Emerging

Patterns

of

Tampon

Use

in

the

Adolescent

Female:

The

Impact

of

Toxic

Shock

Syndrome

CHARLES

E.

IRWIN,

JR.,

MD,

and

SUSAN

G.

MILLSTEIN,

MS

Abstract:

From

November

1980

through

January

1981,

we

queried

714

post

menarchal

adolescents

(ages

12

to

19)

about

menstrual

product

use

at

menarche

(TI),

during

summer

1980

(T2),

at

last

menstrual

period

(T3),

and

about

intended

product

for

next

menstrual

period

(T4).

The

percentage

of

adolescents

reporting

use

of

tampons

at

each

point

in

time

were:

TI,

3.1

per

cent;

T2,

24.1

per

cent;

T3

(following

the

media

coverage

of

toxic

shock

syndrome

[TSS]),

19.3

per

cent;

and

T4,

19.5

per

cent.

Prior

to

TSS

coverage

there

was

a

shift

toward

tampon

use

in

141

of

the

672

Toxic

shock

syndrome

(TSS),

originally

reported

by

Todd,

et

al,'

in

seven

children

8-17

years

old,

has

emerged

as

a

disease

found

primarily

in

menstruating

women

between

the

ages

of

12-49.

The

Centers

for

Disease

Control

(CDC)

reports

that

99

per

cent

of

the

confirmed

cases

(n

=

928)

reported

since

1970

were

in

women

and

98

per

cent

of

these

women

had

the

onset

of

the

disease

during

a

menstrual

period.2

Since

1980,

several

reports3-8

have

discussed

the

epidemiologic

features,

recurrence,

risk

factors,

and

the

association

with

tampon

use

and

Staphylococcus

aureus.

From

these

studies

and

additional

work

at

the

CDC,9

there

has

emerged

an

association

between

TSS

and

the

presence

of

S.

aureus

in

the

vagina

and

the

use

of

tampons.

Evalua-

tion

of

the

prevalence

of

TSS

has

indicated

that

the

greatest

incidence

of

the

disease

is

among

White

adolescent

females

in

the

15-19

year

old

group.2

The

CDC

has

reported

only

seven

cases

in

Blacks,

three

in

Asians,

and

three

in

Hispan-

ics.

2

As

information

about

the

disease

was

made

available

by

the

CDC,

the

news

media

began

to

provide

extensive

coverage

on

TSS,

beginning

late

June

1980.

By

September

1980,

national

magazines,

newspapers,

and

television

and

radio

stations

were

reporting

on

the

disease

and

its

associa-

tion

with

menstruating

women

and

tampon

use.'0

On

Sep-

tember

22,

1980,

Proctor

and

Gamble

Company

removed

From

the

Adolescent

Medicine

Unit,

Department

of

Pediatrics,

University

of

California

School

of

Medicine,

San

Francisco.

Ad-

dress

reprint

requests

to

Charles

E.

Irwin,

Jr.,

MD,

Adolescent

Medicine

Unit,

Department

of

Pediatrics,

School

of

Medicine,

University

of

California,

San

Francisco

CA

94143.

This

paper,

submitted

to

the

Journal

September

8,

1981,

was

revised

and

accepted

for

publication

November

25,

1981.

subjects

who

used

napkins

(21

per

cent)

and

no

increase

in

napkin

use.

Following

media

coverage,

shifts

toward

tampon

use

among

napkin

users

de-

creased

to

2.3

per

cent

while

32.9

per

cent

of

the

168

summer

tampon

users

(T2)

shifted

to

the

use

of

napkins;

reasons

for

the

shift

were

significantly

associ-

ated

with

TSS

(p

<

.001).

Ethnicity

(White)

was

highly

associated

with

reported

tampon

use.

Following

TSS

coverage,

adolescents

in

all

ethnic

groups

decreased

their

tampon

use

at

the

same

rate.

(Am

J

Public

Health

1982;

72:464-467.)

Rely

brand

tampons

from

the

market

because

of

the

reported

apparent

association

with

TSS.2"1'

In

the

past,

media

coverage

of

specific

health

problems

has

been

shown

to

have

a

profound

impact

on

the

behavior

of

populations

at

risk.

Announcements

concerning

side

effects

of

oral

contraceptives

and

intrauterine

devices

have

had

a

significant

impact

on

the

behavior

of

women.

12

Media

coverage

on

TSS

has

been

reported

to

be

associated

with

a

21

per

cent

decrease

in

tampon

use

among

adult

women.2

Adolescents,

who

represent

the

age

group

at

highest

risk

for

developing

TSS,

have

not

been

specifically

studied.

Further-

more,

no

previous

study

in

the

scientific

literature

has

documented

tampon

use

in

females.

The

current

study

was

undertaken

to

examine

the

tampon-using

habits

of

adolescent

females

and

to

determine

if

adolescent

females

decreased

their

tampon

use

following

the

extensive

media

coverage

of

TSS.

Materials

and

Methods

Subjects

were

students

from

two

high

schools

in

San

Francisco

County

(n

=

629)

and

adolescent

patients

from

three

hospital-based

youth

clinics

(n

=

85).

Among

the

sample

of

714

subjects,

eight

were

missing

data

from

one

or

more

of

the

four

time

periods

(Tl

through

T4)

and

10

subjects

reported

using

methods

other

than

napkins

or

tampons.

These

18

subjects

(2.5

per

cent

of

the

original

sample)

were

excluded,

yielding

696

adolescents

who

did

not

differ

from

the

original

714

subjects

in

terms

of

age,

ethnic-

ity,

or

gynecologic

age.

The

academic

rankings

of

the

two

high

schools

were

one

and

seven,

respectively,

out

of

a

total

of

11

high

schools

in

the

county.

The

clinics

were

all

located

AJPH

May

1982,

Vol.

72,

No.

5

464

ADOLESCENT

TAMPON

USE/TOXIC

SHOCK

SYNDROME

50

(I)

cn

a)

a)

0

V

4-

U1)

C.)

40

-

Ti

=

FIRST

MENSTRUAL

PERIOD

30

_

20

_-

lO1_

I

I

TI

I

T,

T2

T3

T4

Time

point

FIGURE

1-Aggregate

Patterns

of

Tampon

Use

in

Adolescents

at

hospitals

in

Northern

California:

one

university,

one

private,

and

one

military.

A

two-part

questionnaire

was

constructed.

The

first

section

asked

about

patterns

and

choice

of

napkin

and

tampon

use;

respondents

who

changed

their

method

for

any

reason

were

asked

why

they

changed.

The

second

section

inquired

about

the

subject's

level

of

knowledge

of

the

disease,

sources

of

information

about

TSS,

and

demographic

data.

Information

was

elicited

about

napkin

or

tampon

use

at

four

time

periods:

with

first

menses

(Tl);

during

the

summer

of

1980

(T2);

with

last

menstrual

period

(T3);

intended

use

with

next

menstrual

period

(T4).

Salience

of

events,

memory

factors,

and

timing

of

media

reports

concerning

TSS

were

considered

in

the

questionnaire

design.

The

impact

of

men-

arche

serves

to

increase

the

reliability

of

the

T1

measure.'3

The

summer

(T2)

measure,

representing

the

period

prior

to

extensive

media

coverage

on

TSS,-may

have

already

begun

to

reflect

behavior

change

since

limited

media

reports

ap-

peared

as

early

as

June

1980.

However,

the

summer

is

a

long

and

well-defined

vacation

period,

and

given

the

problems

of

reliability

in

respondents'

reports

of

past

behavior,

selection

of

salient,

time-limited

periods

for

measurement

were

con-

sidered

crucial.

Use

during

the

last

menstrual

period

(T3)

is

considered

to

have

the

greatest

reliability

due

to

the

immedi-

acy

of

the

event.

In

the

high

school

samples,

the

questionnaire

was

administered

by

teachers

in

science

classes

to

all

students

who

wished

to

participate.

The

questionnaire

was

intro-

duced

as

a

health

survey,

and

teachers

did

not

mention

toxic

shock

syndrome.

In

clinic

sites,

the

questionnaire

was

given

to

patients

upon

their

arrival

to

the

clinic,

and

was

complet-

ed

prior

to

their

appointment.

Results

Subjects

The

sample

consisted

of

714

post-menarchal

adoles-

cents,

ages

12

to

19

years,

with

a

mean

age

of

15.5

years

(SD

=

1.13),

and

a

mean

gynecologic

age

of

3.27

years

(SD

=

1.48,

range

=

9-16

years).

Thirty-six

per

cent

of

the

subjects

were

Asian,

19.7

per

cent

White,

15

per

cent

Hispanic,

and

14.7

per

cent

Black.

The

remaining

14.4

per

cent

represented

other

racial

or

ethnic

groups.

The

largest

single

group

within

this

"other"

category

was

Filipino

(9.9

per

cent

of

total

sample).

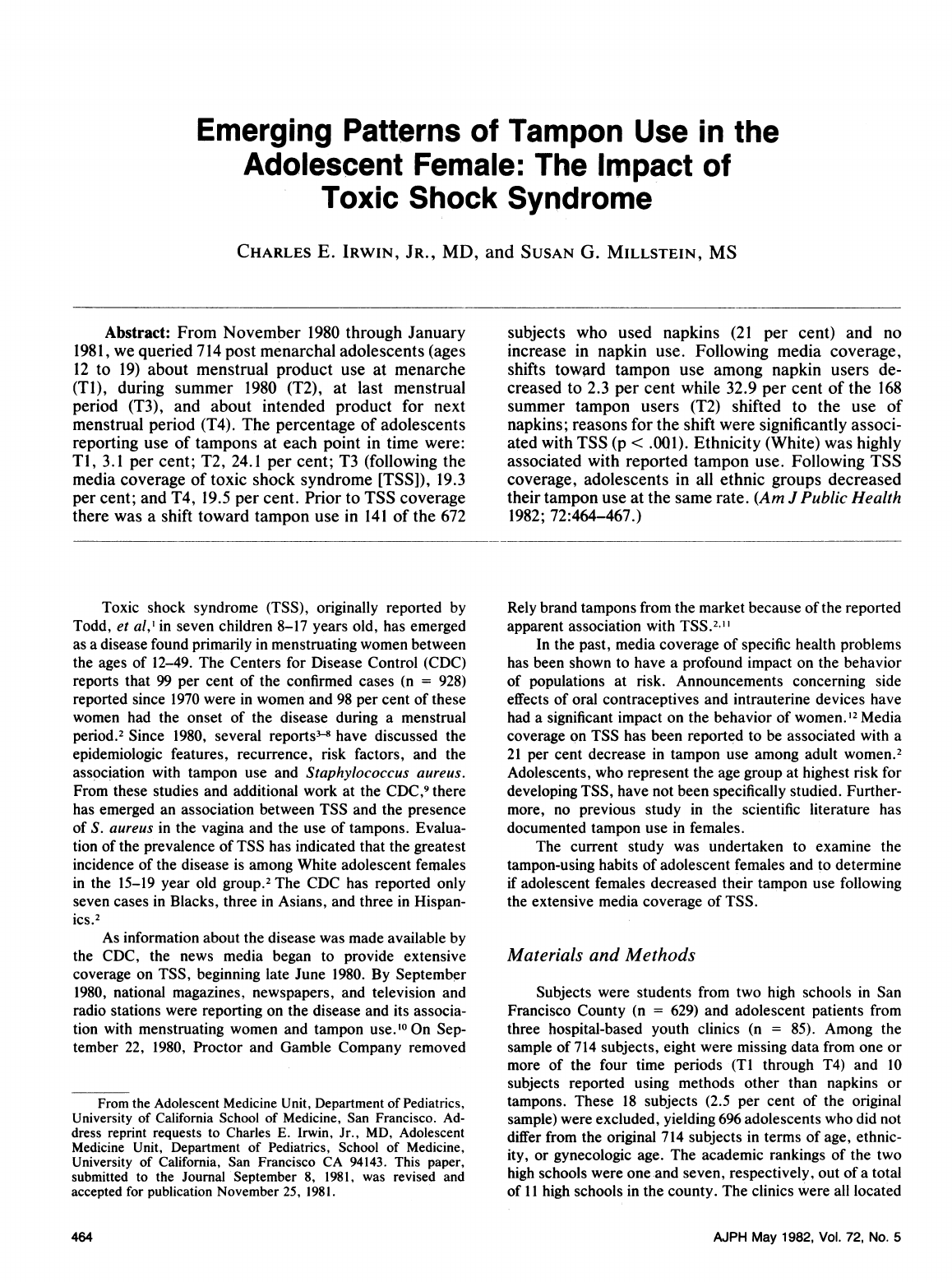

Aggregate

Patterns

of

Tampon

Usage

As

shown

in

Figure

1,

almost

all

of

the

subjects

(95.7

per

cent)

used

napkins

exclusively

during

their

first

menstrual

period.

During

the

summer

of

1980,

an

average

of

2.86

years

after

menarche,

the

percentage

of

tampon

users

had

risen

to

24.1

per

cent.

Following

mass

media

coverage

on

TSS,

the

percentage

of

adolescents

in

the

sample

using

tampons

during

all

or

part

of

their

menstrual

period

dropped

to

19.3

per

cent,

representing

a

20

per

cent

decrease.

For

their

next

menstrual

period,

19.5

per

cent

of

the

subjects

indicated

that

they

planned

to

use

tampons.

These

changes

over

the

four

time

periods

in

tampon

use

were

significant,

using

Cochran's

Q

statistic

(Q

=

247.7;

p

<

.001).

'

The

increase

in

tampon

use

during

the

3-4

year

post-menarchal

period

(TI

to

T2)

was

significant

(X2

=

140.0,

p

<

.001);

McNemar's

test),

as

was

the

decrease

in

tampon

use

following

coverage

on

TSS

(X2

=

19.58,

p

<

.001).

Differences

across

other

time

periods

were

not

significant.

The

proportion

of

tampon

users

before

and

after

the

most

extensive

publicity

on

TSS

was

examined

in

light

of

the

possibility

that

use

patterns

were

biased

by

the

inclusion

of

the

summer

(T2)

measure.

Increased

activity

levels

during

the

summer

may

be

associated

with

increased

tampon

use,

irrespective

of

TSS

coverage.

Even

excluding

all

subjects

who

used

tampons

during

the

summer

for

reasons

relating

to

activity

(n

=

20)

did

not

significantly

alter

aggregate

use

patterns;

tampon

use

dropped

from

21.8

per

cent

during

the

summer

to

17.8

per

cent

at

T3,

which

remained

a

significant

decrease

(X2

=

13.26,

p

<

.001).

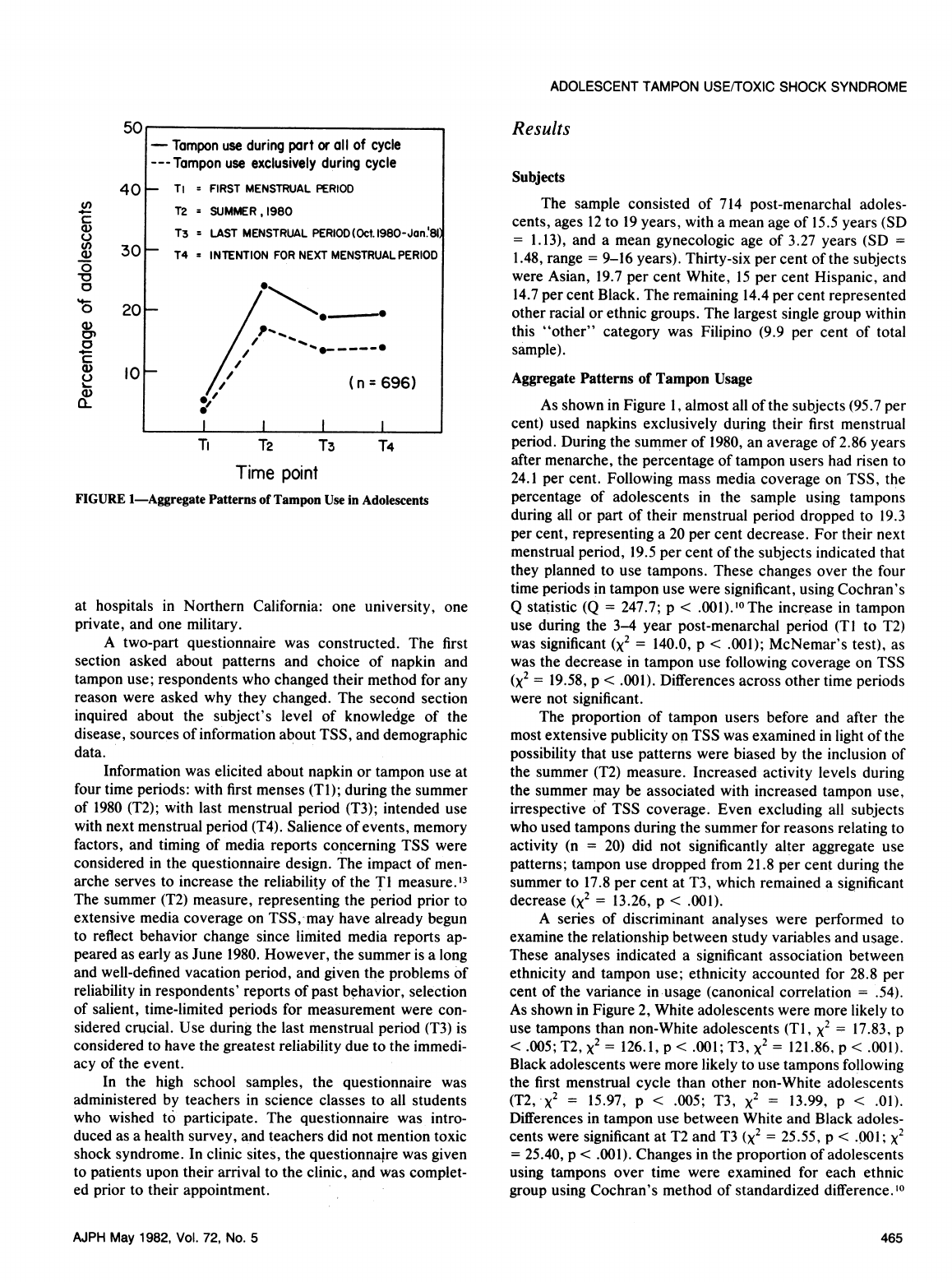

A

series

of

discriminant

analyses

were

performed

to

examine

the

relationship

between

study

variables

and

usage.

These

analyses

indicated

a

significant

association

between

ethnicity

and

tampon

use;

ethnicity

accounted

for

28.8

per

cent

of

the

variance

in

usage

(canonical

correlation

=

.54).

As

shown

in

Figure

2,

White

adolescents

were

more

likely

to

use

tampons

than

non-White

adolescents

(TI,

=

17.83,

p

<

.005;

T2,

X2

=

126.1,

p

<

.001;

T3,

X2

=

121.86,

p

<

.001).

Black

adolescents

were

more

likely

to

use

tampons

following

the

first

menstrual

cycle

than

other

non-White

adolescents

(T2,

X2

=

15.97,

p

<

.005;

T3,

x2

=

13.99,

p

<

.01).

Differences

in

tampon

use

between

White

and

Black

adoles-

cents

were

significant

at

T2

and

T3

(X2

=

25.55,

p

<

.001;

X2

=

25.40,

p

<

.001).

Changes

in

the

proportion

of

adolescents

using

tampons

over

time

were

examined

for

each

ethnic

group

using

Cochran's

method

of

standardized

difference.'0

AJPH

May

1982,

Vol.

72,

No.

5

-Tampon

use

during

part

or

all

of

cycle

---Tampon

use

exclusively

during

cycle

T2

=

SUMMER,

1980

T3

a

LAST

MENSTRUAL

PERIOD(Oct.1980-Jon.81)

T4

x

INTENTION

FOR

NEXT

MENSTRUAL

PERIOD

0/

(

n

=

696)

//

~~~(n

=696)

465

IRWIN

AND

MILLSTEIN

0I

40-

a)5

4

30

-

A

Blac

01

20

-

Other

10

Ti

T2

T3

T4

Time

point

FIGURE

2-Differences

in

Tampon

Use

by

Race

Comparison

of

the

increase

in

tampon

use

from

Tl

to

T2

yielded

significant

differences

between

ethnic

groups

(X2

=

149.29,

p

<

.001).

The

decrease

in

tampon

use

from

T2

to

T3

was

invariant

across

ethnic

groups.

Individual

Patterns

of

Tampon

Use

Although

aggregate

patterns

of

tampon

use

allow

one

to

examine

overall

behavior

change

within

a

sample,

they

do

not

provide

information

concerning

use

for

individuals.

Knowledge

about

an

individual's

use

across

all

four

points

in

time

allows

one

to

identify

shifts

toward

the

use

of

specific

methods.

A

shift

toward

a

specific

method

was

defined

in

this

study

as

any

increase

in

the

use

of

that

method

by

an

individual.

Thus,

subjects

who

used

napkins

exclusively

for

their

first

menstrual

cycle,

but

used

both

napkins

and

tampons

during

the

summer,

were

considered

to

be

shifting

toward

the

use

of

tampons

at

T2.

Similarly,

individuals

who

used

tampons

during

the

summer

but

changed

to

both

tampons

and

napkins

for

their

last

menstrual

period

were

considered

to

have

demonstrated'

a

shift

toward

napkin

use

at

T3.

Prior

to

TSS

reporting

there

was

a

shift

toward

tampon

use

in

21

per

cent

of

the

672

subjects

who

had

ever

used

napkins.

There

was

no

increase

in

napkin

use

during

that

time.

Following

the

major

impact

of

TSS

coverage,

shifts

toward

tampon

use

among

napkin

users

decreased

to

2.3

per

cent,

while

32.9

percent

of

the

168

tampon

users

moved

to

the

use

of

napkins.

Overall,

90

per

cent

of

the

sample

did

not

change

methods

from

T2

to

T3;

82

per

cent

of

these

were

subjects

who

continued

to

use

napkins.

Among

adolescents

who

did

change

their

methods

following

TSS

publicity

(n

=

69),

81

per

cent

did

so

in

the

direction

of

increased

napkin

use.

TSS

and

Adolescents'

Reasons

for

Method

Use

Among

the

6%

subjects,

92

per

cent

offered

reasons

for

their

choice

of

method.

Twenty-seven

per

cent

claimed

that

TSS

was

a

factor

influencing

their

choice

of

method.

Ten

per

cent

of

tampon

users

mentioned

TSS;

most

of

these

subjects

believed

that

their

brand

of

tampon,

or

the

way

in

which

they

used

tampons,

protected

them

from

TSS.

To

test

whether

subjects'

reasons

for

using

a

particular

method

were

associ-

ated

with

their

patterns

of

use,

a

linear

logistic

regression

analysis

was

performed.

"

Subjects

who

used

napkins,

whether

or

not

they

had

ever

used

tampons,

were

more

likely

to

attribute

their

choice

of

method

to

TSS

and

safety

than

were

tampon

users

(p

<

.001).

Subjects

who

had

never

used

tampons

were

less

likely

to

mention

TSS

or

safety

as

a

factor

influencing

their

choice

than

were

subjects

who

shifted

from'tampon

to

napkin

use

(p

<

.001).

Discussion

A

significant

decrease

in

the

use

of

tampons

was

associ-

ated

with

the

extensive

publicity

regarding

TSS

in

this

sample

of

adolescents.

Eighty-one

per

cent

of

the

subjects

who

reported

a

change

in

behavior

decreased

their

use

of

tampons.

This

decrease

in

tampon

use

remained

significant

when

controlling

for

increases

in

activity

during

the

summer.

There

are

no

data

available

to

suggest

seasonal

variation.

Because

TSS

information

began

to

appear

in

the

media

during

June

1980,

it

is

possible

that

tampon

use

during

the

summer

(T2)

may

have

already

reflected

some

of

the

impact

of

that

coverage.

If

so,

the

reported

20

per

cent

decrease

in

tampon

use

following

media

coverage

represents

a

conserva-

tive

estimate.

Examination

of

the

reasons

adolescents

gave

for

using

a

particular

method

suggests

that

the

impact

of

TSS

publicity

was

not

limited

to

-adolescents

who

decreased

their

tampon

use.

While

10

per

cent

of

the

sample

demonstrated

a

change

in

behavior,

27

per

cent

attributed

their

choice

of

a

particular

method

to

TSS,

health,

or

safety.

Over

one-fourth

of

the

young

women

who

never

used

tampons

mentioned

TSS

or

the

safety

of

tampons

as

a

factor

influencing

their

decision

to

continue

using

napkins.

Some

of

these

adolescents

may

have

eventually

used

tampons

if

TSS

had

not

been

well

publicized

at

such

an

early

point

in

their

menstrual

history.

Ethnicity'was

the

strongest

correlate

of

tampon

use

at

any

point

in

time.

White

adolescents

were

significantly

more

likely

to

be

tampon

users

than

non-Whites.

Following

the

first

menstrual

period,

tampon

use

was

more

likely

to

occur

in

both

White

and

Black

adolescents

irrespective

of

TSS

coverage.

If

our

sample

is

representative

of

ethnic

patterns

of

tampon

use,

our

data

may

begin

to

answer

the

question

concerning

the

ethnic

distribution

of

TSS.

The

CDC

has

reported

only

seven

cases

in

Blacks,

three

in

Asians,

and

three

in

Hispanics.2

Our

data

indicate

that

Asian

and

His-

panic

adolescents

generally

do

not

use

tampons.

As

such,

they

have

essentially

removed

themselves

from

the

suscepti-

ble

population.

Black

adolescents,

who

account

for

fewer

cases

of

TSS

than

White

adolescents,

also

show

significantly

AJPH

May

1982,

Vol.

72,

No.

5

466

ADOLESCENT

TAMPON

USE/TOXIC

SHOCK

SYNDROME

lower

rates

of

tampon

use

than

Whites

(p

<

.001).

Our

methodology

and

sites

did

not

allow

us

to

inquire

about

socioeconomic

status.

From

our

knowledge

of

the

sites,

socioeconomic

status

does

not

appear

to

be

a

factor

in

patterns

of

use.

Despite

the

fact

that

tampon

use

in

general

was

signifi-

cantly

associated

with

ethnicity,

it

is

of

interest

that

the

decrease

in

tampon

use

following

TSS

coverage

was

not

associated

with

ethnicity.

Adolescents

in

all

ethnic

groups

demonstrated

similar

decreases

in

tampon

use.

This

suggests

that

factors

which

influence

a

young

woman

to

use

tampons

are

not

the

same

factors

which

are

responsible

for

the

decrease

in

tampon

use

following

TSS

publicity.

A

comparison

of

aggregate

patterns

of

tampon

use

in

our

adolescent

sample

with

reported

patterns

of

use

in

adult

women

suggests

that

adolescents'

risk

of

contracting

TSS

may

be

even

higher

than

the

risk-ratio

reported

in

epidemio-

logical

studies.

Adolescents

are

less

likely

than

older

women

to

use

tampons;

only

23

per

cent

of

our

adolescent

sample

used

tampons

exclusively

at

T2,

compared

with

tampon

usage

in

70

per

cent

of

adult

women.5

Adolescents

thus

represent

a

smaller

proportion

of

the

population

of

tampon

users.

Despite

this,

the

prevalence

of

TSS

remains

highest

within

the

adolescent

group.

The

proportion

of

adolescents

in

this

sample

who

used

tampons

prior

to

TSS

coverage

is

lower

than

estimates

supplied

by

tampon

industry

sources

or

independent

con-

sumer

surveys,

which

report

tampon

use

by

44-70

per

cent

of

American

women.'6

This

discrepancy

may

be

due

to

cohort

age

or

ethnic

differences

or

other

characteristics

of

our

sample.

Since

September

1980,

there

has

been

a

marked

de-

crease

in

the

number

of

reported

cases

of

TSS.

The

CDC

has

postulated

several

reasons

for

a

decrease

in

the

reported

disease

including:

lag

time

from

the

onset

to

the

confirmation

of

the

disease;

strict

criteria

for

the

diagnosis

of

the

disease;

a

diminished

interest

in

reporting

the

disease;

awareness

of

women

about

TSS

and

seeking

of

medical

attention

earlier

in

the

progress

of

the

disease;

a

change

in

tampon

wearing

habits;

and,

removal

of

Rely

tampons

from

the

market.2

According

to

the

CDC,

the

tampon

industry

states

that,

in

July

1980,

70

per

cent

of

the

women

in

the

United

States

used

tampons,

but

only

55

per

cent

did

so

in

November/

December

1980.

This

represents

a

21

per

cent

decrease.

Our

study

confirms

a

parallel

change

in

adolescent

behavior

with

a

20

per

cent

decrease

in

the

use

of

tampons.

This

decrease

in

tampon

use

may

help

explain

the

significant

decrease

in

the

reported

incidence

of

the

disease.

TSS

appears

to

have

had

a

profound

impact

on

the

patterns

of

tampon

users

in

adolescent

females.

Future

studies

investigating

tampon

use

will

need

to

consider

ethnic

characteristics

since

the

use

of

tampons

appears

to

be

strongly

associated

with

ethnicity.

In

addition,

socioeco-

nomic

status

should

be

monitored

to

assess

the

differences

between

socioeconomic

class

and

culture.

REFERENCES

1.

Todd

J,

Fishaut

M,

Kapral

F,

Welch

T:

Toxic

shock

syndrome

associated

with

phage-group-l

staphylococci.

Lancet

1978;

2:1116-1118.

2.

Toxic

shock

syndrome-United

States.

MMWR

1981;

30:25-33.

3.

Davis

JP,

Chesney

PH,

Wand

PH,

et

al:

Toxic

shock

syndrome:

epidemiologic

features,

recurrence,

risk

factors,

and

preven-

tion.

N

Engi

J

Med

1980;

303:1429-1435.

4.

Shands

KN,

Schmid

GP,

Dan

B,

et

al:

Toxic

shock

syndrome

in

menstruating

women:

association

with

tampon

use

and

Staphy-

lococcus

aureus

and

clinical

features

in

52

cases.

N

Engi

J

Med

1980;

303:1436-1442.

5.

Glasgow

LA:

Staphylococcal

infection

in

the

toxic

shock

syn-

drome.

N

Engl

J

Med

1980;

303:

1473-1475.

6.

Tofte

RW,

Williams

DN:

Toxic

shock

syndrome:

clinical

labo-

ratory

features

in

15

patients.

Ann

Intern

Med

1981;

94:149-156.

7.

Fisher

RF,

Goodpasture

HC,

Peterie

JD,

et

al:

Toxic

shock

syndrome

in

menstruating

women.

Ann

Intern

Med

1981;

94:156-163.

8.

Shands

KN,

Dan

B,

Schmid

GP:

Toxic

shock

syndrome:

the

emerging

picture.

Ann

Intern

Med

1981;

94:264-266.

9.

Follow-up

on

toxic

shock

syndrome.

MMWR

1980;

29:441-445.

10.

Todd

J:

Toxic

shock

syndrome-scientific

uncertainty

and

the

public

media.

Pediatrics

1981;

67:921-923.

11.

Toxic

shock

syndrome-Utah.

MMWR

1980;

29:495-496.

12.

Jones

EF,

Beniger

JR,

Westoff

CR:

Pill

and

IUD

discontinua-

tion

in

the

United

States,

1970-1975:

the

influence

of

the

media.

Fam

Plan

Perspect

1980;

12:293-300.

13.

Marquis

KH,

Cannell

CF:

Effect

of

some

experimental

inter-

viewing

techniques

on

reporting.

Health

Interview

Survey,

NatI

Ctr

Hlth

Stat,

Vital

and

Health

Statistics,

1977;

Series

2,

No.

2:1.

14.

Fleiss

JL:

Statistical

Methods

for

Rates

and

Proportions.

New

York:

John

Wiley,

1973.

15.

Halperin

M,

Blackwelder

WC,

Verrier

JI:

Estimation

of

the

multivariate

logistic

risk

function:

a

comparison

of

the

discrimi-

nant

function

and

maximum

likelihood

approaches.

J

Chron

Dis

1971;

24:125-158.

16.

Menstrual

tampons

and

pads

survey.

Consumer

Rep

1978;

March:

127-131.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We

are

indebted

to

the

students

and

teachers

of

two

San

Francisco

high

schools,

and

the

patients

of

Mt.

Zion

Hospital,

the

University

of

California,

San

Francisco,

and

Travis

Air

Force

Base

for

participating

in

this

study;

to

Janet

LaFlamme

for

assistance

with

the

manuscript;

to

Abe

Bernstein

for

editorial

assistance;

and

Nancie

Kester

and

Bruce

Stegner

for

data

entry.

This

research

was

supported

in

part

by

MCT00978

from

the

Office

of

Maternal

and

Child

Health,

Bureau

of

Community

Health

Services,

US

Department

of

Health

and

Human

Services.

AJPH

May

1982,

Vol.

72,

No.

5

467