, and babesiosis Surveillance Reports, selected years

from 2008-2021

●

Vectorborne disease school curricula

●

Maine Tracking Network: Tickborne Diseases

●

Tickborne Diseases in Maine webinar updated annually

During 2022, Maine CDC distributed Lyme disease educational materials to partners and members of the

public. After the close of the grant cycle that funded the bulk of educational material production and distribution

in 2022, Maine CDC will limit the availability of certain materials for public order. This includes tick remover

spoons, which Maine CDC previously offered for order by members of the public and businesses. Going

forward, Maine CDC will reserve the remaining stock of tick spoons for distribution at educational events.

Maine CDC will continue to make all printed materials available for download. Approximate numbers of

materials distributed include:

●

10,417 Wallet-sized laminated tick identification cards

●

16,852 Tick remover spoons

●

953 Lyme disease brochures

●

798 Tick ID posters

●

1,021 What to Do after a Tick Bite posters

●

155 Lyme Disease Awareness Month 2021 posters

●

300 Lyme Disease Awareness Month 2022 posters

●

172 Tickborne Diseases in the United States: A Reference Manual for Healthcare Providers

●

1,754 Prevent Tickborne Diseases bookmark

●

720 Prevent Tickborne Diseases in People and Pets bookmark

●

71 Prevent Tick Bites trail sign

Maine CDC Report to Maine Legislature on Lyme Disease - 2023

12

Members of the Vectorborne Disease Working Group assist Maine CDC in distributing educational materials as

widely as possible throughout the State.

Maine CDC releases Health Alerts (www.maine.gov/dhhs/mecdc/all-health-advisories.shtml), press releases, and

other information on disease concerns of public health significance, including tickborne diseases. Maine CDC also

responds to numerous press inquiries and releases press statements as appropriate. Official releases in 2022 included:

●

Maine CDC Confirms Fatal Case of Powassan Virus in Waldo County (Press Release) – April 20

th

●

2022 Lyme and Other Tickborne Disease Information (Health Alert) – May 9

th

●

Maine CDC Marks Lyme Disease Awareness Month (Press Release) – May 9

th

●

Maine CDC Congratulates 2022 Lyme Disease Awareness Month Poster Contest Winners (Press Release) –

May 19

th

●

Arbovirus Update for Healthcare Providers (Health Alert) – August 3

rd

●

Maine CDC Shares Advice on Home to Avoid Tick Bites This Fall (Press Release) – September 29

th

Pursuant to legislation enacted in the second regular session of the 124

th

Legislature, May 2022 was declared to

be Lyme Disease Awareness Month (PL 2009, chapter 494). Educational activities took place the entire

month including:

• Governor’s Proclamation of Lyme Disease Awareness Month (Appendix 7)

• Information distributed through social media (Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter)

• Information distributed through multiple newsletters throughout the state (medical, veterinary, and other general

interest)

• Information distributed through multiple media interviews across the State of Maine

• Educational tabling event at LL Bean in Freeport, Maine

Another major Lyme Disease Awareness Month activity was the statewide poster contest for students in

grades K-8. Maine CDC asked students to create a poster with the theme “Tick Wise” demonstrating at least

one of the four Lyme disease prevention methods (wear protective clothing, use repellent, use caution in tick

infested areas, and perform daily tick checks). The four winning posters and one honorable mention poster are

available for viewing at the Lyme disease website: www.maine.gov/lyme. Maine CDC used one of the

winning posters for our 2022 statewide educational campaign (Appendix 8). Maine CDC distributed this

poster to schools, state parks, the board of tourism, and historical sites. An online poster gallery of all

artworks submitted over the past thirteen years is available for viewing on Maine CDC’s Lyme Disease

Awareness Month website: www.maine.gov/lyme/month.

In 2012, Maine CDC updated Lyme disease data on the Maine Tracking Network (MTN) Portal, a web-

based portal that allows users to access environmental and health data. In 2018, the Maine Tracking Network

added anaplasmosis and babesiosis data to the Lyme disease portion of the portal. This data portal allows users

to customize their data inquiries from 2001-2020 at the town, county, and state level, and 2021-2023 data

inquiries at the county and state level. The Tickborne Disease portion of the portal was accessed 6,536 times

during 2022. The MTN Tickborne Disease Data is available on Maine CDC’s website at www.maine.gov/idepi.

Please see Appendix 9 for a sample table and Appendix 10 for sample maps. Data can be broken down by:

• Town

• County

• Gender

• Age Group

Maine CDC Report to Maine Legislature on Lyme Disease - 2023

13

In 2018, Maine CDC also launched a Data Dashboard for tickborne diseases on the MTN. This data

dashboard is updated weekly with the rates (per 100,000) and number of cases of Lyme disease, anaplasmosis,

and babesiosis at both the state and county level. This is available as tables, charts, and maps. Case counts

include confirmed and probable cases and data updates occur bi-monthly as Maine CDC classifies new cases.

The data dashboard also includes a trend chart of suspected tick-related emergency department visits by week

and compares the counts to the previous year. The dashboard also includes suspected tick-related emergency

visits as a percent of all emergency visits, allowing for comparison with previous years. Maine CDC obtains

suspected tick-related emergency department visits from hospitals in Maine. This section of the portal received

1,968 visits in 2022. Please see Appendix 11 for a sample trend chart.

Maine CDC’s main prevention message is encouraging Maine residents and visitors to use personal protective

measures to prevent tick exposures. Personal protective measures include avoiding tick habitat, using EPA-

approved repellents, wearing long sleeves and pants, and daily tick checks and tick removal after being in tick

habitats (ticks must be attached >24 hours to transmit Lyme disease). Persons who spent time in tick habitats

should consult a medical provider if they have unexplained rashes, fever, or other unusual illnesses during the

first several months after exposure. Possible community approaches to prevent Lyme disease include landscape

management and control of deer herd populations.

Maine CDC partners with the University of Maine Cooperative Extension Office to monitor the identification

of deer ticks (Ixodes scapularis) in Maine through a passive submission system.

Beginning in April 2019, the University of Maine Cooperative Extension Office offers the testing of deer ticks

for the pathogens that cause Lyme disease, anaplasmosis, and babesiosis. In 2020, the Cooperative Extension

Office added a panel to test non-Ixodes tick species, including the American dog tick and lone star tick for the

pathogens that cause Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever, ehrlichiosis, and tularemia. In 2023, the Cooperative

Extension Office plans to add Powassan and Heartland virus testing to the Ixodes and non-Ixodes panels,

respectively. While the testing of ticks should not be used for clinical diagnosis or medical treatment decisions,

this service provides surveillance information on ticks and tickborne diseases in Maine. For more information

on this service, please visit www.ticks.umaine.edu. Data on the tick submission and tick testing results for 2022

can be found in Appendix 12.

6. A summary of laws of other states enacted during the past year related to the diagnosis, treatment, and

insurance coverage for Lyme disease and other tickborne illnesses based on resources made available

by federal Centers for Disease Control and Prevention or other organizations

Maine CDC performed a search of state and federal legislation. A state-by-state listing of legislation relating

to Lyme and other tickborne diseases can be found in Appendix 13.

Maine CDC Report to Maine Legislature on Lyme Disease - 2023

14

Appendix 1

Maine Lyme disease statistics

Number and Rate per 100,000 persons of Lyme Disease Cases by County of Residence – Maine, 2018-2022*

County

2018

Count

2018

Rate

2019

Count

2019

Rate

2020

Count

2020

Rate

2021

Count

2021

Rate

2022

Count*

2022

Rate*

Androscoggin

68

63.2

98

90.5

40

36.9

64

57.6

76

68.4

Aroostook

4

6.0

2

3.0

4

6.0

3

4.5

12

17.9

Cumberland

288

98.1

354

120.0

178

60.3

226

74.0

350

114.7

Franklin

13

43.5

39

129.1

18

59.6

24

80.8

40

2.9

Hancock

174

317.5

193

351.0

117

212.8

186

331.0

360

640.7

Kennebec

182

149.1

279

228.1

125

102.2

167

134.2

230

16.6

Knox

105

264.0

238

598.4

121

304.2

138

335.9

261

635.3

Lincoln

63

183.4

132

381.1

65

187.7

65

181.4

183

510.8

Oxford

48

83.3

88

151.8

43

74.2

57

97.2

63

107.5

Penobscot

78

51.6

111

73.0

85

55.9

126

82.5

238

17.2

Piscataquis

3

17.9

4

23.8

4

23.8

5

29.1

15

87.4

Sagadahoc

47

131.9

83

231.5

27

75.3

45

121.4

101

272.5

Somerset

45

88.9

68

134.7

37

73.3

80

158.1

125

247.1

Waldo

78

196.5

143

360.1

91

229.1

113

283.1

203

508.6

Washington

15

47.6

31

98.8

33

105.2

38

122.1

93

298.8

York

201

97.5

312

150.3

141

67.9

173

80.6

267

124.4

State

1412

105.0

2175

161.8

1118

84.0

1510

110.0

2617

188.9

*2022 data are preliminary as of 03/08/2023

Note about the data: Effective 01/02/2022, CSTE changed the Lyme disease surveillance case definition to a lab-only definition, which includes only probable cases.

All data prior to 2022 includes confirmed and probable cases. See section Ia for more information.

*2022 data are preliminary as of 03/08/2023

Note about the data: Effective 01/02/2022, CSTE changed the Lyme disease surveillance case definition to a lab-only definition, which includes only probable cases.

All data prior to 2022 includes confirmed and probable cases. See section Ia for more information.

1384

1412

1216

1498

1859

1412

2175

1129

1510

2617

0

300

600

900

1200

1500

1800

2100

2400

2700

3000

2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 2019 2020 2021 2022

Number of Cases

Lyme Disease Cases - Maine, 2013-2022*

Maine CDC Report to Maine Legislature on Lyme Disease - 2023

15

*2022 data are preliminary as of 03/08/2023

Note about the data: Effective 01/02/2022, CSTE changed the Lyme disease surveillance case definition to a lab-only definition, which includes only probable cases.

All data prior to 2022 includes confirmed and probable cases. See section Ia for more information.

*2022 data are preliminary as of 03/08/2023

Note about the data: Effective 01/02/2022, CSTE changed the Lyme disease surveillance case definition to a lab-only definition, which includes only probable cases.

All data prior to 2022 includes confirmed and probable cases. See section Ia for more information.

0.0

20.0

40.0

60.0

80.0

100.0

120.0

140.0

160.0

180.0

200.0

2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 2019 2020 2021 2022

Rate per 100,000

Lyme Disease Incidence - Maine, New England, and US, 2013-2022*

Maine US New England

0.0

50.0

100.0

150.0

200.0

250.0

300.0

350.0

400.0

2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 2019 2020 2021 2022

Rate per 100,000 persons

Lyme Disease Rates by Age Group, Maine 2013-2022*

<5 5-14 15-24 25-44 45-64 65+

Maine CDC Report to Maine Legislature on Lyme Disease - 2023

16

Appendix 2

Maine tickborne disease statistics (excluding Lyme disease)

Number of Selected Tickborne Disease Cases by County of Residence – Maine, 2022*

County

Anaplasmosis

Babesiosis

Ehrlichiosis

Ehrlichiosis/

Anaplasmosis

Undetermined

Hard Tick

Relapsing Fever

Powassan

Spotted Fever

Rickettsiosis

Androscoggin

54

11

1

0

2

0

0

Aroostook

1

0

0

0

0

0

0

Cumberland

88

25

0

0

1

1

0

Franklin

18

1

0

0

0

0

0

Hancock

78

23

0

0

2

0

0

Kennebec

87

24

4

1

2

0

0

Knox

94

28

1

0

1

0

0

Lincoln

108

19

1

0

1

0

1

Oxford

31

3

0

0

0

0

0

Penobscot

45

7

0

0

1

1

0

Piscataquis

1

0

0

0

0

0

0

Sagadahoc

38

9

0

0

1

0

0

Somerset

27

3

0

0

0

0

0

Waldo

86

19

0

0

0

1

0

Washington

16

3

0

0

0

0

0

York

52

17

0

0

1

1

0

Total

824

192

7

1

12

4

1

* 2022 data are preliminary as of 03/08/2023

Number of Selected Tickborne Disease Cases– Maine, 2013 - 2022*

2013

2014

2015

2016

2017

2018

2019

2020

2021

2022*

Anaplasmosis

94

191

185

372

663

476

685

443

841

824

Babesiosis

36

42

55

82

118

101

138

66

201

192

Ehrlichia chaffeensis

3

8

5

7

10

19

13

2

4

7

Ehr/Ana undetermined

2

6

1

4

10

9

2

2

0

1

Hard Tick Relapsing Fever

0

0

0

0

6

8

13

12

9

12

Powassan

1

0

1

1

3

0

2

1

3

4

SFR

2

3

1

4

3

10

5

0

2

1

* 2022 data are preliminary as of 03/08/2023

Maine CDC Report to Maine Legislature on Lyme Disease - 2023

17

* 2022 data are preliminary as of 03/08/2023

0

100

200

300

400

500

600

700

800

900

2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 2019 2020 2021 2022

Number of Cases

Anaplasmosis and Babesiosis, Maine 2013-2022*

Anaplasmosis Babesiosis

Maine CDC Report to Maine Legislature on Lyme Disease - 2023

18

Appendix 3

Peer-reviewed medical literature related to tickborne diseases – bibliography: 2022 Diagnostics and

Surveillance

• Bishop A, Borski J, Wang HH, Donaldson TG, Michalk A, Montgomery A, Heldman S, Mogg M,

Derouen Z, Grant WE, Teel PD. (2022). Increasing incidence of spotted fever group rickettsioses in

the United States, 2010-2018. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 22(9):491-497. doi:

10.1089/vbz.2022.0021.

• Blanchard L, Jones-Diette J, Lorenc T, Sutcliffe K, Sowden A, Thomas J. (2022). Comparison of

national surveillance systems for Lyme disease in humans in Europe and North America: A policy

review. BMC Public Health. 7; 22(1):1307. doi: 10.1186/s12889-022-13669-w.

• Bloch EM, Day JR, Krause PJ, Kjemtrup A, O'Brien SF, Tobian AAR, Goel R. (2022).

Epidemiology of hospitalized patients with babesiosis, United States, 2010-2016. Emerg Infect Dis.

28(2):354–62. doi: 10.3201/eid2802.210213.

• Burtis JC, Foster E, Schwartz AM, Kugeler KJ, Maes SE, Fleshman AC, Eisen RJ. (2022).

Predicting distributions of blacklegged ticks (Ixodes scapularis), Lyme disease spirochetes

(Borrelia burgdorferi sensu stricto) and human Lyme disease cases in the eastern United States.

Ticks Tick Borne Dis. 13(5):102000. doi: 10.1016/j.ttbdis.2022.102000.

• Fleshman AC, Foster E, Maes SE, Eisen RJ. (2022). Reported county-level distribution of seven

human pathogens detected in host-seeking Ixodes scapularis and Ixodes pacificus (Acari: Ixodidae)

in the contiguous United States. J Med Entomol. 59(4):1328-1335. doi: 10.1093/jme/tjac049.

• Giménez-Richarte Á, Ortiz de Salazar MI, Giménez-Richarte MP, Collado M, Fernández PL,

Clavijo C, Navarro L, Arbona C, Marco P, Ramos-Rincon JM. (2022). Transfusion-transmitted

arboviruses: Update and systematic review. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 16(10):e0010843. doi:

10.1371/journal.pntd.0010843.

• Goff NK, Dou T, Higgins S, Horn EJ, Morey R, McClellan K, Kurouski D, Rogovskyy AS. (2022).

Testing Raman spectroscopy as a diagnostic approach for Lyme disease patients. Front Cell Infect

Microbiol. 12:1006134. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2022.1006134.

• Häring J, Hassenstein MJ, Becker M, Ortmann J, Junker D, Karch A, Berger K, Tchitchagua T,

Leschnik O, Harries M, Gornyk D, Hernández P, Lange B, Castell S, Krause G, Dulovic A,

Strengert M, Schneiderhan-Marra N. (2022). Borrelia multiplex: a bead-based multiplex assay for

the simultaneous detection of Borrelia specific IgG/IgM class antibodies. BMC Infect Dis.

22(1):859. doi: 10.1186/s12879-022-07863-9.

• Hoeve-Bakker BJA, Jonker M, Brandenburg AH, den Reijer PM, Stelma FF, van Dam AP, van

Gorkom T, Kerkhof K, Thijsen SFT, Kremer K. (2022). The performance of nine commercial

serological screening assays for the diagnosis of Lyme borreliosis: a multicenter modified two-gate

design study. Microbiol Spectr. 10(2):e0051022. doi: 10.1128/spectrum.00510-22.

• Hunt KM, Michelson KA, Balamuth F, Thompson AD, Levas MN, Neville DN, Kharbanda A,

Maine CDC Report to Maine Legislature on Lyme Disease - 2023

19

Chapman L, Nigrovic LE; for Pedi Lyme Net. (2022). Racial differences in the diagnosis of Lyme

disease in children. Clin Infect Dis. ciac863. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciac863.

• Johnston D, Kelly JR, Ledizet M, Lavoie N, Smith RP, Parsonnet J, Schwab J, Stratidis J, Espich S,

Lee G, Maciejewski KR, Deng Y, Majam V, Zheng H, Bonkoungou SN, Stevens J, Kumar S,

Krause PJ. (2022). Frequency and geographic distribution of Borrelia miyamotoi, Borrelia

burgdorferi, and Babesia microti infections in New England residents. Clin Infect Dis. ciac107. doi:

10.1093/cid/ciac107.

• Karshima SN, Karshima MN, Ahmed MI. (2022). Global meta-analysis on Babesia infections in

human population: prevalence, distribution, and species diversity. Pathog Glob Health. 116(4):220-

235. doi: 10.1080/20477724.2021.1989185.

• Khan F, Allehebi Z, Shabi Y, Davis I, LeBlanc J, Lindsay R, Hatchette T. (2022). Modified two-

tiered testing enzyme immunoassay algorithm for serologic diagnosis of Lyme disease. Open

Forum Infect Dis. 9(7):ofac272. doi: 10.1093/ofid/ofac272.

• Kight E, Alfaro R, Gadila SKG, Chang S, Evans D, Embers M, Haselton F. (2022). Direct capture

and early detection of Lyme disease spirochete in skin with a microneedle patch. Biosensors

(Basel). 12(10):819. doi: 10.3390/bios12100819.

• Klingelhöfer D, Braun M, Brüggmann D, Groneberg DA. (2022). Ticks in medical and

parasitological research: Globally emerging risks require appropriate scientific awareness and

action. Travel Med Infect Dis. 50:102468. doi: 10.1016/j.tmaid.2022.102468.

• Kobayashi T, Auwaerter PG. (2022). Diagnostic testing for Lyme disease. Infect Dis Clin North

Am. 36(3):605-620. doi: 10.1016/j.idc.2022.04.001.

• Kobayashi T, Higgins Y, Melia MT, Auwaerter PG. (2022). Mistaken identity: Many diagnoses are

frequently misattributed to Lyme disease. Am J Med. 135(4):503-511.e5. doi:

10.1016/j.amjmed.2021.10.040.

• Kugeler KJ, Cervantes K, Brown CM, Horiuchi K, Schiffman E, Lind L, Barkley J, Broyhill J,

Murphy J, Crum D, Robinson S, Kwit NA, Mullins J, Sun J, Hinckley AF. (2022). Potential

quantitative effect of a laboratory-based approach to Lyme disease surveillance in high-incidence

states. Zoonoses Public Health. 69(5):451-457. doi: 10.1111/zph.12933.

• Kugeler KJ, Mead PS, Schwartz AM, Hinckley AF. (2022). Changing trends in age and sex

distributions of Lyme disease-United States, 1992-2016. Public Health Rep. (4):655-659. doi:

10.1177/00333549211026777.

• Lutaud R, Verger P, Peretti-Watel P, Eldin C. (2022). When the patient is making the (wrong?)

diagnosis: a biographical approach to patients consulting for presumed Lyme disease. Fam Pract.

cmac116. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cmac116.

• Ly DP. (2022). Black-white differences in the clinical manifestations and timing of initial Lyme

disease diagnoses. J Gen Intern Med. 37(10):2597-2600. doi: 10.1007/s11606-021-07129-1.

Maine CDC Report to Maine Legislature on Lyme Disease - 2023

20

• Mead P. (2022). Epidemiology of Lyme disease. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 36(3):495-521. doi:

10.1016/j.idc.2022.03.004.

• Pedersen RR, Kragh KN, Fritz BG, Ørbæk M, Østrup Jensen P, Lebech AM, Bjarnsholt T. (2022).

A novel Borrelia-specific real-time PCR assay is not suitable for diagnosing Lyme

neuroborreliosis. Ticks Tick Borne Dis. 13(5):101971. doi: 10.1016/j.ttbdis.2022.101971.

• Pelletier J, Guillot C, Rocheleau JP, Bouchard C, Baron G, Bédard C, Dibernardo A, Lindsay LR,

Leighton PA, Aenishaenslin C. (2022). The added value of One Health surveillance: data from

questing ticks can provide an early signal for anaplasmosis outbreaks in animals and humans. Can J

Public Health. doi: 10.17269/s41997-022-00723-8.

• Peniche-Lara G, Moo-Salazar I, Dzul-Rosado K. (2022). A Multiplex PCR assay for a differential

diagnostic of rickettsiosis, Lyme disease and scrub typhus. J Vector Borne Dis. 59(2):178-181. doi:

10.4103/0972-9062.337506.

• Pietikäinen A, Backman I, Henningsson AJ, Hytönen J. (2022). Clinical performance and

analytical accuracy of a C6 peptide-based point-of-care lateral flow immunoassay in Lyme

borreliosis serology. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 103(1):115657. doi:

10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2022.115657.

• Pietikäinen A, Glader O, Kortela E, Kanerva M, Oksi J, Hytönen J. (2022). Borrelia burgdorferi

specific serum and cerebrospinal fluid antibodies in Lyme neuroborreliosis. Diagn Microbiol Infect

Dis. 104(3):115782. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2022.115782.

• Pitrak D, Nguyen CT, Cifu AS. (2022). Diagnosis of Lyme disease. JAMA. 327(7):676-677. doi:

10.1001/jama.2022.0081.

• Pratt GW, Platt M, Velez A, Rao LV. (2022). A comparison of Lyme serological testing platforms

with a panel of clinically characterized samples from various stages of Lyme disease. J Appl Lab

Med. 7(6):1445-1449. doi: 10.1093/jalm/jfac047.

• Pratt GW, Platt M, Velez A, Rao LV. (2022). Utility of whole blood real-time PCR testing for the

diagnosis of early Lyme disease. Am J Clin Pathol. 158(3):327-330. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/aqac068.

• Rodino KG, Pritt BS. (2022). When to think about other Borreliae: Hard tick relapsing fever

(Borrelia miyamotoi), Borrelia mayonii, and beyond. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 36(3):689-701. doi:

10.1016/j.idc.2022.04.002.

• Rupani A, Elshabrawy HA, Bechelli J. (2022). Dermatological manifestations of tick-borne viral

infections found in the United States. Virol J. 19(1):199. doi: 10.1186/s12985-022-01924-w.

• Sabin AP, Scholze BP, Lovrich SD, Callister SM. (2022). Clinical evaluation of a Borrelia

modified two-tiered testing (MTTT) shows increased early sensitivity for Borrelia burgdorferi but

not other endemic Borrelia species in a high incidence region for Lyme disease in Wisconsin.

Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 105(1):115837. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2022.115837.

• Sanchez-Vicente S, Jain K, Tagliafierro T, Gokden A, Kapoor V, Guo C, Horn EJ, Lipkin WI,

Maine CDC Report to Maine Legislature on Lyme Disease - 2023

21

Tokarz R. (2022). Capture sequencing enables sensitive detection of tick-borne agents in human

blood. Front Microbiol. 13:837621. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2022.837621.

• Schotthoefer AM, Green CB, Dempsey G, Horn EJ. (2022). The spectrum of erythema migrans in

early Lyme disease: Can we improve its recognition? Cureus. 14(10):e30673. doi:

10.7759/cureus.30673.

• Sfeir MM, Meece JK, Theel ES, Granger D, Fritsche TR, Steere AC, Branda JA. (2022).

Multicenter clinical evaluation of modified two-tiered testing algorithms for Lyme disease using

Zeus scientific commercial assays. J Clin Microbiol. 60(5):e0252821. doi: 10.1128/jcm.02528-21.

• Stellrecht KA, Wilson LI, Castro AJ, Maceira VP. (2022). Automated real-time PCR detection of

tickborne diseases using the Panther Fusion open access system. Microbiol Spectr. 10(6):e0280822.

doi: 10.1128/spectrum.02808-22.

• Tetens MM, Dessau R, Ellermann-Eriksen S, Andersen NS, Jørgensen CS, Østergaard C, Bodilsen

J, Damgaard DF, Bangsborg J, Nielsen AC, Møller JK, Omland LH, Obel N, Lebech AM. (2022).

The diagnostic value of serum Borrelia burgdorferi antibodies and seroconversion after Lyme

neuroborreliosis, a nationwide observational study. Clin Microbiol Infect. 28(11):1500.e1-1500.e6.

doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2022.06.001.

• Theel ES. (2022). Molecular Testing for diagnosis of early Lyme disease. Am J Clin Pathol.

aqac080. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/aqac080.

• Tonnetti L, Dodd RY, Foster G, Stramer SL. (2022). Babesia blood testing: The first-year

experience. Transfusion. 62(1):135-142. doi: 10.1111/trf.16718.

• Trevisan G, Nan K, di Meo N, Bonin S. (2022). The impact of telemedicine in the diagnosis of

erythema migrans during the COVID pandemic: A Comparison with in-person diagnosis in the pre-

COVID era. Pathogens. 11(10):1122. doi: 10.3390/pathogens11101122.

• Vahey GM, Wilson N, McDonald E, Fitzpatrick K, Lehman J, Clark S, Lindell K, Pastula DM,

Perez S, Rhodes H, Gould CV, Staples JE, Cervantes K, Martin SW. (2022). Seroprevalence of

powassan virus infection in an area experiencing a cluster of disease cases: Sussex County, New

Jersey, 2019. Open Forum Infect Dis. 9(3):ofac023. doi: 10.1093/ofid/ofac023.

• Wojciechowska-Koszko I, Dziatlik J, Kwiatkowski P, Roszkowska P, Sienkiewicz M, Dołęgowska

B. (2022). Could the Optiplex Borrelia assay replace the traditional, two-step method of

diagnosing Lyme disease? Ann Agric Environ Med. 29(1):63-71. doi: 10.26444/aaem/147277.

• Wojciechowska-Koszko I, Kwiatkowski P, Sienkiewicz M, Kowalczyk M, Kowalczyk E,

Dołęgowska B. (2022). Cross-reactive results in serological tests for borreliosis in patients with

active viral infections. Pathogens. 11(2):203. doi: 10.3390/pathogens11020203.

• Wormser GP. (2022). A brief history of OspA vaccines including their impact on diagnostic testing

for Lyme disease. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 102(1):115572. doi:

10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2021.115572..

Maine CDC Report to Maine Legislature on Lyme Disease - 2023

22

Management and Treatment

• Akoolo L, Djokic V, Rocha SC, Ulloa L, Parveen N. (2022). Sciatic-vagal nerve stimulation by

electroacupuncture alleviates inflammatory arthritis in Lyme disease-susceptible C3H mice. Front

Immunol. 13:930287. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2022.930287.

• Allehebi ZO, Khan FM, Robbins M, Simms E, Xiang R, Shawwa A, Lindsay LR, Dibernardo A,

d'Entremont C, Crowell A, LeBlanc JJ, Haldane DJ. (2022). Lyme disease, anaplasmosis, and

babesiosis, Atlantic Canada. Emerg Infect Dis. 28(6):1292-1294. doi: 10.3201/eid2806.220443.

• Andreassen S, Lindland EMS, Beyer MK, Solheim AM, Ljøstad U, Mygland Å, Lorentzen ÅR, Reiso

H, Bjuland KJ, Pripp AH, Harbo HF, Løhaugen GCC, Eikeland R. (2022). Assessment of cognitive

function, structural brain changes and fatigue 6 months after treatment of neuroborreliosis. J Neurol.

doi: 10.1007/s00415-022-11463-7.

• Andreassen S, Solheim AM, Ljøstad U, Mygland Å, Lorentzen ÅR, Reiso H, Beyer MK, Harbo HF,

Løhaugen GCC, Eikeland R. (2022). Cognitive function in patients with neuroborreliosis: A

prospective cohort study from the acute phase to 12 months post treatment. Brain Behav. 12(6):e2608.

doi: 10.1002/brb3.2608.

• Apostolou P, Iliopoulos A, Beis G, Papasotiriou I. (2022). Supportive oligonucleotide therapy (SOT) as

a potential treatment for viral infections and Lyme disease: Preliminary results. Infect Dis Rep.

14(6):824-836. doi: 10.3390/idr14060084.

• Arnason S, Skogman BH. (2022). Effectiveness of antibiotic treatment in children with Lyme

neuroborreliosis - a retrospective study. BMC Pediatr. 22(1):332. doi: 10.1186/s12887-022-03335-w.

• Arvikar SL, Steere AC. (2022). Lyme Arthritis. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 36(3):563-577. doi:

10.1016/j.idc.2022.03.006.

• Aucott JN, Yang T, Yoon I, Powell D, Geller SA, Rebman AW. (2022). Risk of post-treatment Lyme

disease in patients with ideally-treated early Lyme disease: A prospective cohort study. Int J Infect Dis.

116:230-237. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2022.01.033.

• Baarsma ME, Claassen SA, van der Horst HE, Hovius JW, Sanders JM. (2022). Knowing the entire

story - a focus group study on patient experiences with chronic Lyme-associated symptoms (chronic

Lyme disease). BMC Prim Care. 23(1):139. doi: 10.1186/s12875-022-01736-5.

• Binder AM, Cherry-Brown D, Biggerstaff BJ, Jones ES, Amelio CL, Beard CB, Petersen LR, Kersh GJ,

Commins SP, Armstrong PA. (2022). Clinical and laboratory features of patients diagnosed with alpha-

gal syndrome-2010-2019. Allergy. doi: 10.1111/all.15539.

• Bloch EM, Zhu X, Krause PJ, Patel EU, Grabowski MK, Goel R, Auwaerter PG, Tobian AAR. (2022).

Comparing the epidemiology and health burden of Lyme disease and babesiosis hospitalizations in the

United States. Open Forum Infect Dis. 9(11):ofac597. doi: 10.1093/ofid/ofac597.

• Boyer PH, Lenormand C, Jaulhac B, Talagrand-Reboul E. (2022). Human co-infections

between Borrelia burgdorferi s.l. and other Ixodes-borne microorganisms: A systematic review.

Maine CDC Report to Maine Legislature on Lyme Disease - 2023

23

Pathogens. 11(3):282. doi: 10.3390/pathogens11030282.

• Brummitt SI, Harvey DJ, Smith WA, Barker CM, Kjemtrup AM. (2022). Assessment of physician

knowledge, attitudes, and practice for Lyme disease in a low-incidence state. J Med Entomol. Sep

20:tjac137. doi: 10.1093/jme/tjac137.

• Cabello FC, Embers ME, Newman SA, Godfrey HP. (2022). Borreliella burgdorferi antimicrobial-

tolerant persistence in Lyme disease and posttreatment Lyme disease syndromes. mBio. 13(3):e0344021.

doi: 10.1128/mbio.03440-21.

• Carson AS, Gardner A, Iweala OI. (2022). Where's the beef? Understanding allergic responses to red

meat in alpha-gal syndrome. J Immunol. 208(2):267-277. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.2100712.

• Crissinger T, Baldwin K. (2022). Early disseminated Lyme disease: Cranial neuropathy, meningitis,

and polyradiculopathy. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 36(3):541-551. doi: 10.1016/j.idc.2022.02.006.

• Dejace J. (2022). The role of the infectious disease consultation in Lyme disease. Infect Dis Clin North

Am. 36(3):703-718. doi: 10.1016/j.idc.2022.04.003.

• Delaney SL, Murray LA, Fallon BA. (2022). Neuropsychiatric symptoms and tick-borne diseases. Curr

Top Behav Neurosci. doi: 10.1007/7854_2022_406.

• Donta ST. (2022). What we know and don't know about Lyme disease. Front Public Health. 9:819541.

doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2021.819541.

• Drexler NA, Close R, Yaglom HD, Traeger M, Parker K, Venkat H, Villarroel L, Brislan J, Pastula DM,

Armstrong PA. (2022). Morbidity and functional outcomes following rocky mountain spotted fever

hospitalization-Arizona, 2002-2017. Open Forum Infect Dis. 9(10):ofac506. doi: 10.1093/ofid/ofac506.

• Dumic I, Jevtic D, Veselinovic M, Nordstrom CW, Jovanovic M, Mogulla V, Veselinovic EM, Hudson

A, Simeunovic G, Petcu E, Ramanan P. (2022). Human granulocytic anaplasmosis-a systematic review

of published cases. Microorganisms. 10(7):1433. doi: 10.3390/microorganisms10071433.

• Garro AC, Thompson AD, Neville DN, Balamuth F, Levas MN, Kharbanda AB, Bennett JE, Grant DS,

Aresco RK, Nigrovic LE; Pedi Lyme Net Network. (2022). Empiric antibiotics for children with

suspected Lyme disease. Ticks Tick Borne Dis. 13(5):101989. doi: 10.1016/j.ttbdis.2022.101989.

• Geebelen L, Lernout T, Devleesschauwer B, Kabamba-Mukadi B, Saegeman V, Belkhir L, De Munter

P, Dubois B, Westhovens R; Humtick Hospital Group, Van Oyen H, Speybroeck N, Tersago K. (2022).

Non-specific symptoms and post-treatment Lyme disease syndrome in patients with Lyme borreliosis: a

prospective cohort study in Belgium (2016-2020). BMC Infect Dis. 22(1):756. doi: 10.1186/s12879-022-

07686-8.

• Halperin JJ, Eikeland R, Branda JA, Dersch R. (2022). Lyme neuroborreliosis: known knowns, known

unknowns. Brain. 145(8):2635-2647. doi: 10.1093/brain/awac206.

• Halperin JJ. (2022). Nervous system Lyme disease-facts and fallacies. Infect Dis Clin North Am.

36(3):579-592. doi: 10.1016/j.idc.2022.02.007.

Maine CDC Report to Maine Legislature on Lyme Disease - 2023

24

• Hill EM, Frost A. (2022). Illness perceptions, coping, and health-related quality of life among

individuals experiencing chronic Lyme disease. Chronic Illn. 18(2):426-438. doi:

10.1177/1742395320983875.

• Hoornstra D, Azagi T, van Eck JA, Wagemakers A, Koetsveld J, Spijker R, Platonov AE, Sprong H,

Hovius JW. (2022). Prevalence and clinical manifestation of Borrelia miyamotoi in Ixodes ticks and

humans in the northern hemisphere: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Microbe.

3(10):e772-e786. doi: 10.1016/S2666-5247(22)00157-4.

• Johnson LB, Maloney EL. (2022). Access to care in Lyme disease: Clinician barriers to providing care.

Healthcare (Basel). 10(10):1882. doi: 10.3390/healthcare10101882.

• Kortela E, Kanerva MJ, Kurkela S, Oksi J, Koivisto M, Järvinen A. (2022). Consumption of healthcare

services and antibiotics in patients with presumed disseminated Lyme borreliosis before and after

evaluation of an infectious disease specialist. Ticks Tick Borne Dis. 13(1):101854. doi:

10.1016/j.ttbdis.2021.101854.

• Leavey K, MacKenzie RK, Faber S, Lloyd VK, Mao C, Wills MKB, Boucoiran I, Cates EC, Omar A,

Marquez O, Darling EK. (2022). Lyme borreliosis in pregnancy and associations with parent and

offspring health outcomes: An international cross-sectional survey. Front Med (Lausanne). 9:1022766.

doi: 10.3389/fmed.2022.1022766.

• Lyons TW, Kharbanda AB, Thompson AD, Bennett JE, Balamuth F, Levas MN, Neville DN, Lewander

DP, Bretscher BS, Kellogg MD, Nigrovic LE; Pedi Lyme Net. (2022). A clinical prediction rule for

bacterial musculoskeletal infections in children with monoarthritis in Lyme endemic regions. Ann

Emerg Med. 80(3):225-234. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2022.04.009.

• MacQueen D, Centellas F. (2022). Human granulocytic anaplasmosis. Infect Dis Clin North Am.

36(3):639-654. doi: 10.1016/j.idc.2022.02.008.

• Markowicz M, Kundi M, Stanek G, Stockinger H. (2022). Nonspecific symptoms following infection

with Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato: A retrospective cohort study. Ticks Tick Borne Dis. 13(1):101851.

doi: 10.1016/j.ttbdis.2021.101851.

• Marques A, Okpali G, Liepshutz K, Ortega-Villa AM. (2022). Characteristics and outcome of facial

nerve palsy from Lyme neuroborreliosis in the United States. Ann Clin Transl Neurol. 9(1):41-49. doi:

10.1002/acn3.51488.

• Marques A. (2022). Persistent symptoms after treatment of Lyme disease. Infect Dis Clin North Am.

36(3):621-638. doi: 10.1016/j.idc.2022.04.004.

• Marvel CL, Alm KH, Bhattacharya D, Rebman AW, Bakker A, Morgan OP, Creighton JA, Kozero EA,

Venkatesan A, Nadkarni PA, Aucott JN. (2022). A multimodal neuroimaging study of brain

abnormalities and clinical correlates in post treatment Lyme disease. PLoS One. 17(10):e0271425. doi:

10.1371/journal.pone.0271425.

Maine CDC Report to Maine Legislature on Lyme Disease - 2023

25

• Maxwell SP, Brooks C, McNeely CL, Thomas KC. (2022). Neurological pain, psychological

symptoms, and diagnostic struggles among patients with tick-borne diseases. Healthcare (Basel).

10(7):1178. doi: 10.3390/healthcare10071178. P

• McCarthy CA, Helis JA, Daikh BE. (2022). Lyme disease in children. Infect Dis Clin North Am.

36(3):593-603. doi: 10.1016/j.idc.2022.03.002.

• Meissner HC, Steere AC. (2022). Management of pediatric Lyme disease: updates from 2020 Lyme

guidelines. Pediatrics. 149(3):e2021054980. doi: 10.1542/peds.2021-054980.

• Montero E, Gray J, Lobo CA, González LM. (2022). Babesia and human babesiosis. Pathogens.

11(4):399. doi: 10.3390/pathogens11040399.

• Murray L, Alexander C, Bennett C, Kuvaldina M, Khalsa G, Fallon B. (2022). Kundalini yoga for post-

treatment Lyme disease: A preliminary randomized study. Healthcare (Basel). (7):1314. doi:

10.3390/healthcare10071314.

• Mustafiz F, Moeller J, Kuvaldina M, Bennett C, Fallon BA. (2022). Persistent symptoms, Lyme

disease, and prior trauma. J Nerv Ment Dis. 210(5):359-364. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0000000000001452.

• Nguyen CT, Cifu AS, Pitrak D. (2022). Prevention and treatment of Lyme disease. JAMA. 327(8):772-

773. doi: 10.1001/jama.2021.25302.

• Piantadosi A, Solomon IH. (2022). Powassan virus encephalitis. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 36(3):671-

688. doi: 10.1016/j.idc.2022.03.003.

• Radesich C, Del Mestre E, Medo K, Vitrella G, Manca P, Chiatto M, Castrichini M, Sinagra G. (2022).

Lyme Carditis: From pathophysiology to clinical management. Pathogens. 11(5):582. doi:

10.3390/pathogens11050582.

• Shen RV, McCarthy CA. (2022). Cardiac manifestations of Lyme disease. Infect Dis Clin North Am.

36(3):553-561. doi: 10.1016/j.idc.2022.03.001.

• Slomski A. (2022). Shorter duration of antibiotics noninferior for Lyme disease. JAMA. 328(20):2004.

doi: 10.1001/jama.2022.21305.

• Spichler-Moffarah A, Ong E, O'Bryan J, Krause PJ. (2022). Cardiac complications of human

babesiosis. Clin Infect Dis. ciac525. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciac525.

• Strle F, Wormser GP. (2022). Early Lyme disease (erythema migrans) and its mimics (southern tick-

associated rash illness and tick-associated rash illness). Infect Dis Clin North Am. 36(3):523-539. doi:

10.1016/j.idc.2022.03.005.

• Tuvshintulga B, Sivakumar T, Nugraha AB, Ahedor B, Batmagnai E, Otgonsuren D, Liu M, Xuan X,

Igarashi I, Yokoyama N. (2022). Combination of clofazimine and atovaquone as a potent therapeutic