Re-Crafting Games:

The Inner Life of Minecraft Modding

Nicholas Watson

A Thesis

In the Department

of

Communication Studies

Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements

For the Degree of

Doctor of Philosophy (Communication) at

Concordia University

Montréal, Québec, Canada

May 2019

© Nicholas Watson, 2019

CONCORDIA UNIVERSITY

SCHOOL OF GRADUATE STUDIES

This is to certify that the thesis prepared

By: Nicholas Watson

Entitled: Re-Crafting Games: The inner life of Minecraft modding

and submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of

DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY (Communication)

complies with the regulations of the University and meets the accepted standards with

respect to originality and quality.

Signed by the final examining committee:

Dr. Martin Lefebvre

Chair

Dr. David Nieborg

External Examiner

Dr. Darren Wershler

External to Program

Dr. Charles Acland

Examiner

Dr. Owen Chapman

Examiner

Dr. Mia Consalvo

Thesis Supervisor

Approved by

Dr. Jeremy Stolow, Graduate Program Director

June 20, 2019

Dr. André Roy

Dean, Faculty of Arts and Sciences

iii

ABSTRACT

Re-Crafting Games: The inner life of Minecraft Modding

Nicholas Watson, Ph.D.

Concordia University, 2019

Prior scholarship on game modding has tended to focus on the relationship between

commercial developers and modders, while the preponderance of existing work on the open-world

sandbox game Minecraft has tended to focus on children’s play or the program’s utility as an

educational platform. Based on participant observation, interviews with modders, discourse

analysis, and the techniques of software studies, this research uncovers the inner life of Minecraft

modding practices, and how they have become central to the way the game is articulated as a

cultural artifact. While the creative activities of audiences have previously been described in terms

of de Certeau’s concept of “tactics,” this paper argues that modders are also engaged in the

development of new strategies. Modders thus become “settlers,” forging a new identity for the

game property as they expand the possibilities for play. Emerging modder strategies link to the

ways that the underlying game software structures computation, and are closely tied to notions of

modularity, interoperability, and programming “best practices.” Modders also mobilize tactics and

strategies in the discursive contestation and co-regulation of gameplay meanings and programming

practices, which become more central to an understanding of game modding than the developer-

modder relationship. This discourse, which structures the circulation of gaming capital within the

community, embodies both monologic and dialogic modes, with websites, forum posts, chatroom

conversations, and even software artifacts themselves taking on persuasive inflections.

iv

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work is dedicated to Seanna and Steve Watson, for their unwavering support over the

years that it took to complete.

I wish to extend my heartfelt thanks to my thesis supervisor, Dr. Mia Consalvo, and to Drs.

Bart Simon and Darren Wershler, for advice, guidance, and support; and also to the rest of my

examination committee, including Drs. Charles Acland, Owen Chapman, and David Nieborg; and

to Drs. Maude Bonenfant, Jeremy Stolow, and William Buxton, who offered feedback on early

portions of this project.

Thank you also to advisers and mentors of my undergraduate and Master’s programs, who

helped to set me on the path that led here: Drs. John Haslem, Larry Breitborde, Celia Pearce, and

Amy Bruckman.

I am especially grateful to all those in the Minecraft modding community who made this

work possible. Some of these people were interviewees and participants in my ethnographic

research; others did not participate directly, but provided advice, technical assistance, and guidance

on what I should explore and whom I should talk to. In alphabetical order: Alta, asie, capitalthree,

card1null, Cervator, copygirl, Icoso, JAvery, LShen, Mezz, modmuss50, Nikky, Omira, Qwil,

SarahK, ScriveShark, Tothor, Velo, VicNightfall, XCompWiz, Zoll, and several anonymous helpers

and participants.

Finally, thank you to Jason Wakeland, Laura Lewellen, Trish Audette, Ryan Scheiding,

Victoria Puusa, and Tugger the Siamese cat, for moral support.

Funding for portions of this research and related projects was provided by the mLab at

Concordia University; the Technoculture, Art, & Games research centre (Concordia University); the

Milieux Institute for Arts, Culture, and Technology (Concordia University); and a SSHRC-D award

grant from the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada.

v

TABLE OF CONTENTS

LIST OF FIGURES ........................................................................ IX

I. INTRODUCTION ........................................................................ 1

1.1 Mod, break, win! ................................................................................ 1

1.2 Background on Minecraft ...................................................................... 4

1.3 Variants and lineages of Minecraft .......................................................... 6

1.3.1 Java Edition ........................................................................................................................ 6

1.3.2 Pocket and Bedrock editions .................................................................................................. 7

1.3.3 Legacy console editions ......................................................................................................... 8

1.3.4 MinecraftEdu and Minecraft: Education Edition .................................................................... 8

1.4 Beginning to define "mods" .................................................................. 11

1.5 Modding frameworks .......................................................................... 16

1.6 Blueprint .......................................................................................... 18

1.6.1 Purpose and scope .............................................................................................................. 18

1.6.2 About this document ........................................................................................................... 18

II. REVIEW AND COMMENTARY ON THE LITERATURE ............................ 22

2.1 Under the influence: Mass media and audience passivity.............................. 22

2.1.1 The spectre of effects studies ................................................................................................. 22

2.2 Voices from the listeners ...................................................................... 25

2.2.1 Wandering lines: How videogames invite participatory action ................................................ 28

2.3 Commercial media meet the digital commons ........................................... 31

2.3.1 Making, hacking, remixing ................................................................................................. 33

2.3.2 Converging on co-creation ................................................................................................... 35

2.3.3 Enclosure of the digital commons ......................................................................................... 37

2.4 So… which of these things qualifies as modding? ....................................... 41

2.4.1 Why mod anyway? ............................................................................................................ 44

2.5 Research on Minecraft ........................................................................ 46

2.5.1 A tool for teachers ............................................................................................................... 46

2.5.2 Minecraft in children’s social and psychological development .................................................. 48

2.5.3 Minecraft in play ................................................................................................................ 48

2.5.4 Produsage, platform rhetoric, and Minecraft exceptionalism ................................................... 51

2.6 What’s missing .................................................................................. 53

III. A WORKBENCH OF THEORY AND METHOD .................................... 55

3.1 Rationale ......................................................................................... 55

3.2 Research questions ............................................................................. 55

3.3 Key themes ....................................................................................... 56

3.3.1 Tactics and strategies, poaching and settling ......................................................................... 56

3.3.2 Rationalization and operational logics ................................................................................. 57

3.3.3 Modder discourse and gaming capital ................................................................................... 58

vi

3.4 Other theoretical tools ........................................................................ 60

3.4.1 Productive play .................................................................................................................. 60

3.4.2 Remix and hacker culture ................................................................................................... 60

3.5 Methodological orientation .................................................................. 62

3.6 Methodological tools and activities ........................................................ 64

3.6.1 Ethnography in online contexts ............................................................................................ 64

3.6.2 Interviews with modders ..................................................................................................... 70

3.6.3 Discourse analysis and dual reading..................................................................................... 71

3.6.4 Approaches from software and platform studies ..................................................................... 75

3.7 The expedition begins ......................................................................... 77

IV. SETTLING MINECRAFT ............................................................ 78

4.1 Game Modes: A non-linear proliferation of Minecrafts ............................... 79

4.1.2 Rules and partitions: From implicit to hard-coded ................................................................. 80

4.1.3 The tactics that helped define game mode.............................................................................. 81

4.2 The strategies and tactics of emergent play ............................................... 89

4.2.1 Strategic design vs. tactical modding .................................................................................... 91

4.2.2 Tactics reconfigure strategies ................................................................................................ 98

4.2.3 Commercial developer tactics? .............................................................................................. 99

4.2.4 Modders develop strategies of their own .............................................................................. 104

4.3 The platform: Heartland and frontier .................................................... 105

4.3.1 Vanilla gameplay and the settlement of the frontier.............................................................. 107

4.3.2 Platforms, possibilities, and pioneer rhetoric ........................................................................ 108

4.3.3 “A huge melting pot of emergent gameplay” ....................................................................... 110

V. BETTER THAN MINECAMP: AN UNCONVENTIONAL CONVENTION ........ 113

5.1 Preparing for the convention: Adventures in building and chaos .................. 114

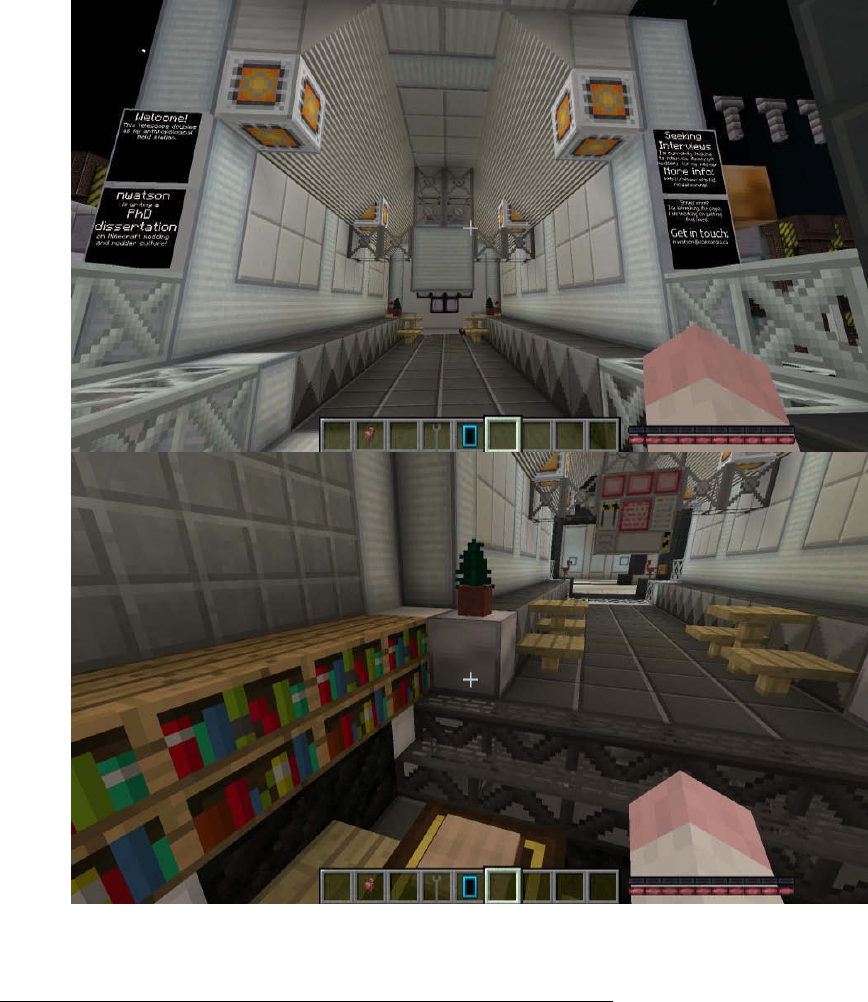

5.2 Spatial organization and logistics in “SPAAAAAAAAACCCEE!” ............. 125

5.2.1 Industrial Hub ................................................................................................................. 126

5.2.2 Magical District ............................................................................................................... 127

5.2.3 Nature Dome ................................................................................................................... 128

5.2.4 OpenComputers ............................................................................................................... 128

5.2.5 The Fun Zone .................................................................................................................. 130

5.2.6 Centrepieces ..................................................................................................................... 131

5.2.7 The Panel Room .............................................................................................................. 134

5.2.8 Transportation and orienteering ........................................................................................ 137

5.2.9 My field station ................................................................................................................ 141

5.3 “Minecraft’s got problems”: The keynote presentation ............................. 142

5.3.1 The keynote address finally begins...................................................................................... 145

5.4 Minecamp Earth: The meme/cringe generator ........................................ 148

5.5 Curiosity and chaos: crashing and exploding all the things ......................... 150

5.5.1 Ending BTM ................................................................................................................... 151

5.6 The lessons of BTM Moon ................................................................. 160

VI. OPERATIONAL LOGICS AND THE RATIONALIZATION OF MODDING ..... 163

vii

6.1 Domains of rationalization ................................................................. 163

6.2 Exposing operational logics across domains ............................................ 164

6.3 Operational logic families .................................................................. 166

6.3.1 Logic families in summary ................................................................................................ 166

6.3.2 Chunk-based geography .................................................................................................... 167

6.3.3 Block-based metaphysics ................................................................................................... 174

6.4 Other operational logics of computation and practice ................................ 184

6.4.1 Forge infrastructure: events, coremods, and public utilities .................................................... 184

6.4.2 Source code: using the right tools ........................................................................................ 189

6.5 Counterpoint: tactical modding is alive and well ..................................... 190

VII. MODDING DISCOURSES ........................................................ 192

7.1 Venues of discourse .......................................................................... 194

7.1.1 Asynchronous message boards ........................................................................................... 194

7.1.2 Real-time chat .................................................................................................................. 202

7.1.3 Wikis .............................................................................................................................. 204

7.1.4 CurseForge ...................................................................................................................... 208

7.1.5 Other venues and honourable mentions .............................................................................. 210

7.1.6 Usage patterns ................................................................................................................. 212

7.2 Software infrastructure as discourse...................................................... 213

7.3 Dissemination and co-regulation of modder expertise ............................... 215

7.4 Ownership, authorship, and authority ................................................... 220

7.4.1 Two types of incompatibility ............................................................................................. 222

7.4.2 Better Than Wolves and “intentional” incompatibility ........................................................ 223

7.4.3 Terms of play ................................................................................................................... 225

7.4.4 Control and concealment ................................................................................................... 228

7.5 Modding discourses in retrospect ......................................................... 229

7.6 Coda: Some final thoughts on gaming capital .......................................... 230

VIII. CONCLUSION .................................................................... 232

8.1 Other worlds of modding ................................................................... 232

8.2 Strategy, fantasy, and the promise of the platform .................................... 234

8.3 Whose game is it anyway? .................................................................. 237

8.4 Co-productive oscillations: power, rhetoric, and capital in the re-crafting of

games ................................................................................................ 238

APPENDIX A. A VERY BRIEF SUMMARY OF OBJECT-ORIENTED

PROGRAMMING CONCEPTS IN JAVA ........................................... 243

APPENDIX B. CUSTOM BLOCK MOD CODE ....................................... 247

File: ModBasic.java .............................................................................. 247

File: BlockNifty.java ............................................................................. 248

Info: Common and client proxies .............................................................. 249

File: CommonProxy.java ........................................................................ 250

viii

File: ClientProxy.java ............................................................................ 250

Resource files....................................................................................... 251

APPENDIX C. FORGE HOOKS: REGISTRIES AND EVENTS ....................... 253

GLOSSARY .............................................................................. 257

BIBLIOGRAPHY ......................................................................... 265

OTHER REFERENCES .................................................................. 276

ix

LIST OF FIGURES

Figure 1-1. Minecraft gameplay screenshots .................................................................................. 4

Figure 1-2. The crafting interface .................................................................................................. 5

Figure 1-3. Timeline: 10 years of Minecraft development ............................................................. 10

Figure 1-4. Minecraft gameplay screenshots, featuring mods ........................................................ 14

Figure 3-1. List of guiding questions for participant interviews ..................................................... 71

Figure 3-2. Counts of captured threads from Minecraft-related web forums ................................... 74

Figure 4-1. The ground rules for Enigma Island and Monarch of Madness ......................................... 84

Figure 4-2. Enigma Island rules enforcement ................................................................................. 85

Figure 4-3. “Flip this lever when you have killed all the zombies” ................................................ 86

Figure 4-4. Accept Your Own Adventure instructional signs .............................................................. 89

Figure 4-5. Java software deployment chain ................................................................................ 92

Figure 4-6. Jar modding and jar injection .................................................................................... 95

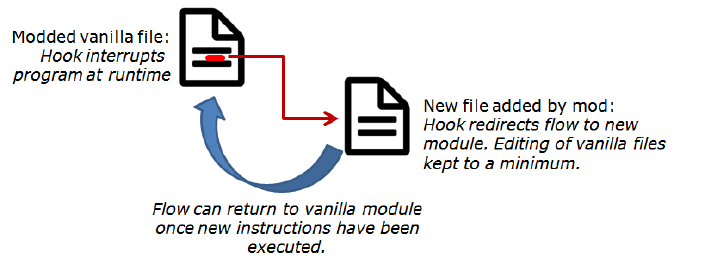

Figure 4-7. Code hooks............................................................................................................... 97

Figure 4-8. Software platform and possibility space .................................................................... 109

Figure 4-9. Modders are frontier settlers .................................................................................... 109

Figure 5-1. A view of part of the unfinished space station ........................................................... 115

Figure 5-2. BTM demo booth ................................................................................................... 115

Figure 5-3. The Spathi Discriminator, my initial on-site ethnographic field station ...................... 118

Figure 5-4. DJ Flamin’ GO ....................................................................................................... 119

Figure 5-5. WorldEdit copy/paste operations at BTM ................................................................ 120

Figure 5-6. “Wait and drink a tea ^^ ” ....................................................................................... 121

Figure 5-7. Original and modified telescope exteriors ................................................................. 122

Figure 5-8. The BTM demo booth for the gadget mod Turret Mod Rebirth .................................... 127

Figure 5-9. Amadornes plays an OpenComputers-based Tetris-clone on his stream ...................... 129

Figure 5-10. The Fun Zone demo booth for copygirl's WearableBackpacks .................................... 130

Figure 5-11. The BTM crash/bug-counter screen on Day 2 ........................................................ 132

Figure 5-12. The panel room ..................................................................................................... 135

Figure 5-13. Map of BTM Moon station .................................................................................... 140

Figure 5-14. Views of the space telescope field station ................................................................ 142

Figure 5-15. End-of-convention lunar dance party ...................................................................... 155

Figure 5-16. Carminite reactor detonations take their toll on the spawn plaza ............................. 157

Figure 5-17. Effects of the chaos crystal detonation .................................................................... 159

Figure 6-1. Diagram of a portion of a Minecraft world ............................................................... 168

Figure 6-2. Chunk boundary visualization in Minecraft 1.13 ...................................................... 172

Figure 6-3. Viewing chunk data for a Minecraft world using NBTExplorer 2.8.0 ......................... 173

Figure 6-4. The relationship between blocks and items ............................................................... 175

Figure 6-5. An illustration of the data relationships pertaining to the Block class ......................... 177

Figure 7-1. Screenshot of the #modder-support channel on Minecraft Forge Discord .................. 204

Figure 7-2. Example of a CurseForge project page ..................................................................... 209

Figure C-1. The Forge event model in action ............................................................................. 255

1

I. INTRODUCTION

1.1 Mod, break, win!

I won Minecraft while sitting at my dining-room table in August 2014.

Those familiar with the open-ended nature of Mojang AB’s open-ended, block-building

sandbox game may consider this an absurd statement, and they may have a point. How can you

“win” a game that, by design, lacks end-goals and victory conditions? Some might say that

Minecraft’s win condition constitutes travelling to a realm named The End, defeating the fearsome

Ender Dragon, and sitting through the 10-minute text scroll of the “End Poem”—a sort of

philosophical reflection that is beloved by some, derided by others (Chatfield, 2012). But the truth

about The End quest, which was added during the game’s transition from Beta to the Official (and

supposedly “Finished”) Released in 2011, is that it ended nothing. For the player, it is little more

than a detour: unlike the villains of traditional epics, the dragon’s presence is not felt in gameplay

prior to its defeat, so its subsequent absence changes little, and the day-to-day dramas of Minecraft

life unfold much as they had before. Little changed for the game’s developers too, despite The End

having been the exclamation mark on the game’s official release announcement. Markus “Notch”

Persson, the original creator, passed the torch to other developers, who have continued to radically

transform the game with incremental updates and new features in the years since.

In any case, that’s not what I mean by winning.

I won Minecraft by finding a sneaky solution to the ever-present tension of its Survival Mode

gameplay: the problem of resource scarcity. True, a procedurally-generated Minecraft world

technically has an inexhaustible supply of food, energy, building materials, and precious minerals,

but then so does our real universe—most of it is just very hard to get to. Time, labour, and

considerable risk to life and limb is involved in extracting the infinite-yet-sparsely-distributed

resource wealth of a Minecraft world. Diamonds, the most coveted material, are found only in the

deepest layers of the Earth, scattered between treacherous lava-pools and deadly monsters. Over

2

time, one’s Minecraft gameplay evolves from mere survival and subsistence to enrichment,

expansion of wealth, and expansion of the means to acquire yet more wealth; but scarcity and

friction are always present in some form. Popular technology and magic mods—themed, fan-made

changes and additions to the game—preserve this dynamic, even as they add modes of automation

and optimization that further expand the player’s ability to accrue valuable resources: the new

machines and arcane devices require increasing amounts of rare material to function. Even the most

successful Minecraft industrialist/wizard still considers diamond a rare and precious commodity.

But not me. I found a way to make as many diamonds as I could ever want, and then some.

I found a way to transmute common trash into treasure. I discovered the Minecraft equivalent of the

Philosopher’s Stone.

I am certainly not the first person to have done something like this, but I was the first on this

particular server—operated by a colleague and populated by students and professors at our

institution—and with this particular curated set of mods and game rules, or modpack. While

experimenting with the design of automated machinery, I discovered a curious interaction between a

well-known technology mod and an equally popular magic mod that were probably never intended

to be used together. By letting a robotic arm wield a magic wand, I could build a factory that

perpetually transformed blocks of cobblestone (one of the few truly infinitely-generable resources)

into diamonds, gold, or anything else I wanted.

1

Of course I was cheating, but in a manner that I had arrived at through play, one that

respected the non-negotiable rules of code—what games scholars Salen and Zimmerman (2003)

would call the “constituative rules” (sic.)—if not the design (operational rules) and spirit (implicit

rules) of the game. As an assistant to the server operator, I could also have used administrator

commands to give myself diamonds at any time, but to do so would have been to step outside the

1

The wand is normally used to rapidly exchange large numbers of blocks in a player’s inventory (e.g. diamond

blocks) with blocks on the ground (e.g. cobblestone). It is supposed to remove said blocks from the player’s

inventory when they are “spent,” but because of the way the two different mods were programmed, this failed

to happen when the robotic arm was holding the wand.

3

player role; as an option that had been available all along, rather than one cleverly derived from play

itself, this would hardly make for an interesting form of “winning.”

There was a player on our server—let’s call him ‘HT’—who had achieved a sort of demi-god

status. Through many hours of gameplay, he had pursued every mod’s tech tree to its conclusion,

built every kind of machine, crafted every kind of equipment, defeated every kind of monster, and

collected some of every kind of material. He had one thing I lacked: amethyst, available only in a

hard-to-reach dimension which HT alone had so far managed to visit. My alchemical factory could

mass-produce almost anything, but only if it started with a small sample of the target material, so I

could not make my own amethyst without first getting my hands on at least one block of the stuff.

So I offered HT a trade that, to him, must have seemed generous and too good to refuse, but

in which my sacrifice was trivial: 81 diamonds (nine “blocks”) for 9 shards of amethyst (one block).

2

The diamonds I spent meant nothing to me, but the trade revealed that even to a demi-god who had

exploited every mod to its fullest, 81 diamonds was still a small fortune. With my exploit, I had

completely subverted the notion of a fair trade.

But this is not really a story about me and my alchemical trickery. What I want to highlight

with this anecdote is that these unusual transformations of Minecraft’s play dynamics were enabled

by the vibrant—but at times chaotic—modding practice and community that has coalesced around

Minecraft. Almost since the game first appeared as a playable work-in-progress in 2009, players have

been hacking and making changes to the code, tweaking rules and adding features. Nearly 10 years

on, Minecraft is a multi-billion-dollar property with hundreds of millions of users. All throughout,

the work of fan modders has been central to Minecraft’s evolving articulation as a product and

cultural phenomenon.

This is their story.

2

My actions were not entirely beyond the spirit of play on our particular server. The play environment was

highly experimental and not competitive in nature. I also made a disclosure to the server administrator about

my discovery and subsequent activities. After the trade was concluded, I let HT in on the secret, as it felt

cynical and opportunistic not to.

4

1.2 Background on Minecraft

Figure 1-1. Minecraft gameplay screenshots. Left: the player explores the surface of a world made of cuboids. The

player's various mining tools and building blocks are shown in the toolbar at the bottom. Right: players can explore vast

underground cave systems in order to find resources to mine, but have to watch out for monsters that spawn in the

darkness, like this explosive green Creeper. (Screenshots by N. Watson.)

As of the mid-2019, Minecraft (Mojang AB, 2011) is the second-best-selling video game of all

time, with over 176 million copies sold across all platforms (Dent, 2019). It has even been adapted

for practical use by educators, national governments, and United Nations agencies. It is a single- or

multi-player “sandbox game” played in an open-ended virtual space (a “WORLD” or “MAP”)

3

where

players explore (Figure 1-1, above), craft tools (Figure 1-2, below), harvest resources, fight monsters,

hunt for treasures, erect structures out of cubic blocks, create art, and construct elaborate machinery.

Broadly speaking, there are two ways to play: in SURVIVAL MODE, players must harvest resources

from the monster-ridden environment and use them to make food, shelter, and equipment, perhaps

eventually reaching the point of constructing massive palaces; in CREATIVE MODE, all objects and

materials are available in unlimited quantity to invulnerable players, so that they can build freely as

if with a virtual Lego set.

Minecraft’s rise to popularity occurred while the product was still under iterative

development, so that millions of early adopters played an incomplete game, in which major features

were promised but not yet implemented. In fact, although the official release dates to November

2011, the first playable prototypes were made publicly available in 2009, and quickly became hugely

3

These and other terms that appear in SMALL CAPITAL LETTERS are defined in the Glossary.

5

popular, with over a million sales almost a year before official release (Orland, 2011). This means

that while Minecraft still had the form of an unfinished, evolving niche/indie game, it had the

uptake of a mainstream blockbuster.

The presence of significant bugs and the addition of new content every few months meant that game

play was constantly in flux. Even while the game’s developers have gradually, incrementally shaped

the game towards a finished form—a process which has continued long after the game was declared

“finished” in 2011—independent coders and artists in the player community have also produced

hundreds of unofficial bug-fixes, hacks, mods, texture packs, plug-ins, and companion programs of

their own. This player-made content, which far outweighs the official content in terms of sheer

quantity, has come to play a key role in defining Minecraft’s identity as both a commercial product

and a cultural object. Far from remaining on the periphery or in the realm of a minority of hardcore

fans, the creation and use of player-made mods occupies a central position in this play ecosystem.

Figure 1-2. The crafting interface. This screenshot shows a user interface that allows common materials to be crafted into

more advanced tools. Here, seven wooden sticks are being used to build three pieces of ladder. The darkened background

shows part of a player-built home, which acts as a safe place to store materials and craft items. (Screenshot by N. Watson.)

6

1.3 Variants and lineages of Minecraft

Duncan (2011) speaks of there being “many Minecrafts” due to the game’s iterative open

alpha and beta development, which gave rise to different play practices in each version. This is

further discussed in Chapter 4. However, in the years since Duncan’s observation, officially

differentiable EDITIONS (not to be confused with VERSIONS and GAME MODES) of Minecraft have

also proliferated. Microsoft’s purchase of Mojang AB in 2014 further reshaped the landscape of

Minecraft editions. I offer the following descriptions of these editions to provide clarity for

subsequent discussions. Figure 1-3 (page 9-10) shows the timeline of three major “lineages” of

Minecraft—based on implementation and platform availability—and key modding tools for Java

Edition, the Minecraft variant under investigation here.

1.3.1 Java Edition

The original edition of Minecraft, released by the author in its earliest form in 2009 and

officially published as complete in late 2011, was coded using the Java programming language.

Although it is sometimes referred to as the “PC version,” that label is misleading since, in the case of

games, this usually means that the software is designed for Microsoft Windows. Minecraft: Java

Edition runs on Windows, Mac OS/X, and Linux, thanks to Java’s platform-independent nature.

While this variant was originally simply “Minecraft,” Microsoft rebranded it to “Java

Edition” in 2017, concurrently with the rollout of their new Bedrock-based versions (see below).

Java Edition continues to be the easiest variant to mod and thus the target of most modding.

Furthermore, its modding practices have a long history and arose in an almost entirely organic and

fan-driven manner, with little to no prescriptive guidance from Mojang.

The focus of this research is Java Edition modding. When the word “Minecraft” is used

herein without other qualification, it will refer either to the general family of Minecraft games (i.e.

all variants), or specifically to Java Edition, but not to Bedrock editions. (Readers who are well-

7

acquainted with the Minecraft franchise may note that this usage differs from Microsoft’s current

preferred branding, in which the unqualified name “Minecraft” means Bedrock.)

1.3.2 Pocket and Bedrock editions

Minecraft: Pocket Edition (MCPE) for mobile devices first appeared in late 2011 on Android

and iOS, just as Java Edition (which was the primary product at the time) was gearing up for its

official 1.0 release. This mobile edition was built on a codebase called the “Bedrock codebase” or

“Bedrock engine,” written in the C++ programming language, and was developed concurrently with

Java Edition. The Windows 10 Edition, first released mid-2015, was derived from MCPE and

foreshadowed Microsoft’s plans to expand the Pocket Edition family to non-mobile platforms. In

September 2017, they did just that with the “Better Together” update, which allowed cross-platform

multiplayer gaming between mobile devices, Windows 10 PCs, Xbox One, and Nintendo Switch.

The game on all four of these platform families was rebranded as “Minecraft” with no subtitle (with

the original game being renamed Minecraft: Java Edition at that time). Since the Xbox One and

Nintendo Switch had previously had their own Minecraft versions not related to Bedrock/MCPE,

the “Better Together” update also supplanted those. The Minecraft Wiki

(https://minecraft.gamepedia.com) and much of the player community often refer to all of the

Bedrock-based versions collectively as “Bedrock Edition,” although the administrators of

MinecraftForum.net (an affiliate site of the Wiki) advocate for using Microsoft’s official nomenclature:

There is no such thing as "Bedrock Edition" so we will not be using that name. Bedrock

is the name of the underlying platform used by the cross-platform Minecraft game. The

game built on the Bedrock platform is called Minecraft and that is the name we are

using. (citricsquid, 2017)

Because C++ programs are compiled into native code for each target platform, they can be

faster and more efficient than Java programs at performing similar tasks; Java is sometimes bogged

down by the VIRTUAL MACHINE’s increased overhead. Since processor lag is a perennial problem for

modded Minecraft—especially in multiplayer—the idea of an efficient C++ implementation was

8

celebrated by some server owners and modpack creators. However, C++ programs resist the kind of

wide-open hacking that has made Minecraft modding so pervasive and vibrant, because the

compiled binary code is much more difficult to reverse-engineer than Java BYTECODE. Furthermore,

without the help of a comprehensive modding API,

4

modders would have to compile and release

their mods for each target platform.

MCPE/Bedrock’s affinity with mobile and touch-screen devices also gives rise to play styles

that are markedly different from those seen in Java Edition (see Subsection 2.5.3).

1.3.3 Legacy console editions

A third family of Minecrafts was developed in C++ (but separately from Bedrock) from 2012

onward by 4J Studios for gaming consoles—Xbox 360, Xbox One, PlayStation 3, PlayStation 4,

PlayStation Vita, Wii U, and Nintendo Switch. The Xbox One and Nintendo Switch versions from

this family have been discontinued as they were supplanted by Bedrock versions (see above).

Furthermore, in the flurry of rebranding that accompanied the Better Together update, the

remaining console versions were collectively dubbed Legacy Console Edition(s).

1.3.4 MinecraftEdu and Minecraft: Education Edition

MinecraftEdu began as a mod of Java Edition designed for classroom use and distributed

from 2011 to 2016. The developer, TeacherGaming, had a license from Mojang to sell MinecraftEdu

as a separate product. Microsoft purchased MinecraftEdu in 2016 and replaced it with a new

product, Minecraft: Education Edition (MCEE), which is based on the Bedrock engine. Although I

will not be discussing MinecraftEdu/MCEE in detail (and it is not shown on the timeline diagram in

Figure 1-3), it deserves mentioning as an example of a total conversion mod being re-absorbed by the

game’s original developer, much like the example of Half-Life mod CounterStrike that often comes up

in existing literature on modding (e.g. Kücklich, 2005). Furthermore, the majority of scholarly work

4

In this context, an Application Programming Interface (API) would be a set of programmed tools and

standards that would allow modders to easily write code that communicates with core Minecraft components.

9

on Minecraft so far has come from the fields of education and child development, and much of that

work is specific to the educational editions (see Subsection 2.5.2).

Figure 1-3. (Page 10) Timeline: 10 years of Minecraft development, showing the major updates and changes for the three

key edition-families, as well as the rise and fall of fan-developed modding toolsets and frameworks for Java Edition.

10

11

1.4 Beginning to define "mods"

Minecraft mods are mods because that's what the community calls them.

Translating that terminology to another game is a pain. Each community has a

different meaning and language. Trying to define it is a fool's errand.

—Alta, Minecraft modder

Let us, then, embark on a fool’s errand.

“Mod” is short for “modification,” and “modding” is the practice of creating such a

modification, but what actually constitutes a mod and modding is ambiguous and contested. For the

purposes of this research, I propose the following definition:

A mod is a piece of software or a body of digital data that modifies the process and

experience of a digital game, such that it differs tangibly from its original form, on

either a procedural level or a cultural/experiential level.

This is similar to the emic (internally-understood) definitions espoused by modders whom I

interviewed for this study. For instance, when asked to define “mod,” modder ScriveShark

responded:

Any modification to the content or mechanics of a game through the manipulation of a

game’s files or software, including adding files to be processed in the normal execution of

the software and in ways the software was designed to expect.

Exactly what constitutes a mod, and what is involved in making one, can vary from one

game to another. The process of Minecraft modding involves reverse-engineering the original

software product into source code, making changes to that source code, recompiling, and posting the

new files on internet websites for players to download and “inject” into their own copies of the

game. Over time, members of the community have developed utilities to automate the reverse-

engineering and code injection parts of the process, such that modders can focus on the actual

content they wish to alter, and players with minimal technical knowledge can install pre-built mods

on their own computers.

12

Typical Minecraft mods might add a new kind of machine or a new species of animal to the

game, or might alter the user interface to serve some utility function, such as automatically

highlighting dark areas of the world where dangerous monsters could appear. Figure 1-4 (page 14)

depicts gameplay with some popular mods. In discussions, players distinguish between modded

Minecraft and “VANILLA”—meaning non-modded standard Minecraft, although we will soon see

(in Chapter 4) that even without mods, there is no one standard Minecraft.

Minecraft mods come in many shapes and sizes. I provide the following list in order to give a

picture of the sorts of things that mods can do, and to provide reference points for the discussions to

follow. These categories are of course socially constructed, unstable, and inconsistently applied by

scholars and players alike—with much of the confusion stemming from the differences between

games. The categories I describe here are grounded in my modder-informants’ own understandings

of these terms, based on interview responses and the organization of mods at the Better Than

Minecamp convention described later on in Chapter 5.

Texture packs straddle the boundary between mod and not-mod. Since they are supported

natively by the vanilla software, they do not alter the running code in any way. They can change the

appearance of blocks, items, and creatures, but usually have no effect on gameplay itself.

5

New

textures can be designed using widely available image-editing software, and are easily distributed

online, downloaded, and loaded into the game. In Minecraft version 1.6.1 (July 2013), texture packs

were folded into the more expansive concept of RESOURCE PACKS, which include the ability to alter

simple three-dimensional shapes, sound effects, music, splash screens, and fonts.

6

According to my

informants, Minecraft players tend not to call these mods at all, while admitting that texture swaps

5

As usual, there are boundary cases. Swapping in a texture file with transparent pixels for a block that

Minecraft considers to be opaque can create a sort of X-ray effect that allows the player to see through cave

walls—a boon for diamond-hunters but definitely a circumvention of the intended rules of play.

6

Version 1.13 (July 2018) introduced data packs, which allow further customization of Minecraft gameplay

without any actual coding. Using data packs containing JSON files (see glossary), players can do things that

were previously only possible with code-altering mods, such as defining custom crafting recipes or changing

the rules for generating in-world dungeons and loot chests. Data packs came on the scene towards the end of

my research and are not analyzed in detail here.

13

in other games can be considered mods, based primarily on whether or not the game has a built-in

function to support them. According to ScriveShark, “There should be a change or addition to the

mechanical operation of the game. Adding more paintings would be a mod, or adding more cards or

even variations of visuals, but simply replacing the appearance or sound of things […] is more of a

customized localization” (emphasis added; see glossary for LOCALIZATION).

Atmospheric mods, similar to texture packs, alter the look and feel of the Minecraft world,

without radically changing the underlying game mechanics. These mods, however, require actual

changes to the code because they add new artifacts and scenery to the world, such as new plants and

animals, rather than re-skinning existing ones as texture packs do.

Unofficial patches are designed to fix bugs and performance problems in the vanilla

product. Fans make these when they do not want to wait for the developer to get around to issuing

official patches. This was particularly common in Minecraft's pre-release days of open Alpha and

Beta testing.

Tweaks and rebalancing mods attempt to address what some players perceive as flaws in

game design. One of the most common examples is RECIPE-tweaking, in which the materials

required to craft certain items are changed to make those items either easier or more difficult to

create.

Gameplay mods add entirely new game mechanics and/or significantly alter existing ones.

These are usually the largest and most complicated mods. In extreme cases, these mods amount to

what Scacchi (2011) calls total conversions, particularly if they replace the original mechanics. A

gameplay mod typically has its own trajectory of player progression—its own learning curve,

materials to acquire, and skills to master. Tech mods and magic mods are two broad sub-genres of

gameplay mod. The former focuses on creating large factories of complex, interconnected, industrial

machinery, with the goals of automation, optimization, and multiplication of resource-based wealth

(Figure 1-4, bottom). Magic mods are quite similar to tech mods, but they have a fantasy/arcane-arts

14

theme instead of an industrial/technological theme. Tech and magic mods also often add entirely

new spaces (called dimensions) to the game, e.g. a mystic forest realm that can only be reached

through an eldritch portal, or a lunar colony accessible by rocket ship.

Figure 1-4 . Minecraft gameplay screenshots, featuring mods. Top: One popular mod, Millénaire, adds autonomous

villagers who gather their own resources, build their own houses, and will trade goods with the player. Bottom: Popular

“tech mods” add industrial machinery and lead players to construct massive automated factory systems for the production

of useful materials. Pictured here are pipes (Thermal Expansion), storage tanks, and steam engine boilers (RailCraft) that

have been damaged by a recent explosion, due to a malfunction in the water-pumping system. (Screenshots by N. Watson.)

15

Utility and user interface mods are designed to facilitate interaction between the user and

the game. One example is InvSort, a mod that can automatically sort and organize a player's

inventory with a single keypress.

Fans have created several external programs that are not strictly mods in that they do not

change the running code for the game, but they still modify the gameplay experience. The most

notable of these are the map editing programs that provide players with powerful tools to create and

edit Minecraft worlds from outside the game itself.

Finally, custom maps are sometimes called mods even though they may be created entirely

within the vanilla program: a player uses the in-game “Creative Mode” building tools to create a

space for others to explore—perhaps with puzzles or prescribed adventuring goals. The map or SAVE

FILE associated with this world is then distributed online through sites like MinecraftForum.net and

PlanetMinecraft.com for others to download and play with. Nothing about the game program has

actually been changed, but some commentators apply the “mod” label nonetheless (e.g. Christiansen

[2014] on the “Skyblock” mini-game; see Section 2.4 for further discussion). The temptation to refer

to custom maps as mods may come from first-person-shooter (FPS) modding in which the virtual

spaces (maps) are immutable by vanilla means, so all custom maps are de facto mods. Since modding

of commercial games—and academic work on the subject—largely originates with FPS games, it is

not surprising that their terminology sticks even as context changes. Furthermore, while a custom

map can in principle be designed in-game, it is often much easier to use a fan-made external editor

program like MCEDIT. Finally, by radically re-orienting play goals around a different environment

with different constraints, some custom maps transform Minecraft in a way akin to what total

conversions accomplish, creating a subjective player experience that is difficult to distinguish from

what more prototypical mods do. However, as with texture packs, Minecraft players are reluctant to

refer to custom maps as mods.

16

Machinima—the use of video game engines and video capture software to create movie-like

narratives—is often lumped together with modding (see e.g. Scacchi, 2011), yet it works purely on

the cultural/experiential level and creates an end product of a wholly different, non-game media

form. For instance, watching the comedic video series Red vs. Blue (Rooster Teeth Productions,

2003) is clearly a different sort of activity from playing Halo: Combat Evolved (Microsoft Game

Studios, 2001), the game environment in which the series was “filmed.” Therefore, although

machinima will come up in discussions of modding literature to follow, I do not classify it as a form

of modding and do not investigate the rich creative domain of Minecraft machinima in this study.

1.5 Modding frameworks

The earliest form of Minecraft modding involved a technique known as “jar modding,” in

which modders hack the game’s core files. This process is described further in Chapter 4.

However, various platforms, tools, and APIs were created by Minecraft fans to facilitate

modding and to make different mods compatible with each other. I briefly introduce these here so

that their names will be familiar when they reappear in the subsequent pages.

This research focuses mainly on mods that are made using the Forge API

(https://minecraftforge.net), a powerful and popular mod-making framework that has been around

since 2011 (see Figure 1-3 on page 10). Forge is designed to reduce (and, increasingly, eliminate) the

need for most modders to directly edit Minecraft’s core code; instead, they create modules that can

intervene, via channels facilitated and sanctioned by Forge, to alter how Minecraft works. Forge was

initially used alongside a separate utility called ModLoader, which is what made modularity

possible, but ModLoader was succeeded by Forge’s own built-in mod loader, FML. More detail is

provided in Chapter 4.

Making mods using Forge involves writing Java source code, but at least one tool exists that

positions the modder at a distance from the code itself. MCreator is a mod-developing tool

developed by Slovenian software startup Pylo. Backed by machine-generated, Forge-compatible

17

Java code, it offers a graphical interface with which modders with minimal programming experience

can create mods by piecing together the sorts of “elements” that mods typically add—e.g. new

blocks, tools, or administrator commands. While this model of assembling mods out of a collection

of templates does not allow for as much flexibility as direct Java programming, MCreator allows

access to its Java back-end for advanced modding.

Jar modding and Forge—with or without MCreator—are not the only ways to go about

modding, but almost all mods that add new blocks to the game (and many other mods besides) are

made using one of these two methods. Other methods, described briefly below, are not considered in

this research except in passing. A system called LiteLoader (https://www.liteloader.com) is

intended to provide a “minimally invasive” way to install mutually-compatible mods, particularly

CLIENT-side mods that don’t change core game mechanics, like user-interface tweaks (thus,

LiteLoader-modified clients are compatible with vanilla SERVERS). The Bukkit API, along with its

predecessor hMod, embody a very different modding paradigm. These alter Minecraft SERVER code

to change game mechanics, but are limited in what they can accomplish. Bukkit plugins can do

things like adding new typed administrator commands, providing scripted encounters with NPCs

(non-player characters), implementing trade systems, enforcing property ownership regimes on

multiplayer servers, teleporting players around, and changing world generation rules. The Minecraft

“mini-games” industry, with its Hunger Games-themed deathmatch tournaments and Skyblock

competitions (and many other Minecraft-based play scenarios), relies largely on Bukkit mods to

implement special game rules. What Bukkit cannot do is add new kinds of blocks or machines, or

otherwise make any changes that would need to be reflected in each player’s client program. This is

both a limitation and an asset: it means that people can play on Bukkit servers with vanilla clients. In

fact, hundreds of thousands of people who regularly play on multiplayer servers are themselves

running vanilla Minecraft, and may be completely unaware of the fact that the servers they play on

are heavily modded.

18

The term “Bukkit” refers to an API for making Minecraft plugins. The actual server

wrapper—the component that allows those plugins to talk to the core Minecraft program—is called

CraftBukkit, but it has been defunct and unavailable since 2014. However, other Bukkit-compatible

server wrappers such as SpigotMC have taken its place.

Regardless of the platform or API in use, most Minecraft modding efforts ultimately rely on

the Minecraft Coder Pack (MCP), a suite of tools for converting Minecraft binary files into human-

readable Java source code. A few, like the Fabric system (https://fabricmc.net/) that emerged in late

2018, implement their own toolchains for these purposes.

1.6 Blueprint

1.6.1 Purpose and scope

The overarching goal of this work has been to provide a description of the culture of a

community of Minecraft modders and their practices of modding, including the details of the

technical and social work performed by modders. I have further sought to determine the sites of

contested meanings—among modders, between developers and modders, and between modders and

players; how these conflicts arise and are mediated; and what social, cultural, and discursive

resources are mobilized by stakeholders. These findings serve to add a new perspective to ongoing

scholarly efforts to explicate the causes and circumstances—social, cultural, and technical—that

have given rise to, and sustained, active fan participation in the co-creation of Minecraft.

These purposes are revisited in Chapter 3, where they are connected to my research

questions and theoretical frameworks.

1.6.2 About this document

The current chapter has served to introduce Minecraft and the concept of mods. Although

modding has a deep and rich history, with roots in early 1990s first-person-shooter (FPS) games, I

have refrained from recapitulating a comprehensive history and typology of modding in general, as

19

this work has already been accomplished by others (e.g. Nieborg and van der Graaf, 2008; Sotamaa,

2009; Sihvonen, 2011; Champion, 2012a; Christiansen, 2012).

In the following chapter (Chapter 2 – Review and Commentary on the Literature), I

undertake a review of current academic thought in the areas of fan studies and participatory culture,

before proceeding to a brief discussion of prior work on game modding. Subsequently, I summarize

existing scholarship specific to Minecraft, with particular attention to participatory production and

modding, followed by a commentary on areas that the literature has yet to address.

Chapter 3 – A Workbench of Theory and Method introduces the major theoretical frames

that I have used to make sense of Minecraft modding, setting the stage for their reappearance in

subsequent chapters. Here I also outline my methodological approach and the contours of my

research activities.

In Chapter 4 – Settling Minecraft, I trace the story of how early Minecraft came to be

“settled” by innovative player practices and “soft modding,” with player improvisations gradually

becoming fully implemented and integrated into the software. “Hard” modding is described as

having developed along a similar trajectory, from ad-hoc improvisations to established frameworks

and methods.

Not satisfied with terrestrial frontiers, I take a virtual journey to a space station in Chapter 5

– Better Than Minecamp: An unconventional convention. This is a first-hand look at an online

event from 2017 that celebrates Minecraft modding while also mocking (with varying degrees of

playfulness or severity) Minecamp, Mojang’s official Minecraft convention. Here we will see a

snapshot of the “settled” state-of-the-art of Minecraft modding, including how gleefully unsettled it

still is in many ways. We will also get a preview of some of the key issues on the minds of prominent

modders.

Back on Earth, Chapter 6 – Operational Logics and the Rationalization of Modding delves

into the technical bits of Minecraft and modding, and considers how modders grapple with this

20

technical work. I expand Wardrip-Fruin’s (2009) notion of operational logics into a model that extends

through the domains of computation, programming, and play, to provide an account of how

modding practices have been subjected to increasing strategic rationalization.

Chapter 7 – Modding Discourses examines the role that modders’ discursive activities play

in innovating, settling, contesting, and remaking modding practice. A brief summary of the means

that modders use to communicate is followed by a study of how modding is contested among

modders (not just between modders and commercial developers), how “proper” practices are

constructed, and how gaming capital (Consalvo, 2007) circulates within the community.

Programming practices themselves are also considered as a kind of discourse.

In the Conclusion, I consider the potential lessons of this research for the co-creative

development of video games. Following a discussion of potential directions for future research on

Minecraft and game modding, I focus critical attention on notions of Minecraft as an exceptional,

endlessly extensible platform for constructing play experiences. I close with some final thoughts on

the oscillations between tactical and strategic modes of cultural production.

I have included three appendices to help illustrate the occasionally-opaque technical

concepts discussed herein. Appendix A – A Very Brief Summary of Object-Oriented Programming

Concepts in Java provides a crash-course in the major jargon and main concepts of Java

programming, while Appendix B – Custom Block Mod Code presents an annotated inventory of all

of the source code for a simple example Minecraft mod. Appendix C – Forge Hooks: Registries and

events, provides an explanation of some of the inner workings of the Forge modding framework that

are mentioned elsewhere in the paper.

The use of SMALL CAPITAL LETTERS indicates a technical term from Minecraft or

programming that has a specific definition for the purposes of this text; each such term has a

corresponding entry in the Glossary. (Small capital letters are only used when the term is initially

introduced.)

21

To protect the privacy of research participants, their names have been changed in these

pages, except in cases where they requested, or gave permission for, identification. The names of

some mods have also been obfuscated for the same reason. Non-participant public persons in the

Minecraft community, for whom all data reported here is derived from publicly-accessible archives,

are (in most cases) identified by the screen-names they actually use.

7

It is common for documentaries to begin with a disclaimer that the opinions expressed by

interviewees are their own, and do not necessarily reflect those of the author or publisher. While that

is true of this document, it is equally important to note that my opinions as the author are my own,

and the participation of any research informant or interviewee does not imply that they endorse or

agree with my conclusions.

Technical data and information regarding Minecraft gameplay features are valid for

Minecraft: Java Edition versions up to at least 1.12.2, which was released September 18, 2017.

To ensure the long-term availability of web-based sources, URLs for Internet Archive

Wayback Machine (http://web.archive.org) versions of referenced web pages are provided where

practical (archived versions are not provided for general website URLs, downloadable files, videos,

articles hosted on an academic journal’s website, and resources that already have a DOI or database

presence). Where a suitable snapshot of a web page did not already exist in the archive, a new one

was created. The inclusion of an Archive.org link does not necessarily mean that the original

document is no longer available. For archive links in this document, the original URL always forms

the second part of the archive link. To make it easier to separate out the original addresses, the

portion corresponding to the original URL is underlined in this document’s footnotes. In the

bibliography, archive URLs are provided in italics at the end of applicable bibliographic entries.

7

I have maintained the typographic conventions used by individuals in rendering their own screen names. For

instance, if they do not normally capitalize the first letter of their screen name, I also do not capitalize it in this

document, unless it appears at the beginning of a sentence.

22

II. REVIEW AND COMMENTARY ON THE LITERATURE

2.1 Under the influence: Mass media and audience passivity

Of course the media affect emotions and behavior. That is why people use them.

—Jeffrey Goldstein (2005, p. 350)

I begin by addressing an assumption, present in both popular discourse and significant

bodies of scholarship—especially early-to-mid-20

th

century cultural studies—that mass media entails

a sharp division between powerful, corporate media producers on the one hand, and powerless

consumer audiences on the other, who are the passive recipients of whatever “messages” those

producers choose to disseminate. The flow of information is seen as moving in one direction only—

from the media elite to the masses. The discourses favoured by the elite must therefore dominate, so

that they have unmatched persuasive influence over the creation and consumption of culture. The

“culture industry,” as Adorno and Horkheimer (1944/2002) originally named it, is hegemony

calculated to produce homogeneity, and consumers are cultural “dupes.”

While Adorno, Horkheimer, and other Frankfurt School theorists had good reason to be

concerned about the possibility of mass media being used to distort truth, encourage docility, and

spread propaganda, the uncompromising cynicism of this view tends to erase the real and

worthwhile work done by the “masses” to interpret, answer, configure, rework, and re-circulate

media objects. Despite decades of discourse to bear this out, the claim of passivity has proven

tenacious, enjoying the occasional resurgence as a go-to assumption for researchers who find

themselves in the position of having to make sense of the next new trend in media.

2.1.1 The spectre of effects studies

Videogames found themselves under this lens from the 1980s to the turn of the century, the

heyday of effects studies (e.g. Anderson & Ford, 1986; Provenzo 1991; Dill & Dill, 1998; Kirsh, 1998).

Highlighting themes of addiction, aggression, delinquency, and violent crime, this research focused

23

on what sorts of messages games were communicating to players (especially children), and what

impact this has on a player’s thought, behaviour, and perception of the world. According to

Provenzo (1991, p. 65), a significant body of work has been devoted to importing two models for

understanding the relationship between television content and aggression—catharsis theory and

stimulation theory—into the realm of videogames. Goldstein (2005) is highly critical of this “willy-

nilly” application of television research, since “video games differ from television and film not only

in their interactivity, but in the nature of their stories, in their open-endedness, and in their ability to

satisfy different needs of their users” (p. 342).

Some discourses feature an odd mixture of psychological experiments that fail to provide

evidence in support of alarmist hypotheses, coupled with vague analysis that seems to try to keep the

anxiety alive by leaving open the possibility of a future verification of the social ills of gaming. Kirsh

(1998) claims a weak, short-term correlation (in children) between playing a violent game and

attributing hostile motives to the actions of others in the real world—a finding that supports the

notion that games have effects (however brief), but offers no substantiation of popular claims linking

teen violence to gaming. Provenzo (1991, p. 70) admits that there is no evidence that games

contribute significantly to deviant behaviour, yet leaves open the door for worry about other

unnamed social and cultural “impacts” of gaming. His claim that “concern about the games is in

fact justified” (1991, p. 50) apparently hinges not on direct demonstration of effects but rather on the

presumption of effects based on game content. The content itself is considered outside of its actual

use context and through reports of an anecdotal nature, which cherry-pick what is most exceptional

and sensational and re-frame it as typical: Provenzo holds up Custer’s Revenge (Mystique, 1982), a

fringe game made by an obscure pornographic games producer for the Atari 2600, as evidence that

videogames “have a history of being sexist and racist” in addition to being violent (1991, p. 52).

While I do not deny that racist and sexist undertones are and have historically been present in many

24

mainstream games (although not generally more so than the average Hollywood blockbuster),

Custer’s Revenge is far from representative of the medium’s offerings.

Williams (2003) argues that the “story of vilification and partial redemption” of videogames

is tied to the social tensions of the times, particularly the conservative anxieties of the 1980s—thus

they probably tell us more about reactionary politics than about games. In fact, the early framings of

games research in terms of violence and addiction may have taken its cue from popular media and

political discourse, such as the U.S. Surgeon General’s infamous 1982 claim that games were

producing “aberrations in childhood behaviour” (Provenzo, 1991, p. 50).

Goldstein (2005), who provides an extensive review of behavioural research on videogame

violence from the 1980s through 2001, is unequivocal in his criticism: “Discussions of violent video

games are clouded by ambiguous definitions, poorly designed research, and the continued confusion

of correlation with causality” (p. 341). Further, “there is no evidence that media shape behavior in

ways that override a person’s own desires and motivations” (p. 350).

Effects studies were not universally negative. Williams (2003) describes “utopian” research

narratives standing in opposition to these alarmist discourses—studies that tried to partially redeem

games by pointing to the ways in which they could educate children, build cognitive skills, or

provide a context for positive social interaction among family members (e.g. Mitchell, 1985).

The uniting feature of effects studies, however, is the presumption of passivity. “Missing

from research,” writes Goldstein in a passage that (unintentionally?) echoes Caillois (1961), “is any

acknowledgment that video game players freely engage in play, and are always free to leave, or

pause. Except in laboratory experiments, no one is forced to play a violent video game” (Goldstein,

2005, p. 353). Effects studies fixate on what media do to us, rather than on the far more exciting

question of what we can do with them.

If anything, it is ironically the theories of creative-participatory media culture, rather than the

tropes of corruption through passive consumption, that are more easily linked to examples of

25

deviance. When in 2013, a nine-year-old boy was arrested in Orlando, Florida for bringing weapons

to school, his father claimed that the boy was indulging in a Minecraft character fantasy, and further

argued that there was no chance that the child would have harmed anyone (Thompson, 2013). The

following year, 12-year-olds Anissa Weier and Morgan Geyser did harm their classmate Payton

Leutner while acting out a twisted fantasy inspired by the “Slenderman”

8

internet fandom. Actual

incidents of concern resemble dangerous live-action fanfictions more than cases of violent

behavioural conditioning. They also remain exceptionally rare, and are seldom explainable in terms

of media fandom alone—serious mental illness being implicated in the case of Weier and Geyser

(Almasy, 2017). It seems that there is not much worthy of true concern for alarmist media

researchers to find in the realm of participatory culture, either.

2.2 Voices from the listeners

The assumption of audience passivity, while tenacious, has been thoroughly dismantled by

decades of research in media and cultural studies, making it more difficult in turn to maintain the

illusion of a clear division between media producers and consumers. Uses and gratifications theory,

typified by the approach of Blumler and Katz (1975), offered the initial rebuttal to effects-focused

thinking by reframing media consumption as an active pursuit. It forms no small part of Goldstein’s

indictment of effects research that was cited above. The turn to participatory culture steps beyond

uses and gratifications, identifying not only the ways in which audiences can resist hegemony, re-

interpreting and re-signifying the meanings offered by media objects, but also how they can become

active participants in shaping mainstream of media texts.

8

The Slenderman neo-folklore meme did not originate with videogames, but with “creepypasta”—short,

homebrew horror stories and images that are shared through online message boards. It has been further

embellished through YouTube videos. However, it has also been the subject of videogames, such as Slender:

The Eight Pages (Parsec Productions, 2012). Minecraft features a Slenderman-inspired monster called an

Enderman. Minecraft is, of course, also the setting for another creepypasta/fanfic custom featuring a

humanoid monster known as Herobrine who, despite having a radically different appearance, is seen in some

stories to operate in a manner similar to Slenderman, and is also often associated with the Endermen (see Gu,

2014, p. 139-140).

26

First and foremost, consuming media is work!

9

Audiences never merely receive, but engage

actively in the construction of something meaningful out of media material, even when there is no

overt experience of resisting cultural hegemony. Stuart Hall (1980/2001) is well known for

describing how audiences apply available cultural codes in understanding media messages—and the

considerable interpretive latitude they have in doing so, producing “oppositional” or “negotiated”

readings as alternatives to the intended (hegemonic) reading. Fiske (1987/2001) tells us that texts are

understood (decoded, interpreted) in terms of their relations to other texts (which may or may not

explicitly reference one another). Readers must therefore do the active work of mobilizing cultural

resources—the knowledge of other texts—in order to construct a coherent reading of the text in

question: every text, through its reading, is always in the process of becoming another text’s

paratext.

Michel de Certeau (1984) argues that media audiences (“readers”) are active in meaning-

making, but marginalized by a productivist discourse of sanctioned and regulated meanings.

Audiences are nomadic “poachers,” living and “making do” on the periphery of texts, employing

"tactics" (de Certeau, 1984) of reinterpretation to construct their own readings—what Murray (2004,

p. 20) calls “semiotically self-determining.”

Jenkins (1992) borrows this metaphor of poaching to describe specific examples of how

television fans engage in a participatory culture, reading and reworking the texts that they consume.

Jenkins finds that fans are constantly asserting their right to renegotiate and redefine the terms of

media consumption, and to freely attach their own meanings, or reject those offered by producers.