Cornell Hospitality Report • February 2017 • www.chr.cornell.edu • Vol. 17, No. 4 1

What Matters Most to

Your Guests:

An Exploratory Study of Online Reviews

A

n examination of over 95,000 reviews and ratings for 99 independent, high-end hotels

and resorts highlights the importance of the hotel industry’s core product, namely,

consistently excellent service supporting a comfortable, well-appointed room. Based

on reviews and ratings posted on TripAdvisor, Expedia, and Booking.com, the

analysis found that properties with the most consistent service also had the highest ratings, while

hotels with inconsistent scores also had relatively low ratings. Quantitative analysis revealed that

service and rooms were overwhelmingly the most important aspects of these high-end properties,

while facilities, location, and amenities moved the meter far less. A qualitative analysis of the

words used in the reviews again highlighted the essential nature of service and rooms, both for

high-rated and low-rated properties. Top-rated reviews included such words as friendly, helpful,

excellent, and beautiful, while words that appeared only in the low-rated reviews included didn’t,

bathroom, front, desk, and price, hinting at issues that resulted in those lower ratings. The ndings

can be applied by management of both high- and low-rated hotels to avoid distractions and to

focus on hotels’ fundamental purpose of providing excellent service and a good night’s sleep.

CENTER FOR HOSPITALITY RESEARCH

By Jie Zhang and Rohit Verma

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

An examination of over 95,000 reviews and ratings for 99 independent, high-end hotels and

resorts highlights the importance of the hotel industry’s core product, namely, consistently

excellent service supporting a comfortable, well-appointed room. Based on reviews and

ratings posted on TripAdvisor, Expedia, and Booking.com, the analysis found that properties

with the most consistent service also had the highest ratings, while hotels with inconsistent

scores also had relatively low ratings. Quantitative analysis revealed that service and rooms

were overwhelmingly the most important aspects of these high-end properties, while

facilities, location, and amenities moved the meter far less. A qualitative analysis of the

words used in the reviews again highlighted the essential nature of service and rooms, both

for high-rated and low-rated properties. Top-rated reviews included such words as friendly,

helpful, excellent, and beautiful, while words that appeared only in the low-rated reviews

included didn’t, bathroom, front, desk, and price, hinting at issues that resulted in those lower

ratings. The findings can be applied by management of both high- and low-rated hotels to

avoid distractions and to focus on hotels’ fundamental purpose of providing excellent service

and a good night’s sleep.

2 The Center for Hospitality Research • Cornell University

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

This report includes information from members of Preferred Hotels & Resorts, the world’s largest

independent hotel brand, representing more than 650 distinctive luxury hotels, resorts, and resi-

dences in 85 countries across the globe (https://preferredhotels.com). To help ensure the highest

levels of customer satisfaction, every property within the brand’s portfolio is required to maintain

the high quality standards and unparalleled service levels required by the Preferred Hotels &

Resorts Integrated Quality Assurance Program, a customized social media tool that takes hotel

quality assurance into the next generation, combining the traditional site inspection by a profes-

sional third-party expert with a customized social media element that provides real-time quality

assessment scores.

Rohit Verma, Ph.D., is the dean of external relations for the Cornell College of Business at Cornell University, the executive

director of the Cornell Institute for Healthy Futures (http://ihf.cornell.edu/), and the Singapore Tourism Board Distinguished

Professor in Asian Hospitality Management at the Cornell School of Hotel Administration (SHA).Prior to his appointment at Cornell

University, Verma was the George Eccles Professor of Management at the David Eccles School of

Business, University of Utah. He has taught undergraduate, MBA, and executive courses at several

universities around the world, including DePaul University, German Graduate School of Business and

Law, Helsinki School of Economics, Indian School of Business, Korea University, and the University of

Sydney. Verma has published over 70 articles in prestigious academic journals and has also written

numerous reports for the industry audience. He regularly presents his research, participates in invited

panel discussions, and delivers keynote addresses at major industry and academic conferences around

the world. He is co-author of the Operations and Supply Chain Management for the 21st Century

textbook, and co-editor of Cornell School of Hotel Administration on Hospitality: Cutting Edge Thinking and Practice, a professional

reference book that includes works of several of his colleagues at Cornell. Verma has received several research and teaching

awards including CHR’s Industry Relevance Award and SHA’s Masters Core Class Teaching Award; the Skinner Award For Early

Career Research Accomplishments from the Production and Operations Management Society; the Spirit of Inquiry Award, the

highest honor for scholarly activities within DePaul University; the Teaching Innovation Award from DePaul University; and the

Professional Service Award from DESB University of Utah. He received his Ph.D. and MS degrees from the University of Utah. He

received his Btech degree from the Indian Institute of Technology.

Jie J. Zhang, DBA, is an assistant professor of service operations management at the Gustavson School of Business, University

of Victoria. Jie is primarily interested in improving the performance of service organizations while contributing to a sustainable

future. Jie’s research has investigated topics such as environmental performance of service operations,

learning and service innovation, service triads, and professional service life cycle. Her work has been

published in journals such as the Journal of Operations Management, Service Science, Journal of

Service Management and Cornell Hospitality Quarterly. Through her empirical research efforts, Jie

strives to enhance the performance of service systems by contributing to knowledge on the value-

creation interactions (i.e., coproduction) between service organizations and their customers. Jie’s

teaching reects her interest in value co-creating service systems. Jie previously taught at the University

of Vermont in the U.S., and particularly enjoyed being part of the successful launch of the highly

innovative Sustainable Entrepreneurship MBA (SEMBA) program at UVM. Before joining academia, Jie worked as the Systems

Manager of the Division of Applied Mathematics, Brown University, for nine years.

Cornell Hospitality Report • February 2017 • www.chr.cornell.edu • Vol. 17, No. 4 3

CORNELL HOSPITALITY REPORT

What Matters Most to Your

Guests:

An Exploratory Study of Online Reviews

T

he hotel industry is one of many where guests rely on online reviews to make

purchase decisions.

1

Unlike many other businesses, however, a group of third-party

sites, the online travel agents (OTAs), host hotel reviews and ratings (not to mention

distribution). There’s no doubt that consumers’ reviews are important both to the

industry and its guests. Research has, for example, shown a robust positive link between online

reputation and increase in ADR, occupancy, and RevPAR.

2

Guest reviews also can provide a wealth

of information to hotel managers regarding what elements of a guest stay are most important,

provided one can analyze the guests’ comments. Given that the reviews carry the voice of the

customers in the form of unsolicited feedback on hotel operations,

3

we investigate which aspects

of the perceived guest experience have the greatest eect on guests’ assessment of their hotel stay,

by considering both numerical rating scores and words used in the reviews.

1

Beverley A. Sparks and Victoria Browning, “The Impact of Online Reviews on Hotel Booking Intentions and Perception of Trust,” Tourism

Management 32, no. 6 (2011): 1310–23.

2

Chris Anderson, “The Impact of Social Media on Lodging Performance,” Cornell Hospitality Report 12, no. 15 (2012): 6–11; and Chris K. An-

derson and Benjamin Lawrence, “The Inuence of Online Reputation and Product Heterogeneity on Service Firm Financial Performance,” Service

Science 6, no. 4 (2014): 217–28.

3

Hyun Jeong Han et al., “What Guests Really Think of Your Hotel: Text Analytics of Online Customer Reviews,” Cornell Hospitality Report 16,

no. 2 (2016): 3–17; and Stuart E. Levy, Wenjing Duan, and Soyoung Boo, “An Analysis of One-Star Online Reviews and Responses in the Washing-

ton, DC, Lodging Market,” Cornell Hospitality Quarterly 54, no. 1 (2013): 49–63.

By Jie Zhang and Rohit Verma

Beverley A. Sparks and Victoria Browning, “The Impact of Online Reviews on Hotel Booking Intentions and Perception of Trust,” Tourism

Management 32, no. 6 (2011): 1310–23.

Chris Anderson, “The Impact of Social Media on Lodging Performance,” Cornell Hospitality Report 12, no. 15 (2012): 6–11; and Chris K. An- derson

and Benjamin Lawrence, “The Influence of Online Reputation and Product Heterogeneity on Service Firm Financial Performance,” Service Science

6, no. 4 (2014): 217–28.

Hyun Jeong Han et al., “What Guests Really Think of Your Hotel: Text Analytics of Online Customer Reviews,” Cornell Hospitality Report 16, no. 2

(2016): 3–17; and Stuart E. Levy, Wenjing Duan, and Soyoung Boo, “An Analysis of One-Star Online Reviews and Responses in the Washing- ton,

DC, Lodging Market,” Cornell Hospitality Quarterly 54, no. 1 (2013): 49–63.

4 The Center for Hospitality Research • Cornell University

ers’ purchase decision process.

4

Moreover, consumers

have become increasingly adept at evaluating the veracity

of online reviews by triangulating multiple sources and

their own contextual knowledge.

5

Because it’s clear that

hotels can apply online reviews for performance improve-

ment and revenue enhancement, we investigate ways that

management can analyze the rich and dynamic online

review data for insights on aspects of the stay that contrib-

ute to high guest satisfaction and gaps that can be closed.

Although online hotel ratings have been found to be

largely credible,

6

it is worth noting sources of potential

biases in online data, particularly fraudulent reviews,

written by people who have not actually experienced the

service.

7

Another source of bias is self-selection. Even if a

review is genuine, the comments represent the views of

customers who have chosen the online platform to share

their opinions publicly. That group may be dierent in

some way from those who do not post reviews. We also

note that guests have a diverse interpretation of rating

scales,

8

which leads to heterogeneous information.

4

Bassig Migs, “2016 Trends in Hospitality and Travel,” January

18, 2016, http://www.reviewtrackers.com/2016-trends-hospitality-

travel/.

5

Russell S. Winer and Peter S. Fader, “Objective vs. Online

Ratings: Are Low Correlations Unexpected and Does It Matter? A

Commentary on de Langhe, Fernbach, and Lichtenstein,” Journal of

Consumer Research 42, no. 6 (2016): 846–49.

6

Peter O’Connor, “User-Generated Content and Travel: A Case

Study on Tripadvisor. Com,” Information and Communication Technolo-

gies in Tourism 2008, 2008, 47–58; and Julian K. Ayeh, Norman Au, and

Rob Law, “‘Do We Believe in TripAdvisor?’ Examining Credibility Per-

ceptions and Online Travelers’ Attitude toward Using User-Generated

Content,” Journal of Travel Research, 2013, 47287512475217.

7

Eric T. Anderson and Duncan I. Simester, “Reviews without a

Purchase: Low Ratings, Loyal Customers, and Deception,” Journal of

Marketing Research 51, no. 3 (2014): 249–69.

8

Russell S. Winer and Peter S. Fader, “Objective vs. Online

Ratings: Are Low Correlations Unexpected and Does It Matter? A

Commentary on de Langhe, Fernbach, and Lichtenstein,” Journal of

Consumer Research 42, no. 6 (2016): 846–49.

For this analysis, we were assisted by Preferred Ho-

tels & Resorts to collect 95,500 online ratings and reviews

of 99 of its independent hotels posted over a twelve-

month period on three top OTAs—TripAdvisor, Expedia,

and Booking.com. Although the hotels are independent,

they agree to follow the same quality standards as part

of their membership association. By focusing on inde-

pendent operating units in a well-dened segment with

similar quality standards, we control to some extent the

variations in guest preferences and demand, although the

hotels and resorts range in size from under 100 rooms to

well over 250 keys. The properties’ similarities allow us

to focus on the eects of specic operational drivers on

guests’ perceptions of their experience. In this study, we

are primarily interested in nding the answers to three

questions:

What are the drivers that matter the most in terms of

guests’ evaluation of their experience?;

How do these drivers relate to consumer review

scores at the property level?; and

What are the identiable consumer issues found in

the review text?

Although online reviews are widely viewed as reli-

able, we rst examine studies on the reliability of the

online reviews and ratings in assessing performance.

Then, our quantitative analysis uses regression to assess

the eects of key operational drivers on consumer review

ratings, while our qualitative study uses text analytics to

uncover common consumer concerns and to infer what

aspects of the guests’ stay have the greatest eect on rat-

ings.

Online Reviews as a Valuable Source of

Feedback

Online reviews continue to rise in importance, having

become second only to pricing as an element in consum-

E

xhibit

1

Hotel properties: geographic distribution and size

Continent Small

(<100 rooms)

Medium

(101-250 rooms)

Large

(>250 rooms)

Total

Europe 13 18 12 43

North America 3 13 22 38

Asia — 4 12 16

Africa — — 1 1

South America — 1 — 1

Grand Total 16 36 47 99

Bassig Migs, “2016 Trends in Hospitality and Travel,” January 18, 2016,

http://www.reviewtrackers.com/2016-trends-hospitality- travel/.

Russell S. Winer and Peter S. Fader, “Objective vs. Online Ratings: Are Low

Correlations Unexpected and Does It Matter? A Commentary on de Langhe, Fernbach,

and Lichtenstein,” Journal of Consumer Research 42, no. 6 (2016): 846–49.

Peter O’Connor, “User-Generated Content and Travel: A Case Study on

Tripadvisor. Com,” Information and Communication Technolo- gies in

Tourism 2008, 2008, 47–58; and Julian K. Ayeh, Norman Au, and Rob

Law, “‘Do We Believe in TripAdvisor?’ Examining Credibility Per-

ceptions and Online Travelers’ Attitude toward Using User-Generated

Content,” Journal of Travel Research, 2013, 47287512475217.

Eric T. Anderson and Duncan I. Simester, “Reviews without a Purchase: Low Ratings,

Loyal Customers, and Deception,” Journal of Marketing Research 51, no. 3 (2014):

249–69.

Russell S. Winer and Peter S. Fader, “Objective vs. Online Ratings:

Are Low Correlations Unexpected and Does It Matter? A

Commentary on de Langhe, Fernbach, and Lichtenstein,” Journal of

Consumer Research 42, no. 6 (2016): 846–49.

Cornell Hospitality Report • February 2017 • www.chr.cornell.edu • Vol. 17, No. 4 5

Design of the Study

We selected the 99 properties from Preferred Hotels

& Resorts’ international portfolio on the basis that the se-

lected hotels received a steady stream of daily reviews on

one of the three OTAs (Booking, Expedia, or TripAdvisor)

between May 1, 2015, and April 30, 2016. For this study,

we focused only on reviews written in English, leaving a

nal sample of 95,500 reviews. This language restriction

slightly reduced the number of reviews per property, yet

even the hotel with the fewest reviews averaged about 1.3

English reviews per day minimum. We therefore are rea-

sonably condent that these properties have established a

solid online reputation.

Exhibit 1 shows the geographic distribution of the

properties in the study, grouped by property size. The

majority of the hotel properties in the study are located in

Europe and North America, and nearly half of the hotels

and resorts have more than 250 rooms. This is consistent

with the hotel group’s focus on luxury properties.

Exhibit 2 shows the frequency distribution of total

daily English reviews from the three OTA sites. The mode

is around two such reviews per day, while a small number

of properties received more than six reviews per day.

The practical outcome of having such a strong stream of

reviews is that we can continuously collect near real-time

information on customer service experiences, which is not

possible with post-stay surveys and mystery shoppers, for

instance.

What Matters Most to Guests

To identify the drivers that matter the most in terms

of guests’ evaluation of their experience, we adopt the fol-

lowing process. We started with a detailed list of opera-

tional drivers typically included in the post-stay question-

naires solicited by the hoteliers, and compared that set

to those included in the consumer site review feedback

forms. We kept items in the intersection of those two sets

that are most frequently commented by reviewers. As

illustrated in Exhibit 3, the area where all three circles

overlap represents the drivers that matter the most to the

customers, given the available data.

Typical after-stay questionnaires are highly structured

and detailed about the guest’s experience in the hotel.

Populating the left-hand circle in Exhibit 3, our initial list

of drivers rated include front desk, ease of check-in, con-

cierge bell desk (check-in), location and building, room,

food and beverage, housekeeping, room service, service,

E

xhibit

2

Frequency distribution of the hotel properties (reviews per day)

Typical after-stay questionnaires are highly structured and detailed about

the guest’s experience in the hotel. Populating the left-hand circle in

Exhibit 3, our initial list of drivers rated include front desk, ease of

check-in, con- cierge bell desk (check-in), location and building, room,

food and beverage, housekeeping, room service, service, amenities and

facilities, ease of check-out, and concierge bell desk (check-out).

6 The Center for Hospitality Research • Cornell University

amenities and facilities, ease of check-out, and concierge

bell desk (check-out).

The OTAs encourage reviews by providing incentives

and streamlined feedback forms. As an example, Exhibit

4 shows the review submission interface on TripAdvi-

sor. Customers evaluate their experience by providing an

overall rating score, writing an open-ended review, and

giving subcategory ratings for service, location, and sleep

quality. Booking and Expedia provide similar mechanisms

that dier slightly in the choice and wording of the specic

areas to be rated.

Compiling the review categories from the three OTAs,

we listed twelve review categories, four of which were

rated most commonly: namely, service, room, location and

building, and amenities and facilities. As shown in Exhibit

5, the number of responses to the twelve categories varies

substantially, and half of the reviews gave no rating to any

of the twelve subcategories. For instance, we observe that

half of the reviews included a rating for service (47,337 out

of the 95,500 reviews, or 49.5 percent), while just under 6

percent of the consumers gave a separate rating for check-

in or checkout. Although both the review form design and

the consumers’ decisions during the submission of the

review could have contributed to the dierence in number

of ratings, it is clear that the top four rated areas identied

above account for the most memorable experience for most

guests.

E

xhibit

3

Drivers that matter most to guests

E

xhibit

4

TripAdvisor “write a review” interface

Driversincluded

inpost-stay

surveybyhoteliers

Driversincluded

inconsumersite

feedbackform

Driversrated

bymost

reviewers

Note: This exhibit shows the relevant sections of the TripAdvisor page. The full

page includes additional data for customer reviews.

Cornell Hospitality Report • February 2017 • www.chr.cornell.edu • Vol. 17, No. 4 7

Impact of the Drivers on Overall Rating

Each review has two overall ratings: Quantitative-

Score, which measures the overall experience at a hotel

property; and SentimentScore, which measures the overall

sentiment of a review based on a proprietary algorithm.

9

Out of the 95,500 reviews, we removed 808 reviews that

contained words that were outside the scope of the senti-

ment engine’s analysis.

Given the signicant variation in the number of

responses across the subcategories listed in Exhibit 5, we

explored whether the overall evaluations dier between

those from reviewers who chose to provide subcategory

ratings and those by customers who skipped the sub-

category ratings. Reviewers who provided subcategory

ratings appeared to be more critical in their overall

evaluations. In that regard, on average, the customers

who gave a rating to the service subcategory marked their

9

When a review is sent for sentiment analysis, the Sentiment

Engine breaks the entire review into sentences and then examines

each word of the sentence. As it comes across a positive and nega-

tive keyword, its assigns the corresponding score based on their

polarity, that is, positive (1) or negative (-1) to those keywords. The

sentiment engine also uses the modiers to assign weight or points to

the keyword. Thus, Very Good would be 2 points, and Good, 1 point.

Neutral keywords like “is,” “and,” and “the” are given a zero-degree

sentiment. Once the entire review has been analyzed (all sentences),

the Sentiment Engine takes the average of all the degree sentiments

and assigns the review an overall Sentiment score. The sentiment

engine presently processes eight languages. Reviews containing words

in languages out of the scope of the engine do not get analyzed and get

assigned a score of 0.

overall quantitative score slightly lower (8.61 out of 10)

than those who skipped the rating on service (quantita-

tive score averaging 8.69). An even larger gap exists for

the sentiment score. The mean of sentiment score is 7.11

for customers who rated service, as compared to 7.55 for

those who didn’t. This observation led us to focus on the

set of reviews that have both the individual subcategory

ratings (that is, service, room, location and building, and

amenities and facilities) and the overall rating, because we

wanted to assess how the ratings in these specic opera-

tional areas relate to the satisfaction level expressed by the

consumers. As mentioned earlier, we recognize that the

reviews and ratings were made by customers who chose

to provide evaluations based on their memory of past

lodging experience. These subcategories may have served

as cues that helped these customers remember more about

their stay and oer clues to the drivers of the overall

evaluations.

10

Consequently, the quantitative analysis described

below focuses primarily on the eects of the hotel subcat-

egory ratings on the overall ratings as measured by the

quantitative score and sentiment score. Given that there

are multiple reviews for each property during the study

period, we distinguish between two levels of analysis: the

individual reviews themselves and the hotel property that

the reviews describe. With these nested data, we use the

10

Keller, Kevin Lane. “Memory factors in advertising: The eect

of advertising retrieval cues on brand evaluations.” Journal of Consumer

Research 14.3 (1987): 316-333.

E

xhibit

5

Number of consumer responses on specic operational areas (total of 95,500 reviews)

Note: 50 percent of the reviews gave no rating to any of the twelve subcategories.

When a review is sent for sentiment analysis, the Sentiment Engine

breaks the entire review into sentences and then examines each word of

the sentence. As it comes across a positive and nega- tive keyword, its

assigns the corresponding score based on their polarity, that is, positive

(1) or negative (-1) to those keywords. The sentiment engine also uses

the modifiers to assign weight or points to the keyword. Thus, Very Good

would be 2 points, and Good, 1 point. Neutral keywords like “is,” “and,”

and “the” are given a zero-degree sentiment. Once the entire review has

been analyzed (all sentences), the Sentiment Engine takes the average

of all the degree sentiments and assigns the review an overall Sentiment

score. The sentiment engine presently processes eight languages.

Reviews containing words in languages out of the scope of the engine

do not get analyzed and get assigned a score of 0.

Keller, Kevin Lane. “Memory factors in advertising: The

effect of advertising retrieval cues on brand evaluations.”

Journal of Consumer Research 14.3 (1987): 316-333.

8 The Center for Hospitality Research • Cornell University

following two-level hierarchical regression model for the

overall rating score of the jth review on the ith hotel:

Overall Rating

ij

=β

0

+β

1

Service

ij

+β

2

Room

ij

+β

3

AmenitiesFacilities

ij

+β

4

LocationBuilding

ij

+β

(5-6)

HotelSizeDummy

ij

+u

i0

+ε

ij

Exhibit 6 shows the eect sizes estimated by the hier-

archical regression model. Column 1 shows the results for

dependent variable QuantitativeScore. The model’s likeli-

hood test against a linear model is 455.77 with a p-value

< 0.0001, providing evidence of cross-hotel variation.

Column 2 shows the results for SentimentScore as the

dependent variable. This model’s likelihood test against a

linear model is 132.27, again with a p-value < 0.0001, also

providing evidence of cross-hotel variation. We note that

the eect sizes reported in column 1 and column 2 are

comparable, which suggests similar driving forces behind

the ratings of the overall experience and sentiment.

QuantitativeScore. In the case of QuantitativeScore

of online reviews, what matters most is room, followed

closely by the rating on service (column 1). For every

point increase in these areas, there is an increase in

QuantitativeScore of 0.28 point (for the room) and 0.25

point (for service). In contrast, location and building have

the least impact on QuantitativeScore. This is not surpris-

ing given that the customers generally are clear about a

property’s location and facilities when they book a hotel.

Later, our qualitative analysis highlights another facet of

this relationship, namely, that service is more important

than the facilities.

We also observe systematic variation between large

and small hotels in QuantitativeScore. Small hotels

received better ratings than large hotels. Compared with

the hotels with 250 rooms or more, which is the reference

group, hotels with fewer than 100 rooms on average were

rated 0.411 point higher, while medium size hotels were

rated .260 point higher than large hotels in Quantitative-

Score.

SentimentScore. Room and service also contribute

heavily to SentimentScore, with service having only a

slightly greater eect than room rating (column 2). For

every one-point increase in either of these two areas, there

is roughly a 0.24-point increase in SentimentScore. On

average, guests who stayed in hotels with fewer than 100

rooms reported sentiment scores not signicantly dier-

ent from those staying in hotels with more than 250 rooms,

the reference group, while medium size hotels on average

scored 0.131 point higher in SentimentScore.

Consumer Preferences as Seen in the Review

Text

Our qualitative analysis explores reviewers’ attitudes

regarding the resorts’ attributes, based on comments

found in the reviews. We tally the words used in the

reviews and compare the result with overall quantitative

scores to determine which attributes are associated with

stable and positive reviews, and which aspects are more

commonly mentioned in poor reviews. Examination of

the subcategory ratings allows us to explore the factors

that contribute to high customer satisfaction in specic

areas, and to highlight areas that need particular attention.

For example, we can compare the frequently mentioned

features in hotels with high service ratings against those

with low ratings.

E

xhibit

6

The effect sizes of the subcategory ratings on the overall rating using two-level hierarchical regression

Independent Variables (1)

QuantitativeScore

(2)

SentimentScore

Room 0.281*** 0.234***

Service 0.253*** 0.244***

Amenities&Facilities 0.113*** 0.121***

Location&Building 0.054*** 0.087***

Properties with < 100 rooms 0.411** 0.128

Properties with 100-250 rooms 0.260* 0.131*

Intercept 3.803** 2.418***

Mixed-effects ML regression model statistics Wald chi2(6) = 2449.18

Prob > chi2 = 0.0000

Wald chi2(6) = 4219.37

Prob > chi2 = 0.0000

Note: * p-value<0.05, ** p-value <0.01, *** p-value <0.001; uctuated greatly, ranging from 6.52 to 8.5 during the 12-month period.

Consequently, the quantitative analysis described below focuses primarily on the effects

of the hotel subcat- egory ratings on the overall ratings as measured by the quantitative

score and sentiment score. Given that there are multiple reviews for each property

during the study period, we distinguish between two levels of analysis: the individual

reviews themselves and the hotel property that the reviews describe. With these nested

data, we use the following two-level hierarchical regression model for the overall rating

score of the jth review on the ith hotel:

Cornell Hospitality Report • February 2017 • www.chr.cornell.edu • Vol. 17, No. 4 9

Consumer Attitudes Found in Stable and

Unstable Reviews

To gauge a hotel’s service consistency, we consider

the variation in review scores during the study period.

Consistent reviews may be favorable for a hotel, but

only if those reviews contain high scores. When a hotel’s

reviews are relatively consistent, we can infer stable

underlying service delivery processes, whether strong

or weak. In this study, the consistent hotels generally

recorded higher overall scores. Consumer issues emerging

from low-scoring reviews or frequent complaints suggest

management priorities for process changes. Inconsistent

reviews tend to be related to poor overall ratings in our

study, and we consequently suggest that highly variable

reviews, where hotels seem to suer from unstable and

unpredictable service delivery processes, require urgent

management attention.

11

We use coecient of variation

(CV) of the overall quantitative score to measure the

consistency of the reviews a hotel accumulated over the

study period. The coecient of variation is the ratio of the

11

Variation reduction is a critical step towards understanding the

processes, stabilizing them, and detecting deviation from the standard

operating procedures.

standard deviation to the mean, which is a unit-less mea-

sure that allows a meaningful comparison of the level of

variability in the overall quantitative scores across hotels.

We calculate the CV for each hotel over the twelve-

month period using this equation:

CV

j

=

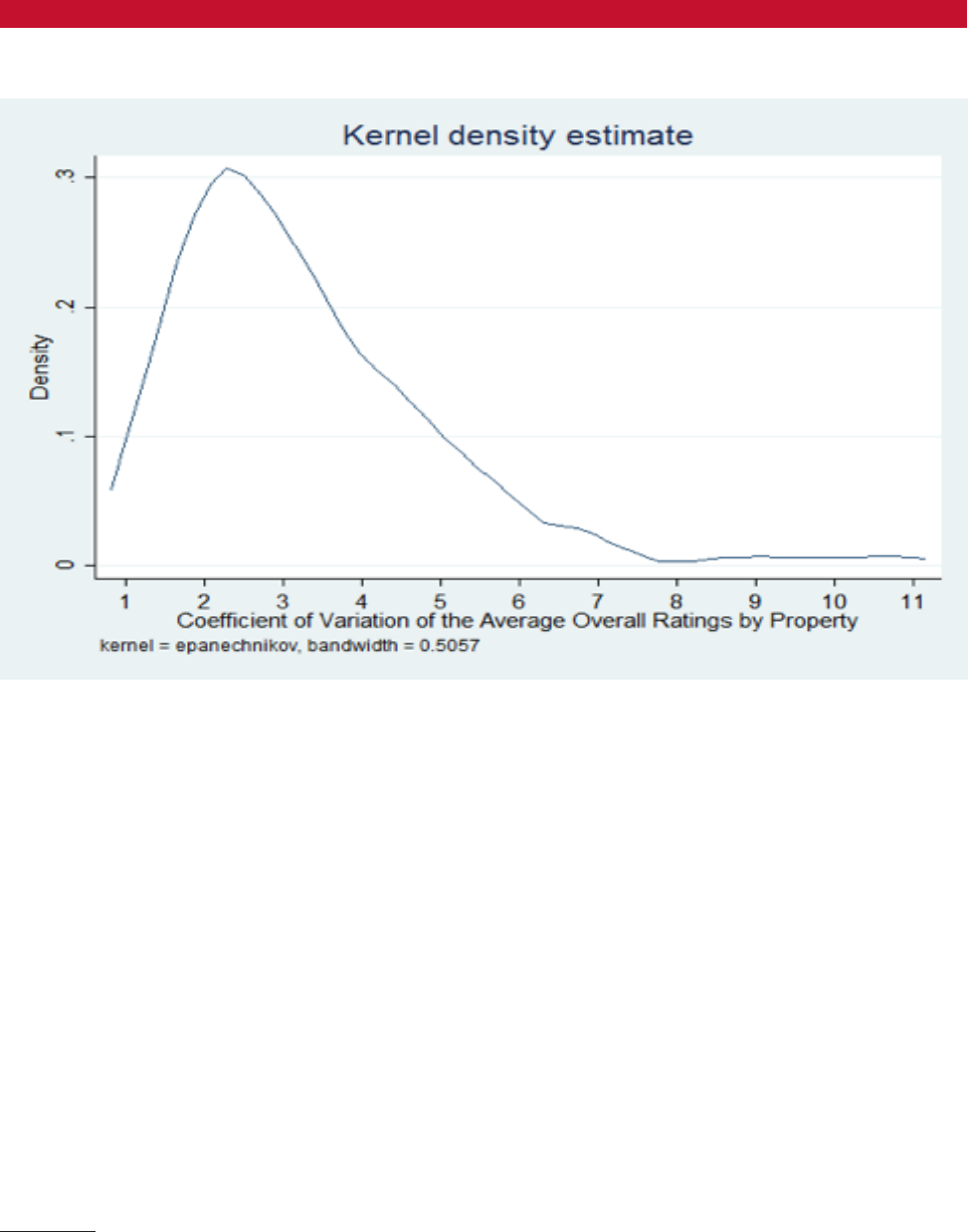

Exhibit 7 shows the CV frequency distribution for the

overall quantitative score for the 99 hotel properties in

the sample. We observe in Exhibit 7 that about 60 percent

of the properties achieved a low variability (CV < 3.3),

indicating relatively consistent overall quantitative scores

over the twelve-month period. It is worth noting that the

mean overall quantitative score for nine of the ten hotels

with the lowest CVs was 9.0 or better. On the other end of

the spectrum, the average monthly quantitative scores of

the 14 hotels with CV above 5 uctuate greatly, ranging

from 6.52 to 8.5 during the same period.

Exhibit 8 contrasts the average overall quantitative

scores of the ten hotels having the highest CV with those

of the ten hotels with the lowest CV. It is clear from Exhib-

E

xhibit

7

Variability in the overall quantitative scores at the hotel level over 12 months

100 × stdev(monthly average of the quantitative scores for hotel j)

average(monthly average of the quantitative scores for hotel j)

Variation reduction is a critical step towards understanding

the processes, stabilizing them, and detecting deviation from

the standard operating procedures.

10 The Center for Hospitality Research • Cornell University

it 8 that hotels in the high CV group were rated consistent-

ly lower than those in the low CV group. It appears that

the low score reviews are osetting the positive reviews,

thus detracting from the property’s online reputation.

12

A

high CV also suggests high variation in the execution of

the service processes, with the likelihood that the high CV

group suers from poor (or at best inconsistent) service

delivery and weak conguration of the service features.

The low CV group, on the other hand, can benet from

the consumer commentaries regarding how to further

optimize their service design.

We see the low CV group as serving as a center of

excellence where we can potentially identify consumer

preferences for better service conguration. Given that

it is cumbersome to list all the words mentioned in the

reviews, we list selected top words mentioned in reviews

that received a high overall score (greater than 9 on a scale

of 10) for the ten hotels in the low CV group (see Exhibit

9).

The text analysis rst conrms that service and room

are the subcategories that receive the most reviewer atten-

tion. It is important to note that these reviewers are highly

satised customers who shared their stories by elaborat-

ing on the personal experience, memories, and emotions

associated with their stay.

13

The text analysis results

complement the quantitative analysis by highlighting the

12

Frederick F. Reichheld, “The One Number You Need to Grow,”

Harvard Business Review 81, no. 12 (2003): 46–55.

13

As suggested in: B. Joseph Pine and James H. Gilmore, “Wel-

come to the Experience Economy,” Harvard Business Review 76, no. 6

(1998): 97–105; and Sriram Dasu and Richard B. Chase, “Designing the

importance of operational areas that were infrequently

scored by the customers but played a signicant role in

inuencing overall satisfaction, including food and bever-

age and recreational facilities.

Comparing Consumer Preferences Based on

Service Ratings

Because the quantitative analysis suggests that ser-

vice is the top driver of a hotel’s overall quantitative score,

we examined the top words in reviews for hotels that

scored high for service (4,579 hotels that scored between 9

and 10, about 10 percent of reviews) and the 5,337 (or just

over 11 percent) that scored poorly (4 or below). Exhibit

10 lists the top 33 words for each group, based on the

number of occurrences in the reviews.

We rst observe a strong overlap in the words that

appear in both favorable and unfavorable reviews, as the

two lists have 23 words in common. We can condently

conclude that these descriptors are universally important

for hotel guests. They include sta, comfortable, bed,

clean, room, good breakfast, memorable restaurant experi-

ence, and recreational facilities, such as the pool. Many of

these words also appear in the reviews of the consistently

high-rated hotels, as shown in Exhibit 9.

On the other hand, words that appeared in the posi-

tive reviews but didn’t get mentioned in the poor reviews

include friendly, helpful, excellent, beautiful, perfect,

recommend, lovely, wonderful, amazing, and denitely.

Soft Side of Customer Service,” MIT Sloan Management Review 52, no. 1

(2010): 33.

E

xhibit

8

Average overall ratings by hotels: high CV group vs. low CV group

Exhibit 8 contrasts the average overall quantitative scores of the ten

hotels having the highest CV with those of the ten hotels with the lowest

CV. It is clear from Exhibit 8 that hotels in the high CV group were rated

consistently lower than those in the low CV group. It appears that the low

score reviews are offsetting the positive reviews, thus detracting from the

property’s online reputation. A high CV also suggests high variation in

the execution of the service processes, with the likelihood that the high

CV group suffers from poor (or at best inconsistent) service delivery and

weak configuration of the service features. The low CV group, on the

other hand, can benefit from the consumer commentaries regarding how

to further optimize their service design.

Frederick F. Reichheld, “The One Number You Need to Grow,” Harvard

Business Review 81, no. 12 (2003): 46–55.

As suggested in: B. Joseph Pine and James H. Gilmore, “Welcome to

the Experience Economy,” Harvard Business Review 76, no. 6 (1998):

97–105; and Sriram Dasu and Richard B. Chase, “Designing the

Cornell Hospitality Report • February 2017 • www.chr.cornell.edu • Vol. 17, No. 4 11

E

xhibit

9

Words most frequently mentioned in high score reviews for properties with low variability in rating (number

of reviews = 8,562)

Word Total Occurrence Number of Reviews that Contain the Word*

hotel 8768 4246

staff 4406 3522

great 4348 2720

room 4055 2554

location 2870 2427

stay 3094 2265

exceptional 2279 2240

service 2162 1615

friendly 1710 1542

rooms 1708 1458

excellent 1854 1441

helpful 1488 1386

breakfast 1593 1353

wonderful 1519 1305

good 1676 1251

comfortable 1233 1113

nice 1438 1111

stayed 1251 1111

beautiful 1170 999

view 1223 978

pool 1177 974

clean 1034 959

perfect 1075 917

amazing 1162 913

time 1128 907

food 1048 904

place 1029 870

restaurant 964 846

Note: * Words most frequently mentioned in reviews on low-variability high-rated properties (number of reviews = 8,562).

In that list of words, we see the importance of personal

interactions that engender emotional responses in creating

memorable customer experiences. Another sore point that

emerges in poor reviews is the bathroom.

Managerial Implications

Not surprisingly, the key drivers in customer satisfac-

tion remain service and room. These two factors dominate

other factors that often have diverted management at-

tention, related to location and building and to amenities

and facilities. This pattern holds for both the quantitative

score and sentiment score, after controlling for hotel size.

Hoteliers should therefore focus on the operational areas

that speak volumes about service and room, such as ap-

propriately friendly service throughout the property, as

well as the quality of beds and ensuring a good night’s

sleep for the guest. The traditional lodging service that

delivers a good night’s sleep in a clean, well-functioning

room, together with availability of an excellent breakfast,

remains central to customer satisfaction.

A second implication is that operational consistency

is extremely important in a hotel’s overall rating. Thus,

12 The Center for Hospitality Research • Cornell University

focusing on avoiding operational “kinks” can be more

important than looking for the occasional “wow” factor.

Hotels that received highly variable review scores during

the twelve-month period scored much lower in the overall

ratings. Needless to say, frequent complaints about a

specic area, such as bathroom or breakfast, point to the

issues that require immediate attention.

Third, the descriptors identied in the review text ex-

press the consumers’ desire for solid delivery of core hotel

service oerings combined with favorable experiences

consisting of personal and emotional interactions with the

sta and a sense of well-being. As potential guests peruse

the online reviews, descriptions related to these two as-

pects will have an impact on their booking decisions and

expectations.

In conclusion, we want to once again emphasize that

despite amenities creep, architectural fads, and numerous

brand permutations, the core of the hotel business re-

mains creating a positive and memorable stay by focusing

on the fundamentals of hotel operations and meaningful

relationship building with guests.

n

A second implication is that operational consistency is extremely

important in a hotel’s overall rating. Thus, focusing on avoiding

operational “kinks” can be more important than looking for the

occasional “wow” factor. Hotels that received highly variable review

scores during the twelve-month period scored much lower in the overall

ratings. Needless to say, frequent complaints about a specific area,

such as bathroom or breakfast, point to the issues that require

immediate attention.

In conclusion, we want to once again emphasize that

despite amenities creep, architectural fads, and numerous

brand permutations, the core of the hotel business re- mains

creating a positive and memorable stay by focusing on the

fundamentals of hotel operations and meaningful

relationship building with guests.

Cornell Hospitality Report • February 2017 • www.chr.cornell.edu • Vol. 17, No. 4 13

E

xhibit

10

Words most frequently mentioned in positive reviews (service subcategory at 9 or above, N=4,579) vs.

those in negative reviews (service subcategory at 4 or below, N=5,337)

Service rated 9 or above Service rated 4 or below

Word Total Occurrence Number of

Reviews that

Contain the Word

Word Total Occurrence Number of

Reviews that

Contain the Word

staff 4276 3770 hotel 6612 3076

hotel 5310 2833 room 6150 2913

great 3101 1953 location 2299 1825

room 2742 1940 staff 2171 1620

location 2233 1848 good 2068 1497

friendly 1937 1821 service 2073 1425

helpful 1693 1629 stay 1913 1411

stay 1977 1533 great 1910 1380

excellent 1849 1424 rooms 1856 1309

good 1850 1265 nice 1573 1151

nice 1653 1207 breakfast 1414 1120

rooms 1240 1091 expensive 1188 1070

clean 1116 1036 get 1328 976

service 1200 944 time 1228 930

breakfast 1049 931 night 1245 890

comfortable 961 876 food 1065 838

food 853 769 stayed 907 780

beautiful 841 696 clean 855 758

stayed 738 665 check 1082 743

perfect 715 586 day 989 741

recommend 599 579 pool 1038 701

lovely 702 559 bed 860 662

wonderful 647 559 didn’t 811 633

amazing 683 539 front 830 632

time 661 539 view 850 622

view 656 536 price 713 618

pool 640 532 place 736 597

place 615 525 bathroom 678 586

denitely 485 465 restaurant 730 581

restaurant 505 455 desk 792 579

bed 459 420 comfortable 616 572

restaurants 436 414 area 678 539

experience 473 401 experience 638 525

14 The Center for Hospitality Research • Cornell University

2017 Reports

Vol. 17 No. 3 Hotel Brand Standards:

How to Pick the Right Amenities for

Your Property, by Chekitan S. Dev,

Rebecca Hamilton, and Roland Rust

Vol. 17 No. 2 When Rules Are Made

to Be Broken: The Case of Sexual

Harassment Law, by David Sherwyn,

J.D., Nicholas F. Menillo, J.D., and Zev J.

Eigen, J.D.

Vol. 17 No. 1 The Future of Hotel

Revenue Management, by Sheryl E.

Kimes, Ph.D.

CREF Cornell Hotel Indices

Vol. 6 No. 1 Cornell Hotel Indices:

Fourth Quarter 2016: Hotels Are Getting

Costlier to Finance, by Crocker H. Liu,

Ph.D., Adam D. Nowak, Ph.D., and

Robert M. White, Jr.

2016 Reports

Vol. 16 No. 28 The Role of REIT

Preferred and Common Stock in

Diversied Portfolios, by Walter I.

Boudry, Ph.D., Jan A. deRoos, Ph.D., and

Andrey D. Ukhov, Ph.D.

Vol. 16 No. 27 Do You Look Like Me?

How Bias Aects Armative Action

in Hiring, Ozias Moore, Ph.D., Alex M.

Susskind, Ph.D., and Beth Livingston,

Ph.D.

Vol. 16 No. 26 The Eect of Rise in

Interest Rates on Hotel Capitalization

Rates, by John B. Corgel, Ph.D.

Vol. 16 No. 25 High-Tech, High

Touch: Highlights from the 2016

Entrepreneurship

Roundtable, by Mona Anita K. Olsen,

Ph.D.

Vol. 16 No. 24 Dierential Evolution: A

Tool for Global Optimization, by Andrey

D. Ukhov, Ph.D.

Vol. 16 No. 23 Short-term Trading

in Long-term Funds: Implications for

Financial Managers, by Pamela Moulton,

Ph.D.

Vol. 16 No. 22 The Inuence of

Table Top Technology in Full-service

Restaurants, by Alex M. Susskind, Ph.D.,

and Benjamin Curry, ,Ph.D.

Vol. 16 No. 21 FRESH: A Food-service

Sustainability Rating for Hospitality

Sector Events, by Sanaa I. Pirani, Ph.D.,

Hassan A. Arafat, Ph.D., and Gary M.

Thompson, Ph.D.

Vol. 16 No. 20 Instructions for the

Early Bird & Night Owl Evaluation

Tool (EBNOET) v2015, by Gary M.

Thompson, Ph.D.

Vol. 16 No. 19 Experimental Evidence

that Retaliation Claims Are Unlike Other

Employment Discrimination Claims, by

David Sherwyn, J.D., and Zev J. Eigen,

J.D.

Vol. 16 No. 18 CIHLER Roundtable:

Dealing with Shifting Labor

Employment Sands, by David Sherwyn,

J.D.

Vol. 16 No. 17 Highlights from the 2016

Sustainable and Social Entrepreneurship

Enterprises Roundtable, by Jeanne

Varney

Vol. 16 No. 16 Hotel Sustainability

Benchmarking Index 2016: Energy,

Water, and Carbon, by Eric Ricaurte

Vol. 16 No. 15 Hotel Prot Implications

from Rising Wages and Ination in the

U.S., by Jack Corgel, Ph.D.

Vol. 16 No. 14 The Business Case for

(and Against) Restaurant Tipping, by

Michael Lynn, Ph.D.

Vol. 16 No. 13 The Changing

Relationship between Supervisors and

Subordinates:

How Managing This Relationship

Evolves over Time, by Michael Sturman,

Ph.D. and Sanghee Park, Ph.D.

Vol. 16 No. 12 Environmental

Implications of Hotel Growth in China:

Integrating Sustainability with Hotel

Development,

by Gert Noordzy, Eric Ricaurte,

Georgette James, and Meng Wu

Vol. 16 No. 11 The International Hotel

Management Agreement: Origins,

Evolution, and Status, by Michael

Evano

Vol. 16 No. 10 Performance Impact of

Socially Engaging with Consumers, by

Chris Anderson, Ph.D., and Saram Han

Vol. 16 No. 9 Fitting Restaurant Service

Style to Brand Image for Greater

Customer Satisfaction, by Michael

Giebelhausen, Ph.D., Evelyn Chan, and

Nancy J. Sirianni, Ph.D.

Vol. 16 No. 8 Revenue Management

in Restaurants: Unbundling Pricing for

Reservations from the Core Service, by

Sheryl Kimes, Ph.D., and Jochen Wirtz,

Ph.D.

Vol. 16 No. 7 Instructions for the Food

Preparation Scheduling Tool v2015, by

Gary Thompson, Ph.D.

Center for Hospitality Research

Publication Index

chr.cornell.edu

Cornell Hospitality Report • February 2017 • www.chr.cornell.edu • Vol. 17, No. 4 15

Advisory Board

Cornell Hospitality Research Note

Vol. 17, No. 4 (February 2017)

© 2017 Cornell University. This report may not be

reproduced or distributed without the express permission

of the publisher.

Cornell Hospitality Report is produced for the benet

of the hospitality industry by

The Center for Hospitality Research

at Cornell University.

Christopher K. Anderson, Director

Carol Zhe, Program Manager

Jay Wrolstad, Editor

Glenn Withiam, Executive Editor

Kate Walsh, Acting Dean, School of Hotel

Administration

Center for Hospitality Research

Cornell University

School of Hotel Administration

SC Johnson College of Business

389 Statler Hall

Ithaca, NY 14853

607-254-4504

www. chr.cornell.edu

Syed Mansoor Ahmad, Vice President, Global Business

Head for Energy Management Services, Wipro EcoEnergy

Marco Benvenuti MMH ’05, Cofounder, Chief Analytics and

Product Ofcer, Duetto

Scott Berman ’84, Principal, Real Estate Business Advisory

Services, Industry Leader, Hospitality & Leisure, PwC

Erik Browning ’96, Vice President of Business Consulting,

The Rainmaker Group

Bhanu Chopra, Founder and Chief Executive Ofcer,

RateGain

Susan Devine ’85, Senior Vice President–Strategic

Development, Preferred Hotels & Resorts

Ed Evans ’74, MBA ’75, Executive Vice President & Chief

Human Resources Ofcer, Four Seasons Hotels and

Resorts

Kevin Fliess, Vice President of Product Marketing, CVENT,

Inc.

Chuck Floyd, P ’15, P ’18 Global President of Operations,

Hyatt

R.J. Friedlander, Founder and CEO, ReviewPro

Gregg Gilman ILR ’85, Partner, Co-Chair, Labor &

Employment Practices, Davis & Gilbert LLP

Dario Gonzalez, Vice President—Enterprise Architecture,

DerbySoft

Linda Hateld, Vice President, Knowledge Management,

IDeaS—SAS

Bob Highland, Head of Partnership Development,

Barclaycard US

Steve Hood, Senior Vice President of Research, STR

Sanjeev Khanna, Vice President and Head of Business Unit,

Tata Consultancy Services

Kenny Lee, Vice President of Marketing, Revinate

Josh Lesnick ’87, Executive Vice President and Chief

Marketing Ofcer, Wyndham Hotel Group

Faith Marshall, Director, Business Development, NTT DATA

David Mei ’94, Vice President, Owner and Franchise

Services, InterContinental Hotels Group

David Meltzer MMH ’96, Chief Commercial Ofcer, Sabre

Hospitality Solutions

Nabil Ramadhan, Group Chief Real Estate & Asset

Management Ofcer, Jumeirah Group

Umar Riaz, Managing Director—Hospitality, North American

Lead, Accenture

Carolyn D. Richmond ILR ’91, Partner, Hospitality Practice,

Fox Rothschild LLP

David Roberts ENG ’87, MS ENG ’88, Senior Vice President,

Consumer Insight and Revenue Strategy, Marriott

International, Inc.

Rakesh Sarna, Managing Director and CEO, Indian Hotels

Company Ltd.

Berry van Weelden, MMH ’08, Director, Reporting and

Analysis, priceline.com’s hotel group

Adam Weissenberg ’85, Global Sector Leader Travel,

Hospitality, and Leisure, Deloitte

Rick Werber ’83, Senior Vice President, Engineering and

Sustainability, Development, Design, and Construction, Host

Hotels & Resorts, Inc.

Dexter Wood, Jr. ’87, Senior Vice President, Global Head—

Business and Investment Analysis, Hilton Worldwide

Jon S. Wright, President and Chief Executive Ofcer, Access

Point Financial