.

\

.

GAO

United States

General Accounting Office

Washington, D.C. 20548

National Security and

International Affairs Division

B-238006

April 11, 1990

The Honorable Bruce A. Morrison

Chairman, Subcommittee on Immigration,

Refugees, and International Law

Committee on the Judiciary

House of Representatives

Dear Mr. Chairman:

This report responds to your request that we evaluate the Immigration

and Naturalization Service’s

(INS)

practices and procedures for adjudi-

cating the cases of Vietnamese refugee applicants. You asked us to (1)

determine why approval rates for Vietnamese refugee applicants were

apparently low, (2) evaluate the quality and consistency of the INS adju-

dication process, and (3) determine if denied refugee applicants’ files

adequately reflected the bases for the examiners’ decisions. We also

determined whether Vietnamese of special interest to the United States

were being interviewed by INS examiners.

Results in Brief

We found that approval rates for Vietnamese refugee applicants

dropped from 100 percent during October 1988 through January 1989

to an average of about 36 percent during the next 6 months beginning in

February 1989. This drop in approval rates occurred because of an

August 1988 decision by the Attorney General that the INS should begin

applying its worldwide guidance for overseas refugee processing in

granting refugee status to Vietnamese applicants. The Attorney Gen-

eral’s decision meant that Vietnamese applicants would no longer be

given an automatic presumption of refugee status simply because they

were living in Vietnam, but would have to assert fear of persecution and

a credible basis for such a fear.

Although the Attorney General’s decision resulted in a drop in the

number of applicants granted refugee status, it did not result in fewer

Vietnamese being offered entry into the United States. Most of those

denied refugee status were offered entry into the United States as Public

Interest Parolees.

We found that the INS refugee adjudication process in Vietnam was gen-

erally thorough and consistent, and performed by experienced and well-

trained examiners. Our review indicated that reasons for denial of refu-

gee status were documented in the files for 87 percent of the cases we

Page 1

GAO/NSIAD90-137 Refugee Program

c

,

B-238006

reviewed and

INS

officials informed us that they have taken action to

assure that subsequent denial decisions are adequately documented.

At the time of our visit to Vietnam in July 1989, many Vietnamese of

special concern to the United States, such as individuals with a previ-

ously close association with the United States who had been detained in

Vietnamese re-education camps, were not being allowed by the

Vietnamese government to be interviewed by INS examiners. However,

an agreement was reached on July 30,1989, between the U.S. and

Vietnamese governments that, beginning in October 1989, INS examiners

could interview such individuals. Department of State and

INS

officials

reported that about 4,830 such individuals were interviewed from Octo-

ber 1989 through January 1990.

The Orderly Departure

The Orderly Departure Program

(ODP)

was established under a 1979

Program

Memorandum of Understanding between the United Nations High Com-

missioner for Refugees and the government of Vietnam to provide a safe

and legal means for people to leave Vietnam rather than clandestinely

by boat. The agreement provides for the departure of immigrants and

refugees for family reunion and humanitarian reasons. In addition to

serving as an orderly, predictable means for those wishing to depart the

country, it also serves to relieve the flow of refugees into first asylum

countries and to save the Vietnamese government the embarrassment of

the uncontrolled illegal exodus of thousands of its citizens.

The Memorandum of Understanding established a selection process for

those authorized to depart Vietnam based on exchanges of lists between

the Vietnamese government and the receiving countries, such as the

United States. Under the process, receiving countries submit to the

Vietnamese government a list of those for whom entry visas would be

granted. Vietnam, in turn, provides the country with a list of those eligi-

ble for exit visas. The United States processes for entry only those

whose names appear on both lists. Individuals whose names appear on

only one of the two lists could be subject to discussions between the

Vietnamese and U.S. governments.

Vietnamese can travel to the United States under the

ODP as

immigrants,

following normal U.S. visa issuance procedures, or as refugees. The

Departments of State and Justice developed three basic categories of

Vietnamese refugees eligible for entry under the

ODP.

Page 2

GAO/NSIAD!M-137 Refugee Program

B-238006

Category I: Family members of persons in the United States not cur-

rently eligible for immigrant visas.

Category II: Former employees of the U.S. government.

Category III:

Other persons closely associated or identified with the

United States’ presence in Vietnam before 1975,’ includ-

ing children of American citizens in Vietnam (Amera-

sians) and their immediate family members.

ODP Application

Procedures

The

ODP

Office at the U.S. Embassy in Bangkok, Thailand, administers

the program, augmented by staff of the International Catholic Migration

Commission. Vietnamese who rely on normal immigration channels must

have a relative in the United States obtain and file immigrant visa peti-

tions

(INS

Form I-130) with their local INS office. Approved petitions,

along with affidavits of relationships and other documents from spon-

soring relatives, are then sent to the

ODP

Office in Bangkok to serve as

immigrant visa case files. Refugee applicants still in Vietnam or their

relatives in the United States may directly petition the

ODP

Office in

Bangkok for refugee status. (Refugees already in the United States may

petition to have their spouses and children join them by filing a Visa 93

petition with their local INS office.)

After receiving the petitions, the

ODP

Office in Bangkok issues Letters of

Introduction to immigrant applicants in Vietnam. This occurs when their

visa eligibility dates become effective or are nearing the effective dates.

Refugee applicants whose case files indicate their eligibility for refugee

status, are also sent Letters of Introduction. A Letter of Introduction is a

document which states that the United States is willing to interview the

individual for possible acceptance and movement through

ODP,

but it is

not a guarantee of approval. Letter of Introduction holders normally

present the documents to the Vietnamese authorities as a preliminary

step in obtaining exit permissions and pre-departure interviews with INS

and State officials.

The

ODP

Office periodically receives from the Vietnamese government

names of people it will allow the

INS

and consular officials in Ho Chi

Minh City (previously Saigon) to interview. Upon receipt of these

names,

ODP

staff in Bangkok review the cases to determine which ones

‘The United States withdrew its remaining military forces and civilian presence from Vietnam after

the fall of the South Vietnamese government in April 1975.

Page 3

GAO,‘NSIALX90-137 Refugee Program

B-238006

are eligible for the

ODP

and what further documents or information are

necessary. Once the files are complete, the

ODP

Office requests the

Vietnamese government to make those applicants available for inter-

view during one of the upcoming interview sessions.

Teams of

INS

and State consular officers travel to Ho Chi Minh City each

month to interview

ODP

applicants made available to them by the

Vietnamese authorities. Those applicants with successful interviews

must also undergo a medical examination. II’ the successful applicants

pass the medical examinations, the

ODP

Office in Bangkok transmits final

approval of the applicants’ petitions to the Vietnamese authorities

through the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. Approved

applicants are then booked on a flight to Bangkok by the Vietnamese

government. Amerasians and some refugee applicants are booked on

dir& flights from Vietnam to Manila to attend the English as Second

Language/Cultural Orientation program in the Philippines.

Vietnamese can enter the United States under

ODP

for family reunifica-

tion reasons as immigrants or for humanitarian reasons as refugees.

Those found ineligible for refugee status can also enter as Public Inter-

est Parolees, a humanitarian program implemented in February 1989

under the authority of the Attorney General and available to those able

to prepay their travel expenses and obtain affidavits of support from

sponsors in the United States.

Many of those traveling under the

ODP

are Amerasians and their immedi-

ate families. Public Law 100-202, Section 584, often referred to as the

Amerasian Homecoming Act, provides that Amerasians and their quali-

fying family members leaving Vietnam within a 2-year period after

March 21,1988, are entitled to enter the United States as immigrants,

but are eligible for all benefits oifered refugees, including resettlement

and training benefits. To be eligible for admission under the act, Amera-

sians must have been residing in Vietnam on December 22,1987, the

date the legislation was enacted, and must be able to establish that they

were born in Vietnam after January 1,1962, and before January 1,

1976, and had American citizen fathers.

Fiscal Year 1989

Vietnamese Arrivals

Each year executive branch officials, after consulting with the Congress,

establish refugee admissions allocations for the next fiscal year. The fis-

cal year 1989

ODP

allocation was 22,000 admissions to the United States,

A total of 17,685 Vietnamese refugees were admitted during the fiscal

Page 4

GAO/‘NSIAD-W-137 Refugee F’rogram

,

B-238666

year, a shortfall of 4,315. The fiscal year 1990

ODP

refugee admissions

level has been set at 26,500.

State officials informed us that the fiscal year 1989 admissions shortfall

resulted from fewer former re-education camp detainees and U.S. gov-

ernment

employees being interviewed for refugee status than antici-

pated, and from the unforeseen award of Public Interest Parole to many

who, before February 1989, would have been awarded refugee status.

(Parolees do not count against refugee admission allocations.)

Until February 1989, INS officers conferred refugee status on virtually

all applicants in Vietnam based on the presumption that they

met

the

definition of a refugee as specified in the Immigration-Nationality Act of

1980. However, in February 1989,

INS

began to apply worldwide stan-

dards for refugee determination. This change resulted from an August

1988 decision by the Attorney General that INS should uniformly apply

the regulations of existing statutes regulating immigration processing.

The change meant that INS would no longer work from a presumption

that Vietnamese applying for

ODP

meet the definition of refugee. The

decision also provided that those not granted refugee status could be

considered for entry to the United States under the Attorney General’s

parole authority.

Refugee Denial Rates

The Attorney General’s decision to adjudicate refugee cases strictly in

Do Not Reflect a Drop

accordance with

INS

Worldwide Guidance for Overseas Refugees

P

recessing resulted in a sharp drop in the number of applicants granted

in ODP Activity

refugee status. However, most of those denied refugee status did not

originally apply to

ODP

as refugees. Most would have been immigrant

visa applicants but their visa petitions were not yet current, and were

considered for refugee status for family reunification reasons. Those

denied refugee status were offered Public Interest Parole.2 Thus, simply

because refugee denial rates were up does not mean

that

fewer

Vietnamese were leaving Vietnam under the

ODP.

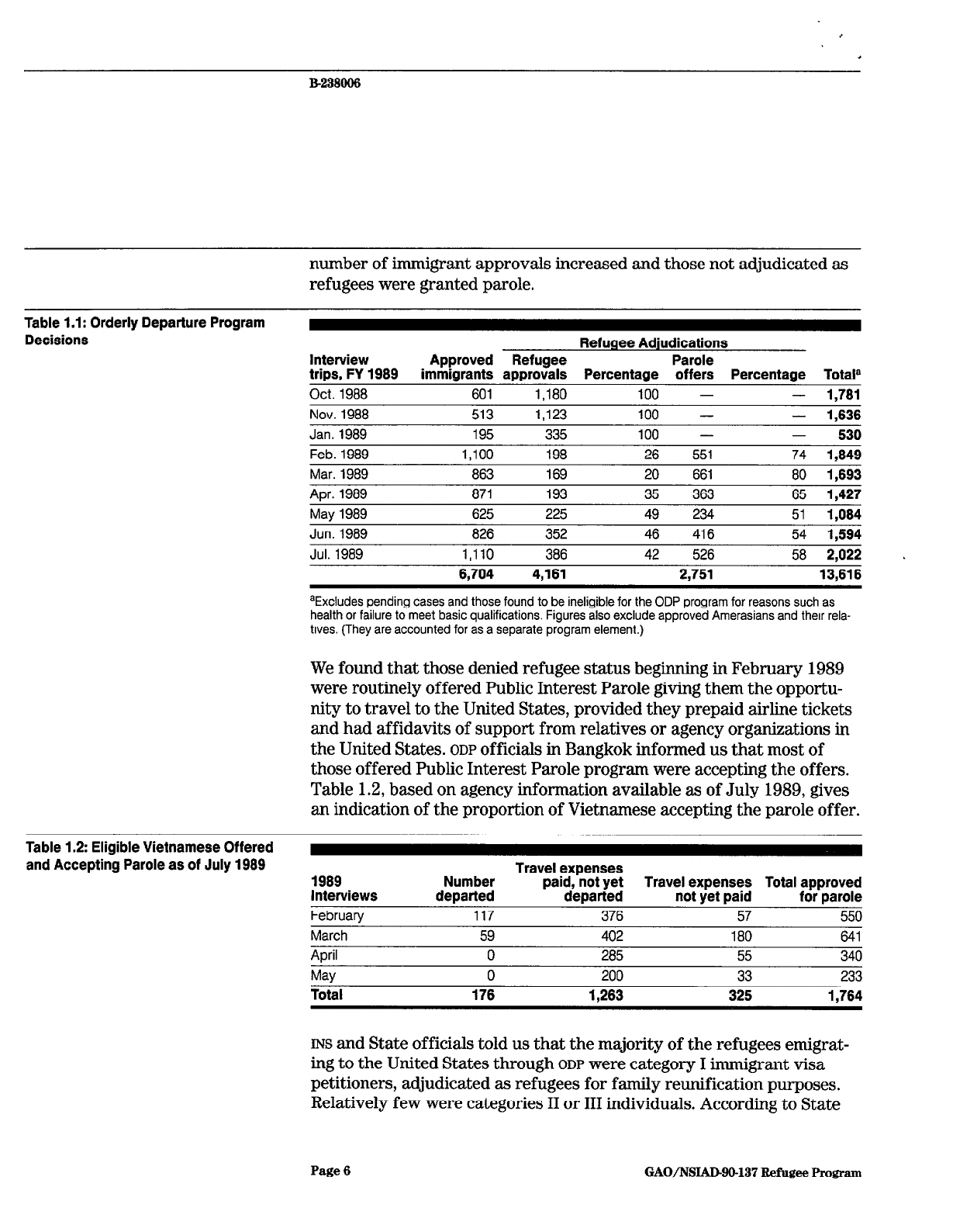

While no refugee applicants were denied refugee status during INS’ first

three interview trips in fiscal year 1989, the denial rate averaged 63.6

percent during the next six trips. However, our analysis of agency data,

as reflected in Table 1.1, shows that during this latter period the

2Those offered parole are primarily the sons and daughters of immigrants and former w-education

camp detainees holding current visa petitions, according to State Department officials.

Page 6

GAO/‘NSIAD96-137 Eefngee Program

,

B-238666

number of immigrant approvals increased and those not adjudicated as

refugees were granted parole.

Table 1.1: Orderly Departure Program

Decisions

Refugee Adjudications

Interview

Approved Refugee Parole

trips, FY 1989

immigrants approvals Percentage offers Percentage TotaP

Oct. 1988 601

1,180

100 -

-

1,781

Nov.1988

513

1.123 100 -

-

1.838

Jan. 1989 195 335

100 - - 530

Feb.1989 1,100 198

26 551 74 1,849

Mar.1989 863 169

20 661 80

1.893

Apr.1989 871 193

35 363 65 1,427

May1989 625 225

49 234 51 1,084

Jun.1989 826 352

46 416 54

1,594

Jul. 1989 1,110 386

42 526 58 2,022 .

8,704 4,181

2,751 13,818

aExcludes pending cases and those found to be ineligible for the ODP program for reasons such as

health or failure to meet basic qualifications. Figures also exclude approved Amerasians and therr rela-

tives. (They are accounted for as a separate program element.)

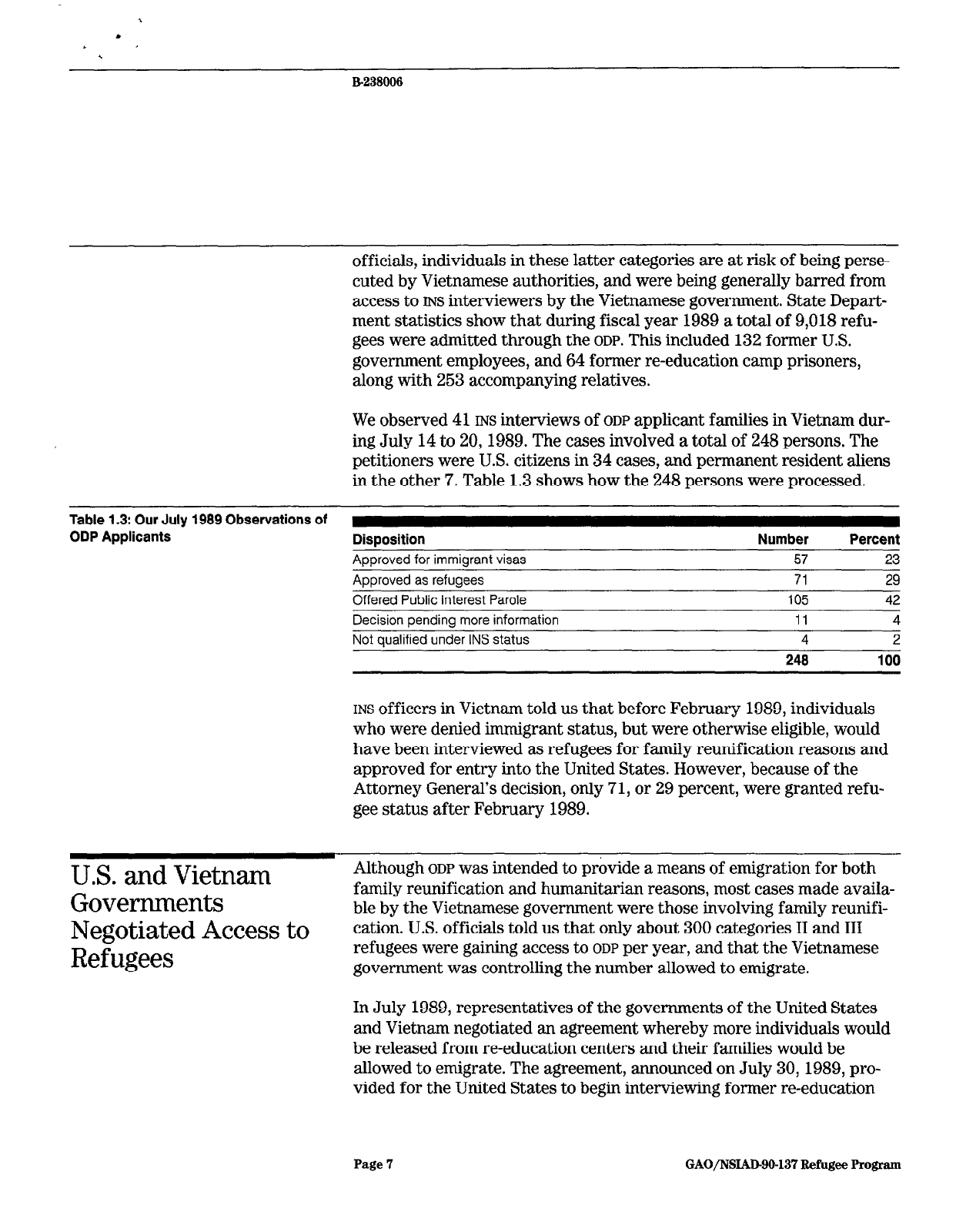

We found that those denied refugee status beginning in February 1989

were routinely offered Public Interest Parole giving them the opportu-

nity to travel to the United States, provided they prepaid airline tickets

and had affidavits of support from relatives or agency organizations in

the United States.

ODP

officials in Bangkok informed us that most of

those offered Public Interest Parole program were accepting the offers.

Table 1.2, based on agency information available as of July 1989, gives

an indication of the proportion of Vietnamese accepting the parole offer.

Table 1.2: Eligible Vietnamese Offered

and Accepting Parole as of July 1989

1989

Interviews

February

March

April

Travel expenses

Number

paid, not yet

departed

departed

Travel expenses Total approved

not yet paid

for parole

117

376 57 550

59

402 180 641

0

285 55 340

May

0

200 33 233

Total 178

1.283

325

1.784

INS and State officials told us that the majority of the refugees emigrat-

ing to the United States through

ODP

were category I immigrant visa

petitioners, adjudicated as refugees for family reunification purposes.

Relatively few were categories II or III individuals. According to State

Page 6

GAO/NSL4IWO-137 Refugee Program

B-238006

officials, individuals in these latter categories are at risk of being perse-

cuted by Vietnamese authorities, and were being generally barred from

access to INS interviewers by the Vietnamese government. State Depart-

ment statistics show that during fiscal year 1989 a total of 9,018 refu-

gees were admitted through the

ODP.

This included 132 former U.S.

government employees, and 64 former re-education camp prisoners,

along with 253 accompanying relatives.

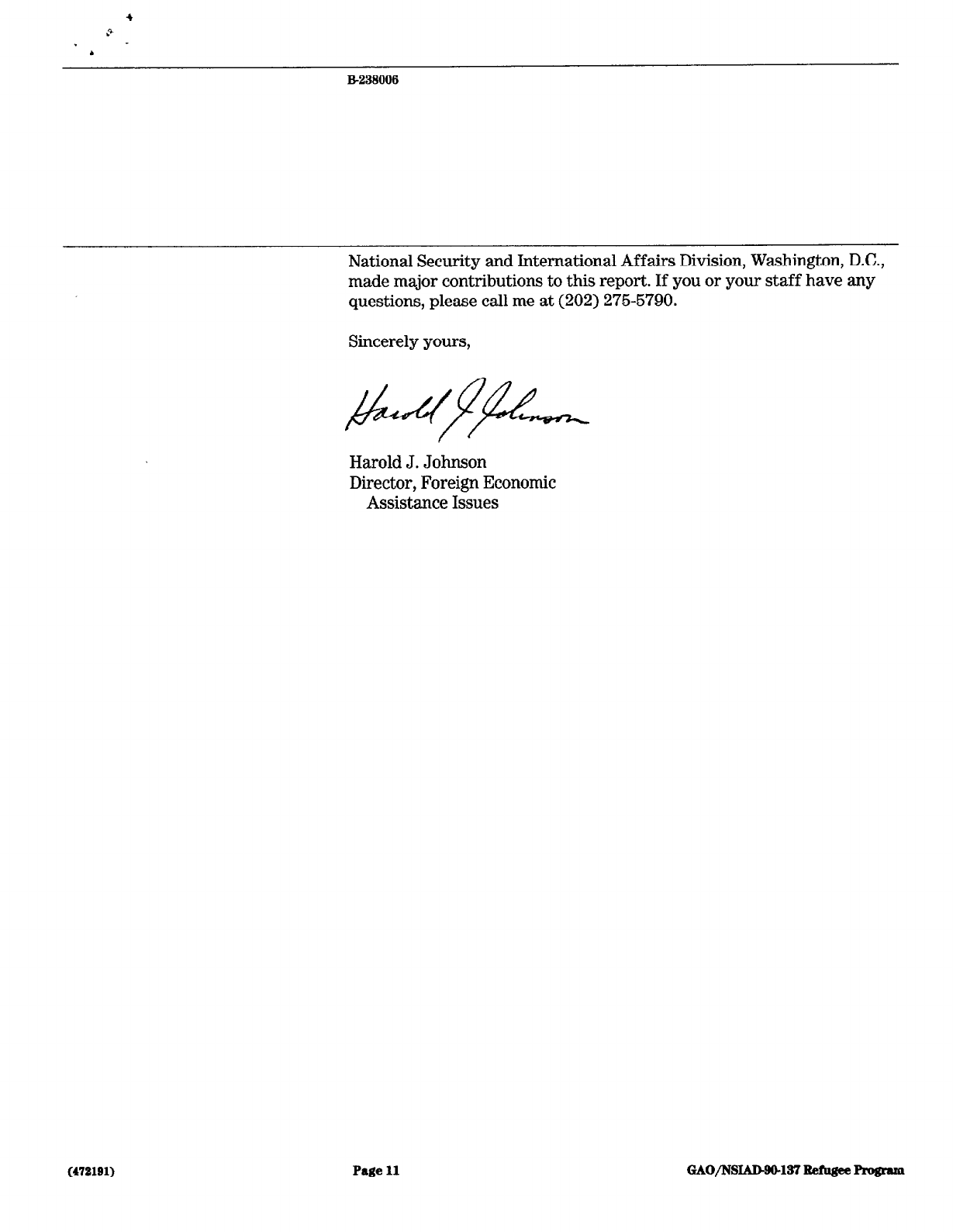

We observed 41 INS interviews of

ODP

applicant families in Vietnam dur-

ing July 14 to 20,1989. The cases involved a total of 248 persons. The

petitioners were U.S. citizens in 34 cases, and permanent resident aliens

in the other 7. Table 1.3 shows how the 248 persons were processed.

Table 1.3: Our July 1989 Observations of

ODP Applicants

Disposition Number

Percent

Approved for immigrant visas 57

23

Approved as refugees 71

29

Offered Public Interest Parole

105 42

Decision pending more information

11

4

Not qualified under INS status

4

2

248

100

INS

officers in Vietnam told us that before February 1989, individuals

who were denied immigrant status, but were otherwise eligible, would

have been interviewed as refugees for family reunification reasons and

approved for entry into the United States. However, because of the

Attorney General’s decision, only 71, or 29 percent, were granted refu-

gee status after February 1989.

U.S. and Vietnam

Although

ODP

was intended to provide a means of emigration for both

Governrrtents

family reunification and humanitarian reasons, most cases made availa-

ble by the Vietnamese government were those involving family reunifi-

Negotiated Access to

cation. U.S. officials told us that only about 300 categories II and III

Refugees

refugees were gaining access to

ODP

per year, and that the Vietnamese

government was controlling the number allowed to emigrate.

In July 1989, representatives of the governments of the United States

and Vietnam negotiated an agreement whereby more individuals would

be released from re-education centers and their families would be

allowed to emigrate. The agreement, announced on July 30,1989, pro-

vided for the United States to begin interviewing former re-education

Page 7 GAO/NSLAD-90-137 Refugee Program

.

B-238006

center detainees in October 1989. The agreement set a goal of 3,000 for-

mer detainees and dependents to be interviewed before the end of 1989,

and 12,000 more were expected to be interviewed in 1990.

INS officers confirmed that the October 1989

ODP

interview team began

interviewing former detainees in Vietnam in accordance with

the

July

30 agreement. State Department’s Bureau of Refugee Programs figures

indicate that officials interviewed a total of 4,830 former detainees from

October 1989 through January 1990, thus

meeting

initial expectations.

Bureau of Refugee Programs and INS officials told

us that the

program

,

was proceeding smoothly.

The Bush administration has established a fiscal year 1990 admissions

ceiling of 26,500 for those departing Vietnam under

ODP.

This is an

increase of 4,500 over the fiscal year 1989 allocation of 22,000, due

partly to expected increased accessions of former re-education detainees

and their accompanying relatives.

ODP Applicant

The

ODP

interview team we accompanied to Vietnam in July 1989

Processing Thorough

included three officers from INS’ District Office in Bangkok.3 We inter-

viewed the officers to determine their experience, training, and qualifi-

and Consistent, but

cations for adjudicating

ODP

refugee cases, and observed a total of 41

Decisions Not Always

cases to determine if the officers asked similar questions and used simi-

Documented

lar bases for adjudicating their assigned cases.

Each officer was trained and experienced in refugee processing proce-

dures, and knowledgeable about country conditions in Vietnam and

throughout Southeast Asia. The officers averaged 18 years of service

with INS, each had previous interview team assignments in Vietnam, and

had recently received refresher training in Bangkok, including State

Department briefings on country conditions in Vietnam and Southeast

Asia.

The officers uniformly applied INS and

ODP

guidelines in adjudicating

their cases. Each asked a variety of questions designed to elicit informa-

tion about family relationships, living conditions, work and educational

circumstances, government policies and practices, and the individuals’

statements on, or fears of, persecution. In addition, we observed various

3A fourth accompanying senior examiner, assigned to INS Headquarters and on an ODP familiariza-

tion visit, adjudicated some cases. The officer was an experienced examiner, with prior refugee adju-

dication experience in Europe and Thailand.

Page8

GAO/NSIAD-90-137RefugeeProgram

B238996

instances of the officers conferring with each other on complex or diffi-

cult cases.

INS Headquarters and District Office instructions, as well as

ODP

Office

guidance, require the examiners to document the rationale for their deci-

sions to deny refugee status. Our sample of 364 case files of applicants

denied refugee status between February and July 1989 revealed that,

while most contained sufficient explanations of the examiners’ deci-

sions, some did not. For the case files in our study, approximately 87

percent contained adequate bases for the decisions.

Our study showed that 73 percent of the denied applicants were cate-

gory I immigrant visa petitioners adjudicated as refugees, another 26

percent were Amerasians or their close relatives. Only one denied appli-

cant was a pre-1975 U.S. government employee, which reinforced INS

officers’ statements to us that virtually no categories II or III refugee

applicants were denied refugees status.

Senior

INS

officials informed us that in light of the number of denied case

files without sufficient rationale for the decisions, the Bangkok District

Office has begun sampling

ODP

interview teams’ case files upon their

return from Vietnam. We were told that the limited sampling procedure

was designed as a quality assurance mechanism to ensure that all denied

case files contain adequate explanations of the decisions.

Conclusions

The high refugee denial rates in the

ODP

are not an accurate indicator of

the treatment of refugees under the program. INS refugee approvals, or

denials with accompanying offers of parole, are primarily mechanisms

for resettling Vietnamese families unable to travel under immigrant

visas. Almost none of those applying for resettlement on the basis of

refugee characteristics were being denied refugee status.

Until recently, few former re-education camp detainees and others of

special interest to the United States, who may be eligible for refugee

status, were given access to INS interviewers by Vietnamese authorities.

The Vietnamese government agreed in July 1989 to allow former

re-education detainee and their families to emigrate to the United States.

INS

officers began interviewing former detainees in October 1989, and

the program appears to be proceeding smoothly.

Page 9

GAO,‘NSIAD9@137 Refugee Program

,

‘

EL238006

INS officials from the Bangkok District Office were experienced and well-

trained, and were processing

ODP

cases in Vietnam thoroughly and con-

sistently at the time of our visit. Refugee applicants’ case files contained

the bases for the examiners’ decisions in 87 percent of the eases we

reviewed, and the INS District office has implemented a file review pro-

cess, which should further ensure the documentation of denial decisions

by its examiners.

Scope and

Methodology

We analyzed available agency data on the

ODP

decisions made during

nine trips to Vietnam, covering October 24, 1988 to July 21,1989, to

determine whether approval rates for Vietnamese refugee applicants

had dropped during 1989, and if so, why the decline had occurred and

whether those denied refugee status were also being denied entry into

the United States.

To evaluate the quality and consistency of adjudication processes for

Vietnamese immigrants and refugees, we reviewed pertinent legislation

and regulations; interviewed officials and reviewed records at INS and

Department of State in Washington, D.C., the U.S. Embassy in Bangkok,

Thailand, and in Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam. We analyzed 364 denied

refugee case files to determine whether the reasons for denials of refu-

gee status were well documented. In July 1989, we had firsthand obser-

vations of the program in Vietnam. We determined the nature and

extent of the background and experience of involved INS examiners. We

obtained information on access to Vietnamese of special interest to the

U.S. government through discussions with State Department, INS, and

embassy officials. Our review was performed between June 1989 and

December 1989, and was conducted in accordance with generally

accepted government auditing standards.

We did not obtain written comments on this report from agency offi-

cials. However, we obtained their oral comments and incorporated them

as appropriate in the text.

We are sending copies of this report to the Chairmen, House and Senate

Committees on the Judiciary; the Attorney General; the Commissioner of

INS; and the Director, Office of Management and Budget. We will also

make copies available to others upon request.

GAO

staff members Harvey J. Finberg, Computer Systems Analyst, and

Leroy W. Richardson and David R. Martin, Assistant Directors in the

Page10

GAO/'NSIAD-90-137RefkgeeProgram

B-238006

(472191)

National Security and International Affairs Division, Washington, D.C.,

made major contributions to this report. If you or your staff have any

questions, please call me at (202) 275-5790.

Sincerely yours,

Harold J. Johnson

Director, Foreign Economic

Assistance Issues

Page 11

GAO/WXAD4W137 Refagee Program