CHAPTER FIVE

CHANGES IN FERTILITY AND

MARRIAGE RATES IN TAIWAN

Ching-li Yang and Hung-Jeng Tsai

Abstract

The fertility rate of Taiwan has been decreasing since World War II. The total

fertility rate (TFR) of 7.04 in 1953 has fallen below replacement level since then

(net reproduction rate was 0.96 in 1984). The number went up and down within

a range of about 1.75 from 1986 to 1996. When TFR dropped below 1.5 in 1998,

people considered this low fertility rate a temporal phenomenon, as it was both

a “tiger year” and a “year of loneliness.” Although the number climbed back

only a little (to 1.55), it was still not taken as change of childbearing patterns

because it was thought that people might delay to have children until the year

2000, a “dragon year.” In 2000, however, the TFR returned only to 1.68, which

was not strong enough to compensate for the loss of the previous two years.

The situation has been even worse since 2000. By 2005, TFR had reached 1.12.

These data demonstrate that the TFR has been in another wave of

decrease since 1997, with the millennium showing an exceptional effect

ofa“dragonyear.”Inthischapter,werstlayoutthetrendsofthefertility

ratesofbothchildbearingandmarriedwomen toexplaintheinuenceof

marriage rates on fertility. We then turn to the changes of marriage rates

62

Women in Taiwan: Socialcultural Perspectives

and discuss the impacts of women’s elevated socioeconomic status and

persistent conventional assortive mating. Finally, we present the possible

directions of social policy in dealing with these changes of marriage pattern

in the perspective of lifestyle preference proposed by Hakim in Work-Lifestyle

Choices in the 21st Century: Preference Theory.

Introduction

The fertility rate in Taiwan has been decreasing since World War II (WWII). The total

fertility rate (TFR) was 7.04 in 1953 but has declined to below replacement level in the 30

years since (net reproduction rate was 0.96 in 1984). The gure was a range of about 1.75

from 1986 to 1996. When TFR dropped from 1.77 in 1997 to 1.46 in 1998, people considered

this low fertility rate to be a temporary phenomenon, as it was both a “tiger year” and a “year

of loneliness.”

68

Although TFR climbed back only a little bit (1.56 in 1999), it was still not

taken as change of childbearing patterns because people might delay having children until

the year 2000, a “dragon year.”

69

In 2000, however, the TFR returned only to 1.68, which

is not strong enough to compensate for the loss of the previous two years. The situation has

become even worse since then. In 2005, TFR declined to 1.12, as shown in Figure 1. These

data demonstrate that the TFR has already commenced another period of decrease since

1997, while the millennium spike was actually an exceptional effect of a dragon year.

Although marriage is not a requirement of childbearing, it is an important condition

in Taiwan. Because fertility rate is equal to the rate of currently married women times the

fertility rate of married women, the fertility decrease could be caused by either a change

in the fertility rate of the married population or a change in the marriage and divorce

rates if the reproductive behavior of the married population has not changed. Before the

1990s, most Taiwanese got married at younger ages. Because of economic pressure or the

needs of family care, remarriage rates were high after divorce or loss of a spouse (Lee,

1994). After 2000 or so, half of the demographic group suitable for child bearing (25–34

years old) was still single. As the divorce rate gradually rises and the remarriage rate for

divorced people goes down, the fertility rate is no longer easy to maintain.

A marriage is not only about the willingness, but also the existence, of “adequate”

partners. The conventional forms of assortive mating in Taiwan are homogamy and

women’s hypergamy (Tsai, 1994; Tsay, 1996). As the gender differences in education

and income are narrowing, eventually, some men of lower social and economic status

and women of higher status will not meet their “adequate” partners. In the case of a

63

5. Changes in Fertility and Marriage Rates in Taiwan

closed population, which means immigration and migration are very limited, marriage

pressure will contribute to transform the pattern of women’s hypergamy when the social

and economic gap shrinks between genders. Taiwan is no longer a closed population,

however, and the status promotion empowers women’s resistance to the pressure of

getting married. Both of these factors result in the increasing need for foreign brides for

men and the growing visibility of women who have never been married.

In this chapter, we rst lay out the tendency of both the fertility rates and the

marriage rates of women to explain the inuence of marriage rates on fertility. We

then turn to the changes in marriage rates and discuss the impacts of women's elevated

socioeconomic status and persistent conventional assortive mating. Finally, we put on

the table the possible directions of social policy in dealing with these changes in marriage

patterns from the perspective of lifestyle preference proposed by Hakim (2000).

Marriage Rate Effects on Fertility

The fertility rates of married women and women aged 15 to 49 years were almost

identical before the mid-1980s but diverged after 1986. In this section, we compare the

Figure 1. Total Fertility Rates in Taiwan, 1951–2005. Source: Department

of Household Registration Affairs, Ministry of Interior, Taiwan-Fukien

Demographic Fact Book,various years.

64

Women in Taiwan: Socialcultural Perspectives

trends in age-specic fertility of married women to that of childbearing women, to explain

the inuence of the proportion of currently married women on fertility.

Age-Specic Fertility Rates

The age distribution of fertility is basically a normal curve moderately skewed to the

right. Lower age groups tend to have a lower marriage rate and thus lower fertility rate due

to education and employment. The middle age group has the highest marriage and fertility

rates because of improved psychological, physical, and social conditions. Although most

people in the older age group are married, they still reach a lower age-specic fertility rate

because of the limitations caused by biological change. Figure 2 shows the ve-year age-

specic fertility rate of childbearing women from 1951 through 2005. Although 1967 is the

year with the largest downturn, 1986 is the lowest point of the rst descending wave, and

1997, the starting point of the second descending wave.

Figure 2. Age-Specic Fertility Rates, 1965–2005. Source: Department

of Household Registration Affairs, Ministry of Interior, Taiwan-Fukien

Demographic Fact Book, various years.

65

5. Changes in Fertility and Marriage Rates in Taiwan

According to Figure 2, the fertility rates of the lower age groups did not decline

much from 1951 to 1967. Declines in age-specic fertility rates were centered on older age

groups (above 30 years old); thus, the age distribution of fertility rates has a positive skew.

From 1965 to 1986, the fertility rates of all age groups generally dropped with a similar

distribution curve. The period of 1986 to 1997, however, saw another pattern emerge:

The TFR did not change signicantly, but the timing of fertility was postponed. That is,

declines in age-specic fertility rates shifted to younger age groups, and the rates of the

higher age group increased slightly. Finally, from 1997 to 2005, postponement of fertility

continued and fertility rates dropped down further throughout all age groups. Both of

these patterns contribute to the comprehensive downturn of fertility that makes recovery

of fertility appear even more hopeless.

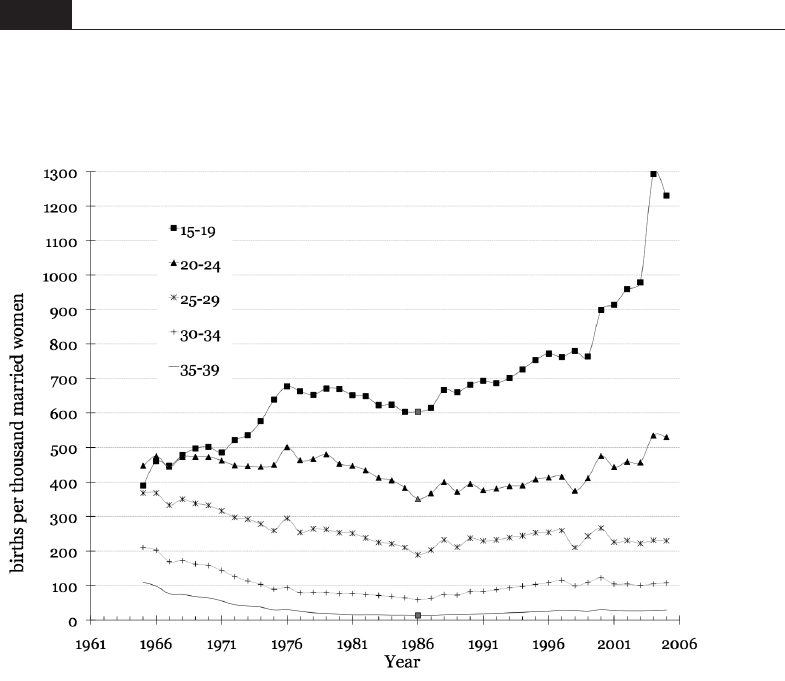

Age-Specic Marital Fertility Rates

In the past, births out of wedlock were scarce for most societies, and discussions on

women’s childbearing behavior usually focused on married women. As 15–19 years old

is not considered an adequate age for marriage in Taiwan, those who chose to marry at

younger ages always married because of pregnancies, which resulted in a drastic increase

in marital fertility. The age distribution of marital fertility is therefore not a normal curve

but a rectangular hyperbola. Setting time rather than age on the x-axis, Figure 3 illustrates

the historical changes in age-specic marital fertility rates (AMFR) by 5-year age groups

from 1965

70

to 2005. Although married women’s fertility rates all declined with the same

trend of general childbearing fertility between 1965 and 1986, their trends differed from

1987 to 1997. Figure 3 shows the reverse of the declining trend for marital fertility rates

for all age groups

71

after 1987. As we have mentioned, there was a shift due to postponing

fertility, with a at TFR for all women during this period; that is, fertility rates declined for

lower age groups and increased for older age groups. This means the increase in marital

fertility was balanced by a decline in the marriage rate, resulting in a at, under-replaced

TFR. The TFR resumed its decline after 1998 (with an exception in 2000), due to a slow

down of the increase in the marital fertility component and a continued speeding-up of

the decrease in the marriage-rate component. All these gures indicate that, recently,

fewer births were resulting from fewer marriages.

Changes in Marriage Rates

Declining marriages resulted in more bachelorhood, divorce, and widowhood.

Because the constraint of childbearing age makes widowhood produce little inuence

66

Women in Taiwan: Socialcultural Perspectives

on fertility, we focus on the changes in marriage and divorce. Taiwan was a society that

was nearly 100% “married for life” during the 1980s. Most men had already experienced

marriage by the age of 35 years, and women before 30. The age of rst marriage has been

postponed to a signicant extent since the 1990s, and the percentage of people who are

single continues to rise in the 21

st

century. The proportion of never-married men aged 30

to 34 years rose from 13.4% in 1980 to 43.30% in 2005, as seen in Table 1. The same

proportion for men aged 34-39 years rises from 7.06% to 22.21%. Similar trends apply to

women. The proportion of single women in the age group from 25 to 29 years climbed from

19.64% in 1980 to 61.23% in 20005; for the group aged 30 to 34 year, it rose from 7.74%

to 28.67%; and for the group aged 35 to 39 years ascended 12%, from 3.88% to 15.92%.

In addition to continuous marriage postponement and fewer marriages, the divorce

rate also rose quite signicantly from 1980 to 2005. In 1980, divorce rates in all age

groups for both men and women were below 2%. The proportion of divorced persons 30

to 34 years old generally kept steady and did not rise as time went by, implying that the

Figure 3. Age-Specic Marital Fertility Rates, 1965–2005. Source:

Department of Household Registration Affairs, Ministry of Interior, Taiwan-

Fukien Demographic Fact Book, various years.

67

5. Changes in Fertility and Marriage Rates in Taiwan

growth in divorce numbers had stopped. However, the situation changed between 1980

and 2005, as divorce rates kept rising for all age groups.

Table 1. Distribution of Population by Sex, Age, and Marital Status, 1980 and 2005

Age 15–19 20–24 25–29 30–34 35–39 40–44 45–49 50+

1980 Male

Single 99.07 86.95 40.27 13.48 7.06 5.75 7.23 13.82

Married 0.93 12.90 58.92 84.87 90.79 91.49 88.74 76.06

Divorced 0.00 0.13 0.71 1.39 1.62 1.69 1.95 1.97

Widowed 0.00 0.02 0.10 0.26 0.52 1.07 2.08 8.15

2005

Single 99.88 96.93 78.19 43.30 22.21 13.48 8.90 5.02

Married 0.11 2.69 19.46 50.95 69.28 76.56 80.25 81.63

Divorced 0.01 0.38 2.33 5.67 8.30 9.55 10.07 6.14

Widowed 0.00 0.00 0.02 0.08 0.21 0.41 0.79 7.21

1980 Female

Single 94.96 59.44 19.64 7.74 3.88 2.92 2.57 3.05

Married 4.99 39.94 78.61 89.57 92.52 92.13 89.96 66.54

Divorced 0.04 0.49 1.30 1.67 1.60 1.48 1.48 1.35

Widowed 0.01 0.13 0.45 1.03 2.00 3.47 5.99 29.05

2005

Single 99.29 90.48 61.23 28.67 15.92 10.25 7.10 3.74

Married 0.65 8.30 34.45 63.42 73.34 76.28 76.89 64.60

Divorced 0.06 1.18 4.12 7.36 9.51 10.89 11.14 5.28

Widowed 0.00 0.04 0.19 0.55 1.24 2.58 4.87 26.38

Note: Figures in percentage.

Source: 2005 Taiwan-Fukien Demographic Fact Book, Department of Household

Registration Affairs, Ministry of Interior.

Generally, this change in marriage rates is considered largely a result of the improved

socioeconomic status of women. From the point of view of rational choice, economists

explain an individual’s decision to marry by his/her calculation of cost and utility. One

renowned theory is the specialization and trading model of marriage posed by Gary Becker

(1991). Becker argues that traditionally, men’s specialty has been to make money from the

labor market, while women’s specialty has been household labor and children rearing, so

forming a family can thus satisfy both men’s and women’s needs by a division of labor.

As women enter the labor market and their wage level gradually catches up with that of

68

Women in Taiwan: Socialcultural Perspectives

men, however, the “prot” of marriage, incentive for marriage, and cost for divorce will

all decrease. According to this theory, nonmarital and divorce rates will continue to go up

along with the expansion of economic development and education.

Although Becker’s theory does explain declining marriages to a certain extent,

empirical data at an individual level show that the correlation of women’s economic

capability, marriage formation, and marriage stability are either irrelevant or positive

(Clarkberg, 1999; Goldscheider & Waite, 1986; Oppenheimer & Lew, 1995). Moftt (2000)

revises Becker’s theory and proposes a new argument involving what he calls the price

effect and the income effect. Moftt calls the relation between marriage rates and the

income gap between men and women the price effect, which implies that a narrower

income gap will result in a lower marriage rate as the price effect goes up. Income effect is

the relation between the total income of men and women and the marriage rate, meaning

that marriage rates will rise as total income increases. As a consequence, on the one hand,

the US marriage rates slide down as the wage difference between the genders narrows,

while the marriage rate for less-educated women records a higher downturn ratio than

that of more-educated women. Moftt’s conclusion implies a specic pattern of assortive

mating in the US. The potential partners for less-educated men are less-educated women.

As men in these situations cannot depend on their wives’ wages to promote family income,

their income effect is not signicant and the marriage rate goes down with the falling male

wage. On the other hand, highly educated women usually marry highly educated men, and

as they gain economic ability, the greater price effect for the women results in a falling

marriage rate.

Interestingly, the marriage rate of well-educated Japanese women shows a greater

decline than that of less-educated women. Ono (2003) thus extends the argument over

the dimension of culture and explains the relation between women’s wage and marriage

rate in terms of social-role differentiation by gender. Japan, the US, and Sweden represent

societies with degrees of role differentiation by gender from high to median and low.

In the US and Sweden, the rates of rst marriage rise with higher women’s wages. The

relation shows the opposite direction in Japan. Ono’s explanation is that women’s labor

participation has to face a stronger conict with family obligation in a society with the

expectation of men being responsible for work outside of the family and women for work

inside. For Japanese women, their economic return might not be higher than for their

counterparts in the US and Sweden, but their loss will be larger once they get married

because they have a greater family obligation to comply with. Fertility rates also drop

in this case, as a society like Japan cannot accept nonmarital births. In other words, if

69

5. Changes in Fertility and Marriage Rates in Taiwan

economic development demands women’s labor participation while the whole society

does not respond to this change institutionally and culturally, it would be possible to bring

falling marriage and fertility rates into existence.

In the next section, we will rst use the changes of labor-participation rate, the

gender difference of enrolled college students, and the wage difference of unmarried

employees to describe the rise of women’s socioeconomic status. Second, we will suggest

that conventional forms of assortive mating, homogamy, and women’s hypergamy are

not diminished by the rise of women’s socioeconomic status but rather produce falling

marriage rates. Finally, we provide marital status life tables to discuss the possible future

development of marriage rates and their implications for fertility.

Changes of Women’s Socioeconomic Status: Female Labor Participation

The growth of female labor participation has to do with economic change, increase

of human capital, and changing gender roles. During WWII, women went to work

as compensation for male labor loss due to war. This opened the door for women’s

employment. As the third industrial sector developed, job opportunities for women rose

because demands for female labor steadily increased (Pampel & Tanaka, 1986).

Taiwan was no exception to this trend. Taiwan transformed from a rural society to an

industrial society during the 1970s and 1980s. A growing labor-intensive sector provided

jobs for many women. In the 1990s, the service sector drew even more women into the

job market. Although a gender differential does exist in some kinds of vocation, it makes

no big difference in human capital; the wages of women rise along with their education

level, vocational reputation, and working experience (Chang, 1992; Schumann, Ahlburg,

& Mahoney, 1994). The achievements of working women in turn enlarge their working

areas and ranks, which raises the opportunity cost to quit their jobs, even after marriage

(Change, 1996; Sørensen, 1983). At the same time, this trend also makes it easier for

working women to return to the job market at an earlier time, even if they once withdrew

because of childbirth (Hsueh, 2000; McLaughlin, 1982; Tsay, 1988).

The labor participation rate for women aged 15 to 64 years was 41.90% in 1980

and 54.13% in 2005. To some, it seems that Taiwanese women are not eager to join the

job market, because the labor participation rate rose only 12% in this time. But 12% tells

only part of the whole story. The main reason for this outcome is the expansion of higher

education, which signicantly reduces the labor participation rate. Labor participation

rates of the group aged 15 to 19 years fell quickly from 42.99% in 1980 to 9.85% in 2005.

The group aged 20 to 24 years also started to reverse its upward trend after 1988. Most

70

Women in Taiwan: Socialcultural Perspectives

women in the group aged 25 to 29 years have completed their educations but have not

married or had children, which shows a strong tendency for women to gain employment;

the rate reecting this change rose from 41.27% in 1980 to 77% in 2005. Age groups above

25 to 29 present the same upward trend. Figure 4 illustrates that the age distribution

of female labor participation rates has transformed from an M shape to a normal curve

moderately skewed to the right. The former M shape is the consequence of women usually

quitting from the labor market because of marriage and childbirth and returning to work

only after their children have reached a certain age. A normal curve then means that the

ratio for women’s early withdrawal is declining.

Gender Difference in Education

Taiwan has undergone a period of higher education expansion since the late 1980s.

The number of colleges and universities was only 26 and the net enrollment rate for

tertiary study for people aged 18 to 21 years reached only 10.48% before the early 1980s.

In 2005, these two numbers of colleges and universities had soared to 145 and enrollment

to 58.32%. College education is quite normal for people, even though it is not mandatory.

Figure 4. Female Labor Force Participation Rates, 1980, 1990, and 2005.

Source: MacroEconomics Data Base. The Directorate General of Budget, Accounting and

Statistics. Retrieved November 1, 2007, from http://61.60.106.82/pxweb/Dialog/statle1L.

asp?lang=1&strList=L#

71

5. Changes in Fertility and Marriage Rates in Taiwan

Male college students used to outnumber females in Taiwan, but the number of

female students quickly increased with the emerging notions of gender equality and higher

education expansion. Now, the number of female students has exceeded males. Figure 5

demonstrates this trend: The number of female freshmen students was only 71% of that for

males in 1982, but female students had outpaced male students by 1994. The gures also

show us that the number of female graduate students has grown faster than that of males.

Gender Difference in Wages

The increasing human capital of women and the expansion of the tertiary industrial

sector not only push up female labor participation but also diminish wage differences

between men and women. Figure 6 reveals the average male-female wage differentials for

persons who never married. In 1980, women’s average wages did not even reach 80% of men’s,

but they exceeded 90% in 2005. The wage ratio for women from 30 to 34 years old reversed the

rising trend in 2000. This is because the average marriage age of men, whether disadvantaged

or not, is postponed, which dilutes the weight of socioeconomically disadvantaged men, who

traditionally have not married before the age of 30 years. We can see that wage differentials reach

their minimum in the group aged 35 to 49, in which some women’s wages surpass the men’s.

Figure 5. Sex Ratio of Higher Education Students.

Source: Dataset of Education Statistics, Ministry of Education. Retrieved November 1, 2007,

from http://www.edu.tw/edu_web/edu_mgt/statistics

72

Women in Taiwan: Socialcultural Perspectives

Figure 6. Male-Female Wage Differentials for Persons Who Never Married.

Source: Calculated from raw data of Manpower Survey, The Directorate General of

Budget, Accounting and Statistics, 1978-2005.

Changes in and Persistence of Assortive Mating

As gender differentials in education and income are narrowing, the conventional

pattern of assortive mating may not be as popular as it was in the past. There are two

basic assumptions on assortive mating in sociology. The rst is homogamous marriage

(homogamy), meaning that the most popular mating pattern is the marriage between

people of similar social status. The second assumption is upward heterogamous marriage

(hypergamy) for women, meaning that women are inclined to marry men with a social

status higher than their own.

Both assumptions are based on the approach of social stratication. The rst

assumption reects the constraint of social structure, in which different social strata

have their own value systems and preferences. Homogamous marriage could consolidate

an established social hierarchy and thus retain its stratum characteristics (Goldthorpe,

1980). The second assumption reects the stratication of gender; that is, the role of men

is conventionally higher than that of women, and consequently, men control most social

resources such as property inheritance, educational achievement, occupation, income, and

so on. As a consequence, women have to use their “natural” resources like youth and beauty

73

5. Changes in Fertility and Marriage Rates in Taiwan

to realize upward mobility by marrying “higher” men, and men have to keep their authority

over their families by marrying women from a lower stratum (Lipman-Blumen, 1976).

The relevant research in Taiwan basically supports the assumption of homogamy

and women’s hypergamy (Tsai, 1994; Tsay, 1996). Nevertheless, equality between men and

women advanced signicantly during the last quarter of the twentieth century, especially

after 1990, and will continue in the future. Then, the market for women’s hypergamy could

be reduced and women’s socially downward marriage rates could rise. To document the

changes in women’s socially downward marriages, we examine the responses to the Surveys

of Marriage, Fertility and Employment of Women in 1990, 1993, and 2000. Proles of

education-wage

72

-age assortive mating of three marriage cohorts—those married from

1970 to 1979, 1980 to 1989, and 1990 to 2000—are generated and compared.

The changes in women’s downward marriage are shown in Table 2. We can see that

the growth in women’s downward marriage exists in only one dimension, education, while

remaining roughly the same for age and income patterns.

Table 2. Women’s Downward Marriage by Socioeconomic Indicators and First-

Marriage Cohort

First marriage cohort

women’s downward marriage on

1970s 1980s 1990s

Only one variable 16.82 22.67 24.47

Education 8.13 14.13 15.77

Wage 6.09 6.63* 6.61*

Age 2.60 1.91 2.09*

Any two variables 1.13 2.03 2.40

Education and age 0.64 1.44 1.61*

Education and wage 0.36 0.37* 0.49*

Wage and age 0.12 0.22* 0.30*

All three variables 0.01 0.02 0.07*

Note: Figures in percentage. * p> .05 denotes no signicant difference with previous-

marriage cohort.

A closer analysis shows that the expansion of women’s downward marriage in

education mainly happens at the junior college level, not university level. The proportion

of downward marriages for women above graduate level declines signicantly, as shown in

Table 3, which means that a new generation of highly educated women is no longer willing

to compromise. In other words, highly educated women in the past tended to choose

74

Women in Taiwan: Socialcultural Perspectives

less-qualied husbands rather than spinsterhood if they had to pick only one of those

options, but now, marriage is no longer seen as a necessary stage in life. If we maintain

our conventional rules for marriage, marriage rates will predictably decline along with

the expansion of higher education and relatively increased women’s wages. While the

increasing number of bachelors comes mainly from the less-educated, the increasing

number of unmarried women comes from those who are highly educated.

Table 3. Women’s Educational Downward Marriage by Wife’s Education

Marriage cohort Primary

Junior

high

High College University

Graduate Total

1970–1979 1.37 23.90 15.54 15.82 22.72

43.54 9.43

1980–1989 0.50 15.58 20.13 22.26 23.21*

33.49* 15.67

1990–2000 2.16 6.48 18.71* 27.45 25.83*

18.38 17.52

Note: Figures in percentage. *p> 0.05 denotes no signicant difference with previous

marriage cohort.

The Possible Development of Marriage Rates

If the rate of women’s downward marriage does not increase with the elevation of

women’s social and economic status, marriage rates will likely continue to decline in the

future. Women’s probability of getting married will decrease, and the period for keeping

a spouse will be shorter. To demonstrate a variety of outcomes due to marriage rate

changes, we use single-year age-specic exposure rates to establish a marital status life

table (Schoen, 1975; Zeng, 1993) of Taiwan in 2005, including single, married, divorced,

and widowed status. To display the potential inuence of marriage rates on fertility, the

age limit in the table is 39 years.

73

The changing trend is also illustrated for the past quarter

century by the comparison basis of 1980.

Table 4 reveals that for persons aged 15, the total rst-marriage rate,

74

which

indicates the total number of rst marriages in a synthetic cohort of both genders before

39 years old passing through life together, reached 0.95 or so in 1980 but declined to 0.72

for women and 0.66 for men in 2005. Divorce rates also increased signicantly. Among

100 married males are 18.8 married men who will divorce before 39 years of age in 2005,

and 25 for correspondent women. Both numbers mark a prominent rise compared to the

rate for 1980, which is less than 8%. Also, remarriages from divorces declined 20% for

both men and women. Figures for widows/widowers do not change much.

From 1980 to 2005, the average age of rst marriage is postponed 3.4 years for men

and 3.7 years for women. Generally speaking, the probability of widowhood is quite low,

75

5. Changes in Fertility and Marriage Rates in Taiwan

so it will not be inuenced by the postponement of age of rst marriage. If divorce trends,

meaning the distribution of divorce rates by marriage years, do not change, however, the

average divorce age should be postponed along with the postponement of rst marriage

age. Because average divorce age has not been postponed to the same extent, it is clear

that that the divorce rate in Taiwan is increasing. As we explained above, the remarriage

rate after divorce has declined to only about 30% for the past 25 years. This means that the

majority of divorced people never get married again. Does the rising divorce rate and the

remarriage rate imply that a small portion of people separate and get remarried faster and

more frequently than before? This is an interesting issue for further research.

The average duration of a marriage has reduced to 4.1 years for men and 5.1 years

for women in the past 25 years. Average durations of divorce and widowhood both rise as

remarriage rates for the divorcees and widowers/widows have also fallen.

On the whole, although the average duration of a marriage before the age of 39

years has shortened, it is still long enough to allow for two children being born, even if

we take into consideration the problem of declining fertility due to age. Consequently, a

delayed marriage age or a rising divorce rate should not produce a signicant inuence on

fertility. Rather, a greater threat comes from the shrinkage of the duration of marriages.

Because childbearing out of wedlock is still not acceptable in Taiwanese society, the data

in Table 4 imply that fertility is likely to decline further. Many people therefore call for the

promotion of marriage. Unfortunately, as we have discussed before, the rate of women’s

downward marriage does not appear to increase as women lift their socioeconomic status.

Women will likely prefer to be single rather than enter a downward marriage; there should

therefore be a better way to concentrate resources on promoting the fertility of married

women, especially women on the high-fertility incline.

Women’s Work Lifestyle and Social Policy

For contemporary women, entering into marriage no longer has to be destiny, and

childbearing is not a necessity. Life development for women has become more and more

diverse. Hakim (2000) puts women’s lifestyles into three categories: adaptive, work-

centered, and home-centered. Adaptive women, which account for the majority of women,

are those with children and a career. They want to attach equal importance to family and

job. Their investment in occupational training is often taken as a strategy of insurance

for unemployment. Work-centered women are usually full-time working (married or

unmarried) women without children. Although this type of woman is not the majority, the

proportion is getting higher. Like most men, these women focus on market competition

76

Women in Taiwan: Socialcultural Perspectives

and public affairs. Because their eager devotion in the job market is not for insurance but

for further development of their professions, these women keep higher labor participation

rates than the other two types. Home-centered women are full-time household workers,

and their proportion is in decline. Women of this kind prefer to concentrate on their

husbands and children. Their education levels are not necessarily lower than for the other

two groups, but the goal of education investment is to match their “ideal hubs” in a higher

socioeconomic status. For these women, entering the job market is usually a choice made

when there are no other, better, alternatives. Not surprisingly, these women have the

lowest labor participation rate.

In the face of this diversication of women’s life development, Hakim reminds us

of the necessarily diversied responses. Different kinds of women will have different

reactions to the same policy. Take a birth-promotion policy as an example: Home-

Table 4. Marital Status Life Tables up to 39 Years of Age, 1980 and 2005

Summary measures Male Female

1980 2005 1980 2005

Probability a person age 0 will ever marry 0.919 0.657 0.933

0.713

Probability a person age 15 will ever marry 0.940 0.664 0.950

0.719

Meanageatrstmarriage 26.59 29.98 23.68

27.38

Number of marriages per person marrying 1.042 1.061 1.055

1.097

Probability of transfer from state i to state j

single —> married 0.940 0.664 0.950

0.719

married —> widowed 0.016 0.007 0.037

0.022

married —> divorced 0.067 0.188 0.076

0.251

widowed —> married 0.336 0.351 0.323

0.333

divorced —> married 0.533 0.301 0.553

0.344

Mean age (years) at transfer from state i to

state j

single —> married 26.59 29.98 23.68

27.38

married —> widowed 33.80 34.68 32.73

33.95

married —> divorced 32.23 32.40 29.95

29.81

widowed —> married 33.59 35.11 32.29

33.29

divorced --> married 33.70 34.07 31.98

31.31

Average duration (years) of a

Marriage 11.889 7.837 14.270

9.160

Widowhood 3.052 3.174 4.841

4.980

Divorce 4.130 5.415 5.358

6.846

77

5. Changes in Fertility and Marriage Rates in Taiwan

centered women are willing to have more children and thus should be the main target of

this policy. The election of childbearing for work-centered women is not easily inuenced

by policy, so there is no need to apply policy resources toward them. Adaptive women

usually burn the candle at both ends; without adequate help from government, more and

more women from this group will turn to the work-centered approach. This will make a

birth-promotion policy even harder to support.

Currently, most social policies in Taiwan emphasize dealing with the problems of

adaptive women. As the status of home-centered women is in decline, they receive scant

attention in the application of social policy. As a matter of fact, full-time mothers are still

an ideal arrangement for childcare and deserve encouragement in terms of the benets

for children. Today, parental leave and subsidies for childcare in many countries offer

no help for full-time mothers. The reason is clear: If women do not work before they give

birth, they will not have any parental leave. They also cannot acquire any subsidy for

children because they take care of the children themselves. Compared to work-centered

women, home-centered women are in a disadvantaged position in family policy. To solve

this problem, countries in Europe in the 1990s started to provide a homecare allowance,

which provides a certain amount of money for those (mothers or fathers) who take care of

young children to compensate for their loss in the job market. Finland, for example, offers

an allowance equal to 40% of the average wage of female employees for taking care of each

new arrival (Hakim, 2003, p. 168).

Although the problem of burning the candle at both ends for adaptive women has

been the concern of social policy, housework outside of the intervention of social policy

is still imposed on women. In the process of social change, the egalitarian attitudes of

women usually develop faster than those of men. Those women who live in a society with

a history of high gender stratication thus have a stronger demand for equal division of

labor for housework (Banaszak & Plutzer, 1993). If economic development requires the

employment of female labor but the society does not react to the changing role of women

institutionally and culturally so as to satisfy an equal division of labor in housework, it will

probably bring about a long-term fall in marriage and birth rates. As a scholar (McDonald,

2000) recently pointed out, the lowest level of low fertility in southern Europe is a

consequence of signicant progress in gender equity in individual-oriented institutions

and slow progress in gender equity in family-oriented institutions, so resolution of the

conict over the focus on both family and work cannot be concentrated solely on full-time

working women; we need to induce more men to participate in housework. Sweden’s forced

fatherhood,

75

designed especially for men, is a good idea worthy of recommendation. In

78

Women in Taiwan: Socialcultural Perspectives

the last stance, a basic way is perhaps to provide proper gender education commencing

when people are youngsters.

Conclusion

The TFR in Taiwan was below the replacement level in 1984. In the 20 years since

then, it uctuated at around 1.75. Another downward trend started in 1997, and the TFR

sank to 1.12 in 2005, a level called the lowest of low fertility. Contrasting age-specic

fertility rates with age-specic marital fertility rates, we found that the newest change of

fertility is caused by the fall in the proportion of the population currently married in all

age groups. This fall has much to do with the rising socioeconomic status of women. Since

World War II, women have made signicant progress in education, the job market, and

income. In terms of the number of enrolled students in higher education and the wages

of single people, gender differentials are getting smaller and smaller. Nevertheless, the

marriage market does not reect this change and still maintains conventional models of

homogamy and women’s hypergamy. As the conventional assortive mating pattern starts

to diminish, what has been induced is not women’s downward marriage but ascending

bachelorhood (for both genders). If age-specic marriage rates continue on their current

courses, 30% of women will never get married before the age of 39 years. As Taiwan has not

widely accepted births outside wedlock, it appears inevitable that fertility will keep falling.

Apparently, for contemporary women, a marriage does not have to be destiny,

and childbearing need not be a necessary requirement either. Life-development options

for women have become more and more diverse. Hakim (2000) puts women’s life

development into three categories (adaptive, work-centered, and home-centered) and

points out that social policy must apply different strategies for different kinds of women.

This is a good reference point for Taiwan in the process of building up its social policy.

As we agree that women should devote time to their careers, we should not overlook

the importance of women undertaking traditional roles. As work-centered women have

been the mainstream model, the status of home-centered women is getting lower and

attracting less policy concern. It seems that while we are breaking the cage for women,

we paradoxically create another. Meanwhile, McDonald (2000) poses a good point

about unmatched development of gender equity in individual-oriented institutions and

in family-oriented institutions, which implies that women might be more willing to give

birth when men are more willing to share housework.

79

5. Changes in Fertility and Marriage Rates in Taiwan

References

Banaszak, L. A., & Plutzer, E. (1993). Social bases of feminism in Europe. Public Opinion

Quarterly, 57, 29–53.

Becker, G. S. (1991). Treatise on the family. (enlarged edition). Cambridge, MA: Harvard

University Press.

Chang, C. C. (1992). Determinants of labor wage in Taiwan. Bulletin of Labour Research,

2, 111–126. [in Chinese]

Chang, C. F. (1996). The natal and marital reasons for withdrawing from the labor

market for female workers. Paper presented at the meeting of Institute of

Sociology, Academia Sinica, Taipei. [in Chinese]

Clarkberg, N. M. (1999). The price of partnering: The role of economic well-being in

young adults’ rst union xxperiences. Social Forces, 77, 945–968.

Goldscheider, F. K., & Waite, L. J. (1986). Sex difference in the entry into marriage.

American Journal of Sociology, 92(1), 91–109.

Goldthorpe, J. H. (1980). Social mobility and class structure in modern Britain. Oxford:

Clarendon Press.

Hakim, C. (2000). Work-lifestyle choices in the 21st century: Preference theory. Oxford

University Press.

Hakim, C. (2003). Preference theory: A new approach to explaining fertility patterns.

Population and Development Review, 29(3), 349–374.

Hsueh, C. T. (2000). An exploratory analysis of the timing of job reentry for married

women in Taiwan. Journal of Population Studies, 21, 77–99. [in Chinese]

Lee, M. L. (1994). Population changes of marital status in Taiwan during the twentieth

century. National Taiwan University Journal of Population Studies, 16, 1–14. [in

Chinese]

Lipman-Blumen, J. (1976). Toward a homosocial theory of sex roles: An explanation

of the sex segregation of social institutions. In M. Blaxall & B. Reagan (Eds.), The

women and the workplace (pp. 15–32). The University of Chicago.

McDonald, P. (2000). Gender equity in theories of fertility transition. Population and

Development Review, 26(3), 427–439.

McLaughlin, S. D. (1982). Differential patterns of female labor force participation

surrounding the rst birth. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 44(2), 407–420.

Ministry of Education. (2007). Dataset of education statistics. Retrieved November 1,

2007, from http://www.edu.tw/edu_web/edu_mgt/statistics

Ministry of Interior. (various years). Taiwan-Fukien demographic fact book.

80

Women in Taiwan: Socialcultural Perspectives

Moftt, R. A. (2000). Female wages, male wages, and the economic model of marriage:

The basic evidence. In L. J. Waite (Ed.), The ties that bind: Perspectives on

marriage and cohabitation (pp. 302–319). New York: Aldine de Gruyter.

Ono, H. (2003). Women’s economic standing, marriage timing and cross-national

contexts of gender. Journal of Marriage and Family, 65, 275–286.

Oppenheimer,V. K., & Vivian, L. (1995). American marriage formation in the 1980s:

How important was women’s economic independence. In K. O. Mason & A. M.

Jeansen (Eds.), Gender and family changes in industrialized countries (pp. 105–

138). Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Pampel, F. C., & Tanaka, K. (1986). Economic development and female labor force

participation: A reconsideration. Social Forces, 64(3), 599–618.

Schoen, R. (1975). Constructing increment-decrement life tables. Demography, 12(2),

313–324.

Schumann, P. L., Ahlburg, D. A., & Mahoney, C. B. (1994). The effects of human capital

and job characteristics on pay. Journal of Human Resources, 29(2), 481–503.

Shryock, H. S., & Siegel, J. S. (1976). The methods and materials of demography.

Washington, D.C.: The Government Printing Ofce.

Sorensen, A. (1983). Women’s employment patterns after marriage. Journal of

Marriage and the Family, 45(2), 311–321.

The Directorate General of Budget, Accounting and Statistics. (2007). MacroEconomics

Data Base. Retrieved November 1, 2007, from http://61.60.106.82/pxweb/Dialog/

statle1L.asp?lang=1&strList=L#

Tsai, S. L. (1994). Assortive mating in Taiwan. Journal of Social Sciences and

Philosophy, 6(2), 335–371. [in Chinese]

Tsay, C-L. (1988). An elementary analysis of re-entry of the female labor force. Taiwan

Economic Review, 16(2), 149-174. [in Chinese]

Tsay, R. M. (1996). Who marries whom? The associations between wives' and husbands'

educational attainment and class in Taiwan. Proceedings of the NSC, Part C:

Humanities and Social Sciences, 6, 258–277.

Zeng, Y. (1993). Methods and applications of demographic analysis. Bejing University

Press. [in Chinese]

____________________

Notes

68. According to Taiwanese custom, a tiger year is an unlucky year. Those who are born

in a tiger year will suffer ill fate; therefore, most people avoid giving birth in tiger years.

81

5. Changes in Fertility and Marriage Rates in Taiwan

People are also reluctant to accept a tiger bride (but tiger grooms are not too bad

bygeneralopinionbecausetheytthemasculineimageinapatriarchalsocietylike

Taiwan). It is also believed that marriage in a “year of loneliness” will end in divorce.

69. As the dragon is considered the symbol of power and prosperity, people prefer to

have dragon children.

70. Data for marital fertility rates were not collected until 1965.

71. The unreasonable gure of AMFR for those aged 15 to 19 years in 2004, 1290 births

per1000marriedwomen,isduetotheconventionaldenitionofmaritalfertilityrate.

Because births out of wedlock were not acceptable and were therefore rare in the

past, the ratio of total number of births to married women has become a proxy of the

marital fertility rate in demographic statistics for most countries (Shryock and Siegel,

1976). Obviously, this conventional operation is not suitable in Taiwan, at least for

teenagers.Togeneratecorrectage-specicmaritalfertilityrates,weneeddatasets

of fertility history, known as the KAP-survey series in Taiwan. Unfortunately, the sample

sizesofKAPsurveysaretoosmalltogenerateage-specicmaritalfertilityrates.Also,

15- to 19-year-old married women were not included as interviewees in surveys for

a long time. Therefore, although the rates for women aged 15 to 19 years appear

exaggeratedrecently,westillfollowtheofcialrecordstoindicatethetrendofage-

specicmaritalfertilityrates.

72. The educational achievement and wage used here refer to their levels when a survey

was held rather when the women were married. To be sure, the levels indicated when

thesurveywashelddonotdenitelycorrespondtothelevelsduringmarriage.Thinking

the other way around, however, people will not only evaluate the income ability for

now, but also that in the future when they consider their potential partners. To a large

extent, a current wage could reect the tendency of future wages if we go back

to the time when respondents just got married. Meanwhile, focusing on currently

married respondents also causes a statistical problem—screening out those who were

divorced. Nevertheless, when wives’ wages are much more than their husbands’, they

have a higher divorce possibility. The other side of the same coin is that the current

stable couples represent the persistence of “adequate” mating.

73. Although fertility age is generally dened from 15 to 49 years, the fertility rate of

Taiwanese women above 40 years old is almost close to zero. We therefore terminate

at 39 years old.

74. TheTFMR,denedbythenumberofmalesorfemaleswhowillevergetmarriedper

1,000malesorfemalesinapopulation,isobtainedbysummingupage-specicrst

marriage rates.

75. All Swedish working parents are entitled to 18 months’ parental leave with or without

familybenetsfromthebirthofthechild.Inaddition,theyhavearightto480days

of paid leave per child, the cost being shared between employers and the state. To

encourage greater paternal involvement in child rearing, a minimum of 2 months out

of the 18 is required to be used by the "minority" parent, in practice, usually the father.