Drugs, Substance Abuse,

and Public Schools

A Legal Guide for School Leaders Amidst Evolving Social Norms

With a foreword by the National Association of School Nurses

Drugs, Substance Abuse,

and Public Schools

A Legal Guide for School Leaders Amidst Evolving Social Norms

With a foreword by the National Association of School Nurses

Copyright © 2019 by the National School Boards Association. All Rights Reserved.

DRUGS, SUBSTANCE ABUSE, AND PUBLIC SCHOOLS

1

TABLE OF CONTENTS

FOREWORD ....................................................................................................................................................... 4

INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................................................................5

I. MEDICATIONS AT SCHOOL .........................................................................................................................6

Q1. What policies and procedures are needed to ensure that all student medications at school are properly

stored and administered? .................................................................................................................................... 6

Q2. Who can administer medications to students at school? Under what circumstances may unlicensed

assistive personnel (UAP) do so? .........................................................................................................................7

Q3. Should schools include the administration of medication in a student’s IEP or Section 504 plan? .......... 8

Q4. Should school districts allow parents/guardians to volunteer to administer medications to their

children? Does it matter whether the parent is a licensed medical professional? What policies and

procedures should be in place if the district determines that parent volunteers may administer medication

to their own or other children (such as on eld trips)? ...................................................................................... 9

Q5. Who should administer medication in school if trained medical sta are not available? .......................... 9

Q6. Are there any legal protections for school nurses, other sta, or the district for administering

medications to students? ...................................................................................................................................10

Q7. Given that the FDA classies naloxone as a prescription-only drug, should school districts have a

supply of naloxone available to administer to individuals who have overdosed? What state level naloxone

administration laws include schools as a site for having naloxone on hand? .................................................. 11

Q8. Should school districts have certain common emergency medications on hand beyond student-specic

prescriptions taken in accordance with an individualized healthcare plan, Section 504 plan, or IEP? ........... 11

Q9. When certain drugs (e.g., epinephrine autoinjectors) necessary to student care are unavailable (e.g.,

due to shortages or exorbitant costs), what alternatives does a district have?

Is it acceptable to administer

expired drugs? What protocols should be in place? ..........................................................................................12

II. MARIJUANA ................................................................................................................................................ 13

Q10. If a student is prescribed or is a registered user of medical marijuana, must a school district permit

the use of the drug on school premises or provide other accommodations for the individual’s use of

medical marijuana? .......................................................................................................................................13

DRUGS, SUBSTANCE ABUSE, AND PUBLIC SCHOOLS

2

Q11. May a school allow a student to use medical marijuana on school grounds without violating federal law?

How does this aect any federal funds the district may receive? ....................................................................14

Q12. If a school decides to permit student use of medical marijuana, who should administer it?

Where

should it be stored? .............................................................................................................................................14

Q13. What steps should school districts take to verify that a student is a registered user of medical

marijuana and that the person administering it is legally permitted to do so? ................................................14

Q14. Can a school prohibit students from possessing, using, or distributing medical marijuana at school?......15

Q15. Can a school district regulate a student’s legal use of marijuana (whether medical or recreational)

o-campus?.........................................................................................................................................................15

III. TOBACCO AND RELATED PRODUCTS ......................................................................................................16

Q16. May schools prohibit the possession and use of tobacco products at school by students? ...................16

Q17. May schools prohibit vaping devices, such as e-cigarettes? .....................................................................16

Q18. Is vaping an acceptable method of administering medical marijuana? ...................................................18

IV. SCHOOL AUTHORITY TO DISCIPLINE AND STUDENT RIGHTS .............................................................18

Q19. What student rights should schools keep in mind when developing policy and making decisions

regarding student discipline for drug involvement? .......................................................................................... 18

Q20. May a school district discipline a student for being under the inuence of a drug or alcohol while at

school? May a school district require an impairment assessment onsite if a student is suspected of being

under the inuence of drugs or alcohol? .......................................................................................................... 20

Q21. When can a school district require a student to submit to drug or alcohol testing? .............................. 20

Q22. Can a school district require a student to undergo/continue participating in drug/alcohol treatment

as a condition of attending school or participating in extracurricular activities? ........................................... 20

Q23. Can a school district prohibit a student found to have committed a drug/alcohol infraction, whether

on or o campus, from participating in extracurricular activities? ................................................................. 20

Q24. What special rules apply to the discipline of IDEA-covered students who are alleged to have violated

the district’s drug policies or federal/state law? ...............................................................................................21

Q25. Does student alcoholism or illicit substance use or chemical dependency qualify as a disability under

the IDEA or Section 504? If so, does this change how a district may discipline a student found to have

committed a drug or alcohol infraction? ........................................................................................................... 22

DRUGS, SUBSTANCE ABUSE, AND PUBLIC SCHOOLS

3

Q26. What considerations should a school district address in its code of conduct provisions concerning

student involvement with illicit substances? .................................................................................................... 22

V. STUDENT EDUCATIONAL PERFORMANCE AND DRUG USE .................................................................. 23

Q27. If school leaders suspect that a student’s educational performance is aected by his/her established

or suspected chemical dependence, what are the school district’s responsibilities toward that student? ....... 23

Q28. Should school districts address a special education student’s chemical dependency in his/her IEP? .... 23

Q29. May a school district delay an educational evaluation of a student it suspects is actively

using chemicals? ................................................................................................................................................ 23

Q30. Can a school district require a student to undergo a chemical health assessment as part of an

educational evaluation? ..................................................................................................................................... 24

VI. STUDENT PRIVACY AND DRUG USE ........................................................................................................ 24

Q31. What does federal law require schools to do to keep student medication and drug involvement

information condential? .................................................................................................................................. 24

Q32. How do applicable laws address continuity of care communications between healthcare providers

and school nurses when a student returns to school from inpatient drug use treatment? ........................... 24

RESOURCES .................................................................................................................................................... 25

CHARTS ........................................................................................................................................................... 26

ENDNOTES ......................................................................................................................................................40

NSBA thanks the National Association of School Nurses for reviewing and providing input to this publication.

DRUGS, SUBSTANCE ABUSE, AND PUBLIC SCHOOLS

4

FOREWORD

A third grade student comes to school days after being diagnosed with type 1 diabetes,

requiring insulin and treatment in case of low blood glucose. An assistant principal nds a

ninth grade student hidden behind a car vaping in the high school parking lot. School district

leaders attend a community conversation hosted by the state health department – the topic

of discussion: the opioid epidemic. These reality-based scenarios require school board

guidance and policy development. School nurses and other local school professionals implement school board

policies to support student health, safety, and readiness to learn.

As a partner in support of student success and well-being, the National Association of School Nurses (NASN)

worked closely with the National School Boards Association (NSBA). NASN members possess expertise to

inform evidence-based policies and practices for safe medication administration in schools. We are pleased

to collaborate with NSBA in the review of this legal guide for school leaders. School nurses observe the home

and community factors that impact student health and learning and work with the school team and link with

community-based resources to support students. These data are shared with school boards to inform their

policy making. Topics such as medical marijuana use in schools and drug use by students require knowledge of

federal and state laws. This legal guide provides responses to the questions school leaders are asking, making

the guide useful and practical for school boards. NASN applauds NSBA for gathering and organizing current

state laws on drugs and substance use as they relate to schools.

Drugs, Substance Abuse and Public Schools: A Legal Guide for School Leaders Amidst Changing Social Norms,

reects the NSBA’s mission to advocate for equity and excellence in public education through school board

governance and NASN’s mission to optimize health and learning for all students by advancing school nursing

practice. School boards will nd the information needed to write policies and implement practices that support

healthy, safe, and supported students.

Donna Mazyck

Executive Director

National Association of School Nurses

DRUGS, SUBSTANCE ABUSE, AND PUBLIC SCHOOLS

5

INTRODUCTION

Today more than ever issues of drugs and medications in schools present a challenging

landscape for school boards and school ocials. This legal guide is intended to help

schools navigate the complicated patchwork of federal, state and local laws and

regulations governing the presence and use of both authorized medications and illicit

drugs in school. From medication management to increasingly novel issues such as

medical marijuana, to the rise of troubling trends aecting children such as the opioid addiction and

e-cigarettes, to student privacy rights and discipline, this publication will guide school board members in

policy making and school board ocials in identifying issues and appropriate responses to help ensure

student well being and to maintain safe school environments. The National School Boards Association is

especially pleased to be joined by the National Association of School Nurses in this eort, and we

acknowledge their generous review. Our hope is that this guide, which will live digitally on the NSBA website

and will be available through many of our state association members, will help school leaders proactively

prepare for and meet the many challenges, new and old, in this area.

Thomas J. Gentzel

Executive Director & CEO

National School Boards Association

DRUGS, SUBSTANCE ABUSE, AND PUBLIC SCHOOLS

6

I. MEDICATIONS AT SCHOOL

Q1. What policies and procedures are needed to ensure that all student medications at

school are properly stored and administered?

Some states have laws or standards that establish specic policies for administration of medications in

schools that apply to all school districts in that state.

1

This prevents signicant discrepancies between school

districts within the state and reduces confusion for parents of medicated children and prescribing health care

professionals. When state laws or guidelines do not exist, school health professionals, consulting physicians,

and medical advisory committees should be involved in this process.

2

Well-written policies and procedures will enable schools to fulfill their obligations to provide needed

health-related services to students during the school day with consistency. School policies and

procedures should address:

• delegation (when permissible by state law), training, and supervision of unlicensed assistive

personnel (UAP);

• student condentiality;

• medication orders;

• medication doses that exceed manufacturer’s guidelines;

• proper labeling, storage, disposal, and transportation of medication to and from school;

• documentation of medication administration;

• rescue and emergency medications;

• o-label medications and investigational drugs;

• prescription and over-the-counter (OTC) medications;

• complementary and alternative medications; and

• psychotropic medications and controlled substances.

3

DRUGS, SUBSTANCE ABUSE, AND PUBLIC SCHOOLS

7

Q2. Who can administer medications to students at school? Under what circumstances may

unlicensed assistive personnel (UAP) do so?

Ideally, registered professional school nurses should be responsible for administering medication in the school

setting. To administer any prescribed medication, schools should require a written statement from the parent

and the physician that provides the name of the drug, the dose, approximate time it is to be taken, and the

diagnosis or reason the medication is needed.

7

Individualized Healthcare Plans

What – An Individualized Healthcare Plan (IHP) is a written document that describes the medical needs

of a student during the school day and outlines how the school will provide healthcare services to the

student, along with specic student outcome goals.

Why – IHPs are created for students whose healthcare needs aect or have the potential to aect their

safe and optimal school attendance and academic performance.

4

IHPs fulll administrative and clinical

purposes including management of healthcare conditions to promote learning; facilitating communication,

coordination, and continuity of care among service providers; and evaluation/revision of care provided.

5

How – IHPs are typically developed using steps based on the nursing process:

1. Assessment: The school nurse collects comprehensive data pertinent to the student’s health

and/or situation.

2. Nursing Diagnosis: The school nurse analyzes the assessment data to determine the diagnoses

or issues.

3. Outcome Identication: The school nurse identies expected outcomes for a plan individualized

to the student or the situation.

4. Planning: The school nurse develops a plan that prescribes strategies and alternatives to attain

expected outcomes.

5. Implementation: The school nurse implements the identied plan.

6. Evaluation: The school nurse evaluates progress toward attainment of outcomes.

6

Whom – The IHP usually is developed and managed by the school nurse, in collaboration with the

student, family, and healthcare providers.

When – Usually the school nurse implements, manages, and evaluates the IHP at least yearly and as

changes in a student’s health status occur to determine the need for revision and evidence of desired

student outcomes.

DRUGS, SUBSTANCE ABUSE, AND PUBLIC SCHOOLS

8

When a school nurse is not available, it is recommended that a trained and supervised unlicensed assistive

personnel (UAP) who has the required knowledge, skills, and composure to deliver specic school health

services do so, under the guidance of a licensed Registered Nurse (RN). A licensed RN, or a school nurse,

may delegate duties that allow UAPs to provide standardized routine health services. UAPs operate under the

supervision of the nurse, and on the basis of physician guidance and a school nursing assessment of the unique

needs of the student and the suitability of delegation of specic nursing tasks.

8

The nurse determines which nursing services can be delegated and then selects, trains, and evaluates the

performance of a UAP (within the personnel policies of the school district), audits school medication records

and documents, and conducts refresher classes throughout the school year.

9

The training, certication,

and supervision of a UAP should be determined by national and state nursing organizations and state nurse

practice laws. In most circumstances, a medication UAP should be an ancillary health oce sta member

(health assistant/aide) who is also trained in basic rst aid and district health oce procedures.

10

The administration of certain medications may be specically designated by law as a “nursing function” that

may not be delegated to a UAP, such as those that are required to be given intravenously or subcutaneously,

or those that need to be specically measured, or for which the dosage must be based upon the symptoms in

question.

11

Most states now expressly permit non-medical personnel to administer some emergency injectable

medications, such as EpiPens for allergies and glucagon for diabetes.

12

Other medications, such as those that

must be rectally administered in emergency situations, like the commonly prescribed emergency medication

for epilepsy called Diastat, vary more widely state by state.

13

In some instances, older and responsible students should be allowed to self-medicate at school with over-

the-counter medications and certain prescription medications (albuterol for asthma, insulin for diabetes)

when this is recommended by the parent and physician.

14

Schools should obtain written notication from

parents acknowledging that the school bears no responsibility for ensuring the medication is taken. School

districts allowing such self-medication often establish clear policy stating that if a student shares his/her

medication with classmates, the school will immediately conscate the medication and revoke the student’s

privilege of self-administration.

Q3. Should schools include the administration of a medication in student’s IEP or Section

504 plan?

Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act

15

and the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA)

16

provide

protection for students with disabilities by requiring schools to make reasonable accommodations, to provide

special education and related services, and to allow for safe inclusion of these students in school programs.

These federal laws do not cover all students who require medications during the school day (e.g., short-term),

and are not specic about how administration of medications should be conducted in school.

17

If a student with a qualifying disability under the IDEA and/or Section 504 requires the administration of

medication during the school day, such administration is typically deemed to be a related service to which the

student is entitled as part of his accommodations and/or special education services under these statutes.

18

DRUGS, SUBSTANCE ABUSE, AND PUBLIC SCHOOLS

9

Under Section 504, in addition to the development of an IHP, parents and the student are entitled to an

evaluation and meetings using a team process that involves the parents to determine what accommodations

are necessary and/or appropriate for the student.

19

A similar process takes place under IDEA as a student’s

Individualized Education Program (IEP) is developed and modied.

Q4. Should school districts allow parents/guardians to volunteer to administer medications

to their children? Does it matter whether the parent is a licensed medical professional? What

policies and procedures should be in place if the district determines that parent volunteers

may administer medication to their own or other children (such as on eld trips)?

Maybe. Some parents who are accustomed to providing medication and other services to their children may

volunteer to do so on eld trips and at school events. Even when state law does not prohibit this practice,

schools should ensure that the parents are aware that while the school may allow parents to provide such

services to their students, they are not required to do so.

20

Without proper documentation of the fact that the

parents have requested to provide these services, it may appear that the school is unwilling or ill-equipped

to provide them.

21

Schools should document in a student’s Section 504 plan the procedures to be followed

when a parent provides certain accommodations, and should state clearly that the school is able and willing to

provide the services if the parents is unwilling or unable to do so. In many cases, it is helpful (and in some cases

necessary) to set forth protocols for parents who voluntarily choose to provide services for their child on a

regular basis to notify the school when they are not able to do so for a specic event.

22

In some cases, there may be a parent with current nursing qualications who volunteers to serve in his/her

nursing capacity on school trips or at school events. Schools should be cautious about how they handle these

arrangements, as the volunteer nurses would be providing professional services, not just general volunteer

services. Schools should review their insurance policies and contact their carriers, where necessary, to determine

whether a volunteer nurse would be covered under the school’s liability coverage. While schools should check with

their carriers to be sure, it is likely that coverage eectively will extend to the volunteering parent. If the school

determines that it is necessary or benecial to hire the individual on a per diem basis, it also should make sure

that such action is not in violation of any bidding requirements or other legal obligations.

Q5. Who should administer medication in school if trained medical sta are not available?

On rare occasions when a member of the health oce sta (RN, licensed practice nurse, or UAP health

assistant/aide) is not available, other willing volunteer school sta may be trained by the licensed RN to

assume specic limited tasks such as single dose medication delivery or lifesaving emergency medication

administration.

23

In those instances, it is important for the school district to identify and satisfactorily address

medical liability issues for the district, the nurse, and the voluntary nonmedical sta member who is serving

temporarily as UAP.

DRUGS, SUBSTANCE ABUSE, AND PUBLIC SCHOOLS

10

Q6. Are there any legal protections for school nurses, other sta, or the district for

administering medications to students?

State laws provide tort immunity for school ocials, including school nurses, though that immunity varies

by state. Federal courts have recognized that federal, state, and local ocials, including school ocials, are

entitled to qualied – not absolute — immunity when they are sued for damages in cases claiming violations of

the Constitution and federal law.

24

The Supreme Court has not denitively decided if qualied immunity shields

school nurses regarding violations of administering mediations, though some federal courts have extended the

right to school nurses in the Fourth Amendment (search/seizure) context.

25

School districts should seek legal advice when they assume the responsibility for giving medication during

school hours. Liability coverage should be provided for the sta, including nurses, teachers, athletic sta,

principals, superintendents, and school board members.

26

Schools should establish protocols for the documentation of all medications given at school, whether emergency

or routine. Some schools use a log; others use a computer-based student medical record system. Any errors

The Opioid Crisis

Every day, more than 115 people in the U.S. die after overdosing on opioids.

28

Unintentional drug

overdose is one of the leading causes of preventable death in the country.

29

According to the Centers

for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), the rate of overdose among high school students nearly

doubled from 1999 to 2015.

30

From 2014 to 2015, overdose deaths increased by 19% among high school

aged children (15-19).

31

A study conducted to estimate risk of future opioid misuse among high school

adolescents found that legitimate opiate use in the high school years (to manage pain) is “independently

associated with a 33% increase in the risk of future opioid misuse after high school.”

32

Naloxone is a medication designed to rapidly reverse opioid overdose. It is an opioid antagonist—it binds

to opioid receptors and can reverse and block the eects of other opioids. It can very quickly restore

normal respiration to a person whose breathing has slowed or stopped as a result of overdosing with

heroin or prescription opioid pain medications. There are three FDA-approved formulations of naloxone:

1) injectable (professional training required); 2) autoinjectable; and 3) prepackaged nasal spray.

33

Some states have increased access to naloxone by passing legislation protecting prescribers and

dispensers. Currently, 35 states give immunity to third-party prescribers and those who dispense

naloxone to an overdose victim. A third-party prescriber is a pharmacist who prescribes a drug to a

person other than for whom the drug is intended. Here, naloxone is made available to people who are

likely to be near a person who is overdosing, often users themselves or concerned family members.

In a school setting, the third party could be a school nurse or member of the school’s administration.

Currently, 46 states permit pharmacists to prescribe naloxone to third parties, while ve continue to

prohibit the practice.

34

DRUGS, SUBSTANCE ABUSE, AND PUBLIC SCHOOLS

11

in medication administration at school need to be reported to at least one common supervisor so that patterns

of errors can be identied, and corrective action can be taken. Measures taken by school administrators after a

medication error must be designed so that they do not discourage sta self-reporting of errors.

27

Q7.

Given that the FDA classies naloxone as a prescription-only drug, should school districts

have a supply of naloxone available to administer to individuals who have overdosed? What

state level naloxone administration laws include schools as a site for having naloxone on hand?

Maybe. The pharmaceutical company that makes Narcan (currently the only available FDA-approved nasal spray

version of naloxone) oers limited free doses to libraries, YMCAs, and high schools in the U.S.

35

In the school

setting, school nurses are the most likely to administer naloxone to an overdosing student, but other personnel

may be on the scene rst.

36

Some school districts have hesitated to participate in this program, asserting that the risk of liability is greater

than the potential benet. Others, alternatively, note “the severity of the opioid problem has overwhelmed any

concerns they might have about the optics of naloxone.”

37

Many states have Good Samaritan laws that protect bystanders and rst responders who help in an emergency;

these laws usually apply in the school setting. Depending on the state, school personnel are immune from civil and/

or criminal liability when they assist in an overdose emergency at school. When a naloxone dispenser acts within the

scope of her employment and administers naloxone to an overdose victim at school, the law usually presumes that

the person is acting in the state’s interests by preventing an overdose. She is usually protected not only by newer

naloxone legislation, but also by her state’s tort immunity laws, and the extension of Good Samaritan laws.

38

Q8. Should school districts have certain common emergency medications on hand beyond

student-specic prescriptions taken in accordance with an individualized healthcare plan,

504 plan or IEP?

Yes. For lifesaving emergency medications to be eective, they must be accessible immediately in emergency

situations. Schools should make the availability of such medications (e.g., autoinjectable epinephrine, albuterol,

rectal diazepam, and glucagon) a high priority. To maintain medication security and safety and to provide for timely

treatment, school procedures should specify where medications will be stored, who is responsible for the medication,

who will regularly review and replace outdated medication, and who will carry the medication for eld trips.

Emergency Plans

Stocking emergency medications is a solid practice, but not a substitute for emergency action plans that

call for notifying rst responders. School districts should develop clear emergency action policies and

procedures, and actively train sta to follow them. Sta should call 911 in a medical emergency, including

one requiring the administration of emergency medication.

DRUGS, SUBSTANCE ABUSE, AND PUBLIC SCHOOLS

12

Schools also need an adequate supply of emergency medications in the event of a school lock-down or

evacuation. Parent-supplied extra medication and/or school-supplied stock medications (including but

not limited to autoinjectable epinephrine and albuterol inhalers) are among the emergency or urgent care

medications that need to be available in these circumstances.

39

Q9. When certain drugs (e.g., epinephrine autoinjectors) necessary to student care are

unavailable (e.g., due to shortages or exorbitant costs), what alternatives does a school district

have? Is it acceptable to administer expired drugs? What protocols should be in place?

In August 2018, the FDA announced that it would extend the expiration date on some EpiPens by four months,

indicating that expired epinephrine can still potentially save lives. FDA recommends to schools that expired

undesignated (stock) epinephrine autoinjectors should not be discarded until they can be replaced with new

ones. Moreover, schools should allow students to carry or store their prescribed autoinjectors past the expiration

date until in-date autoinjectors become available.

40

School districts should check their state laws regarding

expired medications, as some state nursing regulations do not allow school boards to accept or administer

expired medications, regardless of the FDA’s statement.

All prescription medications brought to school should be in original containers appropriately labeled by the

pharmacist or physician. Except for self-carry medications, they should be stored securely in accordance with

manufacturer directions. Controlled substances must be double-locked. The school nurse, licensed practice

nurse, or delegated, trained UAP must be available and have access to the medications at all times during the

school day. All medications should be returned to the parents at the end of the school year or disposed of in

accordance with existing laws, regulations, and standards.

DRUGS, SUBSTANCE ABUSE, AND PUBLIC SCHOOLS

13

Marijuana 101

Marijuana is a species (Cannabis sativa L.) of the Hemp family of plants, under

the genus Cannabis L, which is also called “hemp.”

41

“Marijuana” is commonly

used interchangeably with “cannabis,” while “hemp” commonly refers to a

cannabis plant that contains less than .3 percent THC (explained below).

42

Marijuana produces resin containing compounds called cannabinoids.

43

The two well-known cannabinoids are tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) and cannabidiol (CBD), both of which

produce drug-like eects in the human body. THC is the main psychoactive component of the cannabis

plant. It is the primary agent responsible for creating the “high” associated with recreational cannabis

use.

44

CBD, on the other hand, is non-psychoactive; it will not get the user “high.” For this reason, CBD

appears more frequently than THC in dietary and natural supplements.

Marijuana is a controlled substance in the U.S., which means its possession is prohibited without specic

licensing.

Medical marijuana use is legal in some states, and some have legalized recreational use.

(See Chart C, p. 39.)

On December 12, 2018, the U.S. Congress passed legislation that will legalize the use of CBD, one of hemp’s

byproducts, at the federal level.

45

This change in federal law likely will lead to increased availability of CBD-

infused products in retail outlets. The law also will permit farmers to legally grow industrial hemp.

46

II. MARIJUANA

Q10. If a student is prescribed or is a registered user of medical marijuana, must a school

district permit the use of the drug on school premises or provide other accommodations for

the individual’s use of medical marijuana?

No. The majority of states that allow the use of medical marijuana by law still bar its consumption in public

places, which includes school property and school buses. Currently Colorado, Delaware, Florida, Illinois, Maine,

New Jersey, Oklahoma, Pennsylvania, Washington, and West Virginia allow specic uses on school grounds, with

parameters. Ohio’s medical marijuana law neither requires a public place to allow the use of medical marijuana,

nor prohibits any public place from allowing the use of medical marijuana.

Colorado, Delaware, Illinois, and New Jersey permit parents to give their child non-smokable medicinal

marijuana-derived products at school. In 2018, Colorado expanded its law to allow school sta to administer

the medication. Maine expanded state regulations to permit medical marijuana use at school, according to the

Education Commission of the States. (See Chart A, p. 26.)

Proposed legislation in California would let school boards decide whether to allow medical cannabis at schools

if a child has a doctor’s note. Currently, the drug cannot be prescribed because, with limited exceptions, it

DRUGS, SUBSTANCE ABUSE, AND PUBLIC SCHOOLS

14

is illegal under federal law — classied as one that has “no accepted medical use.”

47

States that allow use of

cannabis for medicinal purposes require patients and medical providers to register.

Q11. May a school allow a student to use medical marijuana on school grounds without

violating federal law? How does this aect any federal funds the district may receive?

Maybe. Marijuana is still listed on Schedule I of the federal Controlled Substances Act. Some states that permit

the use of medical marijuana on school grounds allow schools to prohibit such use if they lose federal funding

because of implementing that policy.

48

States that allow use of cannabis for medicinal purposes require

patients and medical providers to register.

Some school ocials have expressed opposition to state laws and policy allowing medicinal marijuana use

at school, citing the risk to federal funds, including money for school breakfasts and lunches for low-income

students, which are contingent on schools being drug-free zones. Others, including the California Schools

Boards Association, have supported new laws similar to those adopted in the states of Washington, Florida,

Colorado, New Jersey, and Maine, to enable a governing board to adopt a policy allowing the administration of

medical marijuana on campus where appropriate to create a more accessible education program for students

with severe medical issues that may be treated with marijuana products.

49

State courts have started to address the interaction of state and federal law regarding marijuana use. Some

have ruled that medical marijuana laws do not conict with federal law because they merely carve out a narrow

exemption to criminal prosecution under state law, leaving federal authorities to prosecute at their discretion.

50

Q12. If a school decides to permit student use of medical marijuana, who should administer

it?

Where should it be stored?

States that permit medical marijuana use in schools (currently Colorado, Delaware, Florida, Illinois, Maine, New

Jersey, Oklahoma, Pennsylvania, Washington, and West Virginia) regulate who administers it and how it is stored.

(See Chart A , p. 26.) Delaware and Oklahoma expressly prohibit nurses from administering medical marijuana.

Colorado’s statute directs that the primary caregiver will administer and “remove any remaining medical marijuana

in a nonsmokeable form from the grounds of the preschool or primary or secondary school, the school bus, or

school-sponsored event.”

51

Illinois’ statute contains similar language.

52

(See Chart B, p. 34)

Q13. What steps should school districts take to verify that a student is a registered user of

medical marijuana and that the person administering it is legally permitted to do so?

States authorizing the use of medical marijuana at school specify by statute who must register as both users

and caregivers, and how they must do so. (See Chart A, p. 26.)

School district policies often reect state statutory requirements. For example, the Boonton Township Board of

Education in New Jersey has implemented a medical marijuana policy, which states: “Students authorized to

use medical marijuana, including adult students, are not authorized by law to self-administer the medication

on school grounds, on the school bus or at school sponsored activities. In all cases, a primary caregiver shall be

DRUGS, SUBSTANCE ABUSE, AND PUBLIC SCHOOLS

15

required to assist with the administration of the prescribed medical marijuana on school grounds, on the school

bus, or at school sponsored activities subject to law and this board policy. In order for the prescribed medical

marijuana to be legally administered, the student and primary caregiver shall possess a current registry

identication card. The NJDOH shall issue a registry identication card only upon certication from a licensed

physician in the State with whom a qualifying patient has a bona de physician-patient relationship”.

53

The New Jersey School Boards Association (NJSBA) recommends that if a school board “wishes to create

additional protocols above the legal minimum to verify the registration status and ongoing authorization, a

modied policy version is available upon request [to NJSBA] that contains additional discretionary protocols

for checking registration cards and encouraging the development of an individualized health care plan.”

54

Q14. Can a school prohibit students from possessing, using, or distributing medical

marijuana at school?

States that allow medical marijuana use in schools restrict who may possess the marijuana on school property.

In most instances, possession is limited to the caregiver responsible for administering the marijuana. For

example, Colorado’s medical marijuana statute only allows a “primary caregiver” to possess and administer

the marijuana. Delaware and Illinois likewise limit possession and administration to the primary/designated

caregiver. (See Chart B, p.34) Under no circumstances do state medical marijuana laws allow students to

distribute marijuana on school property.

Q15. Can a school district regulate a student’s legal use of marijuana (whether medical or

recreational) o-campus?

In those states allowing medical marijuana use, a student who holds a valid user’s card is protected from criminal

prosecution. There are no reported court decisions ruling whether a school district could impose discipline on a

student’s statutorily-protected use of medical marijuana o-campus. It is likely such discipline would not be upheld

by the courts. In addition, some states limit school districts’ authority to discipline o-campus student conduct.

55

States that have legalized recreational marijuana restrict its use to individuals 21 years of age or older. It is,

therefore, unlikely that recreational marijuana laws would apply to K-12 students.

DRUGS, SUBSTANCE ABUSE, AND PUBLIC SCHOOLS

16

III. TOBACCO AND RELATED PRODUCTS

Q16. May schools prohibit the possession and use of tobacco products at school by students?

Yes. Courts have consistently found that individuals do not have a constitutionally-protected right to smoke,

except in certain limited contexts involving traditional use of tobacco in religious or cultural ceremonies.

60

To

be found constitutional, laws and policies restricting smoking need only be found to be rationally related to the

legitimate government interest of protecting the health of the public by limiting the eects of second-hand

smoke.

61

In the school context, layers of federal, state, and local law restrict use of tobacco and related products in

school buildings and on school grounds.

The federal Pro-Children Act of 1994, 20 USC §6081 et seq., prohibits any person from allowing smoking in an indoor

educational facility that received federal funding through states or local governments.

62

This federal law specically

allows states and localities to further restrict tobacco use.

63

Whereas the federal law prohibits use of tobacco

indoors, some state laws restrict its use in areas adjacent to school grounds, at school-related events, etc.

64

Q17. May schools prohibit vaping devices, such as e-cigarettes?

Yes. About 49 states, including the District of Columbia, regulate youth access to electronic nicotine delivery systems

(ENDS), or e-cigarettes, requiring that youth be a minimum age to purchase.

65

Some states include e-cigarettes in

the state law denition of tobacco products, and some have started to regulate packaging of e-cigarette products.

66

States have started to pass laws prohibiting the sale, use, and/or possession of ENDS by minors. Maryland,

for example, passed a law adding ENDs to the list of tobacco products retailers are prohibited from selling

to minors, and minors are prohibited from using or possessing, with civil penalties starting at $300 for a

rst violation.

67

School districts in Maryland have informed students that school resource ocers can issue

citations for use or possession of ENDS.

Tobacco and E-Cigarette Use

The health risks of frequent tobacco use have been known for some time, and lawmakers at all levels –

federal, state, and local – have passed regulations to restrict tobacco use to protect both the user and

those who would be subjected to second hand smoke. The CDC reports that although “[t]obacco use

is the leading cause of preventable disease, disability, and death in the U.S…. [e]very day, about 3,200

young people aged 18 or younger try their rst cigarette.”

56

Cigarette smoking rates for both adults and

youth have decreased by half since 1965, but one in seven U.S. adults smokes cigarettes, and about one

quarter of the population is exposed to second-hand smoke. Nine out of 10 smokers report trying their

rst cigarette before age 18.

57

With the rise of alternatives to smoking including e-cigarettes, states are

reporting an increase in youth tobacco use.

58

The CDC estimates that 3.9 million U.S. middle and high

school students use at least one tobacco product.

59

School districts across the country restrict the use of tobacco products by students. Many now address

student use of e-cigarette products.

DRUGS, SUBSTANCE ABUSE, AND PUBLIC SCHOOLS

17

E-cigarettes and Related Products

The CDC reports that ENDS are now the most commonly used tobacco product by young people. These

include e-cigarettes, vape pens, and e-hookahs. An e-cigarette product works by heating a liquid that

contains nicotine, avorings, and other chemicals to create an aerosol that the user inhales into his/her

lungs. There is often a visible vapor – hence the term “vape” or “vaping.” Nicotine is a highly addictive

chemical, potentially harmful to adolescent brain development. The added chemicals in e-cigarette liquids

contain small particles of chemicals such as the avoring diacetyl, which has been linked to a serious lung

disease, and heavy metals including lead.

Although e-cigarette use among U.S. youth decreased in 2016, which may have been due to prevention

and control strategies by federal, state, and local authorities, results from 2018 National Youth Tobacco

Survey showed a dramatic increase in e-cigarette use among youth over the past year.

68

The federal Food and Drug Administration (FDA) regulates tobacco products and prohibits the sale

and distribution of such products to minors.

69

The FDA recently targeted the Juul Labs company, which

makes an e-cigarette product that looks like a USB “thumb” drive, can be re-charged in a USB port, and is

oered in array of avors. The FDA requested that the company come up with a plan to mitigate and slow

widespread use of its products by young people. The company announced in late 2018 that it would no

longer sell most of its avored e-cigarette pods in stores or promote its products in social media.

70

Source:

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention,

https://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/basic_information/e-cigarettes/about-e-cigarettes.html.

Some e-cigarettes are made to look like regular cigarettes, cigars, or pipes.

Some resemble pens, USB sticks, and other everyday items.

DRUGS, SUBSTANCE ABUSE, AND PUBLIC SCHOOLS

18

Q18. Is vaping an acceptable method of administering medical marijuana?

The form of marijuana that may be administered medicinally varies state by state. Some states prohibit the use

of medical marijuana in smokable form, limiting use to non-smokable forms, such as edibles and oils. New York

state, however, allows for vaping medical marijuana, with certain limitations. (See Chart B , p. 34.)

IV. SCHOOL AUTHORITY TO DISCIPLINE AND STUDENT RIGHTS

Q19. What student rights should schools keep in mind when developing policy and making

decisions regarding student discipline for drug involvement?

Students in public schools retain a number of constitutional rights vis-a-vis their schools, though those rights are

not coexistent with those of adults in other settings,

71

and must be considered “in light of the special characteristics

of the school environment.”

72

Although federal courts often defer to the decisions of educators regarding student

discipline, they have recognized constitutional limits to school ocial authority in several contexts.

First Amendment Free Speech. “In the absence of a specic showing of constitutionally valid reasons to regulate

their speech,” the Supreme Court said in 1969, “students are entitled to freedom of expression of their views.”

73

Students have a right to free speech and expressive conduct under the First Amendment, unless that speech

“materially disrupts classwork or involves substantial disorder or invasion of the rights of others,”

74

constitutes a

threat, is obscene or lewd, is school-sponsored speech, or promotes illegal drug use or criminal activity.

75

The Supreme Court has ruled that illegal drug-related speech can be regulated by schools. In Morse v. Frederick,

551 U.S. 393 (2007), the Court decided that a public school could discipline a student who had unfurled a

banner at a school-sanctioned event that read “Bong Hits for Jesus.”

76

Finding the principal reasonably could

have interpreted the banner to promote illegal drug use, and because deterring drug use by schoolchildren is an

“important—indeed, perhaps compelling”public interest, the Court determined that the principal’s action was

constitutionally permissible. The Court noted that “drug abuse can cause severe and permanent damage to the

health and well-being of young people,” that schools have been charged with conveying this message to youth, and

that Congress provided billions of dollars to schools for education programs on the dangers of illegal drug use.

77

Fourth Amendment right against unreasonable search and seizure. The Fourth Amendment “right of the

people to be secure in their persons, houses, papers, and eects, against unreasonable searches and seizures”

arises frequently when school ocials address unauthorized use of drugs in schools. In fact, the key cases

decided by the Supreme Court regarding the Fourth Amendment in schools have arisen in drug and tobacco

search scenarios. In 1985, the Supreme Court decided — in a case involving the search of a student’s purse for

cigarettes, which yielded marijuana and a list of students — that school ocials may search students when it

is reasonable under all the circumstances.

78

Generally, this means the search has to be justied at its inception,

meaning it’s likely to turn up evidence of a violation of law or school rules, reasonably related in scope to the

original reason for the search, and “not excessively intrusive in light of the age and sex of the student and the

nature of the infraction.”

79

The Court decided in 2009 that a school ocial’s search of a 13-year-old student’s

underwear upon suspicion of possession of ibuprofen in violation of school rules was not justied in scope.

80

DRUGS, SUBSTANCE ABUSE, AND PUBLIC SCHOOLS

19

To address a perceived problem with drug use among youth, some districts require drug testing of student

athletes and participants in extra-curricular activities. In 1995, the Supreme Court held that public schools could

conduct random drug tests on student athletes, and in 2002, the Court expanded that authority to students

participating in competitive extracurricular activities generally.

81

Some districts also require drug testing based

on a specic suspicion. A research study indicates that between 1998 and 2011, 14% of middle and 28% of high

school students attended schools with student drug testing, whether random or suspicion-based.

82

Courts deciding drug search cases, including searches by canines, note that the privacy rights of students must

be balanced against the duty of schools to maintain a safe environment conducive to learning, and the reduced

expectations of privacy in students have in school buildings.

83

Fifth Amendment right against self-incrimination. When students are suspected of illegal use of drugs,

school ocials often partner with law enforcement, whether a School Resource Ocer (SRO) or outside

ocer, to investigate. School ocials should keep in mind that students do have some limited rights under

the Fifth Amendment’s guarantee against self-incrimination, especially when law enforcement is involved in an

interrogation. Courts generally have rejected the argument that students must be given a “Miranda warning” of

their right to remain silent during custodial questioning by school ocials,

84

but some state appellate courts

have taken a harder look when the school ocial conducting the interrogation is a school resource ocer and

the questioning results in criminal charges.

85

One state supreme court has ruled that school ocials who searched and questioned a student were not

agents of the police, and therefore not required to provide Miranda warnings, even though the school had a

written agreement with local police to report crimes.

86

In Yarborough v. Alvarado, 541 U.S. 652 (2004), the

Supreme Court held that specic consideration of a defendant’s age is not required when determining whether

the defendant knowingly and voluntarily waived his or her Miranda rights; but in J.D.B. v. North Carolina, 564

U.S. 261 (2011), the Court held that “a child’s age properly informs the Miranda custody analysis,” especially

when the questioning takes place in school. At least one state attorney general has written an opinion stating

that a school ocial who interviews a student at the request or direction of a law enforcement agency must

advise the student of his or her Miranda rights before proceeding.

87

Fourteenth Amendment due process. The Supreme Court has found that when the state has extended

public education as a right under its laws and constitution, a student has a property interest in his education,

and therefore is entitled to some minimal due process – the opportunity to be heard — before he is excluded

from school.

88

A student subject to suspension or expulsion for a drug-related oense, just like other oenses,

must be given an opportunity to tell his side of the story before the discipline is imposed.

It is important to be aware that these federal constitutional protections constitute a “oor” of available rights.

State constitutions and laws, as well as local policy, may provide greater rights. School ocials should consult

with their state school boards association and Council of School Attorneys (COSA) member for specic

standards in their state.

DRUGS, SUBSTANCE ABUSE, AND PUBLIC SCHOOLS

20

Q20. May a school district discipline a student for being under the inuence of a drug or

alcohol while at school? May a school district require an impairment assessment onsite if a

student is suspected of being under the inuence of drugs or alcohol?

Yes, in most cases. Virtually every school district’s code of student conduct prohibits students from being

intoxicated from either drugs or alcohol while at school or at school-sponsored activities.

89

A school district may

require an impairment assessment if state law allows. For example, New York’s Cooperstown Central School

District policy provides for “assessment of any individual who is referred and/or presents with altered perception

or behavior reducing that individual’s ability to function appropriately in the academic environment.”

90

New Jersey law instructs school districts to “adopt and implement policies and procedures for the assessment,

intervention, referral for evaluation, referral for treatment, and enforcement of the code of student conduct,

pursuant to N.J.A.C. 6A:16-7, for students whose use of alcohol or other drugs has aected their school

performance, or for students who consume or who are suspected of being under the inuence of or who

possess or distribute … substances on school grounds pursuant to N.J.S.A. 18A:40A-9, 10, and 11.”

91

Q21. When can a school district require a student to submit to drug or alcohol testing?

Outside of the extra-curricular context detailed above, because a drug or alcohol test would be considered a

“search,” raising Fourth Amendment protections (see Question 19), school ocials would need to have reasonable

suspicion of drug or alcohol use that violated school rules or laws to require a student to submit to such a test.

The U.S. Court of Appeals for the Third Circuit has held that due process rights of a student reasonably suspected

of drug use were not violated by a requirement that she submit to urine and blood tests to determine presence of

drugs.

92

Rumors of drug use likely would not be enough to require a student to take a drug test.

93

Q22. Can a school district require a student to undergo/continue participating in drug/alcohol

treatment as a condition of attending school or participating in extracurricular activities?

Yes, within the context of releasing a student early from a suspension or expulsion, sometimes known as conditional

early reinstatement or abeyance contact, a school district generally may allow a student facing a suspension or

expulsion for a drug or alcohol related infraction to avoid discipline if he/she agrees to a substance abuse program.

The length of the program usually cannot exceed the maximum suspension term for the oense level.

94

Q23. Can a school district prohibit a student found to have committed a drug/alcohol

infraction, whether on or o campus, from participating in extracurricular activities?

Yes, within reason. A school has the right to exclude a student from any extracurricular activities if he/she has

committed a drug or alcohol infraction.

95

It is well-established that participating in extracurricular activities is a

privilege rather than a right. Thus, schools can impose higher disciplinary standards on students who participate

in these activities.

96

The courts reason that extracurricular activities are “usually conducted outside the classroom

before or after regular school hours, usually carry no credit, are generally supervised by school ocials or others,

are academically non-remedial, and are of a voluntary nature for participants.”

97

Due process is not required

when a school denies a student extracurricular participation, unless the school board has established policies for

suspending or expelling students from extracurricular activities.

98

Courts have upheld the suspension of students

DRUGS, SUBSTANCE ABUSE, AND PUBLIC SCHOOLS

21

from interscholastic athletics for violating regulations prohibiting smoking, drinking, use of drugs, or other

disciplinary infractions, including o-campus and o-season conduct, providing the regulations so stipulate.

99

Members of athletic teams and other extracurricular groups (drama, band, debate, cheerleading, and clubs) often

are selected through a competitive process, and students have no property right to be chosen.

100

Q24. What special rules apply to the discipline of IDEA-covered students who are alleged to

have violated the district’s drug policies or federal/state law?

For drug-involved students with disabilities served under the IDEA, school ocials should be mindful of the

requirements of the student’s IEP and remain in consultation with sta familiar with the student’s disability

needs when enforcing school rules and disciplining the student.

If school ocials seek to suspend or expel a student served under the IDEA for more than 10 days, the school

must conduct a manifestation determination to decide whether the conduct was a manifestation of the student’s

disability. If the conduct is a manifestation of the child’s disability, the problem must be addressed through a

functional behavioral assessment and implementation of a behavioral intervention plan. Also, the child must be

returned to the placement from which he or she was removed unless the parents agree to a change.

If the conduct is not a manifestation of the student’s disability, the school system may discipline the student in

the same manner as a nondisabled student but must provide educational services during the removal.

All the procedural protections of the IDEA are available to a child who at the time of the misconduct has not yet

been found eligible for special education if the school had prior “knowledge” that the child had a disability. A

school has “knowledge” of a disability if:

However, the school district can place the student in an interim alternative educational setting for up to 45 school

days, regardless of the manifestation outcome, if the student possesses a weapon; possesses/uses illegal drugs or

sells/solicits controlled substances; or inicts serious bodily harm to someone while on school property.

101

School ocials may, under federal regulations, report a crime committed by a child with a disability to law

enforcement; and law enforcement ocials may exercise their responsibilities to enforce criminal laws

committed by students with disabilities served under IDEA. The school must ensure that the child’s special

education and disciplinary records are transmitted to the entity to which the school reports the crime but must

follow the procedures required by the Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act.

102

This generally will require

parent consent, or a court order or subpoena, which would require parent notice.

• The parent has expressed concern in writing that the child may need special education or has

requested an evaluation;

• The behavior or the performance of the child demonstrates the need for services; or

• A teacher has expressed a specic concern about a pattern of behavior demonstrated by the child

directly to the special education director or other supervisory personnel.

DRUGS, SUBSTANCE ABUSE, AND PUBLIC SCHOOLS

22

Q25. Does student alcoholism or illicit substance use or chemical dependency qualify as a

disability under the IDEA or Section 504/ADA? If so, does this change how a district may

discipline a student found to have committed a drug or alcohol infraction?

Although alcoholism, substance abuse, chemical dependency, or simple use of substances is pervasive among

youth, and often impacts academic progress and social/emotional functioning, chemical abuse and chemical

dependency are not recognized as “disabilities” under the IDEA. Substance use alone does not trigger a school

district’s obligation to evaluate the student for special education eligibility.

Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1974 and its regulations,

103

which prohibit discrimination on the basis of

disability in programs receiving federal nancial assistance, do not protect a student who is currently engaging

in the illegal use of drugs, when a school acts on the basis of such use. People who are no longer engaging

in the illegal use of drugs and in a rehabilitation program are covered, however. Section 504 permits schools

to discipline students with disabilities who use drugs or alcohol to the same degree as students without

disabilities, though alcoholism is not specically excluded from the denition of “disability.”

Q26. What considerations should a school district address in its code of conduct provisions

concerning student involvement with illicit substances?

School ocials should work closely with their state school boards association and COSA member attorney

to determine what topics should be addressed in student codes of conduct with respect to student drug and

substance use, as many criminal oenses and specic procedures will be dictated by state law. Generally, such

policies include the components below.

• Denition of what constitutes a prohibited or restricted “substance” or “drug.” This may include

synthetics, look-alikes, edibles, and prescription drugs used outside of the prescription parameters;

• Descriptions and denitions of the types of drug-related activities that are prohibited, including

what constitutes “possession” and “constructive possession,” as well as locations covered under

the code of conduct;

• Clear explanation of penalties for violations, including the number of oenses;

• Description and notice of the district’s search and seizure policy;

• Description and notice of the district’s interrogation policy;

• Description and notice of the district’s student drug testing policies, including under what

circumstances students will be randomly tested, or tested based on suspicion of drug use;

• Description of the district’s drug-sweep procedures, if any, including use of canines;

• Description of the district’s procedures if a student displays indication of intoxication or drug use at

school, including the odor of marijuana or alcohol.

DRUGS, SUBSTANCE ABUSE, AND PUBLIC SCHOOLS

23

V. STUDENT EDUCATIONAL PERFORMANCE AND DRUG USE

Q27. If school leaders suspect that a student’s educational performance is aected by

his/her established or suspected chemical dependence, what are the school district’s

responsibilities toward that student?

School ocials should explore how they can support the student, starting with a referral to counselors or

other practitioners who see patients with chemical dependency. That process may result in a determination of

whether the student is eligible for special education services.

Q28. Should school districts address a special education student’s chemical dependency in

his/her IEP?

It is generally unwise to address chemical dependency in a student’s IEP. As explained above, chemical

dependency is not a recognized disability category under the IDEA. School districts do not have an obligation to

address behaviors and to established goals related solely to that dependency.

Q29. May a school district delay an educational evaluation of a student it suspects is

actively using chemicals?

Active substance use can aect an educational evaluation in several ways. It can aect academic performance,

interactions with others in the educational environment, and performance on evaluative tests, producing an

inaccurate picture of the student’s current functioning. Substance or chemical use may mimic mental health

disorders, including depression, bipolar disorder, and anxiety. Falsely identifying a student under the category

of “serious emotional disturbance” or “other health impairment” could be harmful to the student, especially

when special education services ignore the problem and enable continued chemical use. For these reasons, a

school district may desire to delay an educational evaluation of a student who is actively using substances.

104

Generally, a school district must follow federal timelines for evaluating a student. Although best practice

dictates that the student abstain from substance use during testing, that abstention is dicult to obtain for a

long enough period to obtain accurate test results. And some state regulations specically say that a student

may not be found eligible under the category of emotional or behavior disorder if the adverse eects on

educational performance is attributable to illegal chemical use.

105

Under federal law, however, a school district cannot delay evaluation of a student to await the student’s

cessation of drug use.

106

School districts have “child nd” responsibility to identify students eligible for service

under IDEA. Generally, a district cannot determine the eect of the student’s chemical use upon his eligibility

without conducting an evaluation.

DRUGS, SUBSTANCE ABUSE, AND PUBLIC SCHOOLS

24

Q30. Can a school district require a student to undergo a chemical health assessment as

part of an educational evaluation?

The IDEA does not prohibit a school district from including a chemical health assessment as part of

an educational evaluation to determine student’s eligibility for special education services. As with all

evaluations, the district will have to obtain parent consent before evaluating the student. Some states protect

communications with chemical dependency counselors as condential information, which may limit the

district’s ability to access or use the evaluation in a due process hearing. It is advisable to inform the parent and

student that the chemical health assessment will not create a counselor-patient privilege and ask the parent

and student to waive any right to assert such a privilege.

107

VI. STUDENT PRIVACY AND DRUG USE

Q31. What does federal law require schools to do to keep student medication and drug

involvement information condential?

Student health records maintained by a school are covered as education records under the Family

Educational Rights and Privacy Act (FERPA),

108

and generally not by the Health Insurance Portability and

Accountability Act (HIPAA).

109

Drug and alcohol treatment records of students kept by any institution receiving federal assistance are

protected under Drug Abuse Oce and Treatment Act (1976) 21 USCA §§1101 , 1102 , 1115 , 1171 , 1177-1179 ,

1181. These requirements apply to all records relating to the identity, diagnosis, prognosis, or treatment of

any student involved in any federally assisted substance abuse program. All records must be maintained in a

locked and secure area. Because these regulations are generally stricter, records to which they apply should be

maintained separately from other educational records. Usually, records may not be disclosed without written

consent of the student. Under applicable state law, minor clients with legal capacity must give consent for

any release of information, including to the minor’s parents. If state law requires parental consent to obtain

treatment, then both parent and student must give consent before disclosure of information.

110

Because these federal regulations and laws may or may not apply to a particular school district’s records

pertaining to a student’s drug involvement, school ocials should consult with the state school boards

association and COSA member attorney when developing records policy.

Q32. How do applicable laws address continuity of care communications between

healthcare providers and school nurses when a student returns to school from inpatient

drug use treatment?

When a student returns to school from an inpatient or outpatient drug or alcohol use treatment, her records

must remain condential. The Condentiality of Alcohol and Drug Abuse Patient Records (CFR Title 42 Part 2)

regulation species restrictions concerning the disclosure and use of patient records that include all records

relating to the identity, diagnosis, prognosis, or treatment of any patient in a substance abuse program that is

DRUGS, SUBSTANCE ABUSE, AND PUBLIC SCHOOLS

25

conducted, regulated, or directly or indirectly assisted by any department or agency of the United States.

111

The

requirements of FERPA and HIPAA must also be considered.

Information contained in records covered by 42 CFR Part 2 can be shared if written consent is obtained. A

minor must always sign the consent form for a program to release information even to his or her parent or

guardian.

112

Some states require programs to obtain parental permission before providing treatment to a

minor.

113

In these states only, programs must get the signatures of both the minor and a parent, guardian, or

other person legally responsible for the minor.

114

42 CFR Part 2 requires patient written records to be in a secure room, locked le cabinet, safe, or other

similar container. The regulations also require programs to adopt written procedures to regulate access to

patients’ records.

115

Some states have outlined strategies regarding a school nurse’s role when addressing a student’s drug

abuse.

116

School nurses should make appropriate referrals to agencies like social services, drug/alcohol

treatment services, behavioral health services, and child protection teams. A school nurse should also solve

ethical dilemmas often associated with substance abuse and assess, support, and participate in community

prevention eorts surrounding substance abuse.

117

RESOURCES

Federal Government

• Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

• Smoking and Tobacco Use main page: https://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/index.htm.

• State Facts Sheets by state, including rates of tobacco and e-cigarette use:

https://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/about/osh/state-fact-sheets/illinois/

• Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration

• Substance Abuse Condentiality Regulations,

https://www.samhsa.gov/about-us/who-we-are/laws-regulations/condentiality-regulations-faqs

• U.S. Department of Health and Human Services

• “E-Cigarette Use Among Youth and Young Adults: A Report of the Surgeon General,”

https://e-cigarettes.surgeongeneral.gov/documents/2016_sgr_full_report_non-508.pdf

Organizations

• American Academy of Pediatrics https://www.aap.org

• National Association of School Nurses https://www.nasn.org

• Public Health Law Center https://publichealthlawcenter.org/

DRUGS, SUBSTANCE ABUSE, AND PUBLIC SCHOOLS

26

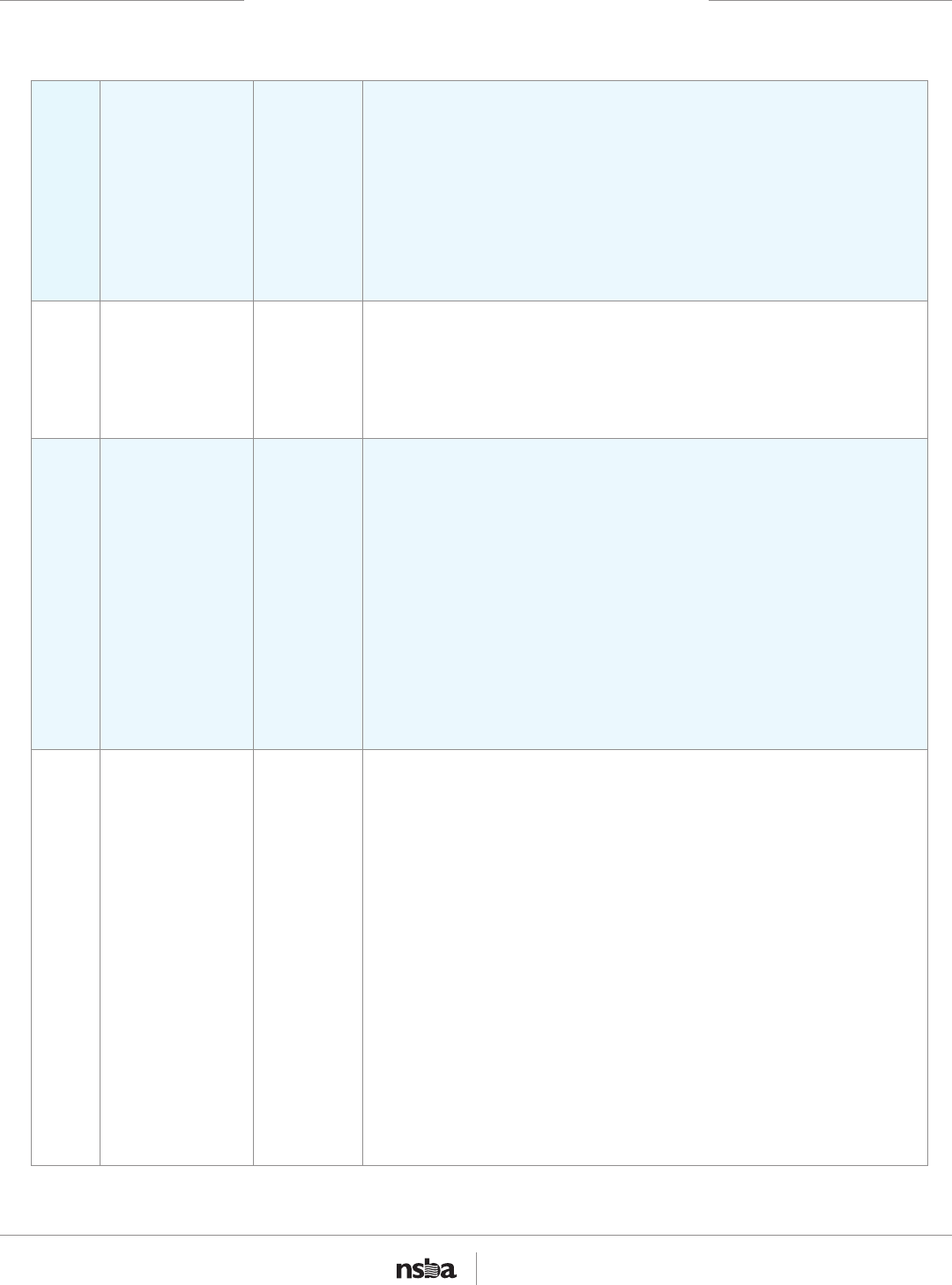

CHART A

STATES PERMITTING MEDICAL MARIJUANA USE BY STUDENTS AT SCHOOL

Colorado: C.R.S.A. § 22-1-119.3

(2)(b) If a school’s administration receives notice from a student’s parent or legal guardian that the student

may be in possession of his or her prescribed medications, the school’s administration shall ensure that such

notice is provided to the student’s teachers and the school nurse or other person who is designated to provide

health services to students at the school.

(3)(c) A student shall not possess or self-administer medical marijuana on school grounds, upon a school bus,

or at any school-sponsored event, except as provided for in paragraph (d) of this subsection (3).

(3)(d)(I)(A) A primary caregiver may possess, and administer to a student who holds a valid recommendation

for medical marijuana, medical marijuana in a nonsmokeable form upon the grounds of the preschool or

primary or secondary school in which the student is enrolled, or upon a school bus or at a school-sponsored

event. The primary caregiver shall not administer the nonsmokeable medical marijuana in a manner that

creates disruption to the educational environment or causes exposure to other students.

(B) After the primary caregiver administers the medical marijuana in a nonsmokeable form, the primary

caregiver shall remove any remaining medical marijuana in a nonsmokeable form from the grounds of the

preschool or primary or secondary school, the school bus, or school-sponsored event.

(II) Nothing in this section requires the school district sta to administer medical marijuana.

(III) A school district board of education or charter school may adopt policies regarding who may act as a

primary caregiver pursuant to this paragraph (d) and the reasonable parameters of the administration and

use of medical marijuana in a nonsmokeable form upon the grounds of the preschool or primary or secondary