Character Design: a new Process and its Application in a Trading Card

Game

Jo

˜

ao Ramos da Silva Filho

∗

Liandro Roger Mem

´

oria Machado

†

Natal Anacleto Chicca Junior

‡

Artur de Oliveira da Rocha Franco

§

Jos

´

e Gilvan Rodrigues Maia

¶

Federal University of Ceará,

Virtual University Institute, Brazil

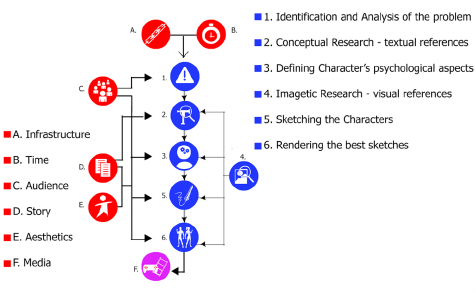

Figure 1: Stages of the proposed character design process (a). Candidate sketches for exploring variations (b). In this case, the product consists

in a character for a Trading Card Game (c).

ABSTRACT

Creating characters is a practice which origin is closely related to

aspects of human society such as myths and religion. The creation

of characters has become an important process not only for visual

and literary arts but it is undoubtedly an important process for the

entertainment industry. Character Design as utilized in the industry

is a process that occurs alongside with other background processes.

Products developed by adopting these process are bound to many

specifications and different medias. Unfortunately, most develop-

ments on such processes are restricted to companies that typically

display a distant or superficial relationship with the academy. This

usually prevents further analysis and subsequent optimization of

these processes. This work proposes a Character Design process

conceived for a wide range of applications. We applied the pro-

posed process in a case study where the final product is a set of

card illustrations for a Trading Card Game prototype inspired by

Brazilian myths.

Keywords: Character design, concept art, processes, trading card

game.

1 INTRODUCTION

Character Design has been an important part of human society since

ancient times. The advent and dissemination of myths and legends

inspired society throughout centuries with characters that instigated

∗

e-mail: joaofilho[email protected]

†

e-mail: [email protected]

‡

e-mail: [email protected]

§

e-mail: arturoli[email protected]

¶

e-mail: gilv[email protected]

the innermost feelings of people [1]. Through developing a system

of storytelling, people started to create characters as transcenden-

tal beings that personify ideas which inspired and influenced the

upcoming generations of human society in many different ways.

As technology advanced, a multitude of media to demonstrate

and propagate ideas were created as time passed and cultures

evolved. Characters of different cultures have different visual repre-

sentations in different medias and, because of that, creating original

character design might be very difficult [17] [14] [7]

Designing a good game or movie character requires more than

only having an idea nowadays. In order to create a coherent and

consistent character design an artist needs to consider the many re-

strictions and to develop a suitable work method. Accomplishing

this task requires more than only knowing how to represent things

graphically.

Unfortunately, there are few academic books and articles about

Character Design. As this task is an inherent part of the industry,

many artists focus on learning the processes in order to apply them

to a product instead of scrutinizing these processes and spreading

new developments in the academic field [4] [8]. In fact, there is

plenty of informal material about design processes on the Web

1 2

3

while their academic counterpart is scarce or outdated.

Moreover, in the few references we could find in the present in-

vestigation, most works focus on the technique over the process

[16], or solely on the concept behind the design [9], or even revolve

around the product itself [10].

In this paper, we present a new character design process. These

are our main contributions:

• We propose and describe, in detail, a character design process

which unifies technique and concept. This process and the

1

http://www.gamasutra.com/

2

http://www.ign.com/

3

http://www.kotaku.com/

SBC – Proceedings of SBGames 2016 | ISSN: 2179-2259

Art & Design Track – Full Papers

XV SBGames – São Paulo – SP – Brazil, September 8th - 10th, 2016

547

results from experimentation are shown in Figure 1.

• We demonstrate the use of the proposed process in a case

study.

The remaining of this paper is organized as follows. Background

definitions about character design and its underlying production

processes are covered in Section 2. The proposed character design

process is introduced in detailed throughout Section 3 and then it is

assessed through a case study whose development occurred adopt-

ing the proposed process, as described in Section 4. Finally, con-

clusions about this work and its future research opportunities are

discussed in Section 5.

2 BACKGROUND

Historically, the human mind tries to fill the blank spaces of reality

with the fantastic and the supernatural [14] [1]. Therefore, myths

were created with the purpose to explain natural phenomenon or hu-

man condition and the myths ended up becoming a part of society,

creating traditions and festivals. These cultural elements became

stories that were passed from one generation to another, creating

what William J. Thorns, under the pseudonym of Ambrose Merton,

called folk-lore, the knowledge of the people [13].

The influence of the supernatural in the human society modeled

the way people act and live. In no time, monsters and gods that once

were in temples and forests migrated to video games and movies,

which helped to popularize the various legends and mythologies

around the world [7] [14].

2.1 Creating Stories

Pagan stories suffered big losses due to competition with the dom-

inant religions at the time and also ignorance, but arts have en-

countered a way to save some aspects from pagan religions. On

the twentieth century, the entertainment industry rises with great

books, movies and specially games productions and many of those

get mythological context and aesthetics, like the modern game God

of War

R

or the books, movies and games about Middle Earth [6]

[12] [2].

Stories that inspire people, however, are not made without an

element which people can relate to. This element is commonly a

character. According to Bartlett [1], gods and goddesses described

in myths are a representation of feelings and situations that people

can correlate to. Personificating a concept turns the divine under-

standable and close to humanity.

Nowadays, reaching the divine is not the main focus of most

stories, but the fantastical element still resides there. This element

is used to enhance the product attractiveness for a target audience

[12]. Clever usage of archetypes for constructing characters that

are both consistent and coherent also helps to increase the products

appeal for the general public [3].

Although video games were not the sole entertainment form that

contributed to spread myths around the world. In 1993, the first

Trading Card Games (TCGs) appeared, mostly due to the company

The Wizards of the Coast, which was one of the pioneers in the TCG

industry by publishing the iconic title Magic: The Gathering that

became popular worldwide. In 1999, the same company published

Pokemon - Trading Card Game, which consolidate the success of

TCGs on the market [5].

Various mythologies and cultures were spread worldwide

through different games and movies inspired by their stories. How-

ever, some cultures naturally stood out and such highlight ended up

casting a shadow over other cultures. For example, despite being

fulfilled with fascinating myths and legends, the Brazilian culture

is still unknown to most people around the world and even the coun-

try itself.

Attempts to popularize Brazilian legends and myths rarely suc-

ceeded. It is observed that the representations of those cultural traits

are not accurate and, moreover, productions are mostly targeting

children as their audience. This is noticed in the TV Show S

´

ıtio do

Picapau Amarelo, produced in 2001. However, even on successful

attempts to represent and promote Brazilian folklore, the character

design process is clearly far from being fully explored.

Comprehension about the underlying concepts that support the

product and what techniques are used to create the final product

play a key role in understanding what is character design and why

it is important for game development.

2.2 Concept Art

A draft composed by a storyline and an initial concept of how the

product will be are usually created as the first step of the game de-

velopment process. From those early ideas it comes what is known

as Concept Art or Concept Design. It is on this step where a myriad

of possibilities for the final aesthetic aspects of a game are pro-

duced, chosen and tuned [15].

Concept Art is the type of art which main focus is to represent

an idea graphically in order to help the development of a product.

[Concept art is the] art capable of translate or sell an idea, capable

of represent it in a way that a story can be read [19]. Concept Art

involves the creation of characters, environments and stories that

help to demonstrate how that idea could be implemented and in-

tegrated to the final product. Dozens of ideas and rough sketches

are typically made focusing diversity and quantity to obtain a single

satisfactory result, for example. Therefore, it is clear that this task

can benefit from adopting an adequate development process given

the enormous effort necessary to accomplish it.

Figure 2: Concept Art and its four main areas, considering the work

developed by visual artists.

According to Takahashi e Andreo [15], concept art involves dif-

ferent types of development, such as development of characters,

accessories, and environments. Those different types of design in-

serted on concept art can be separated in four main areas: Charac-

ter Design, Creature Design, Environmental Design, and Industrial

Design. These are depicted in Figure 2.

Due to the existence of a handful of other design fields that are

well known, such as Costume Design and Sound Design, this divi-

sion considers the products conceived by visual artists as it is also

commonly observed in a multitude of both job descriptions

4

and

artists blogs and portfolios

5 6 7

.

When designing a product, artists explore different possibilities

in order to make sure that the most effective and efficient choices

are being made. Exploring the possibilities requires knowledge

4

https://www.artstation.com/jobs/gNo

5

http://www.raphael-lacoste.com/

6

http://andrewdoma.blogspot.com.br/

7

http://www.robotpencil.org/

SBC – Proceedings of SBGames 2016 | ISSN: 2179-2259

Art & Design Track – Full Papers

XV SBGames – São Paulo – SP – Brazil, September 8th - 10th, 2016

548

about different areas. Although there are no real products being

physically produced, artists need to make all the elements in the de-

sign look as believable and compelling as possible for the general

public. Therefore, the four design areas within concept art sum-

marize the requirements for creating realistically designs applied

to the elements within the movie or game undergoing a production

process.

2.3 Character Design

The area inside Concept Art that concerns the creation of characters

is known as Character Design. It is through the Character Design

that physical and psychological characteristics are presented, giving

the character depth and making it connect with audience [14] [8].

In order to achieve a satisfactory result, a character designer needs

to do more than draw and paint a beautiful image.

According to Bryan Tillman [17] what makes a good character

design is the combination of story, narrative, archetypes, shapes,

silhouettes and aesthetics. This combination gives the character be-

ing created more than just a good look: this gives it life in order to

convince an audience and get their approval.

From the development process, character design is composed of

several stages connected to each other. Creating a character is the

same as create a living being with feelings, history, dreams, per-

sonality etc. Because of that, the artist has two different general

approaches to create a character. One is linked to the story and psy-

chological aspects of the character, while the other is focused on

the visual composition of the character. Seegmiller [14] refers to

the former approach as Storytelling while Tillman [17] refers to the

latter as Aesthetics. Both aspects are important to create a coherent

and consistent character once understanding how the character acts

and how it looks like, will facilitate the creation of several sketches

and possibilities [8] [7]. By doing so, the artist can produce faster

and more accurately than when they only focus on a single task.

Focusing only on the Storytelling approach in a product that needs

to be visual will not lead the artist further or faster, while focusing

only on Aesthetics will turn the character overly shallow.

2.4 Character Design Processes

Character Design is composed of different stages that facilitate the

efficient creation of characters. The process applied in this paper

requires a considerable amount of creativity from the artist and

that might lead to stressful situations that can prejudice the project.

Having an specific plan of how to work will not only increase the

productivity, it will also decrease the level of frustration [14]. It is

worthy to understand how stressful it can be for the artist when she

is working for a company or a client which impose hard deadlines

as well as various requirements and restrictions.

Seegmiller [14] presents a character design process composed

of five iterative steps: (1) Problem Identification, (2) Analysis and

Simplification of the Problem in which ideas are generated, (3)

Choose the Best Ideas, (4) Drawing of the Character, and (5) Eval-

uating the Results. Although these steps are logically correct and

consistent, the actual steps applied in the process may vary from

artist to artist and these may also change according to the project.

Seegmiller also states that following the 5 steps, even modified, is

almost certain that the design will be successful.

Bryan Tillman [17] describes Character Design as a combination

of different elements. These elements are the psychological and

physical aspects of the character and the story that revolves around

it. The author separates Character Design into Archetypes, Story,

Originality, Shapes and Forms, Aesthetics, and the Wow Factor.

Tillman also emphasizes how using references and thinking about

the target audience are important to create a good character design.

The steps proposed by Seegmiller comprise a work method,

while Tillman, in his turn, explores the conceptual part of the pro-

cess. Both approaches are of uttermost interest for practitioners as

these can lead to results in a more predictable fashion. However,

we advocate that there is room to improve those Character Design

processes. In short, we strive for a unified approach for Character

Design, referring to it as a process that combines appealing features

from both approaches presented by these authors.

3 PROPOSED CHARACTER DESIGN PROCESS

During the creation of a product, there are many stages of devel-

opment. It is during the first stage, when the concept of the whole

product is being created, that Concept Art takes place [15]. The vi-

sual designs of such product are obtained throughout Concept Art

and they affect directly all the other production stages.

It is important to understand that Character Design refers to an

idea instead of a style or aesthetic. Some artists use the cartoon art

style to demonstrate emotions more clearly in characters because

this specific style is based on exaggerating features and expressions

making them easier to be visually perceived. However, character

design is not bound to this art style. Moreover, an adequate Char-

acter Design process requires flexibility and has different stages or

methods that may vary from artist to artist according to the projects

requirements.

For instance, let’s examine character design applied to anima-

tions. As described in InformAnimation IP Handbook 2011 (p.109)

[18], the process of Character Design is divided into three stages:

Research and Development, Finalized Visual Design and Defining

the Performance. Each stage focus on what should be produced for

a specific part of the project. Furthermore, this process ends up be-

ing mechanized. If the reader is not careful enough, he or she might

not understand all mechanisms and processes comprising the inner

working of this process.

In order to present a method that works in different situations,

we took the 5 steps proposed by Seegmiller [14], and we expanded

them to be as inclusive and flexible as possible by also consider-

ing insights from the process proposed by Tillman [17]. For that

to come true, all processes that restrict and mold a game or movie

story need to be understood. Nonetheless, the Character Design

as we propose works with two different types of processes. Back-

ground Processes are restrictive processes, they define what course

the design should follow in order to accomplish a satisfactory re-

sult in accordance with the script or story previously defined. Fore-

ground Processes, in their turn, refer to the artists perspectives, their

work method and ability to work under restrictions.

Having that in mind, 6 steps were defined for the foreground

process or Character Design: (1) Identification and Analysis of the

problem, (2) Conceptual Research - textual references, (3) Defining

the Characters psychological aspects and (4) possible appearances

by means of Imagetic Research, (6) Sketching the Characters, (6)

Rendering the best sketches. It is expected that coherent and con-

sistent characters will come out after following these steps . As

for the background processes we have 6 elements relating to the

foreground steps: (A) Infrastructure, (B) Time, (C) Audience, (D)

Story, (E) Aesthetics, (F) Media. This is depicted by Figure 3.

3.1 Background Processes

Development of modern products involves different stages and a

handful of professionals. In products that involve the creation of a

story it is commonly required to design characters for that particular

product. A professional character designer usually works with a

team of professionals of different sectors of the company in order

to understand the needs of each sector [3] [9]. Unfortunately, this

kind of reality does not apply to every situation. When there is not

a proper communication among the development team, all people

involved might be in for a long and stressful project or it would be

a very short relationship [14].

Be it a personal project or a project in a company, creative artists

must understand that the project is not free from restraints. These

SBC – Proceedings of SBGames 2016 | ISSN: 2179-2259

Art & Design Track – Full Papers

XV SBGames – São Paulo – SP – Brazil, September 8th - 10th, 2016

549

Figure 3: The proposed character design process considers two

main aspects: Foreground processes that obey restrictions posed by

Background processes. This setup gives artists a solid work method

that helps fitting their artwork into a product.

restraints affect directly on the design of the character in order to

induce the artist to create a design that gracefully fits to the final

product. Nonetheless, these restrictions operate in the background

of any product development, hence the choice to classify them as

Background Processes.

Background and Foreground processes are intrinsically intercon-

nected since the first processes offer the base for the latter creat-

ing guidelines followed by the artists. Therefore, such character

design process strongly depends on the Background Processes be-

cause they mold what should enter or not on the final version of

the product. This avoids unnecessary development that drifts away

from the project’s goals.

In order to compose a good character whose design is coherent,

consistent and matches the purpose of a project, an artist must un-

derstand a number of different aspects of the project, in both physi-

cal and conceptual aspects. Physical aspects are related to the work

environment and technology limitation, while Conceptual aspects

relate to the abstract aspects that concern the product such as story,

audience, art style, etc. These elements will be referred as briefing.

Seegmiller [14] and Tillman [17] point several questions that an

artist should think about when coming up with a design. Although

both authors have a different approach, they point out relevant top-

ics for a Character Design in regards of the background processes.

The Briefing consists on the combination of a series of questions

envisioning the overall definition of the product being developed.

It takes in consideration the conceptual aspects divided into Story,

Audience and Aesthetics, described in the following manner.

3.1.1 Conceptual Aspects

Story. The story element provides vital information that gives

depth to the character and define its motivations. Throughout the

story is that the character gains more experience and discover valu-

able information that helps it on its goals. The element Story in-

volves not only the narrative but it also involves the scenario the

revolves the characters. Nonetheless, the element Story establishes

the characters motivations and profile provided by the narrative and

the characters visual aspects provided by the scenario. Deviate from

the story breaks the character cohesiveness within the project.

Audience. One important requirement for creating a character

is knowing to whom it will have to appeal [14]. The audience is

the public that consumes and support a certain type of product or

idea. However, the character designer does not need to appease

only the final public. The artist must design characters that satisfy

the Creative Directors, Writers, Lead Artists and whoever is leading

the project. This way, the element Audience relates not only to the

public but also the project’s producers.

Aesthetics. According to Tillman, the public looks for an ap-

pealing design. Aesthetics is the element that provide guidelines to

compose an appealing character design. Per definition, aesthetics is

associated with beauty, art and taste [17]. Therefore, it is translated

as the element inside the project that defines what art style should

be applied in the final design. Usually, this parameter is created by

Lead Concept Artists and the Art Directors, if the artist is working

for a company.

3.1.2 Physical Restraints

Infrastructure. Artists are deeply bound to their work environ-

ment. From the tools to the co-workers, every aspect of the ambient

the artist is inserted in counts. The technology used in the project

dictates until where the artist can go with complex designs. Not

all computers have enough RAM memory or video memory to sup-

port larger and detailed files. Also, Seegmiller [14] points out that

Character Designers work with 3D Modelers, Animators and Pro-

grammers, and these professionals work within limitations to make

the design presented by the Concept Artists appear in the final prod-

uct. Another element that still constrains the design and creativity is

the budget of the project. Its valid to remember that a professional

character designer does not work for free, and the company needs

to profit out of the product.

Time. Projects do not last forever, so the artist is bound to a

deadline. The time is defined by the scope of the project, the qual-

ity that is expected, and the budget. Time probably defines how

an artist will design a character, technique wise, more than other

constraints. In the industry, time is money. If the artist doesnt de-

liver the concept in time, it might cost a lot for the company and the

artists themselves.

Media. Products that make use of characters and storytelling

are usually a game, a movie, or a comic book or a product that

is related to one or more of them. Furthermore, these categories

utilize different media to host the final product. The element Media

is the parameter that defines the format in which the product will be

published. The actual design may change drastically depending on

the format.

3.2 Foreground Processes

Character Designers have different work methods to solve the same

problem. In the process of exchanging information that was in a

text or script to a graphic media, tons of ideas and sketches are

produced [2] [8]. The proposal of five steps by Seegmiller[14] for

creating a good character design assumes that work methods change

depending on the situation and the artist. Usually, artists that work

in the industry do not document their processes, and for this reason,

there are not many materials regarding this matter. Nonetheless,

the lack of proper documentation has proved to be a great barrier

for artists looking to have a better understanding of the Character

Design process.

Having that in mind, we propose a process that both modifies

the five steps proposed by Seegmiller and combines them with the

conceptual approach of Tillman, while focusing on the application

of the method instead of just explaining separated aspects of the

process. Takahashi and Andreo [15] present techniques that can be

used to create a character and different aspects that are related to

concept art and character design. However, actually, it is hard to

find proper material that gathers the different elements that com-

pose the Character Design and demonstrate or talk about how to

combine technique and concept.

Designing a character requires more than technique: it requires

learning. The process described on this paper offer a viewpoint

where technique and knowledge are combined in a cycle of learn-

ing experience. Through this cycle, artists can improve their profes-

SBC – Proceedings of SBGames 2016 | ISSN: 2179-2259

Art & Design Track – Full Papers

XV SBGames – São Paulo – SP – Brazil, September 8th - 10th, 2016

550

sional skills and the consistency and cohesiveness of their designs.

Using the five steps proposed by Seegmiller as a guideline, we di-

vided the process in six iterative steps: Identification and Analysis

of the problem, Conceptual Research - textual references, Defin-

ing the Characters psychological aspects and possible appearances,

Sketching the Characters, Rendering the best sketches.

3.2.1 Identification and Analysis of the problem

As the name suggests, the first stage consists on identifying and un-

derstanding a problem that corresponds to the requirements of the

character that the artist must understand in order to design it. It is

common that people rush headfirst into creating a design without

understanding the concept of it, and as result, the final design is

flawed and inconsistent [14]. Tillman [17] also states that, by creat-

ing a character without story or without knowing the basic require-

ments, the artist will have to go back and redesign it from scratch.

If this situation is applied in the context of the industry, time cannot

be wasted and such reckless behaviour would not be accepted.

Seegmiller segments this step into two different sub-steps, iden-

tifying and understanding the problem and analyzing the problem.

The former concerns with the general understanding of the ques-

tion at hands, while the latter concerns about further researching

and a breakdown of the elements in manageable pieces. Both steps

are undeniably fundamental for composing the bigger picture, the

project. On this paper, however, we decided to put both steps under

the same stage. Our objective is to describe a method instead of

giving an explanation.

To identify what the problem is and to further analyse it, the

artist needs to understand the conditions that are given to her. This

problem usually is the final objective that needs to be fulfilled. A

character creation must occur within certain parameters to influ-

ence a certain audience according to a certain art style. Therefore,

the artist must bear in mind that the real objective is to understand

and work within the limitations given by the project managers and

creative directors. It is in this stage where the artist becomes aware

of the background processes that will surround the project.

The character designer will analyse each topic and specification

given to him or her in order to get a better understanding what is

expected from his or her artwork. The artist must read what is be-

ing required by each element of the background processes, then the

artist will have a better understanding of the work environment, the

teammates, the budget, the deadlines of the project, the art style re-

quired, the story and specifications of the characters and the media

the character will be released. Based on that analysis, the artist will

develop an efficient and creative work method to construct a suit-

able character design. The creativity must be always pushed far,

especially with todays technology.

3.2.2 Conceptual Research - textual references

As soon as the artists finish planning their work method, they start

to research what they can about everything related to the character.

From simple texts on blogs to historical documents, every piece

of information that might give the artists any insight to design the

character is investigated. But most importantly, the artists need to

have focus. Nonetheless, character designers read the story devel-

oped by the writers once. Through the script is that the artists find

their way to research with more focus. Absorbing a great quantity

of information might not always be helpful.

The use of references to build a character is extremely impor-

tant [17]. References are a crucial aspect, and should not be taken

lightly, especially when these references are textual. Legends and

fables were created having a real story as basis, and the myths are

also a way to understand the reality [1]. During many centuries, sto-

ries were told and written, leaving the construction of the character

for the imagination of the audience. Now, thanks to diverse mech-

anisms that allow stories to be represented visually, the audience

does not have to play the role of character designer anymore [14].

Although, the audience have their own perception of the character,

so the artists must always take that into consideration. Moreover,

the story is still there, under the many layers of graphics and visual

effects, guiding the actions and events.

A written story still holds the keys to trigger our imagination.

This stimulus facilitate the exploration of different designs and pos-

sibilities. On the other hand, manuscripts and books also provide

to the artists some aspects of the real world and its artifacts that can

be used in the product. Using both aspects of the written media, a

character designer has basis and confidence enough to create a char-

acter that works within the limitations and that correlates with the

audience. A concept artist mainly work with concepts, therefore,

Character Designers must know how to transmit ideas through their

designs.

3.2.3 Defining a Character - psychological aspects and role

A character is a person. Even though this sentence might sound

strange, it is the simplest way to understand what a character is.

Characters possess unique characteristics and a story of their own,

with memories, accomplishments and regrets. Characters are com-

plex to design because they are similar to living sentient beings,

even though, they are designed to fulfill a role in a specific context.

At this stage, the characters personality is constructed and will

define the characters appearance. It is extremely important to point

out that, from this stage onwards, the constraints will vary accord-

ingly with the context and they will have a major role on each stage.

Characters are the personification of ideas which usually carry

out a message. These ideas manifests through a series of aspects

such as the character way of talking or how the character dresses

and how it behaves under certain circumstances. Tillman [17] refer

to these specific traits as archetypes. Archetypes are characteristics

which people can easily relate to and understand. Tillman presents

six types of archetypes: hero, shadow, fool, animus/anima, men-

tor, trickster. They represent fragments of human personality traits.

Using archetypes is highly recommended to construct the base of a

character design. However, a character might be more complex and

composed by more than only one archetype.

It is important to add human feelings and emotions to a character

in order to improve the credibility on the design. When developing

the psychological aspects of a character, the artist has to focus on

what is the role of that character in the product and within the sto-

ryline. At this point the artist have reached a connection between

the story, the media and the audience. The character must fulfill its

role in the story at the same that time it must appeal to the audience,

and it must be suitable for the media it is inserted on.

The element Story influences the character in two different ways.

One is through the story of the character itself, and the other one is

through the story of the world. A narrative involves the construc-

tion of a world or scenario where characters are inserted and inter-

act among themselves. These interactions are what build a character

personality, while the world defines the physical aspects of the char-

acter. Personality affects how the character behaves, its posture, its

relationships, its goals, its motivations etc. The world defines why

the character wears a given type of clothes, its body type, the phys-

ical qualities of the character in general.

The element audience, on the other hand, defines what art style

and tone the character should be. When an artist is working on a

project, whether it is a personal project, he or she will be creating a

product for a certain public. When an artist works for a company,

other professionals will be dealing with what the audience wants.

It is through an analysis of the audience that the tone of the story

is adjusted, and because of that, the tone of the character itself will

change.

The construction of a character’ psyche must also obey to the

rules of the media it will be published on. While in movies artists

SBC – Proceedings of SBGames 2016 | ISSN: 2179-2259

Art & Design Track – Full Papers

XV SBGames – São Paulo – SP – Brazil, September 8th - 10th, 2016

551

create full characters that can inspire people, characters that people

can relate to their ideas or story, in games we have three differ-

ent types that must help the gameplay and story [7]. Avatar is a

character usually presented in first-person that displays little to no

depth in order to not disrupt the idea that the player must assume

the role of filling the characters role. Actor is the denomination for

third person view characters, which presents enough information

to stand out as a character without disturbing the player. Finally,

Non-Playable Characters, require full character design if they have

an important role in the story.

Designing a characters mind is a difficult task in which it is nec-

essary to fulfill various requirements. Consequently, character de-

signers need to understand many subjects and research a lot before

coming up with a visual for the character. Also, it is important to

have in mind that this stage consumes time, nonetheless the artist

must manage well the time thats being spent in which stage.

3.2.4 Imagetic Research - Visual References

Artists usually tend to think in a graphical fashion. While having

ideas for the characters personality, artists usually visualize how

the characters would look like, what type of materials should be

used, how would be the silhouette of the character, among other

things. However, remembering every texture and pattern is really

hard. Left alone human and animal anatomies [17]. Artists actually

work within a time frame, so if they were to learn how to design-

ing certain material or muscle or if they were to design a material

without knowing it, artists would take more time than they should.

It would cost the company and the artist money. In order to reduce

time and conclude a work with good quality, artist use images for

reference.

Imagetic references are images that contain patterns, shapes, sil-

houettes, materials, constructs, pieces, anatomy references, and any

other type of graphic recording of a element that can be used for in-

spiration. Using imagetic references serve not only for reproducing

materials but they also stimulate the creativity of the artist. Some

people end up being used by the reference instead of using the ref-

erence. Also, some people believe that using reference is cheating

[17]. Both cases happens because people do not understand when

and how using a reference is welcome. References are a tool to help

the artist and they are never to be used as a guideline for the final

design. If the former happens, the artist will be just creating a copy

of an image.

On the other hand, a character possesses an anatomy that may

vary according to the species it belongs to. Moreover, a character

usually wears clothes and accessories, it might have scars, tattoos or

other marks over its body. Using references help the artist to design

the character faster. There are different ways to use references in a

character design or concept art, so most of those are for materials,

lighting and composition. Also, it is a valid method to use parts

of the reference images on the design to compose different parts of

it. The major problem to solve in this case regards time. In short,

as long as the final design is not a copy of an image, there is no

problem utilizing references freely.

3.2.5 Sketching the Character

The Sketching stage is what summarize the concept art. For a

reader, it is not a hard task to visualize and draw a character of

the book using only his or her imagination. Be as it may, draw-

ing a character is fairly easy. The tricky part lies on how good the

character was drew. The good aspect is actually how coherent and

consistent that design is. Even a professional character designer

needs to draw many sketches until she haves a few drawings good

enough to polish them and turn them into a final design.

Sketches consist of quick drawings commonly used to practice.

It is through sketches that artists can improve ability to transmit

ideas more clearly [11] [15]. Sketches help the artist to improve

their creative skills and to come closer of a solution. The many

drawings produced are tests in order to see how an idea turns out

when represented graphically. From analysing the sketches, artists

and creative directors can understand what works and what does

not.

Although sketches are similar to drafts, when applied onto the

context of the industry, sketches show a certain level of finishing. It

is important to have a clear design, where all elements are showing

up. Sketches save time and don not affect negatively the production

line. Hundreds of sketches are made during the development of a

typical game or movie in the industry, and each sketch represents an

idea that might or might not work in the game. That is the important

part of this stage: sketches allow the character designer to add ideas

and elements without worrying about constraints. Artist clearly still

do have restrictions on what she should put on, however the way the

artist decides to convey that ideas in sketches is totally up to her.

Character Design, as well Concept Art, is based on the produc-

tion of ideas. Therefore, learning how to sketch fast and detailed

enough is a skill necessary for a professional on the area. Sketches

must translate the principal characteristics established from the

story into a simple 2D drawing, composed by lines and simple shad-

ing. Most elements must be flat and the line work must show the

principal characteristics, such as main equipment, marks, clothing

etc. Also, the overall silhouette must pass the idea of who is the

character. Finding a strong and remarkable overall design is the ob-

jective of this stage. The drawings should be rough and yet clear

enough to be understood. Colors are not necessarily used in this

stage, although their use are not prohibited. Another helpful insight

for designing a character consists on writing, above the character,

its main characteristics that are being explored on the design.

3.2.6 Rendering the Character

At the end of the Sketch stage, the best sketches are selected to be

further polished in the Rendering stage. Render, as used in this pa-

per, refers to the action of depicting or representing an idea graphi-

cally. It is expected a good-quality depiction from the artist, there-

fore in this stage designers start to add details and color to the best

sketches.

Rendering stage is commonly confused with Illustration. Taka-

hashi e Andreo [15] argue that the essence of illustration is com-

municating a thought: illustrations are rendered images focused on

transmitting a message. Commonly, illustrations depict more than

only the character itself, because some background landscape and

stylized lighting is also displayed in a typical case. Promotional Art

is also usually confused with Concept Art. However, Promotional

Art are images created with the sole purpose of selling a product.

This type of art sometimes is made by polishing an illustration to a

real concept art image.

Not all images created on the rendering stage have proper tex-

turing and outstanding visuals. Concept Art is a process within the

industry. Artists do not have the luxury to finish every single im-

age because through the concept art they already passed the idea

in terms of their designs. Time is one of the critical constraints on

this stage. Due to this, images have to be produced quickly so the

other professionals can do their jobs and finish the product within

the schedule.

Character Designers’ works often will be applied to a product

that will not directly require the produced images. These images

are just a reference for other professionals use them to create the el-

ements present in the final version. For example, 3D Modelers need

the characters concepts in order to handcraft enthralling meshes for

the game. Consequently, modelers will need a design which can tell

them how is the character appearance overall, what equipment and

clothes the character wears, what are the materials of each prop,

among other technical aspects.

Rendering a character takes in consideration different techniques

SBC – Proceedings of SBGames 2016 | ISSN: 2179-2259

Art & Design Track – Full Papers

XV SBGames – São Paulo – SP – Brazil, September 8th - 10th, 2016

552

and the use of various elements such as color and lighting. The de-

signs must present a composition that shows balance and harmony.

Adding too much details will pollute the design and its probably go-

ing to confuse the audience, making them dislike the character. It is

important to leave some breathable areas within the design, so the

main interesting areas will pop up. Another thing to worry about

while creating a character design is the negative spaces and how

they work to make the character silhouette interesting. During all

process, the designer shall revise the characters guidelines (story,

audience, aesthetics) so there will be no inconsistencies within the

design.

The use of colors and light defines the volume and materials

throughout the design. Colors come from reflected light, therefore

they act as a delimitation for the materials and volumes present in

nature. Effective coloring will bring to light technical aspects such

as the opacity and reflectiveness of the material, the weight of the

equipment, the textures of each element. Moreover, a shading also

provides a feeling of who the character is. The color used to com-

pose the character also influences on how the audience will perceive

the character and its role in the story [8] [7] [17].

The constant use of reference solves most of the problems a char-

acter designer might encounter along its work. It is not necessary

to use references only as guide and try to render the character by

hand. Technology allow us to use tools for picking the colors, se-

lecting areas of images and using them in the character design, cre-

ate textures to cover big areas, among other possibilities. Adopting

tools that speed up the construction of the design is fundamental

for meeting deadlines. Character Designers are professionals that

work for companies in order to obtain money in exchange for cre-

ating outstanding characters. The cohesiveness and consistency of

the characters created will depend on how the artist follow the steps

proposed herein and apply the techniques.

3.3 Practical Considerations

After going through the proposed Character Designer process, the

artist should have strong, coherent and consistent designs that obey

restrictions. Usually, the characters concepts will be revised by the

creative directors and eventually reworked before receiving a final

approval. The designs will them move forward to next team of

professionals to be converted in a format suitable for application

into the final product. The concept art is the basis for the other

areas and if the designs are not satisfying enough, this could affect

the entire line of production.

4 STUDY CASE

Evaluating the validity of a creative process is a difficult task. Due

to the lack of an extensive academic documentation, obtaining an

evaluation method for character design processes may pose as a

matter of opinion. The process proposed by Seegmiller’s [14]

adopts Evaluating Results as the final step, but the evaluation turns

out to be performed according with the satisfaction of the client that

may vary depending on many factors. It was proposed to apply the

method into a product, and to evaluate results according with the

product’s specifications. In order to showcase how flexible the pro-

posed process can be, we decided to apply it in the development of

a Trading Card Game which utilize Brazilian myths as cards.

TCGs combine the collectible aspect of cards as physical objects

and strategy games [5]. The Base Ball Game, published in 1904 by

The Allegheny Card Co., is considered to be the first TCG. How-

ever, the genre only achieved success in 1993 with Magic: The

Gathering

R

published by Wizards of the Coast. The initial re-

sponse to the game was unexpectedly good, and the company de-

cided to continue its production. This accomplishment marked a

change in the hobby market since many players started to buy TCGs

instead of the popular statuettes used in RPG boards.

4.1 Prototype TCG

The Legendary Trinity TCG was created in order to demonstrate

the process of Character Design can be used in different medias

and genres. The proposed games theme is inspired by Brazilian

mythology and it has a more realistic and serious approach for card

illustrations. Through research about Brazilian folklore, valuable

information was gathered about the fantastic beings and the legends

origins.

Brazilian folklore is rich in stories of fantastic beings that ruled

the jungle and the dark corners of cities. Unfortunately, most of

these stories were lost as time passed by, remaining only the for-

eigner version of these myths or the child version of them, as ob-

served in the TV show Stio do Pica Pau Amarelo. Although this

show is, to a certain degree, responsible for preserving Brazilian

legends, it ended up popularizing a version of the legends that are

far from their original meanings. This observation supports both

the importance and the challenge behind testing the process pro-

posed in this paper by creating a TCG whose universe is inhabited

by characters from Brazilian myths.

4.2 Applying the Character Design process

The process proposed by this article, observed in Figure 3, separates

the Character Design into Background and Foreground processes.

The entire process was evaluated by a solo artist working in this

production. This peculiar experimental setup provided for a broader

and deeper observation about how the work flows in contrast to

larger and more uncontrolled teams.

4.2.1 Background Processes

As discussed, Background processes offer the guidelines for the

final design. Therefore, we defined the conceptual and physical

constraints applicable in the context of the prototype TCG. These

are listed below:

• Infrastructure: Illustrations must be designed digitally, us-

ing adequate software to produce high quality images.

• Time: The established time was the due date of the submis-

sion of this paper.

• Audience: The audience was identified as teenagers and

adults, comprising people that are at least 16 years old.

• Story: In a dystopian dying Earth, different factions struggle

to survive while fighting among themselves. With the dis-

covery of a portal that connects this world to another one with

vast natural resources, these factions start a war to decide who

will rule the new world. In this war, battles are fought by sum-

moning creatures of immense power.

• Aesthetics: The TCG follows a realistic art style similar to

Magic: The Gathering

R

.

• Media: Print media, i.e., trading cards.

4.2.2 Foreground Processes

After having the Background processes defined, we start to work on

the Foreground Processes, which corresponds to the character de-

sign itself. It is valid to note that the process is meant to be efficient

and to save time. Therefore, the steps are performed quicker and

the explanation about them are also shorter:

• Identification and Analysis of the problem: The problem in

this case is closely related to the media adopted for releasing

the product into. Trading cards are small pieces and the char-

acters must appear in a visible, clearly understandable way in

these the cards. Also, it is needed to create a visual that can

appeal to the public in order to promote the Brazilian mythol-

ogy.

SBC – Proceedings of SBGames 2016 | ISSN: 2179-2259

Art & Design Track – Full Papers

XV SBGames – São Paulo – SP – Brazil, September 8th - 10th, 2016

553

• Conceptual Research: Brazilian mythology was vast, full of

creatures of great power that protected nature. Unfortunately,

this mythology was oral with almost no written records. Due

to time and insertion of different cultures, most of the fan-

tastic creatures had their story distorted, changed. Luiz da

Camara Cascudo was one of the pioneers in deciding to cat-

alogue Brazilian myths. In his pioneer work Geografia dos

Mitos Brasileiros (1947), the author describes several myths

in an attempt to preserve the origin of those stories. We cre-

ated our characters inspired by information found on his cata-

logue and in his detailed description of the characters in those

legends. This will make the characters look more serious and

convincing.

• Defining Character’ psychological aspects: Characters’

psychological traits as depicted on cards need to portray their

importance for the game. Cards have different abilities and

strategies that are connected to features from characters they

display. Therefore, in a TCG, the characters themselves are

important to express the function they represent. Moreover,

the collectible aspect that the card possess allows the illus-

tration to aggregate value into the final product while an art-

work collection. Therefore, the chosen legends were based on

their popularity and abilities portrayed in the actual mythol-

ogy. Various entities like Saci, Tup

˜

a, Iara, Werewolf and Cu-

rupira were considered within this step.

• Imagetic Research: Since myths are depicted as sentient

creatures on the TCG, our research was focused on animals

that possess similar features and behaviors to the ones de-

scribed on the myths’ stories.

• Sketching the Characters: Sketches were developed in or-

der to portray the personality and and physical traits of the

inspiring characters in a readable way. Additionally, we tried

to preserve the earliest known aspects of these myths. This

can be observed in Figure 4.

• Rendering the Characters: As observed, the sketches best

fitting to the project needs were chosen to be polished. This

allowed them to become suitable for insertion into the TCG

cards, as shown in Figures 5 and 6.

4.3 Results and Discussion

The process helped to achieve eligible results. As observed in Fig-

ure 5, the Saci is a combination of furtive animals, such as monkey

and the tapera naevia. For being an alien deity, concepts of Tup

˜

a

are depicted as an unnatural being (Figure 4). The Curupira is fa-

mous for tricking hunters, therefore the chameleon was a perfect

match to this furtive creature in Figure 6.

Figure 4: Sketches for Iara, Tup

˜

a and Werewolf before filtering.

Figure 5: Final render of the Saci, as a sarcastical thief: this explains

the many accessories detailing this render.

The proposed process proved itself well-defined in the sense that

it allowed for developing characters that are effectively coherent

and consistent for application in the game. In fact, despite sub-

jective interpretations, the process led to the core building blocks

necessary to give shape for characters that are solid from many per-

spectives. Moreover, by following these steps essentially allows the

artist to estimate how far they are from obtaining the desired result

when considering specific constraints: such perception is pivotal

for keeping the production on schedule.

Sad to say, in crude, real-world scenarios, some Foreground pro-

cesses may be minimized or even bypassed by artists depending on

the situation. Products with extremely prohibitive deadlines, for ex-

ample, prejudice the Defining Character’ psychological aspects and

Imagetic Research steps. On the other hand, freelancers may ignore

some Background processes, such as Infrastructue due to their free-

dom to choose tools at their own will.

Finally, it was observed that some complementary tools might fit

into the process in order to further assist artists to keep their focus.

This, however, is a matter for future research we discuss in the next

section.

5 CONCLUSION AND FUTURE WORK

This paper described new design process crafted specifically for ob-

taining characters that are both consistent and coherent. This pro-

cess combines the strengths of two processes proposed by [14] and

[17]. By adopting the steps suggested in this investigation, artists

are endowed with a work method that provides means for obtain-

ing conceptually solid characters fitting to the application context.

In fact, most modern productions require large teams formed by

different profiles working together focusing on the same result.

The proposed process was empirically assessed throughout the

development of characters for a prototype TCG. Altough there was

a sole artist working on that product, this evaluation allowed to pin-

point important insights presented in this paper regarding the pro-

cess’ effectiveness. The process contributed for developing of a

eligible product in a more objective and predictable fashion.

SBC – Proceedings of SBGames 2016 | ISSN: 2179-2259

Art & Design Track – Full Papers

XV SBGames – São Paulo – SP – Brazil, September 8th - 10th, 2016

554

Figure 6: Final render for the Curupira riding a warthog as a method

for keep its track hidden from hunters.

It is worth observing the process presented herein is very de-

tailed. At first, some professionals in haste may avoid perform-

ing all the suggested steps. However, productions aiming for high-

quality characters may benefit from guidance found on both Back-

ground and Foreground processes.

Assessing the process in terms of multiple artists working in

teams and different products are left for future work. Other inves-

tigation of interest concerns how to insert this process into a wider

production pipeline. Developing tools for assisting the artists and

other stakeholders also poses as a promising challenge for further

studies.

REFERENCES

[1] S. Bartlett. The mythology bible: The definitive guide to legendary

tales. Sterling Publishing Company, Inc., 2009.

[2] S. M. Bigal. M

´

ıdia, mito e midiac¸

˜

oes. Midi

´

aticos e Coexistentes,

2005.

[3] M. S. Contrera. Publicidade e mito. Significac¸

˜

ao: Revista de Cultura

Audiovisual, 29(18):59–87, 2002.

[4] S. Coros. Creating animated characters for the physical world. XRDS:

Crossroads, The ACM Magazine for Students, 22(3):32–37, 2016.

[5] B. David-Marshall, J. v. Dreunen, and M. Wang. Trading card game

industry-from the t to the c to the g. Retrieved December, 12:2013,

2010.

[6] P. Douglass. The influence of literature and myth in videogames. IGN.

Retrieved, 29, 2006.

[7] T. Gard. Building character. Game Developer Maganize, 2000.

[8] P. Hodges. The character design process. research, education and

design experiences, page 106, 2012.

[9] C.-J. Jin and K.-J. Kim. A study on traditional art expression in chi-

nese myth martial mmorpg character design. Journal of Korea Game

Society, 13(2):119–130, 2013.

[10] K. Kaplan, J. Grant, K. G

¨

uc¸l

¨

u, C¸ .

¨

Unal, and E. Yakupo

˘

glu. An exam-

ple for 3d animated character design process: The lost city antioch.

Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 122:65–71, 2014.

[11] G. A. Lippincott. The Fantasy Illustrator’s Technique Book: From

Creating Characters to Selling Your Work, Learn the Skills of the Pro-

fessional Fantasy Artist. Barron’s Educational Series, Incorporated,

2007.

[12] S. C. C. C. S. Martins. Publicidade e m

´

ıdia: A presenc¸a de mitos

na publicidade e padr

˜

oes na construc¸

˜

ao da cultura de massa contem-

por

ˆ

anea. VII Jornada de Iniciao Cientfica, 2011.

[13] E. Montenyohl. Divergent paths: On the evolution of” folklore” and”

folkloristics”. Journal of Folklore Research, pages 232–235, 1996.

[14] D. Seegmiller. Digital Character Painting Using Photoshop CS3.

Graphics series. Charles River Media, 2008.

[15] P. K. Takahashi and M. C. Andreo. Desenvolvimento de concept art

para personagens. SBC-Proceedings of SBGames, 2011.

[16] F. Thomas, O. Johnston, and F. Thomas. The illusion of life: Disney

animation. Hyperion New York, 1995.

[17] B. Tillman. Creative Character Design. Taylor & Francis, 2012.

[18] C. Turri. IP:InformAnimation Hand Book. Francoangeli, 2011.

[19] Zupi. Concept art issue. Revista Zupi, 22(01):04, 2010.

SBC – Proceedings of SBGames 2016 | ISSN: 2179-2259

Art & Design Track – Full Papers

XV SBGames – São Paulo – SP – Brazil, September 8th - 10th, 2016

555