Many chapters in this volume have highlighted gender dis-

parities in various markers of well-being. ese disparities

are receding in some areas, such as education (Chapter 6),

but remain large in others, such as employment and wages

(Chapter 4), and are even widening in others such as sex ratio

at birth (Chapter 8). As discussed in other chapters, many of

these inequalities are rooted in institutional structures—such

as labour markets—which provide unequal access to men

and women. In this chapter, we focus on cultural norms

and their operation within households. Anyone who has

seen burqa-clad girls zooming around on two wheelers in

Ahmedabad, or women in ghunghat working on construc-

tion sites knows that tradition is not destiny. However, it

is also important to note that gender inequality emerges

within a context of cultural norms. Marriage and kinship

patterns provide a background against which parents are

faced with heart wrenching choices between sons and

daughters, resulting in the preferential treatment of boys.

is chapter provides empirical information regarding the

behaviours and norms that shape the narrative of women’s

lives.

TRADITION AND CONTOURS OF

WOMEN’S LIVES

Marriage and kinship patterns aff ect both men’s and women’s

lives. As a vast number of sociological and anthropological

studies attest, marriage and kinship practices in India vary

tremendously between regions, social classes, and commu-

nities. But these myriad variations notwithstanding, some

broad patterns shape women’s lives. ese patterns are iden-

tifi ed below.

Early and Arranged Marriage

In spite of rising levels of education and images of growing

westernization in India, love marriages remain a rarity, even

among urban educated elite. India is unusual, even among

developing countries, in that marriage in India is almost

universal and most men and women marry at a relatively

young age.

1

As Table A.10.1a indicates, even though the legal

minimum age at marriage for women is 18, 60 per cent are

married before that age. e average age at marriage ranges

between 16 and 23 years among ever-married women 25

years and older in the IHDS sample.

2

Women in poor and less

educated households often marry around the age of 16, but

even women from better off and more educated households

marry around age 19–20. e average age at marriage is 19.3

years in metropolitan cities and is considerably lower in less

developed villages. Regional diff erences in age at marriage

are striking, with an average age at marriage of 15–17 years

in central states like Bihar and Madhya Pradesh, and a higher

average age at marriage in Punjab and Himachal Pradesh, as

well as in the southern states (see Table A.10.1b).

Gender and Family Dynamics

10

1

For data on age at marriage in other developing countries, see Mensch, Singh, and Casterline (2005).

2

We exclude ever-married women under age 25 from this calculation. If we were to include younger cohorts, then women who marry at young ages

would be included and those who delay marriage would not. us, including younger cohorts would bias the sample towards women who marry at young

ages, such as those in rural areas and those with low levels of education.

149

Not surprisingly, many of the young brides have not

attained puberty at the time of marriage. In Bihar and

Rajasthan, the states with the earliest age at marriage, around

25 per cent of the girls had not attained puberty at the time

of marriage. At the same time, a focus on the formal age at

marriage may well be mistaken in a context in which early

marriage is not synonymous with an early age at entry into a

sexual union.

As documented by many anthropologists, early marriage

is often associated with a delay in consummation in which

the bride remains with her parents until a formal gauna or

bidai ceremony occurs. States with a very early age at formal

marriage also follow the custom of a gap of a year or more

between marriage and gauna. Tables A.10.1a and A.10.1b

show the waiting period of at least six months following the

wedding before cohabitation. About 75 per cent of women

in Bihar and 88 per cent of women in Rajasthan waited six

months or more to begin living with their husbands. As

Figure 10.1 shows, this waiting period is often associated

with the relative youth and immaturity of the bride, and

tends to decline as the age at marriage increases.

Regardless of the age at which formal marriage occurs,

however, the average age at which cohabitation, or eff ective

marriage, begins is about 18–19 years in most states, and

is even younger in some. Table A.10.1a also suggests a very

small increase in age at marriage. e average age at mar-

riage has changed only marginally across cohorts, although

the proportion of women marrying before puberty has

decreased.

Most marriages are arranged. Less than 5 per cent of

women in the IHDS sample said they chose their husbands

independent of their parents. e rest reported a variety of

arrangements through which their families made marriage

decisions. Most reported very limited contact with their

husbands before marriage. Sixty nine per cent met their

husbands on the day of the wedding or shortly before, and an

additional 9 per cent knew their husbands for a month before

the wedding. Only 23 per cent knew their husbands for more

than a month when they married. Although educated women

are more likely to have a longer acquaintance with their

husbands, a long period of acquaintance is not normative,

even among these women as Figure 10.2 indicates.

3

Yet, in spite of the popular stereotype of women being

coerced into arranged marriages, about 62 per cent felt

that their wishes were considered in the selection of their

partners. Not surprisingly, women from educated families

and urban women are given more of a say. Women in Bihar

and Rajasthan, states with the lowest age at marriage, are

the least likely to report having a say in the selection of

their husbands. Women who have some say in choosing

the groom are also likely to have a longer acquaintance with

their prospective partners. Among women who reported not

having a say in the choice of spouse, only 10 per cent met

their husbands at least a month before the wedding. Among

women who had a say, about 30 per cent claimed such an

acquaintance.

Centrality of Childbearing in Women’s Lives

Fertility in India has been declining steadily. As measured

by the NFHS, the total fertility rate dropped from 3.7 in

1992–3 to 2.7 in 2005–6. Still, childbearing remains central

to women’s lives: as measured by IHDS, 97 per cent women

aged 25 and older had at least one child. Tables A.10.1a and

A.10.1b also document diff erences in fertility across diff erent

social groups and across states. In these tables, we focus on

women aged 40–9 who have largely completed childbearing.

Figure 10.1 Gap Between Marriage and Cohabitation by Age at Marriage

Source: IHDS 2004–5 data.

3

It is important to note that because our data was collected from women only, much of this discussion has focused on women’s choices, and lack

thereof. However, much of this discussion also applies to males who have little opportunity to get to know their wives.

150

On an average, women in this age group had 3.85 children

in their reproductive years.

4

Educated women and women

in urban areas have fewer children than women with lesser

education and those in rural areas. Interestingly, although

fertility is lower in richer families than poorer ones, this

diff erence is far smaller than that associated with women’s

education. Women in Kerala and Tamil Nadu have the

smallest family size, and those in Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, and

Rajasthan have the largest.

Table A.10.1a also documents that the mean age at

fi rst birth for women aged 25 years and older is 20.6 years.

e median age at fi rst birth is slightly lower, at 20.08. A

comparison of age at marriage and age at fi rst birth presents

an interesting paradox.

e variation in age at marriage

is not consistently refl ected in age at fi rst birth.

5

ere

is considerable variation in the mean age at fi rst marriage

between diff erent states and diff erent social groups. e

diff erence in mean age at marriage between Bihar (15.2)

and Kerala (20.9) is more than four years. Yet, the diff erence

in age at fi rst birth is much smaller: 20.7 for Bihar and

22.7 for Kerala. Similarly, although the diff erence between

uneducated and college educated women is about 6.5 years

for age at marriage, it is only 4.5 years for age at fi rst birth.

A variety of factors play a role in the smaller diff erence by

education for age at fi rst birth, including the low fecundity of

adolescent girls. However, perhaps the most important factor

is one we noted earlier. Marriage is not synonymous with

entry into sexual union, and young brides are much more

likely to delay cohabitation than older brides, reducing the

risk of pregnancy. is delay also poses an interesting policy

dilemma. e prevention of child marriage is important for

the well-being of adolescent girls and may lead to increased

education, but its fertility impact may be small until a

substantial delay in age at marriage is attained.

Women’s Natal Family Ties and

Social Support Networks

Although emotional bonds between parents and daughters

endure over time and space, wedding rituals like bidai and

crossing over the threshold refl ect realities of most women’s

lives. Marriage is a transition point at which women are

expected to leave the familiar environment and the traditions

of their parents’ homes and assimilate into a new family,

often with a relatively abrupt break.

We asked women about their immediate post-marriage

residence, and an overwhelming majority (more than 90

per cent) reported that they lived with their parents-in-law.

e north Indian custom of village exogamy ensures that

women marry outside their own village because all men

from their own village, or even a set of closely related villages,

are considered close kin. Even urban families may be reluctant

to marry their daughters into families originating from

villages close to their native place. Consequently, as Table

A.10.2b indicates, in states like Haryana and Uttar Pradesh,

less than 10 per cent of women marry within their own

towns or villages. While marrying within the natal village is

permitted in south India and marriage with a close cousin

or uncle is often preferred, the number of suitable matches

4

e NFHS-III documents 4.0 children for women of this age group (IIPS 2007).

5

is paradox was fi rst noted by Basu (1993).

Figure 10.2 Length of Acquaintance Before Marriage by Education

Source: IHDS 2004–5 data.

151

within a close community is limited. Consequently, even in

south India, the majority of women marry outside their own

village and circle of close relatives.

Within-family marriages are particularly prevalent

among Muslims. About 24 per cent of the Muslim women

marry within the family, compared with less than 12 per cent

among the other social groups. Unlike many other aspects

of social life, marriage traditions have little relationship with

the socioeconomic standing of the family, and regional dif-

ferences predominate. In Haryana, Uttar Pradesh, Rajasthan,

and Madhya Pradesh, around 10 per cent of women marry

within their own village or town, and a negligible percent-

age marry their uncles or cousins. In contrast, in Kerala

and Tamil Nadu, more than 25 per cent marry within their

own village or town, and 23–30 per cent of women in

Maharashtra, Andhra Pradesh, Karnataka, and Tamil Nadu

marry a cousin or an uncle.

Exogamy is associated with an abrupt transition in

women’s lives. Once married, many women fi nd themselves

cut off from the social support networks off ered by their

natal families. Although tradition dictates that a daughter

visit her parents or brothers for certain festivals such as

Raksha Bandhan, Makar Sankranti, or Durga Puja, many

women are unable to visit regularly. Many reasons prevent

these visits. For example, sometimes the natal family is far

away and women are not allowed to travel unaccompa-

nied. Sometimes women are needed to cook and care for

the elderly, sometimes demands of child care and children’s

education restricts their travel, and a minority of women

have no close family left. But regardless of the reason, when

a woman barely manages to visit her family once a year or

even less, she is cut off from a potential source of social

support. Table A.10.2b indicates that women’s visits with

their families are most restricted in areas like Delhi, Uttar

Pradesh, Bihar, and Jharkhand. Additionally, women in

many states are married at such a distance from their natal

families that many cannot visit their families and return in

a day. Poor transportation networks may also play a role in

women’s isolation.

e location of the most recent childbirth provides

an interesting marker of women’s contact with their natal

families. In some communities, women return to their natal

family for the delivery. In others, delivery occurs in the

husband’s home. Over all, about 20 per cent of all recent

births took place in the natal home. On the whole, returning

to the natal family for delivery seems more common among

upper income groups and more educated families (see Table

A.10.2a). Regional diff erences are also important. Since

68 per cent of women delivering at the natal home either

deliver in a hospital, or are attended to by a trained doctor

or nurse as compared to 53 per cent for births in the marital

home, delivery at the natal home is an important marker of

women’s well-being. It is also important to remember this

dislocation when designing prenatal care systems.

THE BELOVED BURDEN: A PARENTAL DILEMMA

In previous chapters, we noted that the discrimination

against daughters results in higher mortality of girls and

lower educational expenditures for daughters. We would be

remiss if we did not point out some of the factors motivating

parents into these grievous choices. In a primarily patriarchal

society, a variety of factors combine to increase the fi nancial

burdens of raising a daughter and reduce the daughter’s ability

to provide fi nancial and physical support to their parents.

Dowry and Wedding Expenses

Activist groups often implicate dowry demands in increased

domestic violence and the oppression of women. It has also

been reported that dowry infl ation belies progress on many

other fronts, such as improvements in women’s education.

Wedding expenses and dowries are also associated with long-

term debt for households. e IHDS found that more than

15 per cent of the loans that households acquired are directly

related to marriage expenses. Nationwide data on dowries

or wedding expenses are notoriously diffi cult to collect,

particularly in view of the Dowry Prohibition Act. In large-

scale surveys, most respondents tend to be hesitant about

reporting illegal activities within their own family, but are

comfortable enough to provide general information about

the practices within their community, or for families with

similar social and economic standing within their jati. While

we realize that this general information can be somewhat

infl ated, it provides an interesting marker of diff erences in

expectations across social and economic groups. We focus on

the following dimensions of marriage-related expenses:

(1) wedding expenses for the bride’s and the groom’s

families,

(2) types of gifts given to a daughter at the wedding, and,

(3) cash gifts, or what is commonly referred to as dowry.

e results in Table A.10.3a are interesting. While wedding

expenses for bride’s family are uniformly higher than those

for the groom’s family (on average, about 50 per cent higher),

the expenses for the groom’s family are not trivial. e IHDS

shows a nationwide average wedding expenditure of about

Rs 60,000 for the groom’s family and about Rs 90,000 for

the bride’s family. Even among households in the lowest

income quintile, the expenditure for the groom’s family is

about Rs 43,000, while that for the bride’s family is about

Rs 64,000. Among better off households, a girl’s wedding

can cost upwards of Rs 1,50,000. In addition to wedding

expenses, gifts of large consumer durables in dowry seem to

be quite prevalent. When respondents were asked whether

152

a family with a similar socioeconomic standing as them

would frequently give any of four items—a car, motorcycle,

refrigerator, or TV—about 24 per cent responded in the

affi rmative. An additional 43 per cent reported that these

gifts are sometimes given. Even among households in the

lowest income quintile, nearly 16 per cent reported that

these items are frequently given. e comparable fi gure is

about 39 per cent for the top quintile.

Both wedding gifts and wedding expenses are the lowest

among Adivasi households, and among this group, there is

surprisingly little diff erence in wedding expenses for boys and

girls. Given that Adivasis seem to have the most favourable

sex ratio at birth, as recorded in Chapter 8, gender parity in

wedding expenses is an interesting observation. Dowry and

wedding expenses appear to be one area in which education,

upper caste status, and upper income are associated with

less favourable gender outcomes. In the IHDS, cash gifts to

daughters—pure dowry, by many defi nitions—seem to be

relatively small compared with other expenses. e average

amount of cash gift is about Rs 22,000, compared with the

average wedding expense of Rs 92,000 for a daughter.

Regional diff erences in wedding expenses and gifts

reported in Table A.10.3b are striking. On the whole, the

richer states of Punjab and Haryana as well as Karnataka and

Kerala have higher wedding expenses than the poorer states

like Madhya Pradesh and Chhattisgarh, but gifts of large

consumer durables seem to be far more a northern than a

southern phenomenon. In contrast, cash dowries seem to be

the highest in Kerala.

Sons as a Source of Old-age Support

In addition to higher wedding costs for daughters and higher

dowries, low expectations of fi nancial support from daughters

are one of the most important reasons for son preference in

India. e IHDS asked women about their expectations for

old-age support. First they were asked, ‘Who do you expect

to live with in your old age?’ ose who indicated that they

expected to live with their sons were further asked, ‘If your

son does not want to, or is unable to live with you, would

you consider living with a daughter?’ Similar questions were

asked about fi nancial support in old age. e results, shown

in Table A.10.4a, suggest that an overwhelming majority

expect to be supported by sons. Eighty fi ve per cent expect

to live with sons in old age, and 86 per cent expect fi nancial

support. Only 9 per cent expect to live with daughters, and

11 per cent expect fi nancial support from daughters. It is

even more interesting to look at expectations in the event that

sons are not able or willing to care for them. e proportion

of women who do not expect or are unwilling to accept any

support from their daughters is striking. Only 24 per cent

would be willing to live with their daughters, and 30 per cent

are willing to accept fi nancial support from them.

Responses to these questions must be placed in the

cultural context, where traditions dictate that parents give to

a daughter and not take from her. In some areas, even today,

parents are not expected to eat or drink at their daughter’s

home. Moreover, as we have shown in Table A.10.2a, only

14 per cent of women marry within their village or town

and, hence, most are not easily available to provide support

to their parents. All of these considerations are factored

into the responses of the sample women who do not see

receiving support from their daughters as realistic or socially

acceptable. Educated women are marginally more willing to

accept support from their daughters, but on the whole there

is little social class or group variation in this respect.

However, there is substantial regional variation in

parental willingness to rely on daughters, as shown in Table

A.10.4b. is variation is consistent with other dimensions

of gender inequality we noted above. Parents in Haryana,

Rajasthan, Chhattisgarh, and Madhya Pradesh are far less

willing to rely on daughters for any help than are those in the

south. Women in the North-East and Kerala, two regions

with a long matrilineal tradition, were most likely to mention

daughters as a potential source of fi nancial and residential

support. e expectation that sons will support parents in

old age seems consistent with our results in Chapter 9, where

we showed that an overwhelming proportion of the elderly

live with their children (mainly sons) and seem to have few

other sources of income.

FAMILIES DIVIDED: POWER IN THE HOUSEHOLD

While rocking the cradle may well give women a way of

ruling the world, ruling the household seems to be a dif-

ferent matter. e Indian women’s movement and scholarly

research have consistently documented unequal access to

household resources by women and have argued that public

policies need to recognize these inequalities for the provi-

sion of services as well as ownership of resources allocated

via public programmes. We focus on two dimensions of

household dynamics below: women’s access to and control

over household resources, and women’s control over their

own physical space and mobility.

Access to and Control over Resources

One of the most striking features of rural bazaars—particu-

larly in north India—is that they are predominated by male

shoppers. In many families, women rely on men to purchase

day-to-day necessities, as well as medicines and other neces-

sary items. is should reduce the likelihood that women

have cash in hand for such purchases. e IHDS asked

ever-married women aged 15–49 whether they had cash

on hand at the time of interview. e results are shown in

Table A.10.5a. About 83 per cent responded affi rmatively—a

very high proportion, in some ways refl ecting the increasing

153

monetization of the economy. Women were also asked

whether they had any say in buying an expensive item for

household use. Again about 70 per cent replied affi rma-

tively.

While this data refl ect positively on women’s participa-

tion in day-to-day decision making, when it comes to having

control over these decisions or having control over larger

family fi nances, the story is quite diff erent. Only 11 per cent

women are primarily responsible for making decisions regard-

ing large household purchases such as TVs or refrigerators.

In households that have a bank account, only 18 per cent of

women have their names on the account; among households

that have rental or homeownership papers, only 15 per cent

of women have their names on the documents. ese latter

two facets of the household economy, in particular, refl ect

women’s vulnerability in the event of domestic discord or the

husband’s death. e likelihood of the woman being one of

the owners (or the sole owner) of a bank account is greater

for households with higher incomes, higher education, and

urban residence. But this increased likelihood with income,

education, and urban residence is far less marked in women’s

ownership of, or title to the residential property.

Women’s access to and control over resources diff er

substantially across states (see Table A.10.5b) with greater

variation across states than between diff erent social and eco-

nomic categories. Gujarat and Uttarakhand rank the highest

in women’s title to property, followed by Karnataka, Delhi,

and the North-East.

Control over Physical Mobility

One of the biggest challenges Indian women face in

controlling their own lives is a lack of physical mobility

and access to public space, which is caused by several

factors. Cultural norms surrounding female seclusion and

the practice of purdah or ghunghat, familial control over

women’s physical movement, reluctance of women as well

as families to allow them to venture alone into public spaces,

and sexual harassment in public places. e IHDS asked

women whether they practice purdah or ghunghat, whether

they need permission to go to a health centre, and whether

they could go alone to a health centre. For some women,

such as those in Haryana or eastern Uttar Pradesh, ghunghat

may cover the face fully. For others, such as those in Gujarat,

partial covering of the face is more a nod to propriety than a

large impediment. In the all India sample, 73 per cent need

permission from other household members to go to a health

centre, and 34 per cent can’t or won’t go alone to the health

centre. Education and urban residence seem to increase

women’s control over their physical mobility and reduce

seclusion. But even among college graduates, nearly 60

per cent need permission to go to a health centre and

17 per cent cannot or will not go alone (see Table A.10.5a).

Regional diff erences in women’s physical mobility are

vast (see Table A.10.5b). Purdah/ghunghat prevalence is

extremely low (10–12 per cent) in Tamil Nadu, Andhra

Pradesh, and Karnataka. It is very high in Uttar Pradesh,

Bihar, Madhya Pradesh, and Rajasthan, with more than 85

per cent of women practising purdah or ghunghat. In some

states, 40 –60 per cent of women cannot go to a health centre

alone (see Box 10.1).

It is important to note that this is a complex issue. When

women respond to questions about their physical mobility,

they are not refl ecting dissatisfaction with the status quo, but

rather are stating the realities of their lives in the context

of cultural norms governing appropriate behaviour. From a

policy perspective, however, it is important to note women’s

exclusion from public spaces. For example, any restructur-

ing of maternal and child health services must consider that

areas where women are more constrained have a far greater

need of domiciliary services. In areas where women are freer

to travel, it may be possible to concentrate on clinic-based

services.

WOMEN’S STRENGTHS AND VULNERABILITIES

Data on diff erent markers of women’s lives for diverse socio-

economic groups and across regional divides are diffi cult to

come by. While a large-scale survey like the IHDS has many

shortcomings and is often unable to probe to uncover hidden

dimensions of gendered experiences, the kinds of questions

the IHDS addresses are quite unique and provide an interest-

ing snapshot of diff erent dimensions of gender inequality in

India. Documenting these inequalities does not mean that

all Indian women are downtrodden or lack agency. In fact,

we are surprised by the candour and confi dence with which

most women responded to the questions. e IHDS asked

interviewers to rate diff erent dimensions of their interac-

tions with the respondents and found that a vast majority

of women were able to interact very well with the interview-

ers. Eighty one per cent had no diffi culty understanding the

questions, 16 per cent had some diffi culty, and 3 per cent

had a lot of diffi culty.Regarding knowledge of household

expenditures—the most diffi cult set of questions for women

to answer, given their lack of control over resources—only a

small minority had very little knowledge (9 per cent), and

the rest had either fairly good knowledge (41 per cent), or

excellent knowledge (51 per cent).

ese strengths are refl ected in increasing levels of

women’s participation in a variety of government and non-

government activities as well as a growing desire among

women to educate their daughters as much as their sons.

Among the IHDS respondents, 85 per cent would like to

educate their sons and daughters equally, and 3 per cent

would like to give more education to their daughters than

to their sons.

154

However, in spite of these many strengths of individual

women, their vulnerabilities are also striking. Due to ethical

concerns associated with the fear of endangering respondents,

the IHDS did not directly ask about women’s experience

of domestic violence. But to get their sense of general

prevalence of domestic violence in their community, the

IHDS asked whether, under a series of conditions, women

in their communities are usually likely to be beaten by their

husbands. ese hypothetical conditions were, going out

without permission, family not giving expected money (that

is, dowry), neglecting the house or children, and not cooking

properly.

e responses, presented in Table A.10.6a, show a

striking pattern of vulnerability. Nearly 30–40 per cent of the

respondents said that women are usually beaten up for going

out without asking permission, not bringing the expected

dowry, neglecting the house or children, and not cooking

properly. Only 50 per cent do not believe that women in

their communities are beaten for any of these reasons.

Special care is needed in interpreting these results. e

IHDS did not ask about women’s own experiences but rather

those of other women in their communities. Interestingly,

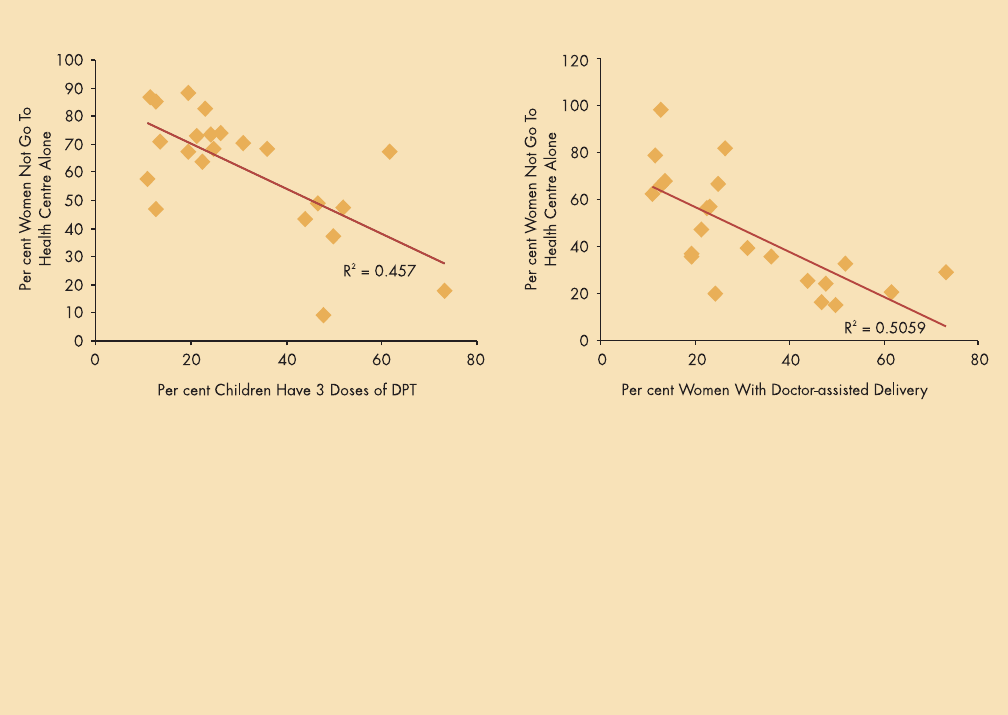

The absence of women from public spaces is striking in many parts of India. Women’s physical mobility is often restricted, and women nd it

dif cult to go alone to places like health centres. Several factors contribute to these limitations: fear of social sanctions, concerns about physical

safety, or discomfort about venturing into unfamiliar terrain. Regardless of the causes of these limitations, they have serious consequences for

women’s ability to obtain government services. If they must wait for permission or need to be accompanied, they may be less likely to visit

health centres than if they are able to venture alone.

About 34 per cent of IHDS sample women claim that they cannot go alone to a health centre. The proportion varies considerably across

states, with 50 per cent or more of women in Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, and Jharkhand stating that they cannot go alone to the health centre,

compared with less than 15 per cent in Maharashtra, Kerala, and Tamil Nadu. The two graphs presented here correlate state-level averages

for women who cannot go to a health centre alone with the completion of three DPT vaccinations for children (from Chapter 8) and doctor-

assisted deliveries (from Chapter 7). These graphs show strong inverse correlations between constrained physical movement and the utilization

of health services. States in which women are able to go to a health centre freely have children with higher levels of vaccination as well as a

higher likelihood of a physician-assisted delivery.

Source: IHDS 2004–5 data.

Box 10.1 Women’s Freedom of Physical Movement and Access to Health Care

education and economic status seem to play an important

role in these expectations. Educated women and women

from upper income groups indicate a lower prevalence of

violence in their communities than women from the more

disadvantaged communities. It is not clear whether this is

because there is actually less violence in communities where

women have a higher education or because educated women

are less likely to report pervasive violence. But in any case,

even among the most educated group 30 per cent of women

indicate that women in their communities are likely to be

beaten for one of the four reasons listed above.

Given low levels of contact with natal families, it seems

highly likely that many women, subject to violence or in

other diffi cult circumstances, may fi nd it diffi cult to get help

from their families. Moreover, low levels of wage employment

and lack of control over housing titles increase the obstacles

to their building an independent life. Regional diff erences in

expectation of domestic violence are large (Table A.10.6b)

with about 70 per cent of the respondents in Assam and the

North-East considering it unlikely that women are beaten

for any reason, while the corresponding percentage is only

about 20 per cent in Bihar and Jharkhand.

155

DISCUSSION

In this chapter, we attempted to provide a context for

the gender diff erences in health, labour force participation,

and (to a lesser extent) education, documented in this report.

Several insights from these results are noteworthy, particularly

as we consider public policy implications.

First, while many gendered outcomes are documented

at the household level, such as a parental preference for

investing in boys’ education, it is important to look beyond

the household for the sources of such behaviour. Most parents

love their daughters as well as sons, but as documented in

Chapter 9, the dependence of the elderly on their children for

social and fi nancial support makes a preference for investing

in sons rather than daughters seem rational. is preference

is strengthened by a cultural context in which daughters

are married outside the village with limited contact with

their natal families after marriage, and where they have few

fi nancial resources and independent decision-making powers

to help their parents.

Second, while education and economic growth have

changed many facets of human development in India, gender

inequality in many areas seems impervious to this change.

Higher income households are more gender unequal in some

cases, such as with regard to dowries. Not even high levels of

education empower women in all spheres. us, we need to

think of alternative strategies for women’s empowerment.

ird, regional diff erences in gender roles and norms are

enormous, and seem to swamp other social and economic

diff erences. ese pose interesting challenges for public

policy. At the most basic level, public policies must be

mindful of these traditions while shaping service delivery.

Health services may need to be delivered into the home in

areas where women’s physical mobility is curtailed. Girls’

schools may increase secondary school enrolment in the

cultural context emphasizing male–female separation, but

may not be necessary in other areas. Policies regarding home

registration and preferential banking schemes could be

expanded to increase women’s control over family home and

bank accounts. However, at a larger level, regional diff erences

off er a vision of alternative social realities that can be used to

spur public discourse. While the Kerala story has often been

told, it is interesting to note that the northeastern states fare

very well on many markers of gender roles described in this

chapter. ese are also the states where the gender gap in

literacy is very low and the sex ratio is more balanced. A focus

on diff erent cultural traditions, with some more favourable

to overall social development than others, makes it possible

to think of indigenous models of women’s empowerment

that do not rely on global norms but that are consistent with

the best of Indian traditions.

HIGHLIGHTS

• The mean age at marriage for women is 17.4 years, with about 60 per cent marrying before the legal age

of 18.

• Women in north India tend to marry outside of their natal village and consequently have less access to social

support networks than their sisters in the south.

• Arranged marriage remains the norm, with less than 5 per cent women selecting their husbands without input from

other family members.

• About 85 per cent women expect to live with their sons in old age; about 9 per cent, with daughters. A similar small

proportion expects nancial help from daughters.

• Many women practice ghunghat or purdah, particularly in central India, and 73 per cent need permission to go to

a health centre.

• Wife beating and domestic violence remain pervasive, with about 50 per cent respondents claiming that women

in their community are often beaten for minor transgressions like going out without permission.

156

Table A.10.1a Marriage and Family Patterns

Per cent Mean Per cent Not Mean Per cent Per cent Per cent Knew Children Age at

Married Age at Cohabiting Age at Marrying With Any Husband Ever Borne First

Before Marriage* Immedi- Cohabiting* Before Say in Before Women Birth*

Age 18* ately* Puberty* Marriage* Marriage* 40–9

All India 60 17.4 51 18.0 16 62 23 3.85 20.6

Woman’s Age

25–9 57 1 7.6 48 18.1 13 64 24 20.0

30–9 61 17.4 50 18.0 15 62 22 20.5

40–9 60 17.3 53 18.0 18 59 23 3.85 21.3

Woman’s Education

Illiterate 75 16.1 64 17.0 20 50 20 4.38 20.1

1–4 Std 65 17.1 45 17.5 14 65 24 3.58 20.0

5–9 Std 53 17.9 40 18.3 11 68 26 3.35 20.6

10–11 Std 32 19.5 33 19.8 6 81 27 2.66 21.8

12 Std Some college 21 20.7 31 20.9 7 84 26 2.43 22.8

College graduate 7 22.6 24 22.8 5 89 29 2.13 24.6

Place of Residence

Metro cities 38 19.3 31 19.5 5 82 26 2.73 21.5

Other urban area 47 18.5 44 19.0 11 71 27 3.46 21.2

More developed village 63 17.2 54 17.8 15 64 25 3.80 20.4

Less developed village 70 16.5 56 17.3 22 49 17 4.42 20.3

Income

Lowest Quintile 70 16.5 56 17.3 19 55 20 4.16 20.4

2nd Quintile 68 16.7 55 17.4 18 58 23 4.07 20.3

3rd Quintile 66 17.0 54 17.7 16 58 22 4.13 20.4

4th Quintile 57 17.6 48 18.2 14 65 24 3.85 20.5

Highest Quintile 42 19.0 40 19.4 10 73 25 3.26 21.5

Social Groups

High Caste Hindu 49 18.4 41 18.9 10 68 20 3.18 21.2

OBC 63 17.2 55 18.0 18 58 23 3.76 20.7

Dalit 71 16.5 55 17.2 17 59 19 4.20 20.0

Adivasi 64 17.1 54 17.7 18 63 29 4.01 20.8

Muslim 61 17.2 50 17.7 16 60 30 5.07 20.1

Other religion 18 20.8 30 21.1 5 84 25 2.77 22.8

Note:*Only calculated for women aged 25 years and above to reduce selectivity due to inclusion of women marrying at very young ages.

Source: IHDS 2004–5 data.

157

Table A.10.1b Marriage and Family Patterns by State

Per cent Mean Per cent not Mean Per cent Per cent Per cent knew Children Age at

Married Age at Cohabiting Age at Marrying With Any Husband Ever Borne First

Before Marriage* Immedi- Cohabiting* Before Say in Before Women Birth*

Age 18* ately* Puberty* Marriage* Marriage* 40–9

All India 60 17.4 51 18.0 16 62 23 3.85 20.6

Jammu and Kashmir 41 18.9 57 19.3 7 43 32 4.63 21.5

Himachal Pradesh 43 18.6 28 18.9 12 64 32 3.61 21.0

Uttarakhand 55 17.6 27 17.8 16 42 13 4.49 21.1

Punjab 28 19.7 37 19.9 2 63 9 3.56 21.7

Haryana 56 17.4 74 18.3 13 65 4 3.59 20.9

Delhi 32 19.2 45 19.6 5 64 28 2.96 21.4

Uttar Pradesh 76 16.1 72 17.5 22 31 9 5.23 20.8

Bihar 86 15.2 75 16.6 26 20 6 4.92 20.7

Jharkhand 64 17.4 54 17.9 13 36 14 4.47 20.2

Rajasthan 79 15.8 88 17.4 25 21 7 4.91 20.2

Chhattisgarh 75 16.0 87 17.1 29 60 17 3.87 20.9

Madhya Pradesh 76 16.0 59 17.0 20 49 6 4.02 20.2

North-East 31 20.6 37 20.8 5 80 59 3.64 22.3

Assam 35 19.5 31 19.6 37 94 26 3.25 21.2

West Bengal 61 17.5 16 17.6 9 76 13 3.36 20.0

Orissa 53 17.9 13 18.0 3 40 19 4.15 20.4

Gujarat 48 18.2 69 18.9 29 93 17 3.31 20.9

Maharashtra, Goa 53 18.1 20 18.2 8 70 17 3.55 20.8

Andhra Pradesh 77 15.9 71 16.5 13 80 49 3.36 19.3

Karnataka 54 17.7 66 18.2 6 90 61 3.42 20.4

Kerala 19 20.9 21 21.0 1 99 40 2.45 22.7

Tamil Nadu 47 18.8 36 19.0 16 87 46 2.90 20.9

Note:*Only calculated for women aged 25 years and above to reduce selectivity due to inclusion of women marrying at very young ages.

Source: IHDS 2004–5 data.

158

Table A.10.2a Women’s Social Support Networks

(per cent)

Per cent Per cent Natal Visit Natal Last

Marrying in Marrying Family Family Delivery

Same Cousins/ Lives 2+ times at Natal

Village/Town Relatives Near by a Year Home

All India 14 12 57 68 21

Woman’s Age

15–19 NA NA 60 81 39

20–4 NA NA 58 77 27

25–9 14 12 56 73 22

30–9 13 11 56 66 14

40–9 15 12 56 61 9

Woman’s Education

Illiterate 13 13 52 63 16

1–4 Std 16 15 61 68 24

5–9 Std 15 12 61 72 24

10–11 Std 15 9 60 76 27

12 Std Some college 14 7 61 75 34

College graduate 15 6 61 75 30

Place of Residence

Metro cities 17 11 53 62 31

Other urban area 17 13 60 71 24

More developed village 14 15 60 72 21

Less developed village 11 8 52 64 18

Income

Lowest Quintile 12 12 56 66 19

2nd Quintile 14 13 57 68 18

3rd Quintile 16 12 57 69 20

4th Quintile 14 12 56 68 21

Highest Quintile 13 9 57 69 27

Social Groups

High Caste Hindu 10 8 50 66 23

OBC 12 11 57 68 21

Dalit 14 12 56 66 20

Adivasi 17 8 56 67 15

Muslim 24 24 64 70 23

Other religion 15 4 72 83 24

Note: Ever-married women age 15–49; NA—not calculated for women under 25 to avoid selectivity bias due

to early marriage; and + refers to 2 or more.

Source: IHDS 2004–5 data.

159

Table A.10.2b Women’s Social Support Networks by State

(per cent)

Per cent Per cent Natal Visit Natal Last

Marrying in Marrying Family Family Delivery

Same Cousins/ Lives 2+ times at Natal

Villiage/Town Relatives Near by a Year Home

All India 14 12 57 68 21

Jammu and Kashmir 23 21 55 88 31

Himachal Pradesh 11 0 61 77 7

Uttarakhand 8 1 57 51 1

Punjab 5 1 58 83 24

Haryana 3 2 39 84 13

Delhi 19 2 39 42 21

Uttar Pradesh 5 5 55 50 9

Bihar 6 6 24 50 16

Jharkhand 8 6 43 38 24

Rajasthan 11 2 53 71 18

Chhattisgarh 7 1 41 65 10

Madhya Pradesh 10 4 42 78 14

North-East 42 3 71 70 8

Assam 27 1 81 75 2

West Bengal 20 4 56 66 26

Orissa 17 9 65 52 11

Gujarat 8 3 75 85 33

Maharashtra, Goa 12 26 61 66 35

Andhra Pradesh 17 29 38 79 20

Karnataka 12 23 71 85 47

Kerala 28 3 84 90 23

Tamil Nadu 27 30 86 80 44

Note: Ever-married women aged 15–49 years; and + refers to 2 or more.

Source: IHDS 2004–5 data.

160

Table A.10.3a Average Expected Marriage Expenses and Dowry**

Average Wedding Per cent Usually Average

Expenses Giving Large Items Cash

Males Females in Dowry* Dowry

All India 59,879 92,853 24 22,421

Woman’s Age

15–19 41,941 63,143 15 15,534

20–4 52,065 80,698 21 19,181

25–9 58,818 90,936 25 22,823

30–9 59,903 93,620 24 22,880

40–9 67,344 1,03,741 25 24,138

Woman’s Education

Illiterate 46,045 66,766 19 15,298

1–4 Std 48,618 77,610 16 20,468

5–9 Std 64,054 1,02,405 26 24,896

10–11 Std 81,922 1,36,240 32 37,875

12 Std Some college 94,609 1,56,358 39 38,996

College graduate 1,27,966 2,05,526 43 44,488

Place of Residence

Metro cities 86,743 1,27,151 27 34,205

Other urban area 79,931 1,22,822 32 26,999

More developed village 56,680 93,492 23 24,055

Less developed village 45,734 67,942 19 15,902

Income

Lowest Quintile 43,426 64,553 16 17,175

2nd Quintile 41,680 63,782 16 14,959

3rd Quintile 51,105 78,422 20 19,240

4th Quintile 62,406 99,688 26 23,596

Highest Quintile 99,011 1,54,066 39 36,500

Social Groups

High Caste Hindu 89,394 1,35,470 36 34,345

OBC 58,466 90,468 23 22,989

Dalit 43,275 66,107 20 14,373

Adivasi 30,685 37,974 6 6,352

Muslim 55,913 91,744 22 21,634

Other religion 91,231 1,83,352 34 39,972

Notes: *Large items include TV, refrigerator, car, and motorcycles.

**Refers to practise in community and not women’s own experiences.

Source: IHDS 2004–5 data.

161

Table A.10.3b Average Expected Marriage Expenses and Dowry Across States**

Average Wedding Per cent Usually Average

Expenses Giving Large Items Cash

Males Females in Dowry* Dowry

All India 59,879 92,853 24 22,421

Jammu and Kashmir 1,53,027 2,10,342 38 18,233

Himachal Pradesh 94,237 1,14,839 72 6,555

Uttarakhand 61,216 80,619 52 9,441

Punjab 1,05,421 1,57,250 61 6,603

Haryana 1,12,527 1,58,056 65 3,709

Delhi 1,24,476 1,90,929 86 24,648

Uttar Pradesh 71,876 98,748 46 21,134

Bihar 50,801 77,798 19 28,971

Jharkhand 50,304 85,400 26 33,606

Rajasthan 88,607 1,14,649 35 8,328

Chhattisgarh 38,996 47,289 10 272

Madhya Pradesh 43,937 57,950 33 4,523

North-East 54,312 67,648 37 9,535

Assam 24,916 34,947 6 1,828

West Bengal 40,121 71,543 7 24,549

Orissa 53,619 88,745 29 25,496

Gujarat 77,586 92,331 7 2,743

Maharashtra, Goa 58,704 76,861 9 20,980

Andhra Pradesh 38,178 71,350 21 50,048

Karnataka 59,731 1,04,430 5 37,731

Kerala 49,709 1,93,112 10 72,954

Tamil Nadu 55,657 1,02,953 13 9,572

Notes: *Large items include TV, refrigerator, car, and motorcycles.

**Refers to practise in the community and not women’s own experiences.

Source: IHDS 2004–5 data.

162

Table A.10.4a Exepctation of Old Age Support from Sons and Daughters

Per cent Expecting to Per cent Expecting Financial

Live With… Help From...

Sons Daughters Daughters Sons Daughters Daughters

If Son If Son

Unable Unable

All India 85 9 24 86 11 30

Woman’s Age

15–19 70 9 21 70 10 27

20–4 78 9 23 79 11 30

25–9 85 11 26 85 12 32

30–9 87 10 24 87 11 30

40–9 89 8 23 89 11 29

Woman’s Education

Illiterate 89 7 22 90 9 27

1–4 Std 86 10 24 85 13 35

5–9 Std 83 10 24 84 12 32

10–11 Std 82 13 26 82 16 33

12 Std Some college 76 17 30 76 20 36

College graduate 71 18 31 70 19 33

Place of Residence

Metro cities 77 12 22 76 12 28

Other urban area 82 11 26 82 13 29

More developed village 87 10 25 87 13 33

Less developed village 88 7 22 88 9 29

Income

Lowest Quintile 86 10 25 85 12 32

2nd Quintile 86 9 24 87 10 30

3rd Quintile 86 8 21 87 11 29

4th Quintile 86 10 24 86 12 30

Highest Quintile 84 11 24 84 13 29

Social Groups

High Caste Hindu 84 9 22 84 12 28

OBC 87 9 24 87 11 30

Dalit 85 10 25 86 10 31

Adivasi 82 11 27 82 13 34

Muslim 87 8 22 87 10 30

Other religion 79 20 29 79 23 34

Source: IHDS 2004–5 data.

163

Table A.10.4b Statewise Expectation of Old Age Support from Sons and Daughters

Per cent Expecting to Per cent Expecting Financial

Live With… Help From...

Sons Daughters Daughters Sons Daughters Daughters

after Probing after Probing

All India 85 9 24 86 11 30

Jammu and Kashmir 96 6 26 93 10 34

Himachal Pradesh 78 10 31 80 9 25

Uttarakhand 77 6 29 78 6 31

Punjab 93 0 3 93 1 6

Haryana 95 3 8 95 3 12

Delhi 84 3 12 80 2 19

Uttar Pradesh 93 9 27 93 9 25

Bihar 98 3 15 98 4 16

Jharkhand 90 7 30 90 7 30

Rajasthan 95 1 17 95 1 19

Chhattisgarh 83 5 10 83 6 9

Madhya Pradesh 93 4 7 93 4 7

North-East 73 31 40 79 40 51

Assam 80 9 17 82 15 54

West Bengal 71 13 23 73 14 34

Orissa 88 7 26 88 12 35

Gujarat 83 9 31 83 14 28

Maharashtra, Goa 86 5 13 85 8 30

Andhra Pradesh 86 16 42 85 20 60

Karnataka 83 14 30 82 19 36

Kerala 75 36 45 75 43 56

Tamil Nadu 71 13 29 73 11 30

Source: IHDS 2004–5 data.

164

Table A.10.5a Women’s Control Over Resources and Physical Mobility

(in percentage)

Has Any Purchasing Large Items… Name on…* Per cent of Women Who…

Cash on Any Say Primary Bank Home Practice Need Cannot

Hand Decision Account Papers Purdah or Permission Go to

Ghunghat to Go to Health

A Health Center

Center Alone

All India 83 71 11 18 15 55 73 34

Woman’s Age

15–19 62 52 4 5 4 70 86 66

20–4 77 62 5 10 7 61 85 50

25–9 83 66 8 16 11 56 78 39

30–9 85 74 12 19 16 53 71 27

40–9 86 76 17 22 22 52 65 27

Woman’s Education

Illiterate 82 70 12 10 14 63 77 40

1–4 Std 80 70 11 13 15 53 72 31

5–9 Std 83 70 10 18 14 52 72 30

10–11 Std 84 72 9 32 16 42 68 26

12 Std Some college 89 76 9 39 18 36 66 23

College graduate 91 79 13 58 25 28 58 17

Place of Residence

Metro cities 92 84 12 33 18 36 56 16

Other urban area 88 73 13 25 17 44 67 23

More developed village 81 69 11 15 15 52 74 32

Less developed village 80 68 10 12 13 68 79 45

Income

Lowest Quintile 82 72 15 10 14 61 73 38

2nd Quintile 80 69 12 9 12 59 76 38

3rd Quintile 81 69 10 12 14 56 76 35

4th Quintile 83 72 11 19 14 52 73 31

Highest Quintile 88 71 9 37 20 48 68 27

Social Groups

High Caste Hindu 87 72 9 29 18 51 70 30

OBC 85 72 11 16 15 52 74 33

Dalit 82 72 14 13 14 55 74 33

Adivasi 78 62 10 10 13 47 76 38

Muslim 76 64 11 13 11 84 77 44

Other religion 77 80 11 33 16 15 63 15

Note: *Only for households with bank account or home ownership/rental papers.

Source: IHDS 2004–5 data.

165

Table A.10.5b Statewise Women’s Control Over Resources and Physical Mobility

(in percentage)

Has Any Purchasing Large Items… Name on…* Per cent of Women Who…

Cash on Any Say Primary Bank Home Practice Need Cannot

Hand Decision Account Papers Purdah or Permission Go to

Ghunghat to Go to Health

A Health Center

Center Alone

All India 83 71 11 18 15 55 73 34

Jammu and Kashmir 72 50 13 25 11 76 89 25

Himachal Pradesh 91 54 12 32 19 45 81 19

Uttarakhand 91 83 12 31 34 45 68 24

Punjab 89 84 8 24 6 32 82 21

Haryana 92 86 7 12 8 81 66 19

Delhi 96 94 9 40 25 43 58 11

Uttar Pradesh 86 78 9 18 14 87 77 50

Bihar 89 71 5 27 14 88 93 73

Jharkhand 88 52 15 26 9 59 68 52

Rajasthan 81 55 6 12 8 94 79 44

Chhattisgarh 79 50 6 7 3 58 90 62

Madhya Pradesh 74 68 7 7 16 93 91 47

North-East 76 75 38 26 20 28 67 13

Assam 69 47 18 6 6 68 64 48

West Bengal 60 74 15 16 8 70 72 31

Orissa 77 57 8 6 4 64 80 36

Gujarat 93 86 5 20 49 76 78 23

Maharashtra, Goa 88 66 8 23 11 38 56 14

Andhra Pradesh 96 66 10 14 13 12 83 26

Karnataka 83 80 12 15 29 12 89 23

Kerala 43 62 7 23 20 15 52 13

Tamil Nadu 94 86 31 11 13 10 42 12

Note: *Only for households with bank account or ownership/rental papers.

Source: IHDS 2004–5 data.

166

Table A.10.6a Common Perception of Domestic Violence in the Community

(in percentage)

In Respondent’s Community It is Common to Beat a Women if She…. No Wife

Beating

Goes Out Family Does Neglects Does Not Under Any

Without Not Give House Cook of These

Permission Expected Properly Conditions

Money

All India 39 29 35 29 50

Woman’s Age

15–19 48 33 40 35 43

20–4 42 31 35 29 46

25–9 41 30 35 29 48

30–9 38 29 35 30 50

40–9 35 26 32 28 53

Woman’s Education

Illiterate 45 33 38 33 43

1–4 Std 40 32 39 31 47

5–9 Std 36 27 32 27 53

10–11 Std 30 24 31 23 57

12 Std Some college 24 19 25 20 62

College graduate 18 15 20 15 70

Place of Residence

Metro cities 29 21 22 18 63

Other urban area 29 24 31 24 57

More developed village 41 31 39 32 46

Less developed village 44 31 36 32 46

Income

Lowest Quintile 47 35 41 36 41

2nd Quintile 42 32 38 32 46

3rd Quintile 40 30 35 30 48

4th Quintile 35 27 34 28 52

Highest Quintile 30 22 26 21 60

Social Groups

High Caste Hindu 33 25 29 23 57

OBC 40 31 37 31 48

Dalit 43 32 37 31 46

Adivasi 40 23 35 30 49

Muslim 42 30 36 31 47

Other religion 16 20 26 21 65

Source: IHDS 2004–5 data.

167

Table A.10.6b Statewise Common Perception of Domestic Violence in the Community

(in percentage)

In Respondent’s Community It is Common to Beat a Women if She…. No Wife

Beating

Goes Out Family Does Neglects Does Not Under Any

Without Not Give House Cook of These

Permission Expected Properly Conditions

Money

All India 39 29 35 29 50

Jammu and Kashmir 58 26 60 41 25

Himachal Pradesh 25 7 16 11 71

Uttarakhand 42 16 14 12 56

Punjab 12 9 7 7 86

Haryana 22 8 18 21 67

Delhi 16 21 12 7 70

Uttar Pradesh 40 25 23 19 50

Bihar 66 57 69 69 21

Jharkhand 58 55 54 46 22

Rajasthan 39 20 27 30 49

Chhattisgarh 22 9 13 15 73

Madhya Pradesh 48 23 37 29 48

North-East 10 10 23 8 73

Assam 8 10 11 8 84

West Bengal 30 28 28 24 65

Orissa 39 27 24 20 55

Gujarat 54 25 44 34 39

Maharashtra, Goa 61 41 56 44 25

Andhra Pradesh 20 29 23 17 63

Karnataka 56 50 52 46 39

Kerala 15 24 29 21 58

Tamil Nadu 20 16 37 28 56

Source: IHDS 2004–5 data.