DOCTOR OF

NURSING PRACTICE

EDUCATION

in 2022

THE STATE OF

1

Table of Contents

INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................. 2

CONTEXT............................................................................................................. 2

I. SCOPING REVIEW OF RECENT LITERATURE ON DNP CURRICULA AND

EMPLOYMENT ................................................................................................. 4

KEY FINDINGS .................................................................................................... 4

II. REVIEW OF DNP PROGRAM CURRICULA .................................................... 4

KEY FINDINGS .................................................................................................... 5

III. KEY INFORMANT INTERVIEWS: PERSPECTIVES FROM DNP GRADUATES,

EMPLOYERS, AND ACADEMIC LEADERS ............................................................ 6

KEY FINDINGS .................................................................................................... 6

IV. DNP PROGRAM AND GRADUATE TRENDS FROM AACN SURVEY DATA ....... 9

KEY FINDINGS .................................................................................................... 9

V. SURVEY OF DNP GRADUATES’ CHARACTERISTICS, EMPLOYMENT, AND

EXPERIENCES ................................................................................................. 14

KEY FINDINGS .................................................................................................. 17

SUMMARY ........................................................................................................ 27

CONCLUSIONS................................................................................................... 28

RECOMMENDATIONS ....................................................................................... 31

REFERENCES ...................................................................................................... 32

2

Introduction

In July 2020, the Board of Directors for the American Association of Colleges of Nursing (AACN)

voted to move ahead with a new national study to assess the current state of graduates from

Doctor of Nursing Practice (DNP) programs. With a focus on nurses in practice and academia,

the study will consider the current utilization of DNP-prepared nurses, including employer,

faculty, and student perceptions of DNP preparation, as well as the impact of DNPs on patient

and system outcomes, quality of care, leadership, education, and policy development.

In September 2020, AACN issued a request for proposals and selected IMPAQ to complete the

study, which was conducted from February 2021 to February 2022. This document provides a

summary of survey findings as well as recommendations for future steps related to the practice

doctorate in nursing.

Context

In 2004, AACN released a position statement in support of the Doctor of Nursing Practice (DNP)

as the graduate degree for advanced nursing practice preparation, including but not limited to

the four advanced practice registered nurse (APRN) roles: certified registered nurse anesthetist

(CRNA), nurse practitioner (NP), clinical nurse specialist (CNS), and certified nurse-midwife

(CNM; AACN, 2004). Additionally, the Council on Accreditation of Nurse Anesthesia Educational

Programs (COA) requires that all accredited CRNA programs offer a doctoral degree for entry

into practice and, as of January 1, 2022, all students matriculating into an accredited program

must be enrolled in a doctoral program (COA, 2015). Also, in 2019, the National Organization of

Nurse Practitioner Faculties (NONPF), the leading organization for NP education, called for

moving to the DNP degree as the entry-level NP education by 2025 following a DNP summit

attended by 38 leaders from nearly 20 practice, licensure, accreditation, certification, and

educational organizations (NONPF, 2019). However, CNS and CNM organizations have not yet

called for a similar transition.

Until recently, The Essentials of Doctoral Education for Advanced Nursing Practice (AACN, 2006)

have guided the core curricula of DNP programs and competencies that DNP graduates should

have. DNP programs were initially developed using this framework. The competencies in the

original Essentials were focused on quality improvement, systems-level change, and applying

evidence-based practice. These competencies have been broadly attained as multiple surveys

have found that the majority of DNP graduates, including those with a Master of Science in

Nursing (MSN) prior to entering their DNP program, have reported that the DNP improved their

competencies in quality improvement, evidence-based practice, and leadership (Kesten et al.,

3

2022; Minnick et al., 2019). In 2021, AACN released the new Essentials, titled The Essentials:

Core Competencies for Professional Nursing Education (AACN, 2021a). The new Essentials

provide a framework for preparing individuals as members of the discipline of nursing,

reflecting expectations across the spectrum of nursing education and applied experience. These

Essentials are beginning to be implemented in schools.

Given the strong demand for the unique competencies gained by DNP graduates, the demand

for DNP education remains high and continues to grow. The number of DNP programs

increased from 156 in 2010 to 384 in 2020, and the number of enrolled DNP students increased

from 6,599 in 2010 to 35,755 in 2020. Since the completion of this study, new data from AACN

show continued growth, with the number of DNP programs increasing to 394 and the number

of enrollees in 2021 at 40,834 students (AACN, 2022). Despite this consistent increase in the

number of DNP programs and students each year since the introduction of the DNP,

approximately 90% of NPs graduated from master’s-level programs between 2019 and 2020

(AACN, 2021b).

In 2015 AACN sponsored a qualitative study conducted by the RAND Corporation, which

analyzed APRN-focused DNP programs and identified the facilitators and challenges for schools

to transition to the post-baccalaureate DNP program. Challenges included market demand,

institutional barriers, state policy and regulatory structures, university system constraints, and

resource and financial factors (Auerbach et al., 2015). In the 7 years since the publication of

that study, these challenges persist, and DNP curricula and the skill sets of DNP graduates

continue to vary. As a result, questions remain in the nursing profession, as well among

employers and the public, about variation in DNP programs, how DNP graduates are using their

education, and how the skill sets of DNP graduates differ from other graduate-prepared nurses

(McCauley et al., 2020).

This study, titled the State of Doctor of Nursing Practice Education in 2022, builds upon the

RAND study not only by updating the status of the DNP degree and providing new

recommendations 7 years later, but by performing new analyses that provide a comprehensive

picture of the DNP degree. To accomplish this goal, a mixed-methods approach was performed

with a thorough investigation of the status of the DNP degree in 2021–2022, including a

literature review; an analysis of the curricula of 50 nationally representative DNP programs; 42

key informant interviews with DNP graduates, employers, and academic leaders to gather

perceptions about DNP curricula and the skill sets and experience of DNP graduates; an analysis

of AACN survey data to provide a comprehensive picture of DNP student and program trends

between 2005 and 2020; and a survey of over 800 DNP graduates to assess a wide range of

4

topics, such as salary, satisfaction with the DNP degree, and impact of the DNP degree on their

skills and preparation for various types of employment.

The following sections provide brief summaries of and findings from each study activity and end

with conclusions and recommendations.

I. Scoping Review of Recent Literature on DNP Curricula and Employment

A scoping review was conducted of peer-reviewed and other literature published since 2015 to

assess to what extent recent relevant literature has explored DNP curricula and the

employment of DNP graduates. The research questions of the review were as follows:

1. What are the key elements of a DNP education?

2. What types of organizations do DNP graduates work for?

2a. What are their positions at those organizations?

2b. What are their roles and responsibilities in those positions?

Key Findings

● A substantial amount of literature was published between 2015 and 2021 that addressed

the research questions (17 articles for the first research question and 37 articles for the

second research question).

● The variation in DNP graduate skill sets is due primarily to the level of experience a DNP

graduate has prior to entering the DNP program.

● There is agreement among studies that the overall goal of the DNP project is to improve

quality and patient outcomes as well as achieve practice changes. However, there is

significant variability in how the DNP project is implemented among programs.

● Many articles agree that DNP graduates have great potential to impact patient and system-

level outcomes by translating evidence into practice and health policy and by using

leadership skills and interdisciplinary collaboration.

● Many DNP graduates work as direct care providers who require only a master’s degree and

therefore may not be utilizing the full scope of their DNP preparation, and they may not be

recognized for that level of education.

II. Review of DNP Program Curricula

A curriculum review was conducted to assess curriculum variability in DNP programs. The

objectives of this review were to (a) identify the range of variability in DNP programs

throughout the country, (b) assess how this variability affects DNP program quality, and (c)

5

understand how DNP program variability affects employer perceptions of the DNP skill set

versus the skill set of MSN-prepared nurses in the same area of nursing practice. The

researchers sampled 50 Commission on Collegiate Nursing Education (CCNE)-accredited

programs from the 384 nursing schools with DNP programs in 2020 and used the following

factors to assess DNP program variability: educational pathways, DNP program concentrations,

clinical placement methods, clinical site partnerships, credit hours, and DNP Project

requirements.

Key Findings

● The majority of schools in the curriculum review sample had both Bachelor of Science in

Nursing (BSN)-to-DNP and MSN-to-DNP tracks (66%), 24% had only an MSN-to-DNP track,

and 10% had only a BSN-to-DNP track.

● The majority of BSN-to-DNP programs (63%) focus on NP education, 20% on executive and

leadership education, 13% on CRNA education, and the remainder specialize in CNS

education or have a specialization in education or “advanced practice” (a generic category).

● The majority of MSN-to-DNP programs focus on NP education (28%), executive and

leadership education (28%), or are not restricted to a particular specialty (31%). Eight

percent specialize in “advanced practice” (a generic category), and the other 3% include

CNS and CRNA programs.

● For students in a BSN-to-DNP track, there was close to an even three-way split among

securing preceptorships through collaboration between schools and students (33%), giving

students the primary responsibility (31%), and giving schools the primary responsibility

(36%). In MSN-to-DNP tracks, the burden on the students to find preceptors was somewhat

greater; 39% of DNP programs require student–school collaboration, 33% place the primary

responsibility on the students, and 28% place the primary responsibility on the school.

● In our sample, the majority of DNP programs (69%) did not maintain contractual clinical site

partnerships with universities, clinics, or hospitals for guaranteed preceptorships or

graduate placement.

● On average, BSN-to-DNP tracks required 74 credit hours (with the majority being NP

concentrations). On average, MSN-to-DNP tracks required 38 credit hours. The required

number of credits may vary based on entry requirements, number of transfer credits

accepted, etc.

● All DNP programs in the sample required a DNP Project. Most schools followed AACN

recommendations that each DNP Project focuses on a change that impacts healthcare

outcomes and is related to quality improvement. There was significant variability with

6

regards to whether the project is implemented in a clinical setting; the extent to which it is

academic or policy oriented; whether secondary data analysis is permitted; and whether

the project can be carried out by a group.

● Practicum hour requirements were mostly consistent across programs, with about 500 of a

student’s required 1,000 post-baccalaureate practice hours spent practicing clinical skills

and another 500 spent working on the DNP Project. Given the wide range of DNP projects,

there is variability in the number of hours devoted to providing direct care.

III. Key Informant Interviews: Perspectives from DNP Graduates, Employers,

and Academic Leaders

Primary data was collected using in-depth interviews with the following stakeholders: DNP

graduates (14 interviews), employers of DNP graduates (13 interviews), and academic leaders

of DNP programs (15 interviews). We sought to understand the perceptions and experiences of

DNP graduates and employers regarding the value of DNP graduates in the workforce. Key

discussion topics focused on (a) the roles of DNP graduates in the workforce and how their

roles differed from those of master's-prepared nurses, (b) employer perceptions of the DNP

skill set, (c) the potential consequences of DNP program variability on the perceived value of

DNP graduates, and (d) how DNP-prepared nurses can impact patient and system outcomes.

Key Findings

● When asked about the key differences between MSN- and DNP-prepared nurses, most

graduates, employers, and academic leaders indicated that DNP graduates have a larger and

more diverse skill set—particularly in the areas of leadership, evidence-based practice,

critical thinking, and quality improvement—and greater knowledge of policy, economics,

and the business side of nursing.

● Of the 13 employers interviewed, most could not readily identify differences in the

provision of direct patient care by MSN and DNP-prepared nurses. Academic leaders could

not identify differences in clinical skills between MSN and DNP-prepared nurses. This may

relate to the fact that MSN-prepared nurses leave school having completed the same

competencies that prepare them for clinical practice.

● DNP graduates and employers expressed a lack of understanding among employers and

other healthcare professionals about the DNP degree, particularly around the skill sets of

DNP graduates, which roles they should fill, and if the goal is to produce NPs, nurse leaders,

or both.

● Academic leaders and DNP graduates provided similar views on the key differences

between BSN-to-DNP and MSN-to-DNP graduates. Academic leaders noted that differences

7

in advanced practice experience, critical thinking skills, and knowledge between these two

student groups may affect their student experiences and their post-graduation employment

opportunities. DNP graduates felt that students in MSN-to-DNP programs tend to be more

mature and to have many years of clinical and leadership experience. Graduates of the BSN-

to-DNP track are often new APRNs who do not go immediately into a leadership role but

tend to work in clinical practice.

Graduates

● When asked about their motives, most DNP graduates agreed that they were pursuing a

DNP degree to gain specialized knowledge and not necessarily expecting recognition from

their employer or a change in position. It is important to note that 13 out of 14 DNP

graduate interviewees graduated from MSN-to-DNP tracks, so their perspectives may differ

from those who graduated from BSN-to-DNP tracks.

● Many graduates discussed various challenges they encountered while completing the

program. These challenges fell into the following categories: balancing personal life and

coursework, limited time to devote to the DNP project, difficulty securing quality

preceptors, adapting to the demands of coursework or the program, and cost. The biggest

barrier they faced was balancing personal life and coursework.

● When asked about changes in roles and responsibilities, increased compensation, or other

types of employer recognition post-graduation, most DNP graduates indicated that there

was not much change to either responsibilities or salary. However, DNPs in academic roles

reported an increase in salary and responsibilities. Graduates thought that employer

perspectives on the value of the DNP skill set could be changed by changing the leadership

culture and placing more DNPs in executive positions, increasing clinical rigor within DNP

programs to increase credibility, increasing the number of DNP graduates teaching in DNP

programs, and implementing more effective marketing strategies of DNP programs.

● Graduates offered the following suggestions to improve workforce preparation: offer more

in-person (versus online) classes; focus on large-scale systems changes in the curricula;

increase the time spent gaining clinical experience; add business-related classes in areas

such as statistics, finance, communications, project management, and process

improvement; and develop professional skills needed for presentations, building a CV,

working with Microsoft programs, and career placement.

● Overwhelmingly, DNP graduates agreed that they are using evidence-based practices to

change systems and policies in their organization, which is having an impact on patient and

system outcomes.

8

Employers

● Most employers indicated that whether a DNP is required or even preferred depends on the

position. Academic employers agreed that they require a doctoral degree for faculty

positions, with some requiring a DNP specifically, and employers in hospitals or hospital

systems agreed that a DNP is usually only required for leadership and executive positions.

● Most employers want to hire candidates who understand evidence-based practice,

translate science to practice, implement quality improvement policies, and understand

systems change on a larger scale.

● A few employers noted that the student populations of BSN-to-DNP and MSN-to-DNP are

very different in general, with MSN-to-DNP students typically being older with substantially

more clinical experience. They noted that, as a result, different levels of educational support

are needed, and employers perceive that clinical experience prior to the DNP degree is an

important factor in the success of DNP graduates in applying the skills learned in the DNP

program to affect change.

● Employers offered the following suggestions on how to change perceptions of the value of a

DNP degree: increase program and DNP Project rigor, ensure that DNP graduates

demonstrate unique qualifications, change DNP marketing and communications strategies

by clearly explaining the difference between MSN and DNP skill sets, and increasing the

number of DNP graduates who publish articles.

● Of all the employers interviewed, none collected quality metrics to demonstrate the value

of the DNP. While they agreed that this was something they should do, the employers

indicated that they would have to make significant changes to their information technology

systems as they are not set up to track and monitor DNPs.

● When employers were asked how they have seen DNP graduates impact patient and system

outcomes, they mentioned graduates’ enhanced ability to implement higher level or “big

picture” thinking, implement evidence-based practice and quality improvement projects to

improve patient outcomes, and recognize system errors.

● Employers shared the following suggestions for changes to DNP curricula: increase

practicum hour requirements; limit the number of online programs; require publication of

the DNP Project; increase the focus on business education, including finance and statistics;

increase the emphasis on policy and legislation; and include social media training.

9

Academic Leaders

● Academic leaders believe that most students pursue a DNP degree for career advancement

in nursing leadership roles, advanced nursing practice, or academia. Another reason stated

was students are anticipating that an advanced degree will likely be required in the future.

● Academic leaders described several challenges that students may face in completing their

DNP degree, including working while attending graduate programs, the cost of the DNP

degree, and balancing competing life priorities. They reported that many students work full-

time while in school and that the COVID-19 pandemic has substantially increased their

workloads.

● Academic leaders reported that many DNP graduates return to the same organizations and

positions that they had before obtaining their degree. They explained that DNP graduates

often play a greater role in their organizations and that their employers occasionally provide

financial support to facilitate degree completion.

● Academic leaders expect that DNP graduates will positively impact patient outcomes at a

system level, given their leadership skills and expert knowledge in areas such as population

health and evidence-based practice.

● Academic leaders suggest that there is a need to address DNP program variability;

strengthen DNP curricula, specifically coursework in leadership, writing, communication,

finance, patient-centered care, quality, safety, and population health; include education

courses for DNP graduates pursuing an academic career; and communicate the value of the

DNP degree to key stakeholders.

IV. DNP Program and Graduate Trends from AACN Survey Data

An analysis of AACN survey data from 2005 to 2020 demonstrates how DNP program numbers

and DNP student enrollment have grown over time. Analyses of DNP student demographics,

DNP program tracks and concentrations, and associations between DNP program growth and

school characteristics are provided.

Key Findings

● The number of DNP programs and enrolled DNP students have increased every year

since the inaugural DNP programs in 2005. The number of DNP programs increased

from 156 in 2010 to 384 in 2020. Figure 1 shows the growth in DNP programs. In 2005,

only 13 schools had DNP programs; the number of DNP programs has increased steeply

every year since then. In just 5 years, between 2005 and 2010, the number of DNP

programs increased more than tenfold, from 13 to 156. Between 2010 and 2013, the

number of DNP programs continued to increase at a rapid pace, from 156 to 254. Since

10

2013, the number of DNP programs has increased every year, but at a slower pace. In

2020, there were 384 active DNP programs. The number of enrolled DNP students

increased from 6,599 in 2010 to 35,755 in 2020. In 2011, AACN reported that 867 DNP

applications were qualified but not offered admission, and in 2020, 3,664 DNP

applications were qualified but not offered admission (AACN 2012, 2021).

Figure 1: Number of Active DNP Programs 2005-2020

Note. These results differ slightly from the number of DNP programs in the annual AACN enrollment and

graduation reports because of differences in how DNP programs operated as a consortium.

● Figure 2 depicts the number of DNP programs in each state as of 2020. Each state has at

least one DNP program, with the larger number of programs concentrated in the East and in

California and Texas. The states with the highest number of DNP programs (21–30) are

Pennsylvania and Illinois.

11

Figure 2: Number of DNP Programs by State 2020

● DNP students are mostly female, although the percentage of female students is gradually

decreasing over time, from the low 90s pre-2012 to 86% in 2020.

● Figure 3 displays the racial/ethnic distribution alternatively by displaying the percentage of

all non-White students each year. Since 2006, the percentage of non-White students in DNP

programs has increased each year, from 13% in 2006 to 37% in 2020. This confirms that

racial/ethnic diversity has been increasing steadily in DNP programs. This trend seems likely

to continue, as racial/ethnic diversity has increased substantially in the last 15 years.

Figure 3: Percentage of Racial/Ethnic Minority DNP Students, 2005-2020

Note. Excludes international students and unknown/not reported race/ethnicity. Students were counted once for

each year they were in a DNP program.

12

● The number of programs that offer a BSN-to-DNP track has increased over time, but mostly

in conjunction with an increase in MSN-to-DNP tracks. In 2020, 65% of programs had both

tracks, and 30% had only an MSN-to-DNP track.

● Figure 4 presents the number of MSN-to-DNP and BSN-to-DNP students between 2005 and

2020. In 2010, 1,906 (27%) were in a BSN-to-DNP track, while the majority 5,149 (73%) were

in an MSN-to-DNP track. Between 2010 and 2020, while enrollment in tracks of both types

increased substantially, BSN-to-DNP enrollment increased at a faster pace. In 2020, 22,574

DNP students (57%) were in a BSN-to-DNP track, and 16,956 (43%) were in an MSN-to-DNP

track.

Figure 4: Number of DNP Students by Track, Excluding Direct Entry, 2005–2020

Note. Excludes students enrolled in direct entry programs, which were in the data for the first time in 2020.

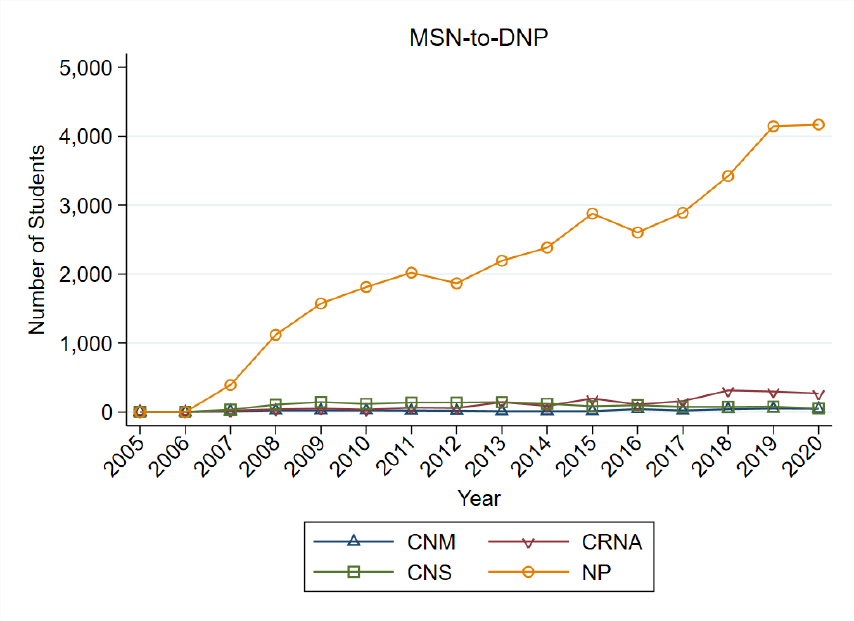

● Figures 5 and 6 show the number of DNP students in APRN programs by APRN

concentration and track. In the BSN-to-DNP track, the number of students with an NP

concentration rose rapidly in 2009, and that concentration has been the most rapidly

increasing APRN concentration ever since. However, since 2013, the number of students

with a CRNA concentration in the BSN-to-DNP track also has grown rapidly. The numbers of

BSN-to-DNP students in CNS and CNM concentrations were very small (2%) in all years. In

13

2020, there were 16,947 BSN-to-DNP students in an NP concentration (78%) and 4,341 BSN-

to-DNP students in a CRNA concentration (20%). Similarly, nearly all MSN-to-DNP students

in an APRN concentration were in an NP concentration (between 86% and 92%).

Figure 5. Number of BSN-to-DNP Students in an APRN Concentration by APRN Concentration

and Track, 2005–2020

Note. Excludes schools that wrote in one of the APRN specialties instead of selecting the appropriate APRN option

on the survey

14

Figure 6. Number of MSN-to-DNP Students in an APRN Concentration by APRN Concentration

and Track, 2005–2020

Note. Excludes schools that wrote in one of the APRN specialties instead of selecting the appropriate APRN option

on the survey. Although the majority of concentrations reported in AACN’s Enrollment and Graduation Survey data

are write-ins for the MSN-to-DNP track, only about 10% of schools had responses that contained combinations of

letters that correspond to APRNs, so the data on APRN concentrations appear to be accurate, with a relatively

small margin of error.

V. Survey of DNP Graduates’ Characteristics, Employment, and Experiences

A survey was conducted of DNP graduates online and through the mail with a sample

comprised of 875 eligible respondents, including DNP graduates working as APRNs, nurse

executives or administrators, and faculty. Questions covered DNP characteristics, employment,

and experiences, including satisfaction with the DNP degree, salary, and perceptions of specific

skills and preparation. Descriptive statistics for key data, including respondent demographics

and employment are presented. Regression analyses show how outcomes such as satisfaction

with the DNP degree, the DNP skill sets, and the perceived impact of the respondents’ DNP

education are associated with employment, school, and individual characteristics.

15

Table 1. Demographic Characteristics of DNP Survey Respondents

All respondents

Race, n (%)

White

731 (87%)

Black/African American

72 (9%)

Asian

26 (3%)

American Indian or Alaskan, Native Hawaiian or Other

Pacific Islander

a

12 (1%)

Other

34 (4%)

Hispanic or Latino origin

44 (5%)

Age category, n (%)

Age 25–34

49 (6%)

Age 35–44

134 (16%)

Age 45–54

208 (25%)

Age 55–64

310 (37%)

Age 65–100

131 (16%)

Age received DNP degree, n (%)

Age 25–34

96 (12%)

Age 35–44

177 (21%)

Age 45–54

296 (36%)

Age 55–64

239 (29%)

Age 65–100

18 (2%)

Census region of employer, n (%)

Northeast

132 (16%)

Midwest

170 (21%)

South

350 (43%)

West

153 (19%)

Advanced nursing role, n (%)

NP

274 (33%)

CRNA

69 (8%)

CNM

116 (14%)

CNS

36 (4%)

Nurse executive

211 (25%)

Other (primarily identified as a nurse educator/faculty)

127 (15%)

Primary employment position, n(%)

NP

146(18%)

16

CRNA

59 (7%)

CNM

68 (8%)

CNS

b

—

Nurse Executive

82 (10%)

Administrator

92 (11%)

Nurse faculty

187 (23%)

DNP Track, n(%)

BSN-to-DNP

110(13%)

MSN-to-DNP

498(57%)

MS-to-DNP

132 (15%)

Direct entry

73(8%)

Other

57(7%)

DNP Program Delivery, n(%)

100% online

263(30%)

100% in person

82(9%)

Blended 50% or more online

364(42%)

Blended with less than 50% online

155(18%)

Primarily Full-time versus Part-time Student, n(%)

Full-time student

488(56%)

Part-time student

372(43%)

Other

10(1%)

Note. The under 24 age category is omitted to protect privacy due to a very small sample size. The number of

respondents for each demographic characteristic varied slightly for each question because not all respondents

answered each question. Race/ethnicity percentages sum to more than 100 because survey recipients were

instructed to indicate all categories that applied.

a

Data for the categories of “American Indian or Alaskan” and “Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander” were

collected separately but were combined in the reporting to protect the confidentiality of the respondents.

B

The percentages do not add to 100 for “Primary employment position” because the “Other” category is not

reported to protect the confidentiality of respondents. “—” indicates there were fewer than 10 respondents, in

which case the number was not reported to maintain confidentiality.

17

Key Findings

● Respondents were highly satisfied with their decision to obtain a DNP degree; 95% were

satisfied, including 71% who were “extremely satisfied.”

● The respondents were mostly White (87%) and over 45 years old (25% were aged 45–54,

37% were aged 55–64, and 16% were aged 65–100). A plurality (43%) was from the South.

● As with age and location, respondents had a diverse range of advanced nursing roles and

primary employment positions. The largest number of respondents were NPs (33%),

followed by nurse executives (25%), other advanced nursing roles (15%), CNMs (14%),

CRNAs (8%), and CNSs (4%). For all respondents, 33% were working in APRN roles (with the

majority working as NPs), 21% were working in an administrative or executive role, and 23%

were serving as faculty. These percentages may not be representative of the universe of

DNP graduates; they result from using professional associations to construct the sample.

● The majority of respondents graduated from a master’s-to-DNP track, with 57% in an MSN-

to-DNP track, 15% in a Master of Science (MS)-to-DNP track, and 13% in BSN-to-DNP, 8% in

direct entry program, and 7% in another track (e.g., MBA-to-DNP, MPH-to-DNP, etc.).

● As expected, the respondents who received their DNP in a master’s-to-DNP track graduated

at substantially older ages, with 40% of respondents in an MSN-to-DNP track graduating

between 45 and 54 years old and 30% graduating between 55 and 64 years old. Among

respondents in a BSN-to-DNP track, 45% graduated between 25 and 34 years old, and 33%

graduated between 35 and 44 years old. Interestingly, among respondents who received

their DNP through a direct entry program, 76% graduated between 45 and 64 years old,

similar to the percentage of respondents in master’s-to-DNP tracks who graduated in that

age range.

● Respondents working as APRNs were more involved in precepting students, and

respondents working as nurse executives precepted the fewest students. Fifteen percent of

respondents received renumeration for precepting students. The most common kind of

renumeration was a direct payment (41%), followed closely by complimentary continuing

education (39%) and less closely by an honorarium (27%). Less than 10% of respondents

received either tuition reduction or a different type of renumeration.

● Seventy-two percent of respondents attended DNP programs that were at least 50% online,

with 30% attending fully online programs and 42% attending blended programs with 50% or

more of the content online. The rest of the respondents attended fully in-person programs

(9%) or programs that were blended but less than 50% online (18%). Finally, 56% of

respondents were primarily full-time students in their DNP programs, while 43% were

primarily part-time students.

18

Regression Analysis - Regressions were used to analyze the correlations between DNP program

and individual characteristics and outcomes of interest. Outcomes of interest include

respondents’ satisfaction with their decision to obtain a DNP, skills qualified or prepared to do

after obtaining a DNP, skills improved following their DNP program, and positive impacts of

DNP education. A linear probability model was used to explore the correlations between these

outcomes and primary employment position, DNP program delivery, DNP program track,

whether the respondent was primarily a part-time or full-time student, and age. The estimates

represent associations, not causal relationships. They can be interpreted as the relationship

between characteristics and reports of skills/outcomes, conditional on other included

characteristics.

Table 2 presents a regression analysis of correlations between primary employment position,

DNP program delivery, DNP program track, whether the respondent was primarily a part-time

or full-time student, and age, with an “extremely satisfied” response to the question “How

satisfied are you with your decision to obtain a DNP degree?” The analysis was conducted using

correlations with “extremely satisfied” responses because 71% of respondents had this

response, while 94% of respondents were “extremely satisfied” or “moderately satisfied” with

their decision to obtain a DNP degree.

Respondents working as administrators (28%), nurse executives (23%), nurse faculty (14%), and

other positions (13%), relative to NPs, were more likely to be extremely satisfied with their

decision to obtain a DNP degree. Respondents primarily part-time in their DNP program were

9% less likely to be extremely satisfied with their decision to obtain a DNP degree, relative to

full-time. Respondents were increasingly extremely satisfied with their decision to obtain a DNP

degree relative to their age, with respondents aged 55 and older being significantly more likely

to be extremely satisfied than respondents under 35.

Table 2. Regression Analysis of Satisfaction With Decision to Obtain a DNP Degree

Extremely satisfied (N=764)

r(SE)

NP (Reference Category)

---

Administrator

0.28** (0.06)

CNM

-0.07 (0.07)

CRNA

-0.01 (0.07)

CNS

-0.13 (0.16)

Nurse executive

0.23** (0.06)

19

Extremely satisfied (N=764)

r(SE)

Nurse faculty

0.14** (0.05)

Other primary employment position

0.13* (0.05)

BSN-to-DNP (Reference Category)

---

MSN-to-DNP

a

0.07 (0.06)

MS-to-DNP

0.04 (0.07)

Direct entry

0.09 (0.08)

Other DNP track

-0.07 (0.08)

100% in person (Reference Category)

---

100% online DNP program

-0.05 (0.06)

Blended DNP program delivery

-0.01 (0.06)

Full-time (Reference Category)

---

Primarily part-time DNP student

-0.09** (0.03)

Other full-time or part-time status

-0.15 (0.14)

Age Under 35 (Reference Category)

---

Age 35–44

0.06 (0.08)

Age 45–54

0.09 (0.08)

Age 55–64

0.17*(0.08)

Age over 65

0.23** (0.09)

Note. A constant term is included in the regression but not reported.

* p < .05. ** p < .01.

a. While MSN-to-DNP and MS-to-DNP are modeled separately, it is recognized that these

programs are essentially the same. Note that the coefficients for the programs are similar.

20

Table 3 presents a regression analysis of correlations between primary employment position,

DNP program delivery, DNP program track, whether the respondent was primarily a part-time

or full-time student, and age, with responses to the question “Since you obtained a DNP

degree, which of the following do you feel qualified or prepared to do?” “Scholarship” is a

combination of these two sub-items: “Write for publication” and “Give presentations (regional,

national, international).” “Improved direct care” is a combination of “Provide improved direct

care services” and “Provide specialized direct care services.”

Administrators, nurse executives, nurse faculty, and other positions are more likely to be

prepared as compared to NPs to perform quality improvement and leadership activities, while

being less prepared to provide improved direct care. Nurse faculty and DNPs in other positions

are also much more likely than NPs to be prepared for scholarship activities (contributing to

publications and preparing and giving presentations). Controlling for the age of respondents,

which serves as a proxy for experience, there are no significant differences in preparation

between respondents who were in different DNP tracks, except for respondents in an MSN-to-

DNP track were significantly more likely to be prepared for scholarship activities. Respondents

who were primarily part-time DNP students felt less prepared for quality improvement and

leadership activities than respondents who were mostly full-time DNP students. Finally, for all

four categories of activities, respondents older than age 35 felt at least as well prepared as

respondents younger than age 35, with significant differences for quality improvement (age 35

and above), research (age 65 and above), and leadership (age ranges 35–44, 45–54, and 55–64).

Table 3. Regression Analysis of Activities that Respondents Feel Prepared to Do After

Obtaining a DNP Degree

Quality

improvement

(N=764)

r(SE)

Scholarship

(N=764)

r(SE)

Leadership

(N=764)

r(SE)

Improved direct

care (N=764)

r(SE)

NP (Reference Category)

---

---

---

---

Administrator

0.20**

(0.06)

0.18 (0.10)

0.21** (0.05)

-0.42** (0.12)

CNM

0.08 (0.07)

0.03 (0.11)

-0.01 (0.05)

-0.05 (0.13)

CRNA

-0.01

(0.07)

-0.08 (0.11)

-0.09 (0.06)

-0.03 (0.14)

CNS

0.26 (0.16)

0.04 (0.25)

-0.09 (0.13)

-0.07 (0.31)

Nurse executive

0.21**

(0.06)

0.11 (0.10)

0.18** (0.05)

-0.70** (0.12)

Nurse faculty

0.13*

(0.05)

0.29**

(0.08)

0.17** (0.04)

-0.51** (0.10)

21

Quality

improvement

(N=764)

r(SE)

Scholarship

(N=764)

r(SE)

Leadership

(N=764)

r(SE)

Improved direct

care (N=764)

r(SE)

Other primary employment

position

0.18**

(0.05)

0.16* (0.08)

0.14** (0.04)

-0.52** (0.10)

BSN-to-DNP (Reference

Category)

---

---

---

---

MSN-to-DNP

a

-0.02

(0.06)

0.254**

(0.09)

-0.04 (0.05)

0.03 (0.12)

MS-to-DNP

-0.05

(0.07)

0.19 (0.11)

-0.02 (0.06)

0.14 (0.14)

Direct entry

0.04 (0.08)

0.31* (0.12)

0.01 (0.06)

-0.09 (0.15)

Other DNP track

-0.08

(0.08)

0.06 (0.13)

-0.04 (0.07)

0.07 (0.17)

100% in person (Reference

Category)

---

---

---

---

100% online DNP program

0.09 (0.06)

-0.06 (0.10)

-0.01 (0.05)

-0.04 (0.12)

Blended DNP program delivery

0.07 (0.06)

0.02 (0.09)

0.01 (0.05)

0.05 (0.11)

Full-time (Reference Category)

---

---

---

---

Primarily part-time DNP

student

-0.08*

(0.03)

-0.08 (0.05)

-0.08** (0.03)

-0.04 (0.06)

Other full-time or part-time

status

-0.07

(0.14)

-0.07 (0.22)

-0.03 (0.11)

0.20 (0.28)

Age under 35 (Reference

Category)

Age 35–44

0.17*

(0.08)

0.15 (0.12)

0.20** (0.06)

0.09 (0.16)

Age 45–54

0.18*

(0.08)

0.16 (0.13)

0.19** (0.06)

0.22 (0.16)

Age 55–64

0.18*

(0.08)

0.21 (0.13)

0.18** (0.06)

0.17 (0.16)

Age over 65

0.22*

(0.09)

0.26 (0.14)

0.09 (0.07)

0.02 (0.17)

Note. A constant term is included in the regression but not reported.

* p < .05. ** p < .01.

a. While MSN-to-DNP and MS-to-DNP are modeled separately, it is recognized that these

programs are essentially the same. Note that the coefficients for the programs are similar.

22

Table 4 presents a regression analysis of correlations and (standard errors) between primary

employment position, DNP program delivery, DNP program track, whether the respondent was

primarily a part-time or full-time student, and age, with responses to the question “Which of

the following skill sets improved after obtaining your DNP degree?” The category

“Organizational change/quality improvement” is a combination of the two subitems

“Organizational change” and “Quality improvement.”

Consistent with the data on the activities respondents feel prepared to perform (as reported in

Table 3), administrators, nurse executives, and other positions were more likely than NPs to

report improvements in both policy advocacy and organizational change/quality improvement

skill sets. Respondents who had been in an MSN-to-DNP track reported larger improvements in

both skill sets than respondents who had been in a BSN-to-DNP track.

Table 4. Regression Analysis of Skill Sets That Improved After Obtaining a DNP Degree

Organizational

change/

quality improvement

(N=760)

r(SE)

Policy

advocacy

(N=760)

r(SE)

NP (Reference Category)

---

---

Administrator

0.34** (0.11)

0.18* (0.07)

CNM

-0.10 (0.12)

0.12 (0.08)

CRNA

-0.18 (0.13)

0.02 (0.08)

CNS

0.22 (0.28)

-0.14 (0.18)

Nurse executive

0.25* (0.11)

0.24** (0.07)

Nurse faculty

0.07 (0.09)

0.11 (0.06)

Other primary employment position

0.19* (0.09)

0.13* (0.06)

BSN-to-DNP (Reference Category)

---

---

MSN-to-DNP

a

0.29** (0.10)

0.15* (0.07)

MS-to-DNP

0.27* (0.12)

0.10 (0.08)

Direct entry

0.20 (0.14)

0.13 (0.09)

Other DNP track

0.06 (0.15)

0.16 (0.10)

100% in person (Reference Category)

---

---

100% online DNP program

0.14 (0.11)

0.02 (0.07)

Blended DNP program delivery

0.18 (0.10)

0.07 (0.07)

Full-time (Reference Category)

---

---

Primarily part-time DNP student

-0.01 (0.06)

-0.03 (-0.04)

23

Organizational

change/

quality improvement

(N=760)

r(SE)

Policy

advocacy

(N=760)

r(SE)

Other full-time or part-time status

0.63* (0.26)

0.20 (0.17)

Age under 35 (Reference Category)

---

---

Age 35–44 (omitted = under 35)

0.23 (0.14)

0.03 (0.09)

Age 45–54 (omitted = under 35)

0.06 (0.14)

-0.03 (0.09)

Age 55–64 (omitted = under 35)

0.06 (0.14)

0.02 (0.09)

Age over 65 (omitted = under 35)

-0.07 (0.16)

0.06 (0.10)

Note. A constant term is included in the regression but not reported.

* p < .05. ** p < .01.

a. While MSN-to-DNP and MS-to-DNP are modeled separately, it is recognized that these

programs are essentially the same. Note that the coefficients for the programs are similar.

Table 5 presents a regression analysis of correlations between primary employment position,

DNP program delivery, DNP program track, whether the respondent was primarily a part-time

or full-time student, and age, with “positive impact” responses to the question “What was the

impact, if any, on the following after obtaining a DNP degree?”

Nurse executives were, on average, 22 percentage points less likely than NPs to believe that

their preparation to work in a clinical setting improved as a result of their DNP degree.

Additionally, DNP graduates in a BSN-to-DNP track are far more likely (about 30 percentage

points on average) to have increased their preparation to practice in a clinical setting while

obtaining a DNP degree. This result may stem from two factors: 1) BSN-to-DNP graduates may

be less prepared than master’s-prepared students to practice in a clinical setting when entering

a DNP program, and 2) BSN-to-DNP tracks focus more on APRN concentrations and preparing

for clinical practice than do MSN-to-DNP tracks.

Relative to working as an NP, working as an administrator, nurse executive, or nurse faculty

member in most cases, is significantly positively associated with whether obtaining a DNP

degree impacted employment experiences (other than preparation for clinical practice). This

includes reported positive effects on how their employers assess their value, realizing

professional goals, career fulfillment, responsibilities at their place of employment, and respect

from colleagues. The only two exceptions are the impact on career fulfillment for nurse

executives and nurse faculty, as the estimates suggest there is no significant difference in the

DNP degree’s impact on their career fulfillment and its impact on the career fulfillment

experienced by NPs. The estimates for nurse executives and administrators have a larger

24

magnitude than the estimates for nurse faculty in almost all cases. CNMs are less likely than

NPs to see an impact of the DNP degree on their responsibilities and respect from colleagues,

while CRNAs are less likely than NPs to see an impact on employer assessment of their value

and career fulfillment.

Compared with being a full-time student, being primarily a part-time student is less likely to

have an impact on employer assessment of value and on career fulfillment. Finally, program

delivery (online versus in person) was not estimated to have any significant effect on any

outcomes.

Table 5. Regression Analysis of Impact on Employment Experiences After Obtaining a DNP

Degree

Preparation

to practice in

a clinical

setting

(N=755)

r(SE)

How

employer

assesses

your value

(N=759)

r(SE)

Realizing

professional

goals

(N=759)

r(SE)

Career

fulfillment

(N=760)

r(SE)

Responsibilities

at place of

employment

(N=757)

r(SE)

Respect

from

colleagues

(N=758)

r(SE)

NP

(Reference

Category)

---

---

---

---

---

---

Administra

tor

-0.05

(0.07)

0.26**

(0.07)

0.12**

(0.04)

0.12*

(0.05)

0.32**

(0.07)

0.23**

(0.06)

CNM

-0.01

(0.07)

-0.11

(0.07)

0.03

(0.05)

-0.11

(0.06)

-0.15*

(0.07)

-0.13*

(0.07)

CRNA

-0.15

(0.08)

-0.17*

(0.08)

-0.09

(0.05)

-0.14*

(0.06)

-0.02

(0.08)

-0.08

(0.07)

CNS

-0.01

(0.183)

0.21

(0.18)

-0.13

(0.12)

0.18

(0.14)

-0.04

(0.18)

0.08

(0.17)

Nurse

executive

-0.22**

(0.07)

0.25**

(0.07)

0.11*

(0.05)

0.01

(0.05)

0.26**

(0.07)

0.25**

(0.06)

Nurse

faculty

-0.02

(0.06)

0.22**

(0.06)

0.10*

(0.04)

0.06

(0.04)

0.28**

(0.06)

0.12*

(0.05)

Other

primary

employme

nt position

-0.04

(0.06)

0.12*

(0.06)

0.06

(0.04)

0.01

(0.05)

0.18**

(0.06)

0.15**

(0.05)

BSN-to-

DNP

25

Preparation

to practice in

a clinical

setting

(N=755)

r(SE)

How

employer

assesses

your value

(N=759)

r(SE)

Realizing

professional

goals

(N=759)

r(SE)

Career

fulfillment

(N=760)

r(SE)

Responsibilities

at place of

employment

(N=757)

r(SE)

Respect

from

colleagues

(N=758)

r(SE)

(Reference

Category)

MSN-to-

DNP

a

-0.35**

(0.06)

-0.04

(0.06)

-0.07

(0.04)

-0.04

(0.05)

-0.09

(0.06)

0.05

(0.06)

MS-to-DNP

-0.28**

(0.07)

-0.03

(0.07)

-0.04

(0.05)

0.00

(0.06)

-0.10

(0.07)

0.06

(0.07)

Direct

entry

-0.34**

(0.08)

-0.06

(0.08)

-0.05

(0.06)

-0.06

(0.07)

-0.17*

(0.08)

-0.01

(0.08)

Other DNP

track

-0.29**

(0.09)

-0.03

(0.09)

-0.11

(0.06)

-0.07

(0.07)

-0.20*

(0.09)

-0.04

(0.08)

100% in

person

(Reference

Category)

---

---

---

---

---

---

100%

online DNP

program

-0.12

(0.07)

-0.07

(0.07)

-0.03

(0.05)

-0.05

(0.05)

-0.13

(0.07)

0.01

(0.06)

Blended

DNP

program

delivery

-0.07

(0.06)

-0.05

(0.06)

-0.02

(0.04)

-0.06

(0.05)

-0.10

(0.06)

-0.02

(0.06)

Full-time

(Reference

Category)

---

---

---

---

---

---

Primarily

part-time

DNP

student

0.02

(0.04)

-0.08*

(0.04)

-0.03

(0.02)

-0.07*

(0.03)

0.01

(0.04)

-0.05

(0.03)

Other full-

time or

part-time

status

-0.02

(0.15)

-0.17

(0.15)

-0.23*

(0.11)

-0.13

(0.12)

-0.07

(0.15)

-0.19

(0.14)

26

Preparation

to practice in

a clinical

setting

(N=755)

r(SE)

How

employer

assesses

your value

(N=759)

r(SE)

Realizing

professional

goals

(N=759)

r(SE)

Career

fulfillment

(N=760)

r(SE)

Responsibilities

at place of

employment

(N=757)

r(SE)

Respect

from

colleagues

(N=758)

r(SE)

Age under

35

(Reference

Category)

---

---

---

---

---

---

Age 35–44

-0.04

(0.09)

-0.04

(0.09)

-0.09

(0.06)

0.06

(0.07)

0.04

(0.09)

0.04

(0.08)

Age 45–54

-0.06

(0.09)

-0.15

(0.09)

-0.02

(0.06)

0.10

(0.07)

-0.01

(0.09)

-0.05

(0.08)

Age 55–64

-0.20*

(0.09)

-0.01

(0.09)

-0.01

(0.06)

0.11

(0.07)

0.05

(0.09)

0.06

(0.08)

Age over

65

-0.16

(0.10)

-0.00

(0.09)

-0.02

(0.06)

0.16*

(0.08)

0.01

(0.10)

0.12

(0.09)

Note. A constant term is included in the regression but not reported.

* p < .05. ** p < .01.

a. While MSN-to-DNP and MS-to-DNP are modeled separately, it is recognized that these

programs are essentially the same. Note that the coefficients for the programs are similar.

27

Summary

In 2004, AACN released a position statement supporting the DNP as the graduate degree for

advanced nursing practice preparation, including but not limited to the four APRN roles. While

most of the recommendations within that report have been widely implemented, most

advanced nursing practice preparation remains at the master’s level. A qualitative study

published in 2015 by the RAND Corporation and sponsored by AACN analyzed APRN-focused

DNP programs and identified the facilitators and challenges for schools to transition to the

post-baccalaureate DNP program. Since the publication of that report, the number of DNP

programs, students, and enrollments has continued to grow rapidly.

As discussed in this report and in recent literature, DNP graduates gain unique skillsets through

their DNP education, including advanced preparation in quality improvement, evidence-based

practice, and leadership. While these skills are prevalent in DNP graduates (as they are a

universal focus of DNP programs), the experience and education of students entering DNP

programs, the curriculum of DNP programs, and perceptions of the DNP degree by DNP

graduates, employers, and academic leaders are diverse. Confusion around the DNP may stem

from the fact that the DNP education prepares graduates for a broad range of roles involving

clinical skills for direct care, quality improvement, application of evidence-based practice,

policy, research, leadership, business, and finance. This may be driven in part by the large

variation in clinical skills, experience, and professional interests of DNP students, particularly

those in BSN-to-DNP and MSN-to-DNP tracks.

The variation in program focus may lead to confusion regarding what skills DNP graduates have

and thus what value they bring to their professional positions. In particular, some employers

struggle to understand what distinguishes DNP graduates from other nurses with advanced

degrees. Conversely, many DNP graduates struggle to get their employers to understand and

recognize their unique skill sets.

This report presents the results of a variety of quantitative and qualitative activities to provide a

comprehensive picture of the state of the DNP degree and DNP graduates in 2022. Topics

include the variation in DNP curricula across a representative sample of DNP programs; how

DNP programs have grown over time and in which concentrations and tracks; who DNP

graduates are and where they are employed; and the perceptions of the DNP degree by DNP

graduates, employers of DNP graduates, and academic leaders.

28

This report shows that there is some confusion about the goals of the DNP degree and the skills

of DNP graduates across key stakeholder groups. However, there is also nearly universal

agreement that DNP graduates bring unique value in areas such as leadership, applying

evidence-based practice, quality improvement, organizational change, and process

improvement. Below, we discuss specific key findings and conclusions based on the findings in

this report.

Conclusions

The number of DNP programs and students enrolled continues to increase. The number of

DNP programs increased every year between 2005 and 2020, to a total of 384 in 2020. The

number of DNP students increased from 6,599 in 2010 to 35,755 in 2020.

Almost all DNP Survey respondents were satisfied with obtaining a DNP degree. Seventy-one

percent of DNP Survey respondents were “extremely satisfied” with their decision to obtain a

DNP degree, and 94% of respondents were either “moderately satisfied” or “extremely

satisfied.” Compared with working as an NP, working as a nurse executive, administrator, or

nurse faculty member was associated with a higher likelihood of being extremely satisfied with

the decision to obtain a DNP degree.

DNP graduates add value. As discussed in the literature and confirmed by most interviewees,

DNP graduates add unique value in areas such as evidence-based practice, organizational

change, quality improvement, and leadership. Many employer interviewees noted that DNP

graduates have an enhanced ability to “look at the big picture” and bring about change at the

organization or system level. This ability is being recognized increasingly by DNP employers

such as hospitals and hospital systems, and there is some evidence that the number of

leadership and executive positions that require or prefer a DNP is growing.

Racial/ethnic and gender diversity continues to increase. The percentage of racial/ethnic

minority students increased from 21% in 2010 to 37% in 2020. The increase in racial/ethnic

diversity is primarily due to a reduction in the number of schools having less than 20% minority

DNP students. DNP gender diversity has increased more slowly, from 9% male students in 2010

to 14% male students in 2020.

Increases in the number of DNP programs and students have occurred in both BSN-to-DNP

and MSN-to-DNP tracks. The numbers of students in BSN-to-DNP and MSN-to-DNP tracks have

increased steadily each year since 2010, and the majority of DNP students were in BSN-to-DNP

tracks in 2020. Between 2010 and 2020, the number of BSN-to-DNP students increased from

29

1,906 to 22,574, while the number of MSN-to-DNP students increased from 5,149 to 16,956.

The result Is that BSN-to-DNP students now make up the majority of DNP students, increasing

from 27% of the total in 2010 to 57% in 2020. Since 2008, nearly all of the increase in the

number of DNP programs has been in schools with both tracks.

BSN-to-DNP and MSN-to-DNP tracks have different concentrations. BSN-to-DNP tracks are

focused almost entirely on educating APRNs, while MSN-to-DNP tracks offer a wide variety of

concentrations, many focused on leadership and executive education. In our curriculum review

sample, about 30% of MSN-to-DNP tracks offered an APRN-specific concentration, while 40%

did not offer any specific concentrations, and the other 30% offered concentrations focused on

developing executive or leadership skills. In 2020, about 92% of MSN-to-DNP students in an

APRN concentration were in an NP program. In contrast, only about 78% of BSN-to-DNP

students in an APRN concentration were in an NP concentration, and nearly all the rest were in

a CRNA concentration, explained in part by the requirement that CRNAs have a DNP degree.

DNP graduates work in a variety of positions. DNP graduates are employed in a variety of

positions. Respondents to the DNP Survey were primarily employed as NPs (18%), CRNAs (7%),

CNMs (8%), CNSs (<1%), nurse executives (10%), administrators (11%), nurse faculty (23%), and

in other positions (20%). DNP graduates, employers, and academic leaders noted that the

relatively large number of DNP graduates working as faculty may be due to the fact that most

faculty positions require a nursing doctorate, and that the DNP is preferred over the PhD by

those who want to gain expertise in systems change, implementation, and leadership. Also,

some DNP graduates stated that they feel more valued in an academic setting than in a hospital

setting.

The majority of DNP programs are mostly online. Sixty-six percent of DNP programs in 2020

were mostly online, and about 72% of DNP Survey respondents attended mostly online

programs.

No evidence was found of lower quality outcomes connected to online DNP programs. We did

not find evidence that, for DNP Survey respondents, the program delivery method (online vs.

in-person) was associated with DNP skillsets, satisfaction, or their preparation to perform

various activities. Several employers perceived lower quality and rigor of online DNP programs

compared to in-person DNP programs.

DNP graduates working in administrative, executive, and faculty roles perceive higher value

from the DNP. DNP graduates who work as administrators, nurse executives, and nurse faculty

reported that they were more likely than those working as NPs to perceive their skills in

30

organizational change, quality improvement, and policy advocacy as having improved as a

result of the DNP degree. In addition, DNP graduates perceive obtaining the DNP as having had

a large impact on how their employer assesses their value, the extent to which they realize

their professional goals, their responsibilities at their place of employment, and the respect

they receive from colleagues. In most cases, these associations were larger for administrators

and nurse executives than for nurse faculty. Also, DNP Survey respondents who graduated from

an MSN-to-DNP track reported that their skills in organizational change, quality improvement,

and policy advocacy improved more than respondents who graduated from any other DNP

track.

Data do not currently exist to carry out DNP outcome studies. Data specifically on outcomes

attributed to DNP graduates versus other kinds of nurses and healthcare professionals are

required for performing DNP outcome studies. Still, our interviews with hospitals and

healthcare systems revealed that the necessary data are not currently collected. The RAND

study published in 2015 called for AACN to conduct an outcomes study to better understand

the impact of DNP graduates on patient care. We asked employers whether they collected

these data and, although they universally agreed that the data would be valuable, data sets

that would allow an outcomes study specifically on DNP graduates are not currently available.

Isolating differences in the clinical skills of MSN and DNP graduates is difficult. Almost all

graduates and employers interviewed could not identify a difference in how MSN and DNP

graduates provide direct patient care.

Uncertainty remains concerning the skills and value of DNP graduates. Despite an

understanding of the unique skills of DNP graduates by most employers, others do not

understand the value of the DNP and which roles they should fill. Some employers stated that

they were uncertain what skills DNP graduates have and what roles to put them in given

differences in the rigor, curricula, and content of DNP programs (regarding the DNP project, in

particular) and a substantial difference in the clinical experience of BSN-to-DNP and MSN-to-

DNP graduates.

Stakeholders have numerous suggestions for how to improve DNP curricula. All stakeholders

interviewed had a wide range of suggestions for how to change and improve DNP curricula.

While nearly all stakeholders agreed that DNP curricula and rigor should be standardized to

some extent, including through the assistance of accrediting bodies, they offered diverse ideas

on what should be added to DNP curricula. Suggestions included more clinical hours; post-DNP

programs similar to residencies; publication requirements for DNP projects; more leadership

and business classes (including in finance and statistics); more education on policy and

31

legislation; pedagogical training for faculty positions; and social media training. Stakeholders

held a wide variety of opinions on the skills and education they want DNP graduates to have.

Recommendations

1. Clarify the goals and identity of the DNP degree.

To increase awareness about the goals and identity of the DNP degree, clarification should be

provided regarding the purpose of the DNP degree, the roles for DNP graduates, and the skill

sets of DNP graduates.

2. Examine curriculum and rigor of DNP programs and DNP projects.

Examine DNP curricula across schools to identify hallmarks of high-quality, rigorous DNP

programs, and develop a process to encourage other schools to adopt those hallmarks.

3. Engage with APRN certification organizations.

Encourage NP, CNM, and CNS certifying bodies to require the DNP degree as the entry-to-

practice degree, as has been the model for CRNAs and other health professions that

transitioned to doctoral degree requirements.

4. Educate employers about the unique skill sets and value of DNP graduates.

Perform outreach to help employers and prospective students understand the unique

competencies and education of DNP graduates.

5. Develop processes for measuring DNP process and system-level outcome data.

Develop a plan for determining appropriate metrics and processes for collecting process and

system-level outcome data on DNP effectiveness.

6. Conduct research to isolate the impact of DNP graduates on patient and system-level

outcomes.

Once the appropriate process and outcome data have been collected, as described in the

previous recommendation, research should be conducted to isolate the impact of DNP

graduates on patient and system-level outcomes.

7. Encourage academic-practice partnerships.

Continue to enhance academic-practice partnerships to increase clinical precepting placements,

streamline the recruitment of nurses by practice partners, and help educate employers about

DNP competencies.

32

References

American Association of Colleges of Nursing. (2004). AACN position statement on the practice

doctorate in nursing. https://www.aacnnursing.org/Portals/42/News/Position-

Statements/DNP.pdf

American Association of Colleges of Nursing. (2006). The essentials of doctoral education for

advanced nursing practice [Report of the DNP Essentials Task Force].

https://www.aacnnursing.org/Portals/42/Publications/DNPEssentials.pdf

American Association of Colleges of Nursing. (2021a). The essentials: core competencies for

professional nursing education.

https://www.aacnnursing.org/Portals/42/AcademicNursing/pdf/Essentials-2021.pdf

American Association of Colleges of Nursing. (2021b). 2020–2021 enrollment and graduations

in baccalaureate and graduate programs in nursing.

https://www.aacnnursing.org/News-Information/Research-Data-Center/Standard-Data-

Reports

American Association of Colleges of Nursing. (2022). 2021-2022 enrollment and graduations in

baccalaureate and graduate programs in nursing. https://www.aacnnursing.org/News-

Information/Research-Data-Center/Standard-Data-Reports

American Association of Colleges of Nursing. (2005-2021). Institutional Data Services Custom

Reports.

Auerbach, D. I., Martsolf, G. R., Pearson, M. L., Taylor, E. A., Zaydman, M., Muchow, A. N.,

Spetz, J., & Lee, Y. (2015). The DNP by 2015: A study of the institutional, political, and

professional issues that facilitate or impede establishing a post-baccalaureate doctor of

nursing practice program. RAND Corporation.

https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RR730.html

Council on Accreditation of Nurse Anesthesia Educational Programs. (2015). Standards for

accreditation of nurse anesthesia programs practice doctorate.

https://www.coacrna.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/Standards-for-Accreditation-

of-Nurse-Anesthesia-Programs-Practice-Doctorate-revised-October-2019.pdf

33

Kesten, K. S., Moran, K., Beebe, S. L., Conrad, D., Burson, R., Corrigan, C., Manderscheid, A., &

Pohl, E. (2021). Drivers for seeking the doctor of nursing practice degree and

competencies acquired as reported by nurses in practice. Journal of the American

Association of Nurse Practitioners, 34(1), 70–78.

https://doi.org/10.1097/JXX.0000000000000593

McCauley, L. A., Broome, M. E., Frazier, L., Hayes, R., Kurth, A., Musil, C. M., Norman, L. D.,

Rideout, K. H., & Villarruel, A. M. (2020). Doctor of nursing practice (DNP) degree in the

United States: Reflecting, readjusting, and getting back on track. Nursing Outlook, 68(4),

494–503. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.outlook.2020.03.008

Minnick, A. F., Kleinpell, R., & Allison, T. L. (2019). DNP graduates’ labor participation, activities,

and reports of degree contributions. Nursing Outlook, 67(1), 89–100.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.outlook.2018.10.008

National Organization of Nurse Practitioner Faculties. (2019). The Doctor of Nursing Practice

Summit: Update summary from workgroups, August 14, 2019.

https://cdn.ymaws.com/www.nonpf.org/resource/resmgr/dnp/20190814_dnp_summit

_workgrou.pdf