UC Berkeley

UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations

Title

Rumor Has It: The Press Conditional in French and Spanish

Permalink

https://escholarship.org/uc/item/5sm3n421

Author

Arrigo, Michael

Publication Date

2020

Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation

eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library

University of California

Rumor Has It: The Press Conditional in French and Spanish

By

Michael C. Arrigo

A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the

requirements for the degree of

Doctor of Philosophy

in

Romance Languages and Literatures

in the

Graduate Division

of the

University of California, Berkeley

Committee in charge:

Professor Mairi-Louise McLaughlin, Chair

Professor Richard Kern

Professor Andrew Garrett

Summer 2020

1

Abstract

Rumor Has It:

The Press Conditional in French and Spanish

by

Michael C. Arrigo

Doctor of Philosophy in Romance Languages and Literatures

University of California, Berkeley

Professor Mairi-Louise McLaughlin, Chair

In journalistic texts in both French and Spanish, the conditional may be used to report an

unconfirmed fact, akin to the use of allegedy in English, as in (1) and (2):

(1) La justice pénale américaine enquêterait sur General Motors

‘The Justice Department [would be investigating] General Motors’

(2) Según los datos en poder de este periódico, un informe de Hacienda acreditaría

muchos de los obsequios y confirmaría los datos del ex gerente

‘According to information in possession of this newspaper, a source from the

Treasury [would substantiate] many of the gifts and [would confirm] the former

director’s information’

In French, this use of the conditional has accumulated many names, one of which is the

conditionnel de presse. In Spanish, it is most often referred to as the condicional del rumor. I

refer to both as the press conditional given the construction’s association with journalistic

language in both French and Spanish. While this use of the conditional has been extensively

studied in French, its Spanish counterpart has only recently begun to receive closer attention

from scholars, much of it in the shadow of prior work undertaken on French. This dissertation

addresses this gap by proposing a study that allows for a more thorough treatment of the

construction in each language using an extensive news corpus. Not only does this study provide

new data for Spanish, it provides a comprehensive examination of the press conditional in

newswriting in each language, which, until now, was lacking in both French and Spanish.

In Chapter 1, I present an overview of the uses of the conditional in French and Spanish. I

then focus on the press conditional, its history and its prescriptive status in each language. I also

review previous theoretical models of the press conditional and previous work on the

construction in journalistic texts. In Chapter 2, I present my methodology. I describe my

bilingual corpus consisting of a constructed week’s worth of editions of two French and two

Spanish newspapers: Le Monde, Libération, El Mundo and El Periódico de Catalunya. I then

demonstrate the paraphrases I use to extract tokens of the press conditional from the corpus.

These combine the appropriate indicative tense with adverbial markers paraît-il ‘it seems’ in

2

French and por lo visto ‘apparently’ in Spanish. I then outline the analytic framework through

which I examine the data. I approach the press conditional from the perspective of register,

examining its use in journalistic texts in the light of their communicative aims. Since the primary

aim of journalistic texts is to represent the truth, I understand the choice to use the press

conditional as one made with consideration for precise writing and accurate reporting, which are

the means by which journalists establish credibility.

In Chapter 3, I first examine the forms and frequency of the press conditional in French. I

find that the data here bears out prior claims in the literature: the present conditional is most

frequent with a present reading, while the past conditional is used for past events. I confirm that

the present conditional with a prospective reading is rare, as it is not present in the corpus. I then

analyze how the press conditional is used within the newspapers. I find that article type is not

explanatory with respect to the use of the press conditional in French. Rather, I draw a distinction

between conditionals serving to report information (reporting conditionals) and those that serve

to reprise discourse (discursive conditionals). This distinction is shown here to correlate with

article type, when a high-level split between news and commentary is made. Reporting and

discursive conditionals are found at relatively similar rates in news articles, while reporting

conditionals are rare in commentary, unlike discursive conditionals. The press conditional also

frequently accompanies quantification in reportative contexts in journalistic texts. Discursive

conditionals prove interesting because of their rarity in commentary in Libération and their

relatively higher frequency in Le Monde. I find that Le Monde’s more extensive use of the

discursive conditional in its commentary articles serves to signal a consistently journalistic style

while also demonstrating that the press conditional appears to be a stereotypical feature of

journalistic writing in French. Finally, I argue that, as used in journalistic texts, the press

conditional can be seen as a marker of non-prise-en-charge.

In Chapter 4, I begin by providing the forms and frequency of the press conditional in

Spanish. I note that the press conditional in fact encompasses the press conditional to mark both

inferences and reported information. I provide a tabulation of the frequency of each use as well

as an overview of their functions within the Spanish corpus. I then examine the temporality of

each. I find that the present conditional may refer to present and past states, as well as future

events and states. Notably, I confirm that present conditionals marking reported information do

not require a future time marker to trigger a prospective reading (as is the case in French) in

Peninsular Spanish. I then account for the use of the press conditional in Spanish as a function of

article type. I find that in the case of polls and scientific articles the presence of the conditional

may actually reflect the presence of scientific discourse within the pages of a newspaper.

Conversely, I argue that in the case of articles on official misconduct and criminal activity, the

press conditional’s efficiency in marking uncertainty in sensitive contexts may override

prescriptive discouragement of the press conditional. I end by arguing that more diachronic and

synchronic studies across journalistic, scientific and legal text types may better clarify the

reported and inferential uses of the conditional in the Spanish press and also more generally.

In Chapter 5, I compare the forms, frequencies and temporalities of the present and past

conditional in French and Spanish. I then examine the use of the press conditional in its

capacities to convey reported information and/or inference. To the extent that it is a marker of

reported information, I argue that it constitutes a special kind of reported speech in journalistic

writing. I find that in its speech reporting function, the French press conditional implies an

element of subjectivity not seen in its Spanish counterpart. On the basis of the common use of

the press conditional to mark inference in Spanish, I examine tokens in French that appeared to

3

convey inference. I argue that this function, while numerically marginal, requires further study. I

then compare the press conditional at the level of the article, at the level of the newspaper and at

the level of the language itself. I recall that while article type can be used to explain the use of

the press conditional in Spanish, its use is more generalized in French. With respect to

newspapers, I show that the press conditional reflects little of Libération and El Periódico’s

journalistic practices. The press conditional has what one might call a performative function in

Le Monde and is a pragmatic outgrowth of El Mundo’s investigative reporting. This points to the

varying capacity the press conditional has in helping shape a newspaper’s journalistic identity.

Finally, I conclude with a reflection on the fact that the press conditional is not only a

stereotypical feature of French journalistic language, it is also on its way to becoming such a

feature in Spanish. Thought of this way, it is not just a register feature but potentially a stylistic

one as well.

i

TABLE OF CONTENTS

1 BACKGROUND AND REVIEW OF THE LITERATURE ..................................... 1

1.1 Rumor and Romance: The Conditional for Unconfirmed Reports in the News .............. 1

1.2 Form and Values of the Conditional in French and Spanish ........................................... 5

1.2.1 The Forms of the Conditional in French and Spanish ..................................................... 6

1.2.1.1 The Present Conditional in French .................................................................................. 6

1.2.1.2 The Past Conditional in French ........................................................................................ 7

1.2.1.3 The Present Conditional in Spanish ................................................................................. 8

1.2.1.4 The Past Conditional in Spanish ...................................................................................... 9

1.2.2 Values of the Conditional in French and Spanish .......................................................... 10

1.2.2.1 The Temporal Conditional in French and Spanish ........................................................ 10

1.2.2.2 The Hypothetical Conditional in French and Spanish ................................................... 11

1.2.2.3 The Attenuating Conditional in French and Spanish ..................................................... 12

1.2.2.4 The Press Conditional in French .................................................................................... 13

1.2.2.5 The Press Conditional in Spanish .................................................................................. 13

1.2.2.6 Inferential Uses of the Conditional in French ................................................................ 15

1.2.2.7 Inferential Uses of the Conditional in Spanish .............................................................. 16

1.2.3 Conclusion ..................................................................................................................... 18

1.3 The Press Conditional in French and Spanish ............................................................... 19

1.3.1 Previous Literature on the Press Conditional in French ................................................ 20

1.3.2 Previous Literature on the Press Conditional in Spanish ............................................... 27

1.3.3 Studies of the Press Conditional in Journalistic Texts ................................................... 32

1.4 Research Aims ............................................................................................................... 34

2 METHODOLOGY ...................................................................................................... 36

2.1 The Corpus ..................................................................................................................... 36

2.1.1 The French Corpus ......................................................................................................... 36

2.1.1.1 Le Monde ....................................................................................................................... 37

2.1.1.2 Libération ....................................................................................................................... 37

2.1.2 The Spanish Corpus ....................................................................................................... 38

2.1.2.1 El Mundo ....................................................................................................................... 39

2.1.2.2 El Periódico de Catalunya .............................................................................................. 40

2.1.3 The Corpus: Summary and Coding ................................................................................ 41

2.2 Identifying the Press Conditional ................................................................................... 43

2.2.1 Identifying the Press Conditional in French .................................................................. 43

2.2.1.1 The Temporal Conditional ............................................................................................. 43

2.2.1.2 The Attenuating Conditional .......................................................................................... 44

2.2.1.3 The Hypothetical Conditional ........................................................................................ 45

2.2.1.4 The Press Conditional .................................................................................................... 46

2.2.2 Identifying the Press Conditional in Spanish ................................................................. 47

2.2.2.1 The Temporal Conditional ............................................................................................. 47

ii

2.2.2.2 The Hypothetical Conditional ........................................................................................ 48

2.2.2.3 The Attenuating Conditional .......................................................................................... 50

2.2.2.4 The Conjectural Conditional .......................................................................................... 50

2.2.2.5 The Inferential and Press Conditionals .......................................................................... 51

2.2.3 Identifying the Press Conditional Summary .................................................................. 55

2.3 Analytical Framework ................................................................................................... 56

2.3.1 Register and Style .......................................................................................................... 56

2.3.2 Defining the Aims of Journalistic Language ................................................................. 57

2.4 Conclusion ..................................................................................................................... 59

3 THE PRESS CONDITIONAL IN FRENCH ............................................................ 60

3.1 Form and Frequency of the Press Conditional ............................................................... 60

3.1.1 Frequency of the French Press Conditional ................................................................... 60

3.1.2 Forms of the Press Conditional ...................................................................................... 63

3.1.2.1 The Present Conditional ................................................................................................. 63

3.1.2.2 The Past Conditional ...................................................................................................... 65

3.1.3 Conclusion: Form and Frequency .................................................................................. 65

3.2 The Function of the Press Conditional in French Newspaper Writing .......................... 66

3.2.1 The Press Conditional, Article Type and Genre ............................................................ 66

3.2.2 The Press Conditional: Uncertainty and Confirmability ............................................... 71

3.2.2.1 Two Conditional Types: The Reporting Conditional (RC) and the Discursive

Conditional (DC) .......................................................................................................................... 74

3.2.2.2 Quantifying Conditionals (QC): A Sub-Type ................................................................ 75

3.2.2.3 The Embedding of the Press Conditional Types ............................................................ 76

3.2.2.4 Results of the Classification of Tokens by Type ........................................................... 78

3.2.2.5 Discursive Conditionals in Commentary and Journalistic Style .................................... 82

3.2.3 Conclusion: The Press Conditional as a Distinguishing Feature of Style ..................... 86

3.3 Theoretical Considerations ............................................................................................ 87

3.4 Conclusion ..................................................................................................................... 92

4 THE PRESS CONDITIONAL IN SPANISH ............................................................ 93

4.1 Forms and Frequency of the Press Conditional in Spanish ........................................... 93

4.1.1 Identifying Reportative and Inferential Conditionals .................................................... 95

4.1.2 Forms of the Reportative and Inferential Conditional ................................................... 98

4.1.2.1 The Past Conditional .................................................................................................... 101

4.1.2.2 The Present Conditional: Present Reference ................................................................ 102

4.1.2.3 The Present Conditional: Past Reference ..................................................................... 104

4.1.2.4 The Present Conditional: Future Reference ................................................................. 106

4.1.3 Uses of the Reportative and Inferential Conditional in Spanish .................................. 110

4.1.3.1 Uses of the Inferential Conditional in the Spanish Corpus .......................................... 111

4.1.3.2 Uses of the Reportative Conditional in the Spanish Corpus ........................................ 114

4.1.3.3 The Conditional and Quantification ............................................................................. 116

4.1.4 Conclusion ................................................................................................................... 118

iii

4.2 The Press Conditional in El Mundo and El Periódico de Catalunya ........................... 119

4.2.1 The Press Conditional and Electoral Polls ................................................................... 122

4.2.2 The Press Conditional in Science Articles in El Periódico de Catalunya ................... 125

4.2.3 The Press Conditional and Reports on Crime and Official Misconduct ...................... 127

4.2.3.1 The Press Conditional and Official Misconduct .......................................................... 129

4.2.3.2 The Press Conditional and Crime Reports ................................................................... 132

4.2.4 The Press Conditional: A Pragmatic Alternative ......................................................... 135

4.3 Discussion and Conclusion .......................................................................................... 136

5 THE PRESS CONDITIONAL IN COMPARISON ............................................... 137

5.1 Form and Frequency of the Press Conditional in the Combined Corpus .................... 137

5.1.1 The Present Conditional ............................................................................................... 140

5.1.2 The Past Conditional .................................................................................................... 144

5.2 The Press Conditional as an Evidential Strategy in Journalism .................................. 146

5.2.1 The Press Conditional and Speech Reporting .............................................................. 149

5.2.2 The Conditional as an Inferential Strategy .................................................................. 158

5.3 The Press Conditional and Journalism in French and Spanish .................................... 164

5.3.1 The Press Conditional and the Article ......................................................................... 164

5.3.2 The Press Conditional and Newspapers ....................................................................... 170

5.3.3 The Press Conditional in French and Spanish ............................................................. 172

6 AFTERWORD ........................................................................................................... 174

7 BIBLIOGRAPHY ...................................................................................................... 183

iv

LIST OF TABLES

TABLE 1.1 FORMS OF THE FRENCH PRESENT CONDITIONAL ....................................................... 7

TABLE 1.2 FORMS OF THE FRENCH PRESENT CONDITIONAL ....................................................... 8

TABLE 2.1 CODING OF THE SPANISH CORPUS ................................................................................ 42

TABLE 2.2 CODING OF THE FRENCH CORPUS ................................................................................. 42

TABLE 2.3 CODING OF ARTICLES ....................................................................................................... 42

TABLE 2.4 SUMMARY OF TESTS ......................................................................................................... 55

TABLE 3.1 FREQUENCY OF THE PRESS CONDITIONAL IN THE FRENCH CORPUS ................. 61

TABLE 3.2 FREQUENCY OF THE PRESS CONDITIONAL IN LE MONDE ...................................... 61

TABLE 3.3 FREQUENCY OF THE PRESS CONDITIONAL IN LIBÉRATION .................................... 61

TABLE 3.4 THE PRESS CONDITIONAL AND ARTICLE TYPE IN LE MONDE ............................... 67

TABLE 3.5 CLASSIFICATION OF ARTICLES TYPES AS NEWS AND COMMENTARY ............... 77

TABLE 3.6 DISTRIBUTION OF THE PRESS CONDITIONAL: CORPUS ........................................... 78

TABLE 3.7 DISTRIBUTION OF THE PRESS CONDITIONAL IN LIBÉRATION ................................ 79

TABLE 3.8 DISTRIBUTION OF THE PRESS CONDITIONAL IN LE MONDE .................................. 79

TABLE 4.1 FREQUENCY OF THE PRESS CONDITIONAL IN THE SPANISH CORPUS ................ 93

TABLE 4.2 FREQUENCY OF THE PRESS CONDITIONAL IN EL MUNDO ...................................... 94

TABLE 4.3 FREQUENCY OF THE PRESS CONDITIONAL IN EL PERIÓDICO ............................... 94

TABLE 4.4 FREQUENCY OF THE INFERENTIAL AND REPORTATIVE CONDITIONALS .......... 98

TABLE 4.5 FORM AND TEMPORALITY OF THE PRESS CONDITIONAL IN THE SPANISH

CORPUS ................................................................................................................................ 99

TABLE 4.6 THE CONDITIONAL ACCOMPANYING QUANTIFICATION ...................................... 117

TABLE 4.7 FREQUENCY OF THE PRESS CONDITIONAL ACCORDING TO ARTICLE TYPE ... 122

TABLE 4.8 PRESS CONDITIONALS FOR POLLS IN THE SPANISH CORPUS .............................. 123

TABLE 4.9 INFERENCE AND REPORTATIVE TOKENS WITHIN POLLS ..................................... 124

TABLE 4.10 FREQUENCY OF THE PRESS CONDITIONAL FOR CRIME AND OFFICIAL

MISCONDUCT ................................................................................................................... 128

TABLE 5.1 FREQUENCY OF THE PRESS CONDITIONAL IN THE COMBINED CORPUS .......... 137

TABLE 5.2 FREQUENCY OF THE PAST AND PRESENT CONDITIONAL FORMS IN THE

COMBINED CORPUS ........................................................................................................ 138

TABLE 5.3 FREQUENCIES OF FORM AND TEMPORAL REFERENCE OF THE FRENCH AND

SPANISH PRESS CONDITIONAL .................................................................................... 139

v

Acknowledgements

This project was anything but a single-handed effort. I offer this project in thanks to all of those

who helped me along the way.

Firstly, I offer my thanks to my advisor, Professor Mairi McLaughlin, whose unflagging faith

and tenacity are the co-authors of this study and the underwriters of my degree. I could not have

done this without her.

Furthermore, I would like to offer thanks here

To Professors Richard Kern and Andrew Garrett for their oversight, feedback and

gentleness.

To Mary Ajideh, who has watched tenderly over me since Day 1.

To Seda Chavdarian and Vesna Rodic for molding me into the teacher that I am today.

To the faculty of the UC Berkeley French Department and the Romance Languages and

Literatures program for the opportunity for all of this. To Carol, for her unparalleled and

tireless advising and administration. To Lydia and Gail for their good governance. To

Professor Susan Maslan for offering me the chance to further my classroom experience.

To Jenelle, my graduate school partner in crime, seminars, mutual dread, and lazy

afternoons. I am forever sitting on your counter as you continue to your life and career.

To Liz Paris, for her transformative kindness, compassion and clarity at the eleventh

hour.

To my students over all my years of teaching. May you seek happy nights to happy days,

treasures. Especially to my Beano students in People’s Square. You made me human.

To David, for his persistence and compassion.

To the staff of the Hotsy Totsy Club, who watched over me and kept the light on: Aurora,

Cynthia, Eva, Karina, Nicole, Suki and Tabitha. To Jessica and Michael. To Richie. To

Jimmy. To all my Totsy family.

To Birthe, in the K-Fêt, abusing my trigramme.

To Matt and Matt, in The Graduate, over popcorn, on the third round. To Jonathan,

standing baffled by the window of a hostel in Lisbon. To Victoria, in the office, stalwart

and supportive.

To Emily, my always first robin of spring. To Brock, along the journey. To Jacob, Lauren

and Rupinder, in my living room, as I presided. To Alan, Amber, Alexis, Rachel Sarah

vi

and Thomas chatting away unsupervised in the Library of French Thought. To Gabriella,

the better of the two testaments to the potential of Sicilian-Genoan blends in our program.

To Oliver, the Occitan.

To Francis and to Jason, for sticking with me.

To Jim, for dinners and Sondheim.

To Dan, for your unending patience with me.

To Greg, of my heart, at Little Prague. To Maria, that summer that we shared one room

between us.

To Jake, with whom I bickered to my betterment.

To Chicle, el contencioso.

To Zane and Nick, on the patio, in the gloaming.

To Flor, my beloved petite sœur. To Léo, my fellow bon-vivant.

To Jess, who discovered me. To Audrey, who cared for me. To David, Ben and Steven

who taught me adventure. To Linda, who got us safely home. To Kiki, with our growing

pains, among the luxury stores.

To Jess, over guilt and Bloody Mary’s, disappointing ourselves but—strangely— never

Ayi. To Leslie, over the dining table, above the laptop screen, taming human nonsense,

rowdy interns and the English language.

To Emma, watching Gavin and Stacey, after massages.

To Iyonna, à Chatelêt la nuit, à Pho 14 l’après-midi.

To Scrap, in the car, approaching Del Mar.

To Irene, Jenna, Jill, Stacie and Kevin. From the patios of North County’s worthy public

schools to those of San Diego’s latest breweries. And now, those of your homes.

To the Dubinas: Hannah and Sarah. By your pool or among the Christmas cookies.

To Lauren, on any street between adventures, your iPhone C to light the way.

To McKenna, in any place I find you.

To Andrew and to James, standing before me, at your respective weddings.

vii

To my Aunts Frankie and Rosemary, and my grandmother Rose, who knew a lot about

love.

To my Aunt Paula and Teresa, who told me first about the world beyond my horizons.

To my mother, Christine, who worked many years and very hard for her children. To Jim,

for his calming presence and that beach in Hawaii.

To my father, Michael, who did not get to see this come to light. I know that you would

be proud. To my stepmother, Cynthia, for all her patience and toil by all our sides.

To my brother, Tim, for his love.

To Madame Girdner and to Madame Wight, who patiently outwaited my desire to test out

the imperfect subjunctive. To Rita and Terry Rowan, for their expansive love. To Dr.

Englund, whose research project proved very useful.

To Professors Julia Simon, Travis Bradley, Charles Oriel, Noah Guynn, Elizabeth

Constable, Robert Irwin and Adrienne Martín at UC Davis for being there for my wobbly

first steps into scholarship.

To Tricia, who loved me: I love you more.

To Corine and Marion. I cannot find the words, so you will have to keep listening to me

trying to find them for all our years to come. We will ever remain the upbeat clams!

To Orson, for showing us the bravery of growing up. To Cécile, who told me I should

need to live a long time. This dissertation has been Minute 1 of the many left to go.

To Eliot Leevit, who was much inconvenienced by all the fuss and ado I made as I wrote

this. But always loving.

To Maxime, concierge par excellence of the Hotel George V. Our brief, telephonic

exchange validated all my waking minutes of French study.

And, finally, to—

Oh! And to Great Grandpappy Arrigo, who [would have murdered] three men in Utah,

[would have bribed] the jury to get off and thereby beat the charges in 1915. In

retrospect, that was pretty key to all of this.

And, now, finally, to Little Michel and Amy, as they traipsed along the way to the East Davis

Dairy Queen. It was a clear day, and you did not think to look far. Certainly not as far as they

would one day find that I had gone. Pas mal, hein?

1

1 BACKGROUND AND REVIEW OF THE LITERATURE

1.1 Rumor and Romance: The Conditional for Unconfirmed Reports in the News

In the Romance speaking world, it is possible on any given day to open a newspaper and

find the conditional tense used as it is in the examples in (1-6):

(1) Spanish:

En cuanto al caso Lava Jato, según el periodista Fernando Rodrigues, habría no

menos de 57 personas vinculadas con el caso a las que se ha detectado alrededor

de 200 offshores previamente desconocidas.

‘With respect to the Lavo Jato case, according to the journalist Fernando

Rodrigues, there [would be] no less than 57 people connected to the case who

have been linked to some 200 previously unknown offshore companies.’

— El País, April 5, 2016

(2) Italian:

Secondo il quotidiano olandese «Trouw», infatti, Seedorf avrebbe concluso un

accordo di sponsorizzazione nel 2005 con un gioielliere italiano per la sua squadra

corse il «Team Seedorf Racing»

‘According to Dutch newspaper «Trouw», Seedorf [would have made] a

sponsorship agreement in 2005 with the Italian jeweler for his racing team «Team

Seedorf Racing»’

— Il Corriere della Sera, April 5, 2016

(3) Brazilian Portuguese:

Segundo os “Panama Papers” — o vazamento de 11,5 milhões de documentos

que implicam 140 personalidades que teriam offshores em paraísos fiscais —,

várias pessoas próximas a Putin teriam desviado quase dois bilhões de dólares

com a ajuda de bancos e empresas de fachada.

‘According to the “Panama Papers” — the leak of 11.5 million documents

implicating 140 people who [would have] offshore companies in tax havens —,

various people close to Putin [would have diverted] almost two billion dollars

with the help of banks and front companies.’

— O Globo, April 4, 2016

(4) Catalan:

Segons el diari, Crivillé hauria cobrat els drets d'imatge després del seu títol

mundial de 1999 a través d'una empresa 'offshore' situada en un paradís fiscal.

‘According to the newspaper, Crivillé [would have collected] the image royalties

from his 1999 world title through an offshore company located in a tax haven.’

— El Periódico de Catalunya, April 5, 2016

2

(5) Romanian:

Apropiați ai președintelui rus Vladimir Putin ar fi ascuns în paradisuri fiscale

aproximativ 2 miliarde de dolari prin intermediul unor societăți paravan deschise

de Mossack Fonseca.

‘Relatives of Russian President Vladimir Putin [would have hid] about $ 2

billion in tax havens through companies set up by Mossack Fonseca.’

— Adevărul.ro, April 5, 2016

(6) French:

C’est aussi le cas du meilleur ami du président, le violoncelliste Sergueï

Roldouquine, qui aurait servi de prête-nom pour le compte de M. Poutine pour

détourner de l’argent des entreprises publiques.

‘It is also the case for the president’s best friend, cellist Sergueï Roldouquine,

who [would have served] as the nominee for M. Putin’s account in order to

divert the money from state companies.’

—Le Monde, April 3, 2016

(1-6) are taken from around the time of the leak of documents revealing the international elite’s

extensive offshore holdings for purposes of tax evasion that has become known as the Panama

Papers. Although any of the conditionals used in (1-6) could be replaced by an appropriate

present or past indicative tense, the conditional is used to mark the fact that the newspaper is

hesitant to say that the information reported is certain. English journalists might mark such

information by adding the adverb allegedly in such cases, although it is not an exact equivalent.

The conditional has a pragmatic effect of signaling that the speaker (in these cases, journalist)

does not have direct knowledge of the information that they relay. This is reflected by the use of

the cognate prepositions según, secondo, segundo, segons (all meaning ‘according to’) in the

Spanish, Italian, Portuguese and Catalan examples in (1-4), thereby making the source of

information clear. However, the conditional may appear without a source. In the French and

Romanian examples in (5) and (6), the information is given without attribution. In French, this

use of the conditional has become so tightly associated with journalistic language that it has been

designated, among other things, the conditionnel de presse or press conditional.

1

Although the examples cited above suggest that the press conditional is a Pan-Romance

construction, its recognition and acceptance varies from language to language. Such is the

portrait painted by Squartini (2001) who compares the structure across Romance in a study that

includes French, Spanish, Portuguese, Italian and Catalan (but excludes Romanian). While

Squartini (2001: 324-26) only comments on the development of this use of the conditional in

Italian, the lack of comment about its origins in French and Portuguese leave one to assume it is

also native to those languages. Conversely, Squartini (2001: 318) describes the press conditional

in Spanish as an “unstable” French borrowing that is limited to journalistic language and unlikely

to be further integrated into the language. In fact, one of his sources, Romero Gualda (1994: 35-

36), suggests that the use of the press conditional in Spanish is in decline.

2

Squartini (2001: 320-

21) claims—on the basis of his sources—that Catalan also lacks a press conditional and suggests

that if it can be found, it is a French borrowing.

1

Dendale (1993: 165) provides a list of names. Several more have been added since.

2

This assertion is based on examples given by grammarians and an oral corpus from Fontanillo and Riesco (1994).

3

Subsequent research has painted a slightly different picture than the one depicted by

Squartini (2001). Martines (2015: 80-82) shows that this use of the conditional was present

historically in Catalan. Oliveira (2015a) has studied divergences with respect to the use of the

press conditional in European and Brazilian Portuguese. While one might speak of a “press

conditional” in Brazilian Portuguese (as one does in French), in European Portuguese, one would

need to speak of a “press future” as well as a “press conditional,” since both tenses are used to

convey uncertain information in journalistic texts. With regards to Spanish, the press conditional

has not proven “unstable” and has even received prescriptive sanction from the Real Academia

Española (RAE) in 2009 (RAE 2009: §23.15m). Kronning (2016: 128) finds that it is found

regularly in online news headlines in both Latin-America and Spain, although with greater

frequency in Latin-America. Furthermore, Romanists should not ignore a similar construction

found in Romanian. Popescu (2011: 234) notes that the press conditional is attested as early as

the 17

th

century and found in literary and scientific discourse as well as the oral code.

There does appear to exist a correlation between belief that the press conditional is a

native construction and its recognition by grammarians (and even linguists). Martines (2015: 81)

finds that although the press conditional appears to be native to Catalan, it has been condemned

in the language’s grammatical tradition as a French borrowing. In Spanish, the RAE’s (2009:

§23.15m) reference grammar does not describe the press conditional as a borrowing in origin,

but other grammars (such as Butt and Benjamin 1994: 220) as well as scholarly works continue

to describe it as a borrowing (Sarrazin 2010: 101). No one has yet carried out more extensive

diachronic work testing the contact hypothesis.

This alleged foreign origin has led to prescriptive discouragement of the press conditional

in Spanish, particularly in newspapers. El País, whose prestigious style guide has set the tone for

others across the Spanish-speaking world (Sarrazin 2010: 103), objects to the press conditional

on two grounds:

La posibilidad en el pasado no es, sin embargo, un hecho dudoso, no garantizado, ni un

rumor. Este uso del condicional de indicativo es francés…El uso del condicional en

ese tipo de frases queda terminantemente prohibido en el periódico. Además de

incorrecto gramaticalmente, resta credibilidad a la información (El País 2014:

§13.28). (bolding mine)

The fact that in Spanish the press conditional is considered an ungrammatical borrowing violates

what Cotter (2010: 136-37) calls the “rhetorical goals” of journalism. Journalists must use good

grammar in their writing to establish credibility (Cotter 2010: 191). The perception that the press

conditional would report unverified rumors further violates what Cotter (2010: 136-37) calls

journalism’s “content goals,” which insist on “accuracy.” However, the notion that the press

conditional might signify bad journalism is not restricted to Spanish. In French, the conditional is

acceptable but only within reason. Le Monde, France’s prestigious newspaper of record,

mentions the conditional specifically when laying out the newspaper’s commitment to accuracy:

Le Monde est précis. Les rédacteurs sourcent leurs informations. Ils utilisent les mots

justes, renoncent aux tournures vides et alambiquées. L’usage du conditionnel est

restreint. (Le Monde 2002: 48) (bolding mine)

4

In French, the conditional (whose status as a native form has never been in dispute) is acceptable

as long as it does not undermine the newspaper’s content goals. However, the construction itself

is not ungrammatical in French and its use does not violate the newspaper’s requirement for

good grammar.

3

Portuguese provides a useful point of comparison that helps explain why El País’s double

objection is remarkable. In Portuguese, the press conditional is also a point of concern as it may

undermine journalistic accuracy, as seen in the style guide of Portuguese newspaper Público:

Condicional — É um tempo verbal a usar com parcimónia, pois foge à precisão desejável

num texto jornalístico. Eis um mau exemplo: De acordo com uma informação divulgada

na Rádio Macau, teria sido o Governo de Lisboa que teria montado uma manobra de

informação para divulgar as acusações de que Carlos Melancia teria recebido 50 mil

contos. (...) [Carlos Melancia] negou a autenticidade da carta, cuja assinatura seria

falsa, e também que ela tivesse dado entrada (...).

4

(bolding mine)

As in French, the style guide of the Portuguese newspaper Público claims that the conditional

evades accuracy. It gives a “bad example” of the use of the conditional, wherein the construction

is used three times in one sentence. It appears that, like in French, the press conditional in

Portuguese may represent a content violation rather than a rhetorical violation. There is no

mention of the fact that the press conditional may be ungrammatical in Portuguese. It is clearly

the belief that the press conditional in Spanish is an ungrammatical foreign borrowing that

increases prescriptive pressure in that language relative to others.

In order to gain more insight into the press conditional, it is therefore necessary to

understand it doubly as a linguistic construction but also as a feature of a particular kind of

discourse whose particular aims condition its use. The Spanish case is especially compelling

because news discourse disfavors borrowing due to the importance it places on prescriptive

usage. In her work on borrowing through translation between English and French, McLaughlin

(2011) describes prescription in the journalistic context as a sufficient obstacle to borrowing:

If the nature and structure of the global news industry means that news translation has the

potential to be a cross-linguistic cause of change, it is also useful to consider what the

linguistic outcomes of such influence would be. The findings presented here indicate very

clearly that news translation is unlikely to lead directly either to global borrowing or to

selective borrowing of the formal type. This restriction can also be attributed to the nature

of the news industry in general because it results from the requirement that non-standard

usage be avoided (110).

McLaughlin (2011) cites Cotter’s (2010: 187) observation that news language tends to conform

to prescriptive guidelines, which may in many instances prevent borrowing from occurring in the

news genre. However, Cotter (2010: 211) also notes that prescription exists in tension with

3

Although the description used in French is précis, the best translation appears to be accuracy here, rather than

precision. In English, Cotter (2010: 137) distinguishes between both precision and accuracy: language is precise

while facts are accurate. However, she describes accuracy as a professional goal in journalism while precision is a

more general term. Furthermore, per Cotter (2010: 195), “precision safeguards accuracy.” The language in the Le

Monde regarding the word “précis” would appear to encompass both.

4

Publico, ed. 1998. “Verbos.” Público: Livro Do Estilo. 1998. http://static.publico.pt/nos/livro_estilo/index.html.

5

communicative need in news language, or what she calls a competition between the “prescriptive

imperative” and the “pragmatic alternative.” Prescriptive rules may sometimes be overridden to

suit the journalist’s needs. This would suggest that the press conditional has been—be it

borrowed or not—useful to Spanish-speaking journalists in practice.

For these reasons, the press conditional should prove ripe for a comparative investigation

between Spanish and French. Not only is French the potential donor of the press conditional in

Spanish, the recognition and acceptance of the press conditional in French is nearly the diametric

opposite of what is seen in Spanish. Furthermore, the study does not have to be limited to

linguistic comparisons (as in Kronning (2016), Vatrican (2010), Fouilloux (2006), Azzopardi

(2011)). Rather, I would argue it is worth investigating the press conditional from the perspective

of its press context in order to develop a deeper understanding of the construction as a linguistic

resource in journalism and how it violates (or does not violate) the journalistic ideal of accuracy.

Such an investigation should allow for an understanding of how the press conditional has proven

itself useful to Spanish journalism and give insight into the ways in which the press conditional’s

use diverges and converges across French and Spanish.

1.2 Form and Values of the Conditional in French and Spanish

The conditional forms of French and Spanish, as well as other Romance languages are

derived from a Latin verbal periphrasis combining an infinitive with the auxiliary verb HABERE

‘to have’ conjugated in the imperfect (Maiden 2011: 264-65). It was by this same process that

the Romance synthetic future forms were generated from HABERE conjugated in the present

tense (Maiden 2011: 264-65), which explains the formal similarity between the two tenses in

their eventual Romance outcomes. Maiden (2011: 265) illustrates this evolution using the verbs

VENIRE ‘to come’ and VALERE ‘to be worth,’ which yielded Fr. venir and valoir and Sp. venir

and valer. His examples are replicated in (7):

(7)

Spanish French

INF ualere ‘be worth’ > *vaˈlere valer valoir

FUT ualere + habet > *valeˈra valdrá vaudra

COND ualere + habebat > *valeˈreβa valdría vaudrait

INF uenire ‘to come’ > *veˈnire venir venir

FUT uenire + habet > *veniˈra vendrá viendra

COND uenire + habebat > *veniˈreβa vendría viendrait

Although it is not clearly illustrated by the verbs chosen by Maiden (2011), the infinitive form

often mirrors the future and conditional stem, and more often than not can be used to predict the

stem of the future and conditional tenses.

Although the tense is called the conditional, it was originally—and still is—a future-in-

the-past form. Its name derives from the fact that this new Romance form would eventually

largely supplant the Latin subjunctive in conditional phrases (Harris 1986).

5

At one point in time,

5

“The name ‘conditional’ is apt only insofar as it describes one common use of the form, viz. the expression of the

idea that an event is dependent on some other factor…” (Butt and Benjamin 1994: 219)

6

the conditional was so associated with its hypothetical uses that it was often classified as a

separate mood alongside the indicative and subjunctive. The classification appears incorrect, and

it is generally considered a tense with modal uses today (Vatrican 2014: 247). Abouda (1997)

provides a syntactic argument for the conditional’s categorization within the indicative paradigm,

on the basis that it is semantics and pragmatics, not syntax, that determine the use of the

conditional over other forms of the indicative. A choice between the conditional and another

indicative tense is, at its core, no different than the choice between a past and present tense.

Conversely, the subjunctive and indicative are not in syntactic free variation. Abouda (1997)

observes:

Or, comme l’on a vu tout au long de cet inventaire, nulle part le conditionnel n’est

syntaxiquement obligatoire ; il est simplement toujours possible. Sachant, d’autre part,

qu’il s’emploie dans les mêmes structures syntaxiques que l’indicatif, l’on dira que le

conditionnel n’est pas un mode : il s’agirait d’un temps de l’indicatif… (194).

Therefore, despite the conditional’s name and immediate associations, it is a tense like the future

or present tenses. The press conditional constitutes one of its modal uses.

1.2.1 The Forms of the Conditional in French and Spanish

In standard French and Spanish, the conditional tense has two forms: the present

conditional and the past conditional.

6

In each language, the past forms consist of a combination

of an auxiliary and past participle. The names conditionnel présent ‘present conditional’ and

conditionnel passé ‘past conditional’ are usual in French, while in Spanish, the present and past

conditional forms are often called the condicional simple ‘simple conditional’ and the

condicional compuesto ‘compound conditional.’ I will employ the terms present conditional and

past conditional as does Foullioux (2006) to refer to the two forms of the conditional in both

languages. I will introduce the forms of the French conditional in §1.2.1.1 and §1.2.1.2 and those

of Spanish in §1.2.1.3 and §1.2.1.4.

1.2.1.1 The Present Conditional in French

Morphologically, the present conditional in French is composed of three parts: a stem, the

morpheme –r-, and final person markers (Riegel, Pellat and Rioul 1994: 445). The stem of the

conditional is always the same as that of the future. The person markers are syncretic with those

of the imperfect indicative. Forms of the present conditional are shown in Table 1.1, using

regular verb parler ‘to speak’ and irregular verbs être ‘to be’ and avoir ‘to have’:

6

A third conditional form, constructed with two auxiliaries, is not unknown in French: il aurait eu chanté ‘he

[would have had sung]’. This conditional is called the conditionnel surcomposé and is one of the 7 double-

compound forms attested in the history of French. These forms are sufficiently infrequent that they might not be

recognized by speakers (Riegel, Pellat and Rioul 1994: 252).

7

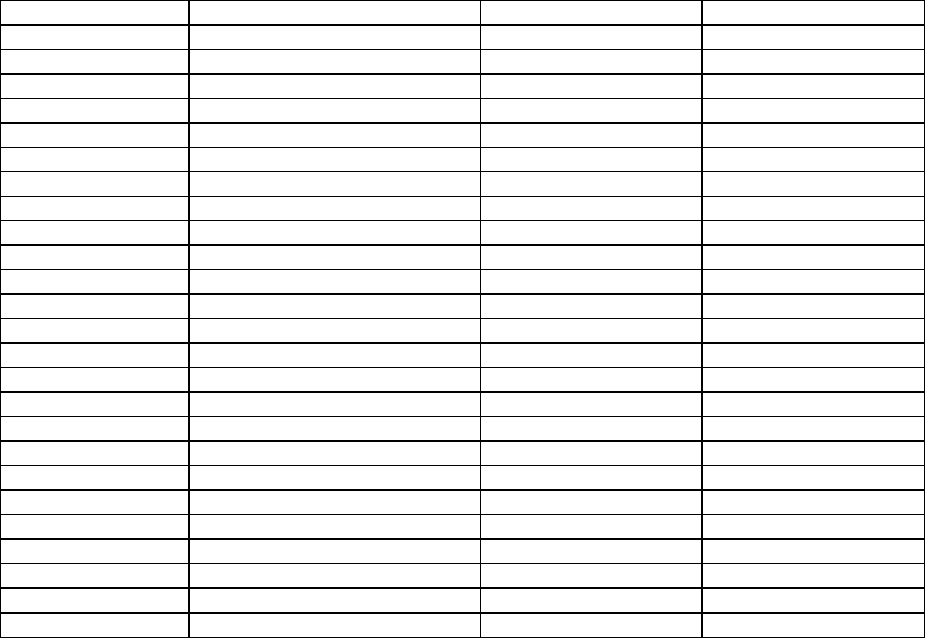

TABLE 1.1 FORMS OF THE FRENCH PRESENT CONDITIONAL

parler ‘to speak’

GRAPHIC

MORPHOLOGICAL

PHONOLOGICAL

ENGLISH GLOSS

je parlerais

je parle-r-ais

paʁ.ləˈʁɛ

‘I would speak’

tu parlerais

tu parle-r-ais

paʁ.ləˈʁɛ

‘You would speak’

on parlerait

on parle-r-ait

paʁ.ləˈʁɛ

‘One would speak’

nous parlerions

nous parle-r-ions

paʁ.ləˈʁjɔ

̃

‘We would speak’

vous parleriez

vous parle-r-iez

paʁ.ləˈʁje

‘You would speak’

ils parleraient

ils parle-r-aient

paʁ.ləˈʁɛ

‘They would speak’

avoir ‘to have’

GRAPHIC

MORPHOLOGICAL

PHONOLOGICAL

ENGLISH GLOSS

j’aurais

je au-r-ais

ɔˈʁɛ

‘I would have’

tu aurais

tu au-r-ais

ɔˈʁɛ

‘You would have’

on aurait

on au-r-ait

ɔˈʁɛ

‘One would have’

nous aurions

nous au-r-ions

ɔˈʁjɔ

̃

‘We would have’

vous auriez

vous au-r-iez

ɔˈʁje

‘You would have’

ils auraient

ils au-r-aient

ɔˈʁɛ

‘They would have’

être ‘to be’

GRAPHIC

MORPHOLOGICAL

PHONOLOGICAL

ENGLISH GLOSS

je serais

je se-r-ais

səˈʁɛ

‘I would be’

tu serais

tu se-r-ais

səˈʁɛ

‘You would be’

on serait

on se-r-ait

səˈʁɛ

‘One would be’

nous serions

nous se-r-ions

səˈʁjɔ

̃

‘We would be’

vous seriez

vous se-r-iez

səˈʁje

‘You would be’

ils seraient

ils se-r-aient

səˈʁɛ

‘They would be’

The regular verb parler ‘to speak’ in Table 1.1 illustrates the identical nature of the infinitive and

stem of the conditional. Irregular verbs avoir ‘to have’ and être ‘to be’ show conditional forms

with irregular stems, which in this case for être is ser– and for avoir is aur–. The person markers

are identical for all verbs.

1.2.1.2 The Past Conditional in French

The past conditional is one of the seven compound French tenses, consisting of one of the

auxiliary verbs avoir or être conjugated in the conditional (whose forms are outlined in Table

1.1) and a past participle. Per the rules of French auxiliary selection, avoir is used for most verbs,

while être is used obligatorily with all reflexive verbs and certain number of intransitive verbs. A

few intransitives may take either auxiliary (Riegel, Pellat and Rioul 1994: 252). These

possibilities are shown in (8), (9), (10) and (11):

(8) parler ‘to speak’ (avoir w/ transitives)

Vous auriez parlé

‘You would have spoken’

8

(9) se préparer ‘to prepare’ (aux. être w/ reflexives)

Vous vous seriez preparé(e)(s)

‘You would have prepared each other’

(10) arriver ‘to arrive’ (aux. être obligatory w/ certain intransitives)

Vous seriez arrivé(e)(s)

‘You would have arrived’

(11) disparaître ‘to disappear’ (avoir or être possible w/ certain intransitives)

Vous auriez disparu // Vous seriez disparu(e)(s)

‘You would have disappeared’

Since the French past participle must agree with a preceding direct object, all possible

combinations of gender and number agreement can be seen in (9), depending on whether vous

‘you’ is used in the singular or plural and to address a male or female addressee. When être is the

auxiliary agreement with the subject is obligatory as in (10) and in the alternate conjugation of

disparaître using être in (11).

1.2.1.3 The Present Conditional in Spanish

The Manual de la nueva gramática (RAE 2010: 50) describes the Spanish verb as

composed of four morphological segments: its root, its thematic vowel (-a-, -i-, -e- or Ø), a

temporal marker, and the appropriate person ending. The present conditional is marked by the

temporal marker –ría- (RAE 2010: 52). The conditional form of the regular verbs amar, partir,

temer and the irregular auxiliary verb haber, which loses its thematic vowel, are shown in Table

1.2:

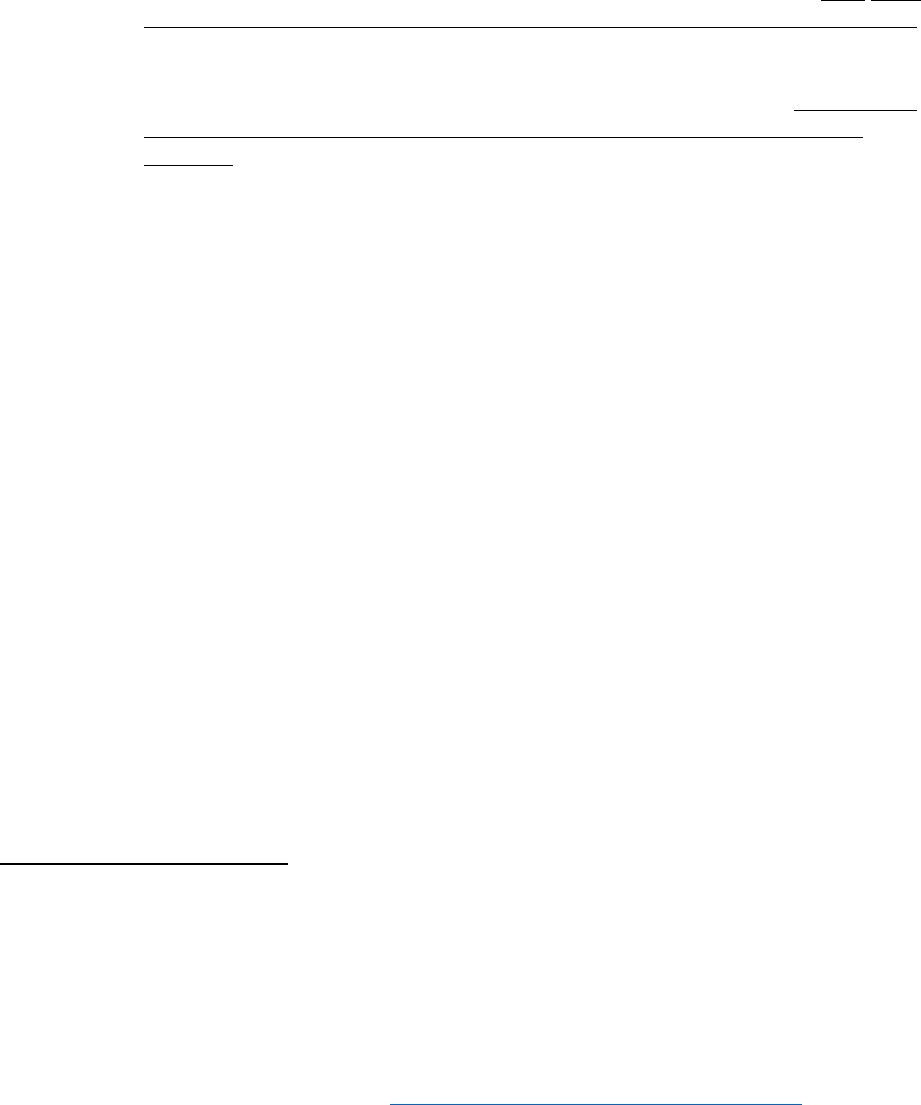

TABLE 1.2 FORMS OF THE FRENCH PRESENT CONDITIONAL

7

amar ‘to love’

GRAPHIC

MORPHOLOGICAL

PHONOLOGICAL

ENGLISH GLOSS

amaría

am-a-ría-Ø

a.maˈri.a

‘I would love’

amarías

am-a-ría-s

a.maˈrias

‘You would love’

amaría

am-a-ría-Ø

a.maˈria

‘S•he would love’

amaríamos

am-a-ría-mos

a.maˈriamos

‘We would love’

amaríais

am-a-ría-is

a.maˈri.ajs

‘You would love’

amarían

am-a-ría-n

a.maˈri.an

‘They would love’

salir ‘to leave’

GRAPHIC

MORPHOLOGICAL

PHONOLOGICAL

ENGLISH GLOSS

saldría

sald-Ø-ría-Ø

salˈdri.a

‘I would leave’

saldrías

sald-Ø-ría-s

salˈdri.as

‘You would leave’

saldría

sald-Ø-ría-Ø

salˈdri.a

‘S•he would leave’

saldríamos

sald-Ø-ría-mos

salˈdri.a.mos

‘We would leave’

saldríais

sald-Ø-ría-is

salˈdri.ajs

‘You would leave’

saldrían

sald-Ø-ría-n

salˈdri.an

‘They would leave’

7

The use of null morphemes has been controversial, but current consensus accepts their use (RAE 2010: 50).

9

TABLE 1.2: (continued)

hacer ‘to do’

GRAPHIC

MORPHOLOGICAL

PHONOLOGICAL

ENGLISH GLOSS

haría

ha-Ø-ría-Ø

aˈri.a

‘I would do’

harías

ha-Ø-ría-s

aˈri.as

‘You would do’

haría

ha-Ø-ría-Ø

aˈri.a

‘S•he would do’

haríamos

ha-Ø-ría-mos

aˈri.a.mos

‘We would do’

haríais

ha-Ø-ría-is

aˈri.ajs

‘You would do’

harían

ha-Ø-ría-n

aˈri.an

‘They would do’

haber ‘have’ - AUX

GRAPHIC

MORPHOLOGICAL

PHONOLOGICAL

ENGLISH GLOSS

habría

hab-Ø-ría-Ø

aˈbri.a

‘I would have…’

habrías

hab-Ø-ría-s

aˈbri.as

‘You would have…’

habría

hab-Ø-ría-Ø

aˈbri.a

‘S•he would have…’

habríamos

hab-Ø-ría-mos

aˈbri.a.mos

‘We would have…’

habríais

hab-Ø-ría-is

aˈbri.ajs

‘You would have…’

habrían

hab-Ø-ría-n

aˈbri.an

‘They would have…’

As in French, the infinitive is often a reliable guide to the formation of the conditional of regular

verbs in Spanish. Irregular verbs, as in the case of haber, may lose their thematic vowel (querer

‘to want’ > querría ‘I would want’). Some may lose the thematic vowel and undergo the

insertion of an epenthetic ‘d’ (salir > saldría) or have irregular stems (hacer ‘to do’> haría ‘I

would do’) (RAE 2010: 63).

1.2.1.4 The Past Conditional in Spanish

Unlike in French, which has maintained auxiliary selection between avoir ‘HAVE’ and

être ‘BE’ in its compound tenses, the Spanish past conditional is formed invariably by

combining the auxiliary haber ‘HAVE’ (whose forms are outline in Table 1.2) in the present

conditional with a past participle. The verbs amar, salir and hacer from Table 1.2 are illustrated

in (12), (13) and (14):

(12) amar ‘to love’

habrían amado

‘They would have loved’

(13) salir ‘to leave’

habrían salido

‘They would have loved’

(14) hacer ‘to do’

habrían hecho

‘They would have done’

The Spanish past participle remains invariable in Spanish, having lost the feature after the

medieval period (Arias and Quaglia 2002: 518).

10

1.2.2 Values of the Conditional in French and Spanish

Fouilloux (2006) undertakes a comparative study of the uses of the French and Spanish

conditional. She identifies four uses common to the two languages: the temporal conditional, the

hypothetical conditional, the attenuating conditional and the press conditional. She also notes

that Spanish has a conjectural use of the conditional that is not found in French and requires

translation by the French modal verb devoir ‘must’ (Fouilloux 2006: 65). In the latter case, the

conditional covers what Cornillie (2009: 50) labels as circumstantial inferentials or conjectures,

the latter involving some direct visual evidence and the former pure reasoning on the part of the

speaker. However, scholars have identified an inferential use of the French conditional found in

interrogative forms.

8

Furthermore, it appears that many descriptions of Spanish omit an

inferential use of the conditional that appears to be a feature of scientific texts and that differs

from the conjectural use routinely inventoried in reference grammars and the academic literature.

1.2.2.1 The Temporal Conditional in French and Spanish

The temporal conditional in French represents the use of the conditional to mark the

future-in-the-past, meaning that the event will take place in the future relative to a moment in the

past. Riegel, Pellat and Rioul (1994: 317) provide the examples seen in (15) and (16):

(15) Virginie pensait que Paul viendrait

‘Virginie thought that Paul would come’

(16) Elle affirmait qu’elle serait rentrée à midi.

‘She affirmed that she would have returned home at noon.’

The difference between the present and past conditional in the context of (15) and (16) is

aspectual. The action in (16) is seen as having been completed after the moment of elle affirmait

but before noon. In (15), Paul’s coming is in the future with respect to Virginie’s thoughts

concerning this event.

As in French, the conditional in Spanish also has a future-in-the-past function. Both the

present and past conditional have this function, as seen in (17) and (18):

(17) Me dijo que vendría

‘S•he told me that s•he would come’

(RAE 2010: 451)

(18) Afirmaron que cuando llegara el invierno habrían recogido la cosecha’

‘They affirmed that when winter came they would have gathered the harvest’

(RAE 2010: 453)

8

See Dendale (2010) for a thorough description.

11

As in French, there is an aspectual difference between the two conditional forms. The action in

(18) is viewed as completed by a certain reference point situated in the future, whereas the

example in (17) is simply said to occur at a time after the locutor produced the utterance.

1.2.2.2 The Hypothetical Conditional in French and Spanish

The conditional is used in French to represent the hypothetical result of a condition. This

is the usage from which the tense derives its name. Prototypical hypothetical utterances featuring

the conditional in French are marked by the word si ‘if’ in a subordinate clause and a present or

past conditional in the main clause as seen in (19). Other constructions also exist to mark the

necessary conditionals in such utterances, as in the example seen in (20), whose subordinate

clause begins with quand ‘when,’ which has a meaning akin to ‘even if’ in this context:

(19) Ah! Si vous vouliez devenir mon élève, je vous ferais arriver à tout

‘Ah! If you wanted to become my student, I would put all within your grasp.’

(Riegel, Pellat and Rioul 1994: 318)

(20) Quand tous mes rêves se seraient tournés en réalités, ils ne m’auraient pas suffi

j’aurais imaginé, rêvé, désiré encore

‘Even if all my dreams had come true, they would not have been enough: I would

have imagined, dreamed and desired still’

(Riegel, Pellat and Rioul 1994: 319)

Temporally speaking, the present conditional is used to make present or future hypotheses, while

the past conditional is used for hypotheses about the past. If the condition is set in the present or

future, the imperfect indicative is used after si as in vouliez in (19). If the condition is set in the

past, French uses the pluperfect indicative after si as in (20), which could be recast as si tous mes

rêves s’étaient tournés en réalités ‘if my dreams had come true.’ It is possible to replace the

pluperfect and past conditional forms of French si-phrases with the pluperfect subjunctive,

allowing for (20) to be reformulated as Si mes rêves se fussent tournés…, ils ne m’eussent pas

suffi…This is found, however, only in historical or formal—usually written—language (Riegel,

Pellat and Rioul 1994: 329).

In Spanish, the conditional is used after subordinate clauses introduced by si ‘if’ which

contain the imperfect or pluperfect subjunctive. Examples are shown in (21) and (22):

(21) Esto quiere decir que si usted realizase seis viajes con estas 15.000 ptas ahorraría

mas de 4.000 ptas

‘This means that if you made six journeys with these 15,000 ptas, you would save

more than 4,000 ptas’

(Butt and Benjamin 1994: 337)

(22) Si él hubiera tenido dinero, habría saldado la cuenta

‘If he had had money, he would have settled the bill’

(Butt and Benjamin 1994: 337)

12

As in French, the present conditional implies a present or future outcome if the condition were to

be met, as in (21), while the past conditional situates the outcome the past as in (22). In Spanish,

as in French, the pluperfect subjunctive in -ra may replace the past conditional in examples like

(22), yielding Si él hubiera/hubiese tenido, hubiera saldado la cuenta.

9

Unlike in French, such

usage is not confined to formal language (Butt and Benjamin 1994: 294). The two appear to be in

free variation (RAE 2010: 453).

1.2.2.3 The Attenuating Conditional in French and Spanish

The conditional can be used to soften a request in French. Examples can be seen in (23)

and (24):

(23) Je voudrais raconter le president

‘I would like to meet the president’

(Riegel, Pellat and Rioul 1994: 319)

(24) J’aurais voulu rencontrer le president

‘I would like to meet the president’

‘I [would like to have met] the president’

(Riegel, Pellat and Rioul 1994: 319)

Unlike the hypothetical and temporal conditionals, the example in (24) does not have a direct

translation in English and its linguistic gloss is in brackets. The only difference between (23) and

(24), other than their form, is their level of politeness. By rhetorically situating the request in the

‘past,’ the requester is creating further distance between them and the demand made, thereby

increasing politeness (Riegel, Pellat and Rioul 1994: 319).

The conditional is also used for courteous requests in Spanish. Examples are given in

(25) and (26):

(25) Convendría salir pronto.

‘It would be good to leave soon’

(RAE 2010: 452)

(26) Habría querido hablar con usted un momentito

‘I would like to speak with you for a moment’

‘I [would like to have spoken] with you for a moment’

(RAE 2010: 453)

9

The imperfect subjunctive, and, reflexively, the pluperfect subjunctive, have two forms in Spanish, one set ending

in -se descended from the Latin imperfect subjunctive and one set ending in -ra descended from the Latin pluperfect.

In cases where a proper subjunctive is called for, the two forms are interchangeable. Prescription holds that in “good

Spanish,” only the -ra form can replace indicative forms (i.e., the past conditional and—infrequently—the

pluperfect indicative) (Butt and Benjamin 1994: 294).

13

The RAE (2010: 453) notes that the example in (26) is more common in Latin-American Spanish

than in Spain and that (as in French) the use of the past conditional does not make for a temporal

difference in instances of request. Again, the effect is one of greater distance and politeness.

1.2.2.4 The Press Conditional in French

Riegel, Pellat and Rioul (1994: 320) call the press conditional le conditionnel de

l’information incertaine ‘the conditional of uncertain information’. It is used to report

information that is not verified or whose content the speaker cannot vouch for (Riegel, Pellat and

Rioul 1994:320). The present conditional can describe the present or future, while the past

conditional situates an event in the past (Riegel, Pellat and Rioul 1994: 320). Examples are given

in (27), (28) and (29):

(27) Une navette spatiale partirait bientôt pour Mars

‘[Allegedly] a space rocket will leave soon for Mars’

‘A space rocket [would leave] soon for Mars’

(Riegel, Pellat and Rioul 1994: 320)

(28) D’après un article qui vient de paraitre dans la revue “Postgraduate Medical

Journal” la nicotine serait le meilleur agent protecteur contre la colite

‘According to an article that recently appeared in the journal “Postgraduate

Medical Journal” nicotine is [allegedly] the best protective agent against colitis’

‘According to an article that recently appeared in the journal “Postgraduate

Medical Journal” nicotine [would be] the best protective agent against colitis’

(Haillet 2002: 81)

(29) Un chercheur français aurait découvert un traitement miracle du cancer

‘[Allegedly] a French researcher has discovered a miracle cure for cancer’

‘A French researcher [would have discovered] a miracle cure for cancer’

(Riegel, Pellat and Rioul 1994: 320)

This use of the conditional cannot be directly translated into English and requires some other

marker such as allegedy to approximate its pragmatic effect. Direct glosses are given in the

second gloss in (28) and (29). It also should be made clear that in French the present conditional

by default yields a present reading (i.e., is simultaneous to the moment of enunciation) and can

only refer to the future if a temporal marker is present (Fouilloux 2006: 73). The adverb bientôt

‘soon’ is, therefore, necessary to achieve the prospective reading of the example in (27).

1.2.2.5 The Press Conditional in Spanish

In Spanish, the press conditional is most frequently referred to as el condicional de rumor

‘the conditional of rumor.’ The RAE (2010: 450) treats it as a variant of the conjectural

conditional. The temporal extension of the present conditional form is greater than that seen in

French. In Spanish, the present conditional can refer to present or past states. The past

conditional refers to events in the past. Examples are given in (30), (31) and (32):

14

(30) La nota daba a entender que el presidente estaría dispuesto a negociar

‘The note led one to understand that the president [allegedly] was open to

negotiating’

‘The note implied that the president [would be] open to negotiating’

(RAE 2010: 450)

(31) La desaparición de los etarras estaría motivada por cuestiones de seguridad

‘The disappearance of the ETA members is [allegedly] motivated for reasons of

security’

‘The disappearance of the ETA members [would be] motivated for reasons of

security’

(Butt and Benjamin 1994: 220)

(32) Un periódico daba cuenta ayer de una operación en la que habrían muerto

‘A newspaper was reporting on an operation in which they [allegedly] died’

‘A newspaper was reporting on an operation in which they [would have died]’

(RAE 2010: 453)

The use of the present conditional to refer to the past is not possible in French (Gosselin 2001:

62-63). However, in Brazilian Portuguese, the present conditional can be used with a temporality

like that of the imperfect (Oliveira 2015a: 216). This shows that instances where the Spanish

press conditional differs from French are not necessarily exceptional, at least in this instance.

The present conditional in Spanish may refer to future events whether accompanied by a

temporal marker or not, a potential instance of innovation first noted by Sarrazin (2010).

Examples are given in (33) and (34):

(33) Según la agencia EFE, el presidente saldría mañana para Londres

‘According to the EFE news agency, the president [allegedly] will leave

tomorrow for London’

‘According to news agency EFE, the president [would leave] tomorrow

for London’

(Sarrazin 2010: 109)

(34) Villa Parque San Miguel sería parte del ejido municipal de Carlos Paz

‘Villa Parque San Miguel [allegedly] will be part of the municipal lands of

Carlos Paz’

‘Villa Parque San Miguel [would be] part of the municipal lands of

Carlos Paz’

(Sarrazin 2010: 110)

If the Spanish press conditional is indeed a calque from French, then the example in (34)

represents an innovation that has occurred within Spanish, as a future time marker would be

required for the conditional to be used this way in French. While (33) could be translated directly

by sortirait demain ‘would leave tomorrow’ due to the presence of future time marker, (34)

15

requires a formulation such as pourrait faire partie ‘could be part’ or devrait faire partie ‘should

be part’ (Sarrazin 2010: 110).

1.2.2.6 Inferential Uses of the Conditional in French

The inferential uses of the conditional in French and Spanish merit separate discussions

due to their more extensive differences. French is often thought not to have a conjectural use of

the conditional, but one has been identified by Tasmowski (2001).

10

However, this use of the

conditional occurs only in the interrogative, while the press conditional is found only in

assertions (Dendale and Bourova 2013: 188; Rossari 2009: 77). Examples of this conjectural use

of the conditional in French are provided in (35) and (36):

(35) Ta femme serait-elle absente?

‘Is your wife gone?’

‘[Would] your wife [be] gone?’

(Dendale 2010: 299)

(36) Aurait-il oublié le rendez-vous?

‘Did he forget the appointment?’

‘[Would] he [have forgotten] the appointment?’

(Dendale 2010: 299)

In both (35) and (36), an answer is not sought by the speaker. Dendale (2010: 299) notes that in

each case, if one did respond to the question, an appropriate response would be something like

c’est possible ‘it’s possible’ rather than oui ‘yes’ or non ‘no.’ Dendale (2010: 296) describes the

hypotheses presented in this conditional as derived through inference.

As was said above, it is not thought that an inference can be marked by the conditional in

an assertion in French. However, Guentchéva (1994: 17-18) raises the possibility. She provides

the example seen in (37):

(37) Les résultats des examens réalisés, notamment à l'hôpital neuro-cardiologique de

Lyon, par le docteur T., neuro-cardiologue, et par le professeur V., toxicologue,

font état de la présence dans le sang, où le taux d'alcoolémie atteignait 1,8

gramme, d'opiacés, de la morphine en particulier. La cause de la mort serait ainsi

une crise cardiaque déclenchée dans un contexte de prise d'opiacés par voie

buccale qui ne semble pas devoir être assimilée à une « surdose ». Ces

constatations des experts donnent heure à l'ouverture d'une instruction pour

infraction à la législation sur les stupéfiants qui va tenter de retrouver le

fournisseur d'éventuels produits prohibés.

‘The results of the examinations carried out, notably at the neuro-cardiological

hospital of Lyons, by Doctor T., neuro-cardiologist, et by Professor V.,

toxicologist, confirms the presence of opiates, [and] of morphine in particular in

the blood, where the rate of blood alcohol reaches 1.8 grams. The cause of death

[would be] therefore a heart attack triggered in the context of oral opioid

10

Previously, scholars had treated it as equivalent to the press conditional (Dendale and Bourova 2013: 186-88).

16

consumption which appears not to necessarily reach the level of an “overdose.”

These expert findings provide the justification for the opening of an investigation

for violation of the law regarding narcotics which will attempt to find the ultimate

provider of banned substances.’

If this conditional is indeed inferential in nature, it is the journalist who is drawing a connection

between the toxicology report and earlier reports that the man had died of a heart attack.

1.2.2.7 Inferential Uses of the Conditional in Spanish

The Spanish conditional can mark inferences in two ways. The first is routinely described

in grammars and is known as el condicional de conjetura ‘the conjectural conditional.’ This use

of the conditional marks inferences about the past. In such cases, the present conditional can be

glossed by imperfect indicative and the past conditional by the pluperfect indicative and an

adverb like probablemente ‘probably’ (RAE 2010: 450). Examples are given in (38) and (39):

(38) Serían las diez

‘It was probably 10 o’clock’

‘It [would be] 10 o’clock’

(RAE 2010: 450)

(39) Ojalá Lucrecia no fallara al otro día, pensó, habría tenido algún contratiempo

‘If only Lucrecia had come through the other day, she must have had some

mishap’

‘If only Lucrecia had come through the other day, she [would have had] some

mishap’

(RAE 2010: 453)

As is seen in (38), the present conditional refers to a moment prior to the moment of enunciation,

while in (39) the conditional refers to a past action prior to another moment in the past.

The second inferential use of the conditional in Spanish can be found in scientific articles

wherein the conditional reflects inferences based on evidence and reasoning. Examples of this

use of the conditional can be seen in (40), (41) and (42):

(40) Como los dientes aquí descriptos no presentan diferencias morfológicas

significativas con los dientes del Aucasaurus, esto sugeriría que los restos de

titanosaurios podrían haber sufrido alguna forma de acción atrófica por parte de

un terópodo abelisaurio u otro terópodo con una morfología dental convergente

con estos.

‘As the teeth here described do not present any significant morphological

differences with the teeth of Aucasaurus, this [would suggest] that the remains of

the titanosaurus [could have suffered] some form of atrophic action on the part

of the abelisaur therapod or another therapod with a dental morphology

convergent with those.’

(Ferrari 2009: 13)

17

(41) Por otro lado, se observa una escasa participación de los trabajadores informáticos

en redes virtuales e institucionales, siendo que este tipo de vinculaciones podría

generar competencias que complementaran las calificaciones obtenidas en el

sistema de educación formal.

‘On the other hand, one observes a low participation of software workers in